|

Chapter

Twenty-Seven - The de Riberas and the Korean War (June 25, 1950 C.E.-July 27, 1953 C.E.)

Thanks to all of those sources provided by the Internet and used in this chapter

With this submission of this my last chapter of

the family history of the de

Ribera’s, Chapter

Twenty-Seven - The de Riberas and the Korean War (June 25, 1950 C.E.-July

27, 1953 C.E.) - We fought for the Right reasons, at the Right time, in the Right place,

I’m saying good bye to many years of effort and the joy of finding

one’s ancestral roots. Like many of the hedonistic children of the

1950s C.E. and 1960s C.E., I gave little thought to my family’s past.

I lived in the present and planned for the future. Before this effort

the word “family” was just a cliché. The word family now has a

markedly different meaning for me.

What a gift this work has been. I can now

almost feel the presence of those many ancestors I researched. I feel

that I know them and have learned to love them. So here, I say “à

plus tard,” until later, rather than “Adieu,” to this work. It

would only be appropriate to thank Mimi Lozano

Holtzman and her husband Win of Somos

Primos E-Magazine fame for her kind support and insightful guidance

into the world of history and genealogy. I call Mimi “Dearest”

because she’s a dear soul! Without her this homage to my Mums family,

the de Riberas, would never

have been written.

Now to the de

Riberas and the Korean War!

As Chapter

Twenty-Seven - The de Riberas and the Korean War (June 25, 1950 C.E.-July

27, 1953 C.E.) is the last chapter of the book of the Family History of

the de Riberas of New Mexico,

I wish to present some personal insight as to why this Hispano

American family fought so willingly for the United States of America

(U.S.).

Firstly, I would suggest that it was the

yearning for “Freedom.” It should be remembered that the de Riberas and many of the other founding families of Nuevo

Méjico were Sephardim or Spanish Jews and also Conversos.

During the Spanish Period, they had escaped España

and its religious and political elite to the safety of the Nuevo Mundo, the Américas.

The family made its way ever northward within the Virrey of Nuéva España,

until reaching Nuevo Méjico.

In that desolate place they found safety as hidden Jews, away for

the Inquisición Española. It

was there that these Sefardita

Jews who immigrated into northern areas of the Virrey of Nuéva España

became los Manitos de Nuevo Méjico.

They then ventured to south and central Tejas,

and later to parts of southern Colorado

and beyond. They would

eventually be called, Los Tejanos

y los Manitos de Nuevo Méjico or The Texans and the brethren of New

Mexico. There in what is today the American Southwest the Sephardi

Españoles found the freedom they so desperately wanted.

The de

Ribera blood lines of the North American Continent began when el

Imperio Español sent an expedition under Don

Juan de Oñate to establish the Spanish provincia

de Santa Fé de Nuevo Méjico in 1598 C.E., with a capital founded near Ohkay

Oweenge Pueblo, which he

called San Juan de los Caballeros. De

Oñate later attempted to

establish a settlement in Arizona in 1599 C.E., but failed. They turned

back due to inclement weather. By 1610 C.E., Santa

Fé was founded, making it the oldest capital in U.S. After

arriving, these Españoles

took what they wanted from the indigenous without regard for their needs

and wants.

To be sure, during the 17th-Century C.E., they

would have heard the news of the de

Ribera family in the capital of

Nuéva España, Méjico

City, having been arrested in connection with the trial of Gabriel

de Granada by the Inquisición in Nuéva

España, now Méjico. In

that trial (1642 C.E.-1645 C.E.) there appeared as

"accomplices" in the observance of the Law of Moses and as

Judaizing heretics, the names of Doña

María, Doña Catalina, Clara, Margarita,

Ysabel, and Doña Blanca de

Rivera, all of whom seem to have been natives of Sevilla. Another person mentioned in the same connection is Diego

López Rivera, one of the Sefarditas

from his native Portugués.

The name is frequently written "Ribera."

The reality of religious intolerance and the

fear of the Inquisición Española

had never left them. These Sephardic families understood the

imperfections of el Imperio Español

and the orthodox Católicos of

the Church. The threat these powerful entities represented to the

precious freedom these Sefardí had

sought was palpable.

Almost immediately after the 1821 C.E. invasion

by the Méjicanos, the Españoles

could see the failings of el

Imperio

Méjicano, and

later its replacement governments called the Méjicano Republics. The de

Riberas were forced to accept their conquest and repression by a

foreign power. This continued until Méjico

lost the northern reaches of what had been once the Virrey of Nuéva España

to the Américanos in 1846 C.E.

By 1846 C.E., the Américanos arrived taking the land and making it part of the U.S. I

think that they understood and liked these strong, open, and resourceful

Américanos who were driven by

their “American Dream.” I believe this is why the de

Riberas accepted this new government and became Américanos. Over time, the many generations of the de

Ribera family were not unlike other Americans. To be sure, they

understood the difficulties of a nation that was ever changing and given

to mistakes, but also one which moved ever forward improving itself and

the lives of its people. This was also their dream. Now as Américanos,

they were free to live as they wanted.

I feel it was that belief in “freedom” and

in the “American Dream” that drove their ready participation in the

many American wars, in service to these ideals even, if the nation

itself had glaring faults.

Finally, the de Riberas had always been soldados.

They had served el Imperio Español,

el Imperio Méjicano and later its replacement governments,

and now they entered military service of this great nation, the U.S. of

America. The family served their new country in every war, including the

Korean War. Why would they have done this? I believe it was their love

of country, a belief in “freedom,” and faith in the “American

Dream.”

After 1920 C.E., the family like many other

Americans suffered and served through WWI, the bad economic conditions

of the Great Depression, and WWII. By the time of the Korean War in 1950

C.E., the de

Riberas of

New Mexico had generations of American military service. They understood

what was at stake. Once again, they were willing to serve and die if

necessary for the “Dream.” I am positive that they would have agreed

with this quote by Thomas Jefferson. “With all the imperfections of

our present government, it is without comparison the best existing, or

that ever did exist.” Thomas Jefferson also said this, “We will be

soldiers, so our sons may be farmers, so their sons may be artists.”

This the de Riberas had always done.

Here, I must say that I’ve been asked several

times why I refer to the de

Riberas of New Mexico as a “Clan.” The Rivera

(originally de Ribera) family

name is listed in the New Mexico Office of the State Historian as one of

the founding families of the state. Salvadór

Matías de Ribera (later spelled Rivera)

was the founding progenitor of the New Mexico Riberas.

Salvadór served in the

Spanish Military at the Presidio

in Santa Fé. He was born

in Puerto de Santa María in

Southwest España near Cádiz. The town of Ribera,

New Mexico, is named after him.

In New Mexico, those of the Spanish-speaking

population of colonial descent such as the de

Riberas are referred to by the predominant Spanish term Hispano.

This is analogous to those from California, Californio, and those

from Texas, or Tejano. In New

Mexico, this Spanish-speaking population was always proportionally

greater than those of California and Texas. The term is commonly used to

differentiate those who settled the area early, around 1598 C.E. to 1848

C.E., from later Mexican migrants.

Currently, the majority of the Hispano

population is distributed between New Mexico and Southern Colorado.

A community of people in Southern Colorado who migrated there in the

early 19th-Century C.E. are descended from Hispanos

from New Mexico. Most of New Mexico's Hispanos,

numbering in the hundreds of thousands, live in the northern half of the

state. The predominant ancestry claimed by the state's citizens is that

of descendants of Spanish settlers.

It is accepted that the de Riberas of New Mexico

and Colorado are a group of families the heads of which claim descent

from a common ancestor, Salvadór

Matías de Ribera. This group of people is of a common descent, a

family, a clan.

These are just a few of the de

Ribera Clan who fought in

both WWII

and Korea.

In Korea, “We fought for the Right reasons, at the Right time, in

the Right place”

One of the de Ribera Clan fought in both

WWII and Korea.

His name, U.S. ARMY S SGT Philip Fidel

Rivera Santa Fé, New Mexico,

enlisted on January 6, 1941 C.E.

Philip Fidel

Rivera Santa Fé, New

Mexico

Santa Fe National Cemetery

501 North Guadalupe Street

Santa Fé, NM 87501

Section: V

Site: 1873

Birth: May 1, 1918

Death: September 21, 1970

Age: 52

Branch: U.S. ARMY

Rank: S SGT

War: WORLD WAR II, KOREA

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

501 North Guadalupe Street Santa Fé,

NM 87501

A second member of the de Ribera Clan Porfirio

Estrada Rivera fought in both in WW II and Korea. In Korea he served

in the U.S. Navy.

Porfirio

Estrada Rivera Santa Fé, New Mexico

Santa Fe National Cemetery

501 North Guadalupe Street

Santa Fé, NM 87501

Section: 9

Site: 103

Birth: September 15, 1925

Death: July 10, 1995

Age: 69

Branch: US ARMY, US NAVY

Rank: CPL, AD3

War: WORLD WAR II, KOREA

Porfirio Rivera CPL,

AD3, Santa Fé, NM

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501 North Guadalupe Street Santa Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA, PORFIRIO ESTRADA

|

|

AD3 U.S. NAVY

|

|

CPL U.S. ARMY

|

|

WORLD WAR II, KOREA

|

|

DATE OF BIRTH: 09/15/1925

|

|

DATE OF DEATH: 07/10/1995

|

|

BURIED AT: SECTION 9 SITE 103

|

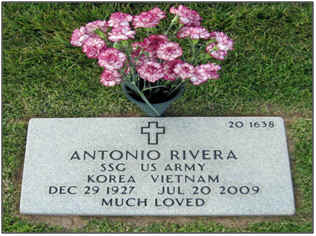

A third member of the de Ribera Clan António

Rivera fought in both

Korea and Vietnam.

He served in the

U.S. Army.

|

SANTA FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501 North Guadalupe Street Santa Fé,

NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA,

ANTÓNIO

|

|

SGT

U.S. ARMY

|

|

KOREA,

VIETNAM

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 12/29/1927

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 07/20/2009

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION 20 SITE 1638

|

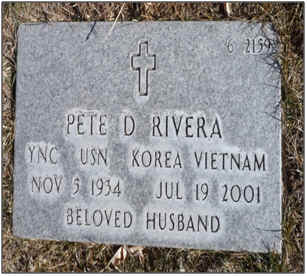

Another member of the de Ribera Clan Pete D. Rivera fought in both Korea and Vietnam. He served in the U.S. Navy.

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501

North Guadalupe Street Santa

Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA, PETE D

|

|

YNC

CPO U.S. NAVY

|

|

KOREA,

VIETNAM

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 11/05/1934

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 07/19/2001

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION 6 SITE 2159

|

Another of the de Ribera Clan who served in the Korea War was U.S. Army Private Gavino

J Rivera of Santa Fé,

New Mexico, born October

4, 1929 C.E. Rivera,

Gavino J, b. 10/04/1929, d. 08/17/1996, US Army, PVT,

Res: Albuquerque, NM, Plot: 9

0 2660, bur. 08/21/1996.

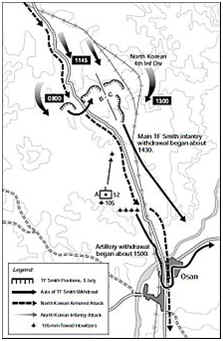

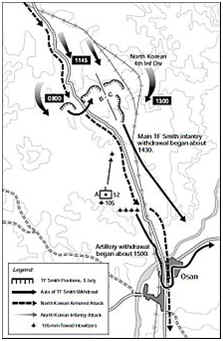

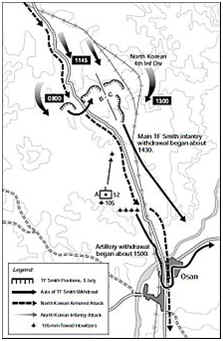

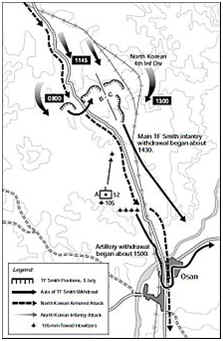

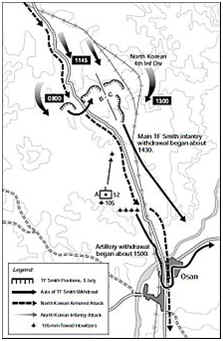

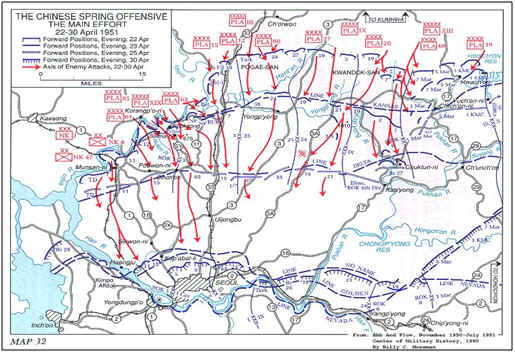

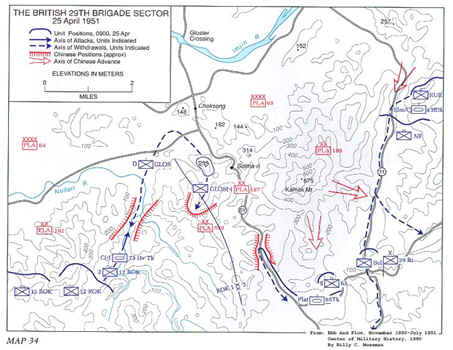

Corporal Eugene C. Rivera was another member of the de Ribera Clan from Santa Fé,

New Mexico, served in the Korea War. He was a Communications Chief and

U.S. Army Ranger serving with the 8th Ranger Company (Airborne) during

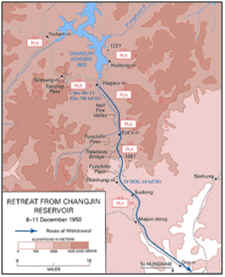

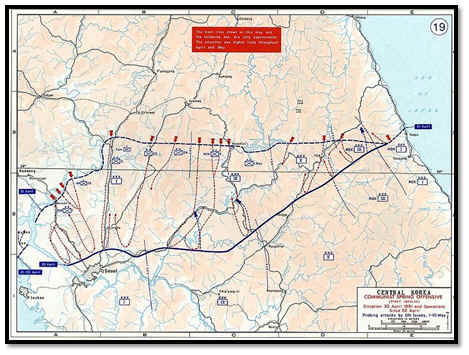

the Korean War. On April 25, 1951 C.E., the 8th Ranger Company found

itself heavily engaged with PAV forces as they provided forward

reconnaissance during the withdrawal of the U.S. 24th Infantry Division

near a Korean terrain feature designated Hill 628. Rivera

operating the only remaining radio adjusted artillery fire upon the

enemy. While doing so, the unit found itself trapped. Despite their best

efforts, friendly troops were unable to break through the Chinese lines

to reconnect with the isolated unit. As casualties mounted, the Rangers

were encouraged to, "Get out the best you can."

Not willing to abandon any soldier, the Rangers

prepared to make their final stand as CPL Rivera spotted American tanks. To save his fellow Rangers, CPL Rivera

of Santa Fé, New Mexico, bravely climbed a desolate hill, and while

under relentless fire from the enemy, established and maintained radio

contact with the U.S. Army tank platoon leader, Lieutenant David Teich.

Teich was in a tank company near the 38th parallel in 1951 when a radio

distress call came in from the Eighth Ranger Company. Wounded,

outnumbered, and under heavy fire, the Rangers were near Teich's tanks,

and facing 300,000 Communist troops, moving steadily toward their

position. Teich wanted to help, but was ordered to withdraw instead, his

captain saying "We've got orders to move out. Screw them. Let them

fight their own battles."

Teich went anyway and led four tanks over to

the Rangers' position. The tanks then took out so many Rangers on each

tank that they covered up the tank's turrets. Eugene C. Rivera’s selfless act allowed the M46 Patton, tiger-striped tanks

of the Sixth Tank Battalion to break the enemy encirclement and evacuate

the wounded.

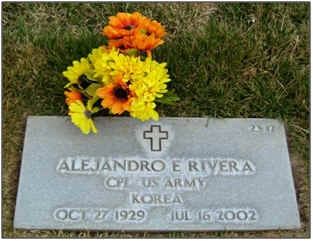

Following are more members of the de

Ribera Clan from New Mexico, that served during the Korea War in the

armed forces branches of the U.S. Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air

Force:

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501 North Guadalupe Street Santa Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA, ALEJANDRO E.

|

|

CPL

U.S. ARMY

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 10/27/1929

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 07/16/2002

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION 23 SITE 12

|

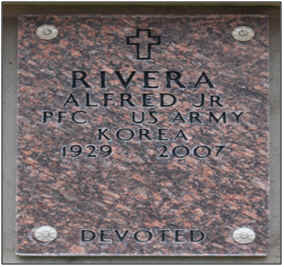

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501

North Guadalupe Street Santa

Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA, ALFRED JR

|

|

PFC

U.S. ARMY

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 02/07/1929

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 06/08/2007

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION COL-2 SITE A30

|

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501

North Guadalupe Street Santa

Fé, NM 87501

|

|

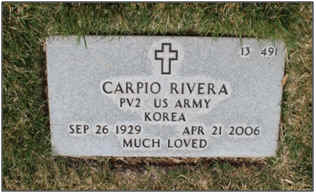

RIVERA, CARPIO

|

|

PV2

U.S. ARMY

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 09/26/1929

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 04/21/2006

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION 13 SITE 491

|

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501

North Guadalupe Street Santa

Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA, CLEMENTE GENOVEVO

|

|

PFC

U.S. ARMY

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 04/15/1931

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 02/04/2002

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION 3 SITE 678

|

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501

North Guadalupe Street Santa

Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA, FRANK AGUILINO

|

|

PV2

U.S. ARMY

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 06/04/1929

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 05/10/2007

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION V SITE 120

|

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501

North Guadalupe Street Santa

Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA, MANUEL R ABAN

|

|

U.S.

NAVY

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 11/08/1932

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 10/13/1996

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION V SITE 1231

|

|

SANTA FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501 North Guadalupe Street Santa Fé,

NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA,

ADOLFO JR

|

|

AB3 U.S. NAVY

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE OF BIRTH: 08/7/1930

|

|

DATE OF DEATH: 02/06/2014

|

|

BURIED AT: SECTION 24 SITE 875

|

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501 North Guadalupe Street Santa Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA,

LALO MARTOLO

|

|

SN U.S. NAVY

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE OF BIRTH: 10/12/1931

|

|

DATE OF DEATH: 05/03/2015

|

|

BURIED AT: SECTION 25B SITE 28

|

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501

North Guadalupe Street Santa

Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA, LUTHER L

|

|

SGT

U.S. MARINE CORPS

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 07/15/1931

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 08/09/2008

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION 19 SITE 55

|

|

SANTA

FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501

North Guadalupe Street Santa

Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA, RICARDO

|

|

A2C

U.S. AIR FORCE

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 03/11/1937

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 12/09/1979

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION 3 SITE 663

|

|

SANTA FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501 North Guadalupe Street Santa Fé, NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA,

BEN E

|

|

A1

U.S. AIR FORCE

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 10/26/1933

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 09/03/1985

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION 6 SITE 467

|

|

SANTA FE NATIONAL CEMETERY

|

|

501 North Guadalupe Street Santa Fé,

NM 87501

|

|

RIVERA,

JOSÉ ELOY (E.)

|

|

A3C

U.S. AIR FORCE

|

|

KOREA

|

|

DATE

OF BIRTH: 04/03/1934 Las Vegas, San Miguel County, New

Mexico, USA

|

|

DATE

OF DEATH: 05/06/2012

|

|

BURIED

AT: SECTION 24 SITE 688

|

The Hispano

Americans of New Mexico and other locales gave their all, and in some

cases, their lives during these wars. I often wonder what these men and

women would think of the 21st-Century C.E. if they were able to be

brought back to life. If they saw and heard this generation’s

questioning the need for patriotism and its mistrust of government and

its officials, and less than civil public discourse, would they be

confused or angered? Or would they agree?

I agree with President Theodore Roosevelt’s

statement when he said, “Patriotism means to stand by the country. It

does not mean to stand by the president or any other public official,

save exactly to the degree in which he himself stands by the country. It

is patriotic to support him insofar as he efficiently serves the

country. It is unpatriotic not to oppose him to the exact extent that by

inefficiency or otherwise he fails in his duty to stand by the country.

In either event, it is unpatriotic not to tell the truth, whether about

the president or anyone else.”

I.

Introduction

In this Chapter, I cannot hope do justice to

all of the men and women of all races and ethnicity who served in this

heroic effort. One would hope that others will attempt to write about

these other men and women. As this is the family history about a Hispano family, the de Riberas

of New Mexico, I have identified those fellow Hispanos from the state of New Mexico who were casualties of the

Korean War and placed their names and information in the months in which

they fell during the war.

As the de

Riberas are also Hispanic Americans, I chose to include other non-Hispano

Hispanic military personnel.

A.

The Power and Failure of the American Elite

The Korean War began when the ongoing civil war

escalated into open warfare. On June 25, 1950 C.E., Communist North

Korean People's Army (NKPA) forces supported by the Union of Soviet

Socialist Republics (USSR) and China invaded the Democratic south. This

was in an effort to unite the entire peninsula under one Communist

government. This was not about freedom.

The Korea Peninsula had been ruled by Japan

from 1910 C.E. until the closing days of World War II. The Union of

Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) then an Allied power declared war

on Japan in August 1945 C.E. After having reached an agreement with the

U.S., the USSR then liberated Korea north of the 38th parallel. By

liberation, I mean to say that the Soviets liberated all possessions

from all parties and controlled the means of any and all production.

It should have been understood by the American

Elite that by allowing, giving, providing

the USSR Communists a foothold anywhere on the Korean Peninsula

was to pretend that what they were doing in Eastern Europe of the time

was a one-off situation. Clearly history proved the Elites wrong! The

Communists had every intention of subverting any authority that was not

acceptable to them. Does the term “Comintern” strike a familiar

note!

The Comintern or Communist International was

an international Communist organization founded by Vladimir

Lenin the Russian communist revolutionary and head of the Bolshevik

Party. He rose to prominence during the Russian Revolution of 1917

C.E. The Comintern was established in Moscow, USSR in 1919 C.E. It

was officially dissolved in 1943 C.E.

This ultra-radical organization degenerated under Joséph

Stalin who served as General Secretary of the Central

Committee of the Communist Party USSR from 1922 C.E. to

his death on March 5, 1953 C.E. The Comintern became a political instrument of USSR

which was used to unite Communist groups in various countries. In

effect, the Comintern continued the promotion of Revolutionary Marxism,

including on the Korea Peninsula.

By 1948 C.E., U.S. forces moved into the Korean

south. The splitting of Korea into two separate governments was a

product of the Cold War between the USSR and the U.S. Both governments

claimed to be Korea’s legitimate government. Also, neither side

accepted the existing border as permanent.

Here it is important to clarify that before and

after the Korean War, the American elite or upper-class controlled and

directed U.S.’ foreign and domestic policy. Good or bad, every nation

on the face of the earth has its elite. The American elite or

upper-class thought itself to be as an aristocratic group, controlling

society's means of production. This included those who gain this

position due to socioeconomic means and not personal achievement.

The idea that the American cosmopolitan elite having

controlled and dominated American foreign policy and diplomacy is a

reality. Why is this important? It was this social stratum of American

society, and not the average man on the street, that assessed, planned,

and implemented the military engagements of the Korean War.

For the purpose of this chapter, the term,

"elite" describes a person or group of people who are members

of the uppermost class of society. In the U.S., this archaic society was

based upon lineage from parents or grandparents of the Revolutionary War

and passed-on. American elitists for a time were almost exclusively,

White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs). They were the social group

of wealthy and well-connected white Americans of Protestant and

predominantly British ancestry, many of whom trace their

ancestry to the American colonial period.

The American elitist’s belief and attitudes

about themselves was that they were a select group of people of a

superior ancestry, of intrinsic quality, of high intellect, wealth,

special skills, or experience. As such, they felt that they were more

likely to be more constructive for society as a whole. Therefore, they

deserved more influence and greater authority than the common working

man.

It was to the elites that the American people

of the 1940s C.E. and 1950 C.E. willingly left the all important

decisions of war. That includes the Korean War. I am not for one moment

saying that to enter the Korean Peninsula in the defense of its people

was unwise or unwarranted. What I am saying is that the elite

decision-makers failed to understand the entire scope of the conflict

before entering into that civil war. The American Elite’s strategic

military approach became one of changing plans in mid-stream which

eventually resulted in a tactical stalemate.

This elitist control would continue until at

least the 1960s. The group dominated American society and culture and

dominated in the leadership of the Republican and Democratic parties.

They were very well placed in major financial, business, legal, and

academic institutions and had close to a monopoly of elite society due

to intermarriage and nepotism.

During the latter half of the 20th-Century C.E.,

others of different ethnic and racial groups would grow in influence and

WASP dominance would begin to weaken. These Elites of the WASP American

families would remain as "the Establishment,” however, their

historical dominance and control over the financial, cultural, academic,

and legal institutions of the U.S. would gradually decline.

As opposed to the Elite, the average American

who had little power or control in the U.S., simply fought and died in

Korea for ideals. The ideals of "Freedom” and the “American

Dream” are the national ethos of the U.S. It’s a set of ideals in

which freedom includes the opportunity for prosperity, success, and an

upward social mobility for the family and children. At its base is that

belief that it is achieved through hard work in a society with few

barriers. About these good souls, I agree with Sargent Shriver’s

comments. “The only genuine elite are the elite of those men and women

who gave their lives to justice and charity.”

II.

Hispanic American Patriotism and the Korean War

Hispanics have fought in every American war

since the Revolutionary War. Many Hispanic Americans would again come

forward during the Korean War. They would give their all despite the

racial and ethnic prejudice existing in the nation which negatively

impacted them.

Hispanics and other minority groups did not

suffer from naïveté. They understood that the Native Americans

had been placed on reservations and that African Americans were

relegated to the edge society. Hispanics had seen Asian Americans

deported or placed in detention camps, or allowed work as gardeners and

cooks. The Hispanics also had been isolated into their barrios

where they forgot their historical and cultural roots. In short, to be

an American, meant to be perfectly American and Hispanics were clearly

not. During that time, under the best of circumstances every non-White

racial and ethnic group was tolerated. American society created a place

for each group which was not necessarily equal.

Now I return to the proposition that when and

where practicable, as Américanos,

these Hispanics were free to live as they wanted. Their innate belief in

America, its sense of “freedom” and the “American Dream” is what

drove them to readily participate in the many American wars. Their

adherence to those ideals led the de

Riberas to service America in Korea. This they did despite

America’s glaring faults.

Unfortunately after World War II ended, the

regular U.S. military had been considerably downsized. General

MacArthur's request for more troops was approved, but in order to meet

his needs quota, it became necessary to activate thousands of National

Guardsmen from all across the U.S. From then on, our nation's

National Guard played an important role in the Korean War.

According to the National Guard Bureau in

Arlington, Virginia, when war be out in Korea about one third (138,600

men) of the Army Guard's total strength was mobilized. Forty-three

units, including two infantry divisions, actually served in Korea. Other

guard units were deployed to stateside and worldwide locations close to

and far away from Korea.

There was more than National Guard manpower

needed. Some 67 percent of the Army National Guard's equipment was

also mobilized for war. The Army National Guard and the Air

National Guard gave up motor vehicles, tanks, and other ground weapons,

and light aircraft. This included 156 M-26 tanks and some 592 M-4

medium tanks. The Air National Guard provided its F-84 and F-74 jet

fighter aircraft, spare parts for these aircraft including the F-51

aircraft, life vests, and life rafts for the active forces.

Elements of the Air National Guard would also

be deployed. By the fall of 1950 C.E., about one sixth of the Air

National Guard would be activated. During 1951 C.E., 22 of the 27

Air National Guard wings, with supporting units, would be called up. These

Guardsmen left post-World War II civilian jobs, new brides, young

children, college studies, and many hopes and dreams when their units

were activated for the war.

In the American Southwest, the War Department

had earlier directed the reorganization of the New Mexico Guard in March

1947 C.E. This order gave the State five separate Anti-Aircraft

Battalions, one Operations Detachment, two Signal Radar Units, one

Engineer Searchlight Maintenance Unit, and three Ordnance Companies.

The Korean War caused activation into Federal

service of the 716th AAA Gun Battalion along with the 726th and 394th

Signal Radar Maintenance Unit. The 188th was also activated during the

conflict. New Mexico units furnished individual members, many Hispanos, as replacements to units engaged in active combat.

One group of American Hispanics that heard the

nation’s call and reported for duty was the

Puertorriqueños. Puerto

Rico’s 65th Infantry in an exercise involving the 65th in February

1950 C.E. changed the minds of many Army leaders about the 65th's

usefulness. The 65th held off the entire 3rd Infantry Division in a

successful defense. Pentagon planners took note. With the outbreak of

the Korean War in June 1950 C.E., the 65th was ordered to Korea and

assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division. Brigadier-General Juan

Codero, Puerto Rico's Adjutant General commanded the 296th Infantry when it

was mobilized in 1950 C.E. and was one of the commanders of the 65th in

Korea, making him, perhaps, the only Guard member to command a regular

regiment in Korea.

While the 65th was on its way, its sister Puerto

Rico Guard unit, the 296th Infantry, was mobilized. Like many Guard

units, the 296th was tasked to provide replacements. Brigadier-General Juan

Codero commanded the 296th Infantry when it was mobilized in 1950

C.E. and was one of the commanders of the 65th in Korea, making him,

perhaps, the only Guard member to command a regular regiment in Korea.

The 65th Infantry had always lived up to its

motto of "Honor and Fidelity."

It would fight in some of the toughest battles of the Korean War.

The Unit would earn two U.S. Presidential Unit Citations, two Republic

of Korea (ROK) Presidential Unit Citations, two U.S. Meritorious Unit

Commendations, and the Greek Gold Medal of Bravery. Four of its soldiers

would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest

award for valor.

Shortly after the 65th arrived in ROK, its

commander, Colonel William Harris, was approached by Eight Army

commander Lieutenant-General Walton Walker. The general asked,

"Will the Puertorriqueños fight?"

"I and my Puertorriqueños

will fight anybody," replied Harris proudly. Walker then pointed to

a waiting northbound train and ordered, "Get on, and then go that

way." For the next three years the men of the 65th would fight

their way up and down the Korean Peninsula.

Any doubts about their fighting ability would

be quickly dispelled. The regiment would earn a distinguished combat

record. Fighting in some of the toughest battles of the Korean War, the

65th would earn two U.S. Presidential Unit Citations, two Republic of

Korea Presidential Unit Citations, two U.S. Meritorious Unit

Commendations, and the Greek Gold Medal of Bravery. Four of its soldiers

would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest

award for valor.

Colonel Harry Micheli, later the senior Army instructor at the Antilles

Military Academy in Puerto Rico,

reported to the 65th as a new second lieutenant in the fall of 1951 C.E.

He stated, "I remember that the 65th was reorganizing after a year

of heavy combat. Many of the old-time regulars had left as casualties.

They were replaced by Puerto Rico Guardsmen, non-Hispanic Guardsmen from various states,

and The Republic of Korea Army (ROKA) replacements from ROK.

We trained until we were a cohesive unit," he added, "and then

we reentered combat."

III. A prelude to the Korean War - U.S. Political Events 1940-1950

C.E.:

A.

The World of WWII

I provide the following so that the reader

might have a better understanding of America and the world at large

prior to the Korean War. I start after the Europeans had begun WWII and

continue until the start of the Korean War. The world during this period

was an ugly, vicious, and cruel place. All nations involved suffered.

Why? WWII started because

the great European powers had unnecessarily forgotten the lessons of

WWI. Just four years before the Europeans repeated the errors of WWI in

1939 C.E, Winston Churchill gave a speech attempting to remind his

audience of past mistakes which led to War earlier.

In a 1935 C.E. House of Commons speech

after the Stresa Conference, Churchill suggested that failure to

act quickly in considering the future, not necessarily a failure to

adequately ruminate upon the past, will result in history repeating

itself. Churchill said, "Want of foresight,

unwillingness to act when action would be simple and effective, lack of

clear thinking, confusion of counsel until the emergency comes, until

self-preservation strikes its jarring gong — these are the features

which constitute the endless repetition of history.” WWII was a

result of that repetition of history.

By 1940 C.E., with Europe at war, everything

had changed. European countries were desperate for goods to use in the

war effort. They spent millions of dollars on American steel,

ammunition, weapons, and food. Yet private businesses were slow to react

to the demands of war. Many manufacturers continued to make consumer

goods when military hardware was most needed. Shortages of raw materials

also held up the recovery. Rather than issuing government orders or

taking control of industries, the Roosevelt administration chose to

guide private industry into producing what was required. It struck deals

with private businesses to boost wartime production. This mixture of

private money and federal incentives became the model for the American

economy for the next thirty years. Yet that same year, the federal

government estimated that more than half the families in the U.S. were

below the poverty level.

Between 1940 C.E. and 1945 C.E., American

industry would produce eighty-six thousand tanks, thirty thousand

aircraft, and sixty-five hundred ships. U.S. Steel would make twenty-one

million helmets for the army. Quality improved as well. Aircraft would

fly farther and faster than ever. The General-Purpose vehicle, known in

soldier slang as the GP, or Jeep, grew tougher. Advances were made

during wartime that helped American industry reach its dominant postwar

position.

Though these wartime production levels had

finally put an end to the Great Depression, in 1941 C.E., eight

million Americans remained out of work. Another eight million made less

than the legal minimum wage. Nearly 40% of America lived in poverty. The

median salary was less than 2,000 dollars per year. Despite all

government efforts to keep supplies steady, the war continued to create

shortages. In order to make sure essential supplies were shared fairly,

many items, including meat, sugar, butter, and canned goods were

rationed. Every U.S. citizen was given a book of stamps. These stamps

had to be handed over by the customer when he or she bought rationed

goods. Many suppliers made extra money by illegally selling rationed

goods to customers who did not have enough stamps, charging them extra.

Gasoline was also rationed, but in a different way. Every vehicle was

rated A to E, and carried a sticker in the window with a letter on it.

Those rated "A" were private automobiles, and were entitled to

very little gas. Emergency vehicles were rated "E," and could

take as much as they needed. Others fell in between. Before long, there

was a thriving black, or illegal, market in gasoline and other rationed

goods.

The 1940s C.E. would also witness a new regime

of Mexican expulsion or “Repatriation” from within the U.S. to

Mexico. Between 1941 C.E. and 1950 C.E., U.S. federal authorities would

deport more than 1.3 million Mexican nationals. Interestingly, this

included the time of WWII and the begining of the Korean War. By the

mid-1940s, continued annual arrests and expulsions of Mexicans illegally

present in the U.S. exceeded 60,000 per year. Did Hispanics understand

this was happening? The answer is, yes. Did they serve and fight in WWII

anyway? Again, the answer is, yes!

By 1943 C.E., the American economy was more

productive than it had ever been. Unfortunately, there were still

shortages at home.

Outside of the U.S., in some Latino

Américano countries the life of most inhabitants seemed little

changed in 1945 C.E., at the end of World War II, from what it had been

in 1910 C.E.

Latino

Américano economies remained hindered by backwardness. In

the Andean countries and Central

América, urban dwellers were a decided minority even at the end of

World War II, in 1945 C.E. Moreover, the usual pattern was that of a

single primate city vastly overshadowing lesser urban centers. Paraguay was still overwhelmingly rural and isolated, as was Honduras,

except for its coastal banana enclave. Even in Brasil,

the sertão, or semiarid

backcountry, was barely affected by changes in the coastal cities or in

the fast-growing industrial complex of São

Paulo. But in Latino América as

a whole more people were becoming linked to the national and world

economies, introduced to rudimentary public education, and

exposed to emerging mass media.

At the Yalta Conference in February

1945 C.E., Soviet leader Joséph Stalin pledged that his

nation would declare war on Japan exactly three months after Nazi

Germany was defeated.

By that time, Korea had been a Japanese

possession since the early-20th-Century C.E. During World War II,

the Allies, the U.S., USSR, China, and Great Britain (GB), made a

somewhat hazy agreement that Korea should become an independent country

following the WWII. As the war progressed, U.S. officials began to press

the USSR to enter the war against Japan.

The Korea of 1945 C.E. was still was a remote

country known only to a small number of missionaries and adventurous

businessmen. It held little importance in the official scheme of things.

Though the U.S. had proposed the thirty-eighth parallel as a dividing

line between the two occupation armies of the U.S. and the USSR, U.S.

policymakers still were unsure of the strategic value of ROK.

Formulating a U.S. policy for Korea was difficult due to the

intensification of the confrontation between the U.S. and the USSR and

the polarization of Korean politics between left and right. U.S. policy

toward Korea became even more uncertain after the deadlock of the

U.S.-USSR joint commission.

B.

The End of WWII

In Europe, German cities would be in need of

clean up and rebuilding. During the WWII, approximately 50 percent

of Nazi Germany's infrastructure was destroyed. Dresden was one of the

hardest hit cities. Eight square miles of Dresden, which had boasted

some of the most beautiful baroque architecture in Europe, were

destroyed when Allied bombers dropped more than 5,000 tons of high

explosives and incendiary bombs on the city in February 1945.

WWII was declared final or at its end on

victory in Europe Day on May 8, 1945 C.E. At this point the war in

the Pacific had not yet ended.

The Potsdam Conference (July 17, 1945 C.E.,-August

2, 1945 C.E.,) was held near Berlin. It was the last of the WWII

meetings held by the “Big Three” heads of state. Featuring U.S.

President Harry S. Truman, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (and

his successor, Clement Attlee) and Soviet Premier Joséph Stalin, the

talks established a Council of Foreign Ministers and a central Allied

Control Council for administration of Germany. The leaders arrived at

various agreements on the German economy, punishment for war criminals,

land boundaries, and war reparations. Although talks primarily centered

on postwar Europe, the Big Three also issued a declaration demanding

“unconditional surrender” from Japan. That unconditional surrender

would bring further complication. Korea was to become such a

complication. In the years before and during WWII, both the U.S. and

USSR had worked to liberate the region from the Japanese.

Also at the Potsdam

Conference it was agreed that USSR troops would occupy the northern

portion of Korea, as Japan was then occupying the Korean Peninsula. The

USSR was to invade the northern half of Korea and take it from under

Japanese control as agreed during the Potsdam Conference. The

American forces would liberate the southern half of Korea soon

thereafter. This was to be done in order to secure the area and

liberate it from Japanese control. The occupations were to be temporary,

and Korea was to eventually decide its own political future. Also, a

date was not set for the end of the U.S. and USSR occupations. Thus the

upcoming conflict in Korea would have its beginnings in 1945 C.E.

Early in August 1945 C.E., two young State

Department aides, Dean Rusk and Charles Bonesteel, consulted a National

Geographic map of Asia to determine the postwar dividing line

between USSR and U.S. zones of control in Korea. Neither was an

expert on the country. Failing to find any obvious natural barrier

between the North and the South, they selected the 38th parallel.

This new post-WWII border which would become the dividing line between

U.S. and USSR control zones in Korea had been tentatively proposed

after the Potsdam Conference. The division placed the capital city

of Seoul in the American zone, just 35 miles south of the dividing

line. On August 8, 1945 C.E., the USSR declared war on Japan. By August

9th, USSR forces invaded northern Korea. A few days later on August 14,

1945 C.E., the Empire of Japan surrendered.

The People's Republic of Korea (PRK),

a short-lived Korean provisional government was organized on

that same day of August 14, 1945 C.E. The Provisional Government of the

Republic of Korea was a partially recognized Korean

government-in-exile, based in Shanghai, China, and later in Chungking,

during the Japanese Korean period of 1910 C.E. through 1945 C.E. On

April 11, 1919 C.E., the provisional constitution was enacted, and the

national sovereignty was called "Republic of Korea (KPG)" and

the political system was called "Democratic Republic." It

introduced the presidential system and established three separate

systems of legislative, administrative and judicial separation. The KPG

claimed that it inherited the territory of the former Korean

Empire. It actively began supporting an independence movement under the

Provisional Government. KPG received economic and military support from

the Kuomintang of China, the USSR, and France.

The Provisional Government resisted Japanese

colonial rule of Korea and coordinated the armed resistance against the

Japanese Imperial Army during the 1920s C.E. and 1930s C.E. This

struggle culminated in the formation of Korean Liberation Army in

1940 C.E., which brought together many if not all Korean resistance

groups in exile. With the liberation of Korea from Japanese

occupation at the end of World War II, the Korean Provisional Government

came to an end.

After the Surrender of Japan on

August 15, 1945 C.E., the Provisional Government of the KPG was

dissolved. Its members then returned to Korea, where they began to put

together their own political organizations in what came to be South

Korea and competed for power. On August 15, 1948 C.E., Syngman Rhee a

Korean a politician in the south, became the first president of the

Provisional Government of the KPG. The Constitution of South Korea

stated that the Korean people inherited the rule of the KPG.

C.

Post WWII World

1.0

The USSR Enters the Korean Peninsula

On August 18, 1945 C.E., several USSR

amphibious military landings were conducted ahead of the land campaign.

The three landings took place in northern Korea. One landing was

at South Sakhalin. A second landing took place in the Kuril

Islands, in preparation for USSR 25th Army troops coming overland. The

third landing was in South Sakhalin and the Kurils, located directly to

the north of Japan and east of Sakhalin. The purpose was

the establishment of USSR sovereignty. Next, the USSR military land

advance was stopped a good distance short of the Yalu River. There

the Korean Peninsula starts.

Over the next few years, the situation in Korea

would steadily worsen. A civil war between communist and nationalist

forces in southern Korea would result in thousands of people killed and

wounded. With forces in Korea, the USSR was able to establish control in

the Peninsula's northern area and immediately establish a headquartered

at P’yŏngyang for a period. In accordance with

arrangements made earlier with the American government to divide the

Korean Peninsula, USSR forces stopped at the 38th parallel, leaving the

Japanese still in control of the southern part of the Peninsula. They

had agreed to temporarily to divide Korea at the 38th parallel of

latitude north of the equator.

The USSR would continue in its steadfast

refusal to consider any plans for the reunification of Korea. This

policy division would eventually result in the formation of two

countries. In the north, above the 38th parallel was communist Korea

under the leadership of Kim Il-Sung supported by the Soviets. To the

south was to be a democratic Korea headed by Syngman Rhee supported by

the U.S. Like the American forces in the south, USSR troops remained in

Korea after the end of the war to rebuild the country. The Soviets were

also instrumental in the creation and early development of the NKPA and Korean

People's Air Force (KPAF), as well as for stabilizing the early years of

the Northern regime.

Japan formally signed surrender documents

on September 2, 1945 C.E., WWII was formally at an end. That same month,

in North Korea the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) was

established. Korean leaders and exiles abroad, mainly in China, had

earlier established self-governing bodies, or people's committees, and

organized the Central People's Committee. These exiles had sustained a

skeletal organization in other parts of China until 1945 C.E., awaiting

their return to Korea. These proclaimed the establishment of the

"Korean People's Republic" on September 6, 1945 C.E.

2.0

The U.S. Enters the Korean Peninsula

On September 7, 1945 C.E., U.S. General Douglas

MacArthur announced that Lieutenant-General John R. Hodge was

to administer South Korean affairs. Keeping to their part of the

bargain, U.S. forces entered southern Korea under Lieutenant-General

Hodge and landed in Inch’ŏn the following day of

September 8, 1945 C.E., the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK)

was established as the official ruling body of the southern half of the Korean

Peninsula. With this in place, U.S. troops in Korea began their postwar

occupation.

The Lieutenant-General, commander of the U.S.

occupation forces in Korea would be obliged to work under a severe

handicap. His mission was to maintain peace and order until the

international conflict over Korea was resolved. His administration

possessed very limited resources, yet Hodge was expected to pursue the

"ultimate objective" of fostering conditions which would bring

about the establishment of a free and independent nation. In addition,

Lieutenant-General Hodge had to contend with hostile Korean political

groups.

The months after Hodge’s arrival, he would

witness a vast inflow of population. South Korea's population, estimated

at just over 16 million in 1945 C.E., would grow by 21 percent during

the following year.

The Provisional Government of the Republic

of Korea, sent a delegation with three interpreters to General Hodge,

but he refused to meet with them. The U.S. recognized neither the

republic nor the provisional government headed by Syngman Rhee, its

first president, and Kim Ku and Kim Kyu-sik, premier, and vice premier,

respectively. The U.S. would not recognize any group as a government

until an agreement was reached among the Western Allies. The exiles were

appeased by the favorable treatment they received when they returned to

South Korea, however, they were now incensed by the U.S. Military

Government in Korea's order to disband. The U.S. Army military

government that administered the American-occupied zone proceeded to

disband the local people's committees and impose direct rule, assigning

military personnel who lacked language skills and knowledge of Korea as

governors at various levels.

On September 12, 1945 C.E., the People's

Republic of Korea (PRK) was again proclaimed, as Korea was being

divided into two occupation zones, with the USSR occupying the north,

and the U.S. occupying the south. In the north, the Soviet authorities

co-opted the committees into the structure of the emerging DPRK (North

Korea). It was based on a network of people's committees and

presented a program of radical social change.

Although the U.S. and USSR occupations were

supposed to be temporary, the division of Korea quickly became

permanent. At this juncture, each side was willing to make

accommodations.

3.0

Ratification of the United Nations

In the world at large, the United Nations (UN)

Charter was ratified by its five permanent members the U.S., GB, France,

China (the non-Communist Republic of China), and the USSR on October 24,

1945 C.E. It was to become the international stage for resolving

disputes peacefully.

The Korean Communist Party was resuscitated in

October 1945 C.E. with the help of the Comintern. It had been a major

force behind the Central People's Committee and the "Korean

People's Republic." It quickly built a substantial following among

the workers, farmers, and students.

On November 13, 1945 C.E., the Free French

leader General Charles de Gaulle was named president of France's

Provisional Government of the French Republic (1944 C.E.-1946 C.E.).

With WWII over, France was ready to rebuild.

On November 20, 1945 C.E., the Nuremberg Trials

opened. For the next 10 months, a tribunal comprised of Allied jurists

would pass judgment on scores of Nazi war criminals.

4.0

The Moscow Conference and the Division of Korea

The decision for the final division of Korea

would be made at the Moscow Conference in December of 1945 C.E., between

the U.S., the USSR, GB, and the Republic of China. At that time, the Republic

of China was a sovereign state in East Asia founded in

1912 C.E., after the Qing dynasty, the last imperial dynasty, was

overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution. It occupied part of

territories within modern China, Mongolia, and Taiwan.

These parties would have Korea ruled over by a

trusteeship for five years starting in 1946 C.E. The eventual goal was

to be an entirely independent Korea.

The Americans selected the 38th Parallel

for the dividing of Korea when the onslaught of the USSR

offensives in Asia threatened to turn the whole peninsula of Korea into

a Communist state. It was believed that the USSR would attempt to take

the entire Korea Peninsula forcing the U.S. to leverage the fact that it

had fought for most in the Pacific and therefore deserved rights to the

entirety of Korea. This was the same argument the Soviets used with

Eastern Europe. The Soviets accepted this remedy. Why were the Soviets

so accepting of half of Korea rather than its entirety? It allowed the

Soviets to have a Communist partner in Asia. It should be remembered

that the Soviets to have even half a Communist country in Asia, was

better than having nothing at all. At that time, the Soviets were still

awaiting the outcome of the Chinese Civil War and Vietnam remained a

French colony. The USSR would later try to gain the entirety of Korea

through its backing of Kim il-Sung and the Korean War.

In international affairs, the U.S. government

committed to a multibillion-dollar loan to prop up the British economy

on December 6, 1945 C.E. U.S. President Truman ended the wartime Lend

Lease arrangements abruptly in August 1945 C.E. Suddenly, GB found it

did not have enough dollars to make expected payment for undelivered

supplies, bankruptcy loomed. As GB emergency measure, the government

sold gold and minerals, this GB could not do for long. GB attempted

negotiations on the matter expecting a gift in recognition of the

country's contribution to the war effort. Despite three months of hard

wrangling, the Anglo American Agreement produced a business loan instead

of a subsidy, with additional conditions in America’s favor. In

December 1945 C.E., the British Government succumbed, agreeing to not

only a U.S. loan of $4.34 billion, then double the size of the then

British economy, but also other onerous stipulations.

GB’s economy had been distorted by six years

of total war. GB had given her all for the freedom of the world. Both

blood and treasure had been expended in great amounts. During the war,

the British economy had been heavily geared towards war production, at

approximately 55 percent of her GDP. This was much greater than in the

USSR or America. The wartime U.S. Lend Lease arrangements started in

1941 C.E. had helped GB through her wartime difficulties. GB was now in

a precarious position. She was exporting only approximately a fifth of

what it had before the war and non-military imports were five times

higher than in 1938 C.E. 1.4 million people would remain in the armed

forces by 1946 C.E.

Meanwhile in Korea’s south, the U.S. military

government under Lieutenant-General John R. Hodge, administrator

of Korean affairs, refused to recognize the newly formed People's

Republic of Korea (PRK) and its People's Committees, and outlawed

it on December 12, 1945.

By December 17, 1945 C.E., at the Moscow

Conference, the Allies agreed that the U.S., the USSR, the Republic of

China, and GB would take part in a trusteeship over Korea. It

was to be for up to five years in the lead-up to independence. The Council

of Foreign Ministers agreed on Korea having a provisional

government, or temporary government, set up quickly before a real

government was ready. This would become difficult to do because of the

growing Cold War. Though the U.S. officials were pessimistic about

resolving their differences with the USSR, they remained committed to

the December 1945 C.E. decision of the Allied foreign ministers (made

during their Moscow meeting) that a trusteeship under four powers,

including China, should be established with a view toward Korea's

eventual independence. Thus, U.S. officials were slow to draw up

long-range alternative plans for South Korea.

Moreover, as the USSR consolidated its power in

North Korea and the Nationalist Party (Guomindang or Kuomintang--KMT)

government of Chiang Kai-shek began to falter in China, Theses and other

issues caused U.S. strategists to begin to question the long-run

defensibility of South Korea.

When the decision

to establish a five-year trusteeship in Korea was announced, it

exacerbated an already difficult situation. To the Koreans, many who had

anticipated immediate independence were humiliated. The initially warm

Korean welcome to U.S. troops as liberators cooled. Many Koreans began

demanding their independence immediately. The Korean Communist

Party, which was closely aligned with the USSR Communist party,

supported the trusteeship. Why? They believed that they could later take

by force what they wanted.

In the U.S. after 1945 C.E., America’s major

corporations began growing larger. With the pressure of growth,

corporate America was desperate to separate Americans from the $140

billion they had saved in times of shortage and rationing. Keeping that

spending under control would be one of the biggest challenges faced by

U.S. President Truman in the late-1940s C.E.

The automobile

industry was robust. The number of automobiles produced annually would

quadruple between 1946 C.E. and 1955 C.E. At the same time, a housing

boom was being stimulated in part by easily affordable mortgages for

returning servicemen. This also would fuel the expansion. The rise in

defense spending as the Cold War escalated would play a part in economic

growth.

Workers found their own lives changing as

industrial America changed. Fewer workers produced goods; more provided

services. Within the U.S., economic growth was being driven by different

sources. By 1946 C.E., unemployment was low, wages were at record

levels, and the economy was booming. Labor shortages caused by the war

meant that many women and teenagers had entered the labor market. Soon,

the returning soldiers would threaten to push unemployment back up after

the war. To mitigate this, U.S. President Truman, Roosevelt's successor,

used the GI Bill to put the soldiers through college instead.

This eased the pressure on the economy and produced a better-educated

workforce.

Also in 1946 C.E., the U.S. government

closed the internment camps in which some 120,000 ethnic Japanese in the

American West had been incarcerated since 1942 C.E. This issue continues

to haunt the U.S. even unto our day.

In Europe, after end of WWII, in 1946 C.E., the

eight square miles of Dresden ruins would be cleared and replaced by

modern structures. The Dresden Frauenkirche, a Lutheran church, was

an exception, as its decaying ruins were left untouched. After the

reunification of Germany, the church was restored for $175 million.

Homeless German children bartered and begged. Young

children sold or bartered whatever they could to survive on the streets

of Berlin. A black market developed in Berlin, with cigarettes, liquor,

and chocolate as three of the commodities most sought by Berliners from

occupation troops. For many months after the war, German children would

roam the streets scavenging or beg for food.

Regarding Asia, by early 1946 C.E. the USAMGIK

responsible for the governance of the south had come to rely heavily on

the advice and counsel of ideologically conservative elements within

Korea. These included landlords and other propertied persons.

A Joint USSR-U.S. Commission met in 1946 C.E.

and later in 1947 C.E. to work towards a unified Korea administration.

Unsurprisingly, it failed to make progress. This was due to increasing Cold

War antagonism and to Korean opposition to the trusteeship. Meanwhile,

the division between the two zones was deepening as the difference in

policy between the occupying powers led to a polarization of politics.

It was also to be the genesis of the future transfer of population

between North and South.

By 1947 C.E., these divisions in Korea were

causing social unrest. Only approximately half the Korean labor force of

10 million was gainfully employed. Labor strikes and work stoppages were

occurring. Demonstrations orchestrated by the communists against

USAMGIK's policies drew large crowds. Temporary stoppages of

electricity--supplied from the northern areas--in the early part of 1946

C.E. and later in late-1947 C.E., plunged the southern region of Korea

into darkness on both occasions. Also the economic situation was at this

point nearly as difficult in the north as it was in the south. During

Japanese occupation of the peninsula they had concentrated agriculture

in the south and heavy industry in the north. A complete transition of

the existing infrastructure was needed. There was a deepening despair

affecting the Korean people and they were becoming disillusioned and

disconcerted. Koreans began to pay close attention to political leaders

of various persuasions who offered new ways of solving the Korean

problem.

In Japan, on January 1, 1946 C.E., Emperor

Hirohito addressed his subjects and stated that he was not, contrary to

popular belief, a divine being. This proposition was unfathomable for

most Japanese to accept.

The Korean Communist Party had been taking

various stances on the idea of trusteeship. It once again changed its

stance on trusteeship and came out in support of it on January 3, 1946

C.E. The Party remained under the control of the USSR command in P’yŏngyang.

Should it be necessary for the Party to come into disagreement later, it

could be used to come into direct confrontation with the U.S. military

government.

On the world stage, on January 17, 1946 C.E., the

UN Security Council (UNSC) convened in London to agree on procedural

rules for the international body. A week later, on January 24, 1946 C.E., the

International Atomic Energy Commission was established to help regulate

emerging nuclear weapons technology.

In North Korea, in February 1946 C.E., a provisional

government called the Provisional People's Committee was formed

under Kim Il-sung Kim Il-sung (April 15, 1912-July 8, 1994). He had

spent the last years of WWII training with Soviet troops in Manchuria.

Conflicts and power struggles would later ensue at the top levels of

government in P’yŏngyang as different political aspirants

maneuvered to gain positions of power in the new government.

By March 1946 C.E., the Provisional People's

Committee instituted a sweeping land-reform program. Lands belonging to

Japanese and collaborator landowners was divided and redistributed to

poor farmers. The Communists next organized the many poor civilians and

agricultural laborers under the People's Committees. Soon, a nationwide

mass campaign began to control the old landed classes. Landlords were

allowed to keep only the same amount of land as poor civilians who had

once rented their land, thereby making for a far more equal distribution

of land. As a result, former village leaders were eliminated as a

political force without resort to bloodshed, precluding their return to

power. The new landowning farmers responded positively. This North

Korean land reform was achieved with little violence. Also, northern

Korean key industries were nationalized.

Many of the Japanese, collaborators, and former

landowners in the north fled to the south. The U.S. military government

estimated that 400,000 northern Koreans moved to the south as refugees.

There some of them obtained positions in the new South Korean

government.

In another part of Asia, on March 2, 1946 C.E., the

Communist revolutionary nationalist leader Hồ Chí Minh (May

19, 1890 C.E.-September 2, 1969 C.E.) became the Chairman and

First Secretary of the Workers' Party of Vietnam. Earlier,

following the August Revolution (1945 C.E.) organized by the

Việt Minh, Hồ Chí Minh had become Chairman of the

Provisional Government.

He was also President (1945 C.E.-1969 C.E.)

of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam). He was a key

figure in the foundation of the People's Army of Vietnam.

The intensification of the confrontation

between the U.S. and the USSR had only continued to worsen. The

Capitalist Western Bloc (the U.S, its allies, and others) now

understood the challenge being presented by the Communist Eastern Bloc

(the USSR, its satellite states, and the communists in China).

On March 5, 1946 C.E., former British Prime Minister Winston

Churchill delivered his seminal "Iron Curtain" speech at

Missouri's Westminster College. It is considered one of the most famous

orations of the Cold War period. Churchill condemned the USSR’s

policies in Europe and declared, “From Stettin in the Baltic to

Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has

descended across the continent.” This Churchill speech is

considered one of the opening volleys announcing the beginning of the

Cold War.

Frustrated by Japan's lack of progress with

creating a new constitution, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur assigned the

role to members of his own staff. The result was a constitution based

more on British parliamentary rule than on the U.S. model. The document

limited the “human” Emperor of Japan to a symbolic role. It also

gave women the right to vote. Women reacted enthusiastically. In April

1946 C.E., for the first time in their nation's history millions of

Japanese women voted in the election that gave Japan its first modern

prime minister, Yoshida Shigeru. Japanese women vote in Japanese

election. When Japan’s women cast their votes, it was perhaps the

most visible sign of Japan's postwar political transformation to the

modern age.

On April 28, 1946 C.E., the Allied

International Military Tribunal for the Far East indicted Japanese war

minister Tojo Hideki as a war criminal. It charged him with 55 counts.

He would later be sentenced to death in November 1948 C.E.

In May 1946, it was made illegal to cross

Korea’s 38th parallel without a permit. Both sides were

consolidating control of their borders. Also, in May of 1946 C.E. and

later, in April 1947 C.E., the U.S. supported the returned Korean exiles

and the conservative elements. To facilitate this, the U.S. military

government tried to mobilize support behind a coalition between the

moderate left represented by Yo Un-hyong, who had been the figurehead of

the Central People's Committee, and the moderate right, represented by

Kim Kyu-sik, vice premier of the exiled government.

During the movement to unify Korea’s

political left and the political right, Lyuh Woon-hyung represented the

center-left. Specifically, he occupied a position on the center between

the left and the right. Lyuh’s political stance was attacked by both

the extreme right and the extreme left. This made his efforts to pursue

a centrist position increasingly untenable by the political realities of

the time. As for Kim Kyu-sik of the right-wing group, this leader had

been the clear choice of the U.S. military government. He, however,

could not be dissuaded from his fruitless trip to P’yŏngyang in

the north, leaving in place a political standoff. These attempts only

intensified the existing splits within the left-wing and right-wing

camps. It produced no positive results.

During that month, there were many other

problems facing the U.S. South Korean left-wing and right-wing groups

frequently engaged in violent clashes and not only on ideological

grounds, but also because of their opposing views about the trusteeship

decision. The moderates took the position that Koreans should oppose the

trusteeship. This was unacceptable to the other parties. Communist

leaders were driven underground in May 1946 C.E. after the discovery of

a currency counterfeiting operation run by the Party.

By June 1946 C.E., the ardent anti-communist Syngman

Rhee wanted the immediate independence of Korea, even at the price of

indefinite division. He campaigned actively for this within Korea and

the U.S.

In the U.S. of the postwar years, the consumer

age had begun. Americans were buying huge numbers of cars,

refrigerators, televisions, and other household appliances. Price

controls imposed by the Office of Price Administration (OPA)

ended on July 1, 1946 C.E. Almost immediately, prices increased. This

time, American industry was ready to respond. It increased production of

consumer goods forcing prices back down.

Also on July 1, 1946 C.E., on the military

front the U.S. detonated a plutonium bomb "Able," off Bikini

Atoll. It was a part of Operation Crossroads, an effort to learn more

about the power of the atomic bomb. The U.S. postwar nuclear tests at

Bikini Atoll were designed to examine the effects of atomic bombs on

naval vessels. Bikini's 167 inhabitants had been forcibly relocated in

early-1946 C.E., and 71 surplus and captured ships were anchored in the

lagoon to serve as targets. Other targets included planes and 5,400

rats, goats, and pigs.

In Europe, a little after a years of the

War’s end, on July 4, 1946 C.E., a false kidnapping allegation fueled

an anti-Semitic pogrom in Kielce, Poland, claimed the lives of some 40

Jews. It is only fitting that their fellow travelers, forty-three

members of the Waffen-SS, were sentenced to death on July 16, 1946

C.E. for the December 1944 C.E. Malmedy Massacre of American

prisoners-of-war (POWs) during the Battle of the Bulge. They would

eventually be released.

In Korea, on July 19, 1947 C.E., Lyuh

Woon-hyung who represented Korea’s political center-left,

specifically, a position on the center between the left and the right,

was assassinated in Seoul by a 19-year-old man named Han Chigeun. The

19-year-old was a recent refugee from North Korea and an active member

of a nationalist right-wing group. There is no question in my mind that

the Communists orchestrated that foul act.

On July 25, 1946 C.E., a second U.S. nuclear

detonation, code-named "Baker," took place. The two separate

atomic blasts sank ships and left others heavily contaminated with

radiation. Whatever the scientific gains, the highly public tests only

exacerbated deteriorating relations between the U.S. and the USSR.

In September 1946 C.E., thousands of

Korean laborers and peasants rose up against the USAMGIK, but the

uprising was quickly quelled. Much to the communists’ chagrin it

failed to prevent scheduled October elections for the South Korean

Interim Legislative Assembly. Also that month, the ardent anti-communist Syngman

Rhee, and first president of the Provisional Government became the most

prominent politician in the South. He would later work as a pro-Korean

lobbyist in the U.S. pressuring the American government to abandon

negotiations for a trusteeship and create an independent Republic of

Korea in the south.

The communists in South Korea participated in

another serious riot in October 1946 C.E. Soon, most of their leaders

left for the north. Again, their attempt to stop the October elections

for the South Korean Interim Legislative Assembly failed.

In Europe, on October 1, 1946 C.E., high-ranking

Nazi officials, including Hermann Göring, Hans Frank, Joachim von

Ribbentrop, and Arthur Seyss-Inquart, were sentenced to hang by the

Allied court at Nuremberg. The Nazis were being given their well earned

rewards for the holocaust.

Only Göring would escape his fate by the

taking of his own life shortly before his scheduled execution.

November 3, 1946 C.E., a new Japanese

constitution, one that resolves that the nation will never again

"be visited with the horrors of war through the action of

government," was proclaimed by Emperor Hirohito. He was the very

person responsible for that horrible war in the Pacific and in Asia.

In December 1946 C.E., the USAMGIK established

the South Korean Interim Legislative Assembly. It was to formulate draft

laws which would be used as the basis for political, economic, and

social reforms. South Korea's substantial problems, however, required

solutions at a much higher level. Earlier during the Korean-Japanese

Period, Japan had developed Korea's economy as an integral part of their

empire, linking Korea to Japan and Manchuria. Even if the U.S. Military

occupation forces had arrived with a carefully developed economic plan,

the situation would have still been difficult. The division of the two

Koreas into two zones at an arbitrary line further aggravated the

situation. These and many other inherent problems in the building of a

self-sufficient economy in the southern half of the peninsula imposed a

great burden.

Most of the heavy industrial facilities were

located in northern Korea, in the USSR zone. These included the chemical

plants that produced necessary agricultural fertilizers. Southern

Korea’s light industries were dependent on electricity from the

hydraulic generators located on the Yalu River on the Korean-Manchurian

border. Electric generating facilities in the south supplied only 9

percent of the total need. Railroads and industries in the south also