|

Chapter

Nine

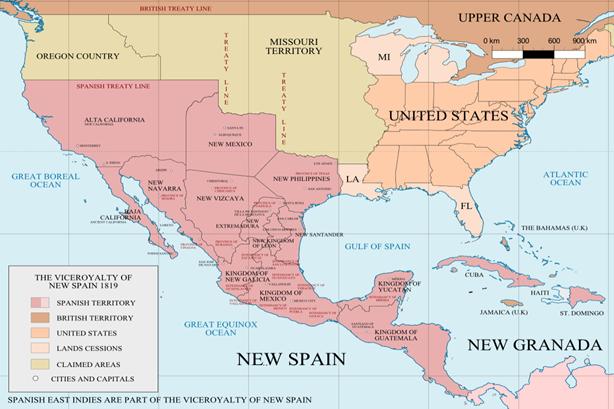

Nuevo Méjico after the Españoles From

the de Córdoba Expedition to the Don

Juan Pérez de Oñate y Salazar Juan de Oñate Expedition Our

thanks again to all the sources available on the Internet

The

area of Nuevo Méjico

or New Mexico in today’s United States of America became the

historical homeland of my progenitors, the de

Riberas, from 1598 C.E. onward. The

family members were subjects of the Imperio

Español or Spanish Empire. The

assumption here is that the reader understands the implications of that

statement. España

was to become el Imperio

Español. This is to say

that she was under a single supreme authority the Catholic Monarchs the

joint title used in history for Queen Ysabel

I de

Castilla

y León

and King Fernando

II de Aragón.

They were both from the

House of Trastámara a dynasty of

kings in the Iberian Peninsula which first governed in Castilla beginning in 1369 C.E., before

expanding its rule into Aragón,

Navarra and Naples. It

would continue to grow into an extensive group of states or countries. Just

as the “Roman Empire” had begun small and became large, so did el

Imperio Español. It

would encompass kingdoms, realms, domains, and territories by whatever

means necessary including war. This

would include acquisitions of other European states in the

Viejo

Mundo or Old World and the

exploration, annexation, and conquest of entities in the New World or Nuevo Mundo. During his first voyage in 1492 C.E., Cristóbal Colón or Christopher

Columbus reached the Nuevo

Mundo landing on the island in the Bahamas archipelago that Columbus named "San

Salvador," instead of arriving in Japan as he had intended. Over

the course of Columbus’ last three voyages he visited the Greater and Lesser Antilles or Antillas, as well as

the Caribbean coast of Venezuela

and Central America. He

claimed it all for the Crown of Castilla.

Later other Españoles would explore areas of the Nuevo

Mundo. After

being charged with various crimes while under his governorship of the Nuevo

Mundo, Columbus and his brothers were arrested and imprisoned upon their

return to Spain from the third voyage.

They lingered in jail for six weeks before busy King Ferdinand

ordered their release. Not

long after, the king and queen summoned Columbus

and his brothers to the Alhambra

palace in Granada.

There the royal couple heard the brothers' pleas; restored their

freedom and wealth; and, after much persuasion, agreed to fund Columbus' fourth voyage. However,

the door to Columbus' role as

governor was firmly closed and in the end he didn’t receive what was

agreed upon. This would

become a pattern for great men doing great deeds for the Crown.

Their great deeds were only remembered for a short time.

These men would fall from grace, losing all they had worked and

suffered for. Their

positions and power would soon be given to the favorites of the Crown. 1517

C.E.

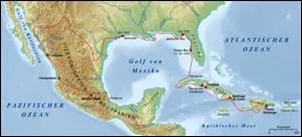

The Francisco Hernández de Córdoba Expedition In

1517 C.E., conquistador Francisco Hernández

de Córdoba had led an expedition of three ships and a small army of

approximately 110 soldiers. He

had petitioned the Gobernador

of

Cuba, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar

(1465 C.E. in Cuéllar, España-ca. June 12, 1524 C.E.

in Santiago de Cuba),

to lead an expedition to look for new lands and slaves.

This first documented Spanish exploration of the mainland west of

the Antillas

led

by three Cuban pobladores, de Córdoba

was one of the three. It

also included two other leaders of the expedition López

Ochoa

Cayzedo, and Cristóbal Morantes. De

Córdoba

sailed west in three ships (naos or caravels) on February

8, 1517 C.E. with Capitán

Fernando

Iñiguez

and the pilot Antón

de

Alaminos (Palos de la Frontera, 1482 C.E.-1520

C.E.)

Departing from Santiago de

Cuba, they passed Cabo San

Antonio at the westernmost tip of Cuba

12 days later. They would

soon cross the 66 leagues (about 200 miles) of the Yucatán

Channel in nine days. By March 4, 1517 C.E., after surviving a fierce a two day storm, they

sighted the coast of the Yucatán

and Mayan stone buildings. The

Córdoba Expedition had

discovered a large, well-built city, the first true city the Españoles had

yet encountered in the Americas. They

soon made landfall probably at Isla

Mujeres near Cabo Catoche.

There Bernal

Díaz del Castillo and Pedro

Mártir de Anglería or Martyr

describe idols of goddesses named Aixchel

and Ixhunié ("ix" being Yucatec

for "woman"). Fray

Diego de Landa Calderón

(November 12, 1524 C.E.-April

29, 1579 C.E.)

reports they saw a "building of stone, such as to astonish them;

and they found certain objects of gold which they took." With

them was also the sailor, Blas

Hernández. Later,

excited by the great potential of this discovery, Los Españoles

sent

messengers to the local Maya.

Fatefully, the Spaniards understood the Mayas'

sign language as greetings and invitations to enter the city and landed

on the shore expecting hospitality.

Unfortunately for them, the shipwrecked Spanish sailor Gonzalo

Guerrero awaited the party. Notes: In 1511

C.E., a ship containing several hundred Spaniards sailing north from

an early colony started by Columbus

at Panama on its way to Santo

Domingo foundered off the northern coast of the Yucatán

Peninsula at Cabo Catoche

or Cape Catoche. Most

of the Spaniards who made it to shore were captured by the local Maya

and later sacrificed. 15 men

managed to escape in a lifeboat. The

local cacique

spared only a handful to remain as slaves, all but

two men, Gonzalo Guerrero and Gerónimo

de Aguilar who had washed ashore managed to survive being

sacrificed or worked to death in slavery by the Mayans. Gonzalo Guerrero became as slave, but earned his freedom after

proving himself in battle. He

learned Mayan and married a Mayan princess, Zazil

Há and had three children. He

tattooed his face and pierced his ears in the fashion of the Mayans.

He became a Mayan chief (Cacique) mayor of the Mayan town of Chetumal. While Aguilar

remained rigidly loyal to his king and religion, Guerrero

had a profound change of heart. He

offered his services as a warrior and tactician to the local cacique. After

living among the Maya, he had

turned against the Españoles and

convinced the Natives to attack them on

sight. The Maya

ambushed the Españoles,

who had to fight their way back to their ships, but by then the conquistadores

had seen enough gold in the town and on their adversaries to excite

their greed. They

then explored the waters off the Yucatán

Peninsula

and landed near the town of Champotón,

losing many Españoles

killed in battle. The party

returned to Cuba, where de Córdoba died of his wounds.

The Expedition proved that there were vast lands to the west,

populated by natives, and possibly held much treasure. It was the early explorations in the Caribbean like that

of de Córdoba that would establish important precedents for exploration,

conquest, settlement, and crown rule by the Monarchs.

The mechanisms of governance which had been instituted would have

lasting effects upon subsequent regions. However

at that time, the Caribbean islands and areas around the Caribbean

region were not of major importance to España

politically, strategically, or financially until the conquest and

annexation of the Azteca

Empire in 1521 C.E. The many

different and varied indigenous societies of Mesoamerica which would

eventually be brought under control of España such as Méjico and Peru would be of

unprecedented complexity and wealth. These newly controlled indigenous cultures represented

important opportunities and potential threats to the power of the Crown

of Castilla. The

complexity of arrangements with the conquerors and the wealth which was

being obtained allowed them to act independently of the effective

control of the Crown. These

societies could provide Hernán

Cortés and the other conquistadors

with bases from which they could become autonomous and independent of

the Crown. In relation to

this issue, by 1524 C.E., the

Holy Roman Emperor and el Rey

de España, Carlos V or

King of Spain, Charles V, created the Council of the Indies. This

institution of the Crown would oversee its interests in the Nuevo

Mundo. The creation of the Council

would become an extremely important advisory body to the monarch just as

the councils appointed by the monarch with particular jurisdictions in

central Iberia had. Between

1565 C.E. and 1587 C.E., the 16th-Century

C.E., many Spanish cities were established in North and Central

America. España

would attempt to establish missions in what is now the southern United

States including Georgia and South Carolina. Settlement

efforts were successful in the region of present-day Florida. There the city

of San Agustín

or Saint Augustine was founded in 1565

C.E. It is the oldest

European city in the United States. Upon

his arrival, Don António de Mendoza y Pacheco (1495 C.E.-July 21, 1552 C.E.)

was the first Viceroy or Virrey

of Nuevo España

or New Spain, serving from April

17, 1535 C.E. to November 25,

1550 C.E. He was also

the second

Virrey of Peru, from September

23, 1551 C.E. to July 21,

1552 C.E. Don

Mendoza was born at Alcalá

la Real (Jaén, España), the son of the Second Conde de

Tendilla, Íñigo López de

Mendoza y Quiñones and Francisca

Pacheco. He was married

to María Ana de Trujillo de Mendoza. Don Mendoza took

to the duties entrusted to him by the King seriously and vigorously

encouraged exploration of España's

new mainland territories. It

was he that commissioned the expeditions of Francisco

Vásquez de Coronado from 1540C.E.-1542 C.E., into the present day American Southwest. Mendoza

also commissioned Juan Rodríguez

Cabrillo’s exploration up the Pacific Ocean in 1542 C.E.-1543 C.E. Cabrillo

sailed far up the coast, becoming the first European to see present day California, United States. The

Virrey also sent Ruy López de Villalobos to the Spanish East Indies in 1542

C.E.-1543 C.E. As these new

territories became controlled, they were brought under the purview of

the Virrey of Nuevo España. Francisco

Vásquez de Coronado’s

Expedition to Nuevo Méjico

would change the lives of my family, the de

Riberas, forever. Nuevo

España’s Nuevo Méjico

would be visited

many times before permanent settlement. The

first was an accident of fate. The

next visits were spurred by greed. 1526 C.E. Pánfilo

de Narváez

Expedition

It is believed that de

Narváez was born in Castilla

(in either Cuéllar or Valladolid)

España in 1470 C.E. He

was a relative of the first Spanish Gobernador

of Cuba, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar.

António Velázquez de Narváez was his nephew.

Bartolomé de las Casas,

16th-Century C.E. Spanish

historian, social reformer, and Dominican Fray described him as "a man of authoritative personality, tall

of body, and somewhat blonde inclined to redness." The

Expedition’s intent was to establish colonial settlements and

garrisons in La Florida. The

contract provided for a one year timeframe to raise an army, exit España,

found and colonize at least two towns of one hundred people each, and

garrison two additional forts along the coast. At this

juncture, what should strike the reader is the fact that this was the Early-16th-Century C.E., there were no telephones, computers,

Internet, trucks, trains, and aircraft with which to conduct the

business at-hand, for which the proposed expedition only had one yare to

prepare and execute. I’m

sure that the Non-Spanish historians and commentators have dealt with

this trifling issue. Oh,

not! On June 17, 1527 C.E., the Expedition was ready and departed España

from the port of Sanlúcar de

Barrameda at the mouth of the Guadalquivir

River. Among the force were

approximately 450 troops, officers, and slaves. Another

150 members of the Expedition were sailors, wives (Spanish laws stated

that married men could not travel without their wives to the Indies),

and servants. The crew

included members from España,

Portugal, Greece, and Italy. Fortunately for the Expedition, de Narváez had earlier taken part in the Spanish conquest of

Jamaica in 1509 C.E. By 1511

C.E., he had also been in Cuba

participating in its conquest under the command of Diego

Velázquez de Cuéllar. De

Narváez also led expeditions into the eastern end of the island

with Bartolomé de las Casas

and Juan de Grijalva.

He had the experience necessary. Notes: De las Casas’

extensive writings, the most famous being a

short account of the destruction of the Indies and Historia de

Las Indias, chronicled the first decades of colonization of the West

Indies and focused particularly on the alleged atrocities committed by

the pobladores against the indigenous peoples. De

las Casas, an eye witness, reported that Narváez

had presided over the infamous massacre of Caona.

While at the village, the

Spanish troops put to death all natives who had come to greet them with

offerings of food. De

Grijalva

or de Grijalba was born around

1489 C.E. in Cuéllar, Crown of Castilla on

January 21, 1527 C.E. in Nicaragua.

He was a Spanish conquistador, and relation of Diego

Velázquez. He went to Hispaniola

in 1508 C.E. and later to Cuba

in 1511 C.E. De

Grijalva was

one of the earliest explores of the shores of Méjico. According to Pedro

Mártir, there were 300 people with him. The

main pilot was Antón de Alaminos.

The other pilots were Juan Álvarez (also known as el

Manquillo), Pedro Camacho de

Triana, and de Grijalva. Other members

included Francisco de Montejo y

Álvarez

(c. 1479 C.E. in Salamanca-c. 1553 C.E. in

España),

Pedro de Alvarado y

Contreras (Badajoz, Extremadura, España,

ca. 1485 C.E.-Guadalajara, Nuevo España, July

4, 1541 C.E.),

Juan Díaz (1480 C.E.-1549 C.E.),

born in Sevilla,

España,

and was a 16th-Century C.E. conquistador and the chaplain of the 1518 C.E. Grijalva

Expedition, the Itinerario (itinerary route) of which he wrote.

He was one of the first Españoles

who

explored the named Isla de

Sacrificios near Veracruz

in Méjico, where the expedition found evidence of human sacrifice, Francisco

Peñalosa born in Talavera de la Reina in

the province of Toledo. He

spent most of his career in Sevilla,

serving as the Musician/Composer or maestro di capilla, though he

also spent time in Burgos, and

three years in Rome at the papal chapel (1518

C.E.-1521 C.E.) and died in Sevilla,

Alonso de Ávila (Ciudad Real 1486 C.E.-Nueva Galicia 1542

C.E.),

Alonso Hernández, Julianillo,

Melchorejo, and António

Villafaña. They

embarked in the port of Matanzas,

Cuba, with four ships in April

1518 C.E. Pedro

Mártir de Anglería

was an Italian-born historian of España and

its discoveries during the Age of Exploration. Mártir

was born on February 2, 1457 C.E.

and died in October 1526 C.E.

He was formerly known in English as Peter Martyr of Anglería. De

Anglería wrote the first accounts of explorations in Central and

South America in a series of letters and reports, grouped in the

original Latin publications of 1511

C.E. to 1530 C.E. His Decades

are of great value in the history of geography and discovery. His

De Orbe Novo (1530

C.E.) written about the Nuevo

Mundo, describes the first contacts of Europeans and Indigenous,

Native-American civilizations in the Caribbean and North America, as

well as Mesoamerica. It

includes the first European reference to India rubber. Mártir

was born at Lake Maggiore in Arona

in Piedmont and later named for the nearby city of Angera.

He studied under Juan Borromeo, the count of Arona.

At the age of twenty, he

went to Rome and was introduced to a world of powerful men, the

hierarchy of the Catholic Church. After

meeting the Spanish ambassador in Rome, Mártir

accompanied him to Zaragoza

or Saragossa,

España in August of 1487

C.E. By 1488 C.E., he was lecturing at Salamanca

on the invitation of the University. Later,

Mártir would become chaplain

to the court of Ferdinand and Isabella. After 1492

C.E., Mártir's main task

was the education of young nobles of the Spanish court. By

1501 C.E., he was sent to

Egypt on a diplomatic mission. While

there, he dissuaded the Sultan from taking vengeance on the Christians

in Egypt and Palestine for the defeat of the Moors in Spain. Mártir would later describe his voyage through Egypt in the

“Legatio Babylonica,” which he published in the 1511

C.E. edition of his Decades. He

was awarded the title of maestro

de los caballeros (master of knights) for the success of the

mission. In 1520

C.E. Mártir was given the

post of cronista or

chronicler, in the newly formed Council of the Indies. That

commission by Carlos V, Holy

Roman Emperor, was to describe what was occurring in the explorations of La Nueva Mundo. By

1523 C.E., Carlos had made Mártir

Count Palatine. In 1524 C.E., he was once again called to serve the Council of the

Indies. Mártir was invested by Pope Clement VII, having been proposed by Carlos

V, as Abbot of Jamaica. Mártir

was never visit the island, but as abbot he directed construction of

its first stone church. He

died in Granada in 1526 C.E. Grijalva

sailed along the coast of Méjico

and discovered the island Cozumel

or the Island of the Swallows, after rounding the Guaniguanico

in Cuba. It is located

in the Caribbean Sea off the eastern coast of Méjico's Yucatán Peninsula.

Grijalva

would arrive on May 1st, at the Tabasco

region in southern Méjico.

He would be the first Spanish explorer to encounter Moctezuma

II's delegation. One of

those natives would join the Grijalva

party, being baptized as Francisco,

and became an interpreter on Cortes'

expedition. Bernal

Díaz del Castillo would later write about the travels of Juan

de Grijalva. Grijalva

died in Nicaragua on January

21, 1527 C.E. The men’s names in

paragraph above, in and of themselves say little. These

were interesting, multi-faceted, men with great strengths and complex

pasts and why we took these cardboard figures and fleshed them out. It

is hoped that by adding this additional information on men like De las Casas, Mártir,

and Grijalva the reader can

gain a greater understanding of these Spaniards and their capabilities. España was a great

empire with very learned subjects. They

were not just conquerors. Unfortunately,

British, Anglo-American, Northern European, and other non-Spanish

historians and commentators paint with a broad brush and miss the

details necessary to give a fair assessment of these Spanish explorers,

who they insist on portraying as only one dimensional “Conquistadores”

or conquerors. In

1519 C.E., the Gobernador of Cuba, Diego

Velázquez de Cuéllar, authorized Hernán Cortés to lead an expedition into Méjico. Later, he would

determine that Cortés'

loyalty was to himself. He

then attempted to recall the expedition shortly after its embarking. Cortés

disobeyed and proceeded with the expedition which would eventually

result in the defeat of the Azteca

(Aztec) Empire. After Narváez

arrived in Méjico from Cuba,

he was named Gobernador of Méjico by Velázquez

who had sent him along with 1400 men on 19 ships to arrest Cortés. Narváez

disembarked at Veracruz (Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave).

There, Cortés

had left behind Capitán Gonzalo de Sandoval

with a small garrison before setting out for the Azteca

capital of Tenōchtitlan. They

had arrived together in La Nueva

España earlier, in 1519 C.E.

He managed to capture some of Narváez's

troops and sent them forward to Tenōchtitlan

alerting Cortés of the coming danger. Narváez

had been unable to defeat the garrison and left for Totonac,

a town in Cempoala (Zempoala), where he established a camp. News

soon arrived that Narváez was

near. Cortés

and a contingent of his troops (As few as 250 men) returned to the

coast. On May

27, 1520 C.E., Cortés’

small army, under the cover of a driving rain, moved against Narváez's encampment at Cempoala or Zempoala. He rapidly gained control of

the artillery positions and the horses before entering the city.

Narváez with a

contingent of musketeers and crossbowmen took a position at the main

temple of the city of Cempoala

awaiting an attack. It

was de Sandoval, the youngest

of the Tenientes of Cortés, who seized the messengers of Pánfilo de Narváez after demanding their surrender. He

then sent them as prisoners to Cortés.

He would later arrive at Totonac with reinforcements. Cortés

then managed to set fire to the main temple, driving out Narváez and his soldiers. In

the ensuing battle, it was de

Sandoval who captured Narváez.

Narváez

was badly wounded and lost an eye during that battle.

Afterwards, he was taken prisoner and spent two years at the

garrison at Veracruz before

being sent back to España. Once

defeated, Narváez’ men were promised gold by Cortés if they would join his army and return to

Tenōchtitlan.

They agreed and later

participated in the conquest of the Azteca

Empire. Unfortunately, a

deadly outbreak of smallpox spread from Narváez's

party to the native population of La

Nueva España and killed many. After

the subjugation of Moctezuma II (c.

1466-June 29, 1520 C.E.) or also Moteuczoma,

Xocoyotzin

(Moctezuma the Young),

who was the ninth tlatoani or ruler of

Tenōchtitlan, Cortés

placed de Sandoval in command at Villa

Rica de Veracruz as alguacil mayor or Chief Constable. The

aforementioned notes have been provided to ensure the reader has a

greater understanding of these Españoles.

Too often, non-Spanish

historians and commentators offer cardboard cut-out caricatures of these brave

and gallant men. They were

not just conquistadores

they were in fact flesh and blood human beings. In

short, they had lives before the conquest of Méjico. At about a

week's journey or 850 miles into the Atlantic, the fleet’s first stop

was made at the Islas Canarias.

There the expedition took on

needed supplies such items as water, wine, firewood, meats, and fruit. The

fleet proceeded to continue its journey and make stops at La Española

or Hispaniola and Cuba. They had

arrived in Santo Domingo, La

Española in August of 1527

C.E. The expedition was

there to purchase horses, as well as two small ships for exploring the

coastline. During their

stay, members of the expeditionary force began deserting. Approximately

100 men deserted in that first month at Santo

Domingo. Narváez was only

able to purchase one small ship. He

then set sail once again. Narváez

would sail four of his six ships to the Gulf of Guacanayabo a bay along the southern coast of Cuba, bordered by Granma

and Las Tunas provinces.

He had sent his other two

ships under the command of Cabeza

de Vaca and Capitán Pantoja to Trinidad or

Trinity to acquire additional supplies and seek additional crew members.

The ships arrived in Trinidad about October 30th.

Shortly after their arrival a hurricane hit. The

storm sank both ships. 60

men died, one fifth of the horses drowned, and the new supplies acquired

in Trinidad were destroyed. Recognizing the

need to regroup, Narváez sent

the four remaining ships under command of Cabeza

de Vaca to Cienfuegos. It

is the capital of Cienfuegos

Province, a city on the southern coast of Cuba.

After staying ashore at the Gulf of Guacanayabo nearly

four months, he had recruited men and purchased more ships.

Narváez sailed one of

his two new ships to Cienfuegos

and arrived on February 20, 1528

C.E., with a few more recruits. This

would bring the expedition’s strength to about 400 men and 80 horses. The

other ship he had sent on to La Habana or Havana. By

this time, the winter layover had caused a depletion of supplies. Narváez

was planning to restock once the fleet arrived in La Habana on its way to the La

Florida (flowery land) or Florida coast. Unfortunately,

two days after leaving Cienfuegos,

every ship in the fleet ran aground in the region of Archipiélago

de los Canarreos

on

the Canarreos shoals just off

the coast of Cuba. They

remained there unable to free themselves for two to three weeks. It

was not until the second week of March, that a storm created large seas

allowing them to escape the shoals. Once

on their way, they battled more storms while rounding the western tip of

Cuba and attempting to make their way to La Habana. The

expedition neared La Habana

and was close enough to see the masts of ships in port. However,

the winds blew the entire fleet into the Gulf of Méjico and it was unable to reach La Habana. By then, the

men had depleted the already meager supplies. Understanding

his predicament, Narváez

decided his only course of action was to press on with the journey to along

the northwestern Gulf coast just north of Cortés'

La Nueva España colony

and establish the Expedition’s required colonies. The

fleet spent the next month attempting to reach the Mexican coast. However,

they could not overcome the Gulf Stream's powerful current.

On 12th day of April, 1528 C.E., the expedition spotted land north of

what is now Tampa Bay, La

Florida. The decision

was made to turn south and look for what the pilot described as a great

harbor. They then traveled

for two days. One of the five remaining ships was lost during that two

day journey. After the fleet

spotted a shallow bay, Narváez

ordered entry. It was just

north of the entrance to Tampa

Bay that the fleet passed into Boca

Ciega Bay and spotted buildings set upon earthen mounds. These

they saw as encouraging signs of habitation, food, and water. The

natives have been identified as members of the Tocobaga

or Safety Harbor Culture. Los Españoles then dropped anchor and went ashore. It

was near the Río de las Palmas, at what is known as the Jungle Prada

Site in present day Saint Petersburg, where Narváez

landed his 300 men. Making their

way to a nearby village, the Españoles

traded items such as glass beads, brass bells, and cloth for fresh fish

and venison. There was little wealth among the people, but they were

peaceful. That night the

villagers abandoned their homes and fled the strangers. Several members

of the expedition spent the next day exploring the empty village. Narváez

then ordered the remainder of the company to debark and establish a

camp. The following day, the

royal officials assembled ashore to perform a formal declaration of Narváez as royal Gobernador

of La Florida. He

read the Requerimiento or "requirement" a "demand"

which was a written declaration of sovereignty and war. Read

by Spanish military forces, it asserted their sovereignty, a

dominating control. It

stated to any natives listening that their land belonged to Carlos

V of España by order of

the Catholic Pope. It also

provided that the natives had the choice of converting to Christianity. Later, Narváez and some other officers would discover Old Tampa

Bay after some exploration. Once

they returned to camp, Miruelo,

the pilot, was ordered to take a brigantine and search for the great

harbor he had talked about. If

he was unsuccessful, he was to return to Cuba.

Narváez

was never to hear from him or any of the crew again. Shortly

thereafter, Narváez took

another party inland, where they found a village. There

los Españoles found a little

food and gold. The Natives

explained that there was far more of both in Apalachee to the north. Los

Españoles returned to their base camp and made plans to head north.

1532 C.E. Álvar Núñez Cabeza

de Vaca

Expedition It was Álvar Núñez Cabeza

de Vaca who argued against the Narváez

plan.

This was no small matter.

While de Vaca was

attached to this expedition as the expedition’s treasurer, he was not

simply an administrator. He

was born around 1490 C.E.

into a Spanish hidalgo family,

in the town of Jerez de la

Frontera, Cadiz, España. De Vaca was appointed chamberlain for the house of a noble family in

his teen years. He later

participated in the conquest of the

Islas

Canarias where he was appointed a Gobernador.

By 1511

C.E., he had enlisted in the Spanish army. He

served in Italy (with distinction), España,

and Navarra or Navarre. He

had received several medals’ of honor.

De Vaca also became a

political figure in España.

In 1527 C.E., Núñez joined

the La Florida Expedition of Pánfilo

de Narváez during which he served as treasurer and marshal.

However, records indicate that he also had a military role as one

of the chief officers on the Narváez

Expedition, noted as sheriff or marshal. However, his

suggestion was voted down by the other officers. Narváez

then wanted de Vaca to lead the sea force. De

Vaca refused, as he felt it was a matter of honor, since Narváez had implied that he was a coward. For two long,

hard weeks the men marched before finding a village north of the

Withlacoochee River. By that

time they were near starvation. The

men held the natives captive for three days and ate from the corn

fields. They then sent two

exploratory parties downstream on both sides of the river to attempt to

locate their ships. Narváez

ordered the party to continue northward to Apalachee when he saw no

signs of the ships. De

Vaca

would learn what became of the ships several years later. The

Pilot, Miruelo, had returned

to Old Tampa Bay and found

that all of the ships were gone. He

then sailed to La Habana to

pick up a fifth ship that had been supplied. Miruelo

then returned to Tampa Bay. The

small fleet of ships headed north for some time unable to find the party

on land. The commanders of the other ships decided to return to Tampa

Bay. After meeting, the

fleet again searched for the land party. The

search would go on for nearly a year before they departed for Méjico.

A member of that naval

force, Juan Ortiz, had been

captured and enslaved by the Tocobaga. He

lived at Uzita, the chief town

near the mouth of the Little Manatee River on the south side of Tampa Bay, La Florida for

nearly twelve years before being rescued by

Hernándo de Soto's Expedition. It

is in the area of Hillsborough County that is now Ruskin, Florida.

The territory of Uzita is reported to have extended from the Little Manatee River to Sarasota

Bay. Uzita

were part of the Safety Harbor culture. In 1528 C.E.,

as the party of Españoles

neared the Timucua

territory their scouts reported their coming. At

the time of European contact, the territory occupied by speakers of Timucuan

dialects occupied about 19,200 square miles (50,000 km) from Northeast

and North Central La Florida

through Southeast Georgia. This

was the home of 50,000 to 200,000 Timuacans.

It stretched from the Altamaha River and Cumberland Island in present-day Georgia as far

south as Lake George in Central Florida,

and from the Atlantic Ocean west to the Aucilla

River in the Florida

Panhandle. It continued

though to the Gulf of Méjico.

They were the largest

indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, some

the head of thousands of tribal members. On June 18, 1528 C.E., the Timucua

decided to meet the Españoles

as they came near. Using

hand signs and gestures, Narváez

was able to communicate with their chief, Dulchanchellin.

He explained that they were

headed to Apalachee territory. As

the Apalachee were his enemies, Dulchanchellin

was pleased by this plan. After

exchanged gifts, the expedition followed the Timucua

into their territory and crossed the Suwannee River. The Españoles arrived at a Timucua

village on June 19, 1528 C.E.

The chief sent the

expedition provisions of maize as a gesture of friendship. That

same night, an arrow was shot at one of Narváez's

men near a watering hole. The

next morning, the Españoles

found that the Timucua had

deserted their village. Narváez's

expedition set out again for Apalachee. They

soon understood that they were being followed by hostile Indians. Narváez

quickly laid a trap for the pursuing hostiles and captured several. They

were soon used as guides. After

this, the expedition had no further contact with the Timucua. Apalachee

territory was entered by the expedition on June

25, 1528 C.E. They soon

found a community of forty houses which they believed to be the capital.

But it was only a small

outlying village of a much larger tribal culture. The

Españoles took the community

and several hostages, including the village's cacique. After occupying the

village, the Españoles found

none of the gold or other riches Narváez

was expecting. But they did

find a great deal of maize. Apalachee

warriors began attacking the Expedition soon after Narváez

took the village. Their

first attack was with a force of 200 warriors. These

used burning arrows to set fire to the houses the Europeans had

occupied. The experienced

warriors soon quickly dispersed, losing only one man. The

following day, a second force of 200 warriors attacked from the opposite

side of the village. The

force quickly dispersed after losing one warrior. The

Apalachee would change to rapid assaults after their two direct attacks. As the Españoles

started moving deeper into their territory, the warriors continued to

harass them. During combat

the Apalachee were able to get off five or six arrows with their bows in

the time it took the Españoles

to load a crossbow or harquebus. The

warriors would then fade into the woods. For

the next several weeks, they harassed the Españoles

continuously in what later become known in warfare as guerrilla tactics

or guerilla in Spanish, which is an irregular soldier or a terrorist. Guerra

is skirmishing warfare in Spanish, Italian and Portuguese; the French

spell it guerre. Moving forward,

Narváez dispatched three

scouting missions in search of larger, wealthier towns. All

three returned with disappointing news. By

now, Narváez’s health was

failing. He was also

frustrated by his misfortune. He

next ordered his expedition to head southward. At

this point, Narváez had both

Apalachee and Timucua

captives. Both tribal

members told him that the Aute,

an Apalachee village, had a great deal of food, and the village was

located near to the sea. Unfortunately,

to get to the Aute, the Españoles had to cross a large swamp. The

Españoles

were not attacked for the first two days before reaching the village. However,

the stealthy Apalachee attacked them with showers of arrows during their

swamp crossing while they were up to their chests in water. The

crossing had left the Españoles

nearly helpless as they could use neither their horses, nor quickly

reload their heavy weapons. They

also found that their heavy armor weighed them down in water. Soon

after finally regaining solid ground, los

Españoles drove off the warriors. For

two more weeks, they continued their difficult trek through the swamp,

under intermittent attack by the Apalachee. The

Españoles,

many of whom were starving, wounded and/or sick, finally arrived at Aute.

The village was by then

deserted and portions had been burnt. Fortunately,

they were able to harvest enough corn, beans, and squash from the

village gardens to feed their party. After

some days, Narváez dispatched

de Vaca to find an opening to the sea. Unfortunately,

he was unable to locate a path to the sea. However,

after half a day's march along the Wakulla

River and Saint Marks River de

Vaca located some shallow, salty water filled with oyster beds. After

two additional days of scouting, no better results were produced. The

disappointed men would return to Narváez

with the news that no path to the sea was located. Many of the

horses were by then used carrying the sick and wounded. It

was at this point that the Españoles

realized they were struggling to survive. Narváez

made a desperate decision to return to the oyster beds for the food, as

members of his expedition had begun to consider cannibalism as a means

for survival. During the

march, some of the members of the party talked about stealing their

horses and abandoning the expedition. Narváez

was by then too ill to take action. It

was de Vaca who learned of the

plan and convinced them to stay. Comments: I have provided the reader with the details of the

fighting, battles, and skirmishes against the Indigenous with the

purpose of dispelling the notion often set forth by non-Spanish

historians and commentators that the Españoles

only won militarily due to their superior armaments and protective

battle armor. It is clear

that neither was of value under these environmental conditions. What should also be noted here is that it is Spanish

bravery and perseverance which allowed them to overcome being cut-off

from outside help, without food and supplies, and without proper

determinants of geography and environment. It

was all of these factors that decisively affected the nature or outcomes of

the success of the Spanish expedition, and over these they had no

control. I’m positive that

have been glossed over or treated as an aside by the non-Spanish

historians and commentators. On August 4, 1528 C.E., after a few days stuck near the shallow waters,

a member of the expedition conceived a plan to reforge weapons and armor

to manufacture tools for the building of new boats to sail to Méjico. The party

soon began on the work. By September

20th, the exhausted men had finished building five boats. This

was a sign of Spanish ingenuity under the worst of circumstances. The Españoles had traversed hostile environments, lacked of proper

information for exploration routes, and received misinformation about

the riches and food held at their ultimate destinations. In

addition, they were ravaged by disease and suffering from starvation. To

make matters worse, the Españoles

had been attacked by the very tribes they intended to conquer.

In the end, only 242 of the party had survived. On

September 22, 1528 C.E., about 50 men would be carried by each of

the thirty to forty feet long, shallow draft boats, with sail, and oars.

Unfortunately, for the

pummeled Spaniards, their problems had only just begun. Later, the expedition would be further reduced to about 80

survivors by storms, thirst, and starvation. The

party would next be forced by a hurricane onto the western shore of a

barrier island. Some

historians believe they had landed on present-day Galveston, Texas or Tejas

(Then a part of Nuevo España of el Imperio

Español). For the next

four years, de Vaca and what

was left of his party would survive in the Indigenous world of South Tejas.

By July 1536 C.E., while near Culiacán

in present-day Sinaloa, the

four survivors encountered a party of Españoles

then on a slavery expedition for La

Nueva España. De Vaca later wrote that his countrymen were "dumbfounded at

the sight of me, strangely dressed and in the company of Indians. They

just stood staring for a long time." The

Spanish slavery expedition gave aid and comfort to the survivors and

accompanied them to Méjico City. Estéban

or Estevanico would later serve as a guide for other

expeditions. De Vaca returned to España

and wrote a full account of the ordeal, describing at great length the

many indigenous peoples encountered. He

would later serve the colonial government in South America. Comments: I decided to offer the

aforementioned to educate the Anglo Saxon, Northern European, and other

Non-Spanish historians and commentators who would forget the reality of

the situation or if mentioned, treat it as an aside. Let

me make the point one more time. Given

the period in history and the available technology there could be no

plans for assistance. These Españoles were alone, cut-off, and on their own. This

meant that they had to be brave, courageous, resolute, and above all

competent. I’m sure

that the non-Spanish historians and commentators would apply these last

characteristics to non-Spanish explorers only, to the exclusion of the

Españoles. After all,

these sole surviving four men out of an original three hundred, who

continued to persevere and survive this arduous journey surely

couldn’t, have had the kind of courage accorded only to non-Spaniards.

After all, for non-Spanish

writers of history, these men were only blood thirsty destroyers of the

civilization of the Noble Savage, and nothing else.

1539 C.E. The Fray Marcos de Niza

Expedition

He

was a friar of the Catholic Franciscan Order. After

becoming a Franciscan, Fray Marcos

had immigrated to the Nuevo Mundo

(Americas) in 1531 C.E.,

going to Santo Domingo as a

missionary and later and served in Peru,

Guatemala, and Méjico

city. While at Culiacán,

Méjico,

he was reported to have freed Indian slaves from regions to the

north. By

1539 C.E., he was ordered by

the Virrey of la Nueva Espania, António de

Mendoza, to lead an investigative expedition across the desert to

the cities of Cibola or Cevola

(1539). Why? Because

reports made by Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and three companions had raised hopes

in Méjico

of fabulous riches to the north. Mendoza

was already preparing a larger, military expedition to be headed by Francisco

Vásquez de Coronado. In

1539 C.E., Fray Marcos de Niza was to

be dispatched with Estéban the Moroccan-Berber companion of Cabeza

de Vaca in his ill fated wanderings to explore in advance. Once

prepared, Fray Marcos

left Culiacán, a city in

northwestern Méjico, in March 1539 C.E.

He had been authorized by the Spanish government to conduct a

preliminary exploration of the country north of Sonora

to determine the truth of these reports. Estéban acted

as the expedition's guide. Fray Marcos,

Estéban, and the expedition set out with great hopes of discovering the fabled Quivira

and its streets of gold. He

would then cross south-eastern Arizona

near present-day Lochiel. His

party penetrated Zuni lands searching for the Seven Cities of Copala, Cevola, or Cibola. When the Expedition approached the

Zuni pueblo of Hawikuh in western Nuevo Méjico

to what is today southern Arizona, Estéban and several companions went ahead scouting the country.

A system of signals was devised so they could report to the Fray

about what they had found. If

it was of little important, they were to send back a Christian cross the

size of a man's palm. If

important, the signal would be one of larger crosses. One

can only image Fray Marcos'

surprise. The messengers

returned bearing a cross the size of a man. They

also reported that Estéban had learned of a place called Cibola

and that he had been told this Cibola

was but one of seven magnificent cities. Fray Marcos would rush

forward, anxious to glimpse the marvelous sight which had prompted the

report. However, shortly

thereafter the Fray met

several of Estéban's companions who would report that their colorful guide had

been killed. When

Fray Marcos learned of Estéban’s

death, he continued pressing on. The

party was under escort by friendly Mexican Indians.

It is reported that Fray Marcos saw Hawikuh

from a neighboring hillside. It

is suggested that he saw the sun shining on the dwellings which made

them appear like gold and silver. It

was this sighting that must have given him such a distorted impression

of the Hawikuh site. Fray Marcos believed he

had seen one of the "Seven Cities."

Legend had originally located them on an Atlantic island. However,

by that time in history, they were now thought to be westward. Fray Marcos' report offers

that he was determination to see the city of Cibola

for himself. The news of Estéban’s death had not deterred him. Marcos

continued on until he came within sight of a settlement which he

describes as being larger than the city of Méjico. What he saw

was only Cibola, but from a

distance. He also commented

that his Indian guides had told him this Cibola

was the least of the seven great cities. Unfortunately

for him, the Fray offered mere

hearsay in his report, Descubrimiento de las siete ciudades. But by September

1539 C.E., he would

return to Culiacán. One

can only infer that the others in the party were driven by gold and what

it could buy them on their return to civilization. They

would all be very disappointed. Fray Marcos was made

provincial superior of his order for Méjico before the second trip to Zuni. Upon

returning to Méjico,

Fray Marcos described the

place as larger than Méjico

City, with houses 10 stories high whose doors and fronts were made of

turquoise. With this report,

Mendoza needed no more convincing. The

Coronado expedition, with the Fray

as guide, would depart early in 1540

C.E. They reached Hawikuh on July 7th and

captured it. But the

soldiers were enraged on finding nothing but a poor Indian village. They

cursed the Fray so vehemently that Coronado,

not wishing to have the blood of a churchman on his hands, sent him back

to Méjico

City. The accompanying

message stated, "Fray Marcos

has not told the truth in a single thing that he said." Niza

would become provincial of his order for Méjico

in 1541 C.E. The rest of

the friar's career proved uneventful. He

apparently became stricken with paralysis and lived first at

Xalapa or Jalapa

and then in a monastery at Xochimilco.

Bishop Juan de Zumárraga would give him aid until his own death in 1548

C.E. Nothing more is

known other than that the friar died on March

25, 1558 C.E. It had been the hearsay in the Fray’s report which had led Francisco

Vázquez de Coronado y

Luján to make his famous expedition in the year of 1540

C.E., to the Zuni Pueblo, in present-day Nuevo Méjico.

To make matters worse, Fray

Marcos was to guide that

expedition and the realities of it that proved to be a great

disappointment. He would

return in 1541 C.E., to the

capital in shame. For a time

would be able to exercise the highest office of the Franciscans, in the

province. 1540

C.E. Francisco

Vázquez de Coronado y Luján

Expedition Next,

Don Francisco Vázquez de Coronado y

Luján would

explore Nuevo Méjico from 1540

C.E.-1542 C.E. The Coronado

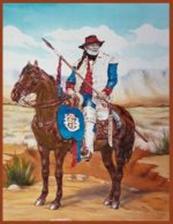

Expedition consisted of 250 horsemen, 70 foot soldiers, 300 native

allies, and over a thousand servants and dependents from Culiacán.

He led his troops on the

Gulf of California across the

mountains and into the desert in search of the glorious Seven Golden

Cities of Cibola of gold which

he had heard described by guide Fray

Marcos de Niza. Discouraged

by the reality of the adobe pueblos, Coronado sent a

small force to the west, where progress to the sea was blocked by the

Grand Canyon. However,

his were the first Europeans to sight the Grand Canyon and the Colorado

River, among other landmarks. The

Spanish forces wintered at Kuaua

Pueblo (present day Coronado

State Monument), and then set off to find Quivira

in the plains. The army

travelled the trackless prairie as far as present day Kansas, saw and

hunted bison, met the Wichita, and finally returned to

La Nueva España "disappointed, weary, and worn out. An

eyewitness, Pedro Reyes Castañeda, accompanied Don Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to Nuevo Méjico in 1540 C.E.-1542

C.E., and his work comprises the bulk of what we know of this

expedition. This Spaniard

wrote his observations about the journey. Doubtless,

these men were disappointed to have failed at finding that great prize,

the seven Golden Cities of Cibola. There

were two Ribera/Rivera surnamed individuals with the Coronado Expedition: Blaque,

Tomas was from Escocia or

Scotland and was married to Francisca

de Rivera. Antonio de Ribera

was the second. 1563

C.E.-1565

C.E. Francisco de Ibarra Explorer of Nuevo

Méjico Between

1563 C.E.-1565 C.E., Francisco de Ibarra

(b. 1539 C.E.?- d.

1575 C.E.) explored Nuevo

Méjico. He was a

Spanish Vasco or Basque explorer and Gobernador of the Spanish province of New Biscay or Nueva

Vizcaya, in present-day Méjico.

De

Ibarra was born in Eibar, Guipúzcoa,

in the Basque Country of España.

He went to Méjico

as a young man, and upon the recommendation and financing of his uncle,

conquistador and wealthy mine owner Diego

de Ibarra, Francisco was

placed at the head of an expedition to explore northwest from Zacatecas in 1554 C.E. The

young de Ibarra

noted silver in the vicinity of present-day Fresnillo,

but passed it by. He

explored further and founded towns at San

Martín and Avino, where

the silver mines made him a mine owner in his own right. In

1562 C.E., de Ibarra headed another

expedition to push farther into northwest Méjico.

In particular, he was

searching for the fabled golden city of Cibola.

He did not find the mythical

treasure, but explored and conquered what is now the Mexican state of Durango. De

Ibarra was then appointed Gobernador

of the newly formed province of Nueva

Vizcaya in 1562 C.E., and

the following year he founded the city of Durango

to be its capital. In

1564 C.E., de Ibarra followed rumors of rich mineral deposits and crossed the Sierra

Madre Occidental in western Méjico

to conquer what is now southern Sinaloa.

Prospectors discovered

silver veins in the new territory, and in 1565

C.E., de Ibarra founded

the towns of Copala and Pánuco. Soldiers

under de Ibarra's direction explored north from Durango in 1567 C.E., and

founded the town of Santa Bárbara

in present-day Chihuahua to

mine the silver they found there. Francisco

de Ibarra died on June 3,

1575 C.E. in Pánuco, Sinaloa, one of the silver-mining cities that he founded. What

began simply as a search of gold became the ongoing settlement of the

most northern areas of Nueva España. The sites

would grow and become heavily populated. 1580

C.E., Rodríguez-Sánchez

Expedition of

Nuevo Méjico By

1580 C.E., Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado (ca.

1512 C.E.-1582 C.E.), a Capitán in the Spanish army, was

exploring Nuevo Méjico. Sánchez

was called Chamuscado because

of his flaming red beard. He

was the military leader of the Rodríguez-Sánchez

Expedition, which left the Spanish outpost of Santa

Bárbara on June 6, 1581 C.E.,

to search for Indian settlements beyond the jurisdiction of Nueva Vizcaya. The

expedition crossed the Río Grande,

probably at La Junta de los Ríos,

and visited Jumano settlements

at a site near that of present Presidio.

There appears to be a debate

as to who was the actual leader of the Rodríguez-Sánchez

Expedition. Sánchez died on the return trip, sometime between January

31, 1582 C.E. and April 15,

1582 C.E., in Méjico at a

place called El Xacal, near

the site of modern Julimes, Chihuahua. Soon after

the evangelization would begin, the sword and shield had advanced before

the cross. Evangelization

began in Santa Bárbara in 1581

C.E. Fray

Agustín Rodríguez

heard of an advanced civilization to the north. Given

official permission to evangelize, he set off with a small party under

the command of Capitán

Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado.

The party reached the vicinity of Socorro

in August. For the following

five months, they explored the Río

Grande pueblos. Leaving behind

two priests to continue religious conversion, the main party returned in

1582 C.E. The

two unprotected priests would be murdered. A

controversy would later arise because Chamuscado

had left them behind at their insistence, but unprotected. Hernán Gallegos

was one of nine laymen selected to accompany the Rodríguez-Sánchez

Expedition

of

Nuevo Méjico. He

along with two other men testified post-Expedition regarding the events

that transpired about the two of the priests which had been left behind

and were killed. 1582

C.E.-1583 C.E. Don António de

Espejo Expedition Between

1582 C.E. and 1583 C.E., caught up in the excitement caused by the returning Chamuscado-Rodríguez expedition el Español

Don António de Espejo

underwrote the costs of a second expedition. Espejo was born about 1540 C.E. in

Córdoba, España, and arrived in

Méjico in 1571 C.E.

along with the Chief Inquisitor, Pedro

Moya de Contreras, who was sent by the Spanish king to establish an

Inquisition.

In 1582

C.E., he led a small group to explore Nuevo

Méjico. A

wealthy man, Espejo, financed

and assembled an expedition for the purpose of ascertaining the fate of

two priests who had remained behind with the Pueblos

when Chamuscado led his

soldiers back to Méjico. The

Expedition included fourteen soldiers, a priest, about 30 Indian

servants and assistants, and 115 horses. The

party departed from San Bartolomé,

near Santa Bárbara, on November 10, 1582 C.E. Espejo

followed the same route as the

Rodríguez-Sánchez Expedition, down the Conchos

River to its junction (La Junta)

with the Río Grande and then

up the Río Grande to the Pueblo villages. Along

the Conchos River, Espejo

encountered the Conchos

Indians, "naked people...who support themselves on fish, mesquite,

mescal, and lechuguilla (agave)."

Moving further downriver,

the party found Conchos

growing corn, squash, and melons. Espejo moved on leaving the Conchos

behind. He next encountered

the Passaguates "who were

naked like the Conchos"

who appeared to live a similar existence. The

Expedition soon came upon the Jobosos

who were few in number, shy, and ran away from the Spaniards. Eventually,

the early Spanish in Nuevo Méjico

would become familiar with the Río

Grande Jumanos. The explorers

often describe any tattooed native as a Jumano.

Espejo

would find five settlements of Jumanos

tribes with a population estimated at 10,000 members.

It is reported that they lived in low, flat roofed houses. The

Jumanos grew corn, squash, and beans. They

also and hunted and fished along the river. Espejo was given well-tanned deer and bison skins by them. There

are also reports that some were reported to have lived near the Salinas

east of the Manzano Mountains.

Explorers described two

other bands of Jumanos, who

they claimed may have been related. Therefore,

the record remains unclear. One

particular band appears to have been buffalo hunters in the Southern

plains of Tejas.

Another band was observed

living near La Junta de los Ríos, between the Río Conchas, or Pecos

River, and the Río del Norte

or Río Grande. The

Expedition left behind the Jumano

and passed through the lands of the Caguates

or Suma. These

spoke the same language as the Jumanos,

Tanpachoas or Manos. Near

La Junta of the Conchos and the Río Grande,

Espejo entered the territory

of the Patarabueyes.

The Indians attacked his horses and killed three. After

the attack, Espejo made peace

with them. Espejo

found the Río Grande

Valley well populated all the way up to the present site of El Paso, Tejas.

There he found tribes called

Otomoacos and Abriaches. Upstream from

El Paso, the expedition

traveled 15 days without seeing anyone. By

February 1583 C.E., Espejo’s

party arrived at the territory of the Piros,

the most southerly of the Pueblo

villagers. From there the Españoles continued up the Río Grande. The

Pueblo villages were described

as "clean and tidy," with houses made of adobe

bricks and were multi-storied. Some

of the Pueblo towns were large. Espejo

described Zia as having 1,000 houses and 4,000 men and boys. The

Pueblos used irrigation for

farming, "with canals and dams, built as if by Spaniards." The

only Spanish influence noted by Espejo

among the Pueblos was their

desire for iron which they stole whenever and where ever possible. The

southernmost Pueblos used only clubs for weapons and a few "poor Turkish

bows and poorer arrows." Further

to the north, the Indians were better armed and fierce. Espejo’s

Expedition also explored the Verde

River valley of Arizona

looking for silver mines. He

visited the Zuni and Hopi where he

heard stories of silver mines further west. With

only four men and Hopi guides Espejo went in

search of those mines. It is

reported that his party reached the Verde

River in Arizona, most

probably in the area of Montezuma

Castle National Monument. There,

he located mines near present day Jerome, Arizona.

Unfortunately, he was

unimpressed with their potential. Among

the Hopi and the Zuni, he met several Spanish-speaking Mexican Indians who had been

left behind by, or escaped from, the Coronado

Expedition of 40 years earlier. Finally,

Espejo confirmed the killings

of the two priests in the Pueblo

of Puala, near present day Bernalillo.

When the Españoles approached the Pueblo, its inhabitants fled to the nearby mountains. The

Españoles

continued

their explorations, east and west of the Río

Grande. Near

Acoma, the Españoles

noted

that a people called Querechos

lived in the nearby mountains and traded with the local townspeople. The

Querechos were found to be Navajo.

The Apache

of the Great Plains who were closely related to the Navajo during this period were also referred to as Querechos. Finally,

tired of the journey, several of the soldiers, Indian assistants, and

the priest decided to return to Méjico. Despite

Espejo's entreaties to stay,

the priest most probably offended by the high-handed tactics of Espejo toward the Pueblos

and their natives, left. Espejo

and eight of his soldiers would remain behind to search for silver and

other precious metals. Later,

his small force skirmished with the Indians of Acoma, supposedly over their aiding in the escape of two Spanish

female slaves or prisoners. The

Españoles

recaptured

the women, but after a brief time, the Acoma

wounded a Spanish soldier while aiding her escape a second time. In

aiding in the escape of the women, the Acomans

and Españoles exchanged fire. This

was notice to the Españoles

that

the hospitality of the Pueblos

had come to an end. The

Spanish soon returned to the Río

Grande Valley where they

killed some Indians at a village when an altercation took place over the

Spanish being mocked and refused food. The

Españoles

then quickly departed the Río

Grande exploring eastward.

They journeyed through the Galisteo

Basin near the future city of La

Villa Real de la Santa Fé de San Francisco de Asís, means “Holy

Faith” (Santa Fé, )

Nuevo Méjico

and reaching the large pueblo

at Pecos, called Ciquique. Rather

than return to the Río

Grande Valley, Espejo decided to make his way to Méjico

via the Pecos River which he

named "Río Grande

de Las Vacas" because of

the large number of bison the Españoles

encountered

while following the river downstream. After

descending the river about 300 miles from Ciquique

the soldados met Jumano Indians near Pecos,

Tejas who guided them across

country up Toyah Creek and

cross country to La Junta.

From there they followed the Conchos

River upstream to San Bartolemé, their starting place. They

arrived on September 20, 1583 C.E. They

soon learned that the priest and his companions had also returned

safely. Espejo

was the first European to traverse most of the length of the Pecos

River. On their return to Méjico, reports written by Espejo

and by expedition member, Diego Pérez de Luján, added to a

growing knowledge about the pueblo

people of Nuevo Méjico. Espejo

died in 1585 C.E. in La Habana,

Cuba. He

was en route to Españia to attempt to get royal

permission to establish a Spanish colony in

Nuevo Méjico. 1590 C.E. Gaspar

Castaño

de Sosa Expedition By

1590 C.E., King Felipe II (21 May 1527 C.E.-September 13, 1598

C.E.)

or Philip II of España was

still deciding on a course of action. Gaspar

Castaño de

Sosa,

Lieutenant (Teniente)-Gobernador

of Nuevo León

in

northeastern La Nueva España, also thought that great riches could be discovered in Nuevo

Méjico. De

Sosa was born about 1550

C.E. in Portugal. He is

believed by many authorities to have been a converso or

"Crypto-Jew." This

meant that he was acting as a Christian but secretly continued the

practice of Judaism. Castaño

appears in the history of northern Méjico about 1579 C.E. when along with Luis

de Carabajal y Cueva he was one of the early pobladores in what

became the Mexican state of Nuevo León. Carbajal

was Gobernador of the province and Castaño

had become Teniente-Gobernador. Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva

(c. 1539

C.E.-1595

C.E.)

was a Spanish-Portuguese adventurer, slave-trader. It

is suggested that the Carabajal family did very well financially. The

two men appear to have made their fortunes capturing and selling Indian

slaves in concert with their group of more than sixty soldiers. It

was their practice to raid north along the

Río Grande. There

they captured hundreds of Indians which they sold into slavery. However,

the Spanish government wanted to discourage slavery of Indians in order

to subdue their unrest and this would have impacted the family’s

source of income. Carabajal

was the head of a family of Jewish converts to Christianity or Conversos. The province

Nuevo León was very isolated and constant attack from hostile

Native-American tribes. In

order to attract Spanish pobladores the Crown exempted it from Blood

Purity Laws. This meant

lifting the requirement that only Old Christians (For three generations

or more) could settle the province.

It would appear that it became a destination for other Conversos,

including those related to the

Gobernador. Gaspar

Castaño

de Sosa searched

for Indians in the area that were known to have knowledge of great

riches in that undiscovered area. While

testing their ore, he took a silver cup and threw it in with the test

ore. The rocks were found to

have a high silver content.

His journey

appears to have been both a flight from prosecution and an exploration. Castaño

was accompanied by the Spanish inhabitants of the town. The

future pobladores took with them a large number of livestock and

possessions in the wagon train. Oddly,

no Catholic priests accompanied Castaño

party unlike most expeditions. Perhaps

these Marranos wanted as little to do with the prying eyes of the Church

as possible. Word

had spread of de Sosa's

unauthorized departure. The Virrey of

La Nueva España ordered Capitán

Juan Morlette to gather 40 soldiers and a priest and go in pursuit

of Castaño. He was to

arrest him, by force if necessary, and to affect the release of any

Indian slaves he encountered. Unfortunately,

the details of Morlette's

expedition to Nuevo Méjico are

mostly unknown. It is agreed

that rather than taking the Pecos River

route followed by Castaño, Morlette apparently followed the previous route of Chamuscado/Rodríguez and Espejo down

the Conchos River to its

junction with the Río Grande,

probably at La Junta de los Ríos

and then up the Río Grande to

the Pueblo Indian villages. In

Late-March 1591 C.E., Morlette

and fifty soldiers located the group at Santo

Domingo Pueblo. He

arrested de Sosa and Castaño

without incident. Although Morlette

shackled Castaño, he apparently treated him with respect. After

40 days in which Morlette explored the Pueblo

region for himself, he escorted the party s back southward along the Río

Grande to Méjico. The expedition

was a failure. On

March 5, 1593 C.E., Castaño

de Sosa was convicted of invasion of lands inhabited by peaceful

Indians, raising troops, and entry into the province of Nuevo

Méjico. He was

sentenced to six years of exile in the Philippines and performing such

duties as might be required by the

Gobernador there under penalty of death if he defaulted from his

service. Castaño's

sentence was appealed to the Council of the Indies and eventually

reversed. But it was too

late for him. He would be

killed in the Molucca Islands during the mutiny if Chinese slaves aboard his ship. History

reported that Don Gaspar Castaño

de Sosa and his troop stopped to rest Sixty miles west of Pecos, Nuevo Méjico at

the Pueblo of Jémez. This is where

they were told of a great pueblo

in the mountain pass to the east. In

the language of the Jémez it was called it Pe-kush. The Españoles

heard the word as "Pecos.”

This was to be the future

home of my progenitors, the de

Riberas after 1695 C.E. Sometime after 1590

C.E., Carabajal was arrested for religious heresy and "Judaizing."

By 1595

C.E., the Spanish Inquisition in

La Nueva

España

charged and convicted Carabajal

of heresy, condemning him to six years’ exile from the colony. He

eventually died in prison before being sent away.

His sister and all her family were convicted for Judaizing and

burned at the stake. One of

a Carabajal’s nephews

committed suicide to avoid that fate.

The Inquisition was by then a very active institution in Nueva

España. 1598

C.E. Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá,

Historian, of the Juan Pérez de Oñate

y Salazar Expedition

to first colonized Santa Fé

de Nuevo Méjico Gaspar

Pérez de Villagrá

was one of Juan Ante's

Tenientes and supporters who traveled with the Oñate

expedition into Nuevo Méjico.

He wrote a book entitled,

“A History of Nuevo Méjico

detailing the historical events of the Oñate

Expedition. It was published

in 1610 C.E. preceding the Pilgrims landing in America by ten years. His

book came fourteen years before the publication of Captain John

Smith’s historical book on the events that happened in Virginia during

its colonization. My

Spanish ancestors did not find the legendary cities of gold they sought

and longed for. The sunlight

glistening off flecks of mica in distant adobe walls had fooled them. However,

these early explorers were impacted.

He

would serve as Capitán

and

legal officer under Don Juan Pérez

de Oñate y Salazar. This

was the Expedition that first colonized Santa

Fé

de Nuevo Méjico in 1598

C.E. between 1601 C.E. and 1603 C.E. He

would serve as the alcalde mayor of the Guanacevi

mines in what is now the Mexican state of Durango.

De Villagrá is best known for

his authorship of Historia de la

Nueva México, published in 1610

C.E. Sixteen

years after the 1580 C.E.,

Rodríguez-Sánchez Expedition this party began its trek with de

Villagrá as its official

historian. Four hundred

soldiers departed from the city of Méjico

to head north across the Río

Norte (Río Grande). It was led by Don

Juan Pérez de Oñate y Salazar a strong and determined Español.

It is possible that he

viewed himself as more the conquistador

than colonial official. He

was to eventually be recalled to the city of Méjico

in disgrace. The charges

were neglecting the isolated pobladores, alienating the Indians with his

cruelty, and squandered the resources of el

Imperio Español by searching

for gold, silver, and failing to find them. By

1610 C.E., Pérez de Villagrá published his thirty-four-canto epic poem to chronicle the expedition. He

chronicled its goals, the expedition’s hardships, its courageous

soldiers, the warfare, and its resulting brutality. It

is acclaimed as the first epic poem created by Europeans in North

America. This historical

work about Nuevo Méjico was a

political device, as well as a literary account. It

is suggested that Villagrá's real intended audience was the king of España

and his control of the purse of el

Imperio Español. In

the Villagrá, Historia de la Nueva Méjico, 1610 C.E. translation, the

cantos are rendered in prose. Although

they failed to achieve their immediate goals, these explorers claimed

vast territories for España. This

historical event would define España’s

relationship with the Indigenous of the Southwest and with its European

rivals for the next two centuries. Don

Juan Pérez de Oñate y Salazar Juan de Oñate Expedition The

year, 1998 C.E., marked the cuarto

centenario or 400th year anniversary of the first Spanish settlement

in La Provincia del Nuevo Méjico.

This expedition into the northern borderlands of Nueva España in the Americas was no easy undertaking.

He

was the son of a wealthy conquistador

from Zacatecas, Méjico. De Oñate was born either in 1550

C.E. or 1552 C.E., son of

Don Cristóbal de Oñate, a

wealthy rancher, silver mine developer, and the co-founder of Zacatecas. His mother

was Doña Catalina de Salazar.

Juan

de Oñate was one of the richest men in Zacatecas

because of his family’s silver mines. He

married Isabel de Tolosa Cortés

Moctezuma, the granddaughter

of Hernán Cortés and the

great-granddaughter of Moctezuma.

They had two children, a

son, Cristóbal de Naharriondo Pérez

de Oñate y Cortés Moctezuma and a daughter, María

de Oñate y Cortés Moctezuma. In

1595 C.E., the Virrey awarded the Nuevo Méjico

expedition contract to Don Juan,

scion and soldier. He hoped

to discover new wealth and to enjoy a brilliant future as its Gobernador once officially granted the right to colonize. Here,

it must be stressed that from the outset, the plans plan for

colonization of Nuevo Méjico

included the introduction of not only soldiers to man the presidios,

but also frays building and maintaining Indian missions. There

were also to be hundreds civilian settlers or pobladores

entering the areas in successive waves. There

were many delays in assembling the expedition. However,

by January 1598 C.E., de Oñate

was finally able to get his caravan of eighty-four heavily loaded wagons

and carts carrying baggage and provisions moving. Additionally,

the Expedition managed a large herd of seven thousand head of livestock

sheep, goats, cattle, and horses as they got underway. De

Oñate led one hundred and

twenty-nine men, many with their families and servants, and a small

group of ten Franciscans who joined the party later. My

progenitors, the Varelas and

the Lucero de Godoys, arrived

with the Oñate Expedition in Nuevo Méjico in 1598 C.E.,

founding the northern frontier of La

Nueva España. However,

I shall not discuss those family branches at length due to the

complexity of dealing with each family line other than to list them

later in the body of this chapter. Blazing

a new route scouted by his nephew, Vicente

de Zaldívar, Oñate’s expedition struggled northward from Santa Bárbara along the upper Río

Conchos across the Chihuahuan

desert. Unlike previous

expeditions, this one did not follow the Conchos

to the Río Grande. It

headed straight across the sand dunes of the Chihuahua

desert. A vanguard, after four days without water, reached the Río

Grande on April 20th. Six

days later, the 400 soldiers and others were reunited. In

celebration of its survival a great feast was held. During

their Entrada, while traveling

up the Río del Norte, General Juan de Oñate and

his pobladores encountered a terrain and climate not unlike that of arid

and semi-arid southern España.

In one place, the expedition

suffering from great thirst was providentially saved with a miraculous

downpour so heavy that very large pools were formed and more than seven

thousand head of cattle and mares of all kinds drank. The

exhausted travelers finally reached the Río

Grande and ascended the river. On

Ascending

the river, the expedition crossed it to the east side on May 4th, at a

site just west of present downtown El

Paso. De

Oñate called this operation "El

Paso del Río del Norte," an early use of the name El Paso. Near the upper

reaches of the river he established his headquarters, founded a church,

and formally founded the province of Nuevo

Méjico. Passing

through the narrows near San Felipe

Pueblo, Gobernador de

Oñate arrived at the Pueblo