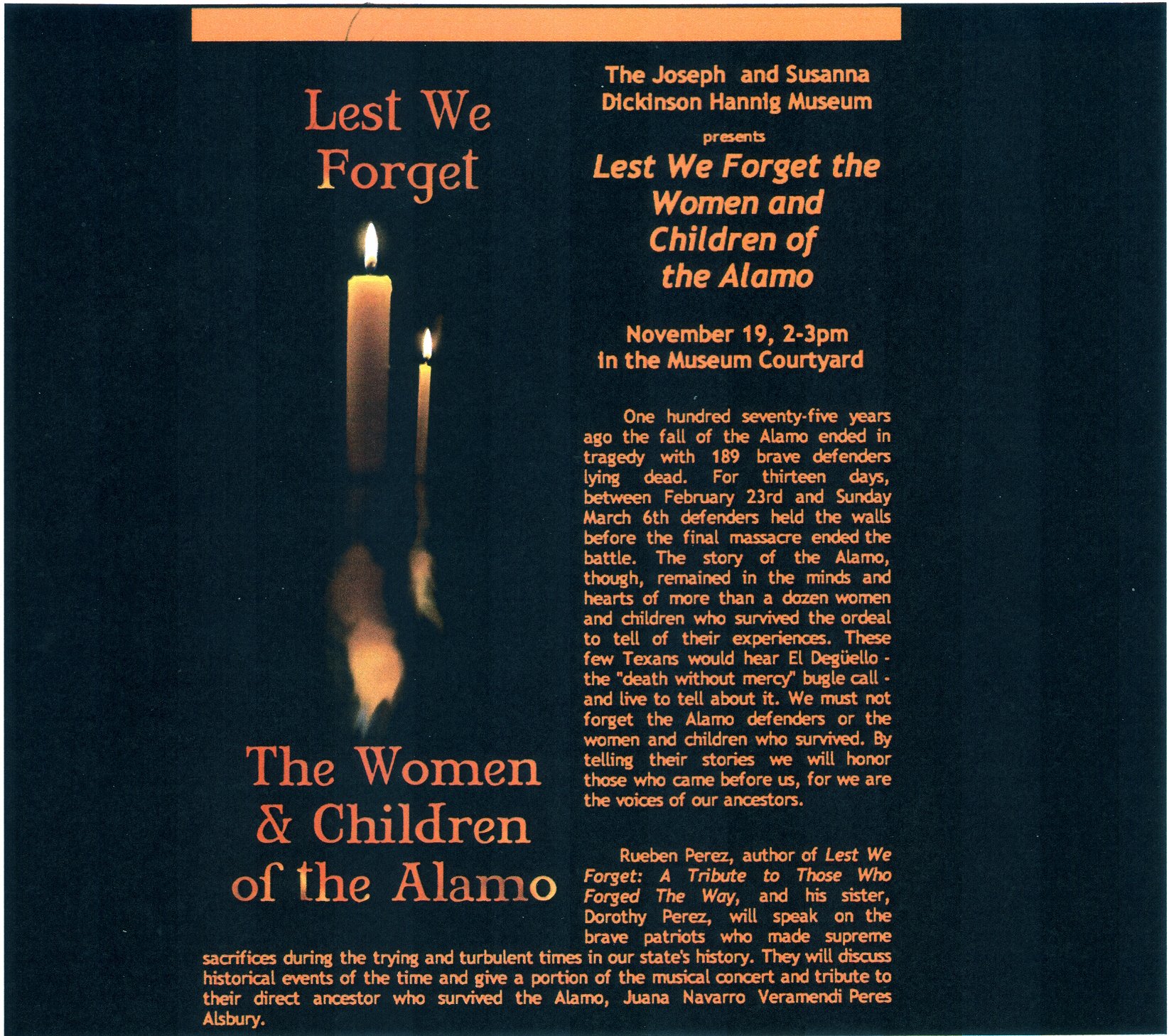

LEST

WE FORGET THE WOMEN OF THE ALAMO

The following is a presentation made on November 16, 2011 at

the Joseph and Susanna Dickinson Hanning Museum in Austin, Texas.

The presenters were Rueben M. Perez and his sister Dorothy M.

Perez.

OPENING

INTRODUCTION:

When I was in fifth

grade elementary school we had classes in Texas History.

For a young person it was pretty exciting learning about

Texas History and the Battle of the Alamo.

However, I felt something was wrong and the picture of the

stories that I heard at home was different from what the teacher and

the books were saying. My

mother and I would pick my father up from work at the Post Office

directly across the street from the Alamo.

He would always say, over there is where your great great

grandmother and great grandfather were during the Battle of the

Alamo. Yet, that was

not what I was hearing at school.

They would only talk about Susanna Dickinson and her daughter

as survivors of the Alamo and in passing mention there were Mexican

women and children. It

was not until much later in life that I would know whom those other

women and children of the Alamo and come to appreciate my heritage

even more.

Today, history is in

the making being at the Joseph and Susanna Dickinson Hanning Museum

and having the opportunity to recognize all of the women and

children who were involve in the Battle of the Alamo.

One of the women is our great great grandmother, Juana

Navarro Veramendi Peres Alsbury.

Little has ever been mentioned as to who she really was.

To provide a quick background on Juana, her grandfather was

from Corsica. Her

father, Angel Navarro was in the Spanish Army and later responsible

for saving the Spanish Archives, signing the Bexar Remonstrance to

separate Texas from Coahuila, proclaimed independence from Spain as

Politico Jefe (mayor), and was Politico Jefe up to December 1835

prior to the fall of the Alamo.

The history books failed to recognize the Governor of Texas,

Juan Martin Veramendi had legally adopted Juana and that her

stepsister Ursula Veramendi was the wife of James Bowie.

Nor was it ever mention that her great uncle, Francisco Ruiz

was one of the only two native Texans to sign the Declaration of

Independence of Texas and her uncle, Jose Antonio Navarro, was the

only man to sign the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution.

All together, there were six family members in the Alamo,

Juana Navarro, baby Alejo E. Peres, sister, Gertrudis, Juana’s

husband who left, Dr. Horace Alsbury, brother-in-law James Bowie,

and Manual Peres, Mexican Army and brother in law to Juana.

As we honor and tell the story of Juana, we must not forget

the other brave women and children of the Alamo.

PROGRAM:

From the little Villa of San Fernando and the Royal Presidio

of San Antonio de Bexar, Province of Texas, the New Philippines the

words “Remember the Alamo” was heard around the world.

The call for independence was once again heard, as it was

earlier in the Texas connection to Mexico’s Independence.

One of the biggest battles that took place on Texas soil was

the Battle of Medina when Spanish Royalist forces under Joaquin de

Arredondo defeated the Republican Army of the North south of San

Antonio on August 18th, 1813.

Over 1,800 Spanish troops fought Colonel Bernardo Gutierrez

de Lara Republican Army of 1,500.

With the exception of a few who escape, those not killed on

the battlefield were captured and returned to Bexar and executed

daily at Military Plaza in San Antonio.

The remaining bodies lay on the battlefield without a burial

for 9 years. More lives

were lost in this battle than was during the entire battle of Texas

Independence.

Little is ever

mention about the over 300 women who were rounded up in Bexar

accused of having relatives supporting the rebel cause.

They were imprisoned, humiliated, and enslaved in La Quinta

for 54 days. Many

suffered daily lashes, forced to work making tortillas for the

soldiers while their children were in the streets begging for food.

The price was steep for the women who lost their husbands in

the battle or captured and executed.

Many families

fled and later had their homes confiscated for not being loyal to

the Spanish Crown.

Twenty-three years later, this scenario was to be repeated.

Brave men and women would help forge the history of Texas at the

Battle of the Alamo. We

must tell their stories, become their voices and remember their

heroic efforts. Our

brave patriots made supreme sacrifices during the trying and

turbulent times in our state’s history. Many of our ancestors

played an important role in the quest for Independence of Texas from

which we gain freedom and opportunity that we still enjoy in our

country today. Yet

after 175 years the brave women and children remain largely unknown,

unsung, and unhonored. Those

who fought and died at the Alamo have become legendary heroes and

the siege and Battle of the Alamo means many things to many people,

for those of us who are direct descendants, that page in history

becomes more meaningful.

During the first Alamo Descendant Association meeting in

1995, inside of the Alamo Chapel, the grandson of Alejo Perez, the

youngest survivor and the last to die in 1918 stepped up to the

podium to give the opening prayer.

With tears in his eyes, his voice quivering and unable to

conclude the prayer, this person had been born just early enough to

know as a child his grandfather, an Alamo survivor.

The distance of time seemed suddenly much shorter, as there

stood a person who knew someone who had been in the 1836 battle.

It was as close as most of us would ever be to the people and

the event. This person

was our father.

Families have since been bonded together to honor their

ancestors, the brave patriots who left their blood or legacy at the

Alamo on that cold Sabbath morning, March 6th, 1836.

One hundred seventy five years ago the fall of the Alamo ends

in tragedy with 189 brave defenders lying dead after the siege and

fall of the Alamo. After

thirteen days in February 23rd to Sunday March 6th the

final massacre within the walls ended.

The story of the Alamo remained in the minds and hearts of

all of us and for those who survival the ordeal to tell of their

experiences. Only a few

on the Texas side would remember the sound of the bugle, the

deguello, “death without mercy” and live to tell about it.

Frightened, scared and facing the unknown, their lives would

be changed on that fateful day.

We must not forget the Alamo defenders or the women and

children who survived. Their

stories will be told and we will honor those who came before us, for

we are the voices of our ancestors.

On this special occasion we would like to take the time to

celebrate and respectfully honor the women and children of the

Alamo. The brave and

gallant women who sustain enormous trauma, stress, and for those who

had lost their husbands in the supreme sacrifice made for

Independence.

There were women

and children, a dozen or so of them.

To this day, no one knows exactly just how many or who they

were all were. What we

do know is that their lives were all changed.

Let

us take a moment to remember and honor the brave women and children

of the Alamo.

WOMEN

AND CHILDREN OF THE ALAMO

JUANA

NAVARRO PERES ALSBURY

SUSANNA

DICKINSON

ANGELINA

ELIZABETH DICKINSON

ANA

SALAZAR ESPARZA

ENRIQUE

ESPARZA

FRANCISCO

ESPARZA

MANUEL

ESPARZA

MARIA

DE JESUS CASTRO ESPARZA

PETRA

GONZALES

CONCEPCION

CHARLI LOSOYA

JUAN

LOSOYA

JUANA

LOSOYA MELTON

GERTRUDIS

NAVARRO

ALEJO

PERES

BETTIE

VICTORIAN

DE SALINAS

ANREA

CASTANON VILLANUEVA |

24 years old

22 years old

15 months old

33 years old

8 years old

3 years old

5 years old

10 years old

unknown

57 years old

unknown

20 years old

20 years old

11 months old

unknown

and three daughters

50 years old

|

The past is always

with us; we must not let it escape.

The stories of our brave ancestors must be recorded, told and

re-told for future generations.

Lest we forget those who forged our history.

We are the voices of our ancestors.

Let neither their names, nor their life stories remain locked

in the tombs of the archives. Honor

them; respect them, for they are the brave souls who preceded us,

gave us the freedom and the life we enjoy today.

Their voices can no longer be heard, for they are gone in the

annals of history. As

we move forward in time, we take this moment to remember those who

went before us. We are

now the voices of the past. We

must continue to tell their stories about their lives, their

accomplishments and let their stories be told to future generations.

We honor and memorialize Texas brave and notable men, women,

and children of the Alamo. On

this special occasion, we will honor a noted Tejana woman and Alamo

survivor, Juana Navarro Veramendi Peres Alsbury.

As we do, she will represent all of the brave women whose

lives encumbered the

rich heritage and history of our State.

Her family came from afar, over the dusty trails of Texas to

carve a place in the history of San Antonio and Texas.

Juana Navarro was born on December 28, 1812 in Villa de San

Fernando de Bexar to the parents of Jose de los Angel Navarro and

Concepcion Cervantes Peres. The

time was during a period of unrest for the settlers of New Spain and

the Provincial of Texas. The

American colonies won their independence from the British, now the

Spanish Colonies were seeking their freedom and independence from

Spain. Shortly

after Juana’s birth, storm clouds gathered.

Her father, Angel Navarro was in the Spanish Army but later

discharged for taking the revolutionary side of independence.

Shortly after Juana’s birth, the Battle of Medina occurred

south of San Antonio on August 18, 1813.

The lives of Texas residents would become chaotic, a schism

would divide their loyalty, but they would continue the quest for

freedom.

The changing winds, storms and the quest for freedom in the

new world ravaged the citizens of Bexar.

Many fled before the Battle of Medina and later returned to

find their homes and property confiscated.

Juana was five years old when her father separated from

her mother who was no longer able to care for the children.

He took Juana to live at the Veramendi Palace, home of Juan

Martin Veramendi, Governor of the Province of Texas and Maria Josefa

Navarro Veramendi. They

adopted Juana as their own and she would grow up with her

stepsister, Ursula Navarro Veramendi.

The

Veramendi’s Palace backed up on the banks of the San Antonio River

and many stately guests and dignitaries would be entertained at the

Veramendi’s home where Juana grew up with Ursula.

The aristocratic Spanish, Mexican officials held formal

events at the Palace, along with newly arrived Texans.

One noted visitor to the Veramendi Palace would capture the

eye of Juana’s stepsister, Ursula, and he would be James Bowie.

The childhood and

adolescent life for the girls was good as they grew up.

As children, they would play on the back porch of the

Governor’s Palace, and cool off in the San Antonio River during

the extreme heat.

Fredrick Chabot said, “If the walls of the Veramendi Palace

had ears, and the walls of the Veramendi House had also a mouth to

talk, both could tell stories of romance, war, battles, politics and

death that would fill volumes of Texas Tales”.

Both Ursula and Juana would fall in love and marry their

loves; Ursula Veramendi married James Bowie and Juana, married Alejo

Peres both in San Fernando Church.

Juana’s marriage certificate read, Dona Maria Juana de

Beramendi, adopted daughter of Don Juan de Beramendi and Dona Maria

Josefa Navarro. One can

imagine the many nights the girls whispered in each other ears about

their love ones. Later

a child would be given to Juana, his name Alejo De La Encarnacion

Peres.

The storm clouds

would again ravage the land and the people, this time, not in war,

but Cholera. The days

ahead of Juana would be the most difficult she ever experienced in

her life, tragedy would strike the Veramendi family.

Juana lost her adopted parents, stepsister, Ursula, and later

her husband due to Cholera.

In October 1835, Juana with little Alejo, less than a year

old would witness the Siege of Bexar; Texas had begun the struggle

for independence. This

time the foe was not Spain, but the Republic of Mexico.

Juana married her second husband Dr. Horace Arlington Alsbury

following the Siege of Bexar in January 1836.

The winter storm clouds gather as the air turned colder,

further turmoil would mount and the Battle of the Alamo would occur

soon.

Tension mounted throughout the state, word had spread that

Santa Anna has started his invasion of Texas in February 1835.

On February 13, 1836, Santa Anna’s army was delayed by a

snowstorm in northern Coahuila.

Residents of Bexar were again frightened of what laid ahead

of them. Dr. Alsbury,

Juana’s husband, would leave his new family entrusting them to

James Bowie as the Mexican Army entered Bexar.

He departed for Gonzales to warn the settlers of Gonzales and

to seek reinforcements for the Alamo. Dr. Horace Alsbury was the

interpreter and spy assigned to capture Santa Anna under Capt. John

York’s Company of the Texas Republican Army.

James Bowie would take Juana, baby Alejo, and sister,

Gertrudes to the Alamo for protection.

The time is drawing near, drums beating from a distance, men

marching to the cadence, weary after a long trip.

The Mexican troops finally entered Bexar.

This battle was the one the world would remember forever, a

battle that would be written up in the annals of time and reach all

over the world and remembered in our hearts, “REMEMBER THE

ALAMO”. James

Bowie, brother-in-law would take Juana, along with baby Alejo, and

Gertrudis, sister to the Officer’s Quarter in the Northwest sector

of the Alamo perimeter.

The nights and days move slowly from February 23rd

to that dreadful day. The

people of Bexar were all in a panic. The Mexican troops were upon

them, as they would see the campfires of the troops glowing in the

cold night air. The

soldiers on both sides tense, their honor at stake, their lives on

the line and all knew what was ahead.

The

following is an actual account of Juana’s interview in her own

words, as recorded by John S. Ford.

Juana

to John Ford: “

Colonel Bowie was very sick with typhoid fever. A couple of soldiers

carried him away, he said, Sister, do not be afraid, I leave you

with Col. Travis, Col. Crockett, and other friends.

They are gentlemen, and will treat you kindly.

I saw him two or three times and the last time was three days

before the fall of the Alamo.

“ I do not know who nursed him after he left our quarters,

there were people in the Alamo I did not see.

My sister and I were in a building over there, we saw little

of the fighting, I peeped out and saw the surging columns of Santa

Anna assaulting the Alamo on every side, I could hear the noise of

the conflict- the roar of the artillery, the rattle of the small arm

– the shouts of the combatants, the groans of the dying, and the

moans of the wounded.

The fighting stop, I realized the Texians had been

overwhelmed in numbers.

“I asked my

sister, Gertrudes to open the door, when she did, she was greeted by

offensive language by the soldiers.

The tore her shaw from her shoulders.

I had my baby up against my chest, thinking to myself that he

would become motherless soon.

The

soldiers shouted to Gertrudes, YOUR

MONEY AND YOUR HUSBAND, she told

them, “I HAVE NEITHER

MONEY NOR HUSBAND”.

Juana went on to say

“A sick man came up to me, I think his name was Mitchell, he was

trying to protect me when the soldiers bayoneted him at my side.

After that a young Mexican who the soldiers were after,

seized me by the arm, trying to protect himself.

His grasp was broken when four or five bayonets plunged into

his body and many balls entered his lifeless corpse.

The soldiers broke open my trunk and took money and clothes,

also the watches of Col. Travis and others.

Juana

continued: “A

Mexican soldier came over and excitedly inquired:

“How

did you come here?” “What are you doing here any how?”

“Where is the entrance to the fort?” Stand here by this cannon,

I am sending for President Santa Anna.

Soon, another officer came up and asked, “What are you

doing here?”

“A

officer ordered us to remain here, and he would have us sent to the

President”

At that

moment, the officer said: “President!

The devil. Don’t

you see they are about to fire that cannon? Leave.”

They were moving away when they heard a voice calling

–“Sister.” as he approached her, he said, “Don’t you know

your own brother-in-law?”

Juana

said: “It was Manual Peres, my first husband’s brother, I told

him, “ I am so excited and distressed that I scarcely know

anything” “ he placed us in charge of a black woman belonging to

Col. Bowie, and we went to our father’s house in safety.

Juana

finished her interview with Ford: “ To my best remembrance, I

heard firing at the Alamo to twelve o’clock that day.”

Juana witnessed Texas

going from the Republic of Mexico to the Republic of Texas.

Tensions continued between both countries.

Again Juana would face further hardships when, Dr. Alsbury

was captured at the Bexar County Courthouse during the Woll’s

Invasion and imprisoned in Mexico.

She and Alejo, along with 150 family members traveled to

Candelia, Coahuila, Mexico to await their loves ones release from

Perote Prison. Dr.

Alsbury was released from prison and around 1847 was killed during

the Mexican-American War. Juana

went to live at San Juan Mission with Alejo.

He married Maria Antonio Rodriguez and joined the Confederacy

and later married a second time and had grandchildren from both

marriages.

Life had taken its toll on Juana, as it did on so many others

brave and heroic women of Texas who helped forge the way and stand

behind their principles. She

had lived life as princess, endured the turbulent times of Texas

history, and was now reduced to a frugal existence in her later

years. Her only

son, the youngest baby, became the last living survivor of the

Alamo.

Her life would come to an end on July 23, 1888,

unknown to mankind as to where she rests today, known only to her

son who buried her at the Rancho de la Laguna Redonda.

The death notice was in the personal journal of Juana’s

son, Alejo E. Perez, and is written in his hand and reads.

Juana

Navarro y Alsbury

The

23rd day of July of 1888, died at 4:30 in the afternoon

at the age of 78 years at the Rancho de la Laguna Redonda where she

is buried. Alejo E.

Perez

We pay honored and tribute to all of the brave men, women,

and children who were in the Alamo and help forged Texas history.

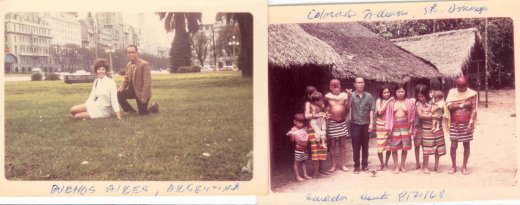

Sometimes

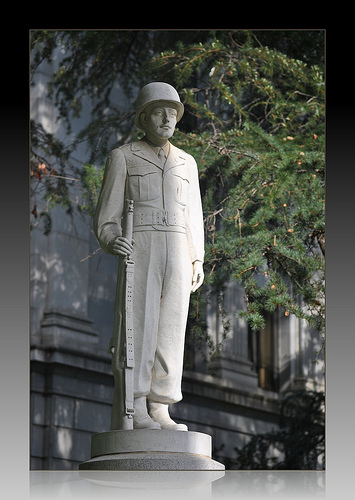

the colossal fruits are piled on the ground, surrounded by

green tropical lushness. Mostly, though, they're displayed

atop baroque stone pedestals. A giant guava in the fertile

jungle becomes the functional equivalent of a heroic warrior

commemorated by a bronze sculpture in an important civic

plaza, or perhaps a religious saint's statue venerated in a

church. Ecuador, then in the late stages of the Spanish

Viceroyalty of Peru that stretched along the Pacific coast,

gobbling up what once had been the powerful Inca empire, is

cast as a prosperous New World Eden.

Sometimes

the colossal fruits are piled on the ground, surrounded by

green tropical lushness. Mostly, though, they're displayed

atop baroque stone pedestals. A giant guava in the fertile

jungle becomes the functional equivalent of a heroic warrior

commemorated by a bronze sculpture in an important civic

plaza, or perhaps a religious saint's statue venerated in a

church. Ecuador, then in the late stages of the Spanish

Viceroyalty of Peru that stretched along the Pacific coast,

gobbling up what once had been the powerful Inca empire, is

cast as a prosperous New World Eden.

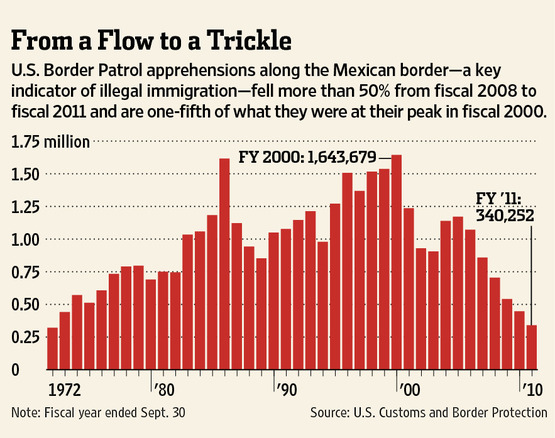

A

U.S. Customs and Border Patrol agent drove along the international

border fence near Nogales, Ariz in September 2010.

A

U.S. Customs and Border Patrol agent drove along the international

border fence near Nogales, Ariz in September 2010.

We

are the #1 site on the

internet for TRUE authentic

quality

We

are the #1 site on the

internet for TRUE authentic

quality

On

the 2012 winter solstice, the earth will be

aligned with the center of the Milky Way for the

first time in 26,000 years. How we interpret this

cosmic event -

On

the 2012 winter solstice, the earth will be

aligned with the center of the Milky Way for the

first time in 26,000 years. How we interpret this

cosmic event -

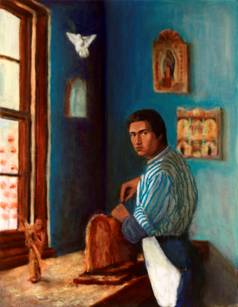

That's

very different from European Baroque paintings, in which

artists cranked up eye-popping illusions of the world as a

theatrical stage for the enactment of salvation. Europeans

needed to combat the barren iconoclasm of the Protestant

Reformation, but that type of pictorial theater didn't

matter in Mexico and Peru, since Protestantism hardly

existed. European Baroque paintings elaborated space, but

colonial Baroque paintings elaborated surfaces.

That's

very different from European Baroque paintings, in which

artists cranked up eye-popping illusions of the world as a

theatrical stage for the enactment of salvation. Europeans

needed to combat the barren iconoclasm of the Protestant

Reformation, but that type of pictorial theater didn't

matter in Mexico and Peru, since Protestantism hardly

existed. European Baroque paintings elaborated space, but

colonial Baroque paintings elaborated surfaces.