|

The

state of

California

is a very special place for many people. Millions have come here from

other parts of the

United States

and from around the world to live, work, and prosper. And many of these

people embrace their new lives in this western state.

As the world's fifth largest economy,

California

has a great deal to offer the many people who make their way to the

Golden

State

in search of a better life.

My

name is Jennifer Vo and to me and my family,

California

is a very special place. This

may be due to the fact that – my Chumash Indian ancestry

notwithstanding – I am an eleventh-generation Californian of Mexican

descent. In 1781 - when an

expedition was organized to bring a small group of civilian settlers

from Sonora, Mexico to take part in the founding of El Pueblo de

Nuestra la Reina de

Los Angeles

del Rio

Porcioncula - an escort of several dozen Mexican soldiers

serving under the flag of

Spain

were recruited. One of those soldier recruits who took part in

this important expedition was my

great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, Juan Matias

Olivas, an Indian from Rosario, Sinaloa.

From

my earliest memories, my family has always expressed its pride in its

California

roots. When my mother, Sarah Melendez Basulto Evans, was just a

teenager, she went to her grandfather's funeral in

Oxnard

,

California

. After the church service, the family had driven to the

Santa Clara

Cemetery

in

Oxnard

for the burial service.

Recounting

that day thirty-nine years ago, Mom told me, "Once the graveside

service had ended, my Uncle Simon [Melendez] took me for a long walk,

pointing out the various tombstones for many of our ancestors. I

was amazed that he could recount so many stories and names from our

family history. As we walked along, Uncle Simon explained to me

that our family had been in

California

for a very, very long time. For him, this was a great source of

pride. I remember his words very clearly when he said, 'Our family

has known no home but

California

. This is where we belong.' From that day forward, I have

always felt a great emotional attachment to

California

, the land of my ancestors."

Sarah

also told me that Uncle Simon had explained to her that our

California

family has had a long and proud tradition of military service extending

back to our earliest

California

ancestor. One generation after another had joined the military to

defend the only land that we could call home. And,

although Mexican Americans in

California

have been treated unfairly at times, our resolve to defend this state

and this country has never wavered.

As

I was growing up, my mother expressed these sentiments to me, and for

this reason, I have always told people that I am proud to be a

descendant of the

California

pioneers. And, over time, I have gradually learned the details

about my family's military service. From the first moment Juan

Matias Olivas entered

California

- and for the better part of nine generations - my family has played a

role in the defense of

California

. And, in some cases, members of my family had to make the ultimate

sacrifice to safeguard the security of

California

. Over a period of two centuries, the flags, the causes, and the

surnames have changed, but my family's legacy of military service to

California

has endured.

First

Generation:

Juan

Matias Olivas

was born two and a half centuries ago near

Rosario

in what is today known as the state of Sinaloa (in the

Republic

of

Mexico

). On May 25, 1777, Juan was married at Nuestra Señora del

Rosario Church in

Rosario

to María Dorotea Espinosa. Three years later, their second child,

José Pablo Olivas, came into the world and was baptized in the same

church.

On

August 6, 1780, Juan Matias Olivas, enlisted for ten years as a soldado

de cuera (leather-jacket soldier), attached to the Military

District of Monterrey of northern

Mexico

. Interestingly, Juan Matias' discharge papers of 1798

provide us with his physical description. He was 5 feet and 2

inches in height and had black hair and black eyes. In addition,

Juan Matias had olive skin and - unlike many of his fellow soldiers -

was clean-shaven, an obvious manifestation of his predominant Native

American ancestry.

Joining

Spain

's frontier army offered Juan and his family with great opportunities

that were not available to Indians who lived in the

Rosario

area. If he had stayed in

Rosario

, Juan Matias Olivas would have been destined to a life as a poor and

lowly Indian laborer, subject to the whims of his hacienda jefe and to a

society that classified him within the lower rungs of a racist caste

system.

But,

as a soldier serving in the Spanish military, Juan Matias would be

permitted to ride a horse, carry his own weapon, have access to skilled

medical attention, and enjoy free housing. Such a profession also

provided him with retirement benefits and guaranteed that his wife would

receive a pension if he died while performing his duties.

At

about this time, Captain Fernando Rivera was scouring the coastal cities

of Sinaloa and

Sonora

to find and recruit 59 soldiers and 24 families of pobladores (settlers)

who would make up the nucleus of an important expedition to the north.

The ultimate goal of the expedition would be the founding of the Pueblo

of Los Angeles and the Military Presidio of Santa Barbara. In the

end, Rivera was only able to recruit twelve families, which would be

accompanied by 59 soldiers on the northward journey.

Late

in the winter of 1781, the expedition embarked. The soldier Juan

Matias, his wife -María Dorothea Espinosa, then 23 years old - and

their two young children, María Nicolasa and José Pablo - took part in

the 960-mile journey, arriving at the San Gabriel Mission on August 18,

1781. In the months following their arrival at the

Mission

, Juan Matias Olivas and his family were housed with the rest of the

soldier families near the mission. Soon after, on the

morning of September 4, 1781, the Pueblo of Los Angeles was founded,

with forty-four settlers and several soldiers in attendance. It is

likely that the services of several soldiers - including Juan Matias

Olivas - were needed to help the small pueblo get started. Juan

Matias, as a matter of fact, would - after his enlistment ended - make

his retirement home in the small pueblo.

Early

in the next year, Juan Matias Olivas and forty-one other soldiers made

their way to the Santa Barbara Channel, where, on April 21, 1782, the

Santa Barbara Presidio was founded. Not long after, the

families followed and the rest of my ancestor's military career would be

spent at the Santa Barbara Presidio.

As

a Presidio soldier, Juan Matias Olivas and the other soldiers had a

multitude of responsibilities: Sometimes they delivered the mail

to other parts of

California

or escorted priests to and from their destinations. A regular

escort of fifteen soldiers from

Santa Barbara

were posted to guard the San Buenaventura Mission. And, of course, there

was always the possibility that they would be called upon to take part

in an Indian campaign. (The soldados posted in

New Mexico

,

Arizona

,

Texas

and

Chihuahua

were almost constantly at war with the indigenous groups. By

comparison,

California

was relatively calm and the Spaniards cultivated their relationships

with most of the Indian groups surrounding their presidios.)

After

a few years at the Presidio, Dorotea died, leaving poor Juan Matias a

widower with six children, including Pablo. Not long after he was

widowed, Juan Matias Olivas was tallied in the 1790 census of the Real

Presidio de

Santa Barbara

. Listed as a 31-year-old widower, Juan Matias was classified was an

Indian and a native of

Rosario

. Four of his six children were listed as living with Juan Matias.

By now, the entire population of the Santa Barbara Presidio had reached

230 individuals, comprising 24 percent of the entire Hispanic population

of

Alta California

.

In

March 1794,

Spain

declared war against

France

. Eventually the news of this war arrived in

California

. The soldiers became acutely aware of the fact that both

France

and

England

yearned for the opportunity to take

California

into their own empires. But it was not likely that the two hundred

and seventy-five soldiers at the four presidios in

California

could have held off a serious invasion by a foreign power.

Nevertheless, the presidio was their home and steps were taken to

safeguard the safety of their families and possessions in case of

attack.

On

June 1, 1794, Juan Matias married his second wife, Juana de Dios

Ontiveros, at the San Gabriel Mission. After their marriage,

Matias and Juana had several children. Then, on November 23, 1798,

Juan Matias Olivas, now 40 years of age, was discharged from the

military after eighteen years of service. Two years later, Juan

Matias Olivas and his family took up residence in the small pueblo of

Los Angeles

. By this time, the small pueblo had seventy families, 315 people,

and consisted of thirty small adobe houses. He died a

few years later.

Second

Generation:

My

great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather, José Pablo

Olivas, the son of Juan Matias and Dorotea, had been born in

Rosario, Sinaloa, on January 25, 1780 as the legitimate son of Juan

Matias Olivas and Dorothea Espinosa. But, from the age of two,

Pablo grew up within the walls of the Santa Barbara Presidio.

Living at close quarters with fifty other families was no easy chore,

but the inhabitants of the garrison were united in their camaraderie as

the families of soldiers. As a child, José Pablo attended the

same church services as his future wife, María Luciana Fernández, the

first-born child of another presidial soldier, José Rosalino Fernández.

Around

the turn of the century, José Pablo Olivas stepped into his father's

footsteps and became a soldier of the presidio. In a roster of

individuals dated February 17, 1804, Pablo Olivas was listed as one of

the fifty-four soldiers on active duty at the Santa Barbara Presidio.

Four years earlier, he had married María Luciana Fernández.

Between 1801 and 1812, José Pablo and María Luciana would have eight

children, including my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, José

Dolores de Jesus Olivas, who was baptized on Nov. 3, 1802 at

Santa Barbara

, and would represent the third generation of soldiers in my family.

Mexico

's

struggle for independence against

Spain

began on the night of September 15/16, 1810 when a mild-mannered Creole

priest, Father Miguel de Hidalgo y Castillo, published his famous outcry

against tyranny from his parish in the

village

of

Dolores

. His impassioned speech - referred to as Grito de Hidalgo ("Cry of

Hidalgo") - set into motion a process that would not end until

August 24, 1821 with the signing of the Treaty of Córdova.

From

1810 through 1821,

Mexico

's war of liberation interfered with the arrival of Spanish supply ships

in

California

. Eventually, supplies dwindled to a mere trickle, making the

California

presidios more dependent upon the local missions for food supplies and

manufactured items. By 1813, the Commandant of Santa Barbara

informed the Governor that his soldiers were without shirts and had

little food; in addition, the presidio soldiers received no pay for

three years, and pensions were suspended. Four years later, on

December 16, 1817, José Pablo Olivas, the second-generation soldier,

died.

Third

Generation:

José

Pablo died when his son José Dolores Olivas was only

fifteen years of age. It was during this period of intense

upheaval that José Dolores Olivas stepped into his father's shoes and

served as a third-generation soldado de cuera. José Dolores

Olivas was actually the first of my Olivas ancestors to be born in

California

, and he would become the third generation of Olivas men to become a

soldado de cuera at the Santa Barbara Presidio. It was his destiny

to see the transition of

California

as it passed from the hands of the Spanish empire to the newly

independent Mexican state. And he would serve as a soldier to both

nations.

In

1821,

Mexico

had finally achieved independence from

Spain

, and on April 1822, the

California

soldiers were notified the revolt had been successful. Almost

immediately, the

California

presidios lowered the Spanish flag and

California

became a province of the new nation. On April 13, 1822, José

Dolores Olivas and the other soldiers at the Santa Barbara Presidio took

their oath of allegiance to the new government in

Mexico City

.

On

June 14, 1829, José Dolores de Jesus Olivas was married to María

Gertrudis Valenzuela at Mission Santa Ynez. Dolores Olivas was

listed as a single soldado de cuera and a native of the

Santa Barbara

. His bride, Gertrudis, was a daughter of another presidio

soldier, Antonio Maria Valenzuela and his wife, María

Antonia Feliz. María Gertrudis Valenzuela had been baptized

sixteen years earlier on June 7, 1813 at the San Gabriel Mission.

Like her husband, she was the daughter of a presidial soldier and had

spent most of her early years growing up at the presidio.

As

José Dolores and Gertrudis prepared to start their family in 1830, they

took their position as members of the growing

Santa Barbara

presidial community, which now numbered 604. Between 1830 and 1850, José

Dolores and Gertrudis became the parents of twelve children. My

great-great-great-great-grandmother, María Antonia Olivas, born in

February 1834, was the fourth-born child of this group, although she

shared that position with her twin sister.

After

serving out his term of enlistment, Dolores Olivas retired from the

military and became an agricultural laborer. He and his family

continued to live in the vicinity of the presidio. It was during

this time that President James K. Polk of the

United States

devised a strategy for snatching

California

from the hands of the

Mexican

Republic

.

In

the fall of 1845, President Polk sent his representative John Slidell to

Mexico

.

Slidell

was supposed to offer

Mexico

$25,000,000 to accept the

Rio Grande

boundary with

Texas

and to sell

New Mexico

,

Arizona

, and

California

to the

U.S.

However, the President of Mexico turned this down, and in May

1846 Polk led his country into war.

The

Mexican-American War in

California

ended on January 13, 1847 with the signing of the Treaty of Cahuenga.

A year later, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2,

1848, ending all hostilities between the two nations. By the

provisions of this treaty,

Mexico

handed over to the

United States

525,000 square miles of land, almost half of her national territory.

In compensation, the

U.S.

paid $15,000,000 for the land and met other financial obligations to

Mexico

. By the provisions of this peace treaty, the Mexican citizens

living in

California

were offered American citizenship and full protection of the law.

The

area which

Mexico

transferred to American control in 1848 contained a population of 82,500

Mexican citizens, 7,500 of which lived in

California

. Two years later, on September 9, 1850,

California

was admitted to the

Union

as the thirty-first state. During the Federal Census of the same

year, my ancestor, José Dolores Olivas - now an American citizen - was

tallied in his

Santa Barbara

residence as the head of a household of eleven. My ancestor would

die a few years later.

Fourth

Generation:

At

the time of the 1850 census, my great-great-great-great-grandmother, María

Antonia Olivas, was only 15 years of age. María Antonia

Olivas was truly a daughter of the Californian military establishment.

She was descended from five pioneer

California

families (Olivas, Fernández, Valenzuela, Feliz and Quintero) and lived

at the Santa Barbara Presidio which four of her soldado ancestors had

helped to found. Her father (José Dolores Olivas)

was a retired soldier. Both of her grandfathers were

California

soldiers (José Pablo Olivas and Antonio María Valenzuela),

as were all four of her great-grandfathers (Juan Matias Olivas,

José Rosalino Fernandez, Pedro Gabriel Valenzuela, and Anastacio María

Feliz).

On

November 30, 1849, María Antonia Olivas was married to José Apolinario

Esquivel, a native of

Irapuato

,

Guanajuato

,

Mexico

, at the Santa Barbara Mission. The two of them relocated to the

San Buenaventura Township to raise their family and tend their crops.

Her brother, José Victoriano Olivas, four years younger

than she was, would become the fourth generation Olivas to serve as a

soldier in the defense of

California

.

The

American Civil War (1861-1865) divided the American people into two

camps and resulted in more casualties than any other war in American

history. Many of the hostilities in this war took place in the

eastern half of

North America

, especially in the Southern states. For the most part,

California

- which was a Union state - seemed removed from most of the battlefields

and action that was taking place.

In

1863, as the Civil War raged in the eastern and southern states, the

United States Government became concerned about possible Confederate

incursions into

New Mexico

and other Union-held areas. In order to avoid such confrontations,

the U.S. Government authorized the military governor of

California

to organize four military companies of Mexican-American Californians

into a cavalry battalion in order to utilize their "extraordinary

horsemanship."

Major

Salvador Vallejo was selected to command this new

California

militia, with its five hundred soldiers of Spanish and Mexican descent.

Company C of the First California Native Cavalry was organized under

Captain Antonio María de la Guerra. María Antonia’s brother

José Victoriano Olivas joined this company, which was made up of native

troopers from

Santa Barbara

County

. This battalion primarily served in

California

and

Arizona

, guarding supply trains, and helped defeat a Confederate invasion of

New Mexico

. José Victoriano Olivas would thus become the fourth generation

of the Olivas family to serve in the military. And this service

had now been extended to three flags (

Spain

,

Mexico

, and the

United States

).

Fifth

Generation:

My

ancestor Regina Esquivel was born in 1851 as the daughter

of José Apolinario Esquivel and María Antonia Olivas and as an

American citizen. Nineteen years later, on January 3, 1870, Regina

Esquivel was united in marriage with Gregorio Ortega at the San

Buenaventura Mission. Gregorio was a laborer who had emigrated from

southern

Mexico

in the 1860s. Over the next two decades, Gregorio and

Regina

would become the parents of eighteen children.

Sixth

Generation:

On

September 16, 1875, Gregorio Ortega and Regina Esquivel became the

parents of Valentine Ortega. Eighteen years later,

Valentine was united in marriage with one 18-year-old Theodora Tapia, a

native of the

Los Angeles

area. Valentine and Theodora had five children in all, including

Isabel (born in 1902), Paz (born in 1906) and Luciano P. Ortega (born in

1908).

During

the early Twentieth Century, this family lived in the Saticoy District

of Ventura County,

California

. Saticoy was nine miles east of the county seat, the City

of

Ventura

. In 1918, at the age of forty-three years, my

great-great-grandfather Valentine Ortega fell victim to the worldwide

influenza epidemic that ravaged the American continent at the end of

World War I.

Seventh

Generation:

As

Isabel Ortega and her siblings grew up, they witnessed

what would eventually be called the First World War. Initially the

war broke out in Europe and, it was not until three years later that

America

would join this conflict, with its declaration of war on

Germany

on April 6, 1917. During this war, the American military was rife

with discrimination against Hispanic and African-American soldiers.

Soldiers with Spanish surnames or Spanish accents were sometimes the

object of ridicule and relegated to menial jobs, while African Americans

were segregated into separate units. Some Hispanic Americans who

lacked English skills were sent to special training centers to improve

their language proficiency so that they could be integrated into the

mainstream army.

My

great-grandmother, Isabel Ortega, married Refugio Melendez, an immigrant

laborer from Penjamo, Guanajuato. Refugio and Isabel met during

the 1920s and their first-born child was my grandmother, Theodora (Dora)

Melendez, who was born in November 1927. Dora was followed two

years later by my Uncle Raymundo Melendez. Isabel and Refugio

raised their family in Saticoy, living right across the street from the

Ortega family during the 1930s and 1940s.

The

Great Depression was a difficult time for my family as it was for most

American families. But the beginning of World War II was an

ominous event for all Americans. For three years, the

United States

avoided this war, which pitted the Axis Powers (

Germany

,

Italy

and

Japan

) against a multitude of other nations, including

Great Britain

, the Soviet Union, and

China

.

On

December 7, 1941, everything changed. The surprise attack on the

American naval fleet at Pearl Harbor in

Hawaii

would bring

America

into this struggle against tyranny. And when Uncle Sam called for

recruits, his call was answered. By the end of the war in

September 1945, sixteen million men and women had worn the uniform of

America

's armed forces.

At

the time of

America

's entry into World War II (1941), approximately 2,690,000 Americans of

Mexican ancestry lived in the

United States

. Eighty-five percent of this population lived in the five

southwestern states (

California

,

Arizona

,

New Mexico

,

Texas

, and

Colorado

). Like other ethnic groups, Mexican Americans responded in great

number to our nation's dilemma. At least 350,000 Chicanos served

in the armed services and seventeen Hispanic individuals won the

Congressional Medal of Honor.

California

played an important role in World War II. Eighteen California

National Guard Divisions were sent overseas, and thousands of men

enlisted or were drafted. According to the United States War

Department, California - containing 5.15% of the population of the

United States

- contributed 5.53% of the total number who entered the Army. Of

these men and women from

California

who went to war, 3.09% failed to return home, representing 5.54% of the

American casualties

In

1942, my great-uncle Luciano P. Ortega - the brother of my

great-grandmother Isabel - was drafted into the armed forces. For

some reason, his name was Americanized to Joseph P. Ortega while he was

in the service, but our family has always called him Luciano.

Luciano was attached to the 34th Infantry Regiment of the 24th Infantry

Division, which was on the front lines in the war against

Japan

.

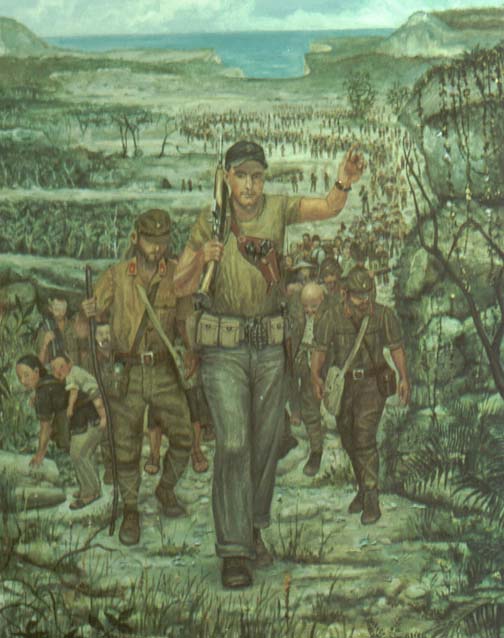

During

October and November 1944, the 24th Infantry Division was involved in

the campaign to eject the Japanese from

Leyte

in the Philippine Islands. Then, on November 19, 1944, Uncle

Luciano was killed in action. He was buried in the

Manila

American

Cemetery

in the capital city. My uncle by marriage, Joseph Torres (the

husband of Lucy Ortega) - who also served in the

Philippines

- saw Uncle Luciano's grave and informed the family of where the body

had been laid to rest. However, my great-great-grandmother,

Theodora Tapia Ortega, never reconciled herself to her son's death and

refused to accept it. Instead, she continued to believe that he

was missing in action and would someday return home to Saticoy.

Eighth

Generation:

The

eighth generation of my family was involved in two wars: World War

II and the Korean War. Late in World War II, Chello O.

Ortega, the son of Paz Ortega (a sister of Luciano and Isabel

Ortega) and Laurencio Ortega, went to war. He was the second

Ortega to go to the Army from Saticoy and - like his uncle Luciano

- was sent to the Pacific Theater. On May 8, 1945, Nazi Germany

had surrendered unconditionally to Allied forces. However, the war

in the Pacific Theater continued unabated.

On

June 27, 1945, a month-and-a-half after Nazi Germany had surrendered,

the Oxnard Press Courier announced that Chello Ortega from

Saticoy was missing in action in the Pacific Theater. Nine days

later, on July 6, 1945, the same newspaper announced the sad news that

Chello Ortega had been killed in action (although his exact date of

death is not known to us). Less than two months later, Japan would

surrender and peace would finally come to

America

after three years and nine months of war.

As

World War II drew to an end, the three Melendez brothers - sons of

Refugio Melendez and Isabel Ortega and brothers to my grandmother Dora -

were teenagers. Raymond (Raymundo) Ortega Melendez

had been born in 1929 and yearned to join the military. In 1945,

at the age of 17 - with his parents' permission - Ray entered the

American armed forces. This would mark the beginning of a long

military career, which would take him through the Korean and Vietnam

Wars before his retirement in 1969.

The

Korean War began in 1950, only five years after the end of World War II.

The participation of Mexican Americans and other Hispanics in the Korean

War was such that the Department of Defense publication, Hispanics

in America's Defense (Collingdale, Pennsylvania: Diane

Publishing Co., 1997), has paid tribute to their contribution:

"The Korean Conflict saw many Hispanic Americans responding to the

call of duty. They served with distinction in all of the

services…. Many Mexican Americans from barrios in

Los Angeles

,

San Antonio

,

Laredo

,

Phoenix

, and

Chicago

saw fierce action in

Korea

. Fighting in almost every combat unit in

Korea

, they distinguished themselves through courage and bravery as they had

in previous wars."

By

the end of the Korean War, all three of my grandmother's brothers,

Raymond, Donald (Danny) and Simon would join the United States Army.

During this war, Uncle Ray served as an airborne paratrooper for many

years. But my Uncle Simon Melendez's experiences in the Korean War

are the stuff that legends are made of.

Born

on October 28, 1930, Simon Ortega Melendez was raised in

Saticoy and attended

Ventura

Junior High School

and

Ventura

City

College

. When the Korean War started, Simon joined the 2nd Division of

the U.S. Army and became a machine gunner. It would be Uncle

Simon's destiny to take part in two of the bloodiest battles of the

Korean War. The "Battle of Bloody Ridge" began in August

1951 and continued up until September 12, 1951. On August

27, Simon was hit in the neck and legs by mortar shrapnel and in the

back by grenade fragments. At the same time, he was separated from

his platoon. For seven days, he was behind enemy lines and

disoriented by torrential rains that made his weapon inoperable.

The

rain did not stop until the sixth day, and on the seventh day he was

able to make his way into the area of the 9th U.S. Regiment. When

asked how he managed to make his way through enemy lines for seven days,

21-year-old Simon explained that "my extreme faith in God brought

me through." Soon after this, Uncle Simon was able to have a

three-day reunion with his brother Ray near the front lines.

Raymond, who had already been in the service for six years, was a

paratrooper and had been stationed about a 100 miles from Simon's

position. Soon after, Simon was once again in the thick of the

fighting when his unit took part in the "Battle of Heartbreak

Ridge," which lasted from September 13 to October 22, 1951.

The

Battles of Bloody Ridge and Heartbreak Ridge were the two bloodiest

battles of the Korean War. By the time he left the service, Simon

had been awarded the Silver Star, the Bronze Star, and three Purple

Hearts. He also founded the Mexican-American Korean War Veterans

of Ventura County and became a life member of the Veterans of Foreign

Wars and the American Legion. Simon Melendez, the proud Korean War

veteran, died at the age of 71 on June 15, 2002, surrounded by a family

that adored him. Even to this day, Uncle Simon's memory remains

strong with me and my family, in large part because he had a larger than

life personality that endeared him to everyone.

Donald

Ortega Melendez,

who was born in 1936, entered the service in 1954 at the tail end of the

Korean War. Like his brother Raymond, he initially joined the

paratroopers. During his first stint overseas, Donald was assigned

to the 9th Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Infantry division. He did

three separate hitches overseas and was on service during the Cuban

Missile Crisis of 1962. Uncle Donald spent 25 years in the

military and achieved the rank of First Sergeant before he retired in

1979.

Uncle

Ray, also an airborne paratrooper, served all around the world at one

time or another and achieved the rank of Command Sergeant Major by the

time he retired in 1969. Like Donald, Uncle Ray was a career

military person and does not feel that he is at liberty to discuss his

military service in great detail. Uncle Simon - after his Korean

War service - had been offered a promotion too, but he decided that he

was ready for civilian life.

Ninth

Generation:

Four

members of our family's eighth generation served in the military,

possibly even more that I do not know about. But the military

tradition has carried through to the present generations and the number

of Ninth Generation family members who have served in the military is

hard to tally. Luciano Ortega's daughter, Geraldine, joined the

military for a long period of time. Donald's son Daniel Melendez

followed in his father's step and served as a paratrooper from 1970 to

1982. Uncle Simon had two sons who spent a number of years in the

military: Ricardo Melendez served in the air force and

Roy

enlisted in the U.S. Marines.

When

he was twenty years old, my mother's brother, Eusebio Javier

Melendez Basulto followed in our family's military tradition by

enlisting in the U.S. Army. He served in Military Intelligence

with MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) Unit 406 ASA, where he

achieved the rank of Specialist, Fourth Class. Uncle Eusebio's

military career lasted from 1973 to 1985, a total of 12 years, after

which he became a chemist in the civilian world.

During

the extended Vietnam Conflict (1963-1973), approximately 80,000 Hispanic

Americans served in the American military. Although Hispanics made up

only about 4.5% of the total

U.S.

population at that time, they incurred more than 19% of the casualties.

In all, thirteen Hispanic soldiers received the Medal of Honor during

this conflict.

Continuing

this trend of service into the last decade of the Twentieth Century,

twenty thousand Hispanic servicemen and women participated in Operation

Desert Shield and Desert Storm (1990-1991). Writing in Hispanic Heritage

Month 1996: Hispanics - Challenging the Future, Army Chaplain (Captain)

Carlos C. Huerta of the First Battalion, 79th Field Artillery stated

that "Hispanics have always met the challenge of serving the nation

with great fervor. In every war, in every battle, on every battlefield,

Hispanics have put their lives on the line to protect freedom."

As

Mexican-American citizens of

California

, my family has carried on a proud tradition of military service.

When our nation has been in need, my ancestors - from the earliest days

in

California

- answered the call with a sense of pride and obligation. This

sense of duty is a deeply held tradition to all Mexican-Americans.

Although

I have inherited my dark eyes and thick dark hair from my Mexican

ancestors, I am also German and Anglo-American through my father's side

of the family. For this reason, it is not readily evident to some

people that I am Mexican-American. As a result, I have - on

occasion - heard friends and acquaintances express less than flattering

opinions about Mexican immigrants or Mexican Americans.

Such

comments and criticisms - although they were undoubtedly based on

ignorance or fear - hurt me and were an affront to my family's pride and

dignity. I can only say - in response to such hurtful comments -

that I hope those people are reading this article. If I could

speak to them today, I would tell them that my family - for two

centuries - has been fighting for their freedom. And when my Uncle

Luciano Ortega and my Cousin Chello Ortega were killed in action during

World War II, they were sacrificing their lives for the freedom of all

Californians.

DEDICATION:

This work is dedicated to my ancestors who have defended

California

for two centuries:

1.

José Matias Olivas - Soldier in the Service of

Spain

, 1781-1798

2.

José Pablo Olivas - Soldier in the Service of

Spain

, 1804-1817

3.

José Dolores Olivas - Soldier in the Service of

Spain

and

Mexico

4.

José Victoriano Olivas - Civil War Veteran (1863-1865)

5.

Joseph Luciano Ortega - World War II -

Killed

in action, Philippine

Islands

, November 19, 1944

6.

Chello Ortega - World War II -

Killed

in action, Pacific Theater, June 1945

7.

Raymond Ortega Melendez, Korean War Veteran and Career Soldier

(1945-1969)

8.

Donald Ortega Melendez, Korean War Veteran and Career Soldier

(1954-1979)

9.

Simon Ortega Melendez, Korean War Veteran

10.

Eusebio Basulto, Jr., Specialist, Fourth Class in Military Intelligence

(1973-1985).

Special

Acknowledgments: We thank Eva Melendez Aubert, Dora Melendez

Basulto, Eusebio Basulto, Donald Ortega Melendez, Sarah Basulto Evans,

and the Simon Ortega Melendez family for their valuable contributions to

this tribute.

Copyright

© 2009, by Jennifer Vo and John P. Schmal.

All rights under applicable law are hereby reserved.

Sources:

Interviews

conducted by Jennifer Vo, Sarah Basulto Evans, and John Schmal.

Spanish

and Mexican military research conducted by Robert Lopez and John Schmal.

California

Archives,

Provincial

State

Papers, 1767-1822 (Archives of

California

, Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley).

Office

of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Manpower and

Personnel

Policy

,

U.S.

Department of Defense. Hispanics in

America

's Defense (Collingdale, Pennsylvania: Diane Publishing Co.,

1997).

Robert

S. Whitehead, Citadel on the Channel: The Royal Presidio of

Santa Barbara

: Its Founding and Construction, 1782-1798 (Santa Barbara:

Santa Barbara Trust for Historical Preservation, 1996).

War

Department. The Adjutant Generals Office. Administrative Services

Division. Strength Accounting Branch. World War II Honor List of

Dead and Missing Army and Army Air Forces Personnel from California,

1946 - from Record Group 407: Records of the Adjutant General's

Office, 1917- [AGO], 1905 - 1981

American

Battle Monuments Commission. “National World War II Memorial”

Online: http://www.wwiimemorial.com/

2003.

Jennifer

Vo and John P. Schmal, A Mexican-American Family of

California

: In the Service of Three Flags (Heritage Books, 2004).

|

Judges said the exhibit was chosen for the national award — the

top winner in the Diversity Programs category — because it was the

first time Latino alumni had been honored in such a way and because

the exhibit helps to educate the public while embracing a culture that

may be the majority in California by 2017.

Judges said the exhibit was chosen for the national award — the

top winner in the Diversity Programs category — because it was the

first time Latino alumni had been honored in such a way and because

the exhibit helps to educate the public while embracing a culture that

may be the majority in California by 2017.

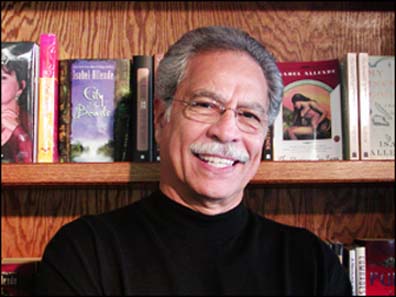

Martinez, the recipient of a MacArthur

Foundation Fellowship (familiarly referred to as a "genius

grant") in 2004, is the owner of Santa Ana's Libreria Martinez Books

and Art Gallery. He's also been a speaker at hundreds of events at

schools, nonprofits and conferences throughout the world, and is known as

a champion of literacy, especially in the Latino community.

Martinez, the recipient of a MacArthur

Foundation Fellowship (familiarly referred to as a "genius

grant") in 2004, is the owner of Santa Ana's Libreria Martinez Books

and Art Gallery. He's also been a speaker at hundreds of events at

schools, nonprofits and conferences throughout the world, and is known as

a champion of literacy, especially in the Latino community.

Latino

teens who actively embrace their native culture and whose

parents become more involved in U.S. culture develop healthier

behaviors, U.S. researchers say.

Latino

teens who actively embrace their native culture and whose

parents become more involved in U.S. culture develop healthier

behaviors, U.S. researchers say.  An

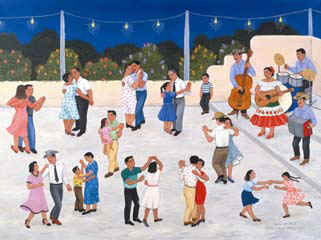

interactive exhibit inspired by the works of nationally acclaimed

artist Carmen Lomas Garza. How does your family celebrate special

occasions? What are your family's daily routines? Every child

inherits his or her own cultural identity through the everyday

routines and

An

interactive exhibit inspired by the works of nationally acclaimed

artist Carmen Lomas Garza. How does your family celebrate special

occasions? What are your family's daily routines? Every child

inherits his or her own cultural identity through the everyday

routines and  special

traditions of family life. Step into Carmen's world and explore

Mexican-American culture.

special

traditions of family life. Step into Carmen's world and explore

Mexican-American culture.

Major

General LaRita A. Aragon is the Air National Guard assistant to the

deputy chief of staff of Staff Manpower and Personnel. She serves as

the senior Air National Guard officer responsible for comprehensive

plans and policies covering all life cycles of military and civilian

personnel management, which includes military and civilian end

strength management, education and training, and compensation and

resource allocation. General Aragon serves on the Air Force Personnel

Board of Directors for personnel integration matters.

Major

General LaRita A. Aragon is the Air National Guard assistant to the

deputy chief of staff of Staff Manpower and Personnel. She serves as

the senior Air National Guard officer responsible for comprehensive

plans and policies covering all life cycles of military and civilian

personnel management, which includes military and civilian end

strength management, education and training, and compensation and

resource allocation. General Aragon serves on the Air Force Personnel

Board of Directors for personnel integration matters.

I

I

Saturday,

July 18th ~ Main Street in historic Downtown

Santa Paula

Saturday,

July 18th ~ Main Street in historic Downtown

Santa Paula

voices!

In a close vote, the committee voted 6 to 4 to

eliminate General Fund support to the state parks,

replacing it with a State Parks Access Pass, funded by

a $15 surcharge on vehicle license fees. The

State Parks Access Pass, originally proposed last year

by our own then-Assemblymember John Laird, is a

long-term solution that would keep our parks open.

However, there's a very long way to go before a final

budget is adopted and anything can happen in the

twists and turns of budget negotiations.

voices!

In a close vote, the committee voted 6 to 4 to

eliminate General Fund support to the state parks,

replacing it with a State Parks Access Pass, funded by

a $15 surcharge on vehicle license fees. The

State Parks Access Pass, originally proposed last year

by our own then-Assemblymember John Laird, is a

long-term solution that would keep our parks open.

However, there's a very long way to go before a final

budget is adopted and anything can happen in the

twists and turns of budget negotiations.

Is has been said somewhere that "There

has never been a good WAR or a bad PEACE." War is a

horrible human experience, disrupting world harmony and taking

the lives of young men and women before their time. The

United States of America was conceived in revolution, tested

in a great civil war, and tempered through its westward

expansion by armed conflict. Perhaps Thomas Jefferson

best summarized the inevitability of war, as well as its

desired outcome, in his letter to William Smith in 1787 when

he wrote:

Is has been said somewhere that "There

has never been a good WAR or a bad PEACE." War is a

horrible human experience, disrupting world harmony and taking

the lives of young men and women before their time. The

United States of America was conceived in revolution, tested

in a great civil war, and tempered through its westward

expansion by armed conflict. Perhaps Thomas Jefferson

best summarized the inevitability of war, as well as its

desired outcome, in his letter to William Smith in 1787 when

he wrote: Para

comprender mejor el contenido de esta web, se pueden leer los

siguientes artículos:

Para

comprender mejor el contenido de esta web, se pueden leer los

siguientes artículos: