|

Chapter

Eighteen Gobernador

Juan Bautista de Anza y

Bezerra Nieto

As my progenitors were from España and thus Españoles,

I’m duty bound to present them in a more truthful, honest, and thoughtful

light. I will not provide as non-Spanish writers and commentators’ subtexts

do, offering narratives with an underlying and often distinct theme in their

writing which is decidedly anti-Spanish. For them pobladores

are never just settlers, they must always be colonists. Spanish soldados

are not soldiers, they’re always conquistadores.

So rather than being resourceful, brave, and ingenious people Españoles are depicted as greedy, brutal, ugly, murderous

caricatures. This will not be the case in this chapter. In this chapter, I’m attempting to expand the

vision for most readers regarding how 18th-Century C.E. España and Españoles are

viewed. Typically non-Spanish writers and commentators provide cardboard cut-out

type characters of Spanish explorers, military men, civilians, and governmental

administrators. The person this chapter was written about,

Gobernador Juan Bautista de Anza y Bezerra Nieto (July

7, 1736 C.E.-December 19, 1788 C.E.), was a man of flesh and blood not a cardboard cut-out character.

He lived, breathed, loved, felt, cared, explored, fought, built, and died. Anza y Bezerra Nieto didn’t do any of these things in a vacuum.

His life and accomplishments impacted people he loved and cared for, such as

those progenitors and distant relatives of mine, those de Ribera soldados, who fought with him against the Comanche

and knew him personally. Anza was not just a soldier, that life, his life, also affected his

enemies. In the case of Juan Bautista de Anza, or Anza,

his life’s work was far more than just a series of battles. There were also

the journeys of exploration which took him far and wide. He was a complex human

being led by strength of character. Juan

was true to his calling as a soldado,

but he was also a diplomat and highly capable administrator. He understood the

arts of accommodation and governance when it came to the lives of his people and

the Natives who shared his culture, religion, and values. Anza

was first and foremost a just administrator. Beyond this, as a leader, Anza was part of a more complex Spanish cultural, economic,

military, and religious infrastructure. España’s

Corona Española had by the time of

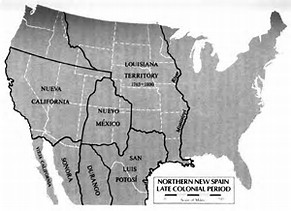

his birth and long military career expanded its Nuevo Mundo possessions world-wide. Unfortunately, España

was by then, a power in decline. Yet her settlements in Nueva

España continued to look for ways to expand and improve their common

interests through exploration and commerce. However, their military power

remained an important part of that equation for Nueva

España’s success.

To better understand this unique personality, one

must place the man in the context of his environment and his times. His world

included a political gravity centered half the world away in España

which dictated policy and action throughout the Nuevo

Mundo. Nueva España was only an extension of that political hub at Madrid. Both distance and time played major parts in critical policy

and military decision-making and the ultimate outcomes resulting from commands

coming from the Corona Española. A third important element for decision-making and

policy implementation was that of governance and those who held power in those

far-away places in the Nuevo Mundo.

Those who mattered in this scenario were the Peninsulares or those Españoles

born on the Ibero Peninsula. The Criollos

or Españoles born in América,

were second tier inhabitants of the Nuevo

Mundo with little social standing, power, or authority. They stood only

above the Mestízos or persons of

mixed racial ancestry, especially of mixed European and Native American

ancestry. The last tier of the social ladder was held by the Natives. Therefore, men such as Anza, Criollos, were

suspect and considered inferiors. Only through great feats of military courage

and success, exploration and the finding of valuable resources and other assets,

and highly-regarded administrative skills did a Criollo reach coveted positions of power and material success. Anza

was such a man. The final area of competence for a Criollo

who would be a leader in Nueva España

was the ongoing relations with the Church and its hierarchy. In the Nuevo

Mundo that was no easy task. The military and the Church had been at odds

since the beginning of settlement over the treatment of Natives. The name Anza

is Vasco. Vascos were granted nobility in the 14th-Century C.E. by the Corona

Española of Castilla (España). The

use of the "de" infers that his family line was of the nobility of el

Imperio Español. Juan Bautista de Anza

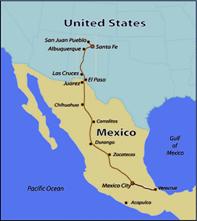

was the son of presidial Capitán, de Anza

(Anssa), and María Rosa Bezerra Nieto of Frontéras,

Sonora, Méjico. She was of Criollo

birth, an Américano-born child of

Spanish parents. Born at the Presidio

of Janos, the date is estimated at

between 1695 C.E. and 1700 C.E. The Presidio

of Janos was under continuous attack

and raided by marauding Apaches and

other belligerent Native tribes. Her parents were António Bezerra Nieto, a presidial capitán, and Gregoria

Catalina Gómez de Silva of Janos,

Chihuahua, Méjico. Little is known of

her childhood beyond the fact that she lived at one of the northernmost frontéra

outposts of Nueva España. His

grandfather was António de Anza a

pharmacist and his grandmother was Lucía

de Sassoeta of Hernani Guipuzcoa, España.

For the purpose of clarification his surname was

"Anza." An erroneous

20th-Century C.E. tradition applies the 14th-Century C.E. designation of

nobility granted to the Anza family

“de” and to refer to him

as "de Anza." Never, in Anza's

day did he or any of his contemporaries refer to him "de

Anza" when referring to him by surname. Over one hundred and fifty of

his signatures are available for study. In all, he signed only his surname,

deleting Juan Bautista, each time

signing only "Anza." With

that said, I will use only Anza

without the “de”

in the remainder of this chapter. The archives in Old Méjico and Sevilla, España

microfilm documentation and hard copy information available on Anza.

There is also a great deal of information about him in secondary literature.

However, it would appear that much is erroneous. In the Bancroft Library in

Berkeley, California and Documentary

Relations of the Southwest in Tucson, Arizona are kept

other valuable sources of information regarding Anza. In an effort to expand its Nueva España settlements, attempts had been made by España

since the 17th-Century C.E. to find a passable land route through Baja

California. The region proved to be treacherous and difficult and none had

been discovered. During the period, only sea routes provided a solution. In this chapter, the reader will notice the

absence of the term “colonies” which has been used in the past by

anti-Spanish, non-Spanish, Anglo-Americans, Northern European, and other writers

and commentators for a subliminal negative effect upon the Spanish entrants to

the Nuevo Mundo and their

accomplishments. The more appropriate term “settlement” is use instead.

By the 1700s C.E., a string of presidios

and misiónes stretched across the landscape of the Spanish Américas,

as was the case in Nueva España.

These were a connective geographic network of Spanish governmental, military

defensive sites, communications capabilities, cultural, economic, and religious

infrastructure. In time, what would eventually emerge were the

concept, exploration, and settlement which were to extend España's reach from her Nueva

España northern most settlements into Alta

California. Juan Bautista Anza's

expeditions were driven by this combination of Nueva España expansion, internal Spanish governance, and the

Church’s misiónero commitment.

By 1737 C.E., Anza’s

father Juan Bautista de Anza I, Comandante

of the post at presidio of Frontéras since 1719 C.E., was preparing to make an attempt to

locate a route to California. Unfortunately, Juan's father was killed in combat in 1739 C.E. by Apaches

before the senior Anza could make the

journey. Little is known of Juan’s

childhood except that when he was about three years of age, Juan's

father was killed by Apaches. Following family tradition at age sixteen, Juan

joined Spanish miquelets in December 1, 1752 C.E., at San Ignacio, Sonora, Méjico at the Frontéras. Two years later, in 1754 C.E. at eighteen, Anza

became a cadete in the presidial cavalry at Frontéras, Sonora, and Méjico.

This he did under the supervision and training of his brother-in-law, Gabriel

de Vildósola. At nineteen, on July 1, 1755 C.E., Anza

was promoted to Teniente at Frontéras, and, after participated in campaigns against the Indians

in Sonora. By age twenty, Anza advanced to the rank of cavalry teniente at Frontéras in

1756 C.E. Three years later, at age twenty-three, Juan

made the rank of capitán of the Tubaca (Tubac) Sonora, Méjico

(Present-day Arizona) Presidio

in December 1759 C.E. By

1760 C.E., at age thirty, Anza was

promoted to the rank of Capitán and Comandante

of the presidio at Tubac. While

there, he perfected his skills as a soldado

and comandante en Jefe when fighting

the fierce Apaches in the north, at

today’s Arizona and Seris Indians in the south near present-day Hermosillo, Sonora. Anza

led five expeditions against the rebellious Seris.

Anza also became well known for his

attention to professional and appropriate soldiering. As a result, by the age of

thirty Juan's military career was

advancing. On June 24, 1761 C.E., at almost age thirty-one, Juan

married Ana María Pérez Serrano of Arizpe,

Sonora. No children were born to the two. By the mid-1760s C.E., España faced a greater challenge to its hegemony on the Pacific

Coast from rival European powers. These nations were anxious to expand their own

empires at the expense of España’s.

Therefore, España's rivals

systematically tested the resilience and effectiveness of imperial governance

and military capabilities engaging privateers for the tasks. They searched for

areas of weakness which could be exploited. At various times, both Britain and

France progressively antagonized Spanish commerce on the high seas attacking

shipping when an opportunity presented itself. These pirates under orders from

Paris and London harassed and took slow-sailing Spanish cargo ships. This

systematic pirating was followed by the launching of voyages of discovery in the

Pacific. The Russians had also become a problem. They had

settled Alaska and were exploring the West Coast for trading posts within

striking distance of the rich Spanish mines. The Russians had also made forays

along the North American Pacific Coast extending as far south as Oregon. These

were searching for Nuevo Mundo sources

of otter and seal pelts. This Russian exploration into California

alarmed the Spanish Virrey in Méjico

City knowing that the rivalry would continue as far south as Spanish California. The settlement of Las Californias would

begin with the el Imperio Español's

discovery of Nueva España, today’s Méjico

and some areas of the United States, the modern-day American states of Tejas,

Arizona, Nuevo Méjico, California, and other lands which made up Nueva

España. California would be one of the last of these Spanish provinces to be

settled. When discussing the early Las Californias, the misiónes,

presidios, pueblos, estancias, and ranchos

are invariably remembered. Almost everyone has visited or read about the old

town or pueblo of San Diego, and the pueblo

of Los Ángeles, the misiónes

at Santa Bárbara and Monterey,

and the presidio at San

Francisco,. However, one important

part of the pastoral era of California history is not as easily remembered, it is the Spanish ranchos

and estancias. Unfortunately, there is very little visible evidence of

these large ranchos and

estancias with their adobe houses.

One cannot stand in many of the downtowns’ of California

and physically touch or see the old ranchos

or the estancias. As a result, these are almost forgotten as part of California's

past. Fortunately, the misiónes,

presidios, and pueblos have not

been forgotten. One of these pueblos

is San Francisco with its misión

and presidio. The first Alta

California Spanish settlement with its

misión and presidio was established at San

Diego. From this first settlement, the Spanish Gobierno founded 4 presidios,

4 pueblos, and 21 Catholic misiónes.

In addition, the Gobierno granted vast

amounts of rancho and estancia lands to pobladores

and soldados. Throughout the Spanish Américas, including Nueva

España (Today’s Méjico and the

U.S.) and Latino América, a system of

military outposts was created for the protection of Spanish Ciudádanos.

Called presidios, they were established to maintain order and enforce

Spanish governance. During the period, España

had also invited various orders of the Catholic Church to establish misiónes,

believing that Spanish subjects should also be Christians.

The soldados

of El Imperio Español and pobladores

in Nueva España would over

time become a mixture of European, Native American, and African heritage. Each

brought with them their own traditions and culture, melding into one in the

Spanish Américas. By 1767 C.E., at the age of thirty-seven,

interestingly Anza was one of the

Spanish officers charged with the gathering and removal of Jesuit misióneros from Sonora by

José de Gálvez, the Inspector General

of Méjico. España's

internal situation had been experiencing complicated and difficult matters

between Church and state authorities. Many believed that the Society of Jesús

(Jesuits) had acquired too much influence, power, and wealth contributing to

dysfunction in Spanish affairs. This was supposedly accomplished through

political intrigues by the frayles. To

counter this perceived overreach of power by the Jesuits, King Cárlos It would appear that Anza’s competence in these matters of Church and state was

appreciated by de Gálvez,

bringing him close to the famous, powerful, political, and appreciative de

Gálvez family. One of these new Franciscans to enter the vacuum

was Fray Juan Crespí. He entered the Baja

California Peninsula in 1767 C.E. and was placed in charge of the Misión

La Purísima Concepción de Cadegomó. Misión La Purísima was founded west of Loreto

in Baja California Sur, by the Jesuit

misiónero Nicolás Tamaral in 1720

C.E. By 1735 C.E., it was moved to a new location at the Cochimí ranchería

known as Cadegomó, meaning "arroyo

of the carrizos," about 30 kilometers south of the original site. By 1768 C.E., the Virrey of Nueva España, António

María Bucareli y Ursúa was growing more and more concerned about the

probability of Russian encroachment and eventual incursion on what was

acknowledged Spanish territory. He ordered Capitán

Juan Bautista Anza to recruit soldados

and pobladores in Sonora, Nueva España (now Méjico),

prepare an expedition, and establish a misión

and presidio in the port of San

Francisco. A story is recounted about the naming of San

Francisco by California's first historian and the first Franciscan pastor of Misión

Dolores, Fray Francisco Palóu. In 1768 C.E., José de Gálvez informed Junípero

Serra of the names to be given to the Misiónes

to be established in Alta California.

Serra remonstrated saying, "Is there then to be no Misión

for Our Father San Francisco?"

de Gálvez jested, "If San

Francisco wants a misión, let him

cause his port to be discovered, and it will be placed there!" As fate

would have it, San Francisco would

lead España to this future port.

Seven years later, Juan Bautista Anza

would march north from Pueblo San Diego

with a settlement party to establish a Spanish presidio

and misión named San Francisco. From 1769 C.E. to 1772 C.E., in a separate but

coordinated effort, the soldado Gaspar

de Portolá i Rovira and

the Franciscan frayles made their way

northward up to Alta California

along the Pacific Coast from Baja California. The Land Expedition would travel north to Alta

California (Future state of California) through

the present-day coastal counties of San

Diego, Orange, Los Ángeles, Ventura, Santa

Bárbara, San Luis Obispo, Monterey, Santa Cruz, San Mateo,

and San Francisco. They and the

dedicated soldados of the Land

Expedition founded a series of coastline outposts. However, these expeditions

led by de Portolá in 1769 C.E.

created only small settlements in Alta

California and once there, the Españoles

would have to fight to exist due to a lack of resources. This Español,

de Portolá was born on January 1, 1716 C.E. in Os de Balaguer, in Cataluña, España, of Catalán

nobility. Don Gaspar

served as a soldado in the Spanish

army in Italy and Portugal. He was

commissioned alférez in

1734 C.E., and teniente in

1743 C.E. The Franciscan Fray, Juan

Crespí joined the Land

Expedition led by Gaspar de

Portolá and Junípero Serra

in 1769 C.E. As Crespí was the only

Franciscan fray to make the entire

journey by land, he became the first official diarist for the misiónes.

He was one of three diarists to document the first exploration by Europeans of

interior areas of Alta California.

Fray Crespí

traveled in the vanguard of the Expedition led by Capitán Fernando

Rivera (Ribera) y Moncada up to San Diego

in Alta California. There a presidio

and misión were established. Fray Crespí would eventually continue north with de Portolá

and Capitán Rivera to identify the port of Monterey. After reaching Monterey

in October 1769 C.E., Fray

Crespí continued with a

de Portolá scouting party and explored as far north as present-day San Francisco Bay. He

became one of the first Europeans to see the Bay. By 1769 C.E., the establishment of another presidio

north of the Monterey area was not in

the original plans of the Spanish Monarch, Cárlos

III. Perhaps this is due to España’s

having no knowledge of the large body of water to the north. However, Vizcaíno

era maps did refer to a river at the location of the Golden Gate but it was not

explored and the location was passed by. This would all change on July 14, 1769 C.E., when San

Francisco Bay was rediscovered by the Land Expedition from San

Diego. The first westerners to see the bay of San

Francisco would be members of the 1769 C.E. Gaspár de Portolá Expedition. After establishing a limited control

over San Diego, de Portolá took a

small party north in search of Monterey.

An advance de

Portolá Expedition party under Sargento

José Francisco Ortega, a Criollo

born in Guanajuato in central Méjico,

reported that they had seen a "brazon

del mar" - an arm of the sea and noted that sighting. They had sighted

what would eventually would be known as the Golden Gate and the San Francisco

Bay, on November 1, 1769 C.E. This made the Europeans aware of the existence of

the immense bay and its beautiful passage through the coastal mountains. Ortega would, was to serve at the guarniciónes of San Diego,

Santa Bárbara, and Monterey

during his career. By the 1770s C.E., the Españoles had been in the Nuevo

Mundo Américas for over 200

years. Their Imperio Español included

the present-day western United States, Florida,

and the Filipinas. Yet, they had not

secured the Pacific Coast from English and Russian incursion. In 1770 C.E., the Spanish soldado, Don Pere Fages i Beleta or Don Pedro Fages (1734 C.E.-1794 C.E.),

assumed the responsibility for establishing a land route in Alta

California to the north. Fages was

born in Guissona, Lerida province, Cataluña, España. In 1762 C.E. he entered the light infantry in Catalonia

and joined España’s invasion of Portugal

during the Seven Years' War. In May of 1767 C.E., Fages was commissioned as a teniente

in the newly formed Free Company of Volunteers of Cataluña. He set sail from Cádiz along

with a company of light infantry, voyaging to Nueva

España (Méjico). He and his men

were to serve under Domíngo Elizondo in Sonora. Capitán Gaspar de Portolá

led an expedition to establish a Presidio

at Monterey. He was joined by

Franciscan Fray Junípero Serra. On June 3, 1770 C.E. a mass was held under an oak tree at the

same location where Vizcaíno had held

mass 168 years earlier. Sebastián Vizcaíno (1548

C.E.-1624) was born in 1548 C.E., in Extremadura, Crown of Castilla (España).

Coming to Nueva España in 1583 C.E.,

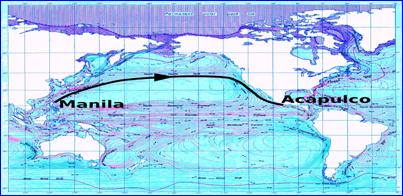

he sailed as a merchant on a Galeón

de Manila to the Filipinas in 1586

C.E.-1589 C.E. The disputed concession for pearl fishing on the western

shores of the Gulf of California was

transferred to Vizcaíno in 1593 C.E. Sebastián

succeeded in sailing with three ships to La

Paz, Baja California Sur in 1596 C.E. He then gave this site which had

been known to Hernándo Cortés as

Santa Cruz, its modern name,

La Paz. Soon thereafter, he and attempted to establish a settlement.

Unfortunately, difficulties with declining morale of the pobladores

and soldados, resupply of needed

resources, and a fire soon forced the abandonment of the new settlement. By 1601 C.E., the Virrey, the Conde de

Monterrey at Méjico City,

appointed Vizcaíno general-in-charge

of a second expedition. This was to locate safe harbors in Alta California for Galeónes

de Manila to use on their return voyage to Acapulco from Manila.

Sebastián was also given the

responsibility to map the California coastline

that Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo had

first reconnoitered 60 years earlier in detail. He departed Acapulco

on his flagship, the San Diego,

on May 5, 1602 C.E. With him were two other ships the San

Tomás and the Tres Reyes. On November 10, 1602 C.E., Vizcaíno entered and named San

Diego Bay. Sailing up the Pacific Coast, Vizcaíno named many places such as the Santa Bárbara Channel Islands, Point Conception, the Santa

Lucía Mountains, Point Lobos, Carmel

River and Monterey Bay. In

taking these actions, he changed the names given these by Cabrillo

in 1542 C.E. As a result of Vizcaíno's voyage, there was a flurry of enthusiasm for

establishing a Spanish settlement at Monterey.

Unfortunately for him, this was ultimately deferred for another 168 years after

the Conde de Monterrey left to become Virrey of Perú. A

colonizing expedition had been authorized in 1606 C.E. It was to proceed in 1607

C.E. However, it was delayed and later cancelled in 1608 C.E. Finally, at the same oaks where Franciscan Fray

Junípero Serra said mass, Monterey

was founded. The Royal Presidio and Misión,

San Cárlos de Borromeo de

Monterey, were established as Monterey’s

first buildings. Don Pere Fages i Beleta,

now in Nueva España rode to the Llano de

Los Robles or Plain of the Oaks (Later known as Santa Clara Valley) with a handful of Lanceros and some muleteers (mule drivers). The arrival of the Españoles

to the Llano de Los Robles resulted in these Spanish explorers describing

the Llano de Los Robles as a broad

grassy plain. It was covered with oaks and well-watered with marshy creeks and

rivers. Their courses could be traced from a distance by the trees growing along

their banks. The astute explorers

commented on the abundance of good agricultural land. They also took notice of

the number of Indian ranchería.

All agreed that Llano de Los Robles

was an excellent place for a misión.

There, the church of Misión Santa Clara

de Asís would be founded in 1777 C.E. It was to be the first outpost of

Spanish civilization in the Santa Clara

Valley. From there they went east, encamping near the

present-day city of Alameda. By

November 28, 1770 C.E. the men viewed a large "bocana" or estuary mouth. Not being able to cross the Punta

de los Reyes, Fages halted and then made his way back to Monterey. By 1771 C.E., expeditions led by Gaspar

de Portolá established more small settlements in Alta

California. These would create a greater need for support and protection

from the Corona Española. In 1772 C.E., the landscape of Baja

California was largely a desert. Its sand dunes eventually came to an abrupt

end at steep mountains. However, España’s

increasing awareness of the need to consolidate its hold on the Pacific Coast

forced the issue of overcoming the desert and finding a route through it for

settlement of Alta California. This situation prompted Anza, among others, to pursue opening such a land route. That same

year, the ever eager Anza requested

permission from the Virrey of Nueva

España to discover a route to Alta

California. March of 1772 C.E. saw Don Fages once again returning north with six soldados, a muleteer, a Native American servant and the Fray,

Juan Crespí (March 1, 1721 C.E.-January 1, 1782 C.E.). He was a Franciscan misiónero and was to become an explorer of Las

Californias. A native of Mallorca

in Cataluña, Crespí entered the

Franciscan order at the age of seventeen. He came to Nueva

España in 1749 C.E., and accompanied explorers Francisco Palóu and Junípero

Serra. Fray Juan Crespí accompanied

Capitán Pedro Fages in order to

gain a clearer understanding of the large body of water to the north. From the

east bay they saw the Farallónes (Farallon

Islands) and three islets within the bay that someday would be known as Alcatraz,

Angél Island, and Yerba Buena.

Armed with this added intelligence, Don

Fages' party concluded its journey with a report and chart that prompted

additional interest in the region. On that exploration of areas to the east of San

Francisco Bay, the Fages

Expedition members were the first Europeans to see the Sacramento

River and the San Joaquín

Valley. Having read these reports, Padre Junípero Serra began to lobby the Virrey of Nueva España

for two more misiónes in the vicinity of what came to be called the Port of San

Francisco, one in the Santa Clara Valley

and one at the opening to the bay. Don Pedro Fages felt

that he did not have enough soldados

to support another misiónero program.

However, Virrey António Bucarelli y Ursúa

championed Serra's cause,

relieving Don Fages and replacing him

with Capitán Fernando Xavier de Rivera y Moncada (c. 1725 C.E.-July 18, 1781 C.E.)

as military comandante of Alta

California. Don Fages was transferred to the Apache wars in Arizona. Rivera y Moncada,

a Criollo, was born near Compostela, Nueva

España (Mexico). His father, Don

Cristóbal de Rivera, was locally prominent and a local office holder. Rivera

was born of Don Cristóbal's second

wife, Joséfa Ramón de Moncada. He

entered military service in 1742 C.E., serving in Loreto,

Baja California, at a time when that peninsula was almost totally under the

control of Jesuit misióneros. In 1751

C.E., Rivera was elevated over several

older and higher ranking soldados to

the command of that presidio. He

participated in the important reconnaissance of the northern peninsula together

with the Jesuit misiónero-explorers Ferdinand

Konščak and Wenceslaus Linck. In 1755 C.E., Rivera

would marry Doña María Teresa Dávalos;

a marriage probably arranged by their parents. The couple had four children;

three boys and a girl. His tenure as military comandante of Baja California

was generally successful. He was highly thought of by the Jesuits, though he was

also embroiled in conflicts with local Ganaderos,

and miners who were in conflict with the Jesuits. By 1773 C.E., there would be two presidios

and five misiónes in Alta California.

At that time, the total population of Españoles

was about seventy frayles and soldados.

They had established five misiónes: ·

San

Diego de Alcalá in 1769 C.E. ·

San Cárlos

Borromeo del Carmelo in 1770 C.E. ·

San António

de Padúa in 1771 C.E. ·

San

Gabriel Arcángel in 1771 C.E. ·

San Luís

Obispo de Tolosa in 1772 C.E. Two presidios

were established at San Diego and Monterey The viability of España's Alta California outposts immediately came into question.

Problems obtaining badly needed supplies jeopardized expansion into the region

and maintaining outposts in the region. The sixty-one soldados and eleven Franciscan frayles

that were assigned to various settlements were almost completely dependent upon

supplies from Nueva España’s

capital at Méjico City for their

survival. The Españoles encountered

continual difficulties obtaining these supplies which led to starvation

conditions. To

ensure their possession and the protection of Alta

California, the Españoles needed

an overland route in Nueva España

originating in Sonora. Resupplying the settlements by way of by of Méjico

City via the sea had been extremely difficult. This made further settlement and

supply of Alta California even more

challenging. The small Spanish ships that made the arduous sea voyage were from San

Blas, Nueva España (Méjico). San Blas is a port located about 99 miles north of Puerto

Vallarta, and 40 miles west of the state capital Tepic. These

ships were unable to carry cattle or many people. In addition, the prevailing

Pacific winds and currents along the California

Coast made trips hazardous. Each trip north from San Blas in Baja California

to Monterey took five times as long as

did the returning trip south. To make matters worse, ships were frequently lost.

Some were blown out to sea or destroyed on the rocky coastline. Despite these

obstacles, the sea route proved more advantageous than the treacherous and

difficult land route through Baja

California.

It was the Jesuit padres who engineered the El

Camino Real portion of the road in

Baja California. The Spanish soldados

built the first sections on the peninsula. Later the natives did more of the

work. The network of roads radiated outward from the first mission at Loreto,

the Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto

Conchó or Our Lady of Loreto Misión.

Loreto is a coastal villa

on the Sea of Cortés. There the misión

was founded. It is the first and oldest misión

built in either Baja or Alta California. The early

misión was the center for further

exploration into the deserts and mountains of Baja. It also aided in the expansion of the Catholic misión

system.

The Jesuits had originally established Misión

de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó in 1697 C.E in Loreto.

Soon it became obvious that the Loreto

site had too little water to be suitable for agriculture and, thus, could not

become self-sustaining. The Jesuits were told by Cochimí

visitors to Loreto of potential

agricultural land across the nearby Sierra

de la Giganta. In May 1699 C.E., Francisco María Piccolo, along with a dozen Cochimí guides and ten Spanish soldados,

crossed the mountains on horseback and entered the valley the Indians called Biaundó,

about 12 miles inland from the Gulf of California.

The other part of the Misión's name, Viggé,

was the Cochimí word for mountain. The inhabitants of a Cochimí rancheria at

the site were friendly and Piccolo

baptized 30 of their children. In October 1699 C.E., Piccolo returned with a contingent of soldados and Indian converts and began to construct the Misión.

Piccolo dedicated the Misión

on December 3, 1699 C.E., and San

Francisco Javier (also Xavier)

became the second most enduring misión

established in Baja California. The Misión

was abandoned in 1701 C.E. because of a threatened Indian revolt, but

reestablished by Juan de Ugarte in

1702 C.E. However, efforts to grow crops proved unsuccessful due to lack of

water for irrigation and in 1710 C.E. the Misión

was moved a few kilometers south to its present location which had a dependable

source of water from a spring. The energetic Ugarte constructed dams, aqueducts, and stone buildings. Between

1744 C.E. and 1758 C.E., Miguel del

Barco took the responsibility for building what became known as

"the jewel of the Baja California

misión churches."

Later, El

Camino or more properly El Camino Real

de Tierra Adentro (The Royal Road) of the Interior Land would be extended

from Tucson to San Diego.

In 1773 C.E., at age thirty-seven, Anza

received permission to lead the overland exploratory expedition to Alta

California for locating and mapping an overland supply route from António

María Bucareli y Ursúa, the region's virrey.

This initial launch to Alta California

found its feasibility in Anza's belief

that such a route was possible. Anza,

Comendador of the presidio at Tubac, Nueva España (Now Arizona),

was friendly with the local Yuma

Indians. His conversations with the Yuma

convinced him that a supply route was feasible. On September 17, By 1773 C.E., Anza

was ordered to explore for a route from Tubac,

Arizona to Alta California. In 1774 C.E., Fray

Juan Crespí was Capellán of the

expedition to the North Pacific conducted by Juan José Pérez Hernández. His diaries provided valuable

records of these expeditions. One chapel he built, at the Misión

San Francisco del Valle de Tilaco in Landa,

located in today’s Jalpan de Serra

region of Méjico. It is reported to

still be standing. Anza's Spanish military contingent set out from Tubac,

Arizona on The Expedition headed north and reached the Yuma

village at the junction of the Gila

and Colorado rivers without much difficulty. With the help of the Yuma

Indians, the Españoles crossed the Colorado

River, and proceeded southward in an attempt to circumnavigate the sea of sand

dunes. During the effort, Anza's party

became lost. After ten days of traveling in the desert, they found their way

back to the Colorado River. The Españoles

were soon reunited with the Yuma

Indians. Determined to continue, Anza

followed Tarabal's suggestion, which offered a more northerly route through

the San Gabriel Mountains. By March 22, 1774 C.E., Anza crossed the Colorado

River, and arrived on the Pacific Coast at San

Gabriel near present-day Los Ángeles.

Within days, they camped along the San

Jacinto River. The party had finally reached Misión San Gabriel. Although the weather was relatively cool, the Anza

Expedition had traversed the most arid region of North America. Men and

livestock relied on the infrequent oases and natural cisterns, and after a month

of trial and error they opened a trail from the Colorado

River across the barren Imperial and Mexicali valleys to the San

Jacinto Mountains. After a needed rest, Anza reached the presidio

of Monterey sometime between April 18,

1774 C.E. and May 1, 1774 C.E. They had finally reached Monterey,

California. This difficult three month expedition and journey was plagued

with frequent bouts with starvation. Fortunately, Juan

Bautista had accomplished his goal of discovering the much needed overland

supply route. This effort would expand Spanish settlement in California. Anza had

successfully found an overland route and traveled to the newly established Presidio

of Monterey, California. His mission was successful. It would ensure Juan's

advancement and appointment by the King of España

to Teniente de Coronel. Juan’s

expedition of discovery has also secured him a place in history. The question

remained, whether it could be used for large-scale expeditions. After staying only three days in Monterey,

the confident explorer, Anza, would

retrace his route. By May 5, 1774 C.E., he was again at San

Gabriel. By May 28, 1774 C.E., he completed the return trek

to Tubac. Unbelievably, his

expeditionary force had returned back in Tubac,

Arizona by the end of May. Anza

upon his return was then promoted to teniente

de coronel. Later, Anza

reported to Bucareli in Méjico

City and delivered his diaries. In August, 1774 C.E.,

Naval Officer Manuel de Ayala y

Aranza arrived in Vera Cruz and

proceeded to Méjico City to

receive orders from the Virrey, Don António María de Bucareli y Ursúa regarding Alta California. Also, in 1774 C.E., an exploration expedition led

by Capitán Fernando Rivera y Moncada

began explorations for a suitable site for the Misión of San Francisco.

Charged with another survey of the "Port and River of San Francisco," Rivera

commanded 16 Lanceros, a muleteer, two

servants and one fray, another native

of Mallorca, Fray

Francisco Palóu. The 21 riders left Monterey

on November 23, 1774 C.E. By November 24, 1774 C.E., Capitán Juan Agustín Bautista Anza

was ordered by Virrey Bucareli to

return to California from

Tubac via

his earlier established overland route.

Virrey Bucareli had turned to the experienced Capitán

Juan Agustín Bautista Anza of the

Tubac Presidio, in

present-day Arizona, to found the San

Francisco presidio and provide the Christianized Méjicano

and Native American pobladores for the

misiónes. The new overland Settlement Expedition was to

arrive, settle, and exercise control of the region. At this point in time, the Españoles

had no ships stationed in the area with which to go further north and provide

any meaningful control across the Bay. Anza

would eventually leave with a group of pobladores

and twenty-eight soldados to found a

new misión and presidio on the bay of San

Francisco. Some 136 pobladores

were enlisted, and, with two Franciscans, two officers, ten soldados,

and thirty-one muleteers. By December 4, 1774 C.E. Rivera’s Exploration Expedition halted at "a long lake ending

down at the shore" (now Lake Merced in the southwestern part of San

Francisco). Rivera continued on with Palóu

and four troopers until they reached either what now is called Land's End or

perhaps present-day Point Lobos, where

they set up a cross. Presents were made to Ssalson Ohlone people of beads and

Spanish food, including wheat and frijoles.

Palóu records in his diary that the

Indians were much taken with the products of European culture and Palóu

promised that he would return and help the First Peoples to plant seeds and

gather them in great abundance. Palóu

believed that the Ohlone were pleased, understood him and would help build

houses when he returned to establish a misión. Rivera’s Exploration Expedition headed home making their

way to Monterey by December 13, 1774

C.E. The result of the Rivera Expedition was a plan with a program for second Anza

Expedition to settle the area south of the Golden Gate with a presidio

and a misión. Here, at the

northernmost area of the Spanish possessions in California, Anza’s

second expedition, an overland Settlement Expedition, was to facilitate the

second phase of these plans. The second Anza

Settlement Expedition was to be launched immediately, reflecting a settlement

mandate. In this mission he was joined again by Gracés and Tarabal. His

second-in-command was to be José Joaquín

Moraga, an eighteen-year military veteran. The strength and number of Anza's Settlement Expedition has been subject of debate. Anza's

diary indicates 240. However, recent analysis of his letters suggests it might

have been closer to three hundred. Recruits were also gathered at the Presidio

of San Miguel de Horcasitas, Sonora's

provincial capital. There, Anza had

chosen as his Teniente, José Joaquín

Moraga. Fray Pedro Font, a Franciscan

misiónero, was picked as expedition Capellán

for his ability to read latitudes.

Bucareli

sent de Ayala y Aranza to San

Blas where he took command of the schooner Sonora,

part of a squadron under the general command of Don Bruno

de Heceta, in the frigate Santiago. The squadron sailed

from San Blas early in 1775

C.E. However, when they were lying outside San

Blas about to set out, the commander of the packet-boat San Cárlos,

Don Miguel Manrique, was taken ill. Ayala y Aranza was ordered to take command of this larger vessel,

sailed back to San Blas to return the

unfortunate Manrique. He and rejoined

the squadron after a few days' sailing. Ayala

y Aranza was designated to pass through the strait and explore what lay

within, while the Santiago and Sonora continued

northwards.

As Juan

prepared for his next accomplishment, he continued recruiting through April and

May. His efforts also took him to find recruits in the villa of El Fuerte in the

Province of Sinaloa and Alamos

in Sonora. Eventually accompanying the main force would be

twenty-nine women (wives of the soldados),

four volunteer families, 128 children, twenty muleteers, three vaqueros,

three servants, and three Indian interpreters. The expedition would also bring

695 horses and mules, and 355 cattle for the purpose of food and future

livestock expansion in the northern Nueva

España region. Additionally, Anza

would recruit some 170 pobladores,

most of whom had been living on the edge of poverty. Anza remained the summer in Horcasitas, the capital of Sonora.

There he spent time training his new recruits for the difficulty that lay ahead.

The crossing of Apache country would

be no easy matter. In the early 1770s

C.E., the Spanish royal authorities had also ordered a naval exploration

of the north coast of California,

"to ascertain if there were any Russian settlements on the Coast

of California, and to examine the Port

of San Francisco." By this time, Don Fernando

Rivera y Moncada had already marked the point for a misión

in what is now San Francisco.

Also, a Land Expedition to establish Spanish rule over the area, under Juan

Bautista Anza would be sent northwards. Juan

Manuel de Ayala y Aranza,

then a teniente was one of

those assigned to the naval expedition. In 1775 C.E., 30-year-old de

Ayala y Aranza (December 28, 1745 C.E.-December 30, 1797 C.E.) was

one of those preparing the way for Spanish settlement in northern California.

De Ayala y Aranza was a Spanish naval officer,

born in Osuna, Andalucía.

He entered the Spanish navy on the September 19, 1760 C.E., and rose to achieve

the rank of Capitán by 1782 C.E.

He would retire on full pay due to his achievements in California on March 14, 1785 C.E. As the skipper of the packet-boat San Cárlos,

de Ayala y Aranza sailed from San Blas

with supplies for the proposed settlement. His other duties included the

charting of the bay and its shoreline, and ascertaining whether a navigable

passage existed to the inland waterway from the sea. Finally, Ayala

sought to learn whether a port could be established there. The packet-boat

San Cárlos took on supplies at Monterey, leaving there on July 26, 1775 C.E. and then proceeding northwards. On August 4, 1775 C.E. the San Cárlos arrived just outside present-day Golden Gate. Ayala

y Aranza passed through the Golden Gate on August 5, 1775 C.E.,

with some difficulty and great caution because of the tides. He tried a number

of anchorages, finding that off Ángel

Island most satisfactory, but failed to make contact, as he had hoped, with

Anza's party. That morning, Ayala

sent his First Piloto, José de Cañizares, into the harbor with a longboat. That evening

he followed, anchoring somewhere near what became North Beach. Ayala

y Aranza then placed a wooden cross where he landed the first night. This

was the first European ship to enter this great bay. On August 12, 1775 C.E., de Ayala y Aranza gave the

name Isla de Alcatraces (Alcatraz),

"island of the pelicans," and what is now Yerba

Buena Island, "on account of the abundance of those birds that were on

it." For some next 44 days, de Ayala y Aranza and Cañizares

completed a thorough reconnaissance before the San Cárlos headed

back to Monterey on September 18, 1775

C.E. Returning to San Blas Shortly

thereafter, de Ayala

y Aranza enthusiastically reported to the Virrey giving a full account of the geography of the bay. He

reported the fine harbor presented "a beautiful fitness, and it has no lack

of good drinking water and plenty of firewood and ballast." He also

concluded that it possessed a healthful climate and "docile natives lived

there." A chart of the Bay of San

Francisco was prepared by José de Cañizares. In short, he stressed its advantages as a harbor.

This was that chiefly the absence of "those troublesome fogs which we had

daily in Monterey, because the fogs

here hardly reach the entrance of the port, and once inside the harbor, the

weather is very clear." Recognizing the perils that lay before him, Anza

later relocated his military operations from Horcasitas

to Tubac in mid-October of 1775 C.E. It is situated on the Santa

Cruz River. This was the original Spanish Settlement Period guarnición

in Arizona. There he continued preparations. His stay at Tubac

lasted only until October 23, 1775 C.E. Juan

Bautista Anza’s Settlement Expedition departed from the Northern Nueva

España town of Tubac, Arizona on

the route established the preceding year. The Expedition resembling a traveling

village, left with 240 pobladores,

heading to the San Francisco Bay in Alta

California. In the journal he kept of the journey, Anza

recorded the following number of travelers: Comandante

Juan Bautista Anza; Three frayles;

40 Spanish soldados; 29 women who were

the wives of the soldados; one hundred

thirty-six other family members, including children of the soldados

as well as four other volunteer families that did not include soldados;

fifteen Muleteers; seven servants of the frayles

and of Capitán Anza; five Indian

interpreters; three others; and a commissary. Animals in the expedition included

165 pack mules carrying supplies, 320 Horses, and 302 cattle. Their 500-mile

journey would lead them on horseback across rivers, deserts, and snowy

mountains, through territory that had been traveled by only a few Spanish

explorers before them.

With planning and preparation having been

completed, he left with approximately three hundred volunteers and one thousand

head of livestock. Whatever the number, it was a sizable group. They would

finally leave from the final staging area Tubac,

having been delayed by Apache raids.

The Apaches had driven off the entire

herd of 500 horses three weeks prior to the expedition's arrival, forcing it to

continue with no fresh mounts. The contingent had no wagons or carts. All

supplies were loaded on pack mules. This meant that his troops had to load the

mules each morning and unload them when they reached their destination. Food

supplies included six tons of flour, frijoles,

cornmeal, sugar, and chocolate, loaded on and off of pack mules every day.

Materials from cooking kettles to iron for making horseshoes added more tonnage.

The Comendador and his servants had a

tent, as did Fray Font

and his assistants. The families, vaqueros,

muleteers, and soldados shared ten

tents among them. The goal of the Expedition was to establish a

Catholic misión and military presidio

near the mouth of the bay, and to secure the area for the Corona

Española. The Expedition was expected to be so difficult that the Spanish virrey

had to promise to pay for the pobladores’

clothing, food, and supplies for years to come, and still only the poorest

families volunteered, in the hopes of a better life in Alta

California. Most of the people in the group knew they would never again

return to their homes in the settled regions of Méjico.

They had to bring things with them what they would need to survive in the new

land they were going to, a land they had never seen, where no Españoles

had settled before them. The first night out, the group suffered its only

death en route when María Manuela Piñuelas

died from complications after childbirth. Her son lived. Two other babies born

on the trip brought the total number of pobladores to 198. Of these, over half were children 12 years old

and under. At San Xavier del Bac

(located about 10 miles south of today’s downtown Tucson, Arizona), Fray

Font presided over the woman's burial and the marriage of four couples.

Departing from San Xavier del Bac, the expedition left behind the last Spanish

settlement until Misión San Gabriel. Guiding them across Baja California's formidable landscape was no easy task. Anza's

Settlement Expedition slowly made its way northward, up the Santa

Cruz river valley, past what is now present-day Tucson.

It then followed the Gila River west

until it intersected with the Colorado

River. While they camped, Anza, Font,

and a few soldados visited Casa

Grande, which was already known as an ancient Indian site. There were

frequent bouts of sickness affecting the party and its animals. These delayed

progress, as did the birth of a second baby. The Settlement Expedition finally reached the Colorado

River on November 28, 1775 C.E. They were assisted in crossing the Colorado

by Olleyquotequiebe (Salvadór Palma),

chief of the Yumas (Quechan), whose

tribe had befriended Anza on his 1774

C.E. trek. With assistance from the Yumas

it was crossed without incident. On December 4, 1775 C.E., the Anza

Expedition parted company with the Yumas

and Padre Gracés. These stayed behind to begin their misiónero

work. As the party followed the Colorado River west, Anza

divided the Expedition into four separate groups. He did this in hopes that by

staggering the groups, in this way they would each make better use of available

water supply. Anza also thought that

separate groups made for better foraging. The Expedition now constituted three

groups of pobladores and one of

livestock, each traveling one day apart. Mid-December’s weather was unseasonably cold.

Temperatures and weather conditions alternated daily between wet and dry. Life

on the trail was miserable due to these conditions. Clothing became wet and damp

from the rain and snow, increasing the chance of illness. The dry weather caused

thirst for the Expedition. Later, the cattle stampeded resulting in the loss of

fifty cows. This limited the food supply for the pobladores in California.

Just before Christmas, Anza's party

had made their way into Coyote Cañon

what is now Anza Borrego Desert State Park. There they regrouped. On Christmas

Eve a third baby was born. On December 26, 1775 C.E., the Settlement

Expedition finally reached a pass, the gateway to Alta

California. They reached San

Gabriel on January 4, 1776 C.E. Upon the Expedition’s arrival at Misión

San Gabriel Arcángel (In San Gabriel,

California), the European population of Alta

California was doubled. However, Misión

San Gabriel was only to be a stopover. There the Expedition regrouped and later forged

ahead. They finally continued up the Pacific Coast in mid-February, 1776 C.E.

From there they followed known trails through Indian villas along the coast of California,

visiting Misión San Luís Obispo de

Toloso and Misión San António de Padúa.

Misión San António de Padúa is a

Spanish misión was established by the

Franciscan order in present-day Monterey

County, California, near the

present-day town of Jolon. Founded on

July 14, 1771 C.E., it was the third misión

founded in Alta California. The

Expedition remained there longer than anticipated. Due to hostilities between

Spanish pobladores and the Kumeyaay

Indians around San Diego, Anza

was recruited by the Comandante of California, Capitán Fernando Xavier de Rivera y Moncada, to

suppress the rebellion. To their credit, the Capitán Juan Bautista Anza Settlement Expedition arrived in Monterey,

California area from Sonora

on March 10, 1776 C.E. with 240 pobladores

and 1,000 head of domestic stock. It was also in that year that España

named Monterey the official capital of Baja and Alta California.

Anza had arrived with some of the first pobladores for Spanish California

with most of them bound for San Francisco.

Monterey’s soldados and their wives lived at the Royal Presidio (located where the San

Cárlos Cathedral now stands) struggled to create a pueblo and raise families. The Expedition finally reached the Monterey

Presidio and Misión San Cárlos del

Carmelo on While the larger group waited, Anza

took a small group to explore San

Francisco Bay. Although several earlier expeditions had explored the region,

no appropriate site for settlement had yet been determined. By March 23, 1776

C.E., Anza had left his weary fellow sojourners at this location and took

an advanced party from Monterey to

select the new outpost of el Imperio Español.

From there Anza led a party of twenty

men including Fray Pedro Font onward

to the San Francisco Bay to

investigate possible sites for the new presidio. Fray Font was another of the gifted Franciscans to

chronicle early California history,

but only for a short period because he was there in connection with the second Anza

expedition. Born in Geróna, Cataluña,

he came to Méjico in 1763 C.E. Within

a decade, he moved to Sonora as a misiónero

among the Pimas. Upon his return with Anza

in 1776 C.E., he would go to San Miguel de

Ures. There, the Fray completed the short version of the diary that gained

him fame, the longer edition being completed in 1777 C.E. Three years later, Fray

Font would die at Caborca. Font included a map of the Port of San Francisco in his diary. According to an account kept by Fray

Font, on March 27, 1776 C.E., "the weather was fair and clear, a favor

which God granted us during all these days, and especially today, in order that

we might see the harbor which we were going to explore." After a march of

four hours, they "halted on the banks of a lake or spring of very fine

water near the mouth of the port of San

Francisco," today's Mountain Lake. This spot afforded a resting place

for the tired riders. Then, Anza took Fray Pedro Font and four soldados

to scout further. Anza reconnoitered the northern end of the San

Francisco peninsula. Going to the northernmost tip of San

Francisco Bay's peninsula and looking down from Cantil

Blanco or White Cliffs, Anza had

seen enough. He ordered the party back to camp. There, Fray Font set down his somewhat over-optimistic impressions:

"This place and its vicinity has abundant pasturage, plenty of firewood,

and fine water, all good advantage for establishing here the presidio or fort

which is planned. It lacks only timber, for there is not a tree on all those

hills, though the oaks and other trees along the road are not very far away.

Here and near the lake there are "yerba

buena" and so many lilies that I almost had them inside my tent." Font

continued and, for one of the first times, clearly used the term San

Francisco as the name of the great bay: "The port of San

Francisco is a marvel of nature, and might well be called a harbor of

harbors, because of its great capacity, and of several small bays which it

unfolds in its margins or beach and in its islands." Followed the Pacific Coast northward, the

Expedition sighted the bay of San

Francisco on March 28, 1776 C.E. He recommended a mesa overlooking the entrance to the bay as the location of the

projected presidio and the area of Arroyo

de los Dolores on the interior of the bay for the misión.

There he chose sites for the presidio

and the misión. Anza returned to the Cantil

Blanco of the previous day to erect a wooden cross. This was at or near the

present-day toll plaza on the south

side of the Golden Gate Bridge. This action marked the formal act of possession

for España. Anza also selected the ground where the cross stood as the spot for

a presidio to protect the region. Then

the party further surveyed the immediate area. Anza was to follow orders and next explore the

"River of Saint Francis." He would travel the east side of San

Francisco Bay before turning south to return to Monterey. Fray Font recorded: "On leaving we ascended a small

hill and then entered upon a mesa that

was very green and flower-covered, and an abundance of wild violets. The mesa

is very open, of considerable extent, and level, sloping a little toward the

harbor. It must be about half a league wide and somewhat longer, getting

narrower until it ends right at the white cliff. This mesa

affords a most delightful view, for from it one sees a large part of the port

and its islands, as far as the other side, the mouth of the harbor, and of the

sea all that the sight can take in as far as beyond the farallónes.

Indeed, although in my travels I saw very good sites and beautiful in all the

world, for it has the best advantages for founding in it a most beautiful city,

with all the conveniences desired, by land as well as sea, with that harbor so

remarkable and so spacious, in which may be established shipyards, docks, and

anything that might be wished. This mesa

the Comandante selected as the site of

the new settlement and fort which were to be established on this harbor: for,

being on a height, it is so commanding that with muskets it can defend the

entrance to the mouth of the harbor, while a gunshot away it has water to supply

the people, namely, the spring or lake where we halted. The only lack is timber

for large buildings, although for huts and cuarteles and for the stockade of the presidio there are plenty of trees in the groves." A story is recounted about the naming of San

Francisco by California's first historian and the first Franciscan pastor of misión

Dolores, Fray Francisco Palóu. In 1768 C.E., José de Gálvez, the Inspector General

of Méjico, informed Junípero

Serra of the names to be given to the misiónes

to be established in Alta California. Serra remonstrated, saying, "Is there then to be no misión

for Our Father San Francisco?" De

Gálvez jested, "If San Francisco

wants a misión, let him cause his

port to be discovered, and it will be placed there!" As fate would have it,

San Francisco would lead España

to this future port. Seven years after that, Juan

Bautista Anza had marched north from Pueblo

San Diego with a Settlement Expedition to establish a Spanish presidio and misión named

San Francisco. Fray Pedro Font had

accompanied that San Francisco

Settlement Expedition, and kept copious notes about the journey in his journal.

The following excerpts by Fray Font

recount the group’s experiences while traveling from the South Bay Peninsula

through an area which today is the Santa

Clara Valley. They provide some striking images of the world that the Españoles encountered: “Friday, March 29, 1776 C.E. We traveled

through the valley some four leagues to the southeast and southeast by south,

and crossed the arroyo of San

Mateo where it enters the pass through the hills. About a league before this

there came out on our road a very large bear, which the men succeeded in

killing. There are many of these beasts in that country, and they often attack

and do damage to the Indians when they go to hunt, of which I saw many horrible

examples. When he saw us so near, the bear was going along very carelessly on

the slope of a hill, where flight was not very easy. When I saw him so close,

looking at us in suspense, I feared some disaster. But Cabo

Robles fired a shot at him with aim so true that he hit him in the neck. On Saturday, March 30, 1776 C.E, Fray

Pedro Font offered, “On beginning to go around the head of the estuary we

found another villa, Indians from there showed great fear as soon as they saw us,

but it was greatly lessened by giving them glass beads. One of the women, from

the time when she first saw us until we departed, stood at the door of her hut

making gestures like crosses and drawing lines on the ground, at the same time

talking to herself as though praying, and during her prayer she was immobile,

paying no attention to the glass beads which the Comandante offered her.” His task accomplished, Anza decided to return to Monterey

on April 4, 1776 C.E. After this survey of the bay, Anza returned from Monterey

to Méjico, and his second in command,

Teniente José Joaquín Moraga, took

command of the Settlement Expedition to lead it to its final destination.

On April 5, 1776 C.E., the Friday before Palm

Sunday, Señor Comandante Coronel Juan

Bautista Anza explored a creek and lake. This day was traditionally called

the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows (Nuestra

Señora de los Dolores). He gave them both the name "Dolores."

The Misión San Francisco de Asís has as its common name "Misión

Dolores," taken from the name of the now vanished Lake Dolores

and Dolores Creek. However, neither Font

nor Anza would have to deal with the actual establishment of a

settlement since both men left the bay area for Monterey on April 5th, arriving there some three days later, on

April 8th. By April 14, 1776 C.E., at age forty, Anza

and Fray Font left Monterey

for Méjico City. Upon his arrival

there, Anza would receive another

promotion and a new assignment destined to take him away forever from California.

Upon his triumphant return to Méjico

City, Anza was made Comendador

of all the troops in Sonora to be

effective in the fall of 1776 C.E. Anza arrived at the Presidio of Horcasitas in Sonora

on June 1, 1776 C.E. The year-long journey proved difficult. Four

volunteers died that year. One would die from complications associated with

childbirth. The other three died from the plague which struck the town of Horcasitas

while they were there preparing for the journey that summer. In total, there

were nine live births and five miscarriages suffered by volunteers of the

expedition between Culiacán, Sonora,

and San Gabriel, Alta California. The presidio

at San Francisco would be established

in June 1776 C.E., by an expedition which set out in two parts. One, the

original Anza Settlement Expedition

would leave from Monterey and go by

land, the other by sea. The objective of both was the bay named in honor of

Saint Francis of Assisi, hence, San

Francisco. With Anza

having left for Méjico, it fell to José

Joaquín Moraga to lead the final leg of the Settlement Expedition

northward. Moraga would serve as both

as comandante and habilitado

or authorized person/deputy of the Presidio

of San Francisco from its founding

until his death on July 13, 1785 C.E. The son of José

Moraga and María Gaona, he hailed

from Misión Los Santos Ángeles de

Guevavi, in today's Arizona, where

he was born on August 22, 1745 C.E. On June 17, 1776 C.E., Capitán Fernando Xavier de Rivera y Moncada

later relented allowing Teniente

Moraga to finally move the pobladores

from Monterey to San Francisco

Bay to build the presidio and found

the misión. Ten days later, they

achieved their goal. They set about building Misión San Francisco de Aísi. Moraga had departed Monterey

on June 17, 1776 C.E., with some 193 weary

pobladores (both soldados and Ciudádanos,

some with families and other single adventurers) made ready for a new life at San Francisco Bay. Here is an excerpt from Moraga’s correspondence in which he describes that final leg of

the journey: “In the valley of the latter there appeared before us a herd of

elk to the number of eleven, of which we got three without leaving our road.

This merciful act of the infinite providence of the Most High is noteworthy, for

the soldados were by now tired out by

the difficulties of the road and weak on account of the customary fare,

consisting only of maíz and frijoles, on which they were being fed, a reason why the women with

continuous sighs were now making known their great dissatisfaction. But this

refreshment of meat appearing before us, and we being able with such ease to

take advantage of it, the soldados not

only were revived with such a plenty of food, but they were also delighted with

the prospect of the abundance of these animals which the country promised. And

it is certain, most Excellent Sir, that these elk are of such size and have such

savory flesh that neither in quantity nor in quality need they envy the best

beef.” On June 27, 1776 C.E., the land Settlement

Expedition contingent under the command of the Comandante

of the new post, Don José Moraga,

arrived in the neighborhood of the Golden Gate arriving along the shore of Laguna

Dolores, near what is now Albion and Camp Streets in the Mission District.

Two Franciscan padres, Fray Francisco Palóu

and Fray Benito Cambón, accompanied

them. The Expedition had reached the northernmost tip of the San

Francisco peninsula, which Anza

had previously selected as the site for the military presidio. They halted at the site of what became the Misión

Dolores. It included Frayles Palóu

and Cambón, a few married pobladores

with large families, and seventeen dragoons. Moraga's main force had arrived at a Bay Area clearing overlooking

the bay and immediately began work on a chapel and a few crude shelters for the guarnición.

The expedition had carried with them garden seed, agricultural implements,

mules, horses, and sheep. The group would rest there and wait for supplies which

the ship, the San Cárlos. Part of the Land Expedition contingent, Frayles

Palóu and Cambón, five servants, six soldados

and families, and one poblador with

family would remain to manage the Misión

site. Each of the California misiónes

had a group of soldados assigned to it

by the gobernador. Soldados

were sent with the padres each time

permission was granted by the government to establish a new misión.

The job of the soldados was to protect

the misión and the padres. The group of four to six soldados assigned to a misión

under the command of a Cabo was known

as an escolta. The soldados’

were housed in the cuarteles or

headquarters barracks. These buildings were usually separate from the misión compound. Each soldado

was provided a small bed or cot. It was made of a wooden frame with rawhide

tightly stretched over it for a mattress. Cots were arranged in one room,

leaving the soldados little privacy.

The soldado’s uniform and military

equipment were hung on pegs on the wall adjacent to each bed. The misión

soldados were called soldados de cuera

or leather-jackets. This was because of their leather jackets which were

sleeveless vest-type jackets made of six or eight layers of tanned deerskin or

sheepskin. The jacket acted as protection against arrows, which could not

penetrate the thick layers of leather. The soldados

were also equipped with thick leather chaps or leggings to keep their legs from

being cut and scratched when riding through brush. Additional protection was

provided by an adarga or shield which

the soldado carried it on his left

arm. The adarga was composed of two

protective layers of raw oxhide. Most of the misión

soldados were supplied with several horses and a mule. Horses had not been

known in the Nuevo Mundo before the Españoles

arrived. When riding a horse soldados

wore a leather apron. It was fastened to the saddle and hung down on both sides,

covering his legs. The soldados

wore a belt that held bullets and gunpowder across his shoulders. His weapon was

a lanza with a long wooden shaft and a

sharp metal tip, an espada ancha

or short sword with a wide blade, and a short escopeta,

a smoothbore .69 caliber flintlock musket. The flintlock musket was a gun with a

smooth bore inside the barrel. The spark used to set-off the charge was

activated by a flint striking a piece of steel. It wasn’t very accurate when

fired, but easy to load. Under an enramada

or arbor built by Moraga's soldados, Fray

Francisco Palóu celebrated the first Mass on the feast of Saints Peter and

Paul, June 29, 1776 C.E. It is considered the "official birthday" of Misión

San Francisco de Asís and of the city of San Francisco. The Misión

is named after the founder of the Franciscan Order, Giovanni di Pietro di

Bernardone and informally named Francesco, is formally known as Saint Francis of

Assisi (1182 C.E.-1226 C.E.). Founded under the direction of Fray

Junípero Serra, it is the sixth Franciscan misión

to be established in Alta California. The remainder of the Españoles moved about three miles northwest to establish the Presidio

of San Francisco close to the south shore of what is now the Golden

Gate channel. Padre Palóu would

dedicate the site five days before the American Declaration of Independence was

signed. Although they had arrived at their destination,

the pobladores could not begin

construction of the Presidio until the

arrival of the supply ship San Cárlos,

which was delayed in its arrival, taking 42 days to make the voyage from Monterey

due to poor sailing conditions. This delay caused further hardship for the soldados

and their families, as recounted here by Teniente

Moraga: “The boat was now tardy and provisions were getting low, so I

ordered the sargento to prepare four soldados,

two servants, and fifteen mules equipped with pack saddles, so that on the June

30, 1776 C.E., they might go to Monterrey

to request some provisions of Don Fernando

Ribera and at the same time ask him to supply me with some goods, for the soldados

are naked and the cold in these days is severe, and it is a pity to see all the

people shivering, especially since they were raised in hot climates and this

being the first year in which they have experienced the change of temperature.

For this reason I am living in fear that such nakedness may bring upon us some

disastrous sickness. It was now necessary to reduce the ration for the soldados

until the boat should arrive or the pack train return, and, in order that hunger

might not make the people disconsolate, on the same day I detached my sargento

with three soldados and six servants

with the order that, not sparing any effort whatever, he should see if he could

capture some elk, but although he tried hard he was unable to aid us with this

succor.” Moraga would pass the next several weeks actively

exploring the region. On these forays, he concluded that a plain to the

southeast of the Cantil Blanco seemed

better suited for a military outpost. Don

Moraga realized cold fogs often shrouded the windy spot which had been

selected by Anza. He may have desired

a slightly milder climate than the exposed cliffs selected by Anza.

He also sought convenient sources of water, which he found on a good plain in

sight of the harbor and entrance, and also of its interior. As soon as he found

the location the Teniente decided that

it was suitable for settlement. With this in mind, Moraga

relocated the main force to the spot he selected. Without waiting for the

detachment which was coming by sea, the contingent chose a site for the presidio

and began work upon the modest buildings of that station. Seed was planted, the

cattle and sheep were put out to graze, and the horses and mules began their

work. On August 12, 1776 C.E., an Indian attack on

people in the area was carried out by the rival Ssalson tribe. From Padre

Palóu: “The heathens of the villas

of San Mateo, who are their enemies, fell upon them at a large town

about a league from this lagoon, in which there were many wounded and dead on

both sides. Apparently the Indians of this vicinity were defeated, and so

fearful were they of the others that they made tule rafts and all moved to the

shore opposite the Presidio, or to the

mountains on the east side of the bay. We were unable to restrain them, even

though we let them know by signs that they should have no fear, for the soldados

would defend them.” By mid-August 1776 C.E., work at the misión

was on a church and living quarters along with corrales

for herds of cattle and horses. Wheat and vegetable crop areas were also

laid out and turned for planting. In the early stages the main priority was to

survive while awaiting sea borne supplies. During this time Moraga's

force remained in its rudimentary encampment without any special military

preparations. That situation changed when the San

Cárlos, the Spanish packet-boat under

the command of Capitán Juan Manuel de Ayala y

Aranza (December 28,

1745 C.E.-December 30, 1797 C.E.) finally

arrived on August 17, 1776 C.E. After the ship's Capitán, its Piloto and

the ship's Capellán came ashore, they

concurred with Moraga's selection for

the fort and presidio. With this, the Piloto,

Cañizares, laid out: "A square measuring ninety-two varas

(ninety yards square each way) with divisions for church, royal offices,

warehouses, guardhouses, and houses for soldado

pobladores, a map of the plan being formed and drawn by the first Piloto."

To expedite construction a squad of Marineros

and two carpenters was left to join in to complete a warehouse, the Comandancia

and a chapel while the soldados worked

on their own dwellings. The Royal Regulations of 1772 C.E. required that

the presidios be constructed of adobe

brick. This was a suitable material and design for presidios

on the Southern Spanish Provincias

Internas but it was never suitable for the northern climate of Monterey or San Francisco

with their high winds and heavy rains. The Moroccan design was meant for the

arid climate but the Spanish bureaucracy could not adjust to geography. Wooden

or stone buildings were more appropriate for those climates. However the Spanish

soldados followed orders and planned a

design with an adobe wall and bastions

that followed the 1772 C.E. regulations. Consequently, from the beginning the San

Francisco Presidio was subject to continual rebuilding. In future, the Presidio would be dependent on the supply ships from San

Blas for basic food needs and there were often food shortages. The first part of September saw the buildings of

the presidio post substantially

complete. On September 17, 1776 C.E., Teniente José Joaquín Moraga founded the Presidio of San Francisco.

With sufficient progress being made, the San

Cárlos crew joined the soldados

and Ciudádanos and four misiónero