he

best way to start this piece is with a caveat that we’re all

writers. Just as we’re all speakers (of whatever language),

we’re all writers (of whatever language)—with the exception of

those who (for whatever reasons) are illiterate (in whatever

language). Sounds like linguistification, but it isn’t. As a

professor of English, I’ve encountered (and continue to encounter)

people who lament the fact that they don’t know how to write. I

assuage them by assuring them that they really know how to

write—that it takes practice and a helping hand. I qvell

when I see the students in my freshman Composition and Rhetoric

classes turning out good writing, especially after they’ve

lamented on the first day that they didn’t know how to write. They

won’t turn out Shakespearean-polished prose at the end of the

first semester in English 101, but with lots of dopamine from me

they turn out essays that communicate sufficiently well their

thoughts, sentiments, and opinions on a variety of topics. So far in

my five years at Western New Mexico University, three students of

mine have been published: one undergraduate from my English 102

class, a graduate student from one of my graduate classes, and three

faculty Ph.D.’s from my Faculty Development Class.

As

for me, my first efforts at writing began at my mother’s knees,

sitting there as she read story after story (in Spanish) to me,

pausing to comment on the illustrations and the letters. Afterwards

she would sit me at the kitchen table and instruct me on how to make

the letters in the book as I copied the stories (in Spanish) on

blank paper. It seems to me that before long I was writing well

enough to make up my own stories with my dog Chata as the main

character.

Chata

was a waif, the runt of her litter, fuzzy-haired with many colors.

She would lay beside me on the floor when I wrote about her. When I

finished a story, I would read it aloud to Chata. Ever watchful, my

mother would hear my stories as I read them to Chata, and sometimes

my mother would poke her head toward me asking me to repeat some

part of the story. That encouragement drove me all the more to

write. I was literate in Spanish by the time I started first grade

in the segregated schools of San Antonio, Texas, in 1932.

Despite

the fact that I struggled with the English language and repeated the

first grade, I kept on writing in Spanish. Our teachers did not seem

to grasp the connection between literacy in Spanish and second

language acquisition. For some time now I’ve characterized that

inability to grasp that connection to the teachers’ belief in the

acoustic theory of language—they believed that the sounds of the

English language wafting through the classroom would reveal their

meanings to the students as soon they reached the students’ ears.

By the 4th grade I still had not gotten the hang of the

English language so I was held back another year. By the time I got

to the 9th grade I was already 2 years older than my

cohort, so I quit school after completing the 9th grade,

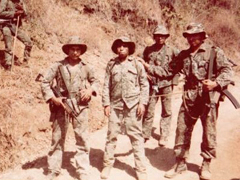

and when I turned 17 joined the Marines that August during the dark

days of 1943 when victory in World War II was far from certain.

In

high school I tried my hand at writing poetry in English. In the

Spring of 1943 my poem “The Gift” was published in Twinings,

the literary magazine of Scott High School in North Braddock,

Pennsylvania, where I was living at the time. After my wartime

service in the Marines I enrolled in 1948 as a provisional student

at the University of Pittsburgh where I took up the study of writing

seriously with the help of Abraham Lauf who got me through Freshman

English.

I

was accepted as a provisional student at Pitt because at War’s

end, Pitt Chancellor Fitzgerald had decreed that any honorably

discharged military member would be welcome at Pitt regardless of

academic background. In the Fall of 1948, the Veterans

Administration placed me at Pitt with only one year of high school.

I signed up for courses in Chemistry, History, Freshman English, and

2 courses in Spanish.

At

the end of the semester I wound up with A’s in the Spanish courses

but F’s in Chemistry, History, and English. My GPA was in the

cellar (1.5). I was advised that in order to enroll in the Spring

1949 semester one of those F’s would have to be a D at least—the

lowest passing grade. The Chemistry and History profs turned me

down. But Abraham Lauf, my Freshman English prof heard me out.

Sympathetically because I was an ex-GI, professor Lauf agreed to

look at my work again, explaining that he wasn’t promising

anything—that if my work merited it he would change the F to a D.

A

couple of days later, Abraham Lauf notified me that he could in good

conscience give me a D for the course. In the Spring semester of

1949 I signed up for professor Lauf’s second semester English

course. I earned a D for the course (let me stress the word

“earned”). I’ve often wondered if this act of kindness on

Professor Lauf’s part influenced my pursuit of the Ph.D. in

English.

Well

into the start of Professor Lauf’s sophomore course on

description and narration, I was despairing of earning anything better

than a “D” on the assignments I was turning in. My papers fairly

dripped of red ink that covered them with his critical remarks and

comments. “He expects us to write like pros,” I thought.

“That’s not fair! He thinks he’s still editor of Redbook

or whatever magazine he worked at before the war. I’ll confront

him.” After all, I had been a Marine Corps sergeant.

He

listened to my complaint, nodded sympathetically (I thought),

then, when I was through, he said matter-of-factly, unintimidated by

my presentation, “Perhaps you should drop the course, Mr. Ortego.”

That was it! He dismissed me with a challenge that not only got my

dander up but also got my “Mexican” determination up.

Needless

to say, I didn’t drop the course. I worked harder. And the harder

I worked, the more red ink poured from Professor Lauf’s pen. About

midway through the course I got the hang of the craft. But that

didn’t stop the red ink. I learned that the better I wrote, the

more he had to say. The more potential he thought you had, the more

he expected from you. And he made us work to the full potential he

thought each of us had.

I

got a “B” from him that semester, and learned the “art of

red ink,” which has characterized my own teaching of writing. I

took three more creative writing courses with Professor Lauf. In the

meantime I did well on the Pitt newspaper and had my first short

story published in the student literary magazine.

More

importantly, however, I learned from Abraham Lauf that when things

get tough one stays the course; and that what is not fair is not

working to the full measure of one’s potential. I’ve often

wondered if Abraham Lauf had not been a Marine Corps sergeant

himself. Perhaps a drill sergeant.

There

were other teachers, of course, who influenced my intellectual and

cognitive development, but “Abe” Lauf is the teacher I

remember best and the one who had the most impact on my life as a

writer. I’m sorry now I didn’t stay in touch with him—and even

sorrier I never told him while he lived how important he was in my

life. I did, however, have an opportunity to honor him with a

memorial essay in A

Celebration of Teachers published by the National Council of

Teachers of English in 1986.

The

University of Pittsburgh nurtured me. It gave me confidence in my

intellectual development and in my skills as a writer. Upon

completion of Advanced ROTC in 1952, at graduation exercises I was

commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the Air Force Reserve.

That summer I worked as an intern at the Pittsburgh

Post-Gazette. In the Fall, the New World Society of Pittsburgh

published a chapbook of my poetry entitled The

Wide Well of Hours, an honor which I have come to consider a success

d’estime which would carry me far as a poet until I found my

voice as an essayist.

fter

Pitt I pursued a career as a teacher and writer, the latter with

astonishing cumulative success, publishing poetry, fiction, and

critical studies as well as placing pieces in national and

international magazines and journals like The Nation, Saturday

Review, The Center Magazine, the Chaucer Review

and The American Scholar, and a host of others. But

there is not one piece I’ve written over the years where Abraham

Lauf has not been looking over my shoulder, nodding, pushing me to

do better.

It

seemed my launch as a writer was a success. But in the following

years I would amass hundreds of rejections, all of which I saved and

are now part of my archive at the Mexican American Archives at the

Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas at Austin,

deposited there in 1986. In the years from 1952 to 1966 I wrote

extensively—mostly poetry. During my active duty years in the Air

Force from 1953 to 1962, scores of my poems were published in The

Stars and Stripes—the military newspaper, some of them

pseudonymously as Marion Van Ives. One particular success of writing

during my years in the Air Force was winning First Place in the

USAFE (U.S. Air Forces Europe) short story competition with the

story “Chicago Blues” judged by Richard Wright and published in Trend

magazine in 1958. The

story would be reprinted a number of times in the ensuing years.

Throughout the rest of the 60’s I wrote poetry furiously, reading

it in whatever venues cropped up—mostly coffee houses of the

time—much of it published here and there in various magazines.

In

the meantime, between 1962 and 1964 I taught French at Jefferson

High School in El Paso, Texas. and in 1964 joined the English

Department at New Mexico State University where I remained until

1970. While at

Jefferson High School I received an award for poetry from the

Trans-Pecos Teachers Association and a poem of mine was included in Odes

of March edited by Bernard Goldberg for the Trans-Pecos Teachers

Association. In 1964

Paso del Norte Press at El Paso, Texas, brought out my second

chapbook of poetry Sangre y

Cenizas—this one in Spanish. At New Mexico State University

from 1964-1970 as Instructor of English I was the first Mexican

American to teach in the English Department.

I

throve at New Mexico State University and in Las Cruces. From 1965

to 1970 I was the Entertainment and Literary Editor of the Las

Cruces Sun News, publishing book, movie, and theater reviews

regularly. In 1967 I won an NEA/Reader’s Digest Foundation Award

for fiction with the story “Soledad,” published in the winter

1968 issue of Puerto del Sol,

literary publication of New Mexico State University at Las Cruces.

That same year I placed my first piece with the Texas

Observer. Also, the Chicano Research Institute of El Paso,

Texas, published my work on

Issues and Challenges in Mexican American Education. Pieces of

mine also appeared at this time in The

New Mexico Review. I was on a publishing streak, placing pieces

with The New England Review, Connecticut Review, Barat Review, The

University Review, The CEA Critic, Books Abroad, Trans-Action,

Choice, CLA Journal, and a host of other publications and

newspapers.

During

this period (1964-1970), I worked with and published a number of

research pieces with Carl L. Rosen who taught me a lot about how to

ascertain the reading problems of Mexican American students. Some of

those works were published by the International

Reading Association, the Journal of Reading Behavior, and by the

U.S. Office of Education (Washington, DC). Fortuitously, during this

time I also worked with and wrote a number of pieces with Mark

Medoff who was then a member of the English Department at New Mexico

State University. Mark would later win a Tony for his play Children

of a Lesser God. Our most significant collaboration was Elsinore,

a musical version of Hamlet,

a play we had high hopes for until Joseph Papp suggested we turn it

into a rock-musical. Perhaps the most memorable moment during the

years from 1964 to 1970 was meeting Octavio Romano, founder of

Quinto Sol Publications at Berkeley, California. Octavio Romano and

I met for the first time in Las Cruces, New Mexico in the summer of

1966, early in my career when I was teaching in the English

department at New Mexico State University and he was visiting Las

Cruces with his wife whose mother lived there.

By

the strangest of circumstances Octavio and I met on campus while

he was looking for the library. We exchanged greetings and paused

to chat. He told me who he was and offered that he was just

strolling the campus. He and his wife were visiting relatives in Las

Cruces. That serendipitous meeting changed my life. I didn’t know

that then, and would not until the end of that decade when I

undertook the study of Backgrounds of Mexican American Literature

at the University of New Mexico (1971), first work in the field.

During

that chance encounter I suggested a cafesito. Octavio and I

talked about sundry academic topics over coffee and pan dulce.

He explained that he was an anthropologist in the School of Public

Health at UC Berkeley, having just received his Ph.D. in 1962. He

also explained that he had worked briefly for the Public Health

Department in Santa Fe.

I

was surprised, for I had never met a Mexican American anthropologist.

I learned that he had received his B.A. at the University of New

Mexico in 1952, the year I left the University of Pittsburgh where I

had majored in comparative studies (languages, literature, and

philosophy) from 1948 to 1952. We swapped war stories. He served

in Europe with the army during World War II. I served in the Pacific

with the Marines.

I

told him about my interests in literature and that I had just

completed a study of Hamlet: The Stamp of One Defect (1966),

an article-length version published in Shakespeare

in the Southwest: Some New Directions edited by T.J. Stafford

and published by Texas Western Press in 1969.

He too was interested in literature, he remarked. So much so

that he and a cohort of Mexican Americans in the Bay Area, including

John Carrillo, Steve Gonzales, Phillip Jimenez, Rebecca Morales,

Ramon Rodriguez, Armando Valdez, and Andres Ybarra, had been thinking

about publishing a literary journal dedicated solely to Mexican

American thought and expression.

That

piqued my interest. He said he’d send me info as the journal

developed. We parted and met irregularly over that summer. Toward

the end of the fall semester of that year, I received a note from

Octavio with details about the journal which would be called El

Grito: Journal of Mexican American Thought and would be

published by Quinto Sol Publications. The symbolism

did not escape me. The term “Chicano” was still percolating on

the ideological stovetops of many Mexican American activists.

Octavio encouraged me to submit work to El Grito. Several of

my pieces were published in that first volume of El Grito. I

thus became one of the Quinto Sol writers. However, what radiated elán

from the Quinto Sol enterprise was the editorial of Volume 1

Number 1 of El Grito in the Fall of 1967: that publication of

El Grito was a manifesto that Mexican Americans would be

judges of their own cultural works; that Mexican Americans would

speak for themselves henceforth, and that all Anglo discourse about

Mexican Americans was suspect and, therefore, would be challenged.

This

discourse, the editorial asserted, “must be stripped of its esoteric

and sanctified verbal garb and have its intellectually spurious

and vicious character exposed to full view.” That has always

struck me as a courageous pronouncement. But the significance of

that editorial lies in its last paragraph: “Only Mexican Americans

themselves can accomplish the collapse of this and other such

rhetorical structures by the exposure of their fallacious nature and

the development of intellectual alternatives.” That was the key:

“intellectual alternatives.”

The

rest is history. El Grito became the premier journal of the

Chicano literary movement, not the only one, but it led the way.

There is no doubt in my mind that without El Grito the

Chicano literary movement would have developed differently–if at

all. Without El Grito there would have been no Premio

Quinto Sol, an award many of us in Chicano literature came to

regard as equivalent to the Nobel Prize or, at least, the Pulitzer.

Who would have published Rudy Anaya’s Bless Me, Ultima?

Or

Rolando Hinojosa’s Estampas

del Valle? Some

other publisher, perhaps, in an alternative dimension or universe.

Octavio

Romano was tapped as the Instructor for The Mexican American

Population 143X, a social analysis course which he described as

overdue (Daily Californian, January 6, 1969). Romano went

on to say that the course would help to offset the John Wayne

syndrome afflicting the American population vis-à-vis Mexican

Americans, closing with the prophetic words: “the Chicano must

realize that he must regain control of his historical function.”

That

was Romano’s consistent theme: Chicanos must define themselves.

This self-definition was the same clarion call I sounded as I prepared

to teach the first course in Mexican American literature at the

University of New Mexico in the fall of 1969. There was a surprising

congruency between Octavio’s political philosophy and mine.

More

importantly, though, Octavio Romano was a pragmatist in the

Greek sense of ideation and accomplishment. That is, for the

Greeks praxis is the ideation of deeds and pragma is

the deed done, actually bringing them to fruition. All too often

in life, there is a disconnect between what we think should be and

its actualization. El Grito (the journal) was actualization

of the need for Chicano self-expression in a time when that need was

paramount and urgent. For me, the consequence of that actualization

was a direction that gave impetus to my life not only in letters but

in Chicano literature. Without Romano’s influence I would probably

have completed a dissertation on Chaucer, which was already in

progress, before I decided to write a dissertation on Mexican

American literature instead, not knowing it would be the first in

the field. That was how profoundly Octavio Romano affected my

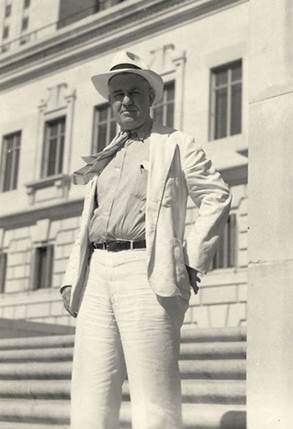

life. Manuel Delgado, a student at Berkeley in 1969, remembers

Romano as a middle-aged guy in wrinkled khaki pants and a white

shirt the day Romano attended a meeting of the Mexican American

Student Confederation, precursor to MEChA on campus. Romano and the

Chicano students were trying to get a Chicano history course

approved at Berkeley for the Spring Quarter of 1969. UC Berkeley was

the last of the California campuses to offer a Chicano studies

course.

My

first efforts as one of the Quinto Sol writers were published

in Volume 1 (1967-1968) of El Grito– “The Coming of

Zamora” (a short story based on the trial of Reies Lopez Tijerina)

and “The Mexican-Dixon Line” (about the Southern plantation

mentality in the Hispanic Southwest). In 1969 Octavio Romano

published El Espejo–The Mirror: Selected Mexican-American

Literature, the first “anthological” salvo of Mexican

American writing in the Chicano era, in ef-fect “the first

anthology of Chicano literature published by Chicanos.”

That

September, I reviewed the anthology for The Nation,

describing it as “a brown paperback book reflecting ‘brown’

literary hopes and aspirations in this country,” adding

that “El Espejo represents the first fruits of a struggling

nascent effort on the part of a nueva ola (new wave) of

literary Mexican Americans.” This review engendered my concept

of “The Chicano Renaissance” which was published in the May 1971

issue of Social Casework. In the fifth printing of El

Espejo (1972), Octavio listed the Quinto Sol writers as part

of the introduction he and Herminio Rios wrote (see Appendix for

List).

In

1971 Octavio Romano published Voices: Readings from El Grito

1967-1971, in which he included my piece on “The Mexican-Dixon

Line.” My academic and literary odyssey led me hither and yon in

the 70’s and distanced my contact with Octavio.

That

distance, however, did not lessen my regard and admiration of him

and his consistent efforts in promoting Chicano literature. Without

Octavio Romano and Quinto Sol Publications and El Grito

would we know about Tomas Rivera, Rudy Anaya, Estela Portillo,

Rolando Hinojosa, Jose Montoya, Alurista, and the host of other

Quinto Sol writers? For me, Octavio Romano was la joya inesperada—the

unexpected jewel, shining in a firmament of jewels that has become

Chicano literature.

y

breakthrough as a writer of public affairs came when Carey

McWilliams (author of North

From Mexico and editor then of The

Nation) assigned me to cover the Cabinet Committee meeting in El

Paso, Texas, in October of 1967, called by President Lyndon Johnson

and moderated by Vice-President Hubert Humphrey.

My piece was entitled “The Minority on the Border: Cabinet

Meeting in El Paso” (The

Nation, December 11, 1967). Other assignments for The

Nation followed. In 1970 my investigative piece on

“Montezuma’s Children” about the deplorable education of

Mexican Americans in the public schools of the Hispanic Southwest

was published as a cover story by The

Center Magazine (November/December 1970) of the John Maynard

Hutchins Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions at Santa

Barbara, California. The piece was read into The

Congressional Record (116 No. 189, November 25, 1970, S 18965)

by Senator Ralph Yarbrough of Texas The piece received the John

Maynard Hutchins citation for distinguished journalism and was

recommended for a Pulitzer.

In

terms of language research, in 1970 the Center for Applied

Linguistics published my monograph on The

Linguistic Imperative in Teaching English to Speakers of Other

Languages, and my piece on “Some Cultural Implications of a

Mexican American Border Dialect of American English was published by

Studies in Linguistics

(October 1970).

The

essence of my work as a scholar and writer was to emerge in 1971

with completion of my Ph.D. dissertation on Backgrounds

of Mexican American Literature, first study in the field. Out of

that work I extracted the essay “The Chicano Renaissance” which

was published in the Journal

of Social Casework (May 1971) as part of a special issue edited

by Celia Aguirre. Later, Margaret Mangold, editor of the Journal

of Social Casework would edit the special issue as a hardcover

book with title La Causa

Chicana: The Movement for Justice.

Part

of the story—perhaps the most important part—in what veered me

toward Chicano literature occurred in 1969 while I was completing my

Ph.D. dissertation as a Teaching Fellow in the English Department at

the University of New Mexico. As director of the newly established

Chicano Studies Program at the University of New Mexico, Louis

Bransford approached me in the Summer of 1969 to organize a course

in Mexican American Literature. I assented readily. That was to be

the most defining moment of my life.

One-hundred

and twenty-two students mostly Indo-Hispanic enrolled for the

course. In my haste—perhaps naiveté—to organize the course I

failed to take into account texts for the students. Setting in

slowly was the reality that there had never been a course like this

taught anywhere. I was plowing new ground. There was a lot of extant

historical material on the shelves of Zimmerman Library at UNM but

almost none of it available in copies for even the smallest number

of students. We made do

with what we could find. Despite the lack of instructional

materials, the course was a success—at least, I thought so.

The

course opened for me a literary aperture I was incognizant of.

Before me was a trove of literature by people like me: Mexican

Americans who had survived the apodictic strictures of making their

way in a country that denigrated them and did not want them, making

their way through a strange political system while being forced to

learn a new language. For me, the course was a portal to a

consciousness I had not dreamed possible. Yes that consciousness had

nibbled at the edges of awareness but it was the course that nudged

me toward the light. At the beginning of the Spring semester of

1970, I met with Joe Zavadil, Chair of the English Department at UNM,

explaining my request to change my dissertation topic to one on

Mexican American Literature. He was surprised for I had already

completed three chapters of a dissertation on Chaucer. Edith

Buchanan was my advisor. Joe Zavadil acceded with the proviso,

however, that I had to find three faculty members to work with me.

There were, of course none who had worked in this field. But I

persuaded David Remley, Robert Fleming, and David Johnson to be my

dissertation committee. We were four sailors on a ship without a

rudder; I was in the crow’s nest. I would look for the material;

they would help me with the format.

The

arrangement worked out well. I delayed Ph.D. graduation by 15

months, receiving the Ph.D. in English in August of 1971. Later I

would learn that my dissertation was the first in the field, and

that I was the first Mexican American to receive the Ph.D. in

English at the University of New Mexico. I would also learn that I

was the 5th Mexican American in the country with the

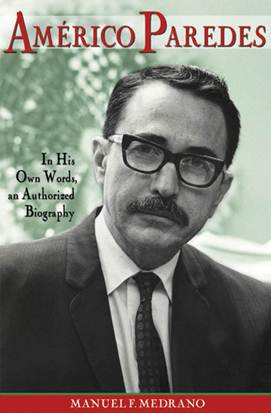

Ph.D. in English: the 1st was Americo Paredes, 1956; 2nd

Carlos Ramos, 1965; 3rd Robert Padilla, 1968; 4th

Arturo Islas, May 1971; 5th Felipe Ortego, August 1971.

he

decade of the 70’s would be a momentous decade for me, starting

with completion of my dissertation Backgrounds

of Mexican American Literature. In February of 1970, Ray Small,

Dean of Arts and Sciences at the University of Texas at El Paso

inquired if I’d be interested in applying for a teaching position

in English with additional duties in organizing a Chicano Studies

Program. Loathe as I was to leave New Mexico State University after

6 years there, I said “yes.”

In

April of 1970, Ray Small informed me I was a finalist for the

position he had described, and invited me to UT El Paso for an

interview. What an interview that was! The faculty of the English

department greeted me warmly. I did, after all, know most of them. I

was not prepared for the grueling interview by the MEChA students.

Mistakenly—or perhaps pompously—I assumed that my growing

reputation as a writer and scholar in Chicano literature would carry

the day for me. I was not only publishing well on the English and

American canon of writers (Chaucer, Shakespeare, Johnson, Browning,

Melville, Steinbeck, and other literary luminaries), but publishing

well in Chicano literature and public affairs.

My

interview with the MEChA students was like my interrogations of

Strategic Air Command pilots at the Air Force Survival School in the

isolated high desert of Reno, Nevada, during my nine years in the

Air Force. The MEChA students were determined to peel away any

layers of inauthenticity in their search for the real Felipe Ortego.

Having been a World War II Marine in the Pacific, I was not

intimidated by the students. In fact, my admiration for them grew

larger as they pressed on with the interview. They got to the

ideological nub of my commitment to the Chicano Movement. Satisfied,

they settled on me. To this day, I don’t know who the other

finalists were. But the confidence of the MEChA students in choosing

me to be founding director of Chicano Studies at UT El Paso changed

my life.

I

settled in as Founding Director of Chicano Studies at UT El Paso on

August 15, 1970, and began immediately on the proposal to the UT

Board of Regents and the Texas Commission on Higher Education to

establish the Chicano Studies Program at UTEP. Helping me were MEChA

students and Mario and Richard Garcia both of whom had finished

their graduate work at UTEP and bound for Ph.D.’s elsewhere. With

my appointment in the English Department and that of Santiago

Rodriguez in social Work, the Chicano faculty at UT El Paso doubled.

On board already were Norma Hernandez in Education and Jesus

Provencio in Mathematics. There were other Hispanic faculty on

campus who were not Chicanos, that is, Mexican Americans. Of the

Chicanos we were four in number, not counting Pete Duarte who was a

graduate student in Sociology. The Chicano Studies Program was

housed in Graham Hall, second floor. My appointment was jointly in

English and Chicano Studies.

What

I noticed most about UT in 1970 was the presence of so many

mejicanos, all of them sweeping floors, cleaning windows, mowing

lawns, trimming trees, dusting furniture in offices, vacuuming

carpets, and serving food in the cafeteria. We were everywhere

except in the classrooms as faculty and as administrators at any

level of the university hierarchy. Bear in mind that in 1970 the

mejicano population of El Paso was well over 70% while almost half

the student body at UT El Paso were mejicanos. Those figures are

dramatically higher today.

In

shaping the Chicano Studies Program at UT El Paso, our bible was El

Plan de Santa Barbara, the Chicano Studies template forged at UC

Santa Barbara in 1969 by the Chicano Coordinating Council on Higher

Education “as a manifesto for the implementation of Chicano

Studies,” not only in

California but everywhere. The most compelling aspect of El

Plan de Santa Barbara was the role of community participation in

Chicano Studies. Uppermost in our minds was the mantra that: A

Chicano Studies Program without Chicano control is not a Chicano

Studies Program. At UT El Paso we quickly organized a Mesa

Directiva to bring the Chicano community into the academic

sphere. The most prominent members of la

Mesa Directiva were Jose Piñon, a pharmacist and Hector Bencomo,

a grocer and El Paso Councilman. Both were to play key roles in the

MEChA takeover of the administration building in December of 1971.

While

the Chicano Studies proposal formally established the Chicano

Studies Program at UT El Paso, the principal impetus for the

formation of Chicano Studies on campus came from the MEChA students

roiled into action by the string of high school walkouts during

1969, among them the student walkouts at Bowie High School and at

Jefferson High School. Chicano

activism was not exclusively a California phenomenon, though the

first Chicano Studies program in the country was established at

California State University—Los Angeles in 1968, followed by

formation of the Chicano Studies Department at California State

University—Northridge in 1969. In 1970 the first Chicano Studies

Program in Texas was established at the University of Texas at El

Paso, third in the nation, although UT Austin has contested that

claim. Celos! Puros celos!

There

were many considerations to take into account in getting Chicano

Studies up and running at UT El Paso, first among them an academic

structure consonant with the philosophy and objectives of Chicano

Studies. We all knew what was needed and where we wanted to go. The

question was: How to get there? And, of course, how to decide? The

first steps were obvious. We organized a Chicano caucus of students,

faculty, and community supporters. The proposal for the Chicano

Studies program came out of this caucus. Needless to say there were

hurdles in the deliberations of the caucus, deliberations which gave

credence to the proposition that when you get three Chicanos to

deliberate you get four opinions. But I jest!

Being

focused and single-minded, and thanks to students of MEChA, the

caucus achieved not just consensus but unanimity. By November we

received word that the Chicano Studies proposal had been approved.

Anticipating that approval, we hired Ana Osante—may she rest in

peace—as the Chicano Studies secretary who came to embody the

spirit of Chicano Studies. With so much preliminary work to conduct,

we hired student workers as well—two of whom were Patricia Roybal

and Hilda Parra.

There

were administrators and faculty members who wanted us to succeed;

and there were those who wanted to see us fail, that is, those who

regarded Chicano Studies as a divisive academic wedge. In part, that

perspective nudged us toward crafting Chicano Studies as an

interdisciplinary program and as a strategy for providing staffing

by the departments: that way we would have courses and a cudgel in

getting Chicano faculty in the departments.

Increasing

the presence of Chicano faculty on campus would prove to be our

donnybrook. The stumbling block there was garnering faculty support

in the departments to hire Chicano faculty. In this regard, our

strongest faculty supporters then were John Haddox, professor of

Philosophy, Melvin Strauss, professor of Political Science, and Ray

Small, Dean of Arts and Sciences. There were others, of course; not

many, but others. I always thought President Smiley was in our camp

but caught in a web of disdain and malice wrought by the powers in

the UT system who saw us as Meskins, pretty much the way the Texas

Rangers and Walter Prescott Webb saw us. In the end, Joe Smiley and

I were collateral victims in the ideological struggle for Chicano

representation at UT El Paso.

Many

of us in the Chicano caucus thought that the interdisciplinary

approach was preferable since it seemed to be a way of increasing

our numbers throughout the academic departments rather then

clustering them in one department. At Western New Mexico University

we have a Department of Chicana/Chicano and Hemispheric Studies with

affiliate faculty in the various academic departments of the

university, a hybrid version of a departmental and interdisciplinary

structure which seems to be working well for us. We have the

autonomy of a department while at the same time influence in the

departments via Hispanic/Latino faculty.

No matter the structure, the interdisciplinary program of Chicano

Studies at UT El Paso has survived 40 years. That’s a testament to

its foundation and its stewardship.

But its history has not been without travail. In recruiting

Chicano professors for the various disciplines, we were met with

departmental disdain and intransigence engendered by institutional

disdain. No departments were taking us seriously. That’s what

ignited the MEChA takeover of the Administration Building and

holding the president hostage for 36 hours on that December day of

1971. We were all frustrated; the students moreso. Our efforts at

galvanizing the mejicano community to support us were met with consejos

to tone down the rhetoric, to slow down, we were going too fast,

expecting too much, too soon. In the spring of that year when Tony

Bonilla, Texas Director of LULAC and I and a contingent of mejicanos

(including students) from El Paso met with Texas Governor Preston

Smith beseeching him to appoint mejicanos to Texas universities’

boards of regents, he had his Sergeant-at-Arms throw us out of his

office, admonishing us that as Governor he could not favor one group

over another. That was the climate in Texas at that time.

That

fatiric morning of the takeover I was caught by surprise. Not that

the students didn’t trust me; they were protecting me but I

perished anyway. After a morning of wrangling with President Smiley,

we were no further ahead than when we started.

None of us could persuade the president to consider our

“demands”—perhaps “non-negotiable demands” was a poor

choice of words. Then silently as the clock moved toward noon, the

MEChA students ushered the secretaries out of the office and locked

the doors. Phones were disabled. Joe Smiley grew nervous. The room

crackled with the electricity of uncertainty. I felt like an actor

in a play with an unfamiliar script, improvising the next scene,

ad-libbing the lines. Outside, as if anticipating the takeover,

Chicano students began to flock around the administration building.

Newspaper estimates described the throng as 3500 strong, but Agapito

Mendoza, who went on to become Vice Provost at the University of

Missouri at Kansas City, asserts that 5,000 Chicano students)

encircled the administration building keeping out the police and

other authorities, chanting paeans of liberation. Other students

were letting the air out of the tires of police cars and buses,

alert to police snipers on the roofs of nearby buildings, alert to

the aggregation of sheriffs’ posses and military troops from

nearby Fort Bliss. On that autumn day of December 1971, Chicano

students at UT El Paso had stormed their Bastille and were at

one with other student liberators around the globe.

I

was not the leader of the group, but as its most elder I wheedled,

I pleaded, I sought to get Joseph Smiley to see the justice of our

cause. Nothing seemed to work but, finally, the impasse broke and

we reached a settlement with the president. Via his office, he

would support stronger recruitment of Chicano faculty, more

departmental collegiality with Chicano Studies, a stronger institutional

affirmative action plan to improve opportunities for Chicano staff

within the university infrastructure. We were victorious—but at

what cost?

The

students and I were rounded up and carted off to jail, charged with

felonies. Thanks to the efforts of Hector Bencomo, Jose Piñon,

Jesus Ochoa, Tati Santiestaban, and Paul Moreno we were not

charged—branded, yes, but not charged. The university would not

press charges against us, though the event had serious criminal

consequences. I was regarded as the instigator—my contract was not

renewed for the 1972-73 academic year. Pero

como dice el dicho: no hay mal que por bien no venga—even an ill

wind blows some good.

The

takeover was not in vain. The MEChA students had served notice on

the university—nay, to Texas—that the “good ol’ boy” way

of doing business with mejicanos was headed for the scrap-heap of

history. We made great strides the following semester. By the time I

left UT El Paso in May of 1972, the Chicano faculty included Tomas

Arciniega in Education, Rudolfo de la Garza in Political Science,

Donald Castro in English, Hector Serrano in Drama, Rudy Gomez in

History, and Karen Ramirez in Linguistics. There were others. In

retrospect, nos despedimos

(we left) with heads held high. Pero

la lucha continuó y contínua! But the struggle still continues!

Joe

Smiley was forced into retirement for giving in to the demands of

the MEChA students. But the acrimony that event engendered from the

Anglo professoriate at UTEP, the Anglo students on campus, and the

Anglo community of El Paso, persisted for many years after. Some

professors stopped talking to me; others became hostile; some

branded me as a “communist.“ Some of that acrimony persists to

this day, fueled by the fiery vestiges of “the Black

Legend”—the stereotypes that have plagued Spaniards and their

progeny everywhere since the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Years

later, Joe Olvera wrote to me saying: “Thank you, Dr. Ortego.

I’ll never forget how you stood with us when we took over the

Administration Building at UTEP in 1971 and held the President

hostage. Your courage under fire was admirable. You placed your

career on the line and never flinched. But of course you had been a

Marine during World War II. No wonder your bravery was so

uncompromising.”

Two

successes occurred over that summer of 1972: the first phase of the

Task “Force on Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English (of

which I was a founding member) actuated by the National Council of

Teachers of English in cooperation with the College Conference on

Composition and Communication had come to a close with publication

of Searching for America,

edited by Ernece Kelly. In Searching for America, the Task Force

made up of the Chicano Caucus (of which I was Chair), the African

American Caucus (chaired by Ernece Kelly), the Native American

Caucus (chaired by Montana Rickards), and the Asian American Caucus

(chaired by Jeffrey Chan) surveyed the anthologies of American

literature used in Colleges and Universities for inclusion of

minority American writers. Needless to say, the inclusion of

minority writers was nominal, including only a couple of African

American writers. There were no Chicano, Native American, nor Asian

American writers included in those anthologies. In fact, the paucity

of women writers astounded us. Searching

for America was a stinging criticism of American publishers and

their neglect of minority American writers. Searching

for America includes my piece on “Chicanos and American

Literature’ (with Jose Carrasco), reprinted by Wiley and Sons in The

Wiley Reader: Designs for Writing in 1976.

In

the Summer of 1972 I was asked to edit a special issue of Educational

Resources and Techniques focusing on Chicano Literature. The

issue turned out quite well garnering kudos from a variety of

sources.

he

year 1972 was both calamitous and rewarding. The calamity was that

my contract at the University of Texas at El Paso was not renewed;

the year was rewarding because no

hay mal que por bien no venga—even an ill wind blows some

good.

Unexpectedly,

through a mutual friend in Denver, Colorado, James Palmer, president

at Metropolitan State College in Denver called me to ask if I’d be

interested in being his assistant. I had not despaired in finding a

new post. In fact I interviewed for a position at Stanford, Cal

State-San Luis Obispo, and at UC Santa Barbara. After James

Palmer’s call, the Metro State post appealed the most to me.

I

moved to Denver to be Assistant to the President at Metro State

College where I met Dan Valdes and became one of the founders of La

Luz magazine, first national Hispanic public affairs magazine in

English. In 1973, thanks to James Palmer, I went off to Columbia

University for post-doctoral studies in Management and Planning for

Higher Education which helped me in 1974 as one of the founders of

the Hispanic University of America, first major effort to establish

a stand-alone university for American Hispanos by American Hispanos,

and was named Vice-Chancellor for Academic Development. That year I

was also the prime candidate for the presidency at Texas A&I

University at Kingsville. Rejected, I filed an EEOC (Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission) suit against the university which

was not settled until 1982 in my favor.

My

story was that I left UT El Paso in 1972 to pursue better

opportunities elsewhere, but Dan Valdes knew the real story since he

was the one who recommended me to Jim Palmer who told me he knew

what happened at UT El Paso, and from what Dan Valdes told him about

me, I was the “man” for the job. By August I moved all my stuff

from El Paso to Denver. In fact, I made that move with Santiago

Rodriguez, who we to Denver to work on the DSW (Doctor of Social

Work) at the University of Denver. Coincidently we both started at

UT El Paso at the same time in 1970. Our arrival that year at UT El

Paso doubled the size of the Chicano faculty. In Denver, Santiago

and I found a modest but comfortable apartment near the downtown

area, not far from the Brown Palace. The following spring I found an

apartment nearer to Metro State College. Santiago moved closer to

the University of Denver further out on the west side.

On

my arrival at Metro State Dan Valdes greeted me warmly, showed me

around the Metro campus which was really not a campus at all. The

college rented all its space in a cluster of buildings near

downtown. Later, it would become part of the Auraria Complex of

colleges which would occupy the Auraria site just off Cherry Creek

downtown. The arrangement of three institutions of higher learning

on one campus—Metro State, Auraria Community College, and the

University of Colorado Denver Center—reminded me of the Air Force

arrangements of a Base with a Commander who provided support

services for tenant units that had their own commanders.

When

I arrived at Metro State in August of 1972 that arrangement was

still in the future. I was impressed by the truly urban character

of the college, taking classes out to the community. I had come from

one grand enterprise in Chicano education to an equally grand

enterprise in urban education. In addition to being Jim Palmer’s

executive assistant, I was also Associate Professor of Urban Studies–one

foot in administration and the other foot planted firmly in the

ranks of the faculty where I was “home.”

Working

with Dan Valdes on La Luz

was a boon in my publishing experience. Dan Valdes who later, after

we met, styled himself as “Dan Valdes y Tapia”–was a product

of the San Luis Valley of Southern Colorado; and proud of his

Hispanic roots which stretched back to the earliest settlements of

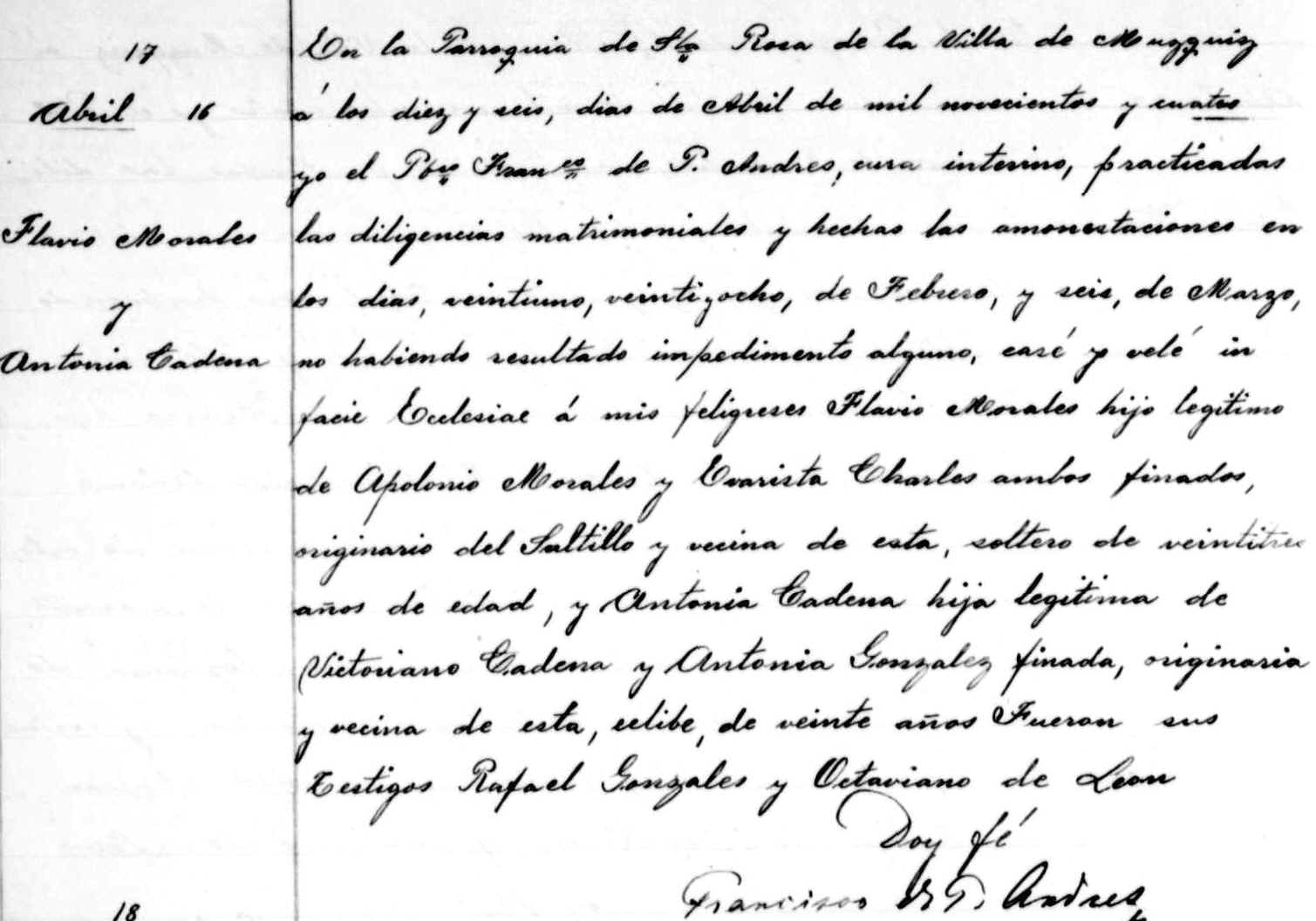

the Spaniards in North America. Through an agency of a branch of my

mother’s family, my roots in Texas stretch back to 1731, to the 16

families that founded the city of San Antonio, Texas.

At

Metro, Dan Valdes took me under his wing and immediately included me

in his circle of entrepreneurs who were involved in establishing La

Luz Magazine, first national Hispanic public affairs magazine in

English. Not long thereafter I became Managing Editor of the

magazine and Associate Publisher. Within a short time I was the

second largest holder of stock in the magazine. Dan held control of

the magazine with 51 percent of the stock.

Dan

Valdes was cantankerous and he disliked banks. I never knew where he

stashed his money, and he almost never carried money with him.

Invariably I wound up paying for our morning coffee at Dunkin Donuts

located conveniently around the corner from the offices of La

Luz in Glendale. But Dan was generous with me. He didn’t

approve of the term “Chicano” but he gave me the space to call

myself a Chicano. My first title with La Luz was as Literary Editor

which gave me considerable leeway with topics. More importantly,

however, there was chemistry between Dan and me that sparked

inspiration in my association with him and La

Luz.

That

first year cost La Luz a million dollars to operate. Fortunately,

the magazine managed to attract enough income to allay the expenses.

To cut operating costs after that first year the magazine was

reduced in size from “Life” size to “Time” size. At the helm

of the editorial tiller of the magazine, I sought to make it a

publication that truly reflected the diversity of Hispanics in the

United States while maintaining its cultural identity with the

Hispanics of the Southwest principally Mexican Americans and

Chicanos. By 1975 the readership of La Luz magazine—which we

touted as the first Hispanic public affairs magazine in

English—had grown to 500,000.

In

many ways, La Luz magazine was ahead of the Hispanic curve in the

United States. Which is why we had trouble attracting mainstream

advertisers. Our subscription rates were low. Any income from

subscriptions quickly went for production, leaving us with the

liability of subscribers who had already paid for the magazine. We

scrambled for every penny to keep the magazine afloat.

In

terms of content we published established Hispanic writers and

newcomers. One of the earliest Hispanic personalities to be

published in La Luz was Juan Bruce Novoa. Juan was 28 when I first

met him in the fall of 1972 in Denver, Colorado; I was 46. Though a

generation separated Juan Bruce-Novoa and me, we were peers and

colleagues in the roiling pot of Chicano literature. That September

of 1972, Juan and I gave presentations in Denver at the joint

conference of the

Colorado Council of Hispanic Educators and the American Association

of Publishers. In an open letter to me published in La

Luz Magazine in 1973, Juan wrote:

I

sat listening to you deliver the keynote address . . . . you seemed

to be in your usual top form. You proceeded to reprimand the

publishers for their lack of minority authors in their catalogues

and briefly recounted the various paths that minorities, especially

Mexican Americans, had taken in the past and the new developments n

the present scene. During the speech, you called for a new

aesthetic, one not biased in favor of the Anglo writer, one that

would allow the Chicano contributions to American culture to take

their rightful place along side those of other groups. A new

literary aesthetic, a Chicano aesthetic, by which to judge the works

of the Chicano author.

In

that presentation, my call for a Chicano aesthetic was to free

Chicano literature from the burdens of history and the shackles of

American literature. In that Open Letter, Juan Bruce-Novoa

proceeded:

Later

in the conference, I rose to address the two groups myself. I also

called for a new aesthetic, artistic as well as critical. I deplored

as I always have, the existence of any pre-established definitions

of the characteristics of art and its sub-types. Those that have

been proffered by segments of the Chicano movement are no less

oppressive than those so long held by the anglo critics. I called

for complete freedom to write about anything, in any way and in any

language without cultural, regional or political prerequisites. No

restrictions from outside nor inside the Movement. To compliment

this freedom, a new critical approach: post analysis instead of

prejudgment.

Juan Bruce-Novoa

Freedom of Expression and the Chicano Movement:

An Open Letter to Dr. Philip Ortego

To

my knowledge, this was the first published piece by Juan Bruce-Novoa.

This would be the first in a string of exchanges we would have over

the next 28 years. Over each of those years our perspectives on

Chicano literature would be sharpened and refined. While we were not

in absolute agreement in everything about Chicano literature there

was certainly no contradiction between my call for a Chicano

cultural aesthetic and Juan’s call for an acultural one. We were

both concerned about the rise of norms that could stifle Chicano

literature aborning.

In

Denver, Juan and I would meet often for charlas

on Chicano literature over cafesitos

here and there in the many coffee shops scattered across the

city at the time. In August of 1973, I went off to San Jose State

University as a visiting professor in English, Chicano Studies, and

Social Work. Juan graciously hosted a bon

voyage gathering at his house for me at which he presented me

with a framed copy of one of his etchings entitled “Innocencia

Perversa” which would be the title of his book of poetry

published in 1977. The work has always hung prominently wherever

I’ve lived—still does.

I

should add that in the Spring of 1973 I applied for the presidency

at Texas A&I University in Kingsville, Texas. Having worked with

James Palmer as his Executive Assistant, I felt ready for a

presidency. It turned out I had lots of community support for my

candidacy. I surfaced as the first choice of the selection

committee. Following historical protocol, the regents should have

offered me the post. Unfortunately, the Regents of the University

chose the number three person on the list of recommended candidates.

It turned out that they fired their choice within three years for

incompetency. I’ve since joked that they should have given me the

chance to be as incompetent as he was. I filed an EEOC suit against

the University. The case was not adjudicated until 1982 with the

EEOC finding in my favor. The University settled with me though I

would have preferred the job. Pos, asi es la vida!

Returning

to Denver after my visiting stint at San Jose where I became a fast

friend of Ernesto Galarza, I threw myself into La

Luz Magazine as its Managing Editor, hawking the magazine hither

and yon. Juan went off to Yale and finished his dissertation. In

January of 1974, Juan invited me to Yale for a Roundtable

presentation on Chicano literature which I entitled “The Forgotten

Pages of American Literature.” Tino Villanueva and Carlos Morton

presented at the Roundtable also, the proceedings of which were

published in the Journal of

Ethnic Studies (Spring, 1975).

It

was bitterly cold in New Haven that January, ice-storms almost

paralyzed the area. I flew into New York from Denver and went on to

New Haven by bus. As always, Juan was the perfect host (in a smoking

jacket no less). Wine warmed us and words stirred us to passion. The

rhetoric of Aztlan pushed us onward and upward—arriba y adelante!

At that conference, Juan introduced me to Paul de Man, the

controversial proponent of deconstruction,

who sympathized with the plight of Chicano literature.

That

cold and icy winter reminded me of the days of my youth in Chicago

(1936-1940) with winters no less cold or icy. Though brief, my visit

to Yale and New Haven also stirred in me memories of my winters from

1948 to 1952 in Pittsburgh where I was an undergraduate student at

the University of Pittsburgh majoring in comparative studies

(languages, literature and philosophy). Now here I was at 48 in the

northern reaches of Aztlan preaching the gospel of Aztlan to the

uninformed. But Juan was doing a great job there by himself, drawing

Chicano students from Aztlan to the gothic chambers of Yale. Two

years earlier I had lectured at Harvard on Chicano literature,

recording that experience and my visit to Cape Cod in a piece

entitled “Lest Darkness Overtake Me.” There I was, an Argonaut

from Texas looking for my immortal soul on that stark stretch of

rocks jutting out into the Atlantic from Provincetown.

In

October of 1974, David Conde and I organized the first National

Chicano Literary Conference at Highlands University in Las Vegas,

New Mexico. Chicanos from across the nation came. Juan Bruce-Novoa

came and delivered a blockbuster of literary theory which he called

“The Space of Chicano Literature.” Twenty years later at a

Chicano literary conference at the University of Mexico in Mexico

City which Juan and I both attended, I confessed (jocularly) that

for all the years since his presentation of “The Space of Chicano

Literature” I pretended

to understand the concept of Juan’s theory for fear of being found

out that I didn’t.

Juan’s

concept of the space of Chicano literature was an important step in

the advancement of Chicano literature and critical theory. Thanks to

Henry Casso, the Proceedings of that conference were published as The

Chicano Literary World—1974 by the National Education Task

Force de la Raza in 1975 and republished by Jose Armas as a special

issue of

De Colores (1:4, 1975) of Pajarito Press.

Juan was the man of the hour at that conference. Thirty years

later in 2004, Juan and I would reunite at New Mexico Highlands

University for the 30th commemorative anniversary of that

conference. We were both considerably grayer by that time, though

now I was walking with a cane. Juan looked as trim and young as

always.

In

November of 1974, Juan and I were at another conference on Chicano

literature at the University of Texas at Austin when we heard that

the Fort Worth Independent School District had banned all Chicano

books and materials from their schools. On the banned books list was

We Are Chicanos: Anthology of

Mexican American Literature which I had edited for Washington

Square Press in 1973. Thanks

to all our efforts but especially Juan’s, we were able to exert

enough pressure on the Fort Worth Independent School District to

rescind its ban. The reason for the ban—the Chicano books incited

revolt and revolution. Shades of the Texas Textbook Massacre of 2010

by the Texas State Board of Education.

Over

the following decades, Juan traveled extensively, principally in

Europe, curtailing our encounters. On occasion, however, I‘d

receive a note or missive from him posted from Germany or Spain or

wherever his travels had taken him. In those years I thought of him

as a bon vivant. But he

was always the critical observer of the human condition. Our

disagreements were always jovial, although I bristled a bit when he

referred to me once as a “media mogul” in one of his works. In

2005 I received a congratulatory note from Juan for receiving the Patricia

and Rudolfo Anaya Critica Nueva Award from the University of New

Mexico for “scholarly achievement and exemplary contributions to

Chicana-Chicano literature.”

The

last time I saw Juan was on April 24th of 2007 at the 13th

Annual Multicultural Conference in San Antonio, Texas, hosted by San

Antonio College and Juanita Lawhn. At that conference I received the

Premio Letras de Aztlan

from the National Association of Chicana and Chicano Studies—Tejas

Foco “for lifetime work and achievement in Chicana/o scholarship

and community activism.” I gave the keynote presentation and Juan

introduced me, explaining in that introduction “On

Renaissance, Luz, and Selective Amnesia: An Overdue

Tribute to Felipe Ortego" his

perception of my role in the birthing of Chicano literature and the

days of our friendship when I was with La

Luz Magazine in Denver. His words brought tears to my eyes. I

had no idea that would be the last time I would see Juan Bruce-Novoa.

Like Lycidas in John Milton’s pastoral elegy, Juan was too young

to die.

Other

stellar Hispanic writers whom we featured in La Luz were Rosario

Castellanos, Ricardo Sanchez, and Ernesto Galarza, to name but a

few. I wrote monthly editorials with a column heading of “Mano a

Mano.” We covered the waterfront for news of Hispanic events in

the United States. In retrospect, we were so far out on the leading

edge of change in publishing the U.S. Hispanic/Latino experience

that we sank by the sheer weight of innovation and mainstream

ignorance of who Hispanics were and their significance to the

American market and culture

One

of Dan Valdes’ dreams was to establish a stand-alone university

dedicated to the education of American Hispanics much like Howard

University in Washington, DC is dedicated to the education of

African Americans. That dream emerged in 1973 when Dan convened a

group of prominent educators attracted by Dan’s vision for the

Hispanic University of America. Among them was James Palmer,

President at Metropolitan State College in Denver for whom at the

time I was his Executive Vice President. In the plan for the

Hispanic University of America, Dan was Chancellor and I was Vice

Chancellor for Academic Development. By 1974 the Hispanic University

of America had a campus thanks to the Catholic Diocese of Denver who

gave us tenancy at one of the Catholic campuses in the area. We had

lots of enthusiasm but little money. Dan was able to catch the

attention of U.S. Senator Joe Montoya from New Mexico to take up our

cause in Congress by promoting a bill for the development of

Hispanic colleges and universities much like the Historically Black

Colleges and Universities (HBCU). The going for that bill was tough

but just when it seemed that success loomed Senator Montoya was

defeated by Republican astronaut Harrison Schmitt in 1977. Our

chances for securing funding for the Hispanic University of America

dissipated. For a brief time we operated like a university, classes

and all. As Vice Chancellor for Academic Development I developed the

academic curriculum for the university My faculty appointment with

the university was as Professor of Hispanic Studies and Research.

Owing

to financial exigencies during which I taught at Angelo State

University in San Angelo, Texas, in 1978 I accepted a post at Our

Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, Texas, as Founding

Director of the Institute for Intercultural Studies and Research. By

1980 Dan Valdes threw in the towel with the Hispanic University of

America. I continued with La Luz magazine from a distance. In 1980

Dan and his long-time girlfriend Maria married in San Antonio,

Texas. I was his best man. Dan died suddenly in 1982. He was 72.

When

Dan Valdes died my enthusiasm for La

Luz magazine ebbed, and I sold my shares of La

Luz stock. Dan Valdes was a true pioneer in promoting the story

of American Hispanics. There were others before him, of course, who

had sought to tell that story, but following Robert

Browning’s injunction that a man’s reach ought to exceed

his grasp, Dan Valdes reached well beyond his grasp to the moons of

Barzoom in promoting the presence of Hispanics in the United States.

Dan’s death closed a significant chapter in my life.

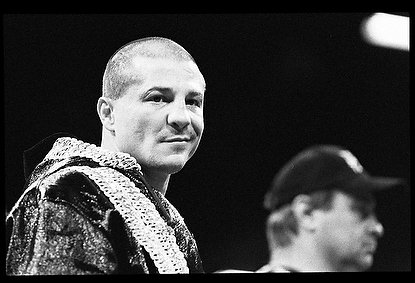

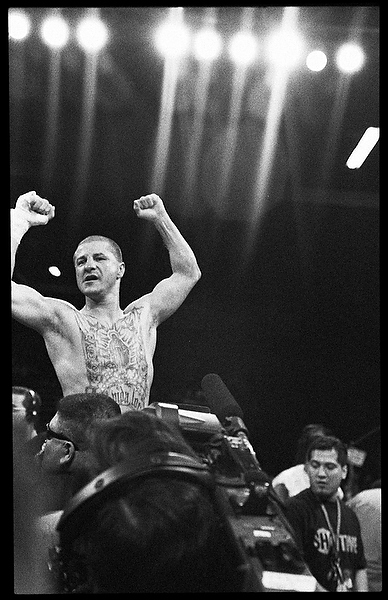

Destined

for the Boxing Hall of Fame, Tapia has fought 12 world champions

during his career, losing only to Barrera and Ayala. Though Foster was

the only undisputed world champ to come out of New Mexico, and the

only lineal champ (i.e. “the man who beat the man who beat the man .

. . .”), Tapia’s titles were in four weight divisions, from 112 to

126, while Foster reigned only at light-heavy.

Destined

for the Boxing Hall of Fame, Tapia has fought 12 world champions

during his career, losing only to Barrera and Ayala. Though Foster was

the only undisputed world champ to come out of New Mexico, and the

only lineal champ (i.e. “the man who beat the man who beat the man .

. . .”), Tapia’s titles were in four weight divisions, from 112 to

126, while Foster reigned only at light-heavy.

ADF

attorney Jordan Lorence: "Americans in the marketplace should not

be subjected to legal attacks for simply abiding by their beliefs.

Should the government force a videographer who is an animal rights

activist to create a video promoting hunting and taxidermy? Of course

not -- and neither should the government force this photographer to

promote a message that violates her conscience."

Lorence goes on to say that because the constitution prohibits the

state from forcing unwilling artists to promote a message they

disagree with, ADF will appeal the decision to the New Mexico Supreme

Court.

ADF

attorney Jordan Lorence: "Americans in the marketplace should not

be subjected to legal attacks for simply abiding by their beliefs.

Should the government force a videographer who is an animal rights

activist to create a video promoting hunting and taxidermy? Of course

not -- and neither should the government force this photographer to

promote a message that violates her conscience."

Lorence goes on to say that because the constitution prohibits the

state from forcing unwilling artists to promote a message they

disagree with, ADF will appeal the decision to the New Mexico Supreme

Court.

A

Judeo-Christian law firm that fights for faith and freedom plans to

appeal a federal judge's decision to dismiss its constitutional

challenge to the U.S. government's bailout of the American

International Group (AIG).

A

Judeo-Christian law firm that fights for faith and freedom plans to

appeal a federal judge's decision to dismiss its constitutional

challenge to the U.S. government's bailout of the American

International Group (AIG). "Certainly

we know that if the federal government even gave a fraction of that

amount of money to a Christian or a Jewish religious activity, there's

no doubt in my mind the courts would strike that down and find it a

violation of the Establishment Clause," Muise offers. "But

yet here we've got billions of dollars going to support activities

that are promoting sharia law, Islamic law, and yet we have the Sixth

Circuit, at least one panel, saying that there isn't any

constitutional harm here sufficient to have standing."

"Certainly

we know that if the federal government even gave a fraction of that

amount of money to a Christian or a Jewish religious activity, there's

no doubt in my mind the courts would strike that down and find it a

violation of the Establishment Clause," Muise offers. "But

yet here we've got billions of dollars going to support activities

that are promoting sharia law, Islamic law, and yet we have the Sixth

Circuit, at least one panel, saying that there isn't any

constitutional harm here sufficient to have standing."

These

dedicated teachers withstood the inequities of segregated schools and

earned the love and respect of their African American students and

their families. They remained active in their teachers' union and

garnered the respect of their colleagues. When desegregation occurred,

they were caught up in a process of change and discrimination which

could have resulted in their teaching careers ending in Globe and

Miami. Through their own persistence and with assistance from the AEA,

they were able to continue to work in their chosen profession.

These

dedicated teachers withstood the inequities of segregated schools and

earned the love and respect of their African American students and

their families. They remained active in their teachers' union and

garnered the respect of their colleagues. When desegregation occurred,

they were caught up in a process of change and discrimination which

could have resulted in their teaching careers ending in Globe and

Miami. Through their own persistence and with assistance from the AEA,

they were able to continue to work in their chosen profession.

At

the NAHP Convention October 18-20, 2012 in San Diego awards will be

presented to publishers, journalists, editors, art directors &

marketing professionals. The National Association of Hispanic

Publications' José Martí Publishing Awards have grown over the past

25 years to be the most important awards for Hispanic newspapers,

magazines, and now websites.

At

the NAHP Convention October 18-20, 2012 in San Diego awards will be

presented to publishers, journalists, editors, art directors &

marketing professionals. The National Association of Hispanic

Publications' José Martí Publishing Awards have grown over the past

25 years to be the most important awards for Hispanic newspapers,

magazines, and now websites.

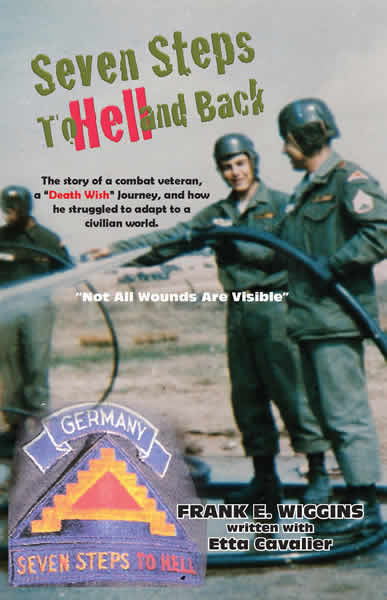

Frank

Wiggins is a Cold War era veteran who has suffered from PTSD since his

separation from the military in 1960. He considers himself very lucky

to have survived many years of a destructive lifestyle. Since a young

age he discovered he had a photographic memory and in the military, he

became an exceptionally well trained soldier.

Frank

Wiggins is a Cold War era veteran who has suffered from PTSD since his

separation from the military in 1960. He considers himself very lucky

to have survived many years of a destructive lifestyle. Since a young

age he discovered he had a photographic memory and in the military, he

became an exceptionally well trained soldier.

They

fought in WWI, according to family stories, he served in France.

Uncle Francisco was injured and received a purple heart medal.

He is buried at Roy N.M cemetery in the Veterans section.

They

fought in WWI, according to family stories, he served in France.

Uncle Francisco was injured and received a purple heart medal.

He is buried at Roy N.M cemetery in the Veterans section.

In

commemoration of Louisiana's 200th anniversary as a

state, which was celebrated back on April 30, Rolling

Stone Magazine put out a piece today,

In

commemoration of Louisiana's 200th anniversary as a

state, which was celebrated back on April 30, Rolling

Stone Magazine put out a piece today,

Many

slaves, for example, ran away to the Union Army. Hundreds fled to Camp

Parapet, a fortification just above the city, where the abolitionist

commanding officer, Brig. Gen. John W. Phelps, welcomed them. Even

those who were thought to be most loyal to their owners ran off.

“There are many instances in which house-servants, those who have

been raised by people, have deserted them,” complained Clara

Solomon, a teenager in the city.

Many

slaves, for example, ran away to the Union Army. Hundreds fled to Camp

Parapet, a fortification just above the city, where the abolitionist

commanding officer, Brig. Gen. John W. Phelps, welcomed them. Even

those who were thought to be most loyal to their owners ran off.

“There are many instances in which house-servants, those who have

been raised by people, have deserted them,” complained Clara

Solomon, a teenager in the city.