|

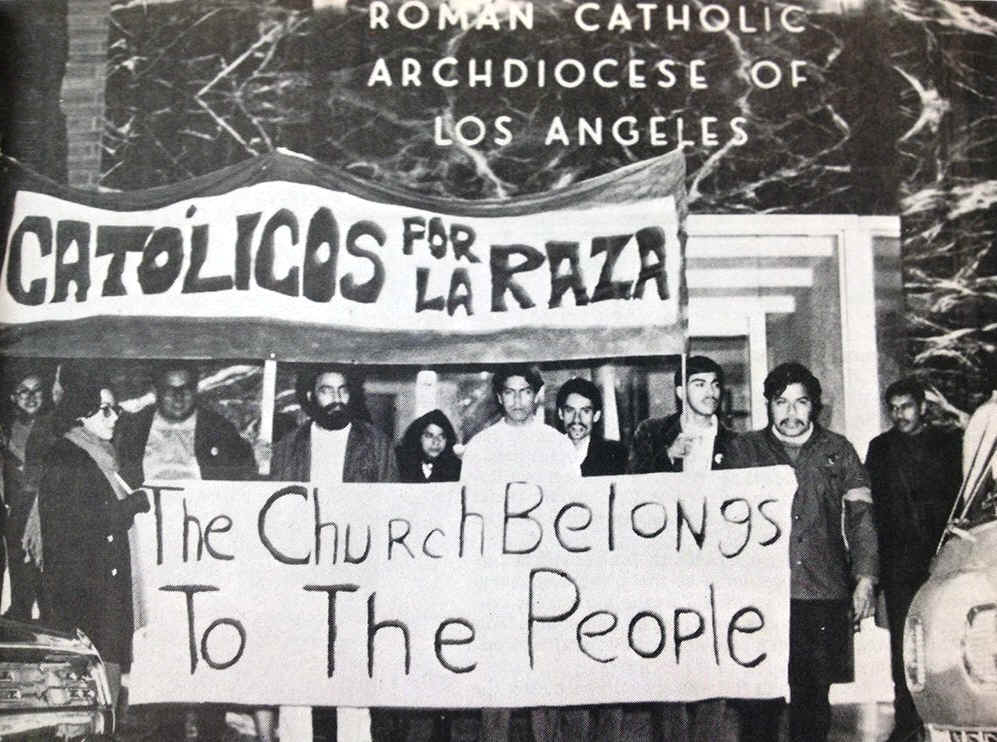

LOS ANGELES (RNS) — Fifty years later, Richard Martínez still remembers

the yelling and screaming. He and a group of supporters of Católicos

por La Raza, a lay Catholic

group, were trying to get into the midnight Mass at St. Basil Catholic

Church in Los Angeles, where then-Cardinal James Francis McIntyre was

presiding. They wanted to confront

McIntyre

about what they said was the Catholic Church’s neglect of the poor and the

lack of Mexican American representation within the institution.

Off-duty

deputy sheriffs, acting as ushers, tried to keep them out. As

Martínez and others tried to force their way in, the crowd outside St.

Basil kept chanting: “Let the poor people in! Let the poor people

in!”

Eventually,

according to Los Angeles Times archives, more than 20 people were

arrested for their part in the melee. "The church needed to

be part of our life," said Martínez, 76. Martínez and other

members of the now disbanded Católicos por La Raza gathered on Saturday

(Jan. 11) at the Church of the Epiphany, an Episcopal church, to

commemorate the famed demonstration. Organizers said the reunion was

important as the group's former members get older.

“We’re

seeing each other only in funerals," said Armando Vazquez-Ramos,

who was 20 at the time of the demonstration. Católicos por La Raza was

formed in 1969 by Mexican Americans who criticized the church for what

they said was a lack of involvement with the farmworker movement led by

Cesar Chavez and the church's lack of support for the Chicano student

walkout movement in Los Angeles. That Christmas Eve, before the clash

with police, between 200 and 350 people gathered outside St. Basil for

an alternative "people's Mass," wrote professor Mario T.

García in his book "Chicano Liberation Theology."

Eventually,

according to Los Angeles Times archives, more than 20 people were

arrested for their part in the melee.

"The

church needed to be part of our life," said Martínez, 76.

Martínez and other members of the now disbanded Católicos por La Raza

gathered on Saturday (Jan. 11) at the Church of the Epiphany, an

Episcopal church, to commemorate the famed demonstration.

Organizers said the reunion was important as the group's former

members get older.

“We’re

seeing each other only in funerals," said Armando Vazquez-Ramos,

who was 20 at the time of the demonstration. Católicos por La Raza was

formed in 1969 by Mexican Americans who criticized the church for what

they said was a lack of involvement with the farmworker movement led by

Cesar Chavez and the church's lack of support for the Chicano student

walkout movement in Los Angeles. That Christmas Eve, before the clash

with police, between 200 and 350 people gathered outside St. Basil for

an alternative "people's Mass," wrote professor Mario T.

García in his book "Chicano Liberation Theology."

The

coalition, which disbanded not long after the Christmas Eve protest, was

part of the larger Chicana and Chicano civil rights movement that

advocated for voting and political rights, educational advancement and

gender equality.

Activists

said they often saw Presbyterian, Baptist and Episcopalian leaders in

the front lines of social justice movements at the time. They wondered,

“Where are the Catholics?” “Mexican-Americans have been most

faithful to Catholicism and its traditions,” read a Católicos news

release addressed to McIntyre.

Católicos

por La Raza leader Richard Cruz detailed the group's objectives

at a news conference at the Los Angeles Press Club, García wrote in his

book.

“We

have committed ourselves to one goal — the return of the Catholic

Church to the oppressed Chicano community,” Cruz announced, saying the

group wanted the Catholic Church “to become as radical as

Christ.” The activism of Católicos por La Raza and the

Christmas Eve

demonstration are not widely known, said Felipe Hinojosa, a professor at

Texas A&M University who focuses on Mexican American studies and

religion. The intersection of religion and politics is an area that has

been sorely understudied in Mexican American history, Hinojosa said.

“This

was the first moment where you had a very bold and brash and unafraid

movement of young people that were going to take on the church,”

Hinojosa said. “Nothing like this had happened, at least not in the

United States.”

Hinojosa

said the church was just another institution “that people within the

Chicano movement went after to try to reform."

St.

Basil's became a focus for protest in the fall of 1969. The church had

cost about $3 million to build, which Católicos por La Raza felt was

too much to spend on

a building.

The

group tried to meet with McIntyre but he refused, according to

García's book. Members picketed the cardinal’s residence at St. Basil

and held a prayer vigil on Thanksgiving, García detailed. Eventually,

on Dec. 18, between 15 and 30 members of the group forced their way into

McIntyre’s office.

McIntyre

was livid, according to García's account. But he listened and

said he’d look into their demands. When Católicos didn’t hear from

him, they proceeded with the Christmas

Eve protests.

A

dozen people were eventually found guilty, with some serving two to four

months in jail for disrupting a religious service, García wrote.

But they believe their actions led to changes in the archdiocese.

McIntyre

announced his retirement in early 1970. Archbishop Timothy Manning took

the helm and soon after met with Católicos por

La Raza, according to García's book. Manning cleared additional

funds for the church’s social and educational services in East LA,

García wrote. The archbishop also created an interparochial

council of clergy for the East LA parishes to function as an advisory

group to him. A year later, the Rev. Juan Arzube, who was originally

from Ecuador, was appointed auxiliary bishop in Los Angeles.

Hinojosa

said the Catholic Church already had a long history of labor organizing,

but it involved certain radical priests or nuns working within the

strictures of the church. After 1969 and 1970, Hinojosa said, “You

have the hierarchy start to say, ‘This is good. Let’s move in this

direction.’ “That was a huge shift,” he said.

Católicos

por La Raza disbanded after anti-Vietnam War, organized

by a group called the Chicano Moratorium Committee

protests,

against the Vietnam War, escalated to violent confrontations with

police. Three people were killed, including journalist Ruben

Salazar.

Lydia

Lopez, on Saturday, vividly remembered those series of events. She

reminisced with dozens of others while they looked over old photos of

their group holding signs that read “The church will be made

relevant” and “Chicanos are also God’s children.”

For

Lopez, it was hard to be critical of the Roman Catholic Church because

she herself was not Catholic. Her husband was, but she was an

Episcopalian.

Lopez

was active in the Chicano movement, and she accompanied her husband on

the night of the demonstration at St. Basil. “I was proud of

that moment even though I’m self-conscious about it because it

wasn’t my pew,” said Lopez, 77.

To

Lopez, the Church of the Epiphany, where the reunion was held, is a

meaningful place. It was the LA base for Chavez, the civil rights

activist, and his farmworker movement and where activists planned the

Chicano Moratorium to protest the Vietnam War draft. She said she was at

a picket line when UCLA professor Juan Gómez-Quiñones invited her to a

party at the church. She went

and remembered seeing the church embellished with papel picado as

mariachis were playing.

“I

wept because I needed a place as a Chicana and I needed a place as a

Christian to call home,” she said. Martínez, who is now

retired, and other former members of Católicos

por La Raza say they hope that Latino churches and young

people can continue some of the Christmas Eve protest, especially at a

time when Hispanic Americans have emerged.

Martínez

went on to work as a professional community organizer. He

worked as a director for the Southwest Voter Registration Education

Project and finished his professional career as an outreach manager with

the county of Los Angeles. “I would hope that the energy, the dynamism

that the Chicano movement had could be reflected in the generations that

are taking on the issues of today,” Martínez said.

Sent:

Friday, January 17, 2020

To: Calderon, Roberto <Roberto.Calderon@unt.edu

|