|

Charles Gibson, an

eminent Latin American history scholar, once noted that “Spain in

America is a substantial subject …in space, time, and complexity it is

a more substantial subject than England in America,” adding

“ it carries an additional difficulty, for English-speaking

students, that it is alien and easily

misconstrued.”

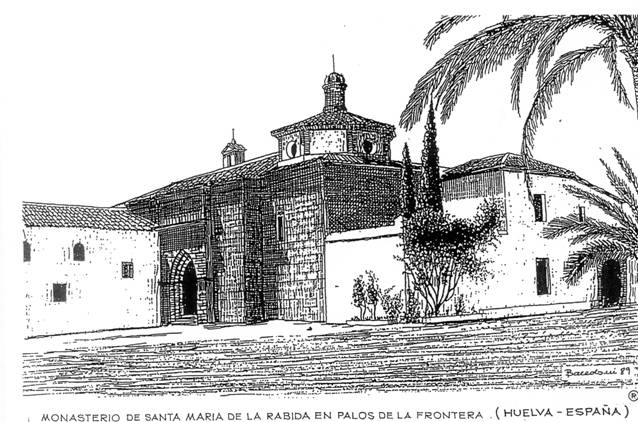

Charles Lummis, another historian,

said “If Spain had not existed 400 years ago the United States would

not exist today...the Spanish pioneering of the Americas was the largest

and longest and most marvelous fact of manhood in all of history.”

Christopher Columbus’ biographer, Samuel

Eliot Morison stated, “our forebears in Virginia and New England

were indeed stout fellows, but their exploits hardly compare with those

of the brown-robed friars and armored conquistadores who hacked their

way through solid jungles, across endless plains, and over snowy passes

of the Andes, to fulfill dreams of glory and conversion; and for whom

reality proved even greater than the dream.”

Another ground-breaking scholar who shared these views was Herbert

Eugene Bolton, a Wisconsin native

who received his Ph.D. in 1899 from the University of

Pennsylvania. In 1901 the University of Texas in Austin offered him a

temporary position to fill in for an ill faculty member of European and

Medieval studies. The faculty member later died and Bolton’s position

became permanent. The move

to Texas dramatically changed Bolton’s career.

He was allowed to teach the colonial history of Texas and went to

Mexico in search of sources. There he discovered untouched documents and

manuscripts that became the foundation of his life-long program of

research and writing in the field that came to be known, in his term,

the Spanish Borderlands. He quickly became the leader in the

field.

Bolton developed two basic concepts to revise the way in which

U.S. history was taught. First, he emphasized Spain’s primacy and

longevity in the Southern

tier of states especially in the Southwest. Secondly, he urged U.S.

historians to see U.S. history in a hemispheric context and that, in

essence, to properly understand American history a study of the Spanish

influence was necessary to obtain an accurate picture. Needless to say,

many historians disagreed with Bolton seeing the Spanish episode as a

small prelude to the emergence and dominance of England. Bolton received

criticism for his work, but he successfully initiated his program

developing over time many Ph.D. and masters level students who also

became prominent in the field, including Max L. Moorhead and John

Francis Bannon. In 1921 Bolton published The Spanish Borderlands, his signature work and the first of

many books and articles in the field.

In spite of Bolton’s significant contributions, the history of

Spain in America remains virtually unknown in textbooks and popular

histories. We live in an

English-speaking country with deep Protestant roots, and knowledge of

Spanish history in the United States, which is mostly Catholic, will

remain subordinated for a long time and little appreciated. Recently the

rise of Hispanic genealogical non-profit clubs and organizations in the

United States is bringing to the fore the fact that Hispanic explorers

and settlers in the Americas contributed significantly not only to the

development of Mexico and Latin America but to the United States as

well. One of the most active clubs is Los Bexareños Genealogical

Society from San Antonio, Texas. It

was founded by the late Gloria

Villa Cadena, the wife of deceased Chief

Judge Carlos C. Cadena,

one of the lawyers who won the landmark Hernandez

vs. Texas case before the Supreme Court. The court’s positive

ruling gave Hispanics and others the legal right to serve in juries

regardless of national origin. Today several members of the Los Bexareños

club are some of the best researchers of primary archival material in

Hispanic genealogy.

To understand the influence of Spain in America one needs to

begin with a review and perspective of the historical time periods in

the New World. Consider that

by the time Jamestown was founded in 1607, Spain had been in America for

over a hundred years. The English were able to settle on the East Coast

because that area had been bypassed by Spaniards as not containing

enough resources to make it worthwhile. By that time over 200,000

persons of Spanish and Portuguese descent were living in the New World.

Within fifty years of the founding of America, Spanish maritime

expeditions had already explored all the coast lines of North, Central,

and South America. Many towns, missions, and cathedrals existed, and a

university was in operation in Mexico City. There

were also missions up and down the East Coast, but few traces

exist because they were built

of wood and straw.

There was a Spanish mission operating about five miles from

Jamestown named Ajacán, established in 1566 and run by Jesuits. In 1571

a Christianized Native American and half-brother of Powhatan,

named Luis

de Velasco after a viceroy, killed several Spanish priests after

being rebuked for keeping too many wives. He had been born and baptized

in the Catholic faith and went to Spain twice and later to Mexico City.

He spoke Castilian and was on hand to meet the Jamestown settlers. He

helped them with farming, hunting, building shelters, and tribal

relations. He may have also

helped them determine the site of Jamestown. After

reverting to his primitive ways, Luis changed his name to Opechancanough

meaning “man whose soul is white.” Some historians believe that his

father may have been a Spaniard. The common illustration of savage

Indians coming out of a dark primeval forest to greet the pilgrims,

amazed at seeing white men,

is incorrect and mythological.

Another historical perspective that is not usually obvious about

American history is that the period from the discovery of America in

1492 to U.S. independence in 1776 consisted of a period of 284 years.

From 1776 to today, 2011, the time span is 235 years. In studying

history we forget this fact, thinking that our history started somewhere

shortly before the time of George

Washington. We are

not generally cognizant that significant historical events, mostly

Spanish, occurred during those prior 284 years, but our academic

inculcation of English history tends to consider those times, longer

than our modern period, as historical blanks.

Strange as it may seem, the first settlement in what is now the

United States proper was San Miguel de Gualdape established in Georgia

in 1526 by Lucas Vásquez de

Ayollón. Its exact

location is not known. Located in a swampy area, malaria, unfriendly

Indians, and homesickness doomed the settlement from the start much like

the struggle for survival by the Jamestown settlers. Two other Spanish

settlements predated Jamestown in 1607 and Plymouth in 1620. St.

Augustine was established in 1565 in Florida by Pedro

Menéndez de Avilés and is still in existence, as is Santa Fe, New

Mexico originally in another site

known as San Gabriel del Yunque founded in 1598

by Juan de Oñate.

The westward “Manifest Destiny” expansion in the United

States covered a period of perhaps 100 years from 1790 to 1890. This

period has been much glamorized in U.S. history in books, movies, and

television. If one asks an audiences to mention outstanding persons in

this era the answers usually include Jesse

James, Billy The Kid, Sam Bass,

and “Wild Bill” Hickok,

all outlaws and gunmen from the lower rungs of society. Perhaps

they may remember a more notable group such as Wyatt

Earp, Kit Carson, Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett,

and Buffalo Bill who did help

in some way to settle the West.

However, there was another movement from south to north in North

American history starting in 1521 when Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztecs and gained Spanish supremacy in

what later became New Spain. The following Spanish Colonial Period

lasted until 1821 when Mexico gained its independence from Spain.

This was a period of 300 years presided over by 62 viceroys, in effect

representatives of the Spanish kings. This expansion included two major

northward movements from Mexico City into what is now Texas and New

Mexico. The road to Texas and New Mexico followed what was referred to

as the Silver Trail.

After Mexico City fell, the Spaniards fought the savage northern

tribes known as Chichimecas for

control of the territories

in which of the cities of Guadalajara, Guanajuato, Zacatecas, San Luis

Potosi, Mazapil, and Saltillo were later established. The last major

outpost, Monterrey, in what is now Northern Mexico, was founded

September 20, 1596. It was the farthest outpost in the wilderness. To

the north was Texas, the unknown land. Ironically about the same time,

as previously noted, Juan de Oñate founded San Gabriel del Yunque in New Mexico. The northern

movement continued after Mexico became independent from Spain and all

told this expansion lasted 327 years. It is noteworthy that the two

movements merged in Texas. The buckskin-clad frontiersman met the

Mexican vaquero, borrowed his ranching knowledge and techniques, and the

lore of the heroic Western cowboy was born.

What happened in these Spanish and Mexican periods

significantly overshadows the history of the United States

western movement. In New Spain/Mexico the very same type of events were

going on that were experienced in the U.S. east to west migration. The

second and third wave of Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores fought

the northern tribes for supremacy in bloody and costly encounters.

Forts were built to stem the Indian tide and to protect property.

Ranches, farms, and towns were established by settlers, including those

for mining bases, with public officials elected to govern. The Catholic

religious orders established missions and schools and the wilderness was

slowly pushed back. The area triad of town, presidio, and mission was a

unique feature of Spanish settlements established to protect and bring

peace to a populated area.

In a speech before the Alamo in celebration of the Tejano heroes

who fought at the Alamo, Dr. Félix

D. Almaráz Jr., of the University of Texas at San Antonio, noted

that “for too long our people have been in the shadows of history.”

Some have seen the light and are recognized as Spanish “founding

fathers” of the Americas, men such as Juan

Ponce de León, Francisco Vázquez

de Coronado, Hernando de Soto,

Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, Francisco

Pizarro, and Vasco Núñez de

Balboa. There are, however, many men in the subsequent expansion of

the Spanish empire who are not household names as a result of the

suppression of Spanish and Mexican history in the United States. The

first viceroy in New Spain was Antonio

de Mendoza a capable

administrator followed by 61 others, many of whom were admired for their

competency.

In the colonial period are found many courageous and outstanding

men starting with those captains

who came with Cortés, such warriors as Gonzalo

de Sandoval, Cristóbal de

Olid, Pedro de Alvarado, Francisco

de Montejo and Diego de Ordáz.

Captain Andrés de Tapia,

was not in the immediate formal circle of Cortés, but was in fact his

most trusted and loyal officer. De Tapia reconnoitered the Aztec forces

in one of the most severe battles during the conquest and gave

intelligence information that helped Cortés to ultimately prevail. De

Tapia also wrote a short relación

or chronicle of the conquest. Another, Juan Rodíguez de Cabrillo, became the founder of California. In

later periods can be found secondary conquistadores

Diego de Montemayor founder of Monterrey, Luis de Carvajal de la Cueva governor of Nuevo León, Alberto

del Canto founder of Saltillo,

Alonso de León the Elder, a learned man,

who wrote the first history of what is now the state of Nuevo León,

and his son General Alonso de León

who led the first entradas (expeditions)

into Texas to find Fort St. Louis, established by René Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle. Francisco Martinez was de

León’s French interpreter and later helped found Pensacola, Florida.

Many notable men, too numerous to mention, can be found in

Spanish Texas such as Fathers Francisco

Hidalgo and Antonio Margil,

colonizers like The Marqués de Aguayo, and José

de Escandón. Escandon’s expeditions into Nuevo Santander, (now

Northern Tamaulipas state and

Southeastern Texas) led to the establishment of many towns and missions

in that area. Most important of those towns were the ones along the

present Texas/Mexico border founded between 1749 and 1755. The first was

Camargo founded by Captain Blas María de la Garza Falcón, followed by Reynosa

founded by Captain Carlos Cantú,

Revilla founded by Captain

Vicente Guerra, Dolores founded by Captain

José Vásquez Borrego, Mier

founded by Captain José Florencio de Chapa, and, lastly, Laredo founded by Captain

Tomás Sánchez. Other notables in early Texas were Governors Manuel

Salcedo, Domingo Cabello and

Joaquin de Arredondo, Spanish Commander at the Battle of Medina,

later Commandant of the Eastern Interior Provinces.

Arredondo suppressed the first attempt by filibusters to take

over Texas. An army styled the Republican Army of the North invaded

Texas and captured Goliad and San Antonio. This effort is sometimes

referred to in textbooks as the Gutíerrez-Magee Expedition after its

initial leaders Bernardo Gutiérrez

de Lara and Augustus Magee.

Arredondo, at the head of the last Spanish Army to fight in Texas, met

them south of San Antonio at the Battle of Medina, August 13, 1813. It

is the largest battle ever fought west of the Mississippi with over 800

casualties mostly from the rebel ranks. Arredondo took back San Antonio

and stayed for a year executing rebel sympathizers. In his report to Viceroy

Félix María Calleja, Arredondo praised several of his men for

bravery, including his protégé Lt.

Antonio López de Santa Anna, and

Lt. José Andrés Farías, who led the volunteers from Laredo.

Santa

Anna became familiar with the San Antonio area in this battle

twenty-three years before he laid siege to the Alamo. As the villain of

the later battle, he has been a caricature in Texas history and stereotypically

portrayed in film as a cruel, despotic and mad ruler. He was, in fact, a

very complex person, a capable student of Napoleonic military tactics,

and an abolitionist fighting against, not only rebellious Anglo Mexican

citizens, but other opportunists

who crossed illegally into Texas in search of fortunes and free land. He

was no more brutal than anyone of his time in any country.

The Alamo story is a classic example of glorified United States

history, whose defenders in the battle were supposedly fighting for

Texas liberty. The Alamo was not defended by soldiers but by merchants

and farmers, even abandoned by Sam

Houston and financiers seeking the

“liberty” of establishing a cotton empire supported by slavery.

Santa Anna’s generals advised him to bypass the Alamo and go on to

Goliad but his attack, uncharacteristically, was a mistake. Militarily,

the Alamo was inconsequential. Further, had the defenders and their

compatriots been more patient their lives could have been spared. The

land-hungry hordes of Manifest Destiny would have later overrun Texas

which Mexico, in its weak state, could not defend.

In his book Exodus from the Alamo: The Anatomy of the Last Stand Myth,

Philadelphia, 2010, author Phillip

Thomas Tucker uses extensive accounts from the Mexican and American

side to prove that the Alamo defenders did not all die inside the Alamo

in a heroic stand. Santa Anna surprised them in a pre-dawn attack and

some chose to stand, but about 260 men decided to flee and fight another

day running out the back of the mission. They were heading for the

Gonzales road that began in the area south of the Alamo known as the

Alameda. Santa Anna had anticipated such a move and had stationed his

elite lancers commanded by General

Joaquín Ramírez y Sesma to intercept them. All were killed as they

tried to escape and Thomas

proposes that the bodies of the defenders were burned on two sides of

the Alameda because that is where they fell and their bodies

could not have been dragged all the way from the Alamo.

There are other interesting aspects to the history and genealogy

of Hispanics in the New World. A

significant number of Mexican and U.S. Hispanics are descendants of

Portuguese and Spanish Jews, known as Sephardic Jews, who converted

voluntarily or forcibly to Catholicism during the persecution of the

Middle Ages. The Sephardim considered themselves the elite of Jewry in

Spain as the leading scholars, physicians, lawyers, financiers,

mapmakers, and merchants. Many early settlers of Northern Mexico,

particularly in Monterrey and Saltillo were conversos

(converts). Some were

called Crypto-Jews, openly Catholic, but practicing Jewish rites in

secret. They were the main target of the Inquisition, which also crossed

the Atlantic to the New World. A common ancestor is Abraham

Ha-Levi a great literary figure from a prosperous merchant family

from Burgos. His relative Salomon

Ha-Levi, the Chief Rabbi of Burgos, converted to Catholicism,

changed his name to Pablo de Santa Maria, and was elevated later to Bishop of Burgos.

Another unusual aspect of these Hispanic settlers is that many of

them were descended from the royal houses of Europe. Early persons who

arrived to take over the government of the land newly conquered by Cortés

were personally appointed and authorized to emigrate by King

Charles V of Spain who was also Charles

I, Holy Roman Emperor. Sensing that Cortés might establish himself

as a king in the New World, Charles quickly sent as officials only

members of his family, his court, or noble families known and loyal to

him. The first four officials to arrive to take over government reins

were Tesorero (Treasurer) Alonso

de Estrada, Contador

(Accountant) Rodrigo de Albornoz,

Veedor (Inspector) Pedro Almíndez Chirinos and Factor,

(Business Agent) Gonzalo de

Salazar. Estrada claimed to be an illegitimate son of King Ferdinand, Isabel’s husband,

but that is still in historical dispute. Salazar, however, is a

documented example of the ties

to royal lines. His daughter was Catalina

de Salazar, who married Ruy Díaz

de Mendoza from one of Spain’s wealthiest and most powerful

families and a descendant of Spain’s King

Alfonso line. She later married Cristobal

de Oñate, Juan de Onate’s father, who was one of the founders of

the rich Zacatecas silver mines along with three other men, Diego de Ibarra, Juan de

Tolosa and Baltasar de Temiño

de Banuelos. Another line comes from a descendant of Ruy Díaz de Vivar, El Cid,

Spain’s greatest national hero. His

descendants first came to Mexico City and later

passed to Monterrey with the marriage of Joseph de Treviño de Quintanilla and Leonor Ayala Valverde. There are numerous descendants of El Cid in

Mexico and the United States.

One more interesting fact, in the general history of the United

States, concerns three Hispanics who were instrumental in the success of

the American Revolution and without whose help our country would

possibly not exist today. Without the contributions of these men perhaps

the United States today would not be a dominant world power but rather a

third world country made up of Spanish, French, and English

post-colonial entities. The first notable person was George Washington,

whom historian Robert H. Thonhoff

terms, “the first Hispanic President of the United States,” since

Washington was a descendant of the Spanish queen, Eleanor

of Castile. Washington was the father of our country, not only for

winning the American Revolution against enormous odds, but for chairing

the constitutional convention that produced the greatest document

of freedom in the world. In addition, as our first president he set a

standard and protocol for the office that exists even today. Some

historians consider him to be the greatest man born in the last thousand

years worldwide.

The second notable Hispanic hero of the American Revolution was Bernardo

de Gálvez, who, in effect, was in command of the Southern Front in

the Revolution, although as an ally. He was field marshal of all the

Spanish armies in America. His successful performances enabled

Washington to concentrate his efforts in the East while George

Rogers Clark, with Spanish help also, fought on the Western Front. Gálvez

first came to the New World with his uncle, Minister of the Indies José

de Gálvez, who was charged with improving Spain’s fortifications

and administration in New Spain. His power was second only to King

Carlos III. Bernardo

arrived in Mexico in 1765 and became commandant of the army of Nueva

Vizcaya. He had already served in a campaign against Portugal and later

fought in France and Algiers. He fought the Apaches on the frontier and

once was wounded with a lance that pierced his chest. The Apaches left

him for dead but he miraculously recovered. In January 1777 he became

Governor of Louisiana. Spain did not enter the American Revolution until

May 1799 but Gálvez and his predecessor,

Luis Unzaga, supplied early aid to the rebel forces through private

merchants.

One day Unzaga received a letter from General

Charles Lee, Washington’s second in command, that Fort Pitt was

under siege and desperate for help. In an anguished plea, Lee closed the

letter by stating, “in the name of humanity, please help us!” Unzaga

sent food, medicines and, by one account, over 10,000 rounds of

ammunition. The supplies went up the Mississippi and the Ohio River.

They arrived in time and Fort Pitt was saved. Spain’s contributions to

the Revolutionary War effort have been minimized but in fact Spanish

financial aid and supplies enabled Washington to win the war. As an

example, in one shipment on September 1776 Spain contributed 216 brass

cannon, 209 gun carriages, 27 mortars, 29 couplings, 12,826 shells,

51,134 bullets. 300,000 boxes of gunpowder. 30,000 guns with bayonets,

4,000 tents and 30,000 suits.

Since Gálvez had served in the Northern Spanish Frontier, he

knew of the tremendous herds of cattle in Texas, which were then sold

mainly for hides and tallow. He requisitioned beef for his forces from

Texas ranchers, primarily those that operated between San Antonio and

Goliad along the San Antonio River. Besides cattle that belonged to the

Spanish missions, large herds were maintained by private ranchers, with

surnames such as de la Garza,

Tarin, Piscina, Arocha, Montes de Oca, Seguin,

Martínez, González, Chapa, Gutíerrez, Rodríguez, Gortari, Delgado,

and Rivas. The descendants of these ranchers are qualified to become

members of the Sons of the American Revolution. One hundred years before

the “famous” cattle drives from Texas such as the ones up the

Chisholm Trail to the Kansas railheads, Tejanos made numerous cattle

drives to Louisiana to supply Gálvez.

After Spain entered the War, Governor Gálvez launched his

campaigns against England. He defeated the British all up and down the

Mississippi and then turned his attention to the Gulf. The Battle of

Pensacola, where he uttered his famous cry “Yo Solo” ( I alone), is

considered the greatest naval battle of the American Revolution. Since

Pensacola Bay had a narrow entry with cannon placements, Gálvez’

admirals hesitated to enter. Gálvez

shouted they would enter if “he alone” went in and that encouraged

his men to follow him.

A little known fact is that Gálvez’ father, Matias

de Gálvez, was fighting the British at the same time in

Central America. England was trying to take over the area primarily to

split North America and South America. In addition, Central America had

many natural resources and control was necessary to transport goods

overland between the Atlantic and The Pacific oceans. Matias also

defeated the British and expelled them from that theatre of war. Father

and son Gálvez never lost a battle to English forces.

One final anecdote about the contributions of Gálvez to winning

the American Revolution concerns the final days when Washington was

moving to corner the British at Yorktown, The American and French

soldiers were refusing to

fight because they had not been paid in months. Washington sent an

urgent appeal to Gálvez for a loan. Gálvez sent the request to

Governor Juan M. Cagigal in

Cuba. A loan was arranged and a call went out to the Cuban people to

also contribute. Two French

ships were sent by Gálvez since he was technically in command of the

French fleet in America. It is said that the Cubans contributed arms,

munitions, and clothing and even personal items of gold and silver. Washington

reportedly filled two warehouses with the goods. The soldiers were paid

and with the blockade of the sea by the French navy under Admiral

Francois-Joseph Paul de Grasse, Washington dealt the final blow to

British troops, paving the way for a new and independent nation. We

owe Cubans a debt of gratitude.

The third notable Hispanic, lesser known, but crucial to winning

the Revolutionary War was a Portuguese lad named Peter

Francisco abandoned on the shores of America on June 23, 1765.

He was taken in as an indentured servant by

Judge Anthony Winston, an uncle of Patrick

Henry. He was outside

the window of St. John’s Church when Henry gave his stirring “Give

me liberty or give me death” speech. Excited by Henry’s oratory,

Peter begged Judge Winston to let him join the Continental Army, but he

was only 15 years old. Even then he had grown to a large size and was

very strong. A year later Judge Winston relented, and Peter joined

the army. He was first wounded at the Battle of Brandywine, and he

recuperated next to a young general, the Marquis

de Lafayette, also wounded in that battle. They became life-long

friends.

Peter fought in almost every major battle of the Revolution and

was a legend in his time. It is said you could not sit by campfire

without listing to stories of his exploits. He was wounded six times,

two almost fatally, and he was a hero in peacetime also, at one time

carrying armfuls of people from a disastrous theater fire in Richmond,

Virginia. He was six-foot-eight and described as the Virginia Giant.

Some historians believe him to have been the strongest man in America

and consider him the greatest soldier who has ever served in U.S.

forces. Peter had been kidnapped and never

knew where he came from but recent historians have traced him to

Terceira Island in the Azores. Washington said of Peter, “Without him

we would have lost two crucial battles, perhaps the War, and with it our

freedom. He was truly a One-Man Army.”

One significant factor in diminishing and criticizing

the role of Spaniards in history

is called the Black Legend. La

Leyenda Negra consists of historical writings and attitudes that

demonize Spain and its empire and was created to incite animosity

against Spanish rule. It carries the connotation that Spain’s role in

the Americas was not important and did not contribute anything

worthwhile. One example says that the conquistadores were extremely

cruel killing thousands of Indians in sadistic fashion and had to

demonstrate their superiority in ugly and oppressive acts. The Black

Legend says that no military necessity justifies such acts and the only

possible explanation lies in a national psychological perversion.

Spain’s response is termed the White Legend, La

Leyenda Blanca. The Spaniards rebut that these stories have been

developed by enemies of Spain without looking at the true facts. While

such acts of extremism occurred, they happened on both sides, as in all

wars, and were indicative of the entire age. With respect to cruelty,

Spain has a better record than England, which virtually exterminated the

Indians in their colonies in one of the most lethal and determined

programs of ethnic slaughter on record. And the English, unlike the

Spanish, never expressed any feelings of guilt or questioned the ethics

of their imperial conduct. Spaniards made citizens of their Native

American subjects, assimilated by marriage with many of the advanced

tribes, and educated them. Indian women had rights and were educated

hundreds of years before other American women received equal

treatment.

This denigration of Spain and its people can be traced back to Queen

Elizabeth I, a bitter enemy

of Philip II, especially

after the Spanish Armanda was launched but failed to accomplish its

goals. The Catholic versus Protestant conflict figured prominently in

the alienation of the two countries. Elizabeth envied the territories

and riches of Spain, already a world power when England was still a

pastoral agricultural country emerging from the Dark Ages. She was, no

doubt, a worthy opponent and she set her pirates, mainly the fleets of Francis

Drake and John Hawkins,

to infringe on Spanish territory and capture their ships loaded with

gold and silver on their way to Europe. Spain was unable to defend such

a large worldwide territory and the English, French and Dutch

consistently harassed Spanish territories. The Bank of England, and in

fact, the British Empire, were established and built from stolen Spanish

gold and silver.

While Queen Elizabeth I was a shrewd and gifted ruler, her

accomplishments pale in comparison to Queen Isabel, La Catolica,

who brought Spain into the

modern world. She came seemingly out of nowhere and was perhaps

spiritually guided because what she accomplished in her lifetime

staggers the imagination, perhaps making her the greatest woman born in

the last thousand years. She had the knack of always selecting the right

person for the job. Her husband, Ferdinand,

was a sly and crafty politician who helped her unite Spain. She broke

the power of the nobles, cleaned up criminal gangs ravaging the

countryside, reformed the Catholic Church, expelled the Moors after a

campaign against Granada that lasted ten years, and encouraged

Christopher Columbus in his quest. She assisted her husband and her

“Great Captain,” Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba-the greatest soldier of his age-as fundraiser

and quartermaster helping them lead her armies to victory. Even when

pregnant she would ride for

miles on horseback discharging her duties. She is a great role model for

Hispanic women.

It should be said prior to closing that we are indeed fortunate

to live in the United States, a country which Abraham

Lincoln referred to as “the last

best hope on earth.” Historians seem to agree that the greatest

Americans who ever existed all lived in the colonial period. One gets

the sense that The Almighty or “ Divine Providence,” to use

Washington's normal phrase, also guided

the birth of the United States.

One of the great feats of the English has been to expertly market

their history, language and culture. Erecting statues and monuments of

its heroes everywhere, using propaganda,

and various forms of media,

England appears to be a favored nation to be envied by all. Its

literature, dialects, accents, gardening, tea socials, and breakfasts

are indeed appealing. Its dominance in the establishment and expansion

of the United States perpetuates

the myth of English superiority. The histories and cultures of Spain,

Portugal, France and the Netherlands, closely studied, are just as

interesting and fascinating.

I would be remiss if I did not give England credit for its great

legal contributions to justice. The Magna

Carta, the jury system, and the golden thread that runs though the

English judicial system, “ the presumption of innocence,” are

bulwarks of our freedom and human rights. But it should be equally noted

that Spanish law, especially in the Southwestern United States, extended

the body of rules that produced a better quality of life for our

citizens. In Texas, for example, Anglo Texans incorporated facets of the

Castilian system of civil courts. Spanish legal influence has prevailed

in probate matters, land and water rights, women’s rights, and in

family law, such as adoption, which was previously unknown under English

law.

With the possible exception of William

Shakespeare, Miguel de

Cervantes and other Spanish writers have produced as much a body

of outstanding qualitative material as England’s scribes. It is

unfortunate that Spanish literature has not received proper recognition

in academic studies and students are not generally aware of its lyrical

beauty. Those who understand

Spanish and are intimately acquainted with its classic prose and

poetry can attest that it rivals any language for sheer

excellence.

As we have shown herein, Spain in America is a very substantial

and profound subject, with heroic

events in our country’s historical evolution, and Hispanics can relish

the accomplishments of their

forebears. They can assume an equal station in the assessment of their

culture and can take great pride and esteem in the many outstanding and

brilliant Iberian men and women who helped

evolve a vibrant modern world.

© Copyright, 2011

George Farias

San Antonio, Texas

|

MENDING

THE SACRED HOOP is committed to strengthening the

voice and vision of Native peoples. We work to end violence

against Native women and children while restoring the safety,

sovereignty, and sacredness of Native women. We work from a

social change perspective that relies upon grassroots efforts

to restore the leadership of Native women.

MENDING

THE SACRED HOOP is committed to strengthening the

voice and vision of Native peoples. We work to end violence

against Native women and children while restoring the safety,

sovereignty, and sacredness of Native women. We work from a

social change perspective that relies upon grassroots efforts

to restore the leadership of Native women.

Ken Salazar urges more Latino-themed national

parks

Ken Salazar urges more Latino-themed national

parks

There is no doubt that Gerrymandering is dirty politics, perhaps because there are 435 House seats at stake. Despite a mantric call for greater transparency and public accountability, American politics seems mired in the traditional rut of politics-as-usual which will carry over to redistricting per the 2010 Census. The spirit of fair play has never been a virtue of American politics. To expect “fair play” in the current round of redistricting may be a velleity. Perhaps we should just accept the proposition that “all’s fair” in love, and war, and politics. But we should always be vigilant since vigilance is the price of freedom as the American Civil Liberties Union reminds us.

There is no doubt that Gerrymandering is dirty politics, perhaps because there are 435 House seats at stake. Despite a mantric call for greater transparency and public accountability, American politics seems mired in the traditional rut of politics-as-usual which will carry over to redistricting per the 2010 Census. The spirit of fair play has never been a virtue of American politics. To expect “fair play” in the current round of redistricting may be a velleity. Perhaps we should just accept the proposition that “all’s fair” in love, and war, and politics. But we should always be vigilant since vigilance is the price of freedom as the American Civil Liberties Union reminds us.

Eliseo Diaz and Juan Rodriguez were just two normal guys — entrepreneurs, mind you, but normal guys nonetheless — who were living out their lives in Austin, Texas earlier this year when an opportunity presented itself to them in a most unlikely way. Now the two Dominicanos are focused on their burgeoning mobile business, Flash Valet, which at once makes valet parking high-tech, and easier to deal with.

Eliseo Diaz and Juan Rodriguez were just two normal guys — entrepreneurs, mind you, but normal guys nonetheless — who were living out their lives in Austin, Texas earlier this year when an opportunity presented itself to them in a most unlikely way. Now the two Dominicanos are focused on their burgeoning mobile business, Flash Valet, which at once makes valet parking high-tech, and easier to deal with.

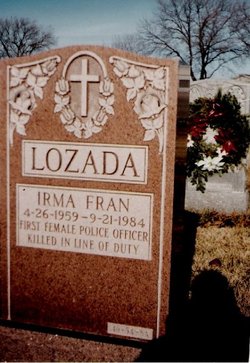

Police Commissioner

Police Commissioner

On a day in the 1840s, Lorenzo Trujillo sucked the poison from an arrow wound in the shoulder of the man known as Don Benito Wilson, just after a violent battle with a Native American named Joaquin in narrow canyon near the Mojave River. Joaquin and his followers had stolen horses again and again, defiant and successful, and the

Trujillos' job was to recover the livestock.

On a day in the 1840s, Lorenzo Trujillo sucked the poison from an arrow wound in the shoulder of the man known as Don Benito Wilson, just after a violent battle with a Native American named Joaquin in narrow canyon near the Mojave River. Joaquin and his followers had stolen horses again and again, defiant and successful, and the

Trujillos' job was to recover the livestock.  The Native Americans of Salt Lake, of Nevada, and of the Mohave River area made forays "every full moon," according to California historians, especially Chief Walkara of the

Utes. Trujillo was given land in exchange for "protection against thieves and marauders of every hue." (A few years later, when the Gold Rush ran out of gold, bands of broke Texans worked their way along the Inland ranchos and stole everything from trunks to blankets to food and horses.)

The Native Americans of Salt Lake, of Nevada, and of the Mohave River area made forays "every full moon," according to California historians, especially Chief Walkara of the

Utes. Trujillo was given land in exchange for "protection against thieves and marauders of every hue." (A few years later, when the Gold Rush ran out of gold, bands of broke Texans worked their way along the Inland ranchos and stole everything from trunks to blankets to food and horses.)  The settlers dug irrigation ditches and canals, planted grain, grapes, and raised livestock. It seemed like paradise, and plenty of immigrants thought so, too.

The settlers dug irrigation ditches and canals, planted grain, grapes, and raised livestock. It seemed like paradise, and plenty of immigrants thought so, too.

Downtown West Liberty, Iowa, is quintessentially Midwestern American, both quaint and historic, with brick buildings lining brick streets. A typical stroll involves walking past the bank, a renovated theater, a hair salon, restaurants and stores.

Downtown West Liberty, Iowa, is quintessentially Midwestern American, both quaint and historic, with brick buildings lining brick streets. A typical stroll involves walking past the bank, a renovated theater, a hair salon, restaurants and stores. "When I arrived here in '84, they told me that such and such businessman wouldn't allow it, like for instance, the bar owners, wouldn't allow Mexican customers there, or they despise them openly, or things like that," Zacarias says.

"When I arrived here in '84, they told me that such and such businessman wouldn't allow it, like for instance, the bar owners, wouldn't allow Mexican customers there, or they despise them openly, or things like that," Zacarias says.

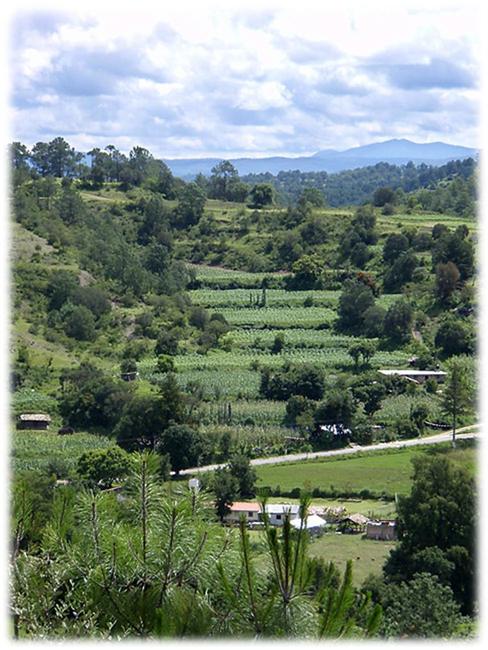

Jesús León y sus amigos impulsaron un programa de reforestación. A pico y pala cavaron zanjas-trincheras para retener el agua de las escasas

lluvias, sembraron árboles en pequeños viveros, trajeron abono y plantaron barreras vivas para impedir la huida de la tierra fértil.

Jesús León y sus amigos impulsaron un programa de reforestación. A pico y pala cavaron zanjas-trincheras para retener el agua de las escasas

lluvias, sembraron árboles en pequeños viveros, trajeron abono y plantaron barreras vivas para impedir la huida de la tierra fértil. Cada día hacen retroceder la línea de la desertificación.

Cada día hacen retroceder la línea de la desertificación.

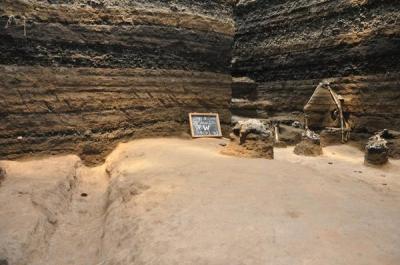

The earliest people in the Americas were people of the Negritic African

race, who entered the Americas perhaps as early as 100,000 years ago, by

way of the bering straight and about thirty thousand years ago in a

worldwide maritime undertaking that included journeys from the then wet

and lake filled Sahara towards the Indian Ocean and the Pacific, and

from West Africa across the Atlantic Ocean towards the Americas.

The earliest people in the Americas were people of the Negritic African

race, who entered the Americas perhaps as early as 100,000 years ago, by

way of the bering straight and about thirty thousand years ago in a

worldwide maritime undertaking that included journeys from the then wet

and lake filled Sahara towards the Indian Ocean and the Pacific, and

from West Africa across the Atlantic Ocean towards the Americas.

After seeing the Miss Universe beauty pageant this year and viewing the proclamation of a beauty from Angola as the Miss Universe, my curiosity and interest have then started to shift to the former Portuguese colonies in Africa.

After seeing the Miss Universe beauty pageant this year and viewing the proclamation of a beauty from Angola as the Miss Universe, my curiosity and interest have then started to shift to the former Portuguese colonies in Africa.