|

Somos Primos Dedicated

to Hispanic Heritage and Diversity Issues |

|

|

|

|

|

Somos Primos Dedicated

to Hispanic Heritage and Diversity Issues |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Content

Areas Feature: From the Barrio to Washington United States National Issues Action Item Education Bilingual Education Culture Business Anti-Spanish Legends Military & Law Enforcement Heroes Patriots of American Revolution Cuentos Literature |

Surname Orange County,CA Los Angeles,CA California Northwestern US Southwestern US African-American Indigenous Sephardic Texas East of Mississippi East Coast Mexico Caribbean/Cuba |

Spain

International History Family History Archaeology Miscellaneous Networking SHHAR Meetings Jan 26: Mar 22: Conference April 26 May 24: Aug 23: End |

|

Letters to the Editor : |

| Estimada Mimi Lozano:

Le envio un caluroso saludo y gran felicitación por su magnífica y expléndida página de Somos primos, que veo con asiduidad e interés cada mes, es una valiosa cotribución a mantener unidos nuestros lazos familiares y a reecontrarnos con nuestros primos y gran familia. Le envío por si le resulta de interés un pequeño trabajo que he titulado "los Fundadores y Pobladores de la Ciudad de Salvatierra, Guanajuato. 1644", aunque el título que va en el correo adjunto sea algo diferente, lo pongo a su consideración y ojalá sea de alguna utilidad. Le enviaré antes de navidad una tarjeta virtual extensiva para usted y la gran familia mexicana de Estados Unidos. Reciba un fuerte abrazo. Si lo desea, puedo adjuntar luego algunos

gráficos. Dear Mimi... Once again, I MUST extend my total and sincere congratulation's to you for a marvelous issue of SOMOS PRIMOS. How on earth do you find the time.

|

| The names listed as

contributors in each issue have contributed to that issue specifically. Big Thank you for sharing with your Primos!! |

| ------------------------------- Somos Primos Staff: Mimi Lozano, Editor Mercy Bautista Olvera Bill Carmena Lila Guzman Granville Hough John Inclan Galal Kernahan J.V. Martinez Armando Montes Dorinda Moreno Michael Perez Rafael Ojeda Ángel Custodio Rebollo Tony Santiago John P. Schmal Howard Shorr Ted Vincent Contributors: Rudy Acuña Judge Fredrick Aguirre Linda Aguirre Jake Alarid Ruben Alvarez Dan Arellano Dr. Armando A. Ayala Elaine Ayala Mercy Bautista-Olvera Joseph Bentley Juan Blackaller Granada Belia Buenavbentura Reveles Roberto Calderon, Ph.D. Bill Carmena Henry J. Casso, Ph.D. Gus Chavez Yolanda Chavez Magdaleno |

---------------------------------- Manuel Caro PhD Jim Carr Dr. Henry P. Casso Rafael Castellanos Cristina Castillo Grace Charles Elena Cortaza Jack Cowan Boyd Delarios Sal Delvalle Leticia Duran Charlie Erickson Armando M Escobar O Lupe Fisher Lynne Furet Doherty Willie Galvan Daisy Wanda Garcia Granville Hough, Ph.D. John Inclan Galal Kernahan Carlos López Dzur Pat Lozano Larry Luera Gilbert "Magu" Lujan Enrique Maldonado Quintanilla Manny Marroquin Lucas Martínez Prof. Juan Marinez Dorinda Moreno Carlos Muñoz, Jr. Ph.D. Mª Ángeles O'Donnell Olson Rafael Ojeda Gloria Oliver Jose Luis Orozco Patrick Osio Jose M. Pena Roberto Perez Guadarrama |

--------------------------------- Lauro E. Garza Henry Godines Lila Guzman, Ph.D. Laura E. Gómez, Ph.D. Rafael Jesús González Eddie Grijalva Prof. Manuel Hernandez Willie Perez Jess Quintero Ángel Custodio Rebollo Armando Rendon, Ph.D. Rogelio Reyes, Ph.D Alfonso Rodriguez Dr. Armando Rodriguez Héctor Javier Rodríguez García Christy Rodriguez Rosa Rosales Lupe Saldana Verle E. Salinas-Wenneker US Congresswoman Loretta Sanchez Tony Santiago John P. Schmal Howard Shorr Frank M. Sifuentes Greg P. Smestad, Ph.D. CA Assemblyman Jose Solorio Alva Moore Stevensson Ernest Uribe Ricardo Valverde Janete Vargas Dr. Santos C. Vega Cris Villasenor Pepe Villarino Ted Vincent Martin Wisckol afriampub@aol.com rgrbob@earthlink.net saballod@bellsouth.net |

| SHHAR

2008

Board: Bea

Armenta Dever, Gloria Cortinas Oliver, Mimi

Lozano Holtzman, Pat Lozano, Yolanda Magdaleno, Henry Marquez, Michael Perez, Crispin Rendon, Viola Rodriguez Sadler,

John P. Schmal. |

||

|

|

|

|

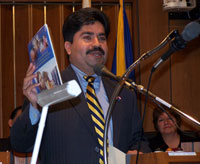

Rodriguez rose through the United States educational system to become the first Hispanic principal of a junior and senior high school in San Diego. He became only the second Latino to be a college president in California and served in the administrations of four U.S. presidents. His list of honors and accomplishments is long and impressive: Rodriguez received two honorary doctorates of letters, served as the nation’s first director of the Office for Spanish Speaking American Affairs and as U.S. Assistant Commissioner of Education. Inspired by the courage of giants like New Mexico Senator Dennis Chavez, his commitment to social reform and equality motivated him to become a leader in politics and civil rights. He was a leader in the 1966 Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Walkout in Albuquerque, a pivotal moment that sparked change in federal policy. Twelve years later Rodriguez was appointed as EEOC Commissioner. Rodriguez was influential in shaping education on local and national levels. A Latino pioneer in the world of electoral politics, a mentor to leaders of burgeoning Latino advocacy groups, an international reformer, and a labor rights activist, Armando Rodriguez is the hero in the story of a boy from the barrio who became an instrument of change for his community and country. His life’s lessons are not those of a bygone era but are important to today’s youth.

|

|

Armando Rodriguez will speak at the following venues and all events are free and open to the public.

Armando Rodriguez lives in El Cajon, California, with his wife of fifty-nine years, Beatriz. The book was edited by Bettie Baca, a former government executive, and is a community activist and editor in the public and private sectors and Keith Taylor, a retired U.S. Navy officer and a long time columnist for The Navy Times. Lionel Van Deerlin, who wrote the foreword, is a former U.S. Congressman from San Diego, California, and is professor emeritus of journalism at San Diego State University and a columnist for The San Diego Union-Tribune. From the Barrio to Washington: An Educator’s Journey is available at bookstores or directly from the University of New Mexico Press. To order, please call 800-249-7737 or visit www.unmpress.com. ISBN: 978-0-8263-4381-9- MEDIA NOTE: For more information or to schedule an interview with Armando Rodriguez, please contact Amanda Sutton, UNM Press publicity, at 505-272-7190 or asutton@unm.edu

|

| Close

Encounters with Dr. Hector P. Garcia The Journey to Latino Political Representation Legacy: Spain and the United States in the Age of Independence Smithsonian Latino Center just got a big-time sugar daddy Slim and the Smithsonian Latino Center Pew Hispanic Center: Research and Surveys on the U.S. Hispanic Population |

|

Part I

|

|

|

|

|

|

During the early days, Forumeers would travel to

far away places to meet with potential members. Through the decades,

these members remained loyal and worked hard for the organization

following Dr. Hector’s example. Dr. Hector kept their loyalty because

he gave them an investment and a role in his organization, the American

G.I. Forum (AGIF). The

WILLIE GALVAN The AGIF was growing tremendously during the late 50's with chapters being organized throughout Texas and the United States. Dr. Garcia came to Victoria, Texas, a small town between Corpus Christi and Houston on the Gulf Coast, for the first organizing meeting of the AGIF Victoria Chapter in 1958. There were about 13 Veterans assembled at a local Mexican restaurant anxiously awaiting Dr. Garcia's arrival to clue us in about the American GI Forum. He arrived soon enough, and with his driver carrying his briefcase, introduced himself and talked nonstop for about 20 minutes about the GI Forum. When he finished talking, he said, "Okay, let's appoint officers," and pointed to me and said, "Willie, you're the Chairman..." and continued pointing to others, appointing all the officers. Then Dr. Hector said, "You are a duly organized chapter" and then asked us what our plans were and what we were going to do. We were stunned, of course and had no answers. "Well, I've been told that you have a lot of problems here in Victoria, like all the other Texas cities with a majority of Latinos. Okay", Dr. Hector said, "do you have Latinos on your City Council?" Of course, we did not, so he said, "Willie, you're running for City Council in the next election", and he pointed to another person and said, "You're running for the school board", another for County Commissioner and another for the College Board of Trustees. We were completely overwhelmed and thought he was out of it. Well, three of us ran for public offices, all of us lost. I lost by 87 votes running for City Council. We were surprised that after a few years some Hispanics were elected to various offices, this due to Dr. Garcia's message to get involved to change conditions and do something in our community. He stayed for about 30 minutes at the organizing meeting because he had to go to another organizing. He said, "Willie, ask me some questions about the Forum." I answered "Doctor, I don't know what to ask." He seemed annoyed, and said, "You will next time. And by the way, you are meeting every two weeks until you get this chapter up and going, and report to me." He waved goodbye and left. We sat there, completely baffled, myself, mostly, as I did not know the first thing about running a meeting. I finally learned and have been at it since 1958; and am proud to say that the Forum has been my extended family since then. Willie Galvan, State Commander

WILLIE PEREZ, EL COYOTE I may or may not have shared this episode or incident of Dr. Hector and me. As you know, I was once in charge of programs and assemblies at Miller High School. On one occasion Dr. Hector agreed to come to Miller High School and speak to our high school student body (mostly 10, 11, and 12th graders) about the GI Forum, the Mexican-American Civil Rights Movement, and Mexican=American military heroes. Needless to say, the auditorium was full---standing room only. The auditorium held between 600-700 warm bodies. Not only was the audience receptive but also they gave Dr. Hector a standing ovation at several intervals. After the program, I asked Dr. Hector what he thought about the students and the school. Of course, he said he was glad to have been asked to speak. However, he said that he was sadden by the fact that his work and name were a household word at Yale, Harvard, etc. but in Corpus Christi students knew very little about him or his work. Anyway, after that thought and comment, I invited him to have lunch with me at the school cafeteria. Very tactfully, Dr. Hector said he had had his share of school cafeteria lunches and invited me to lunch. So, I was privileged and honored to have been invited to lunch by Dr. Hector to the Chicken Shack on Leopard Street. I will never forget this treat. This took place sometime in 1989. But the day after Dr. Hector and I had lunch. He went to his car and took out two copies of the book "among the valiant" by a Mr. Morin and donated them to Miller High school. Recently, I went back to miller and the books were still in the library. I am glad that Dr. Hector shared these books with our students and that they are still being read and enjoyed by our students Incidentally, we, the Longoria Chapter, are presently working with the school administration so that CCISD incorporates Dr. Hector's legacy into the curriculum. Guillermo Perez, Commander of the Pvt. Felix Longoria Chapter, Corpus Christi, TX and State Secretary for the Texas American G.I. Forum

I first met Dr Hector P. Garcia in the late 1970's at a AGIF conference in Los Angeles. I was instantly impressed by his charisma, passion and his ability to motivate the audience. I did not really get to know him until I became Vice Commander of the AGIF in 1982; the late Jose Cano was the National Commander at that time. Mr. Cano, being from Texas, was real close to Dr. Garcia and on many occasions he invited me to meetings where Dr. Garcia would be present and, therefore, I became acquainted with Dr. Garcia. One of the first things Dr. Garcia asked me when I first met him, "Alarid, do you know where the name Alarid came from?" He proceeded to give me a history lesson on the origin of my name. The version was correct; apparently he had read the book "Origins of New Mexico Families" by Fray Angelico Chavez. I became National Commander in 1983 and during the one year that I held that position I had the occasion to travel with Dr. Garcia and attend meetings with him. No matter who his audience was, he was prepared and knew how and when to deliver his message and motivate his audience. His agenda was veterans, education, civil rights and the youth. He had to have a little humor in his message and he was good at telling a joke. Dr. Hector would have people laughing before he delivered the punch line. He also wouldn’t miss the opportunity to tell a good Texas Aggie joke.

Jake Alarid [[Editor: If you recognize any of

the individuals in the photos, please let Wanda Garcia know. Thank you to Lupe Saldana for responding, he wrote:

|

|

| Book: The Journey to Latino Political

Representation By John P. Schmal |

|

|

|

|

| The Latino Vote: An Introduction

The first chapter summarizes the problems that Latino voters in the U.S. faced in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It highlights the beginning of a new era and a new generation that emerged from World War II to galvanize Latino voters and fight for their rights as citizens. The chapter also gives a summary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and how it enhanced the voting rights of Latinos. California (1848-1899) This section of the book outlines the political transition from Mexican California to a California managed by the U.S. It describes the significant representation of Hispanics during the first few decades, but also follows the gradual erosion of Latino voting rights that started in the 1870s and reached its nadir with the passing of the English Literacy Requirement in 1894. California (1900-1964) The third chapter details the slow process in which Latinos began to make their way back into the political system of California. With the end of World War II, Edward Roybal became a catalyst for change as he made his name on the Los Angeles City Council. However, overall Latino representation in California in 1964 was still just a dream. California (1965-1975) This chapter follows the Chicano movement as Latinos make strides towards representation in various parts of California. Although the progress is slow, it continues, and the establishment of the Chicago Legislative Caucus marks a turning point. Texas (1836-1964) This chapter details the early Latino representation in Texas as the rights of Mexican-Americans begin to erode, culminating in the Poll Tax of 1902. As in California, a new generation of Latinos comes forward after World War II to begin the process of regaining representation in their communities. Texas (1965-1980) This chapter details the election of key Latinos to office in the Texas State Legislature across the three decades that followed the enactment of the Twenty-Four Amendment and the Voting Rights Act. This chapter details the somewhat sporadic representation of Latinos in the U.S. Congress across a 137-year period. The elections of representatives from Florida, New Mexico, California, Puerto Rico and Louisiana are described. The U.S. Congress (1960-2005) This chapter summarizes the obvious lack of Hispanic representation in Congress up to 1960 and explains the revival of the Latino voting voice with the election of key individuals to the U.S. Congress starting in the 1960s and accelerating in the subsequent decades. Texas: Moving into a New Century This chapter follows the path of Texas elections as Tejano representation in various parts of the state increases dramatically. Los Angeles City Government This chapter explores Los Angeles city politics as it evolved from 1848 into the twentieth century. For more than six decades, Latino representation in the City Council essentially disappeared. With the arrival of Edward Roybal in 1949, representation was restored. But when Roybal resigned from the Council to run for Congress in 1962, Hispanic representation essentially disappeared again until 1985. There is considerable discussion about the lawsuits that brought Gloria Molina and other personalities to the City Council. California (1978-2005) The final chapter in this book summarizes the steady increase in Chicano representation in the California legislature. There is discussion of the landmark 1982 election that brought Gloria Molina, Richard Alarcon and others into key state positions. This chapter also illustrates how the passing of Proposition 187 in 1994 served as a catalyst to promote Latino political involvement, leading to significantly increased representation by the beginning of the New Millennium. Available through: http://heritagebooks.com/ |

|

| Legacy: Spain and the United States in the Age of Independence |

|

George Washington at the Battle of Princeton by Charles Willson Peale (1741 – 1827) Oil on canvas, 1779. Private Collection. WASHINGTON, DC.-The National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian Latino Center, together with the Sociedad Estatal para la Acción Cultural Exterior and the Fundación Consejo España-Estados Unidos, present the exhibition “Legacy: Spain and the United States in the Age of Independence, 1763-1848,” which examines the story of Spain’s role in the history of the United States. Although it is widely known that France was a key partner in the fight for American independence from Britain, few are aware that independence was only possible with the financial and military support of Spain. “At the heart of the National Portrait Gallery is our goal to ensure that the country remembers its past,” said Marc Pachter, director of the Portrait Gallery. “The aptly named exhibition ‘Legacy’ explores the role of Spain and Mexico in the development of this nation with that goal in mind.” The exhibition brings together stunning portraits and compelling original documents to explore Spain’s role in the American Revolutionary War and the development of the United States. It begins in 1763—when the Treaty of Paris was signed and Spain controlled approximately one-half of the land that is now part of the United States—and continues through 1848, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed to end the Mexican-American War. The exhibition also will illustrate the social, cultural and political influence of Hispanic culture through 1848. “This exhibition invites people to immerse themselves in this era and learn more about Spain’s key role in the Revolution and the early days of the American republic through extraordinary portraits, original treaties and maps,” said Carolyn Kinder Carr, deputy director of the National Portrait Gallery and “Legacy” exhibition co-curator. “The political and geographic changes that happened during this 85-year period still reverberate in American culture today.” Some of the individuals represented by renowned artists include names familiar to the American story: “George Washington” by Charles Willson Peale, “Benjamin Franklin” by Joseph Siffred Duplessis and “Davy Crockett” by Chester Harding. But the exhibition also demonstrates the connections between these Americans and political figures in Spain during the American Revolution and later the individuals, both Americans and individuals of Hispanic descent, who led Florida, Louisiana, the Upper Mississippi, California and the southwest. For example, three men who determined Spain’s foreign policy during the time of the American Revolution were King Carlos III, who is portrayed by court painter Anton Raphael Mengs; José Moñino, the Count of Floridablanca, who was prime minister and is portrayed by Folch de Cardona; and Pedro Pablo Abarca de Bolea, the Count of Aranda, who was a longtime champion of the American cause and was painted by Ramón Bayeu, brother-in-law to the famed Francisco de Goya. The exhibition includes five portraits by Goya: those of the Conde de Cabarrús, King Carlos IV of Spain, Felix Colón de Larriategui, King Ferdinand VII of Spain and el general don José de Urrutia. “Few Americans realize that Hispanics have played an important role in our country since its founding,” said Pilar O’Leary, director of the Smithsonian Latino Center. “The fact that Hispanic-Americans fought alongside Anglo-Americans to help obtain independence from Britain, for example, is not often taught in U.S. classrooms or history books today. This exhibition will raise public awareness of the historical role and roots of Hispanic-Americans in U.S. society.” Sent by Lila Guzman, Ph.D. lorenzo1776@yahoo.com |

| Slim and the Smithsonian Latino Center |

|

December 05, 2007 Slim and the Smithsonian Latino Center http://latino.si.edu/ Smithsonian Latino Center just got a big-time sugar daddy. The center announced yesterday that it signed a memorandum of understanding with Fundación Carso. It's an important connection. The Mexican foundation is the philanthropic arm of Grupo Carso, which runs the Museo Soumaya in Mexico City. More importantly, Grupo Carso is owned by Carlos Slim, a Mexican businessman who's reportedly one of the richest men in the world. The partnership will lead to "a series of exhibitions, public programs, educational materials" and other events at the Smithsonian. This is exciting for several reasons. Some of the programming will be scheduled around a historic moment in the Americas — the 200th anniversary of Mexico's independence in 2010 and that of other Latin America countries. A virtual museum could be in the works to bring the Smithsonian's Latino and Latin American collections to the world, and the Latino Center has agreed to emphasize distance learning, which may bring live concerts, lectures and other programs to virtual viewers via pod casts or satellite in museums throughout the country. But this announcement also may help the Smithsonian Latino Center reach an even bigger goal national Latino museum on the Washington Mall. There's still a spot open on that prestigious row, one that Hispanic Americans so deserve. Pilar O'Leary, the center's director, said it right about what Grupo Carso's support can lead to in even more important ways. "The Smithsonian Latino Center and Museo Soumaya share the belief that art — in all its mediums — is an important tool in fostering understanding between cultures." Amen. Elaine Ayala http://blogs.mysanantonio.com/weblogs/latinlife/2007/12/slim_and_the_smithsonian _latin_1.html http://blogs.mysanantonio.com/weblogs/latinlife/ http://blogs.mysanantonio.com/weblogs/latinlife/2007/12/

|

| Pew Hispanic Center: Research and Surveys on the U.S. Hispanic Population | |

http://pewhispanic.org/ |

|

|

Adopted Valor:

Immigrant Heroes |

|

FOREIGN BORN MEDAL OF HONOR RECIPIENTS PRIVATE FIRST CLASS SILVESTRE HERRERA - WWII Upon receiving his draft papers, Silvestre Herrera, a 27-year-old father of three, learned for the first time that he was not an American citizen, rather, that he was born in Mexico, adopted by his uncle after his parents died. Because he wasn’t an American citizen, Silvestre wasn’t obligated to serve in World War II. Silvestre’s reply was defiant, he said, "I'm going anyway." He didn't want anybody else to die in his place. He said, "I am a Mexican-American and we have a tradition, we're supposed to be men, not sissies." As a member of the Texas National Guard, 36th Infantry Division, Silvestre found himself fighting in France on March 15, 1945. Advancing with his platoon along a wooded road, they were stopped and pinned by heavy enemy machinegun fire. As the rest of the unit took cover, he made a 1-man frontal assault on the German strongpoint, shooting three and capturing eight enemy soldiers. But Silvestre's day was just beginning. When the platoon resumed its advance, Silvestre’s unit was subjected to fire from a second emplacement, beyond an extensive minefield. Herrera ran forward, intending to take cover behind a boulder, when he stepped on anti-personnel landmine that blew him into the air. When he came down, he hit another mine. He lost both legs just below the knee. Despite his violent injury, Herrera somehow managed to hold onto his M-1 rifle. After applying a bandage to his legs he braced himself against the boulders for cover and began firing at the enemy. He hit at least one of the Germans and forced the others to stop shooting and take cover. Later Silvestre said, "I was protecting my squad. I was trying to draw their fire. I was fighting them on my knees." Despite intense pain, two severed legs and an unchecked loss of blood, he pinned down the enemy with accurate rifle fire allowing another squad the enemy gun by skirting the minefield and rushing in from the flank. Silvestre returned stateside to recover from his wounds and five months later he was decorated with the Medal of Honor personally by President Truman. His service both during World War II as a soldier, and as a patriot since that fateful day in France, brought him continued honors and distinction. An elementary school in Phoenix bears his name, and he is the recipient of several community awards. Herrera died at his home in Glendale, Arizona, on November 26, 2007. 715 OF THE 3,410 CONGRESSIONAL MEDAL OF HONOR RECIPIENTS IN AMERICA'S HISTORY - MORE THAN 20 PERCENT - HAVE BEEN IMMIGRANTS TO THIS NATION.

Silvestre Herrera Sent by Ricardo Valverde |

|

Herrera men who served in the U.S. Military |

|

Source: Undaunted

Courage: Mexican American Patriots of World War II |

| Bartolomeo de Herrera was a 20 year old

soldier in New Mexico, making muster roll in 1598 under the

leadership of Juan Onate. In Pensacola, Florida in 1781, during the American Revolution, Spain's forces in support of the American colonists included a Juan Herrera, commanding the galley San Peregrino. |

Dr.

Granville Hough's (retired West Point) identified 25 Herrera serving

during the American Revolution

in the present day Southwest. During the Civil War Hispanics served on both the Union and Confederate side. Two Herrera's were identified. During WW I, 1,548 draft cards were filled out by Herrera men. |

| During World War II, 5 Herrera brothers from

Placentia, California served, Augustine, Ignacio, Peter, Manuel, and

Emilio. During the Korean War, Sgt. Robert Herrera received the Bronze Star, in addition to a Purple heart, and Korean SVC Medal. Vietnam Wall includes the following Herrera's

|

The numbers of Hispanic-Americans who have served in

the nation's major wars are:

American Revolution (1775-1783): 4,000 Civil War (1861-1865): 10,000 World War I (1914-1918): 18,000 World War II (1939-1945): 500,000 Korean War (1950-1953): 43,400 Vietnam War (1963-1973): 80,000 Persian Gulf War (1990-1991): 25,000 SOURCE: U.S. Department of Defense

|

|

|

|

|

I am a former Marine Corps Infantry Rifleman who served in Vietnam until I was wounded in April of 1967. In October of 1988 Newsweek published my article " A Chicano in Vietnam" that later served as the impetus for my dissertation- FROM HOMER TO HOMEBOY: Heroism, War and Memory in Chicano Life and Letters (1999) In that work I explored the theme of war in Chicano literature and examined within that theme how the idea of heroism- as service to country, to home and homeland, to family and oneself, was expressed. In this frame, I also compared the idea and definitions of masculinity and manhood in Latino culture against the stereotypical, distorted and emasculating images and myths of Latino men in American literature. I chronicled the experiences of Chicano/Mexican American War Veterans who served in the U.S. Military - from the Civil War through Vietnam. I examined the narratives of these veterans, and the racial, economic, social-political realities that reflected their participation in this country's wars. Sincerely, Manuel Caro PhD mcaro3@gmail.com Editor: Dr. Caro said that the University of Michigan maintains an index to Ph.D. http://www.lib.umich.edu/find/databases.html Another resource is the East Los

Angeles Library. The library is host to the Chicano

Resource Center, established in 1976, ...They maintain a

collection of dissertations written by/about

Hispanics/Latinos/Chicanos, etc. |

|

| A Website called: Ken Burns Hates Mexicans | |

|

Six months after starting this blog, and two days before Ken Burns broadcasts his epic WWII doc this Sunday, it's as good a time as any as to explain why I titled this ongoing project Ken Burns Hates Mexicans. A recent TV column critiquing Burns and his upcoming series, The War, began with a reference to this blog suggesting I'm implying the PBS filmmaker actually hates Mexicans. My bad for not explaining my intentions more precisely -- and for not including a definition of the concepts of metaphor and satire somewhere amongst my Led Zeppelin posts. For the record: of course I don't believe Ken Burns actually hates Mexicans. Vato may have an issue with over-fried chimichongas (as I do) or derivative roc en espanol (as should everyone), but who knows?, I never met the guy. When I say "Ken Burns" I don't literally mean the so-called liberal white guy with the dorky bowl haircut who makes tedious so-called "American" documentaries for PBS. Instead when I say "Ken Burns" I'm talking about the total, whole, and collective so-called liberal white media bloviating across the multicultural landscape. About Latinos, about race and class, about "the other." This includes not only those with dorky bowl haircuts, but those making movies called...oh, I don't know, Quinceanera. And when I say these types "hate," I don't literally mean dislike intensely, or having aversion towards, but instead I'm talking about the ignorance, simplistic reductions, misunderstandings, and/or condescension that generally define these gringos' opinions, statements, and, yes, even their documentaries about Mexicans. That is, of course, those few times these well-intentioned do-gooders actually turn their fickle gaze on Brown people. Indifference being another variation of the "hate" metaphor. And when I say "Mexicans" I mean Raza in general. Brown people. Mi gente. U.S. Latinos primarily, but not always. Finally, this is not to say that I don't disagree with much of the Latino criticism of the Burns series, because I don't. For me, a Burns film is like an Ansel Adams photo, middlebrow, pretty to look at, but devoid of real thought or analysis. But the issues raised by his latest series go much deeper than that. Stepping back for a moment from the metaphoric and into the specific, for me Burns' The War embodies all of the issues mentioned above -- and more. Throughout his long career Burns has constantly talked about his films as being stories about "America." Sure they may ostensibly be stories about about Jazz, or baseball, he would maintain, but on a larger level they are stories about "us," "our history." But with Burns's simplistic and retro Black/White reading of race in America and a filmography that demonstrates an inability to see Brown people as active participants in American history, these self-describe stories about America have always felt incomplete. And while this wouldn't be a problem if his documentaries were relegated to obscure film festivals, a Burns documentary series, instead, is a well marketed media event, complete with $55 dollar coffee table books for sale at Barns and Noble, study guides available for high school history teachers, and appearances on Keith Olbermann. So the series starts on Sunday. I'll be TiVoing the episodes and will have more to say in the week or so to come, but with Ugly Betty starting again, and the finale of Top Chef coming up, no promises. For now I'll leave you with a couple of reviews and opinions: LA Weekly weighs in here (with a brief yet sympathetic nod to the controversy), Carlos Guerra opines from a Tejano perspective here, and for an especially thoughtful piece in the New Yorker (which pans the series) go here. http://brownstate.typepad.com/ken_burns_hates_mexicans/ken_burns_watch/index.html

|

|

| The sweet stuff, Zero calories developed by Tim Avila, California | ||

| The Orange County Register Tuesday, April 17, 2007 A Dana Point man develops a natural zero-calorie sweetener with an emphasis on taste. By Anne Valdespino, contributing writer First there was saccharine. Then came Sweet'N Low, followed by Equal and Splenda. And there have always been a host of natural sweeteners: stevia, sugar in the raw, agave and the favorite of the ancients, honey. But for sheer taste and texture, none could replace that gritty, grainy, shiny blast of heaven known as white sugar. Until … Zsweet? Foodies take notice: It feels like sugar on the tongue, looks crystalline in the spoon and explodes with sweetness in your mouth, leaving no chemical aftertaste. Open the packet and shake it into your hand as if it's Lik-M-Aid. You'll feel like the kid who sneaked a spoonful from the sugar bowl when no one was looking. And you might find it hard to believe that with Zsweet there's zero guilt, zero calories and zero effect on your blood sugar. Zsweet is available online and at Whole Foods, Mother's Markets, Henry's Farmers Markets and other health-food stores, and is coming soon to Costco. Though its product is made in Minneapolis, Zsweet is headquartered in San Clemente. Its inventor, Tim Avila, 41, lives in Dana Point with his wife and kids. His philosophy? Just because it's good for you doesn't mean it has to taste bad. "I call it incurring the taste sacrifice," Avila said. "We want people to have hedonistic foods that are healthy. That's what's driving the acceptance of Zsweet." Tasting is believing. Zsweet made a big splash with those who sampled it at Expo West 2007, a natural-products show held at the Anaheim Convention Center in March. Its distinctive taste comes from erythritol, which is derived from fermented glucose. The erythritol is then blended with fruit extracts as flavor enhancers, not carriers that are really sugar, Avila said. "In addition to the sweetener, sucralose in Splenda, or aspartame in Sweet'N Low, most of the powdered products have a carrier: they use dextrose or maltodextrin, and those are 99 percent sugar. Most doctors are telling diabetics to be aware of that. Dr. (Robert) Atkins, when he was alive, was saying watch even 1-3 packets a day," Avila said. The problem is that consumers think of those products as completely safe and begin to use them too freely, he added. Avila has no science degree but sounds like a scientist because he gained a lot of on-the-job training while working for a nutrition company called Metagenics in San Clemente. For years he had the know-how to make the product, but he was always looking for someone else to take it on. But in 2003 he reached a turning point. His father-in-law's Type 1 diabetes worsened; eventually he underwent amputation and kidney surgery. "It was very, very devastating," Avila said. But it gave Avila the vision and passion he needed to start Zsweet's parent company, Ventana Health Inc., in 2004. "My aunt also has diabetes, Type 2. I had this realization that this was becoming a problem, not only for adults but for children. I looked at the statistics and saw what was happening not just in the minority population (especially among Latinos) but all across this country and in other Western countries." For that reason he has helped organize Lifestyle Initiative for Education (LIFE), a nonprofit organization committed to diabetes and obesity research. About 1 percent of sales of Zsweet goes to LIFE. "We want to be able to care for not only our families but try to help everyone who is battling health concerns," he said. Zsweet may be socially aware, but it's also big business. At about $10 a box for 50 one-teaspoon packets, it's more expensive than sugar but about the same as a 1-ounce container of stevia. After Expo, Avila was fielding calls from small businesses, grocery chains and big-box retailers. He's developing a no-bulk version with higher sweetening power. "We have another branch of our company working on products made with Zsweet for diabetics," he said. Avila says his business is part science and part culinary art. "We've seen chefs using it in things like polenta and other foods, and they say it's worked fine. We have a culinary board and a chef, LaLa, who is Cordon Bleu-trained." The Zsweet Web site – there's also a Spanish version – includes recipes by Chef Lala (Laura Diaz Brown, a certified nutritionist and author of "Latin Lover Lite") for mock mojitos, hot chocolate and other goodies like strawberry cheesecake and chocolate chip cookies. There are diabetic friendly recipes, too. For Avila, it's all about taste. "I know people change habits very slowly. When I looked at other sweetener alternative options I felt they didn't taste very good and I decided to develop my own. There's no excuse for having something that doesn't taste good." Avila is confident that when consumers try his product, they'll like it. "When I walk into a Starbucks, I leave some," he says with a smile. "Guerrilla marketing!"

|

||

| ACTION ITEMS |

| Defend

the Honor Activities in Orange County, California Arlington Cemetery, Washington, DC U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services is setting up a genealogy program Corrido: Los Soldados Olvidados De La Segunda Guerra Munidial Resource information from the Defense Link Military The Worm in my Tomato by Dr. Santos C. Vega Segundo Barrio Locating our veterans buried at National & community cemeteries. |

| Defend the Honor | ||

Congresswoman Loretta

Sanchez receives a Defend the Honor button at an event at California

State University Fullerton event, November 10, 2007. Your editor and

Congresswoman Sanchez stand in front of the SHHAR display.

|

||

| Arlington Cemetery, Washington, DC | |

| Jim Carr Hispaniks@aol.com

Sends . . .Good news! "They have added some additional names I suggested to the Arlington National Cemetery (ANC) web site. Go to http://www. arlingtoncemetery.org Click on Historic Information Click on Prominent Figures in Hispanic History Editor: If you know a Hispanic/Latino buried at Arlington, please contact Jim.

|

|

| U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services is setting up a genealogy program. | |

|

As you know, Immigration is a hot issue nowadays; as a result, a new

program is being organized. I have some information that may be

news to you. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services is setting

up a genealogy program. They will provide information for a fee.

Here is what they have posted on line: This portion of the

USCIS.gov website will contain information about the future USCIS

Genealogy Program. USCIS has records, which document the arrival and

later naturalization of millions of American immigrants. If you have

an ancestor who immigrated and arrived in the United States after 1892

and was naturalized between 1906 and 1956, the future USCIS Genealogy

Program wants to help in your family history research. The USCIS

Genealogy Program will be a fee-for-service program designed to

provide genealogical and historical records and reference services to

genealogists and historians. To make a request for copies of

historical records now, contact the USCIS FOIA Program at mailto:USCIS.FOIA@dhs.gov

USCIS.FOIA@dhs.gov If you would like to contact us by email, send a note to this address: mailto:Genealogy.USCIS@dhs.govGenealogy.USCIS@dhs.gov I shall be requesting information about my great grandmothers. In my case, they were the ones who were valiente enough to leave Mexico and start new lives.

|

|

| Dec. 7 Day of Infamy: Corrido: Los Soldados Olvidados De La Segunda Guerra Munidial |

|

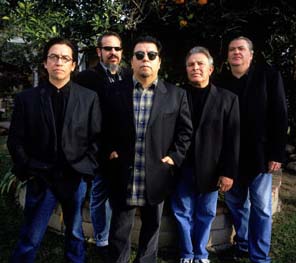

| Friends and Supporters of the

Defend The Honor Campaign: Corrido: Los Soldados Olvidados De La Segunda Guerra Munidial Ode To Our Forgotten Soldiers of WWII (see attached CD Cover) A historic educational, cultural and social justice tribute to our elders and warriors of WWII as written and sung by Los Romanticos. Listen to sound bite www.lanmusical.com/corrido. We are excited to announce the first ever CD recording of a NEW Latino and Latina WWII corrido that incorporates the history, emotions, coraje, and hope as felt and experienced by our WWII warriors and supporters of the Defend The Honor Campaign. The "artistic decisions" made by the musicians in creating the corrido are of the highest quality and pay deep respect to our WWII elders and their families. Our history is being recorded by our own gente in books, research articles, voting booth, teatro and always through the use of music and the corrido. You can join all of us celebrate and experience the new corrido by purchasing one or more CD's for yourself, friends, organization, library or school. It is a keepsake memento in honor of all Latinos and Latinas who served our country before, during and after WWII Please contribute to our "WAR" effort by mailing a $20.00 check payable to: Pepe Villarino 5775 Amarillo La Mesa, CA 91942 Sent by Gus Chavez guschavez2000@yahoo.com Defend The Honor Campaign |

|

| Resource information from the Defense Link Military | |

A suggestions for displays, include the Military Academies cadets and graduates. The web site below included the names of cadets from the four academies plus AF Brig. Gen Maria Owens. John M. Molino, acting undersecretary of defense for EO and their BIOS. You can search the Defense News archives by using the google search "Defense News" and clicking the News archive folder. http://www.defenselink.mil/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=25303 http://www.defenselink.mil/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=25295 Sent by Rafael Ojeda RSNOJEDA@aol.com |

|

|

The

Worm in my Tomato |

|

|

Thousands of Mexican Repatriates of the 1930s no

doubt can relate to the suffering and hardship endured by the Vega

family in the story. Indeed, the story shows how the Repatriation

prompted personal, cultural, psychological and theological decisions.

Is the experience of the

Repatriation to be repeated again? Abrazo Enterprises E-Mail: abrazo@qwest.net

|

|

| Segundo Barrio | |

| A common theme in Chicano

history and literature has been identification with place in form of

the barrio and the struggle to preserve memory. Generally,

Mexicans were poor and lost the battle to developers, i.e.,

Sonoratown, Chavez Ravine. Echo Park in LA, Humbodlt, Lincoln Park,

the Near West Side in Chicago and countless other barrios across the

nation. The great Lalo Guerrero advertised the struggle in

Tucson with his song Barrio Viejo. A group of activists in

El Paso have recently banded together in El Paso to save one of the

oldest barrios in the U.S. --Segundo Barrio as it is known. Led by

activists such as Yolanda Leyva and Donald Romo the community is

taking on Mexican and U.S. mega investors who want to wipe out

"blight" and convert the space into profit making "Taco

Bell" much like what has happened in San Diego's Old Town. With

it goes memories of the Magonistas, Teresa de Urrea etc.

Unfortunately, from my vantage point, few Mexican Americans have

supported the fight. It has fallen to the same few. Rudy Acuña Sent by Dorinda Moreno |

|

| Locating our veterans buried at National & community cemeteries. | |

| From: jaq1000@verizon.net Mr. Ojeda, Rafael y Mimi Thank you for including me in your emails, we greatly appreciate you continued drive and efforts on behalf of all Hispanic Veterans and their families. This is one of the Websites Col. Jim Carr is utilizing. Permit me to tell you a little more about the work that Col. Carr has been doing on the Arlington Cemetery Project. He started this project over a year ago and has done a lot of research, met with VA and Arlington Cemetery Officials. As our HWVA Historian, he decided to take on the most known of all Veterans Cemeteries, which is Arlington. With the support of key HWVA Officers, such as our HWVA past national Executive Director, General Erwin “El Sueco” Huelswede, he is still working with officials to identify our Warrior Heroes and is still working with them to get it right on their Website ID listings of Minorities. As you are aware, having gone through many projects yourselves, this is a never ending process. Jim has established great rapport with these officials and it is only a matter of time before the officials get it right. It is also a very frustrating process, but Jim is determined that once this project is accomplished, the HWVA will then tackle additional Veteran Cemetery issues. Jim also found out that many of our Hispanic Hero Warriors, be they men or women are not identified as Hispanic for one simple reason, they do not have a Hispanic surname due to ancestral or marriage. And there are other reasons, for example at Arlington, they buried several parts of bodies in one grave because it was difficult to identify which body part belonged to who and they may have even missed a person because they really didn’t know who or how many were actually blown up together. This is where his research really becomes important because this is one of his biggest research hurdles. Government staff as you know is only dedicated to what they can identify, few do background research, which means that these veteran identity sites may or may not list all of our Veteranos or Veteranas. We greatly appreciate you keeping us in the loop of your emails. Semper valor y honor!!! Jess Quintero HWVA Secretary jaq1000@verizon.net 202-439-8028 From: RSNOJEDA@aol.com [mailto:RSNOJEDA@aol.com] My Dear Friends, Not only does the VA keep the names of those veterans buried in our National Cemeteries, but in any community cemetery as long as the VA delivered a VA marker. The web site below gives instructions on how to find them both in English and in Spanish. Thanks. Rafael Ojeda http://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/j2ee/servlet/NGL_v1 |

|

| EDUCATION |

| The

State of Education in California Youth, Identity, Power, The Chicano Movement CA Philanthropy Roundtable Speakers' Bios & contact info. Full Ride College Application - please share! Scholarships Directory UH Center for Mexican American Studies - Visiting Scholars Program 2008 White House Internship Program Latino Awards, Fellowships, internships, and research grants |

| The

State of Education in California, Source: Assemblyman Jose Solorio E-newsletter |

|

Nearly

200 people attended our Education Town Hall meeting, "The State

of Education in California," that I hosted on November 14th in

Santa Ana. The meeting brought educators, administrators and

community leaders together to discuss the results of recent studies

regarding California's educational system and ways to finance,

reform, and improve schools. I was

impressed that more than 30 community members provided public

testimony and many people expressed an interest in holding

additional town hall meetings to discuss education in California. Nearly

200 people attended our Education Town Hall meeting, "The State

of Education in California," that I hosted on November 14th in

Santa Ana. The meeting brought educators, administrators and

community leaders together to discuss the results of recent studies

regarding California's educational system and ways to finance,

reform, and improve schools. I was

impressed that more than 30 community members provided public

testimony and many people expressed an interest in holding

additional town hall meetings to discuss education in California.

Thomas Timar, Ph.D., research director for the Governor's Advisory Committee on Education Excellence and professor of education at the University of California, Davis, provided a presentation of the 23 studies that comprise Getting Down to Facts. These studies were completed under the auspices of the Institute for Research on Education Policy & Practice (IREPP) at Stanford University and can be viewed online at www.irepp.net. Getting Down to Facts provides a groundbreaking analysis of the resources needed to adequately educate a child, as well as how our state's educational system can be reformed. I hosted the town hall meeting because it is important for our communities to have an understanding of this information so they can help improve our schools. I also wanted to hear from you about how you think the state's education system should be improved. I also want to invite you to our Anaheim District Office's 1st Annual Holiday Party on Tuesday, December 18, from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m. Refreshments and hors d'oeuvres will be provided. Our district office is located at 2400 E. Katella Avenue, Suite 640, Anaheim (immediately north of Angel Stadium). Let's celebrate our first successful year in the Legislature and discuss ideas for 2008. To RSVP or for more information, please contact Mayela Montenegro at (714) 939-8469 or by email at mayela.montenegro@asm.ca.gov. As always, please do not hesitate to contact me at Assemblymember.Solorio@assembly.ca.gov if you have any ideas or need assistance with any other matters. Sincerely, E-Newsletter www.assembly.ca.gov/solorio |

|

| YOUTH, IDENTITY,

POWER, The Chicano Movement by Carlos Muñoz, Jr. Ph.D. UC Berkeley |

|

|

Revised and Expanded Edition: YOUTH, IDENTITY, POWER The Chicano Movement By Carlos Muñoz, Jr. An essential record of the Chicano movement and an important addition to the history of the American social protest.' -San Francisco Chronicle' A very important and powerful book, documenting American History·without question, one of the lodestones in reference to the 'movimiento'.' -- Luis Valdez, founder of the Chicano Teatro Campesino' The first major book on the Chicano movement by one of its leaders, who is also a first-rate scholar. Youth, Identity, Power is certain to be a benchmark for all future work on the subject. An important contribution to the history of the 1960s,

it· should be

required reading.'- Clayborne Carson, Stanford University. In the

revised edition of YOUTH, IDENTITY, POWER (Verso, distributed by W.W.

Norton, PB, $23.95), scholar-activist Carlos Muñoz, Jr extends his

classic study of the 1960s Chicano civil rights movement with a

groundbreaking after word that brings the imperative of multiracial

democracy to a new level of clarity. This analysis of Chicano thought

and struggle in America bridges the movement's involvement between

civil rights, social progression and the ever-pertinent history of

Mexican-American tensions. Muñoz chronicles the evolution of the

1960s' Chicano radical leaders from their student activist precursors

of the 1930s, and evaluates how the progress of their combined labors

have formed the many American Latino communities of today. The

contribution of such a necessary study from one of the influential

leaders of the Chicano movement provides for an empowered and crucial

estimation of the struggles confronting the burgeoning Latino

community.

|

|

| CA Philanthropy Roundtable Speakers' Bios & contact info. | |

Here is a great resource for Keynote Speakers. Many of these or our "Orgullos Hispanos" that we know of. As you can see many of them are "Experts and Advocate" for our Children k-20 education. Hopefully this will be a great resource info for you and your organizations or to network with other organizations that may call on you to recommend "keynote speakers" for their events. Rafael Ojeda RSNOJEDA@aol.com http: www.philanthropyroundtable.org/files/SantaMonicaBios.doc

|

|

| Full Ride College Application - please share! | |

Cynthia Robinson wrote: Please share noting that HBC’s will also consider applications from any ethnicity….not just Blacks…. Do you know any high school seniors that will graduate by May 2008, and would like to attend a Historically Black College or University? The Tom Joyner Foundation is offering "full ride" scholarships for graduating high school seniors. Deadline for Applications (attached) is January 18, 2008. http://www.blackamericaweb.com/site.aspx/foundation/fullride Sent by rgrbob@earthlink.net

|

|

| Scholarships Directory | |

|

Our office received a 2007-2008 scholarship directory for Latino students; below is the website to access the directory online. The directory is for high school, undergraduate and graduate students. Please forward this information along: www.latinocollegedollars.org

Diann G. Maldonado Cosme |

|

UH Center for Mexican American Studies - Visiting Scholars Program, 2008-09 |

|

|

Source:

"Carlos Munoz, Jr." <cmjr@berkeley.edu>

Center for Mexican American Studies Office of the Director The Center for Mexican American Studies (CMAS) at the University of Houston is soliciting applications for its Visiting Scholars Program for the 2008-2009 academic year. All interested scholars from relevant disciplines are encouraged to apply. Visiting Scholars receive a salary appropriate to rank and are expected to be in residence during the academic year. Priority consideration will be given to applicants who

a.

have specializations in both Mexican and Mexican American Studies

b.

may have an interest in remaining at the University of Houston in a

tenured or tenure track position after their one year residency as the

CMAS Visiting Scholar is completed.

Applicants

must have earned a PhD and submit the following materials.

a. current resume b. two page description of a proposed research project that will undertaken while in residence c. three letters of recommendation Materials may be submitted via electronic mail to ladame@uh.edu. The deadline for submission of materials is April 15, 2008. More information about the CMAS Visiting Scholars Program can be obtained by visiting the following website www.class.uh.edu/CMAS. The University of Houston provides equal treatment and opportunity to all persons without regard to race, national origin, sex, age, disability, veteran status, or sexual orientation except where such distinction is required by law. This statement reflects compliance with Titles VI and VII of the Civil Right Act of 1964 and Title I of the Educational Amendments of 1972 and all other federal and state regulations. Learning. Leading. 323 Agnes Arnold Houston, TX 77204-3001 713/743-3136 Fax: 713/743-3130 Sent by Dr. Roberto Calderon beto@unt.edu

|

|

| 2008 White House Internship Program | |

|

Dear LULAC Friend: Please click on the following link to download the 2008 White House Internship Program application (PDF Format). Also, please feel free to forward the application to anyone you know who is interested in interning at the White House next summer or fall. http://my.lulac.org/site/R?i=QD3gSmHOFlpQDQMa2QKOVw Application packet deadlines are: February 26, 2008, for Summer 2008 Term June 3, 2008, for Fall 2008 Term To be eligible, an applicant must be: At least 18 years of age on or before the first day of the internship Enrolled in an undergraduate or graduate program at a college or university, or have graduated the previous semester, and is a United States citizen For more information, please go to: http://my.lulac.org/site/R?i=gv2G28IffC1jzuMblZfLSQ . Thank you. Sincerely, Rosa Rosales LULAC National President Sent by Larry Luera luckylarry77@earthlink.net

|

|

Many Latino Awards, Fellowships, internships, and research grants Sent by Roberto Calderon, Ph.D. beto@unt.edu |

| Latino Studies Fellowship Program | |

| Sponsor: Smithsonian Institution SYNOPSIS: Fellowships provide opportunities for U.S Latino predoctoral students and postdoctoral and senior scholars to conduct research related to U.S. Latino history, art and culture in association with members of the Smithsonian professional research staff, and utilizing the resources of the Institution. Predoctoral fellowships offer a stipend of $25,000 per year plus allowances and postdoctoral and senior offer a stipend of $40,000 plus allowances. Deadline(s): 01/18/2008 Title: Latino Studies Fellowship Program E-mail: siofg@si.edu http://www.si.edu/ofg/Applications/LSFELL/LSFELLapp.htm |

|

| Harold T. Pinkett Minority Student Award | |

| Sponsor: Society of American Archivists SYNOPSIS: The sponsor provides an award to recognize minority undergraduate and graduate students, such as those of African, Asian, Latino or Native American descent, who through scholastic and personal achievement manifest an interest in becoming professional archivists and active members of the sponsor's organization. Deadline(s): 02/28/2008 Title: Harold T. Pinkett Minority Student Award E-mail: info@archivists.org Web Site: http://www.archivists.org/recognition/awards.asp Program URL: http://www.archivists.org/governance/handbook/section12-pinkett.asp |

|

| National Museum of American History--Lemelson Internships Archival Internships | |

| Sponsor: Smithsonian Institution SYNOPSIS: The sponsor offers full time, ten week, archival internship opportunities for graduate students each summer. The internship stipend is $4,000 plus a travel allowance. The stipend is not taxed and housing and benefits are not provided. Deadline(s): 03/03/2008 Title: National Museum of American History--Lemelson Internships Archival Internships E-mail: oswalda@si.edu Program URL: http://invention.smithsonian.org/resources/research_interns.aspx |

|

| Phillips Fund Grants for Native American Research | |

| Sponsor: American Philosophical Society SYNOPSIS: The sponsor provides support for research in Native American linguistics, ethnohistory, and the history of studies of Native Americans in the continental United States and Canada. Eligible applicants are younger scholars who have received the doctorate, and graduate students. Grants average $2,500 for one year. Deadline(s): 03/03/2008 Title: Phillips Fund Grants for Native American Research E-mail: LMusumeci@amphilsoc.org Program URL: http://www.amphilsoc.org/grants/phillips.htm |

|

| Mini-Grants | |

| Sponsor: Humanities Texas SYNOPSIS: The sponsor provides Mini-grants of up to $1,500 to support public programs that draw upon the humanities to increase understanding of any aspect of human experience. These grants are available for both program planning and implementation. DEADLINE NOTE Applications should be submitted no later than six weeks prior to a project's start date. Title: Mini-Grants E-mail: grants@humanitiestexas.org Web Site: http://www.humanitiestexas.org/grants/applications/minigrant.pdf Program URL: http://www.humanitiestexas.org/grants/applications/guidelines.pdf |

|

| Community Project Grants | |

| Sponsor: Humanities Texas SYNOPSIS: The sponsor provides community project grants for public humanities projects such as lectures, seminars, and conferences; book and film discussions; interpretive exhibits; site interpretations; chautauquas; town forums and civic discussions; and K-12 teacher training workshops. Deadline(s): 02/15/2008 08/15/2008 Title: Community Project Grants E-mail: grantsr@humanitiestexas.org Web Site: http://www.humanitiestexas.org/grants/applications/community.pdf Program URL: http://www.humanitiestexas.org/grants/applications/guidelines.pdf DEADLINE NOTE The deadlines for receipt of letters of intent/draft applications are: February 15 and August 15 annually. The deadlines for receipt of full applications, if invited, are March 15 and September 15 annually.

|

|

| BILINGUAL EDUCATION |

| Latino/a History, For Kids!!! Hispanic American Theater |

| Latino/a History, For Kids!!! | |

|

A new website has been launched to promote LATINO/A HISTORY FOR KIDS!!! The future of our children depends on our ability to teach them to be culturally sensitive, open minded, and to become people of conscience. They can only love and respect OTHERS if they love and respect THEMSELVES... A series of children's activity books have been developed to teach kids about Cesar Chavez and the UFW as well as what it means to GROW UP LATINO/A IN THE USA. These books use word finds, coloring pages, writing activities, and other fun activities to teach kids vocabulary, pride, and Latino history!!! If you are interested in viewing these books (or purchasing them) please visit http://www.latinohistory4kids.com or contact Angel R. Cervantes at acervant@crsassociates.net for more information. Angel R. Cervantes, a resident of the San Fernando Vally, has taught elementary school for over 10 years. He is also an adjunct instructor of History at Glendale Community College. Currently, he is serving as a Commissioner for the City of LA. Sent by Howard Shorr howardshorr@msn.com

who writes that he has not seen the books. |

|

| Hispanic American Theater | |

|

The roots of Hispanic theater in the United States reach back to the Spanish and Native American heritage of Hispanics. They include the dance-drama of Native Americans and the religious plays and pageants of medieval and Renaissance Spain. During the Spanish colonization of Mexico, Catholic missionaries used plays to help convert the native peoples of Mexico to Catholicism. Plays were later used to teach mestizo (those of mixed Spanish and Native American heritage) Mexicans the mysteries and rituals of the church. In the 1600s and 1700s, a hybrid religious theater developed. These plays combined the music, colors, flowers, masks, and languages that were a part of the native cultures with the stories of the Bible. In Mexico and the American Southwest, these plays eventually moved farther and farther from their religious origins. In the end such plays were banned by the Catholic Church. They were not allowed on church grounds or in church festivals. Because of this separation from the church, such plays became part of the folk culture. The community put on the plays without the help and support of the church. Hispanic Drama in the United States In 1598 Spanish explorer Juan de Onate led a group of Spanish colonists into what is today New Mexico. The colonists brought with them folk plays from Spain and Spanish America. In their camps Onate's soldiers would entertain each other by making up plays based on their experiences on the journey. They also put on a popular Spanish folk play. Moros y cristianos was a heroic play about how the Spanish Christians defeated the Islamic Moors in northern Spain and drove them off the Iberian Peninsula. This play eventually spread throughout Spanish America. It has even been performed in the twentieth century in New Mexico. Moros y cristianos influenced many later Hispanic epic plays about war and conflict. As early as the late 1700s, the Hispanic folk

theater in the United States developed into a theater of

professionals. This usually happened in areas with large Hispanic

populations.

At first, touring groups from Mexico

traveled to California where they performed melodramas and musicals.

In the mid-1800s regularly scheduled steamships made

it easy for these groups to put on plays in

San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

Eventually, professional theater troupes

could be found in the Southwest, New

York, Florida, and even the Midwest. Around the time of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, thousands of Mexican refugees settled in the Southwest and the Midwest. This influx of immigrants sparked an increase in theatrical activity. During the decades of revolution, many of Mexico's greatest dramatic artists and their companies came to the United States. They came to tour and take up temporary residence. However, some stayed permanently. These Hispanic groups and others already established in the United States toured cities in Florida, New York, the Midwest, and the Southwest. the most popular cities were San Antonio and Los Angeles. By the 1920s Hispanic theater had become big business.

Editor: I have

searched through both the Elementary School Edition and Secondary

School Edition (also 4-volume), and have found the information

accurate, authoritative, and refreshingly unbiased. For more

information, call 215-321-7742 or email: afriampub@aol.com

or write:

|

|

| CULTURE |

| La

Cancionera de los Pobres, Lydia Mendoza Tejana singer dies Hollywood's Most Acclaimed José-Luis Orozco is an author and recording artist History of the Pinata Hispanic American Theater |

|

|

|

| Given the gringo media's

narrow focus on U.S. Latinos from a purely immigration angle, it's

easy to forget Brown people, and in particular Mexican Americans,

have been mixing it up in the American cultural landscape since

before there even was a so-called "America." As those

wacky Mechistas like to say, "we didn't cross the border, the

border crossed us." One of the greats of the last century died

last week, Lydia Mendoza, age 91, a Tejana singer hugely influential

on both sides of the border since her first recordings back in the

1930s.

From her AP obit: "Mendoza scored her first big hit, Mal Hombre (Evil Man), in the 1930s and became one of the era's first Mexican-American superstars by singing to the poor and downtrodden.Mendoza recorded more than 200 songs on more than 50 albums, including boleros, rancheras, cumbias and tangos for such labels as RCA, Columbia, Azteca, Peerless, El Zarape and Discos Falcon. In addition to pursuing a solo career, she also enjoyed performing with her family. Mal Hombre, released in 1934 on the Bluebird label, became a hit on both sides of the border and was her signature song." In 1982, she became the first Texan to receive a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship and in 1999, she was awarded the National Medal of Arts. Back in the day, I used to work as the assistant for the Theater Program for the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center in San Antonio (this when the Center actually had dynamic Chicano programming and nothing like the culturally bankrupt institution it is today. More on that sad story maybe later.) The Theater Program commissioned a play on Lydia and it was written by Anthony J. Garcia and included live music and many of her songs. As with most people my age, I knew very little about Lydia. And so while the play taught me the facts of Mendoza's life and exposed me to her poignant, sentimental, powerful music, it was the crowds of Raza flocking to the show that made me aware of Mendoza's importance and cultural impact. For more than a month -- three nights a week and a Sunday matinee performance -- the shows sold out. Lydia herself attended once. By then she was nearly 80, partially debilitated by a stroke, but insisted on attending in one of her signature large and fluffy colorful dresses she wore when performing. Her hair was swept up 1940s style. She waved to the crowd as they gave her a standing ovation. Unfortunately, another lesson learned watching the rich exchange between talented performer and knowledgeable and appreciative audience was witnessing another example of another Secret History revealed, if only for a moment, and, equally frustrating, only within the confines of the Guadalupe Theater. The careers and talents of performers like Josephine Baker and Billie Holiday are not only well-known to most Americans, but acknowledged as active participants and contributors to the larger story of American popular music. If anyone can lay claim for equal significance to the American pop canon it is Lydia Mendoza. Unsurprisingly, her story remains on the margins of our national cultural identity. Below is an article published in the Los Angeles Times, Monday, December 31, 2007 Lydia Mendoza - Tejano pioneer Lydia Mendoza, an early star of Mexican American music whose passionate, despairing songs about working-class life on both sides of the border made her a trailblazer for the Tejano genre, has died. She was 91. Ms. Mendoza, whose singing career spanned more than 60 years, died Dec. 20 of natural causes at Nix Medical Center in San Antonio, according to reports. In 1999, Texas Monthly magazine called her the "greatest Mexican American female performer ever to grace a stage." The words for her first hit came from her girlhood collection of gum wrappers that contained lyrics. She put the words from one wrapper to a tune she had heard in concert in Mexico and first performed "Mal Hombre" (Evil Man), a song about false-hearted lovers, when she was 10. After Ms. Mendoza recorded the tango in 1934, it became a major hit in the Spanish-speaking community and started her career. Accompanied by her signature 12-string guitar, Ms. Mendoza often sang about hardship and rejection in a powerfully sincere style that reflected the music developing along the U.S.-Mexican border. Her trilling voice earned her the nickname "La Alondra de la Frontera," or Lark of the Border. In 1935, she married shoemaker Juan Alvarado and continued to perform in an era when wives usually gave up their careers. By 1940, Ms. Mendoza had recorded more than 200 songs in a wide variety of musical styles that included boleros, rancheras and cumbias. She wrote many of them herself. She performed at the 1977 inauguration of President Jimmy Carter and in 1999 received a National Medal of Arts, which recognizes outstanding contributions to the field. At the White House medal ceremony, President Bill Clinton praised her for bridging "the gap between generations and cultures." She was born in Houston in 1916 to Francisco and Leonor Mendoza. Her family had come from northern Mexico, and she and several siblings grew up moving between Mexico and Texas. In 1928, her father answered an ad in a San Antonio newspaper placed by a New York company looking to record Spanish-language musicians. In a hotel room, the family recorded its first record and was paid $140 for 20 songs. Still needing to find regular work, the Mendozas moved to Michigan to work in the vegetable fields. Upon hearing the family perform, co-workers encouraged them to play in town, and they spent several years working and performing in small restaurants. Back in Texas in the early 1930s, the family often played for tips at an outdoor market in San Antonio, where the host of a Spanish-language radio show heard Ms. Mendoza sing. She was soon performing on the radio for $3.50 a week. While the radio show made her popular in the region, the repeal of prohibition in 1933 created opportunities for cantina musicians. Eventually, the family began touring throughout the Rio Grande Valley in southern Texas. Ms. Mendoza performed solo while her siblings sang together and put on a variety act. Even after having three daughters, Ms. Mendoza kept performing, but gas rationing during World War II temporarily ended her touring. In 1947, she returned to the road, but the family group broke up in 1952 after her mother died and a sister married. Although her status as an idol had peaked during the 1950s, Ms. Mendoza continued recording and touring as a solo act until a series of strokes forced her to retire in 1988. After her husband died in 1961, she married another shoemaker, Fred Martinez, in 1964, and they moved to Houston, where she often performed in small nightclubs. She pulled from a repertoire of 1,200 songs that spanned almost 100 years. Copyright 2007 SF Chronicle Here's an NPR link which features an excerpt from Lydia's autobiography as well as links to some of her songs; info here and here on Yolanda Broyles-González's book on Lydia; a fine blog entry by San Antonio Express New music writer Ramiro Burr on Mendoza's life and influence; this Josh Kun piece on the singer, complete with thoughtful analysis as well as a reference to the very cool Los Super Elegantes punk rock cover of Mal Hombre; song samples from Mendoza's Arhoolie CD here; and an Express News article on her burial yesterday at San Fernando Cemetery in San Antonio. TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://www.typepad.com/t/trackback/2345006/24455148 Information sent by Roberto Calderon and Armando Rendon, Ph.D. armandorendon@sbcglobal.net

|

|

| “HOLLYWOOD‘S MOST ACCLAIMED” | |

|

For More Information,

Contact:

Gato Loco Productions

|

|

|

|

|

|

Born in Mexico City, José-Luis Orozco grew fond of music at a young age, learning many songs from his paternal grandmother. At age 8, José-Luis became a member of the Mexico City Boy’s Choir, and traveled the world visiting 32 countries in Europe, the Caribbean, Central and South America. It was from his tour around the world that he gained the cultural knowledge he now shares with children through his books and recordings. At age 19, José-Luis moved to California in search of the American dream. He went to college and earned his Bachelor’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley and a Master’s degree in Multicultural Education from the University of San Francisco. José-Luis

Orozco dedicates himself to what he truly enjoys – singing for

children. He has built a successful career as a children’s author,

songwriter, performer and recording artist. He has recorded 13

volumes of Lírica Infantil, Latin American Children’s

Music, and written three successful, award winning books, De

Colores and Other Latin American Folk Songs for Children

(Dutton 1994), Diez Deditos – Ten Little Fingers

(Dutton 1997), and Fiestas (Dutton 2002). CD’s of

De Colores, Diez Deditos and Fiestas, accompany

these colorful books and present an extraordinary bilingual

collection of songs, rhymes, tongue twisters, lullabies, games and

holiday celebrations gathered from Spanish-speaking countries. In

2003, José-Luis released an exciting video and DVD entitled Cantamos

y Aprendemos con José-Luis Orozco – Singing and Learning with José-Luis

Orozco, filled with live action, animation, and Latino

flavor that motivates children to learn about the Spanish language

and the rich tradition of Latin American children’s music.

|

|

| History of the Pinata | |

| Can be found on website of MEXICO CONNECT http://www.mexconnect.com/mex_/travel/wdevlin/wdpinatahistory.htm Sent by Dr. Armando A. Ayala DrChili@webtv.net Editor: Mexico Connect is new to

me, we worth searching. It is made up of articles by diverse

writers on varied subjects of interest to Mexico. |

|

| BUSINESS |

Sánchez Family Foundation $10 Million Gift to TAMIU

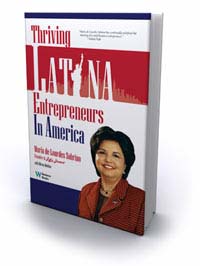

College of Business Thriving Latina Entrepreneurs

in America

|

|

|||

Texas A&M International University’s College

of Business Administration has been named the recipient of a $10

million gift from the A.R. “Tony” and María J. Sánchez Family

Foundation. The Gift will be used to establish an endowment fund for the

University’s College of Business Administration for its support,

programming, activities and improvements. The Sánchez’ said the Gift exemplifies the A.R. “Tony” and

María J. Sánchez Family Foundation’s commitment to effecting

social change and improving the quality of life for residents of South

Texas and the border. “Our family has deep roots here and a great affection for our

hometown. Through our Foundation, we are able to return some of

our good fortune to the people and place that we truly cherish.

We are delighted to be able to give the College of Business

Administration the ability to grow and excel further,” said Tony Sánchez.

His wife, María “Tani” Sánchez, noted, “By doing so, we

strongly believe that we are effecting lasting social change here and

providing a catalyst for an improved quality of life in South

Texas.” Dr. Ray Keck, TAMIU president, said the impact of the latest Sánchez

gift is indeed life-changing for the young University. “We have always been much-blessed by the partnership of the Sánchez

family, but this gift is absolutely monumental in purpose and scope.

While we feel this remarkable family’s presence daily here at TAMIU,

this generous gift extends their vision beyond our imagination. All

young universities like TAMIU dream of such a partner and we are so

fortunate that they share and affirm our vision of higher education

for South Texas,” Dr. Keck said. The Sánchez Family has played a pivotal role in the University’s

development and underwritten a number of initiatives that have greatly

improved the quality of life for numerous South Texas residents. True to their commitment to investing in the future of Texas and

effecting social change, the Sánchez Family has awarded 86 full-time

students, many of them first-generation college attendees, with

scholarship gifts providing books, fees, and tuition for TAMIU

undergraduate program completion. Known as the Sanchez Scholars, this

select group is made up of four cohorts. In addition, the Sánchez Family’s funding of TAMIU’s College of Business Administration’s Business Technology Center and Trade Room has enabled students’ access to the world of financial information in milliseconds, bringing business education to a new level at the University.

The Value-Investing

Trading Room opened in September 2007.