|

Chapter

Twenty-Six

World

War II 1939 C.E.-1945 C.E.

The

de Riberas and the Second World War

I.

Introduction

As this family

history of the de Ribera

family of New Mexico is a story about a Hispano

family, “Chapter Twenty-Six - World War II 1939 C.E.-1945 C.E. - The de Riberas and the Second World War” will deal in the main with

American Hispanic participation in WWII, in particular Nuevo Méjicano Hispanos.

Why? It isn’t that I want to bore the reader with information about

Hispanics however I feel that it’s necessary to clarify for my

children the Hispanic experience which is currently not shared in

America today.

As I’ve used the

term Hispano, I must explain

it. I would suggest that a Hispano

is a person of Spanish descent and considered a native or resident

living in the southwest United States. They are mostly descendants of España’s settlers (Vasco

and Conversos - Spanish Sefardíes

(Jews) converted to Christianity to escape persecution from the Spanish

Inquisition) who immigrated to the northern edges of the Virrey

of Nuéva España.

Additionally, this would apply to those of European extraction, Mestízos, and Indigenous Native Americans living in the area during

the Spanish Colonial Period (1595 C.E.-1821 C.E.) and shared España’s

cultural and religious values.

Hispano

would not apply to those Méjicanos

of European extraction, Mestízos

of mixed Spanish and Native American ancestry having arrived in the

northern edges of the Virrey

of Nuéva España (today’s

American Southwest) during the twenty-five year of the Méjicano occupation period (1821 C.E.-1846 C.E.). The deeply

engrained Spanish cultural traits, integration of local customs, and the

allegiance to España differed

greatly from those immigrants from Méjico

proper. Some Hispanos

continued to differentiate themselves culturally from the population of Méjicano Americans whose ancestors arrived in the Southwest after

the Méjico Revolution of 1821

C.E. which began in Méjico

proper and was enforced upon the outer reaches of Nuéva

España.

Here, I must again

explain what is meant by the term Hispanic American. It is an ethnic term

used to categorize any citizen or resident of the United States, of any

racial background, and of any religion, who has at least one ancestor

from the people of España or

any of the Spanish-speaking countries of the Americas. The three

largest Hispanic groups in the United States are the Méjicano

Americans, Puertorriqueños,

and Cubano Americans. Hispanic

Americans are also referred to as Latinos.

Hispanic Sephardim

Another group of

American Hispanics served as well, Sephardim Jewish soldiers. During World

War II, approximately a half a million American-born Ashkenazi and

Sephardim Jewish soldiers served in the various branches of the United

States armed services and roughly 52,000 of these received U.S. military

awards. The number of Jews in military service in the United States

during World War II out of a total population of 4,770,000 American Jews

was 550,000.

Sephardi Jews, also

known as Sephardic Jews or Sephardim "The Jews

of España," originally

from Sepharad, España or the

Ibero Peninsula, are a Jewish

ethnic division. They established communities throughout areas of modern España and Portugués,

where they traditionally resided, evolving what would become their

distinctive characteristics and diasporic identity, which they

took with them in their exile from Ibero beginning

in the late-15th-Century C.E. to North Africa, Anatolia, the Levant, Southeastern and Southern

Europe, as well as the Americas.

Mikveh Israel in

Philadelphia traces it origins back to the creation of Jewish Communal

Cemetery in 1740 C.E. During the Revolutionary War, Jews from all of the

synagogues fled to Philadelphia, where they joined together under the

leadership of the distinguished Reverend Gershom Méndes

Seixas, the first Jewish minister trained in America. Reverend Seixas

refused to submit to the authority of the British, and was obliged to

flee New York when they took control of Shearith Israel.

Sephardic

immigration during the 19th-Century C.E. was minimal (especially in

comparison with the massive influx of Ashkenazi Jews from Central and

Eastern Europe) but Sephardim continued to be fully involved in the

civic and commercial life of the new nation.

Just prior to the

turn of the century and in the first decades of the 20th-Century C.E.,

an open door policy on the part of the U.S. led to a new influx of

Sephardim from these regions. Estimates suggest that between 24 and 40

thousand Sephardim entered the country at this time. Most of them

remained in the major urban centers of New York, Philadelphia and

Chicago. These waves of immigration are part of the fabric of this

nation’s experience and the Northeastern U.S. has borne witness to the

arrival of representatives from all these migrations. Sephardic Jews,

descendants of Jews expelled from España in 1492 C.E., first settled in

Seattle in 1902 C.E.

For a variety of

reasons, a significant proportion of those immigrants settled in the

state of Washington, ultimately giving Seattle one of the largest

populations of Sephardic Jews in the United States. Since WWI, Seattle

has had the largest percentage of Sephardim compared to the total Jewish

population of any American city.

Those called the

Greatest Generation, responded to the attack on Pearl Harbor with many

American men quickly enlisting. The Sephardim of Seattle were no

different. Sephardic parents rallied around their children who had seen

their duty and took up the American cause. They were proud of their

young Sephardic sons and daughters who were now fighting in the armed

forces.

One of these was

Colonel Jonathan de Sola Méndes,

a Sephardim. He was exemplary member of Congregation Shearith

Israel, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, for the Sephardim

community. De Sola Méndes became a combat pilot and served in World War

II (100 missions; two Air Medals) and the Korean War (70

missions; 8 Air Medals, including the Distinguished Flying Cross),

where he flew the last U.S. Marine Corps mission on July 27,

1953 C.E.

The chapter will

also deal with the world that surrounded these Hispanics. Chapter

Twenty-Six - World War II 1939 C.E.-1945 C.E. “The de

Riberas and the Second World War,” has been a particularly

challenging one for me to write. Anyone who has read this family

history, to date, understands the complexity of each historical period

covered in a chapter. In some cases, the writing format selected to

provide subject matter with clarity has been extremely difficult to

achieve. There have been chapters, in which I have used a narrative

format. In others, I’ve written using both a narrative format with

timeline formats interleaved. In this chapter, I’ve employed the

latter.

In “The de Riberas and the Second World War,” an attempt has been made to

capture the sense of urgency felt worldwide prior to the outbreak of the

war. The Europeans especially, understood very clearly the price such a

war would exact from its combatants, participants, and non-combatants.

For them, the “War to End All Wars” had just ended twenty

years earlier. I found this Anonymous quote which works nicely

here. "History repeats itself because no one was listening the

first time."

While many tried to

prevent it, other actively sought it. In the Western Hemisphere, and

within the United States, particularly, there was both an aversion to it

and a sense that somehow the nations there were exempt from the carnage

about to be visited upon the world due to their geographic isolation.

They would soon be proven wrong in that assumption.

As for the Hispanic

American experience in this chapter, I have made an effort to explain

the duality of both hope and despair that existed for these members of

that great nation, the United States of America of the period. The years

leading up to the War had been difficult for them and other Americans.

The Great Depression and its dramatic economic decline pummeled America.

The “Mexican Repatriation,” that mass deportation of Méjico

and Méjicano Americans

from the United States between 1929 C.E. and 1936 C.E., and to some

lesser degree through to 1940 C.E., was devastating for Hispanics.

The Mexican

Repatriation was the forced return to Méjico

of people of Méjicano

descent (Men, women, and children) from the United States between 1929

C.E. and 1936 C.E. In some cases, the mandate carried out by American

authorities took place without due process. The Immigration and

Naturalization Service targeted Méjicanos in California, Texas, and Colorado because of the

proximity of the Méjicano

border. The physical distinctiveness of Mestízos

and their easily identifiable barrios

made the Hispanic Americans of the West and Southwest particularly

vulnerable. Studies have provided conflicting numbers for how many Méjicanos were repatriated during the Great Depression, but

estimates range from 500,000 to 2 million.

In 2005 C.E., the State of California passed an official

"Apology Act" to those forced to relocate to Méjico,

an estimated 1.2 million of whom were United States citizens.

There was the

rearing of the ugly head of racism. One cannot escape its presence

during the period. Sargent Shriver once said, “We must treat the

disease of racism. This means we must understand the disease.” I agree

with his statement. Here it must be said that even this ugliness was in

the process of being overcome by Americans. To the degree that any

nation can say that it has attempted to address these issues the U.S.

certainly has tried to do so in many ways. Were the remedies perfect?

No! Could they have been better? The answer is, yes. At issue here is

not national perfection, for man is an imperfect creature. What is of

importance here is the fact that America has always tried to remedy ills

and improve the lives of its people, all its people.

What will become

glaringly clear to the reader is that despite its failings in the matter

of Hispanic American mistreatment, there were improvements for all

citizens of the United States. When one looks at the improvement in

upward mobility in the U.S. Armed forces, it is factual to say that

Hispanic Americans achieved upward mobility in rank and opportunity.

It is also safe to

say that Hispanic American love of country despite it failings, is

clearly demonstrated in the numbers of these men and women who joined

the ranks of the American military during WWII.

The two sections,

WWII between the Axis Powers and the Allies and the United States in

Europe- December 8, 1941 C.E.- May 9, 1945 C.E. and WWII between the

Axis Power Japan and the United States in the Pacific - December 8, 1941

C.E.-September 2, 1945 C.E., provide the American experience during

actual war fighting.

The tragedy of the

Second World War cannot be overstated. It was butchery on the highest

level and led to carnage on an almost unimaginable scale. To be sure,

not all Americans wanted this war. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR)

had kept the nation neutral until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on

December 7, 1941 C.E. Once this heinous act was perpetrated, war was

forced upon America and its people. By that year, the population of the

United States was 133.4 million. More than 12 million Americans

would serve in the U.S. armed forces between 1941 C.E. and 1945 C.E.

This means that roughly 11% of all Americans served in WWII. That is a

remarkable number of draftees and enlistees.

Along with White,

Black, Asian, and other groups, Hispanic Americans served in all

elements of the American armed forces in WWII and fought in every major

American battle of that war. They entered into the military either as

volunteers or via the draft. To be frank, the exact number of

Hispanics who participated in WWII is unknown. At the time, Hispanics

were not tabulated as a separate group, but instead were included in the

general White population census count. Separate statistics were

designated and maintained for both African Americans and Asian

Americans.

When the United

States officially entered the war on December 8, 1941 C.E., among those

American citizens who joined the ranks of the U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine

Corps many were Hispanics. They served as active combatants in the

European and Pacific Theatres of war and as part of the military

industrial complex on the home front as civilians. Hispanic

women joined the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAACs) and the

Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES). They served

as nurses, in administrative positions of all types, and other areas.

Many replaced men who had worked in manufacturing plants that produced

munitions and materiel while they were away at war.

Many Hispanic

Americans served in the U.S. Armed Forces during WWII. It is

estimated between 250,000 and 500,000 were involved. This

constitutes 2.3% to 4.7% of the U.S. military. Of the more than 500,000

Hispanics that served, 350,000 were of Méjicano

Américano origin and 53,000 Puertorriqueños.

Of those designated as being of Méjicano

Américano origin, we have in previous chapters identified them as Californios,

Tejanos, Nuevo Méjicano

Hispanos, and other Hispanics. This is because they were the

earliest settlers of today’s American areas of the West and the

Southwest. These had been for over 200 years under España,

as the Virriento of Nuéva

España until 1821 C.E. Until 1848 C.E., for 25 years these lands

were under Méjico. Obviously,

after them, there were many new Hispanic arrivals.

Approximately, 9,000

Hispanics are believed to have died in WWII in the defense of the United

States. Unfortunately, the lack of specified documentation

identifying Hispanics as a group makes it difficult to assess the total

number of Hispanic Americans who died in the conflict.

The following table

provides information regarding Méjicano

Origin/Hispanic/Latino Origin

percentages by each of the four regions of the United States and the

total for the United States for the years 1910 C.E.-2010 C.E. The 1940

C.E. Percentage was only 1.4% of the total U.S. population.

If there was “0”

growth in the Hispanic population of the United States after 1940 C.E.,

the nation’s Hispanic population would be approximately 1,960,000 in

1945 C.E. If during WWII between 250,000 and 500,000

Hispanic Americans served in the U.S. Armed Forces that would

represent a very large portion for that population.

|

Percentage

of population of Mexican origin (1910–1930) and of Hispanic/Latino

origin (1940–2010) by U.S. state

|

|

State/territory

|

1910

|

1920

|

1930

|

1940

|

1950

|

1960

|

1970

|

1980

|

1990

|

2000

|

2010

|

|

United States of

America

|

0.4%

|

0.7%

|

1.2%

|

1.4%

|

|

|

4.7%

|

6.4%

|

9.0%

|

12.5%

|

16.3%

|

|

Northeast

|

0.0%

|

0.0%

|

0.0%

|

0.4%

|

|

|

4.1%

|

5.3%

|

7.4%

|

9.8%

|

12.6%

|

|

Midwest

|

0.0%

|

0.1%

|

0.3%

|

0.2%

|

|

|

1.5%

|

2.2%

|

2.9%

|

4.9%

|

7.0%

|

|

South

|

1.1%

|

1.7%

|

2.5%

|

1.9%

|

|

|

4.4%

|

5.9%

|

7.9%

|

11.6%

|

15.9%

|

|

West

|

1.9%

|

3.1%

|

5.4%

|

6.1%

|

|

|

11.3%

|

14.5%

|

19.1%

|

24.3%

|

28.6%

|

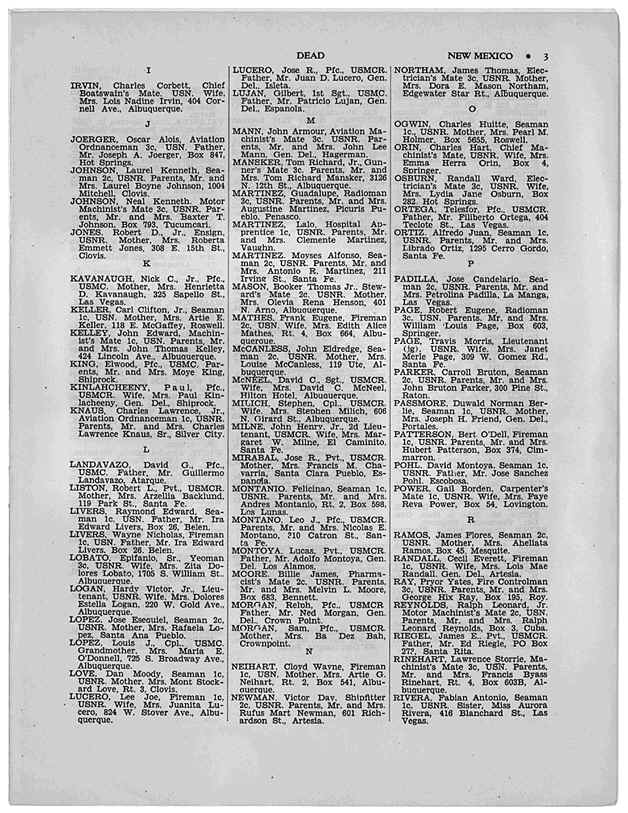

In my mother’s

native state of New Mexico, by 1940 C.E., there were just over 530,000

people living there. That number would not be substantially higher after

December 7, 1941 C.E. For the United States, WWII would last nearly

four years until 1945 C.E. During that period, 49,579 New Mexican men

and women would volunteer or be drafted into military service. That

would represent 0.09 percent of the population. Many of these were Hispanos.

It should be noted that New Mexico had both the highest volunteer rate

and the highest casualty rate of all of the forty-eight states of the

Union. In fact, New Mexico soldiers were some of the first Americans to

see combat during the war.

In an effort to

provide the magnitude of the United States’ World War II Casualties

I’ve provided the following table:

|

War

or Conflict

|

Branch

of Service

|

Number

Serving

|

Total

Deaths

|

Battle

Deaths

|

Other

Deaths

|

Wounds

Not Mortal

|

|

World

War II

|

Total

|

16,112,566

|

405,399

|

291,557

|

113,842

|

670,846

|

| |

Army

|

11,260,000

|

318,274

|

234,874

|

83,400

|

565,861

|

| |

Navy

|

4,183,466

|

62,614

|

36,950

|

25,664

|

37,778

|

| |

Marines

|

669,100

|

24,511

|

19,733

|

4,778

|

67,207

|

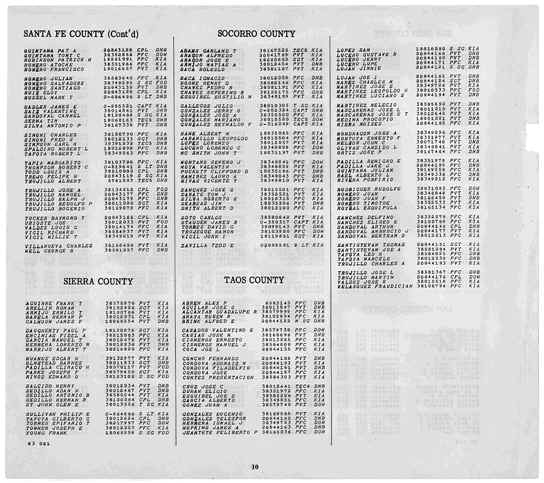

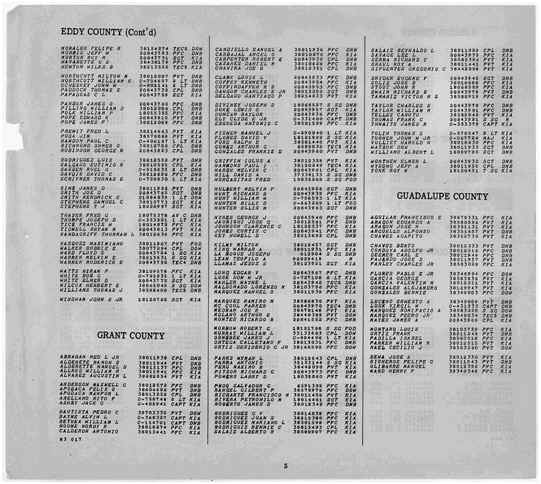

The following two

tables provide New Mexico’s World War II Casualties:

|

Army

and Air Forces

|

New

Mexico

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County

|

Killed

in Action (KIA)

|

Died

of Wounds (DOW)

|

Died

of Injuries (DOI)

|

Died,

Non-Battle (DNB)

|

Finding

of Death (FOD)

|

Missing

in Action (MIA)

|

Total

|

|

Bernalillo

|

160

|

12

|

1

|

163

|

17

|

1

|

354

|

|

Catron

|

6

|

2

|

|

4

|

|

2

|

14

|

|

Cháves

|

58

|

4

|

|

23

|

7

|

1

|

93

|

|

Colfax

|

27

|

4

|

|

25

|

5

|

|

61

|

|

Curry

|

29

|

5

|

|

43

|

5

|

2

|

84

|

|

De

Baca

|

7

|

3

|

|

7

|

1

|

|

18

|

|

Doña

Ana

|

53

|

3

|

1

|

28

|

12

|

1

|

98

|

|

Eddy

|

54

|

6

|

|

53

|

3

|

|

116

|

|

Grant

|

55

|

5

|

|

43

|

3

|

2

|

108

|

|

Guadalupe

|

15

|

4

|

|

10

|

|

|

29

|

|

Harding

|

8

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

|

13

|

|

Hidalgo

|

9

|

1

|

|

4

|

|

|

14

|

|

Lea

|

27

|

5

|

|

29

|

4

|

|

65

|

|

Lincoln

|

21

|

|

|

12

|

1

|

|

34

|

|

Luna

|

26

|

4

|

1

|

21

|

5

|

1

|

58

|

|

McKinley

|

51

|

6

|

|

41

|

5

|

|

103

|

|

Mora

|

29

|

3

|

|

9

|

|

|

41

|

|

Otero

|

19

|

1

|

|

15

|

2

|

|

37

|

|

Quay

|

12

|

4

|

|

7

|

1

|

|

24

|

|

Río

Arriba

|

32

|

1

|

|

20

|

7

|

|

60

|

|

Roosevelt

|

22

|

3

|

|

17

|

3

|

|

45

|

|

Sandoval

|

21

|

4

|

|

15

|

|

1

|

41

|

|

San

Juan

|

22

|

6

|

|

14

|

3

|

|

45

|

|

San

Miguel

|

42

|

5

|

|

22

|

2

|

|

71

|

|

Santa

Fé

|

59

|

6

|

|

47

|

5

|

|

117

|

|

Sierra

|

14

|

1

|

|

7

|

3

|

|

25

|

|

Socorro

|

23

|

4

|

|

9

|

|

|

36

|

|

Taos

|

36

|

6

|

|

26

|

1

|

|

69

|

|

Torrance

|

17

|

4

|

|

10

|

2

|

|

33

|

|

Union

|

16

|

1

|

|

10

|

4

|

|

31

|

|

València

|

46

|

5

|

|

31

|

|

|

82

|

|

State at Large

|

7

|

|

|

3

|

2

|

1

|

13

|

|

Total

|

1,023

|

120

|

3

|

771

|

105

|

10

|

2032

|

|

Navy,

Marine Corps, and Coast Guard

|

|

|

Type

|

Total

|

|

Killed

in Action (KIA)

|

219

|

|

Killed

in Prison Camps

|

5

|

|

Missing

in Action (MIA)

|

7

|

|

Wounded

in Action (WIA)

|

330

|

|

Released

from Prison Camps

|

19

|

|

Total

|

580

|

Before we enter into

the main body of the chapter, I would like to provide a broad brush

approach for those Hispanics that served in various areas of the world

and within the U.S.

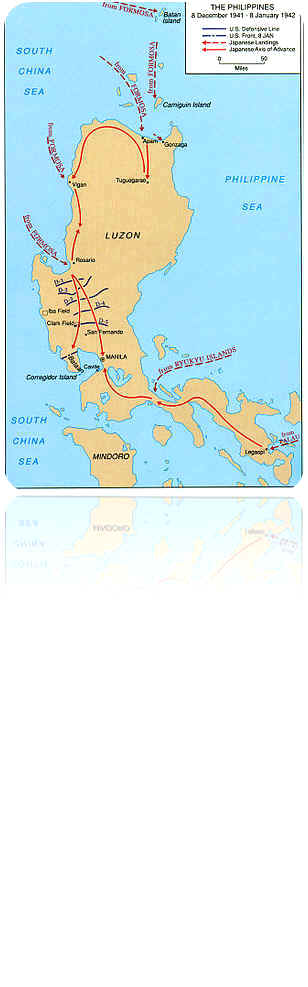

The exact numbers of

Hispanics who served in WWII is difficult to obtain. With the exception

of the 65th Infantry Regiment from Puerto

Rico, Hispanics were not segregated into separate units, as African

Americans were. Hispanics served with distinction throughout Europe, in

the Pacific Theater, North Africa, the Aleutians, and the Mediterranean.

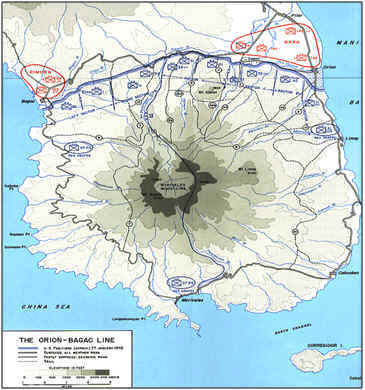

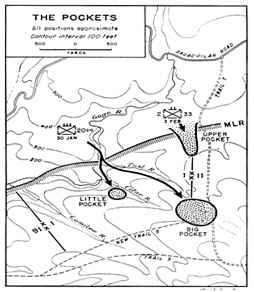

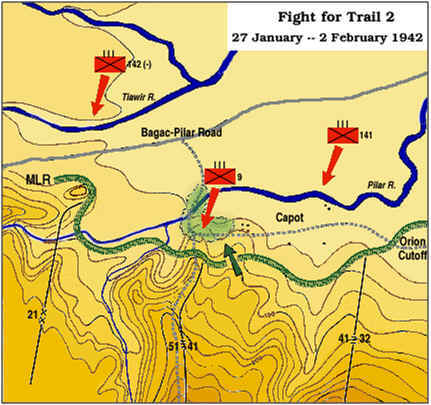

In the Pacific Theater, the 158th Regimental Combat Team, had a large

percentage was Hispanics and Native American. They fought in New Guinea

and the Philippines. Hispanic soldiers were of particular assistance in

the defense of the Philippines as many were fluent in Spanish which was

invaluable when serving with Spanish speaking Filipinos. Some of these

took a part in the infamous “Bataan Death March.”

In the European

Theater, Hispanic soldiers from the Texas 36th Infantry Division were

among the first soldiers to land on Italian soil and suffered heavy

casualties crossing the Rapido River at Cassino. The 88th Infantry

Division with draftees from Southwestern states was ranked in the top 10

for combat effectiveness.

While I cannot list

all Hispanics that served, I’m providing the names of just a few. As

I’ve spent most of the previous chapters on ground forces, here I will

offer some of the names of who served in the United States Army Air

Forces (USAAF), the U.S. Navy, and the U.S. Marine Corps.

There were also WWII

Hispanic Flying Aces. A "flying ace" or fighter ace is a

military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft

during aerial combat. The term "ace in a day" is used to

designate a fighter pilot who has shot down five or more enemy aircraft

in a single day. Since World War I, a number of pilots have been

honored as "Ace in a Day".

European

Theater

Among the Hispanics

who played an instrumental role as a commander during the conflict was

Lieutenant-General Elwood R. "Pete" Quesada,

(1904 C.E.-1993 C.E.). Elwood Richard Quesada

was born in Washington, D.C. in 1904 C.E. to an Irish American mother

and a Spanish father. He attended Wyoming Seminary in

Kingston, Pa., University of Maryland, College Park, and Georgetown

University.

Then

Brigadier-General Quesada was

assigned in October 1940 C.E. to intelligence in the Office of

the Chief of Air Corps. By December 1942 C.E., The Brigadier-General

took over the First Air Defense Wing to North Africa. Shortly

thereafter, he was given command of the XII Fighter Command where he

would work out the operational aspects of close air support and

Army-Air Force cooperation. The successful integration of air and land

forces in the Tunisia campaign forged by Quesada

and the Allied leaders became a blueprint for operations incorporated

into Army Air Forces field regulations. It has been stated that it

provided the Allies with their first victory in the European war. He was

the foremost proponent of "the inherent flexibility of air

power", a principle he helped prove during World War II.

In October 1943 C.E.,

Quesada assumed command of the

IX Fighter Command in England.

His forces would

later provide air cover for the landings on Normandy Beach. On D-Day plus

one, he was commanding general of the 9th Fighter Command. Quesada

established advanced headquarters on the Normandy beachhead and

directed his planes in aerial cover and air support for the Allied

invasion of the European continent. Among Brigadier General Quesada's

many military decorations were the Distinguished Service Medal with oak

leaf cluster, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Purple Heart, and an

Air Medal with two Silver Star devices.

Captain Michael Brezas,

USAAF fighter ace, arrived in Lucera, Italy, during the summer

of 1944 C.E., joining the 48th Fighter Squadron of the 14th Fighter

Group. Flying the P-38aircraft, then Lieutenant Brezas

downed 12 enemy planes within two months. He received the Silver Star

Medal, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Air Medal with eleven oak

leaf clusters.

U.S.

Brigadier-General Alberto A.

Nido (March 1, 1919 C.E.-October 27, 1991 C.E.) was a former United

States Air Force officer who during World War II served

in the Royal Canadian Air Force, the British Royal Air

Force (RAF), and in the United States Army Air Forces. He was

also the co-founder of the Puerto

Rico Air National Guard. He was born and raised in the town of Arroyo in Puerto

Rico. There he received his primary and secondary education. In 1938

C.E., he enrolled in the University of Puerto

Rico and studied mechanical engineering in the institution's Mayagüez Campus.

During World

War II, then Captain Nido flew

missions as a bomber pilot for the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

On December 24, 1942 C.E., Nido

was sent to London, England, and participated on the European

Theater of the war as a bomber pilot. Canadian fighter-bombers

attacked coastal areas in German-occupied Europe while Canadian heavy

bombers struck at targets much further inland.

Nido

was transferred to 610 Squadron of the British RAF on January

10, 1943 C.E. and participated in various combat missions as a Supermarine

Spitfire fighter pilot for the RAF. Lieutenant Nido, Alberto A. USAAC (Puerto

Rico) was on detachment to 610 Squadron of the British RAF on

January 10, 1943 C.E. He flew a Spitfire V BL850 on October 14, 1943 C.E.

on Circus 56; flew EE753 on Rodeo in 1943 C.E.; flew AD577 on Convoy

Patrol on October 20, 1943 C.E.; He flew BL990 on Naval Patrol October

23, 1943 C.E.; He flew AD348 on Shipping Recco on October 24, 1943 C.E.;

He flew Escort to Ramrod 94 (Cherbourg) in AD348 October 24/10/1943 C.E.;

He flew AD557 on Escort to Ramrod 95 on October 25, 1943 C.E.; flew

BL787 on Circus to Guipavas Airfield on October 26, 1943 C.E.; He flew

AD577 on Patrol 26/10/1943 C.E.; flew BL787 on Ramrod to Cherbourg on

October 27, 1943 C.E.; He made a forced landing because of engine

failure in Spitfire Vc EE615 at ‘Halfway House’ on Langport to

Somerton Road, Somerset while operating from Bolt Head and was

uninjured. He flew AD271 on Recco to Sept Isles October 11, 1943 C.E.;

He flew AD577 on Convoy Patrol November 11, 1943 C.E.;

Nido

returned to his RCAF home unit on November 16, 1943 C.E. He was among 10

pilots of the 67th Reconnaissance Squadron who were sent to weather

school at RAF Zeals under the command of Colonel T. S.

Moorman. His unit participated in 275 combat missions.

Later, in 1943 C.E.,

Nido and 59 other American

pilots were transferred to the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF). He was

assigned to the 67th Fighter Group as a P-51 Mustang fighter

pilot. Nido baptized his P-51 with the name of "Alile" in honor

of the girl that he left back home. He was awarded the Distinguished

Flying Cross with four oak leaf clusters and the Air Medal

with four oak leaf clusters.

Technical Sergeant

Clement Resto, USAAF, served

with the 303rd Bomb Group during WWII. He was not an "ace" but

participated in numerous bombing raids over Germany. During a bombing

mission over Duren, Germany, Resto's

B-17 plane was shot down and lost an eye during that last mission. Resto

was captured by the Gestapo and sent to Stalag XVII-B where

he spent the rest of the war as a prisoner of war. After the Technical

Sergeant was liberated from captivity, he was awarded a Purple Heart, a POW

Medal, and an Air Medal with one battle star.

Pacific

and Asian Theaters

Robert Ribera was born on May 11, 1929 C.E., in Ribera, New Mexico. He passed away on October 16, 2001 C.E., in

Phoenix, Ariz. His father was Apolonio

Ribera and his mother was María

Justa Ribera. He served his country in the U.S. Army during World

War II, serving in the Pacific Theater. Mr. Ribera

worked for the City of Phoenix for a number of years. After retirement

he resided in Camp Verde,

Arizona.

Lieutenant José

António Muñiz Vásquez served with distinction in the China-Burma-India

Theater. He was born in Ponce,

Puerto Rico. That was where he received his primary and secondary

education. He also attended the "Colegio

Ponceño de Varones" in Ponce

and later the University of Puerto

Rico (UPR). During his student years, he was a member of that

institutions Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) program.

During his WWII tour of duty he flew 20 combat missions against the Imperial

Japanese Army Air Force and shot down a Mitsubishi A6M Zero. José

António Muñiz Vásquez was also a co-founded the Puerto

Rico Air National Guard together with then-Colonels Alberto A. Nido and Mihiel

Gilormini.

Staff Sergeant Eva

Romero Jacques was one of the first Hispanic women to serve in the

USAAF. Jacques had three years of college and spoke both in Spanish and

in English. She spent two years in the Pacific Theater. Eva spent 1944

C.E. in New Guinea and was in the Philippines1945 C.E., as an

administrative aide. She survived a plane disaster when the craft in

which she was on crashed in the jungles of New Guinea.

European

Theater

U.S.

Army, U.S. Army Air Force and U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Navy

U.S.

Army

Major-General Terry

de la Mesa Allen Sr. (April

1, 1888 C.E.-September 12, 1969 C.E.) was a senior USA officer who

served from 1912 C.E. through 1946 C.E. who fought in both World

War I and World War II. Major-General de la Mesa Allen Sr., or "Terrible Terry" as he was

know, was born in Fort Douglas, Utah, to Colonel Samuel Edward Allen and

Consuelo "Conchita" Álvarez de la

Mesa and died at the age of 81. Allen's family had a long line of

military tradition. Besides his father, Allen's maternal grandfather,

Colonel Cárlos Álvarez de la

Mesa, was a Spanish national who fought at Gettysburg for

the Union Army in the Spanish Company of the "Garibaldi

Guard," during the American Civil War it was known officially

as the 39th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Five months after

the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent German declaration

of war on the United States, in May 1942 C.E., de

la Mesa Allen was promoted to the rank of major-general and given

command of the 1st Infantry Division. Allen's 1st Infantry Division

was soon sent to the United Kingdom where they underwent

further combat training, which included training in amphibious operations.

Allen's brash and informal leadership style won him much respect and

loyalty from the men in his division, who wholeheartedly adopted his

emphasis on aggressiveness and combat effectiveness rather than military

appearances.

Later, from May 1942

C.E. until August 1943 C.E. Allen was the commanding general of the 1st

Infantry Division in North Africa and Sicily. He

was later selected to lead the 104th Infantry Division as

divisional commander, a post he held until the end of the war.

While commander of

the 104th Infantry Division in North Africa, Allen and his deputy

1st Division Commander, Brigadier-General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., distinguished

themselves as combat leaders. Allen was re-assigned to the 104th

Infantry Division. The 104th Infantry Division landed in France on

September 7, 1944 C.E. and fought for 195 consecutive days during World

War II. The division's nickname came from its timber wolf shoulder

insignia. Some 34,000 men served with the division under Allen. The

division was particularly renowned for its night fighting prowess.

Fourteen months

after the United States declared war against Germany and

entered World War I, on June 7, 1918 C.E., Allen was sent to France and

assigned to the 315th Ammunition Train.

Later, Allen was assigned to the 3rd Battalion of the 358th

Infantry Regiment, part of the 90th Division of the American

Expeditionary Force (AEF) which he led into battle on the Western

Front at Saint Mihiel and Aincreville. During one battle,

Allen received a bullet through his jaw and mouth. He was awarded a Silver

Star and a Purple Heart for his actions. Allen remained

with the AEF in France until the Armistice of November 11, 1918 C.E.

He then served with the Army of Occupation in Germany until 1920

C.E. when he returned to the United States.

After Allen returned

to the United States, his temporary rank of major was reverted to

captain until July 1, 1920 C.E., when he was promoted to the permanent

rank of major. He served in Camp Travis and later in Fort McIntosh,

both located in Texas. In 1922 C.E., Allen was assigned to the 61st

Cavalry Division, in New York City.

He continued to take

military related courses. In 1928 C.E., he married Mary Frances Robinson

of El Paso, Texas, with

whom in 1929 C.E. he had a son, Terry Allen, Jr. On August 1,

1935, Allen was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and became an

instructor at the U.S. Army Cavalry School at Fort Riley, Kansas.

In 1939 C.E., he wrote and published "Reconnaissance by horse

cavalry regiments and smaller units"

During World

War II while the United States was still neutral, on October

1, 1940 C.E., General George C. Marshall, Jr., the U.S. Army

Chief of Staff, promoted him to the rank of brigadier-general, even

though he had not held the rank of colonel. He then commanded the 3rd

Cavalry Brigade. From April through May of 1941 C.E., he commanded the 2nd

Cavalry Division. He then became the assistant division commander (ADC)

of the 36th Infantry Division, an Army National Guard formation

from Texas. The 36th Division was commanded by his good friend,

Brigadier General Fred L. Walker.

Army

Air Force

In 1941 C.E., Rear

Admiral Luís de Flórez (March

4, 1889 C.E.-November, 1962 C.E.) was from New York City. De Flórez attended MIT, and graduated in 1911 C.E. with a B.S.

in Mechanical Engineering. He was a naval aviator in the United

States Navy that was actively involved in experimental aerospace

development projects for the United States Government. During World War

II, he was promoted to Captain and in 1944 C.E., to Rear Admiral.

As both an active

duty and a retired U.S. Navy admiral,

de Flórez was influential in the development of early flight

simulators, and was a pioneer in the use of "virtual reality"

to simulate flight and combat situations in World War II. He also played

an instrumental role in the establishment of the Special Devices

Division of the Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics. De

Flórez was later assigned as head of the new Special Devices Desk

in the Engineering Division of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics. The

Admiral was also credited with over sixty inventions.

U.S.

Marine Corps

See the Pacific and

Asia Theaters

U.S.

Navy

United States Navy

Rear Admiral José M.

Cabanillas (September 23, 1901 C.E.-September 15, 1979 C.E.)

participated in the invasions of North Africa and in the

invasion of Normandy on D-Day during the Battle of Normandy World

War II. Cabanillas was born to José

C. Cabanillas and Asunción

Grau de Cabanillas in the city of Mayagüez,

which is located in the western coast of Puerto

Rico. There he received his primary and secondary education. In 1917

C.E., at the age of 16, he was sent to Alabama to attend the Marion

Military Institute. In the school he underwent a two-year preparatory

course which prepared him for the United States Naval Academy. Cabanillas

graduated from the Institute in 1919 C.E. On June 16, 1920 C.E., he

received an appointment from the U.S.-appointed governor of Puerto

Rico to attend the United States Naval Academy from 1913 C.E.

to 1921 C.E. Cabanillas

graduated from the Naval Academy on June 4, 1924 C.E. He was

commissioned an ensign in the U.S. Navy.

Prior to World War

II, Cabanillas served aboard

various cruisers, destroyers and submarines. Among

the battleships that he served in were the U.S.S. Florida, U.S.S.

Colorado and U.S.S. Oklahoma. From June 1927 C.E. through

January 1928 C.E., the Ensign received instruction in submarines at

the Submarine Base, New London, Connecticut, after which he served

on the U.S.S. S-3 until May 1930 C.E. Cabanillas then earned a Master of Science in June 1932 C.E. from Yale

University.

In 1942 C.E., upon

the outbreak of World War II, then Captain

José M. Cabanillas was assigned as Executive Officer of the U.S.S.

Texas (BB-35). The U.S.S. Texas was by then the oldest remaining dreadnought

and was one of only two remaining ships to have served in both world

wars at that time. On November 8, 1942 C.E., the Texas participated

in the invasion of North Africa by destroying an ammunition

dump near Port Lyautey. Cabanillas

also participated in the invasion of Normandy on (D-Day). On June 6,

1944 C.E., the ship went to work on another target on the western end of "Omaha"

beach. Cabanillas was awarded

the Bronze Star Medal with Combat "V," for "meritorious

achievement and outstanding performance of duty as executive officer of

the U.S.S. Texas during the Invasion of Normandy and the bombardment of

Cherbourg. He had taken over ship control in the conning tower

after an enemy shell had destroyed the bridge. As this was the primary

control station, Captain Cabanillas

rendered invaluable service to his commanding officer in the performance

of the assigned mission.

In 1945 C.E., Cabanillas

became the first Commanding officer of the U.S.S. Grundy (APA-111),

which was commissioned on January 3, 1945 C.E. The Grundy helped

in the evacuation of Americans from China during the Chinese Civil

War. In December 1945 C.E., he was reassigned to Naval Station

Norfolk located in Norfolk, Virginia, as Assistant Chief of Staff

(Discipline), 5th Naval District.

U.S. Navy Rear

Admiral Edmund Ernest García (March

25, 1905 C.E.-November 2, 1971 C.E.) was born to Enríque García and Antónia

Rumírez in San Juan,

Puerto Rico. There he received both his primary and secondary

education. García was born

into a family with a long tradition of military service. His father, Enríque García, was a Captain in the United States

Army. In 1922 C.E., García graduated

from high school and received an appointment to the United States

Naval Academy from the appointed Governor of Puerto Rico. García was

supposed to graduate from the Naval Academy in 1926 C.E. He graduated

and received his commission of Ensign on June 17, 1927 C.E.

During World

War II, then Lieutenant Commander García commanded the Edsall-class destroyer escort U.S.S.

Sloat (DE-245) The Sloat was launched on January 21, 1943 C.E.

From June 15th to July 15, 1943 C.E. the Sloat operated in the

Caribbean and Atlantic Ocean in search of German U-boats. He

also participated in the invasions of North Africa, Sicily,

and France.

Before WWII, García

served from 1927 C.E. through 1928 C.E. as an artillery officer aboard

the U.S.S. Wyoming and was later assigned to the U.S.S.

Galveston. In 1928 C.E., he was trained as a naval aviator at Pensacola,

Florida. García received

addition training in various military institutions which included the

Torpedo School of San Diego,

California. From 1932 C.E. through 1939 C.E. García served on the warships New Mexico, Heron, Asheville, and

the Tulsa. During these years, he also served as flight instructor

at Naval Aviation School in Pensacola

between 1935 C.E. to 1937 C.E. By 1939 C.E., he was reassigned to Fort

Mifflin, Pennsylvania, where he helped prepare and equip the U.S.S.

Hornet. García worked on various aircraft carriers until 1941 C.E.,

when the United States entered World War II.

Pacific

and Asia Theaters

U.S.

Army, U.S. Army Air Force and U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Navy

U.S.

Army

These are covered in

the main body of the chapter.

U.S.

Army Air Force

Rear Admiral Henry

G. Sánchez commanded (as a

Lieutenant Commander) VF-72, an F4F squadron of 37 aircraft, on board

the U.S.S. Hornet (CV-8) from July through October

1942 C.E. His squadron was responsible for shooting down 38 Japanese

airplanes during his command tour, which included the Battle of the

Santa Cruz Islands.

U.S.

Marine Corps

As part of the war

against Japan the Americans launched the Mariana and Palau Islands

Campaign’s from June 15, 1944 C.E. through July 9, 1944 C.E. in Saipan, Mariana

Islands. Guam and Saipan landings in the Marianas followed.

Guy Gabaldón of New Mexico ancestry was one of the U.S. Marines that

participated in Saipan the landings and the military action that

followed. He had tried to enlist in the Marine Corps, but, at 16, he was

underage. He later joined the Marine Corps and boot camp qualified him

to be a scout observer. A year later, June 15, 1944 C.E., now 18 years

old, after rigorous amphibious training he was made Marine Private in

the 2nd Marine Division in the Saipan-Tinan Operation in the South

Pacific.

Early in July 1944

C.E., Gabaldón conducted what

would become his most famous exploit. He went off on his own, on an

"evening patrol" to convince Japanese soldiers to surrender.

This time, as the day dawned, he realized that enemy troops were

gathering around his unit for what would prove to be one of the largest

suicide charges of the war. The next day, after the end of "banzai

charge," he was cut off from retreat. Gabaldón

captured two Japanese guards and persuaded them to return to the caves

below, where other soldiers and civilians were camped. He next found

himself among hundreds of Japanese.

Gabaldón

worked to convince the Japanese with his "street Japanese" and

confident air that if they surrendered they would avoid torture and

death and receive medical attention and food rations. Soon a Japanese

officer and some of his men were the first of many to surrender to Gabaldón en masse. Other Japanese, many women and children, chose

to jump off nearby cliffs, to avoid the torture they had been warned by

Japanese officers would await them at the hands of the Americans.

Gabaldón

has been credited by comrades with capturing 800 Japanese on that one

day. This “Pied Piper of Saipan," Gabaldón’s

exploits have been confirmed by his comrades. Later, Gabaldón was wounded on Saipan and shipped to a naval hospital in

Hawaii. He next boarded the hospital ship back to California.

Guy Gabaldón was born in 1926 C.E., the fourth of seven children. He

was raised in Boyle Heights, a neighborhood of East Los Ángeles. There he grew up in a tiny house and spent much of his

time on the streets. At that time, Boyle Heights' diverse population

included Jews, Russians, Armenians, Chicanos

and Méjicanos and was

harmonious. His father worked as a welder and a machinist for the

Pacific Freight Express at the time and his mother stayed home looking

after the children. His life of adventure began when he was only 10

years old and shining shoes on the mean streets of downtown Los

Ángeles from Skid Row, to Main Street to Broadway and Hill. His

parents were only vaguely aware of what he was doing during the day.

He was a carefree

10-year-old with unlimited access. There were times when he'd walk in to

the bars on Main Street, run errands for bar girls and make a nickel or

so. Once in a while he would grab a beer. The bottom line was that he

was street smart and this instinct would hold him in good stead during

World War II.

He was 12 when he

met two Japanese American brothers: Lyle and Lane Nakano. All three of

them were around the same age and went to the same school. Gabaldón

was drawn to the Nakano boys because they excelled in school work, were

honest and never got into trouble with the law. Fascinated by their

traditions and customs, he began spending a lot of time at their home

and eventually moved in with them. He was a surrogate son for the

Nakanos - in a manner of speaking - and Gabaldón's

parents didn't object to this.

It was around this

time that he started getting into trouble with the tough crowd in Boyle

Heights. He began sneaked cigarettes, went "joyriding" in

cars, and generally was mischievous. Things started getting out of hand

and one day Gabaldón was

caught by the cops and sent to juvenile detention for two weeks. His

mother went to court and pleaded with the judge to release him with the

assurance that she would send him to New Mexico with relatives.

He soon found

himself with his nearly blind grandfather who owned a cantina

called Tinaja in New Mexico. Gabaldón's

80-year-old paternal grandfather lived alone in the cold country up in

New Mexico, between Gallup and Grants, near Inscription Rock. He gave Gabaldón

a little Palomino mare and a .22 shotgun and a .44 that he kept close to

his bed. Gabaldón found the

gun-keeping strange but soon found out why it was necessary. Grandfather

Gabaldón had some pretty

rough characters coming in at odd hours - no wonder he'd make sure that

the shotgun was loaded.

Meanwhile, his

uncle, Sam, a postmaster at San

Rafael, would drive with young Gabaldón

to Grants every morning to pick up the mailbags. Often he'd be allowed

to drive and, before he was 13, he got his driver's license. After

spending a few months in New Mexico, Gabaldón

was back in Boyle Heights with the Nakanos. He stayed with them for

almost seven years until the U.S. entered the war in 1941 C.E. and the

Japanese family was sent to an internment camp.

The first of

Hispanic settlement in the Río

Tesuque area occurred in 1732 C.E. after the de

Vargas Reconquista of 1693

C.E. when Antónia Montoya

sold Juan de Benavides a piece

of land containing much of what is now Tesuque.

EI Rancho Benavides extended

from the current southern boundary of Tesuque

Pueblo to the junction of the Big and Little Tesuque Rivers between the mountain ridges on the east and west of

the river. EI Rancho Benavides

became known as San Ysidro,

who is the patron saint of farmers. The name is still used for the local

church today.

The first we hear of

the Gabaldón name is when António

Gabaldón of Puebla, Nuéva España, applied to enter the Franciscan convent of San

Francisco de Puebla in 1716 C.E. We next find a, Juan

Manuel Gabaldón of Santa Fé,

Santa Fé County, New Mexico since 1737 C.E., acting as attorney for

Catalina Varela de Losada,

living in Chihuahua. António

Gabaldón was involved in her land proceedings in the matter of

convey in land by Joseph García 1739 C.E. at Santa Fé,

Santa Fé County, New Mexico.

Later on July 31,

1744 C.E., we find a Juan Gabaldón

the Jémez Alcalde handling a

complaint to Governor for Nicolás

Aragón and his wife of Bernalillo.

In 1752 C.E., a Juan

de Gabaldón obtained much of the Río

Tesuque region in a land grant from the Spanish Territorial

Governor. He had been unable to find farmland near Santa

Fé because of a scarcity of irrigation water (Wozniak 1987). The

watershed of the Río Tesuque sustained Pueblo

of Tesuque villagers and

Spanish settlers providing a route into the nearby Sangre

de Cristo Mountains for seasonal livestock herding, hunting and the

gathering of firewood, piñones and other food resources and raw

materials. By 1776 C.E., Fray

Francisco Domínguez visited Río

de Tesuque village and documented that it contained 17 families with

94 people.

The last information

that I have on the New Mexico Gabaldóns

is that of Cárlos Gabaldón.

He attended my

Great-Grandfather, Anastácio’s

wedding in Pecos, New Mexico,

to Catalina Barela (his

second) on February 17, 1890 C.E. Cárlos

was listed as a Padrino or

Sponsor of the wedding.

A Hispanic American

and U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant-General Pedro

Augusto del Valle (1893 C.E.-1978 C.E.), served as the

commanding general of the 1st Marine Division during World War II and

became the Hispanic to attain the rank of Lieutenant-General. Born in Puerto Rico while it was still under Spanish rule, his family moved

to Maryland in 1900 C.E. After graduating from high school in 1911 C.E.,

he received an appointment by Puertorriqueño

governor George Colton to attend the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis,

Maryland. In June 1915 C.E., he graduated from the academy and was

commissioned a second lieutenant of the Marine Corps.

Del

Valle was a Colonel and the

Commanding Officer of the 11th Marine Regiment (artillery) in

March 1941 C.E. After the outbreak of World War II, he led his regiment

and participated in the Guadalcanal Campaign, providing critical artillery support for the

1st Marine Division. He led his regiment during the seizure and defense

of Guadalcanal, providing

artillery support for the 1st Marine Division. In the Battle

of the Tenaru, on August 21, 1942 C.E., the firepower provided by his

artillery units killed many assaulting Japanese soldiers, almost to the

last man, before they ever reached the Marine positions at the Battle of

the Tenaru.

General Alexander

Vandegrift, impressed with del

Valle's leadership, recommended his promotion and on October 1, 1942

C.E., del Valle became a

Brigadier-General. He was retained as head of the 11th Marines, the only

time that the regiment has ever had a general as their commanding

officer. In 1943 C.E., he served as Commander of Marine Forces

overseeing Guadalcanal, Tulagi,

and the Russell and Florida Islands.

In April 1944, as

Commanding General of the Third Corps Artillery, III Marine Amphibious

Corps, del Valle participated

in the Battle of Guam and was awarded a Gold Star in lieu of a

second Legion of Merit. In late October 1944 C.E., he succeeded

Major-General William H. Rupertus as Commanding General of the 1st

Marine Division, which was training on the island of Pavuvu for the

invasion of Okinawa. He was personally greeted to his new command by the

famous Colonel Lewis Burwell "Chesty" Puller.

By May 29, 1945 C.E.,

del Valle participated in one

of the most important events that led to victory in Okinawa. After five

weeks of fighting, del Valle

ordered Company A of the 1st Battalion 5th Marines to capture Shuri

Castle, a medieval fortress of the ancient Ryukyuan kings. Seizure

of Shuri Castle represented a blow to the morale of the Japanese and was

a milestone in the Okinawa campaign. Del

Valle was awarded a Distinguished Service Medal for his

leadership during the battle, the subsequent occupation, and

reorganization of Okinawa.

In 1916 C.E., he had

participated in the capture of Santo

Domíngo, Domínícano Republic and during World War I, he commanded

a Marine detachment on board the U.S.S. Texas in the North Atlantic and

participated in the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet in 1919 C.E.

Del Valle served as aide-de-camp to Major General Joseph Henry

Pendleton after serving on a tour of sea duty aboard the U.S.S. Wyoming.

In 1926 C.E., he

served with the Gendarmerie of Haiti for three years during which time

he became active in the war against Augusto

César Sandino in Nicaragua.

In 1929 C.E., he returned to the U.S. and attended the Field Officers

Course at the Marine Corps School in Quantico, Virginia. In 1931 C.E.,

he was appointed to the "Landing Operations Text Board" in

Quantico, which was the first organizational step taken by the Marines

to develop a working doctrine for amphibious assault. By 1933 C.E.,

following the Cubano

Sergeant's Revolt, del Valle

was assigned to Habana, Cuba

as an intelligence officer.

From 1935 C.E. to

1937 C.E., del Valle was the

Assistant Naval Attaché, attached to the American Embassy to Rome,

Italy. While there, he participated as an observer with the Italian

Forces during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. In 1939 C.E. he attended

the Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. After

graduating he was named Executive Officer of the U.S. Marine Corps

Division of Plans and Policies, Washington D.C.

After the end of

World War II, he returned to the U.S., where del

Valle was named Inspector General, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps,

Washington D.C. He retired in that position at the rank of

lieutenant-general in January 1948 C.E., with nearly 33 years of

continued military service in the U.S. Marine Corps. Among his military

decorations and awards include the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, and

Legion of Merit with one award star, the Navy and Marine Corps Medal,

the navy Presidential Unit Citation with one service star, the Marine

Corps Expeditionary Medal with one service star, the Domínícano

Campaign Medal, the World War I Victory Medal, the Haitian Campaign

Medal (1921 C.E.), the Nicaragüense

Campaign Medal (1933), the American Defense Service Medal, the American

Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with five service

stars, the World War II Victory Medal, the Order of the Crown of Italy,

the Colonial Order of the Star of Italy, the Italian Bronze Medal of

Military Valor, and the Cubano

Order of Naval Merit, 2nd class.

U.S.

Navy

When the Empire

of Japan attacked the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl

Harbor on December 7, 1941 C.E., many sailors with Hispanic surnames

were among those who perished. The next day, when the U.S.

officially entered World War II, Hispanic Americans were among those

many American citizens who joined the ranks of the Navy as volunteers or

through the draft. Of the Hispanics who served actively in the

European and Pacific Theaters of war, five would eventually earn the

rank of Rear Admiral and above.

Admiral Horacio

Rivero, Jr. (May 16, 1910

C.E.-September 24, 2000 C.E.), was the first Puertorriqueño and Hispanic four-star admiral, and

the second Hispanic after the American Civil War Admiral David

Glasgow Farragut (1801

C.E.-1870 C.E.), to hold that rank in the modern United States

Navy. After retiring from the Navy, Rivero

served as the U.S. Ambassador to España

(1972 C.E.-1974 C.E.), and was also the first Hispanic to hold that

position.

He served aboard the U.S.S. San

Juan (CL-54) and was involved in providing artillery cover for Marines landing

on Guadalcanal, Marshall Islands, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. For

his service he was awarded the Bronze Star with Combat

"V" ("V" stands for valor in combat). Rivero was reassigned to the U.S.S. Pittsburgh (CA-72) and

is credited with saving his ship without a single life lost when the

ship's bow had been torn off during a typhoon. He was awarded the Legion

of Merit for his actions. Rivero

also participated in the Battle of Santa

Cruz Islands, the attack on Bougainville in the Solomons, the

capture of the Gilbert Islands and a series of carrier raids on Rabaul.

On June 5, 1945 C.E., Rivero was present during the first carrier raids against Tokyo

during operations in the vicinity of Nansei Shoto. Rivero, served as a technical assistant on the Staff of Commander

Joint Task Force One for Operation Crossroads from February 1946 C.E. to

June 1947 C.E., and was on the Staff of Commander, Joint Task Force

Seven during the atomic weapons tests in Eniwetok in

1948 C.E.

On February 23, 1945

C.E., António F. Moreno a

Navy medical corpsman assigned to the 2d Platoon, Company E, 27th Marine

Regiment, witnessed the first flag raising photographed by Staff

Sergeant Louis R. Lowery and the second flag raising

photographed by Joe Rosenthal on Mount Suribachi. On

March 8, 1945 C.E., Moreno,

tried to save the life of Lieutenant Jack Lummus after Lummus

had stepped on a land mine a few feet away from Moreno.

Lieutenant Lummus was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Captain Marion

Frederic Ramírez de Arellano (1913

C.E.-1980 C.E.) was the first Hispanic submarine commanding officer. Participated

in five war patrols, he led the effort to rescue five Navy pilots and

one enlisted gunner off Wake Island. After a brief stint at the Mare

Island Naval Shipyard, de Arellano was

reassigned to the U.S.S. Skate, a Balao-class submarine.

The Captain participated in the Skate’s first three war patrols.

He was awarded a second Silver Star Medal for his contribution in

sinking the Japanese light cruiser Agano on his third

patrol. The Captain also contributed to the sinking of two Japanese

freighters and damaging a third. For his actions, he was awarded a Legion

of Merit Medal.

In April 1944 C.E., de

Arellano was named Commanding Officer of the U.S.S.

Balao. He participated in his ship's war patrols 5, 6, and 7. On July 5,

1944 C.E., de Arellano led the

rescue of three downed Navy pilots in the Palau area. On December 4,

1944 C.E., the Balao departed from Pearl Harbor to patrol in

the Yellow Sea. The Balao engaged and sunk the Japanese cargo

ship Daigo Maru on January 8, 1945 C.E. De Arellano was awarded a Bronze Star Medal with Combat V and

a Letter of Commendation.

These are some of

the members of the de Ribera

Clan of New Mexico that served in the United States navy during WWII.

Pacific

and Asian Theater

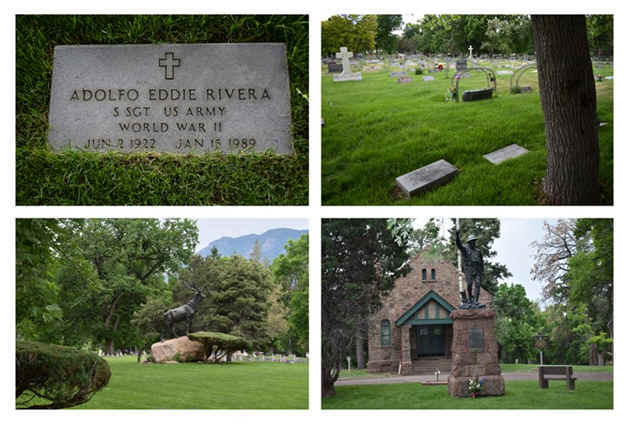

Pete Rivera Santa Fé, New Mexico

Santa Fe National

Cemetery

501 North Guadalupe Street

Santa Fé, NM 87501

Section: 3

Site: 1C

Birth: October 4,

1924

Death: July 14, 2003

Age: 78

Branch: U.S. NAVY

Rank: SA1

War: WORLD WAR II

Pete Rivera SA1, Santa

Fé, NM

Tony Maes Rivera Santa Fé, New Mexico

Santa Fe National

Cemetery

501 North Guadalupe Street

Santa Fé, NM 87501

Section: 14

Site: 111

Birth: August 19,

1918

Death: February 24,

2006

Age: 87

Branch: U.S. NAVY

Rank: AS

War: WORLD WAR II

Tony Rivera AS, Santa

Fé, NM

WWII U.S. ARMY

Private Air Corps, U.S. NAVY Félix

Rivera of Colfax, New Mexico, a member of the de

Ribera Clan and enlisted on February 13, 1946 C.E.

Félix

Rivera Santa Fé, New

Mexico

Santa Fe National

Cemetery

501 North Guadalupe Street

Santa Fé, NM 87501

Section: 18

Site: 19

Birth: January 3,

1929

Death: April 17,

2010

Age: 81

Branch: U.S. ARMY,

U.S. NAVY

Rank: PVT, SN

War: WORLD WAR II

Félix Rivera PVT, SN, Santa Fé,

NM

Enlistment

Information:

Name: Félix Rivera

Serial Number:

18207984

State: New Mexico

County Colfax

Rank: Private

Branch: Air Corps

Army: Regular Army -

Officers, Enlisted Men, and Nurses

Birth Year: 1929

Enlist Date:

02-13-1946

Enlistment Place

Santa

Fé New Mexico

Term: Enlistment for

Hawaiian Department

Nativity: New Mexico

Race: White

Citizenship: Citizen

Education: 1 Year

High School

Civilian Occupation:

Tinsmiths, Coppersmiths, and Sheet Metal Workers

Marital Status:

Single

Dependents: No

Dependents

Enlistment Source:

Enlisted Man, Regular Army, After 3 Months of Discharge

Conflict Period:

WWII, World War 2

Summary: Abstract

for Félix Rivera -

Brief overview of enlistment file

Louis U Rivera Santa Fé, New

Mexico

Santa Fe National

Cemetery

501 North Guadalupe Street

Santa Fé, NM 87501

Section: 6

Site: 3043

Birth: February 11,

1920

Death: September 24,

2000

Age: 80

Branch: U.S. NAVY

Rank: S2

War: WORLD WAR II

Louis Rivera S2, Santa

Fé, NM

Porfirio

Estrada Rivera Santa Fé,

New Mexico

Santa Fe National

Cemetery

501 North Guadalupe Street

Santa Fé, NM 87501

Section: 9

Site: 103

Birth: September 15,

1925

Death: July 10, 1995

Age: 69

Branch: U.S. ARMY,

U.S. NAVY

Rank: CPL, AD3

War: WORLD WAR II,

KOREA

Porfirio Rivera CPL,

AD3, Santa Fé, NM

II.

America and the Lull before the Storm - September 1, 1939 C.E.-December

7, 1941 C.E.

It is important to

remember that many Americans firmly discounted the likelihood of

American involvement in another major war, except perhaps with Japan.

Isolationist strength in Congress had led to the passage of the

Neutrality Act of 1937, making it unlawful for the United States to

trade with belligerents. American policy during the 1930s C.E. was aimed

at continental defense and designated the U.S. Navy as the first line of

such defense. The U.S. Army's role was strictly to serve as the nucleus

of a mass mobilization that would defeat any invaders who managed to

fight their way past the Navy and the nation's powerful coastal defense

installations.

Though the National

Defense Act of 1920 allowed an Army of 280,000, the largest in peacetime

history, until 1939 C.E. the U.S. Congress didn’t appropriate funds to

pay for more than half that strength. Most of the funds available for

new equipment went to the fledgling air corps. Throughout most of the

interwar period, the Army was small and isolated. It was filled with

hard-bitten, long-serving volunteers scattered in small garrisons

throughout the continental United States, Hawaii, the Philippines, and Panamá.

There was some U.S.

military innovation, planning, and preparation for the future which took

place in the interwar U.S. Army. Unfortunately, unlike the Germany, the

U.S. Army’s experimentation with armored vehicles and motorization,

air-ground cooperation, and the aerial transport of troops came to

nothing for lack of resources and high-level support. The Army did,

however, develop an interest in amphibious warfare and in related

techniques that were then being pioneered by the U.S. Marine Corps.

Since the end of

WWI, there had been important developments in the use of tanks. A number

of students of war believed that armored vehicles held the key to

restoring decision to the battlefield. But only the Germans conceived

the idea of massing tanks in division-size units, with infantry,

artillery, engineers, and other supporting arms mechanized and all

moving at the same pace. Moreover, only the German’s General Oswald

Lutz and General Heinz Wilhelm Guderian received the

enthusiastic support of their government.

In general, the

slow-tempo, attritional fighting of WWI, heavily influenced French

military doctrine at the outbreak of WWII. This would be the undoing of

France. During WWII, when the German invasion of France and the Low

Countries began it was called the Battle of France. More to

the point it was the Fall of France.

By the outbreak of

war the U.S. military Signal Corps had become a leader in improving

radio communications, and American artillery practiced the most

sophisticated fire-direction and control techniques. In addition, war

plans for various contingencies had been drawn up, as had industrial and

manpower mobilization plans. Also during the early 1930s C.E. Colonel

George C. Marshall, assistant commandant of the Infantry School at Fort

Benning, Georgia, had designated a number of younger officers for

leadership positions. Despite such preparations, the Army as a whole was

unready when WWII broke out in Europe in 1939 C.E.

In the spring of

1940 C.E., theories in the use of tanks were put to the test as German

forces struck against Norway and Denmark in April. When the Germans

invaded the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg on May 10, 1940 C.E.,

their forces’ land operations on the Western Front would defeat the

Allied forces by the use mobile operations. Later in the same month,

they broke through a hilly, wooded district in France. Their columns

sliced through to the English Channel, cutting off British and French

troops in northern France and Belgium. By then the French Army was

plagued by low morale, a divided command, and primitive communications.

Their army simply fell apart.

Mussolini’s Italy entered

the war on the side of Germany on June 10, 1940 C.E., when she invaded

France over the Alps. The British quickly evacuated their forces

from Dunkirk with the loss of most of their equipment. The Germans

entered Paris four days later on June 14th, and the French government,

defeatist and deeply divided politically, sued for an armistice. The

success of the German Blitzkrieg forced the remaining

combatants to rethink their doctrine and restructure their armies.

By June 22nd, the Second

Armistice at Compiègne was signed by France and Germany and a he

neutral Vichy government led by Marshal Philippe Pétain superseded

the Third Republic. Germany then occupied the north and

west coasts of France and their hinterlands.

Italy took control of a small occupation zone in the

south-east. The Vichy regime retained the unoccupied territory in the

south, known as the zone libre.

Hitler had been

eager to follow up his victory over Poland in 1939 C.E. by attacking in

the west. Bad weather forced the planned offensive to be postponed. By

January 1940 C.E., a German plane carrying a copy of the attack orders

on board crashed in neutral Belgium. This forced Hitler to rethink his

plan. With his initial plan

probably compromised, Hitler turned for advice to General Erich von

Manstein. Tacitus has written that “All empires become arrogant. It is

their nature.” “Great empires are not maintained by

timidity.” The Allies were timid, the Germans were not!

The General urged a

daring campaign. Von Manstein recognizing that a direct attack from

Germany on the Maginot Line was too formidable, he proposed a subsidiary

attack through neutral Holland and Belgium. The lethal blow against

France was to be launched a later through the Ardennes a hilly and

heavily forested area on the German-Belgian-French border. He felt the

Allies would be unlikely to expect an attack. The plan was to rely

heavily on surprise blitzkrieg techniques or “lightning

war.”

Von Manstein's

envisioned to disrupting and disorienting the Allies with the use of

Panzer divisions in a semi-independent role, striking ahead of the main

body of the army. The plan was very risky, much more ambitious than the

strategy used in Poland. The more conservative-minded German generals

were opposed. Hitler gave his approval, but not without some

reservations. Interestingly, the Germans had fewer tanks than the

Allies. Germany had only 2,500 Tanks and the Allies 3,500. The tanks

were concentrated into Panzer armored formations. The French had some

equivalent formations that were of good quality. Their failing was that

they were dispersed rather than concentrated in the German concentrated

formation. Von Manstein's Plan worked. The 1940 C.E. defeat of the

powerful French army in a mere six weeks stands as one of the most

remarkable military campaigns in history.

Unfortunately, in

1939 C.E., as World War Two loomed, the British and French Allies

planned to fight an updated version of the 1914 C.E. through 1918 C.E.

World War One. This was to be done with only some essential differences.

The French had suffered massive casualties in frontal attacks in 1914

C.E. This time they were going to remain on the defensive in Western

Europe. It was their plan to take the offensive two to three years after

the start of hostilities.

The crude trenches

of WWI were replaced by the “Maginot Line.” This was where they

would stand and fight. The Line consisted of a sophisticated series of

fortifications placed to protect France's frontier with Germany. The

crucial Line did not cover the Franco-Belgian frontier. The Germans knew

this and had used it.

With the fall of

France, the government evacuated from Paris to the town of Vichy in the

unoccupied "Free Zone" or Zone Libre in the southern part of

metropolitan France, about 220 miles to the south. While Paris

remained the de jure capital of France, Vichy became the de facto

capital of the French State. It remained responsible for the civil

administration of all France as well as the French colonial empire. The

Vichy regime was the nominal government of all of France except for

Alsace-Lorraine, as the Germans had militarily occupied northern France.

Vichy France or the Régime de Vichy would be headed by Marshal Philippe

Pétain during WWII (From 1940 C.E. to 1942 C.E.) and would never join

the Axis alliance.

After being

appointed Premier by President Albert Lebrun, Marshal Pétain's cabinet

agreed to end the war and signed an Armistice with Germany on June 22,

1940 C.E. Pétain subsequently established an authoritarian regime when

the National Assembly of the French Third Republic granted him full

powers on July 10, 1940 C.E. At that point, the Third Republic was

dissolved.

The German

occupation was to be a provisional state of affairs, pending the

conclusion of the war, which in 1940 C.E. appeared imminent. During the

occupation, France maintained a degree of independence and neutrality.

The regime also kept the French Navy and French colonial empire under

its control. In addition, the Vichy regime had avoided the full

occupation of the country by Germany.

Germany kept two

million French soldiers prisoner and used them as forced Labor. These

were also kept as hostages to ensure that Vichy would reduce its

military forces and pay a heavy tribute in gold, food, and supplies to

Germany.

French police were

ordered to round up Jews and other "undesirables" such as

communists and political refugees. Much of the French public initially

supported the government, despite its undemocratic nature and its

difficult position vis-à-vis the Germans, often seeing it as necessary

to maintain a degree of French autonomy and territorial integrity.

Calling for

"National Regeneration," the French government at Vichy

reversed many liberal policies and began tight supervision of the

economy, with central planning a key feature. Labor unions came under

tight government control. The independence of women was reversed, with

an emphasis put on motherhood. Conservative Catholics became prominent

and clerical input in schools resumed. Paris lost its avant-garde status

in European art and culture.