Miguel

León-Portilla,

the renowned Mexican ethnographer, tells us that “the

literary production of ancient Mexico was far more prolific than is

generally recognized”

(173). I would not come to know this until 1969, the year I read León-Portilla’s

work; the year I began my study of Backgrounds of Mexican

American Literature (first study in the field) at the University

of New Mexico.

León-Portilla’s

work figured prominently in my research as I sought to create a

taxonomical scaffold for the history of Mexican American literature.

What started out as the organization of a course in Mexican American

literature led to my research in Backgrounds of Mexican American

Literature and has turned out to be a passion in my academic

career which now spans almost 60 years.

In

the summer of 1969 I was on leave from New Mexico State University

in Las Cruces as a Teaching Fellow in the English Department at the

University of New Mexico at Albuquerque when Louis Bransford,

recently appointed head of the embryonic Chicano Studies program at

UNM, asked me to put together a course in Chicano literature–a

term that would gain prominence from that year on. Of course, I

assured him, naively thinking

the task would be like organizing any

other course. Little did I know what lay in store for me.

As

a consequence of that course I came to realize what a trove of

literature Mexican Americans had produced since 1848 when Mexico was

dismembered and more than half its territory seized by the United

States as plunder of the war against Mexico (1846-1848). As the

first literary history in the field, Backgrounds of Mexican

American Literature would only be a starting point. Addressing

the “New

World”

roots of Mexican American Literature, I wrote:

The

taproots of Mexican American literature are not only planted in the

Hispanic literary tradition, which reaches back to the Spanish

peninsula and to the heart of the Mediterranean world, they are

planted also in the literary soil of the new world (17).

Adding

that:

We

should bear in mind, as Willis Barnstone reminds us in his

Introduction to Ignacio Be-rnal’s

work on Mexico Before Cortez (1963), that “the

Mexican [American] has a profound sense of cultural continuity

extending back into [Mexico’s]

prehistory”

(18).

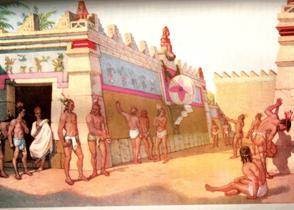

It’s

important to remember that the Spaniards did not bring “civilization”

to Mexico. When Cortez passed between the high volcanos of Popocatepetl

and Ixtazihuatl on his way to the valley of Mexico (Tenochtitlan),

he was traveling in the land of a people who had already achieved a

high state of civilization, its grandeur no less diminished when

compared to the civilization of the European invaders.

The

Aztecs were expert horticulturalists. In fact, according to Foster

and Cordell, crops of Meso-American origin, “sustain

a large proportion of the Earth’s

present population”

(xiv). And in The Columbian Exchange, Alfred Crosby maintains

that the fact that “American

crops thrived in adverse conditions gave them a critical role in the

world population boom of the past two centuries; such a boom

probably could not have occurred without them”

(cited in Foster and Cordell, xiv-xv).

There

were grand botanical gardens in Mexico long before the Europeans had

them. Pre-conquest Mexico was not a land of savages and brutality as

depicted in historical accounts. It was, in every sense of the word,

a developing nation. Bernal Diaz del Castillo, Cortez’

chronicler of the True History of the Conquest of New Spain,

captured the wonder of the new world when he wrote:

And

after we saw so many cities and towns built on the water, and other

cities on the surrounding land, and that straight and level causeway

which entered the city, we were amazed and said that it was like the

enchanted places recounted in Amadis de Gaula, because of the

great towers and buildings which grew out of the water, all made of

stone and mortar, and some of our soldiers even asked whether what

they saw was not a dream, and so no wonder that I write in this way,

for there is so much to ponder in all these things that I do not

know how to describe them. We saw things never heard or dreamed

about before”

(LXXXVII)

Consider

Bernal Diaz’

observation compared to 18th century comments that

characterized the indigenous peoples of the Americas as

brutish savages still using crude implements of bone and stone,

incapable of the organization and marshaling of resources necessary

for building cities or maintaining imperial institutions (Borah and

Cook, 1-2).

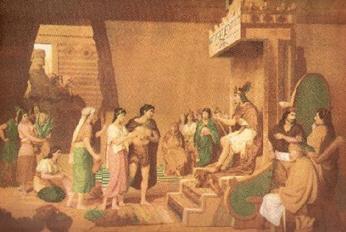

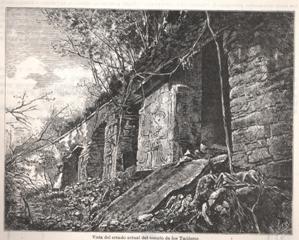

The

New World ancestors of Mexican Americans were not only a highly

cultured and highly urban people, they were a literate people as

well. As Stan Steiner put it, “no

people in the New World have an older written history than the

Mexican Indians”

(24). Indeed, the Olmec writing system, for example, dates back to

at least 600 BC. Before the arrival of the Spaniards in Mexico there

existed a rich autochthonous literature. Unfortunately, much of the

pre-Columbian literature of Mexico was destroyed by the fiery

antipathy of Spanish clerics who incinerated what Indian writing

they could get hold of because to them it represented a pagan

tradition spiritually opposed to their own. The indigenous “texts”

were destroyed because they were thought to be heretical products of

the devil with their iconographic / pictographic figures and

symbols. At the time, Bishop Landa of Yucatan has been quoted as

saying: “We

found a large number of books of these characters [codical writing],

and as they contained nothing but superstition and lies of the

devil, we burned them all”

(Peterson, 240).

The literature of the vanquished is always the first victim

of any conflict, especially cultural conflicts. Though Fray Juan de

Zumarraga and Fray Diego de Landa sought to extinguish those “heretical

texts,”

some of them escaped the fire and were later rendered into western

writing. Fortunately, the Popol Vuh, the Mayan bible or the

Quiché

Book of Being, was one of those works which survived and

which has been translated into Spanish and English. The Mayan book

of the Jaguar Priest, the Chilam Balam, and the Annals of

the Xahil also survived. In all, fourteen codices survived, but

ironically they are reposited today elsewhere than in Mexico. Only

copies exist there. Some of the works of King Nezahualcoyotl (d.

1472) of Texcoco, the poet-King or the David of the Aztecs, survived

and have also been translated into Spanish and English. At every

turn, the Spanish colonial administration in Mexico sought to

suppress the intellectual productivity of the indigenous people.

After the conquest, Fernando de Alva Ixtilzo-chitl wrote of

the exploits of his ancestor with the same name, Ixtilxochitl,

Prince of Texcoco, during the conquest, translating the Aztec

writing into Spanish. Today, the quality of pre-Hispanic literature

may be surveyed in a number of works including The Broken Spears:

the Aztec Account of the Con-quest of Mexico (Beacon Press,

1962) by Miguel León-Portilla,

or in his other work on Aztec Thought and Culture (University

of Oklahoma Press, 1969). Other works on New World literature

include Daniel G. Brinton’s

Ancient Nahuatl Poe-try (Philadelphia, 1890), John H. Cornyn’s

Aztec Literature in the XXVII Congress International des

Americanistes (Mexico, 1939), Angel Maria Garibay-K’s

Historia de la Literatura Nahuatl (Mexico, 1935), and Antonio

Peñafiel

(Editor), Colleccion

de Documentos

Para la Historia de Mexico, 6

Volumes (Mexico,1897-1903).

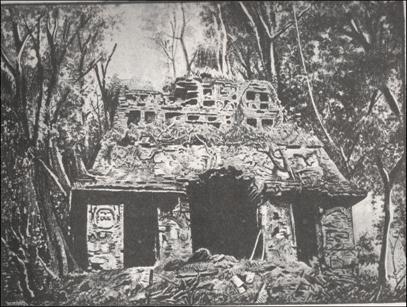

The

pre-Columbian literature of Mexico consisted entirely of codices;

that is, a long, screen-like, accordion-pleated parchment of animal

skin or amate

(paper) made smooth in a solution of lime with “writing”

on both sides. (Post-conquest codices were constructed of cloth.

Paper was used in Aztec rituals and was an important item of trade

and tribute in pre-Cortesian Mexico. The town of Cuernavaca paid its

tribute in paper to the Aztec emperor).These codices dealt with a

variety of subjects. The Mexicans had books on agri-culture, botany,

law, magic, medicine, poetry, sports, songs, etc. For example, the Tonalamatl

was the sacred almanac which recorded the tonalpohualli, the

count of souls in the year. The scribes were called tlacuilos,

and they recorded on codices the most minute events of Mexican life.

While

the Mexican languages were essentially phonetic in utterance they

were rendered on codices in ideographic form, comparable to Chinese

and Japanese writing. A codex could be opened and read in a number

of ways. Though relatively little pre-Hispanic Indian literature

survived the Spanish holocaust, Peterson opined hopefully:

there

is always the possibility that some ancient codex lies forgotten in

a trunk in some attic in Europe, or is a jealously kept secret in

some town in Mexico, or is hidden under dusty files in a library,

and will eventually add to our store of information (Op. Cit.,

241).

One

of those ancient codices, the de la Cruz-Badiano Codex,

albeit written in 1552 some 30 years after the conquest of Tenochtitlan

(Mexico City) by Cortez, was returned to Mexico in 1990 by Pope John

Paul II from the Vatican library almost 440 years after it left

Mexico. The codex was the Latin version translated by Juan Badiano,

an Aztec nobleman, from the Nahuatl version (which did not survive)

written by Martin de la Cruz, an Aztec physician, both of whom were

members of the College of Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco (Byland, iii).

While

the literature I am discussing here is part of the indigenous

pre-Columbian literary legacy of Mexicans, it is also the indigenous

pre-Columbian literary legacy of Mexican Americans, the historical

baseline–its

roots, so to speak. Particularly since many of the symbols of the

Chicano Movement were appropriated from that indigenous past,

symbols like the Quinto Sol–as

in Quinto Sol Publications–and

Flor y Canto for literary and cultural gatherings. Quinto Sol

was the fifth sun under which the Nahuas believed they lived. Four

previous suns (worlds) had been des-troyed. In the pre-Columbian

indigenous society of Mexico literary and cultural festivities were

celebrated with flowers and songs–flor

y canto,

the name appropriated for Chicano literary events. What is

remarkable about the Chicano Movement is its iconography,

particularly its identification with the pre-Cortesian icons of

Mexico.

The

significance of the Chicano Movement and its off-spring the Chicano

Renaissance lies in how the Chicano Movement became instrumental in

the identity formation of Mexican Americans. Before the Chicano

Movement, Mexican Americans tended to regard them-selves via

perspectives Anglo America had of them–that

they were Coronado’s

Children. The Chicano Movement helped Mexican Americans in coming to

terms with the duality of their identity–that

they were not only Coronado’s

Children but also Montezuma’s

Children. To be whole–unless

they were purely indigenous–they

had to acknowledge the mestizaje (blending) that produced

them as la raza as they came to consider themselves

collectively. Chicano parents of the 60s readily gave their children

Nahuatl names.

The

first issue of El Grito: Journal of Mexican American Thought

published by Quinto Sol Publications in the Fall of 1967 proclaimed

editorially that Mexican Americans (becoming Chicanos) would say who

they were, not mainstream or Anglo America which saw them as “simple-minded

but lovable and colorful children who because of their rustic naïveté,

limited mentality, and inferior, backward ‘traditional

culture,’

choose poverty and isolation instead of assimilating into the

American mainstream and accepting its material riches and superior

culture.”

Inasmuch as the mainstream rhetoric about them was a “grand

hoax, a blatant lie–a

lie that must be stripped of its esoteric and sanctified verbal garb”–henceforth

they would reject that institutional and missionary main-stream

rhetoric about them and their heritage for a rhetoric that exalted

them as heirs of a heritage richer than the one being imposed on

them. “Only

Mexican Americans themselves”

could bring about “the

collapse”

of that “intellectually

spurious and vicious”

mainstream rhetorical structure about Mexican Americans by exposing

its “fallacious

nature”

via “the

development of intellectual alternatives.”

El

Grito

has been founded for just this purpose –to

provide a forum for Mexican-American self definition and expression

on this and other issues of relevance to Mexican-Americans in

American society today (Romano, 4).

Henceforth, Chicano readers would be judges of Chicano

literature which would create its own critical strictures and its

own critical aesthetic. El Grito was the manifesto of Chicano

liberation from Anglo-American intellectual traditions that

marginalized non-privileged perspectives. In a quantum leap, the

consequence of that editorial prompted Mexican Americans to look

back to their pre-Columbian indigenous roots while, at the same

time, helping them to take stock of their blended evolution.

Jose Vasconselos, the great Mexican educator, was right: los

mestizos had become la raza cosmica–the

cosmic people.

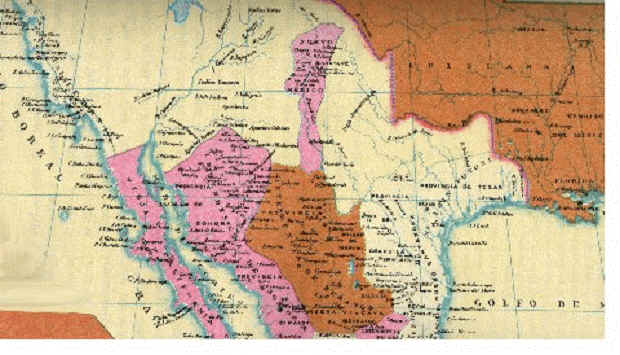

For Mexican Americans, what was missing was mythos–an

epic saga of la raza and its dias-pora in the United States.

Mexican Americans (now Chicanos) revivified the myth of Aztlan–the

ancient homeland of the Aztecs–as

an allegory for a Chicano homeland, an icon that has en-gendered

ideological wariness because of its putative designation for the

Aztec place of origin. The Hispanic Southwest–that

part of Mexico which was dismembered and annexed by the United

States per the Treaty

of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848 terminating the U.S. War

Against Mexico—would

become Aztlan.

No

one is sure where Aztlan was, except that in Aztec lore the

Aztecs emerged from the bowels of the earth through the seven caves

of Chicomostoc located in the heart of Aztlan. During

the fourth sun (Quarto Sol) of creation, a great tidal wave

destroyed Aztlan and forced the Aztecs to flee at the dawn of

the Fifth Sun (Quinto Sol). That flight resulted in the seven

peregrinations of the tribe, an odyssey that took them from the

original place of Aztlan across many lands over many

generations all the while keeping an eye out for the sign that

designated the place for their new homeland. Where they saw an eagle

perched on a cactus, holding in its beak a serpent, there would be

their new homeland. The city they built on the island surrounded by

Lake Texcoco in the valley of Anáhuac

they called Tenochtitlan after their designation as tenochcas.

Rendering

meaning from Aztec symbols is difficult because the Nahuatl language

provides for three levels of meaning for any given word--the

li-teral, the connotative, and the syncretic. Some scholars suggest

that by its very name, Aztlan must have been an island

homeland. Morphologically, Aztlan may have been originally Azatlan

(as inscribed in the current place word Mazatlan) with the

morphemes az, atl, and an. The morpheme a

generally designates water in the Nahua language, and the tl

is a noun marker. An is a place designation. Az has

been variously rendered as the word heron. Thus, Azatlan

could mean “the

watering place of the herons.”

Or “the

home of the herons mid the waters.”

And “Mazatlan”

means “watering

place of the deer.”

The fact that after their long trek the Aztecs found an eagle

perched on a cactus and holding a serpent in its beak on an island

in the middle of Lake Texcoco lends credence to the

suggestion that their original homeland could have been an

island surrounded by water—a

place where herons migrated to. The mor-pheme az may also be

rendered as eagle. The sign completes the mystery, particularly

since the eagle was the “national”

bird of the Aztecs.

A corollary bit of information raises an intriguing

suggestion. When we look at the word Atlantic we see the

morphemes atl, an and tic. Some scholars see a

linguistic correspondence between the word Atlantic and Azatlan

of the Aztecs. By extension, those scholars suggest that Aztlan

could be the Atlantis of fable mentioned in Plato’s

Cratylus. Far-fetched as that may sound, the linguistic

connection is not easily laid aside.

Much of what we know about the Aztecs, los Señores

de Mexico as they have come to be called, comes to us not from the

Aztecs themselves nor from primary sources but from sources

considerbly removed from the historical moments of the Aztecs. And

the primary sources that could have been of some use to us in

understanding the Aztecs were burned by the early prelates, like

bishop Zumárraga,

as pictographic representations of the devil. We do know that on the

eve of conquest, the population of the Aztec empire may have been as

high as 50 million (Borah and Cook, 4), twice the population of

present-day Iraq.

Added to this were the post-Cortesian accounts of the Aztecs

as barbarous and blood-thirsty cannibals. However, according to

Miller and Taube, for the Aztecs “the

eating of human flesh was neither common nor casual”

(54). Spanish efforts to denigrate further the Aztecs made them out

to be a derivative culture, always borrowing from other cultures to

enhance their own, much like the Romans appropriating Greek culture

to enhance their own. One such enhancement is reputed to have

occurred during the Aztec sojourn in the Toltec city of Tollan.

Be

that as it may, iconically Aztlan has be-come an important

symbol for Chicanos, for it has come to represent ideological

aspirations of the Chicano Movement. In terms of the latter, Aztlan

has been identified as the territory of the Mexican Cession through

which the Aztecs migrated in their diasporic search for their new

homeland. In the search for Aztlan some scholars place it in

central Oregon at a site some 10,000 years old. Others suggest that

the Aztecs could be the ancient Hohokam people of the Southwest four

corners area, particularly since the Hohokam played a game with hard

rubber balls similar to the game of the Aztecs. The Tanner-Disturnall

map so central to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo points to the

Casa-grande Ruins in Arizona as the “ruins

of the second houses of the Aztecs.”

And a site for Aztlan has been “marked”

on the coast of North Carolina, furthering the suggestion that the

Aztecs could have come from some Atlantic site, making ground on the

eastern shore of what is now the United States.

Surprisingly,

present-day Aztecs are not considered reliable informants about Aztlan.

There are still some 1.2 million Aztecs who live in south central

Mexico and who speak Nahuatl, though centuries removed from the

Nahuatl of the Aztec empire before Cortez. Ideologically, locating Aztlan

is of no import to the future of Chicanos. For Aztlan is a

country of the mind. That’s

how it began, much like the origins of Camelot, another country of

the mind. And perhaps that‘s

where it needs to stay.

As a country of the mind we are free to cogitate about Aztlan

however we may, to endow it with whatever characteristics we will.

It’s

not important how congruent our “sense”

of Aztlan is with the actualities of Aztlan, for no

one really knows what Aztlan may have been like save for the

remnant accounts we have in the surviving “literature”

of the Aztecs. For that matter, we know precious little about the

Aztecs except for the accounts passed on to us by the Spaniards. The

Aztecs received as bad a press from the Spaniards as Mexican

Americans have received from Anglos in the American South-west since

1848.

Until 1980 when I began researching the Aztecs for the play Madre

del Sol / Mother of the Sun commemorating the 450th

anniversary of the Virgin de Guadalupe (commissioned by

Arch-Bishop Patrick Flores of San Antonio), I had bought into the “history”

of the Aztecs as described in various texts–bloodthirsty

and serving up hundreds of human sacrifices daily. But my research

for Madre del Sol / Mother of the Sun turned up no pre-Cortesian

sources for the mal-characterization of the Aztecs. If the Aztecs

regularly sacrificed so many humans, I asked, where were the skulls?

When the Leakey’s

were excavating in the Olduvai Gorge they uncovered thousands of

skulls from antiquity. Surely such remains from Aztec times would

have been unearthed during excavation for the Mexico City subway.

Many other things turned up but no cache of skulls.

Anyway, Aztlan seems to have been an apt icon for the

Chicano Movement, particularly since the Chicano Movement sought to

elevate prominently the indigenous roots of Mexican American

identity, an identity that even in Mexico had become pervasive.

Chicanos were not seeking to eradicate their Spanish roots. Like the

dual creatures in The Dark Crystal, Chicanos sought to

reconcile the two parts of their identity--they were Indian and they

were Spanish.

By promoting pride in their Indian roots, Chicanos of the

Chicano Movement were building pride among Chicanos about who they

were. They were Mexico’s

children in the United States in a land once theirs; more

importantly they were Montezuma’s

Children–those

who had survived the Spanish holocaust. Their Aztec forebears

epitomized a great civilization in which medicine, mathematics,

philosophy, art, architecture, and engineering were taught; where

books were printed and writing was valued.

“Their

writing (and they had it in a full sense) was Ideographic”

(Gates, xxxviii).

Important to Chicanos in choosing Aztlan as an icon of

the Chicano Movement was that it heralded Chicanos as descendants of

an illustrious historical heritage. In this sense, Chicanos moved mejicano

identity beyond the Eurocentric. As a consequence of the Chicano

Movement and Aztlan, Chicanos gave notice to the American

mainstream that Chicano identity would be what Chicanos said it was

and not what the American mainstream said it was. Reaching across

the centuries to link up with Aztlan gave Chicanos a

historical center they did not have simply as an unanchored

diasporic people trying to come to terms with the infran-gibility of

their present and their past.

Aztlan

need not be real. Lots of people claim mythic homelands. The English

have Avalon and Camelot; the Germans have Valhalla;

the Tibetans have Shangri-la; the French have San Souci.

The strength of myth is the strength of pride that it engenders. Is

it important to know exactly where Aztlan was? What may be

more important is that for one brief and shining moment it was

and is still in the imagination of Chicanos where, like

Milton’s

unsightly root, in another country it bore a bright and golden

flower.

WORKS CITED

Borah,

Woodrow Wilson and Cook, Sherburne Friend. The Aboriginal Population of

Central Mexico on the Eve of the

Spanish Conquest, University of California Press,

1963.

Byland,

Bruce. “Introduction”

to An Aztec Herbal: The Classic Codex of 1552,

20000.

Diaz

del Castillo, Bernal. True History of the Conquest of New

Spain (A.P. Maudslay translation, 1958).

Foster, Nelson and Linda S. Cordell (Eds.), Chilies to Chocolate: Food the Americas Gave the World, University of Arizona Press, 1992.

Gates, William, “Introduction to the Mexican Botanical System,” An Aztec Herbal: The Classic Codex of 1552, 1939.

Leon-Portilla, Miguel. Pre-Columbian Literatures of Mexico, 1969.

Miller, Mary and Taube, Karl. An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya, 1993.

Ortego y Gasca, Felipe de. Backgrounds of Mexican American Literature, University of New Mexico, 1971.

Peterson, F. Ancient Mexico: An Introduction to the Pre-Hispanic

Cultures, 1959.

Romano, Octavio, ed. El Grito: Journal of Mexican American Thought, Volume 1, Number 1, 1967.

Steiner, Stan. La Raza: The Mexican Americans, 1969.

Copyright 2007 by the author. All rights reserved.

While

Edna Ferber was preparing for her great Texas novel, Giant, which

eventually was made into a movie, staring [Elizabeth Taylor, Rock

Hudson, and James Dean] she contacted my father Dr. Hector P. Garcia.

While

Edna Ferber was preparing for her great Texas novel, Giant, which

eventually was made into a movie, staring [Elizabeth Taylor, Rock

Hudson, and James Dean] she contacted my father Dr. Hector P. Garcia. Eduardo Peña received the 2009 National Hispanic Hero Award on

March 20, 2009 in Chicago, which included a video tribute. The award

was presented by the United States Hispanic Leadership Institute (USHLI)

during the organization's 27th annual conference, was attended by

over 6,000 past, present and future leaders representing 40 states.

Eduardo Peña received the 2009 National Hispanic Hero Award on

March 20, 2009 in Chicago, which included a video tribute. The award

was presented by the United States Hispanic Leadership Institute (USHLI)

during the organization's 27th annual conference, was attended by

over 6,000 past, present and future leaders representing 40 states.

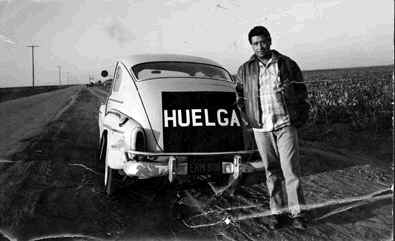

Benito,

who worked as a migrant farm worker as a young adult, was drawn to

Chavez for his heart and compassion but also because of his adamant

stand for improving working conditions.

Benito,

who worked as a migrant farm worker as a young adult, was drawn to

Chavez for his heart and compassion but also because of his adamant

stand for improving working conditions.

A group of Victoria teenagers rose above that and became successful,

known nationwide but never locally.

A group of Victoria teenagers rose above that and became successful,

known nationwide but never locally.

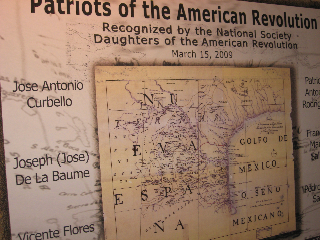

Judge Robert H.

Thonhoff, distinguish author and historian.

Author of, Texas Connection to the American Revolution. Both

Judge Butler and Judge Thonhoff have made significant contributions

to opening the doors for our Spanish Ancestors being recognize as

Patriots and descendants being eligible for membership into the

Daughters of the American Revolution and the Sons of the American

Revolution. Membership is encourage to join the National

Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, website address:

Judge Robert H.

Thonhoff, distinguish author and historian.

Author of, Texas Connection to the American Revolution. Both

Judge Butler and Judge Thonhoff have made significant contributions

to opening the doors for our Spanish Ancestors being recognize as

Patriots and descendants being eligible for membership into the

Daughters of the American Revolution and the Sons of the American

Revolution. Membership is encourage to join the National

Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, website address:

The SAR is

sponsoring a trip to Spain May 10 - 20, 2010, with an optional

3 day extension that will allow you to visit Gibraltar and Tangier,

Morocco. DAR, SR, Founders and Patriots, TCARA, Granaderos de Galvez,

Society of 1812 and other lineage and historical groups are invited to

participate. Robin and I will be leading the trip, supported by David

Eld, the travel agent who put together this trip as well as the SAR

1997 trip to Spain.

The SAR is

sponsoring a trip to Spain May 10 - 20, 2010, with an optional

3 day extension that will allow you to visit Gibraltar and Tangier,

Morocco. DAR, SR, Founders and Patriots, TCARA, Granaderos de Galvez,

Society of 1812 and other lineage and historical groups are invited to

participate. Robin and I will be leading the trip, supported by David

Eld, the travel agent who put together this trip as well as the SAR

1997 trip to Spain. Dr.

Hector's daughter, Daisy Wanda Garcia and I met by phone in 2006 and

had been communicating back and forth, ever since. I sent

her the wonderful news that we were primas, and we rejoiced that

beyond being the friends that we had become, we were actually

related!!

Dr.

Hector's daughter, Daisy Wanda Garcia and I met by phone in 2006 and

had been communicating back and forth, ever since. I sent

her the wonderful news that we were primas, and we rejoiced that

beyond being the friends that we had become, we were actually

related!!

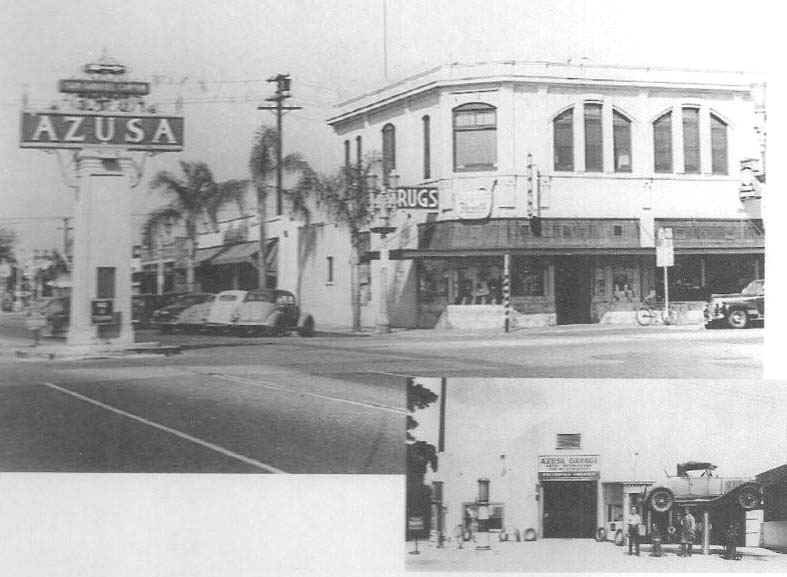

One

of the oldest pictures in their book, dates back to 1859, with many

family photos taken during the early 1900’s. The pictorial chapters

in this joint creation feature “Children from the Past”,

“Weddings”, “The Builders along Historic Route 66”, “School

Days”, which includes class pictures of elementary schools in Azusa

and Baldwin Park dating back to 1945. Other chapters included are also

“Los Soldados”, “Los Cabelleros”, and finally a chapter called

“Family and Friends.”

One

of the oldest pictures in their book, dates back to 1859, with many

family photos taken during the early 1900’s. The pictorial chapters

in this joint creation feature “Children from the Past”,

“Weddings”, “The Builders along Historic Route 66”, “School

Days”, which includes class pictures of elementary schools in Azusa

and Baldwin Park dating back to 1945. Other chapters included are also

“Los Soldados”, “Los Cabelleros”, and finally a chapter called

“Family and Friends.”

Skeletons

that may represent the remains of crew members from Columbus' second

excursion to the New World in 1493-94 were exhumed in 1990. The

burials were a part of La Isabela on the island of Hispaniola, now a

part of the Dominican Republic and that was the first European

settlement in the New World. Credit: Fernando Luna Calderon,

provided courtesy of T. Douglas Price

Skeletons

that may represent the remains of crew members from Columbus' second

excursion to the New World in 1493-94 were exhumed in 1990. The

burials were a part of La Isabela on the island of Hispaniola, now a

part of the Dominican Republic and that was the first European

settlement in the New World. Credit: Fernando Luna Calderon,

provided courtesy of T. Douglas Price

In

the picture are 10 stalwart young men, several of whom would gain fame

as first-rate archaeologists. Shown with them is Dr. Edgar L. Hewett,

head of training for the field school and the museum's newly appointed

director.

In

the picture are 10 stalwart young men, several of whom would gain fame

as first-rate archaeologists. Shown with them is Dr. Edgar L. Hewett,

head of training for the field school and the museum's newly appointed

director. Harry

Bingham's father's crowning achievement was his exploration of Machu

Picchu almost 100 years ago. Yet Hiram Bingham III's status as the

"discoverer" of the ruins is in dispute, and the Peruvian

government has demanded that Yale University, where Bingham taught,

return all the artifacts he took home from Inca lands.

Harry

Bingham's father's crowning achievement was his exploration of Machu

Picchu almost 100 years ago. Yet Hiram Bingham III's status as the

"discoverer" of the ruins is in dispute, and the Peruvian

government has demanded that Yale University, where Bingham taught,

return all the artifacts he took home from Inca lands.

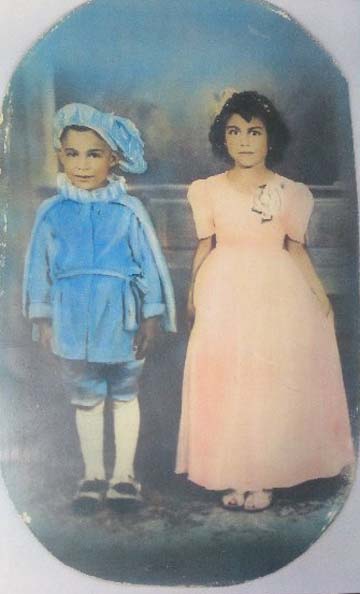

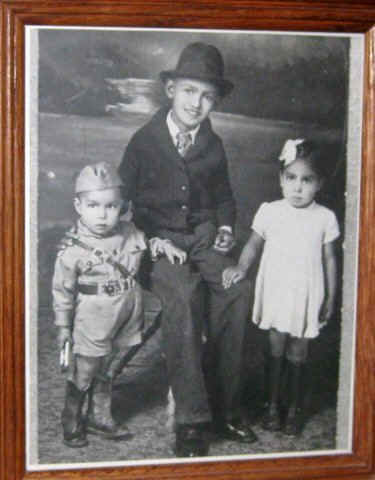

I

thought that you might use these pictures in your next issue of Somos

Primos in Texas history or Family genealogy. They were taken at the

San Fernando Mission in San Antonio Texas, circa 1940/41 at either a

Fiestas Patrias celebration or a Christmas pageant per my sister,

Maria, who is now in her mid-seventies. My sister was maybe 6/7 years

at the time. My brother was 4/5. My mother, Sapopa Rendon Hernandez,

hand sewed these outfits for both my brother Francisco, in the blue

page boy costume and Maria, in the pink princess costume. An

interesting point about this picture is that unknown to my mother, who

is now deceased, and to my siblings at that time, is that they were

wearing these outfits in a Mission that was built in the honor of King

Fernando 111, their grandfather, approximately 18 generations

removed!!

I

thought that you might use these pictures in your next issue of Somos

Primos in Texas history or Family genealogy. They were taken at the

San Fernando Mission in San Antonio Texas, circa 1940/41 at either a

Fiestas Patrias celebration or a Christmas pageant per my sister,

Maria, who is now in her mid-seventies. My sister was maybe 6/7 years

at the time. My brother was 4/5. My mother, Sapopa Rendon Hernandez,

hand sewed these outfits for both my brother Francisco, in the blue

page boy costume and Maria, in the pink princess costume. An

interesting point about this picture is that unknown to my mother, who

is now deceased, and to my siblings at that time, is that they were

wearing these outfits in a Mission that was built in the honor of King

Fernando 111, their grandfather, approximately 18 generations

removed!!

You are cordially

invited to a presentation by renowned Chicana artist Carmen Lomas

Garza

You are cordially

invited to a presentation by renowned Chicana artist Carmen Lomas

Garza

César

Chávez addresses an enthusiastic crowd, ca. 1966–1968.

Photograph by Jon Lewis. Courtesy of the

César

Chávez addresses an enthusiastic crowd, ca. 1966–1968.

Photograph by Jon Lewis. Courtesy of the

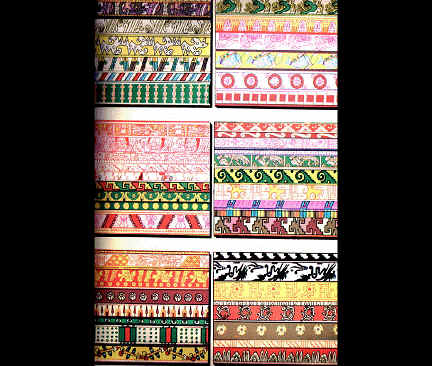

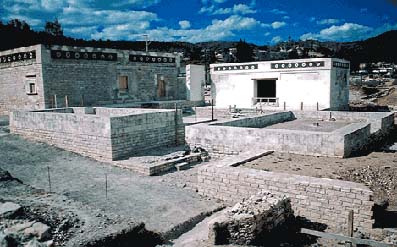

To

the west of the great Dominican priory of St. Peter and St. Paul

Teposcolula, in the Mixteca region of Oaxaca, stands the so-called

"Casa de la Cacica," a walled compound and palace, or tecpan,

built to house the local native nobility and serve as an

administrative center.

To

the west of the great Dominican priory of St. Peter and St. Paul

Teposcolula, in the Mixteca region of Oaxaca, stands the so-called

"Casa de la Cacica," a walled compound and palace, or tecpan,

built to house the local native nobility and serve as an

administrative center. Currently

in the final phase of restoration and reconstruction (above left: site

in 2009 ©Robert Jackson ) all the structures display plain but well

laid ashlar stonework. The main building, or "palace," is

the most elaborate, fitted with shaped stone openings and banded at

roof level by ornamental disk friezes, signifying an elite residence

in the Mexican tradition* .

Currently

in the final phase of restoration and reconstruction (above left: site

in 2009 ©Robert Jackson ) all the structures display plain but well

laid ashlar stonework. The main building, or "palace," is

the most elaborate, fitted with shaped stone openings and banded at

roof level by ornamental disk friezes, signifying an elite residence

in the Mexican tradition* . The

Friezes

The

Friezes

Protagonista. El escritor Carlos Fuentes durante las actividades

previas al Salón del Libro en París a celebrarse a partir de hoy y

hasta el próximo 18 de marzo.

Protagonista. El escritor Carlos Fuentes durante las actividades

previas al Salón del Libro en París a celebrarse a partir de hoy y

hasta el próximo 18 de marzo.