|

LANGUAGE OPPRESSION AND RESISTANCE:

THE CASE OF MIDDLE CLASS LATINOS IN THE UNITED

STATES

Articulo by Jose A. Cobas

ABSTRACT

The growth of the U.S. Latino population is a source of concern for

many white Americans, who assert this means the death of the U.S. way

of life and the English language. This racialized rhetoric masks an

attempt to maintain the preeminence of the language of the dominant

group over latinos and thus helps whites to sustain their

political-economic domination. Using interviews with 72 middle-class

latinos in seven U.S. states, we document five strategies employed by

the whites in everyday interaction to discourage latinos’ heritage

language use and resistance to such discrimination. Finally, we

discuss ideological elements in U.S. culture that hide the racism in

these language struggles.

LANGUAGE OPPRESSION AND RESISTANCE: U.S. LATINOS

U.S. Latinos have increased steadily and now constitute 13.7

percent of the population (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2004). This

steady growth, ‘the browning of America,’ is viewed with alarm by

many whites, who often view such immigrants as a threat to ‘American

values’ and the U.S. ‘core culture’ (Cornelius 2002).

Language lies within that core, and the dramatic growth of U.S.

Latinos is viewed by many whites as a threat to the survivability of

English, often termed by them ‘the official language of the country.’

As recently as 1987, most people in one national poll thought that the

U.S. Constitution already had made English the official language

(Crawford 1992) and thus they saw no real threat. This benign

perception has changed. For example, the influential Harvard professor

Samuel Huntington (2004), who has served as advisor to government

officials, has articulated strong anti-latino sentiments in his

stereotyped assessment of U.S. immigration. Like many prominent white

officials and executives (Feagin and O' Brien, 2003), Huntington

worries greatly that the United States will become aggressively

bilingual, with English-speaking and Spanish-speaking sectors

incapable of comprehending each other’s languages and values.

OUR CONCEPTUAL APPROACH

When the first English settlers arrived in North America, they saw

themselves as bringing ‘civilization’ to the colonies. ‘Civilization’

meant English language and culture. American Indians, viewed as ‘savages,’

constituted the serious barrier to their plans (Fischer 1989). German

immigrants represented another obstacle; Benjamin Franklin established

a school in Pennsylvania to educate them. Franklin feared these

immigrants could ‘Germanize us instead of us Anglifying them’

(Conklin and Lourie 1983, p. 69).

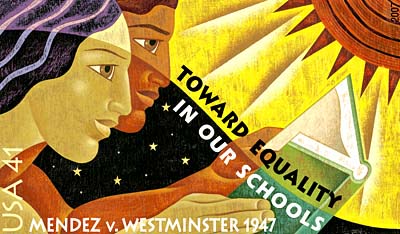

By the mid-nineteenth century the civilized-savage polarity was

replaced by a racist Weltanschauung which played up achievements of

the ‘Anglo-Saxon race’ against the shortcomings of inferior ‘others.’

A common element in both the English-other and the white-other

conceptions was that the dominant group viewed the language of the ‘others’

with suspicion and often sought to eliminate it. In the aftermath of

the 1848 Mexican-American War, the eradication of the Spanish language

became an important U.S. goal. This objective was pursued in the

schools of the Southwest (Gonzalez 1990).

Efforts to squelch the Spanish and other languages persist today.

Since 1986 two dozen U.S. states have enacted similar provisions (Navarrette

2005). Many contemporary Spanish speakers feel in their daily lives

the pressure to give up their mother tongue in favor of English

(Montoya 1998). One might argue that whites’ attempts to limit

latinos from using Spanish do not involve negative racial attitudes.

Yet, this is a difficult position to sustain in light of many negative

stereotypes about Latinos’ language and accents. In whites’

stereotypical accounts, the latino speech is said to reveal low

intelligence and untrustworthiness ( Urciuoli 1999; Santa Ana 2002).

Interference with latino speech occurs regularly, and the interlocutor

is often well educated. Such acts seem to derive from strong emotions

in a country which Silverstein (1996, p. 284) characterizes as having

a ‘culture of monoglot standardization.’

Pierre Bourdieu (1991) identified as socially significant a group’s

linguistic capital (e.g., a prestigious language dialect). The

linguistic capital of Parisian French is higher than that of French in

the countryside. According to Bourdieu (1979, p. 652 ), when

individuals are in the linguistic market, the price of their speech

depends on the status of the speaker. The outcome of linguistic

exchange is contingent on the speaker’s choice of language, such as

in situations of bilingualism, when one of the languages has a lower

status. A group can strive for advantage in the linguistic market in

order to bring about political and material gains. One way to achieve

this end is by promoting the language it commands. Yet, the efforts of

a group to achieve linguistic dominance is often met with resistance (Bourdieu,

1991, pp. 95-6). Although some classes, as the members of the

bourgeoisie in post-Revolution France, operate from an advantageous

position, the linguistic ascendancy of a class is the result of a

struggle in the language market that is seldom permanently resolved.

Achievement of language dominance does not necessarily mean that other

languages disappear. Nonetheless, the dominant language becomes ‘the

norm against which the (linguistic) prices of the other modes of

expression… are defined’ (Bourdieu 1977, p. 652). Drawing in part

on these ideas, we view white efforts to delimit or suppress Spanish

as a thrust to protect or enhance the reach and power of English

speakers vis-à-vis Spanish speakers.

The mechanisms used by U.S. economic and political elites to

establish English ascendancy over Spanish vary, as we will

demonstrate. Language subordination of latinos in the United States

includes the idea that English is superior to Spanish (Santa Ana

2002). A second method is the denigration of Spanish-accented English.

Other foreign accents are not judged in the same harsh terms (Lippi-Green

1997, pp. 238-39): ‘It is crucial to remember that not all foreign

accents, but only accent linked to skin that isn’t white, or which

signals a third-world homeland, that evokes… negative reactions.

There are no documented cases of native speakers of Swedish or Dutch

or Gaelic being turned away from jobs because of communicative

difficulties, although these adult speakers face the same challenge as

native speakers of Spanish.’

Another form of language denigration is ignoring speakers of

Spanish even when they have a command of English. They are ignored by

some whites as groups of people not worth listening to, as if their

knowledge of their mother tongue renders their message meaningless and

undeserving of attention (Lippi-Green 1997, p. 201). The process of

linguistic denigration of non-whites also includes another component:

the expression of skepticism or surprise when people of color evidence

command of standard English. It is as if non-whites’ linguistic

abilities were so contaminated that when they show their abilities in

writing or speaking unaccented English some whites are unprepared to

believe what they see (Essed 1991, p. 202).

Oppressed groups typically defend to the best of their ability

against efforts to denigrate their languages or erect barriers against

their use. Some examples are the Basque, Catalan, Occitan, and Bosnian

peoples (Shafir 1995; Siguan 2002; Wood 2005). Cultural groups

struggle to keep their language because it is fundamental to social

life and expresses the understandings of its associated culture in

overt and subtle ways (Fishman 1989, p. 470). Many latinos prefer to

use Spanish because it affords them a richer form of communication.

Other U.S. racial groups struggle to protect their languages (cf.

Horton 1995, p. 211).

Although latinos are disadvantaged in the language market, because

of the power of whites, they often resist attempts to squelch their

language. When told to stop speaking Spanish on the grounds that

Spanish is out of place, latinos often respond by asserting the

legitimacy of their mother tongue. At a deeper level, this may be seen

as a disagreement in which the white side is trying to disparage

latinos’ language and latinos’ efforts to counter that image. In

other instances, the latino individual persists against prohibitions

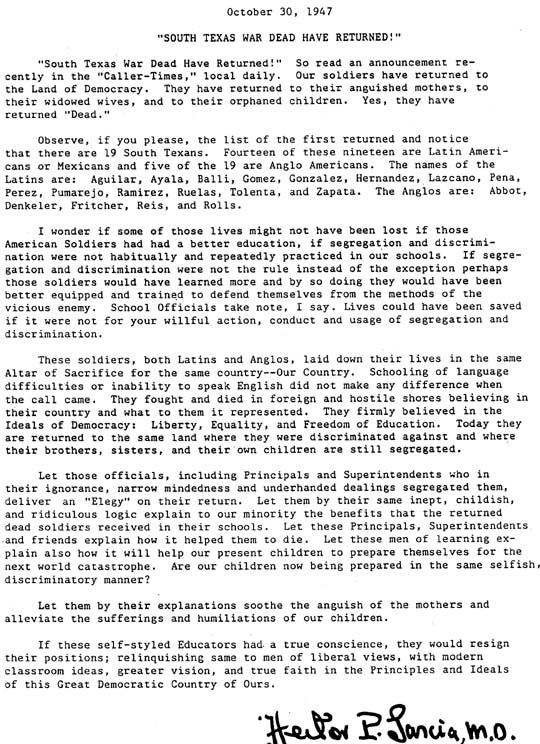

that he or she speak Spanish through different means. In a celebrated

U.S. court case, Héctor García was employed as a salesperson by

Gloor Lumber and Supply, Inc., of Amarillo, Texas. Gloor Lumber

allowed its employees to communicate in Spanish on the job only if

there were Spanish-speaking customers. García broke company policy by

speaking Spanish with latino coworkers. He was fired, sued and lost

(Gonzalez 2000). García insisted on his right to speak

Spanish.

In this article, we demonstrate a number of different techniques

that are perceived by our subjects as attempts by whites to undermine

the status of Spanish and Spanish speakers and discourage the language’s

everyday use. We also examine forms of latino resistance to this

linguistic restriction and oppression.

OUR DATA

In this exploratory analysis of linguistic

barriers and resistance, we employ new data from 72 in-depth

interviews of mostly middle-class latinos carried out in 2003-2005 in

numerous states with substantial latino populations.

For this pioneering research (the first of its kind, so far as we

can tell), we intentionally chose middle-class respondents for two

reasons. First, they are the ones most likely to have substantial

contacts with white Americans in their daily rounds, and are thus more

likely to encounter racial barriers from whites and to feel the

greatest pressures to give up language and cultural heritage.

Secondly, they are the ones who are considered, especially by the

white-controlled mass media and by middle-class white Americans

generally, to be the most successful members of their group – and

thus to face little discrimination in what is presented as a nonracist

United States. Thus, since social scientist Nathan Glazer’s 1975

book, Affirmative Discrimination, was published, a great many U.S.

scholars have argued that there is little or no racial discrimination

left in U.S. society and that, in particular, middle-class people of

color face no significant racial or ethnic barriers. The first

extensive qualitative fieldwork on the life experiences of

contemporary African Americans--conducted in the late 1980s and early

1990s--took this approach, and in this research project we have

followed much of the rationale and research guidelines for that

prize-winning research (Essed 1991; Feagin and Sikes 1994; Feagin,

Vera, and Imani 1996).

In this innovative research we intentionally focus on those latinos

generally considered middle class and economically successful, such as

teachers, small business owners, office workers, and mid-level

government administrators. More than 90 percent of the respondents

have at least some college work, and 58 percent have completed at

least a college degree. A small minority hold clerical or manual jobs.

Using the qualitative methods of researchers studying everyday racial

experiences (Essed 1991; Feagin and Sikes 1994), we used a carefully

crafted snowball sampling design and used more than two dozen

different starting points in seven states to insure diversity in the

sample. Initial respondents were referred by colleagues across the

country. As we proceeded, participants suggested others for

interviews. Few respondents are part of the same networks as others in

the sample.

The respondents are mainly from the key latino states of Arizona,

California, Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, New York and Texas. Sixty

percent of our respondents are Mexican-American; 18 percent are

Cuban-American; 13 percent are Puerto Rican; and the remaining 9

percent are other from Latin American countries. This distribution is

roughly similar to that of the U.S. latino population. Sixty-four

percent of the respondents are women, and 36 percent are men.

LANGUAGE CONTROL stratagemS AND RESISTANCE RESPONSES

We examine relationships between whites, the most powerful U.S.

racial group, and latinos, a group that whites usually define racially

as "not white" (Feagin and Dirks 2006). One reason for this

focus is their central importance for the position of latinos in U.S.

society. Another is that there are very few accounts in our latino

interviews of other Americans of color attempting to discriminate

latino respondents on language grounds. One reason for this, we

venture, is that non-latino people of color are usually not in

position to complain loudly about Spanish language even if they wished

to, because they do have significant power in U.S. institutions.

As we observe below, even those whites not in the middle class, as

much recent research has demonstrated (see Feagin and Sikes 1994),

feel great power as whites to assert the privileges of whiteness

versus people of color. As we will observe constantly in our accounts,

Anglo whites in the upper middle, middle, and working classes feel

powerful over middle-class latinos. In most accounts, the whites

discriminators are of equal or higher socioeconomic status than those

latinos targeted for discrimination.

The common goal in the language control methods of whites is to

disparage the language of latinos. The methods follow a variety of

strategies. Some are aimed at latinos’ use of English: asking

participants to stop speaking Spanish, because ‘English’ is the

language of the land or because the white interlocutors want to know

‘what’s going on,’ and ignoring latinos who speak Spanish. Other

forms of control are deriding latinos’ accents, raising questions

about their proficiency in English when Latinos demonstrate skill.

Whites define latino speech as tainted in two senses. First, when

latinos speak Spanish they are using a language that ‘does not

belong’ in the United States and may be saying things behind whites’

backs. Second, when they speak English, their accent is inferior and

does not belong. Whites see themselves as the authorities to

adjudicate language use. Attempts to control latinos’ language or

disparage it often provoke responses from the latinos involved in the

interaction or witnessing it. The discussion that follows is organized

around the different types of language control and denigration

stratagems.

Silencing Spanish Speakers

One language control strategy is ‘silencing.’ It is the

stratagem most frequently mentioned by the respondents. Silencing is

straightforward: It consists of a command from members of the white

group to latinos to stop speaking Spanish. It carries the supposition

that whites can interfere in Spanish conversations of latinos to stop

them from speaking Spanish. The command is usually based on the

explicit or implied assumption by the interlocutor that, ‘We only

speak English in America.’

A Cuban-American attorney remembers this story from her childhood a

few decades back. It shows a classic case of silencing:

We were in (a supermarket)…. It was during the Mariel

Boatlift situation … there was a whole bunch of negative

media out towards Cubans ‘cause … many of the people that

were coming over were ex-cons or what-not… And so my mother

was speaking to us in Spanish … and this (white) woman

passed by my mother and said… ‘Speak English, you stupid

Cuban!’ .… And then my mother turned around, and

purposefully, in broken English, because she speaks pretty

good English… said, ‘I beg your pardon?’… (The woman)

repeated the statement.

The Cuban interlocutor’s response is quite assertive:

And my mother… asked her if she was a native American

Indian. And when the lady responded ‘No… I’m Polish,’

… my mother responded … ‘Well, you’re a stupid

refugee just like me.…’ And, the lady, I don’t know what

she said, but my mother said, ‘Do you know why I’m here,

in this country?... I’m here (which was not true) because I

just came in the …( Mariel Boatlift) and the reason…was

because I killed two in Cuba, (and) one more here will make no

difference.’ …And so then (the woman) thought my mom was

being serious and left there really quickly.

When she asks the white interlocutor, who is likely a middle class

shopper, about her Indian ancestry, the respondent reposts by saying

in essence that she and her language are as American as the white

Polish woman’s.

In the next account, the attempt at silencing is indirect. A white

Anglo post office employee, who is likely working class or lower

middle class, complains to the postmaster, a latino, that two fellow

workers are speaking Spanish on the job, and asks the boss to make

them stop. The postmaster refuses to comply:

I had that situation when I was working for the post

office. I had two Chicanos that were talking in Spanish. There

was an Anglo carrier right in the middle and she approached me

and told me that I should keep them from speaking Spanish. I

said, ‘You know both of them are Vietnam veterans and I

think that they fought for the right to talk any language they

want to.’

The postmaster’s response attributes legitimacy to the latino’s

speaking any language they choose because they are veterans who fought

in Vietnam and are Americans entitled to any language they please.

A latino respondent in a southwestern city was trying to help a

Mexican immigrant at a convenience store. Their conversation was in

Spanish. As they talked, a white interlocutor interrupted and voiced

his displeasure at their use of Spanish, first by the indirect means

of complaining about the supposed loudness and then more directly by

suggesting the immigrant should leave the country.

(This) farm worker…. is Mexican. I was speaking to him

(in Spanish)…. and this (white) individual asked us if I had

to speak so loud. ‘Can you guys lower your voice?’...

[Were you guys talking out in the street?] ‘No, there is a

Circle K right by (work). We were standing right by (the

counter)’.... [Did you respond to this man?] ‘I very

politely explained to him and he was shocked (at the quality

of my English) when I looked at him and I said, pardon me sir,

I am speaking to him in Spanish … because he doesn’t speak

English.’ His response then was, ‘maybe he should move out’.

I said to him … ‘if he moves out, then why don’t you go

pick the stuff out in the field?’ [What did he say to that?]

‘He just turned around and walked away.’

The response from someone who may have been a fellow shopper says,

in essence, that the Mexican immigrant is performing a useful function

in the United States, doing necessary work that the white interlocutor

and many other whites apparently are not willing to do. At the very

least, the respondent appears to say, he has a right to communicate in

his mother tongue.

In the next episode, a successful executive related an incident

that happened when he was on vacation with his family and visiting a

famous amusement park. He and his wife came to the United States at an

early age, and they have an advanced English proficiency. Yet they

decided to often speak to their children in Spanish while they were

young, so that they would learn the Spanish language. He provided this

account:

‘I had a really bad experience at Disneyworld… My son

at the time was … three .… He jumped the line and went

straight to where there was Pluto or Mickey Mouse or something

and I said, (Son’s name), come back,’ in Spanish and …

ran after him. And I heard behind me somebody say, ‘It would

be a ------- spic that would cut the line.’ Now my wife saw

who said it, and I said, ‘Who said that?’ in English and

nobody said a word. And I said (to my wife), ‘Point him out,

I want to know who said that,’ and she refused. I was like,

‘Who was the ------------ who said that?’ I said, ‘Be

brave enough to say it to my face because I’m going to kill

you.’ You can see me, I’m 6’3’, 275 (pounds). Nobody

volunteered’.…[So nobody stepped up?] ‘No, no and there

was a bunch of guys there, and I would have thrown down two or

three of them; I wouldn’t have had a problem.’

The executive’s response was clear, to the point, and came from

the heart: his child was insulted by (probably middle class) white

visitors to this expensive theme park. He was deeply offended for his

family. Clearly his strong reaction could have led to further serious

consequences, yet he was willing to take this risk by responding

aggressively to the ultimate racist slur for latinos.

In these accounts, whites who are attacking or discriminating vary

in social status. Sometimes, they are of higher socioeconomic status

than our respondents, and at other times they are of equal or lower

status. Yet, all whites seem to feel the power to hurl racist

commentaries at latinos who are attempting to live out normal lives.

Practices silencing Spanish speakers reveal the asymmetric statuses

of the English and Spanish languages. It would be inconceivable for a

latino to ask a white Anglo to stop speaking English in any Latino

neighborhood. Such reciprocity in action would suggest a language

equality that does not exist, and latinos are well aware of this

societal situation. We asked a South American respondent the following

question, ‘Sometimes … I ask people I interview... have you ever

seen a Mexican at a grocery store turn to [white person] and say, ‘Please

do not speak English? Have you seen this happen?’ She laughed, ‘No,

no!’

Despite attempts at the imposition of barriers, Spanish speaking

respondents frequently answer back, softly or aggressively, thereby

insisting on their right to use their native language.

Voicing Suspicion: Fears of Spanish-Speaking Americans

In the everyday worlds of latinos, whites' language-suspicion

actions differ from language silencing acts in that the latter emanate

from a conviction that English is the only acceptable language in the

United States. Language-suspicion actions generally involve less

confrontation.

Whereas silencing actions derive from a strongly-held notion about

what should be the dominant language, suspicion actions likely reveal

a notion that Spanish speakers need to be watched, that they are

perfidious or sneaky (Urciuoli 1996). Silencing draws from a type of

an ethnocentric discourse, one that goes back to 18th

century Anglo-American fears of German immigrants and their language (Feagin

1997, p. 18). The suspicion response is rooted in anti-latino

stereotypes. There is a common substratum of racialized thinking: When

latinos speak Spanish, they are not playing by the ‘right’ rules

as envisioned and asserted by whites. White interlocutors assume a

right to interfere in a Spanish language interaction to put an end to

it or at least alter it.

A major difference between silencing and voicing suspicion is that

some of the white interlocutors who object to Spanish on the grounds

that they are excluded express, at least on the surface, a desire to

be included in the interaction. This inclusion is, however, one that

is seen and defined in white terms, for the conversation must be in

the white person’s language.

Another respondent provided an example of suspiciousness on the

part of a more senior white manager who did not want her workers

speaking Spanish:

‘Most of the coworkers and the supervisors or managers

are bilingual… but… my manager was only unilingual.… She

does not understand … that we were not talking about her…We

were talking about our business… and personal stuff, but she

doesn’t have to know what we were talking because we don’t

need for her to give us her … point of view. If we need for

her to talk we are going to ask her in English, not in Spanish….

(She said) ‘I don’t want you speaking Spanish’ and I

told her ‘I do not agree with you because this is not right’.

[And what did she say?] She said ‘Well, it’s not right; it

doesn’t matter’. And I said, ‘Yes, it does matter and

you’re not going to stop me from speaking my first language.’

The interviewee’s response is an unequivocal statement about her

right to speak her first language. It resonates with the theme so

frequently seen in the ripostes given by other respondents: ‘I’m

entitled to speak my language.’

A male respondent reported on a situation where he was speaking in

Spanish with another latino in a bank, when a white stranger broke

into their private conversation:

‘On one occasion we were at a Bank of … branch… We

were talking (in Spanish) and all of a sudden this (white)

lady comes and asks us (in English) what we were talking

about. [What did you reply?] We told her we were talking about

our business.

Although we do not know what the white woman in this affluent

setting had in mind when she interfered in the conversation, her

action suggests the recurring concern of many whites that those not

speaking in English may be plotting something contrary to white

interests. There is no doubt that she took it for granted that she was

entitled to interrupt. The latino’s response is matter-of-fact and

seems to convey the notion that in his mind what he and his friend

were doing was legitimate.

Another respondent reported that she was hired to work at a store

in a U.S. town near the Mexican border so that she could help the

numerous Spanish-speaking customers who crossed from Mexico to go to

the store. Yet she faced a significant problem when she tried to do

her job: she could not speak to customers in Spanish if white

customers were present. It seems that the store owners were less

concerned with causing difficulties for their Mexican customers than

with offending the white ones:

In a store where I worked… I (saw a) lot of

discrimination (against) the people that were coming from

across the line (frontier) to shop here… If I (spoke)

English (to them) they’d feel discriminated because they

couldn’t understand me. Or if I spoke Spanish and there was

an English patron shopping they’d feel that I was speaking

against them or saying something that I should not be saying

and I should be speaking (English) … How could I do this

when I had English speaking people and Spanish speaking people

but the one I was directly addressing was Spanish speaking and

a non-English speaking person? Yet I was felt made to feel

that I should be speaking English because I was in America.

Even though she was upset at the unreasonable situation in which

she was placed, there was little the respondent could do short of

quitting her job.

Another respondent, a female manager in a public agency, was also

asked if ‘Anglo whites ever object to your speaking Spanish at work?’

She replied:

Yes. They are like, could you please speak English because

we don’t understand what you are saying.… Even the

supervisor tells us sometimes that we should talk in English

because there are some people that don’t know Spanish. But

you know what, I feel better speaking Spanish … because that’s

my primary language. There is a lady that actually, that’s

always complaining…. There are times that … she just feels

like left out of the conversation. She’s like, I want to

know what’s going on, but there are times that she’s kind

of rude, so. [How do you usually respond to her?] I’m like,

well, you need to learn Spanish.

The middle class respondent asserted the legitimacy of her Spanish

use in a different form by suggesting that those fellow workers,

middle class whites here, who wanted to partake in her

Spanish-language conversations learn Spanish. Such a request may seem

ludicrous only if one believes that English is the only language worth

speaking in the United States. Even when languages have is granted

official status, individuals are not forbidden to use other tongues in

settings like work.

Suspicion of latinos speaking Spanish constitutes another instance

of attempts on the part of whites to regulate latinos’ speech. In

this instance, the reason given is that whites feel that Latinos are

talking about them. The justification for white attempts reveals a

view of Spanish speakers as sneaky and untrustworthy and the view that

whites should be included in interactions with Latinos on the white’s

terms. Despite whites’ objections, the typical Latino responds by

asserting his/her right to use their mother tongue.

Doubting English Proficiency of Latinos

Since anti-latino rhetoric places such a heavy emphasis on Latinos’

abandoning their heritage language, one would expect that when Latinos

venture into the world of English they would receive encouragement

from whites. This is often not the case. There is white obstinacy

here: latinos speak Spanish, an inferior language, and thus they are

apparently presumed to be tainted by their heritage language when they

speak or write English, even when there is evidence to the contrary.

In some cases, their English is assumed to be ‘too perfect’

(compare Essed 1991, p. 202).

One example comes from the college experience of a chicana

professional. She was born in a mining town in the Southwest, and her

English did not have the accent many whites consider undesirable. She

reported on an instructor who questioned her integrity:

(A professor) in college refused to believe that I had

written an essay… because she assumed that Mexicans don’t

write very well and so therefore I couldn’t have written

this paper. [Did she tell you that?] Yes she did.… And so

she asked that I write it over again…[So what did you do?] I

rewrote the assignment and she still didn’t believe that it

was my own .… She still refused to believe that it was my

handwriting or my writing because she still felt that Mexicans

could not express themselves well in English . . .

[Did she use those words?] Yes she did.

This woman explained that she came from a mining town where labor

unions had helped Mexicans gain access to schools, so she had good

English skills. The well-educated white instructor felt substantial

power to impose her views: Mexicans cannot express themselves well in

English. We see here an active countering response. The respondent

stood up to the instructor but was unable to change her mind. Here

again, we observe whites of higher social status or in more powerful

positions discriminating against our latino respondents.

Another latina had a different experience. Asked whether whites

have ever acted rudely after they heard her Spanish accent, she

answered in the negative and discussed ‘left-handed compliments’

she receives:

No. In fact people go out of their way to tell me that I

don’t have an accent. [Is that a compliment?]. I think so….[Tell

me in more detail].Well you know, they begin to ask me, well

where are you from? Am I from Arizona? No I am not from

Arizona…. I’m from Texas. And then their comment is that

you don’t have an accent. And I’m like what kind of accent

are you talking about? I don’t have a Texas accent, the

twang. And then I’ll say, no and I don’t have a Spanish

accent. I speak both languages. And they are like, well wow,

you don’t have an accent. Never fails….

White interlocutors in her immediate environment express surprise

at her apparently unaccented English. The astonishment expressed by

whites is reflective of stereotypes concerning some latinos’ English

proficiency. In such settings, whites assume they have the

right to determine which accented dialect of English is prized.

English has many dialects, all with distinctive accents, yet most U.S.

whites (unlike many European whites) are monolingual and do not view

their own prized versions of English as accented.

In the next excerpt, a woman from Latin America relates her

experiences with a paper she wrote. She had problems with contractions

in English and had her paper checked by a campus facility that helped

students. The center’s staff found no mistakes. Nonetheless, the

latina’s highly educated white male instructor did not approve of

how she used contractions, and even though he did not take off points

from her grade, he made some comments to the class about foreign

students:

I wrote a paper and I used some contractions and most of

the time I have some problems with contractions…. I took my

paper to the English writing center and nobody corrected

anything. And so when I got my paper back (from the [white]

instructor) and all the contractions were corrected and so I

didn’t say anything, but I took the paper back (to the

writing center) and they explained to me that there was not

any specific reason to have changed them… [Did you get a bad

grade on the paper?] No, but the teacher made a comment in

class about foreign students and that we were in graduate

school and we should write free of mistakes…. I said to

myself that if I had been an American student using these

words he would not have changed it…. It was because there

was nothing else to correct on the paper. [He just was looking

for something to correct, that’s what you are saying?] Yes.

This respondent did not confront her middle-class instructor

directly, but in going back to the writing center, she refused to

accept the definition of her abilities that he attempted to impose on

her and expressed her anger at the language-linked discrimination (on

a similar problem for African Americans, see Essed 1991, p. 232).

Intended or not, whites’ skepticism toward latinos’

demonstrated proficiency in English is part of the denigration of

latinos. Although it is not a direct attack on Spanish, it reflects

notions of language deficiency among the mass of latinos--based,

ironically, on the deviation of latino interlocutors from

stereotypical expectations.

Denigrating the Accent

Another method of undervaluing latinos’ English proficiency is by

mocking those who have an accent whites consider undesirable. When

they speak English, latinos frequently experience a close monitoring

by whites, and if some sign of a certain accent is detected, they risk

ridicule. In business or government settings white customers sometimes

even refuse to deal with latino personnel because their accent is

¨not American.’ Indeed, some latinos feel so self-conscious that

speaking English becomes difficult (Hill 1999).

Consider this account from a highly educated latino who went to a

computer store. In response to our question, ‘has a white Anglo . .

. acted abruptly after he heard your accent?’ he replied:

Oh, that has happened several times. I have had owners of

a store imitate my accent. [To your face?] In my face, yeah. I

went to buy a printer… I said, I’m here to buy a printer

and the owner imitated my accent, back…. [Did you buy the

printer?] No, I did not. … I felt that I was growing red in

the face… And I said, ‘You know what, just forget it I’ll

buy it somewhere else,’ and I turned around and left.

Something as simple as buying a printer turned into a humiliating,

in this case from upper middle-class whites. Having the experience of

someone powerful imitating his accent was not an isolated instance.

Indeed, we see in several respondents' quotes this cumulative reality

of discrimination; many forms of discrimination take place on a

recurring basis in the lives of latinos. In refusing to purchase, the

respondent resisted the discrimination and registered displeasure.

Another middle-class Latino who works at the customer service

department of a retail store gave this example:

There was one time that I answered (the telephone) at my

work currently, I had this lady, … and she goes, ‘I don’t

want to talk to you, you have an accent!’ I was like, ‘you

don’t want to talk to me?’ she goes, ‘Yeah, I want to

talk to an American.’ I was like ‘ok. We’ll I’m sorry

you’re gonna have to redial to speak to someone that you

want.’ She goes, ‘well go ahead and transfer me over.’ I

was like, ‘I’m sorry, I’m not going to be able to

transfer you over. I have to take the call. I’m here to help

you if you need anything.’ She goes, ‘well I don’t

understand you. And I just kept going, well I there’s

anything I can do for you, I’m here.’ So she finally gave

me her number and we went over the account and at the end she

goes, ‘I’m really sorry that I was too rude to you at the

beginning.’

The white caller assumed that the individual answering the

telephone could not be ‘an American’ because she had a Spanish

accent and went on to say that she wanted to deal with ‘an American,’

suggesting that the Latina could not offer the same level of service.

The Latina insisted that she was able to help and the white shopper at

the end gave the service representative a chance to help her.

A South American doctor, who works as a medical assistant while she

attempts to validate her medical credentials in the United States,

told us about her problems when dealing with patients. One in

particular was very rude:

There is a white female patient who has not come out and said it,

but lets me know that my accent bothers her…. I called

another patient, an elderly woman who was a little ways from

me, and she did not hear me. The first patient, in a rather

aggressive way, said to me, ‘Who is going to understand you

with that accent of yours?’ [What did you say?] I called the

elderly patient again …. [Do you prefer to remain quiet?] I

don’t like to get in trouble over things that don’t matter

that much.

This white patient took it upon herself to intervene where it did

not concern her and used the opportunity to make a scornful comment,

which served no purpose other than to demean the doctor’s accent.

Note again the repertoire of responses. Here the Latina did not

respond aggressively, but dismissed the patient’s behavior and kept

her professional demeanor.

For another woman, her accent was a cause of discomfort while

dealing with white clerks. She replied to the question, has ‘a white

Anglo store clerk acted abruptly after he heard your accent?’ this

way:

All the time.... They tend to say, ‘What?’ And in a

rude way.... Always it is this ‘What?’ .… Yes, it is

never ‘Oh, I am sorry I couldn’t hear you’…. They are

gesticulating… this non-verbal behavior that is telling you

… ‘who are you’ or ‘I can’t understand you’ or ‘Why

are you even here?’ … you get all these messages… (they

are all) very negative.

This respondent’s accent evoked unwelcoming behavior from whites

who may have been of lower social status than the respondent. In many

instances, as we have seen the whites who discriminate are of equal or

higher status than the respondents. In other settings, there are of

lower status, yet most whites in either status seem to feel the power

to discriminate in this fashion. The respondent clearly felt that the

legitimacy of her status in the country was being questioned. We see

here the way in which language attacks can literally crash into a

person's everyday life when least expected.

Language mocking can affect a person’s emotions, as the next

account illustrates. The perpetrator of an attack was a dear friend

who evidently thought she was just joking:

[Anybody ever approach you about your accent?] ‘Yeah, all

the time, all the time….I had a very… bad experience with

somebody love very much. I was in…in nursing school and I

had this friend and we’re very, very close. I mean we went

through the nursing school together and we were great friends

and I adored my friend, but she would always make fun of my

accent. Because there’s still a lot of words, I still can’t

say some words, a few words. She would always make fun of

either the way the word sounded or whatever and I would never

say anything because that’s the type of person I am. I just

take everything in and I don’t verbalize my feelings most of

the time. But that’s me. So when we were graduating from the

program I wrote her a letter and I told her that I loved her

very much and I wanted to continue to be her friend, but that

if my accent bothered her that much that it was ok with me not

to be friends anymore. And that I felt very uncomfortable with

the way she criticized me with my accent’. [She was a non-latino?]….

‘She was Italian.’

The latina’s educated Italian American friend evidently did not

know the pain her mocking was inflicting. Our respondent endured the

pain as long as she could, but eventually decided that if taking the

mocking was the price of the friendship, she could dispense with it.

She was gentle, but stood up for herself.

In her interview a Mexican American with a master’s degree

sounded apologetic about being U.S.-born yet possibly having an ‘accent.’

She noted that some white middle-class co-workers had been supportive,

but others had made fun of her:

English is my first language, so I really don’t know if I

have an accent, but there are sometimes where some words come

out different and that does get recognized by some people that

I work with. And I don’t think it’s an intentional making

fun of (it), but it’s noticeable and you know they kind of

make a slight joke off of it. But I’d have to say I work

around both types of people, (some) that have been really

supportive despite some other people which you know they

really look at you as not knowing as much (as whites).

Self-consciousness about a certain Spanish-linked accent is common

among latinos (Urciuoli 1996), including those who are U.S.-born. In a

related vain, Bourdieu (1991, p. 77) discusses the ‘self-censorship’

experienced by speakers who anticipate a low price for their speech in

the linguistic market. This causes a certain demeanor (tension,

embarrassment) which reinforces the market’s verdict.

The denigration of Spanish and Spanish accents, whether in joking

or more serious commentaries, is generally insidious and thus part of

the social ‘woodwork’ in the United States. In contrast, whites

rarely denigrate the many accents of fellow white English speakers in

such routine and caustic ways.

Most of our respondents resist through an array of strategies. At

work sometimes they refuse to go along with demands that they not

speak Spanish. There are other instances, such as when they work with

the public, when the targets of mocking are in no position to resist.

In other circumstances, as when they are customers in a store, they

can express their displeasure at the way they are being treated, such

as by discontinuing their shopping.

Ignoring Spanish Speakers

Many latinos report that whites dismiss them as not being worthy of

attention after hearing them speaking Spanish. Unlike silencing,

deriding Spanish accents , or voicing suspicion, ignoring Spanish

speakers is a passive form of expressing disapproval toward the use of

Spanish.

The case reported by the following interviewee occurred at a

high-end resort in Arizona. She and her family went for drinks:

[In the last five years have you been mistreated in

restaurants by whites because of your race, ethnicity,

speaking Spanish or accent?] Yeah, we went to (resort

restaurant) and we tried to order some drinks, but the lady

kept passing and passing and said that she would come, but

never came to ask what we want to drink I think because she

heard us speaking Spanish….[And was the server, the person

white?] She was white and we told her, we called her and told

her if she wasn’t going to take our order or what because

why that discrimination? We asked her a few times to come

nicely and she kept saying, ‘I will be back, I will be back’

and so she apologized and excused herself of course ‘cause

if not we were going to make a problem. [Then you told her

that you felt discriminated?] Yeah. [And you say ‘we’,

with whom were you at the hotel?] My mom and her husband and

other friends.[ And you were speaking Spanish?] Yeah. [And so

the lady then came and?] And she kind of apologized and we

said ‘if not we want to talk to your managers’. [Did she

change her attitude?] Yeah.

After repeated attempts, the respondent and family members said

they felt discriminated against, and it appears that this caused the

white server to change her attitude. In this case, the white person

was clearly of lower social status than the latino family members, yet

still felt she could discriminate in the provision of service.

CONCLUSION

The so-called ‘browning of America’ has raised fears among many

whites at all class levels. The reason typically given is that latinos

represent a threat to the U.S. way of life, with the English language

as a major symbol of that way of life. Many whites have responded in

part by racializing latinos and their language and attempting to

demean its importance.

Efforts at squelching Spanish at an interpersonal level take

various forms: Outright commands to Spanish speakers to speak English,

protestations that when they speak Spanish latinos are talking about

whites, skepticism about English proficiency of Latinos despite

evidence to the contrary, mocking Latinos’ ‘accents,’ and

ignoring Spanish speakers. Latinos often resist these incursions into

their heritage language, but their resources are usually limited when

compared to those at the disposal of most of their white antagonists.

Latinos often resist this mistreatment--a formidable task in light

of the white establishment’s resources. Today, Spanish is ridiculed

by influential whites, who often call for much stricter government

control over Latin American immigrants. Ideological elements emanating

from the dominant culture may mask for some Latinos the structural

basis of their victimization and thus interfere with their ability to

see the systemic structure of their oppression, yet there are no signs

of surrender to whites' anti-latino discrimination.

The xenophobic discourse aimed at latinos relies heavily on the

notion that they and their culture are sounding the death knell for

English culture. This white discourse is heavy in rhetoric and short

on evidence. Indeed, many English language programs for immigrants

have long waiting lists. Facility in multiple languages is a valuable

cultural resource for U.S. society. There is a widespread belief among

our study’s respondents that there should be more tolerance toward

languages other than English. Asked about attempts to ban Spanish in

U.S. society, one respondent’s answer was typical:

I think the more languages you speak, the more culture you

have, the more educated you are. We’re in a global society,

I mean Spanish is the number two spoken language of the

Americas. [Is it ok with you to use Spanish in ballots or

other official documents?] You know this is the United States

and English should be the number one language but, if they are

U.S. citizens and they are paying U.S. taxes, then they should

have Spanish ballots.

Interestingly, not one of our seventy-two respondents argued that

language tolerance should be limited only to Spanish. Not one

advocated that Spanish should replace English as the language inside

or outside latino communities. Analysts like Huntington (2004) accuse

latinos of being a threat to democracy and the ‘American way of

life,’ which for them means Anglo-Saxon ways of doing things. On

close examination, this is a peculiar accusation because most latinos

are accenting the virtues of language and other cultural diversity

that the official U.S. ideology accents in its omnipresent ‘melting

pot’ imagery.

The struggles between Latinos and whites over language do not take

place on a level playing field. As Barth (1969, p. 31) has put it, the

interaction between the majority group and the minority group ‘takes

place entirely within the framework of the dominant, majority group’s

statuses and institutions.’ Given their position in the racial

hierarchy of U.S. society, whites have tremendous resources at their

disposal in the worlds of politics, business, finance, mass media, and

education. Powerful white elites control much of the normative

structure (Gramsci 1988), as well as much of the dominant thinking

about what is right and proper in society. In this white-dominated

milieu, Latinos struggle to preserve their heritage language as best

they can, but it remains a difficult task.

REFERENCES

Barth, Fredrik 1969 ‘Introduction,’ in Fredrik Barth (ed.),

Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture

Difference, pp. 9-38. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company

Bourdieu, Pierre 1977 ‘The Economics of linguistic exchanges,’

Social Science Information, vol. 16, no. 6 , pp. 645-68

-- 1991 Language and Symbolic Power, Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press

Conklin, Nancy F. and Lourie, Margaret A..1983 A Host of Tongues,

New York: Free Press.

CORNelius, Wayne 2002 ‘Ambivalent reception: mass public

responses to the ‘new’ latino immigration to the United States,’

in Marcelo M. Suárez-Orozco and Mariela M. Páez (eds), Latinos:

Remaking America, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp.

165-189

ESSED, PHILOMENA 1991 Understanding Everyday Racism, Newbury Park,

Calif.: Sage.

FEAGIN, JOE R. 1996 ‘Old poison in new bottles: The deep roots of

modern nativism," in Juan F. Perea (ed.), Immigrants Out! The New

Nativism and the Anti-Immigrant Impulse in the United States, New

York: New York University Press, pp. 13-43

FEAGIN, JOE R. and DANIELLE DIRKS 2006 "Who is White,"

unpublished research paper, Texas A&M University.

Feagin, Joe R. and O’Brien, Eileen 2003 White Men on Race,

Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Feagin, Joe R. and SIKES, MELVIN P. 1994 Living with Racism,

Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

FEAGIN, JOE R., HERNAN VERA, and NIKITAH IMANI The Agony of

Education, Routledge, 1996.

Fischer, David Hackett 1989. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways

in America, New York: Oxford University Press

Fishman, Joshua A. 1989 Language and Ethnicity in Minority

Sociolinguistic Perspective, Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd

GLAZER, NATHAN 1975 Affirmative Discrimination, New York: Basic

Books.

Gonzalez, Gilbert G. 1990 Chicano Education in the Era of

Segregation, Philadelphia, PA: The Balch Institute Press

Gonzalez, Juan. 2000 Harvest of Empire. New York: Viking

Gramsci, Antonio 1988. The Antonio Gramsci Reader: Selected

Writings 1916-1935, David Forgacs (ed.), London: Lawrence and Wishart

Henry, Bonnie 1997 ‘What Will I Do With $21 Mil?’ Tucson

AZ:Arizona Daily Star, January 19, p.J1

Hofstadter, Richard 1955 Social Darwinism in American Thought,

Boston, MA: Beacon Press

Horton, John 1995 The Politics of Language Diversity: Immigration,

Resistance, and Change in Monterey Park, California, Philadelphia, PA:

Temple University Press

Huntington, Samuel P 2004 Who are We?: The Challenges to America’s

National Identity, New York: Simon and Schuster

Lippi-Green, Rosina 1997 English with An Accent: Language,

Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States, London: Routledge

Montoya, Margaret E. 1998. ‘Law and language(s),’ in Richard

Delgadp and Jean Stefancic (eds.), The Latino/a Condition: A Critical

Reader, pp. 574-78, New York: New York University Press

Navarrette Jr, Ruben 2005 ‘The ways we deal with language,’ The

San Diego Union-Tribune, CA, April 17, page G-3

Noriega, Jorge 1992 ‘American indian education in the United

States.,’ in M. Annette Jaimes (ed.), The state of Native America :

genocide, colonization, and resistance, Boston, MA: South End Press,

pp. 371-83

Robbins, William G. 1994 Colony and Empire: The Capitalist

Transformation of the American West. Lawrence, KS: University Press of

Kansas

SANTA ANA, OTTO 2002 Brown Tide Rising: Metaphors of Latinos in

Contemporary American Public Discourse, Austin, TX: University of

Texas Press

Shafir, Gershon 1995. Immigrants and Nationalists: Ethnic Conflict

and Accomodation in Catalonia, the Basque Country, Latvia, and

Estonia, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press

Shannon, Sheila 1999. ‘The Debate on Bilingual Education in the

U.S.’ in Jan Blommaert (ed.), Language Ideological Debates, Berlin:

Mouton de Gruyter, pp.171-199

Silverstein, Michael 1996. ‘Monoglot ‘standard’ in America:

standardization and metaphors of linguistic hegemony,’ in Donald

Brenneis and Ronald K.S. Macaulay (eds.), The Matrix of Language:

Contemporary Linguistic Anthropology Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp.

284-306

Siguan, Miquel 2002 Europe and the Languages, http://www.gksdesign.com/atotos/ebooks/siguan/europe.htm.

(Originally published in Catalan in 1995, as L' Europa de les

llengües, Barcelona, Spain: Edicions 62.)

Urciuoli, Bonnie 1996. Exposing Prejudice: Puerto Rican Experiences

of Language, Race, and Class, Boulder, CO: Westview Press

U.S. Bureau of the Census 2004 Annual Estimates of the Population

by Sex, Race and Hispanic or Latino Origin for the United States:

April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2003, Washington, D.C.:Population Division,

U.S. Census Bureau, Table 3

Wood, Nicholas 1995. ‘In the Old Dialect, a Balkan Region Regains

Its Identity,’ New York: New York Times, February 24, 2005, page A4

ENDNOTES

José A. Cobas,

Ph.D.

mailto:cobas@asu.edu

Professor, Program in Sociology

School of Social and Family Dynamics

Arizona State University

Tempe, AZ 85287-3701

(480) 965-3785

It is not enough

to prove something, one also has to seduce or elevate people to it.

Sent by Juan Ramos |

Caldera,

46, is Vice Chancellor for University Advancement of The California

State University System. The CSU system is the largest four-year

university system in the country, with headquarters in Long Beach and

23 campuses across the state. As Vice Chancellor, his portfolio

includes system-wide fundraising and development programs, legislative

affairs, community relations, alumni affairs, public affairs and

communications. He also serves as President of the CSU Foundation.

Caldera,

46, is Vice Chancellor for University Advancement of The California

State University System. The CSU system is the largest four-year

university system in the country, with headquarters in Long Beach and

23 campuses across the state. As Vice Chancellor, his portfolio

includes system-wide fundraising and development programs, legislative

affairs, community relations, alumni affairs, public affairs and

communications. He also serves as President of the CSU Foundation.

Stanley paid us a visit a in April of 2003. Alicia Armstrong (MSW)

gave Stanley a tour of The Health Care Agency here in Santa Ana, California. Stanley was just thrilled to meet all the hard working

employees that keep us healthy. Stanley

Stanley paid us a visit a in April of 2003. Alicia Armstrong (MSW)

gave Stanley a tour of The Health Care Agency here in Santa Ana, California. Stanley was just thrilled to meet all the hard working

employees that keep us healthy. Stanley  (The author is a

proud parent of a senior in high school and works as a high school

English teacher in the same school his first born will be graduating

from with honors this up and coming May of 2007. He is also the

author-editor of the textbook, Latino/a Literature in The English

Classroom)

(The author is a

proud parent of a senior in high school and works as a high school

English teacher in the same school his first born will be graduating

from with honors this up and coming May of 2007. He is also the

author-editor of the textbook, Latino/a Literature in The English

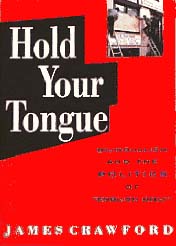

Classroom) James

Crawford, a Washington journalist, has vividly captured in his book,

Hold Your Tongue, the disturbing history and destructive politics

behind the English-only movement. He tells the stories of cities and

counties in California, Florida, Massachusetts, and other states where

activists have tried--and many have succeeded--in getting legislation

passed outlawing the use of any language but English.

James

Crawford, a Washington journalist, has vividly captured in his book,

Hold Your Tongue, the disturbing history and destructive politics

behind the English-only movement. He tells the stories of cities and

counties in California, Florida, Massachusetts, and other states where

activists have tried--and many have succeeded--in getting legislation

passed outlawing the use of any language but English.

At an age when many are lucky to walk and talk unassisted, 99-year-old

ukulele legend Bill Tapia is recording new albums, touring the nation,

and giving private lessons to a couple dozen students in his Westminster

home. "I don't want to

retire," said Tapia, a Honolulu native with a strong island

accent. "When you retire, you're gone. I'm gonna keep on

playing and working until I forget to breathe."

At an age when many are lucky to walk and talk unassisted, 99-year-old

ukulele legend Bill Tapia is recording new albums, touring the nation,

and giving private lessons to a couple dozen students in his Westminster

home. "I don't want to

retire," said Tapia, a Honolulu native with a strong island

accent. "When you retire, you're gone. I'm gonna keep on

playing and working until I forget to breathe."

On July 16, 1862, Flag Officer David Glasgow

Farragut was the first to be appointed to the rank of rear admiral.

Farragut, an Hispanic-American, became the first vice admiral in the

U.S. Navy two years later (1864), and the first full admiral in 1866. As

of April 2007, twenty one Hispanic-Americans have reached the rank of

Admiral.

On July 16, 1862, Flag Officer David Glasgow

Farragut was the first to be appointed to the rank of rear admiral.

Farragut, an Hispanic-American, became the first vice admiral in the

U.S. Navy two years later (1864), and the first full admiral in 1866. As

of April 2007, twenty one Hispanic-Americans have reached the rank of

Admiral.

*Rear Admiral Philip A. Dur (Ret.), born in Bethesda, Maryland,

earned a bachelor’s degree in Government and International Studies and

a Master’s degree in Soviet East European studies from the University

of Notre Dame. He also earned a Master’s degree in Public

Administration and a Ph.D. in Political Economy and Government from

[[Harvard University]]. Dur served as Assistant Deputy Chief of Naval

Operations; Director, Navy Strategy Division; Commander, Battle Force

United States Sixth Fleet; Commander, Cruiser Destroyer Group EIGHT;

United States Defense Attaché accredited to the Government of France;

Commanding Officer, USS Yorktown; and Director, Political Military

Affairs on staff National Security Council.

*Rear Admiral Philip A. Dur (Ret.), born in Bethesda, Maryland,

earned a bachelor’s degree in Government and International Studies and

a Master’s degree in Soviet East European studies from the University

of Notre Dame. He also earned a Master’s degree in Public

Administration and a Ph.D. in Political Economy and Government from

[[Harvard University]]. Dur served as Assistant Deputy Chief of Naval

Operations; Director, Navy Strategy Division; Commander, Battle Force

United States Sixth Fleet; Commander, Cruiser Destroyer Group EIGHT;

United States Defense Attaché accredited to the Government of France;

Commanding Officer, USS Yorktown; and Director, Political Military

Affairs on staff National Security Council. *Rear Admiral Albert Garcia, Civil Engineering Corps, from Round

Rock, Texas. His academic background include a Bachelor of Science,

Master of Science, and Ph. D. in Environmental Engineering form Texas

A&M University. Garcia has served as Commanding Officer of Officer

in Charge of Construction, Atlantic; Commodore for the 9th Naval

Construction Regiment; Assistant Chief of Staff for Reserve Affairs in

the First Naval Construction Division; he commanded Task Force Charlie

of the MEF Engineering Group and later was assigned as the Deputy

Commander of the MEF Engineering Group in Iraq. In 2004 he assumed

responsibility for consolidating several reserve augment units into a

new command, NAVFAC Contingency OICC. He assumed the duties of Deputy

Commander of the First Naval Construction Division in August 2005.

*Rear Admiral Albert Garcia, Civil Engineering Corps, from Round

Rock, Texas. His academic background include a Bachelor of Science,

Master of Science, and Ph. D. in Environmental Engineering form Texas

A&M University. Garcia has served as Commanding Officer of Officer

in Charge of Construction, Atlantic; Commodore for the 9th Naval

Construction Regiment; Assistant Chief of Staff for Reserve Affairs in

the First Naval Construction Division; he commanded Task Force Charlie

of the MEF Engineering Group and later was assigned as the Deputy

Commander of the MEF Engineering Group in Iraq. In 2004 he assumed

responsibility for consolidating several reserve augment units into a

new command, NAVFAC Contingency OICC. He assumed the duties of Deputy

Commander of the First Naval Construction Division in August 2005.

Upon

reaching womanhood, she met and fell in love with Marcelino Ramirez

Bautista. Marcelino, a young and handsome man was the son of Tiburcio

Muro Bautista and Petra Arteaga Ramirez.

Upon

reaching womanhood, she met and fell in love with Marcelino Ramirez

Bautista. Marcelino, a young and handsome man was the son of Tiburcio

Muro Bautista and Petra Arteaga Ramirez.

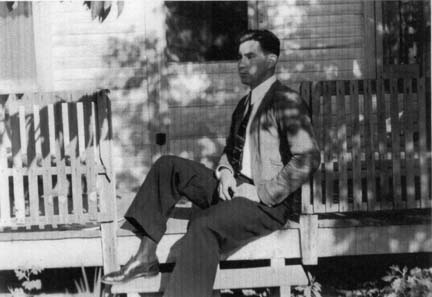

Marcelino

(center) visiting Marquez Bautista (cousin) in Upland, California in the

1940’s

Marcelino

(center) visiting Marquez Bautista (cousin) in Upland, California in the

1940’s

During

this time Marcelino traveled to Chicago, Illinois and California looking

for work, but jobs were scarce. For a while he returned to Zacatecas

only to leave his family again. Finally, while staying with his sister

Maria in California he secured a job as a construction worker.

During

this time Marcelino traveled to Chicago, Illinois and California looking

for work, but jobs were scarce. For a while he returned to Zacatecas

only to leave his family again. Finally, while staying with his sister

Maria in California he secured a job as a construction worker.

would

return to Juarez and further assist his ill sister and now, mother.

Dismayed Henry found them both not only seriously ill, but abandoned by

his sick sister’s husband. To further compound the situation,

Guadalupe now had a one year old daughter. In time Anastacia’s health

improved. However, when they attempted to re-enter the United States,

Guadalupe was denied entrance because she was still too ill. The

situation resulted in Anastacia and Henry taking Guadalupe back to

Zacatecas and placing her in a hospital for long term treatment. Sadly,

in 1957, she passed away just months after being hospitalized.

After her passing, Henry again, returned to Juarez and brought Guadalupe’s

daughter to United States to live with her maternal grandparents.

would

return to Juarez and further assist his ill sister and now, mother.

Dismayed Henry found them both not only seriously ill, but abandoned by

his sick sister’s husband. To further compound the situation,

Guadalupe now had a one year old daughter. In time Anastacia’s health

improved. However, when they attempted to re-enter the United States,

Guadalupe was denied entrance because she was still too ill. The

situation resulted in Anastacia and Henry taking Guadalupe back to

Zacatecas and placing her in a hospital for long term treatment. Sadly,

in 1957, she passed away just months after being hospitalized.

After her passing, Henry again, returned to Juarez and brought Guadalupe’s

daughter to United States to live with her maternal grandparents.

Anastacia’s

final years were spend growing closer to her eldest son, Henry. Their

memorable years from the old country produced a unique bond. Whatever

mother needed Henry was there for

her, and living on the same block as our parents obviously helped. And

both she and Marcelino always looked forward to visiting their youngest

son (Jess), daughter-in-law, and grandchildren in Denver, Colorado.

Anastacia’s

final years were spend growing closer to her eldest son, Henry. Their

memorable years from the old country produced a unique bond. Whatever

mother needed Henry was there for

her, and living on the same block as our parents obviously helped. And

both she and Marcelino always looked forward to visiting their youngest

son (Jess), daughter-in-law, and grandchildren in Denver, Colorado.

My life differs somewhat from end

Santos from Laredo, Texas who grew up in an Hispanic community in south

Texas; but, discrimination was present from the time of my parents who

lived in Kingsville, Texas in the '30s.

My life differs somewhat from end

Santos from Laredo, Texas who grew up in an Hispanic community in south

Texas; but, discrimination was present from the time of my parents who

lived in Kingsville, Texas in the '30s.

In celebration of the 225th founding of Mission San

Buenaventura in Ventura, March 31, 1782, Los Soldados from El Presidio

State Historic Park participated in ceremonies at the mission on

Saturday, March 31, 2007. Father Damian Fernando of the parish at the

mission hosted the event, which included local Native American children

under the guidance of Mary Mendoza whose own grandchildren participated

in the event. Soldiers in the procession were directed by Jim Elwell

Martinez who portrayed Lt. Ortega. Jim Martinez as a native of

In celebration of the 225th founding of Mission San

Buenaventura in Ventura, March 31, 1782, Los Soldados from El Presidio

State Historic Park participated in ceremonies at the mission on

Saturday, March 31, 2007. Father Damian Fernando of the parish at the

mission hosted the event, which included local Native American children

under the guidance of Mary Mendoza whose own grandchildren participated

in the event. Soldiers in the procession were directed by Jim Elwell

Martinez who portrayed Lt. Ortega. Jim Martinez as a native of  Ventura

and welcomed the opportunity to be a part of the founding ceremony.

Ventura

and welcomed the opportunity to be a part of the founding ceremony.  On Easter Sunday morning, March 31, Serra blessed the site under the

shadow of the hills far from the river and close to the sea. The Cross

was raised and blessed. Within an enramada, Serra sang a High Mass and

preached. After that, the soldiers took possession of the land in the

name of the king, permission having been obtained from the natives

through interpreters to settle here. Following this the Te Deum of

thanks was sung as Serra founded his 9th and last Mission in

Upper California.

On Easter Sunday morning, March 31, Serra blessed the site under the

shadow of the hills far from the river and close to the sea. The Cross

was raised and blessed. Within an enramada, Serra sang a High Mass and

preached. After that, the soldiers took possession of the land in the

name of the king, permission having been obtained from the natives

through interpreters to settle here. Following this the Te Deum of

thanks was sung as Serra founded his 9th and last Mission in

Upper California. The founding ceremony in Ventura was organized by the 225th

Anniversary Committee. Participants included Deacons in Training and

Visiting Priests and the Chumash descendants of Saticoy Native Americans

(Turtle Clan). Chumash re-enactors opened the ceremony with a song of

welcome in the native tongue. During the ceremony, they provided sage

incense within the church and sang sunrise/eagle songs.

The founding ceremony in Ventura was organized by the 225th

Anniversary Committee. Participants included Deacons in Training and

Visiting Priests and the Chumash descendants of Saticoy Native Americans

(Turtle Clan). Chumash re-enactors opened the ceremony with a song of

welcome in the native tongue. During the ceremony, they provided sage

incense within the church and sang sunrise/eagle songs.  Chumas

songs

Chumas

songs In one of the photos Jim Martinez is standing in front of an original

ruin settling tank for the Mission water system. Mike Hardwick (Neve) is

standing in the garden in front of the fountain with the side of the

mission behind him. The lady with the green dress is wearing an outfit

that I believe she made. I don’t know here name, but it is her little

daughter that is wearing the soldier’s uniform.

In one of the photos Jim Martinez is standing in front of an original

ruin settling tank for the Mission water system. Mike Hardwick (Neve) is

standing in the garden in front of the fountain with the side of the

mission behind him. The lady with the green dress is wearing an outfit

that I believe she made. I don’t know here name, but it is her little

daughter that is wearing the soldier’s uniform.

In April of 1990, this living history group formed to recreate the

Soldado de Cuera of the period 1769-1821. The group is chartered to

authentically portray the Spanish presidial soldier by means of

reenactments of military drill, use of period costumes, role playing,

and research into period history. Los Soldados re-enact the soldiers,

civilians and their families as they lived at the Presidio of Santa

Barbara in the period of time following the founding of the presidio in

1782.

In April of 1990, this living history group formed to recreate the

Soldado de Cuera of the period 1769-1821. The group is chartered to

authentically portray the Spanish presidial soldier by means of

reenactments of military drill, use of period costumes, role playing,

and research into period history. Los Soldados re-enact the soldiers,

civilians and their families as they lived at the Presidio of Santa

Barbara in the period of time following the founding of the presidio in

1782. Valenzuela, Jack Romero and Bud Decker participated in the annual Yuma

Crossing Day in historic Yuma, Arizona. Los Soldados were part of

the scores of re-enactors who helped celebrate the history of the Yuma

Crossing and the story of the diverse community that developed in what

is now known as the

Valenzuela, Jack Romero and Bud Decker participated in the annual Yuma

Crossing Day in historic Yuma, Arizona. Los Soldados were part of

the scores of re-enactors who helped celebrate the history of the Yuma

Crossing and the story of the diverse community that developed in what

is now known as the

We're

also celebrating 23 years of politically relevant, historical and

hysterical theater work as well as the launch of public ticket sales

to our L.A. premiere of Culture Clash's

We're

also celebrating 23 years of politically relevant, historical and

hysterical theater work as well as the launch of public ticket sales

to our L.A. premiere of Culture Clash's  Renowned Artist Nacho Duato first emerged as a choreographer to watch while a dancer with the Nederlands Dans Theater and quickly became the company's resident choreographer. Now one of the world's most sought-after artists, his works are in the repertoires of many great companies including American Ballet Theatre, Australian Ballet, the Royal Ballet and San Francisco Ballet, just to name a few.

Renowned Artist Nacho Duato first emerged as a choreographer to watch while a dancer with the Nederlands Dans Theater and quickly became the company's resident choreographer. Now one of the world's most sought-after artists, his works are in the repertoires of many great companies including American Ballet Theatre, Australian Ballet, the Royal Ballet and San Francisco Ballet, just to name a few.

Dedicated to the memory of William Arvizu. He instilled in me a deep sense of the family pride and awareness of what our Arvizu ancestors contributed to the making of what is now California of today.

Our Arizu history parallels the history of many other Latino families who helped to settle the Western United States over many past generations.

Dedicated to the memory of William Arvizu. He instilled in me a deep sense of the family pride and awareness of what our Arvizu ancestors contributed to the making of what is now California of today.

Our Arizu history parallels the history of many other Latino families who helped to settle the Western United States over many past generations.

On May 19, 2007,"La Gente del Presidio", a volunteer group,

will hold a historic re-enactment and living history at the Grand

Opening of the newly constructed adobe Presidio Tower and Wall which

depicts one corner of the original one. I just made a copy

On May 19, 2007,"La Gente del Presidio", a volunteer group,

will hold a historic re-enactment and living history at the Grand

Opening of the newly constructed adobe Presidio Tower and Wall which

depicts one corner of the original one. I just made a copy  These photos are from our third annual Living History Fair circa

1775-1856, held March 24, 2007. There were soldados making leather

goods and other items, mujeres carding and spinning wool & cotton,

children's games, soap making, carpentry, indigenous grains, meats and

vegetables plus those introduced by the Spaniards, posole to taste and

tortilla making. This is a part of the Tucson Presidio Trust for

Historic Preservation.

These photos are from our third annual Living History Fair circa

1775-1856, held March 24, 2007. There were soldados making leather

goods and other items, mujeres carding and spinning wool & cotton,

children's games, soap making, carpentry, indigenous grains, meats and

vegetables plus those introduced by the Spaniards, posole to taste and

tortilla making. This is a part of the Tucson Presidio Trust for

Historic Preservation.

Formerly a hay