1576 |

1633

|

1708 |

1719

|

1720 |

1726

|

1732 |

1735

|

1736 |

1737

|

1739 |

1740

|

1747 |

1751

|

1756 |

1757

|

1758 |

1760

|

1761 |

1762

|

1764 |

1769

|

1772 |

1773

|

1774 |

1777

|

1778 |

1781

|

1782 |

1786

|

1787 |

1788

|

1789 |

1790

|

1791 |

1792

|

1793 |

1794

|

1795 |

1796

|

1797 |

1798

|

1799 |

1800

|

1801 |

1802

|

1803

Introduction

The Church in

Louisiana and Florida, 1513-1815

Bibliographical

Note

Provenance

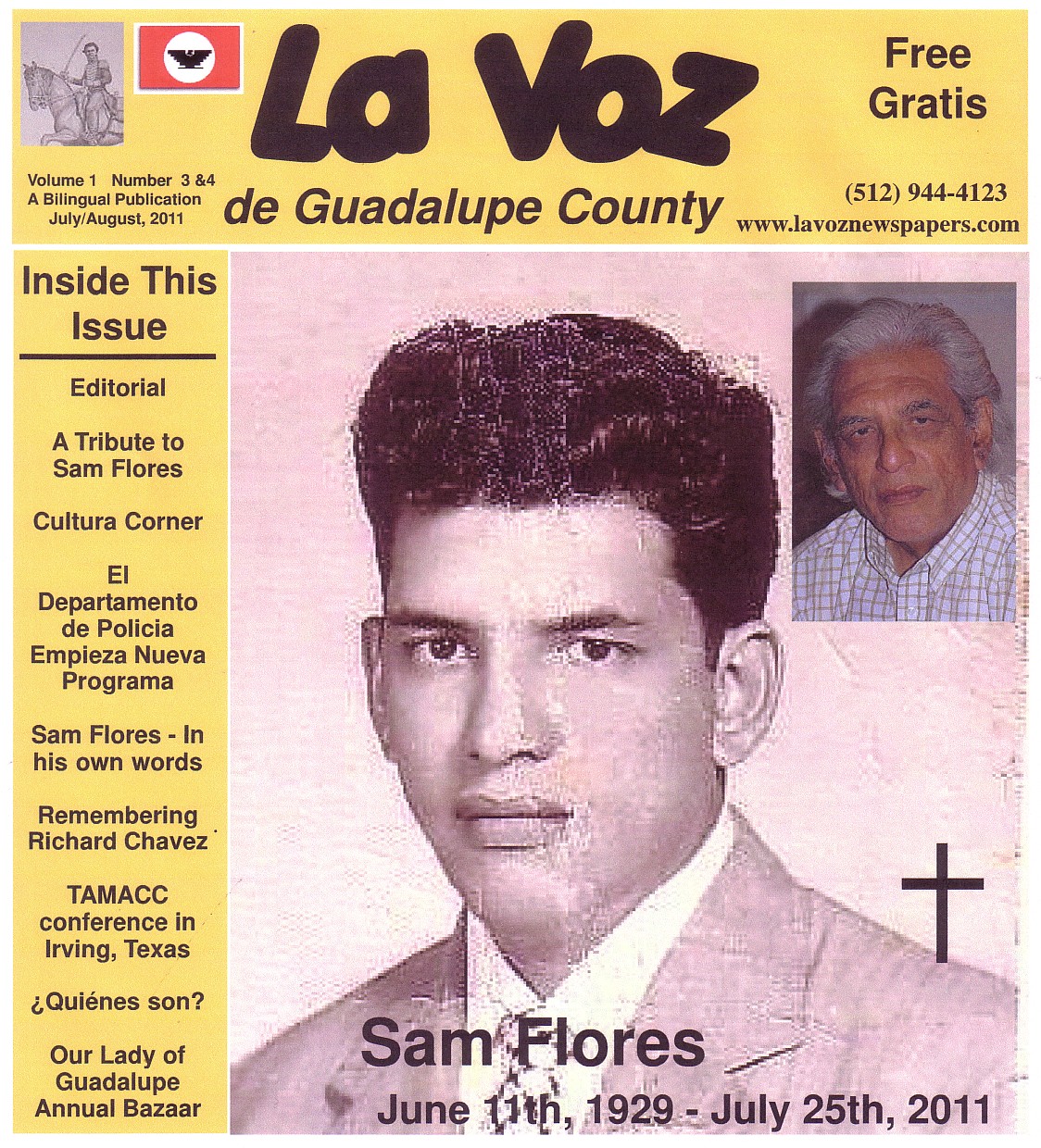

Editorial

Procedure

Explanation of

the Calendar

Description of

the Collection

Alphabetical List

This guide and the accompanying rolls of microfilm are being published

by the University of Notre Dame archives under the sponsorship of the

National Historical Publications Commission.

The initial step in the program of publishing manuscripts having a

significant relevance to American History was taken in 1950 when

President Truman directed the National Historical Publications

Commission to draw up a plan for making such material readily

available for scholarly use. The Commission's Report was submitted to

President Eisenhower in 1954 and, in the succeeding decade, the

Commission encouraged the editing and publishing of various

collections, including the Jefferson Papers, the Adams Papers, and the

Franklin Papers.

In 1963 the Commission recommended to President Kennedy a ten-year

program of publication to be financed by the Federal Government as

well as by private sources. The Report, stressing the importance of a

citizenry well instructed in American History, recommended the

increased use of microfilm as a means of making available, as

inexpensively as possible, significant source material. In 1964

Congress enacted legislation authorizing the Commission's grant

program and the first funds were allocated for the support of projects

deemed worthy of approval by the Commission. Early in 1965 the

Commission approved a grant to the University of Notre Dame Archives.

The project was commenced in June, 1965.

In the task of preparing the Records of the Diocese of Louisiana

and the Floridas for microfilming we have been aided by Mr. Norman

Leslie Smith III, Mr. Charles Gensheimer, Mrs. Janet Ubelhart, and

Miss Mercedes Muenz. A debt of gratitude is owed to Dr. Oliver W.

Holmes, to the National Historical Publications Commission, and

especially to Mr. Fred Shelley of that Commision for his wise counsel

and encouragement. The information acquired at the Frebruary, 1966,

meeting at the National Archives in Washington D.C. of representatives

from institutions preparing microfilm publications under grant from

the Commission has been invaluable.

Lawrence J. Bradley, LL.B., M.A.

Manuscripts Preparator

Notre Dame, Indiana

April 1967

Although the Diocese of Louisiana and the Floridas, later to be known

as the Diocese of

New

Orleans, was formally erected only on April 25, 1793, by Pope Pius

VI, the area embraced within its confines had had a long

ecclesiastical history prior to that time. Following the discovery of

Florida by Ponce de Leon in 1513, Spain made several attempts to

explore and tame the wild lands of southeastern North America. Acting

by virtue of the Patronato Real de Indias or Royal Patronage of the

Indies -- a recognition accorded to the Spanish sovereigns by the

Roman Pontiffs of extensive control over and responsibility for the

ecclesiastical administration of the Indies -- King Charles I, pending

approval from the Holy See, provided for the erection of a Diocese of

Florida which was to embrace the whole territory along the Gulf coast

from the Cape of Florida to the Rio Grande.

The proposed See, however, never actually materialized, and the

Fransiscan, Juan Suarez, who had been chosen to be its bishop,

perished while accompanying the ill-fated de Narvaez expedition to the

area. Following the failure of De Soto's expedition (1539-1543), Spain

made no further effort to conquer and colonize the lands bordering the

Mississippi. Instead, she confined her efforts to Florida and the

southwest.

The French, solidly established in Canada by the mid-seventeenth

century, soon began to encroach upon the territory to the south which

had been claimed initially by Spain. After La Salle and his party

reached the mouth of the Mississippi in 1682, Louisiana became

definitely French territory. Here, as in the Spanish domains, Church

and State were bound closely together with the French monarch

exercising considerable control over and bearing considerable

responsibility for ecclesiastical affairs. After an initial attempt to

establish an independent Viciariate Apostolic for the area failed

because of the opposition of Bishop St. Vallier of Quebec, Louisiana

in 1688 was recognized formally as belonging within the Diocese of

Quebec.

In 1699 the priests of the Seminary of Quebec, an outgrowth of the

Seminary of Foreign Missions at Paris, began their priestly labors in

the area. They were soon joined by the Jesuits. In 1712 Louisiana

became a proprietary colony under the wealthy Antoine Crozat who had

obtained a fifteen-year lease from the French crown. Finding the

venture to be unprofitable, Crozat relinquished his lease in 1717. The

colony then reverted to the French crown which turned it over to John

Law's Company of the West. The obligation of providing for the

religious needs of the territory, which included the nomination and

maintenance of priests as well as the building of churches, devolved

upon Law's Company.

Actual ecclesiastical supervision over the territory continued to

be exercised by remote control through a local vicar general. Although

a Frech Capuchin, Louis-Francois Duplessis de Mornay, was chosen

coadjutor to Bishop St. Vallier of Quebec in 1713 and, as such,

entrusted with the care of Louisiana, he never visted the colony. In

1717 Spain showed a renewed interest in the westen part of the

territory and a mission, staffed by Spanish Franciscans, was

established at Los Adayes, twenty-one miles from Natchitoches. In 1720

French Carmelites were introduced into the territory but they were

soon replaced by French Capuchins from the Province of Champagne under

an agreement between the Company of the West, the Capuchins, and

Bishop de Mornay. The Capuchins were to serve the French posts in the

territory while the Jesuits were to continue serving the Indian

missions.

Unfortunately, years of friction ensued between the two missionary

groups until the eventual suppression of the Jesuits in the colony in

1763 following their suppression in France. In 1727 a band of French

Ursuline Nuns arrived in New Orleans where they established a convent

and a school for girls and began the task of attending to the Royal

Hospital. In 1731 the colony again changed hands as the Company of the

West relinquished its lease and returned it to the direst supervision

of the French crown. There it remained until it was ceded to Spain by

the secret treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. The actual transfer,

however, was not completed until 1769 when Spanish forces

Captain-General Alexander O'Reily succeeded in putting down a

rebellion of a segment of the French population.

Meanwhile, Florida, which from the time of its discovery had

remained Spanish territory, was passing into the hands of England,

having been ceded to her by the Treaty of Paris in 1763. There, St.

Augustine had been founded in 1565 and missionary activity had been

undertaken first by secular clergy, then by Jesuits, and finally by

Franciscans. Although the Franciscans had succeeded in establishing a

number of flourishing missions among the Indians, these were dealt a

blow from which they never recovered by the destructive English raids

of 1702-1704 led by onetime Governor James Moore of Carolina. In 1709

Dionisio Resino was named auxiliary to the Bishop of Santiago de Cuba,

the diocese to which Florida belonged, and entrusted with the care of

Florida. After three weeks' residence in the territory he was so

disheartened by the conditions prevailing there that he returned to

Cuba.

In 1735 Francisco de San Buenaventura y Tejada, appointed auxiliary

to the Bishop of Santiago de Cuba in 1731, finally arrived in Florida.

When he was translated to the See of Yucatan in 1745, Pedro Ponce y

Carrasco was named his successor but did not sail to Florida until

nine years later. Once there, he remained only nine months. In

1762-1763, on the eve of its cession to England, the territory

received an impromptu episcopal visitation by Bishop Pedro Augustin

Morrell of Santiago de Cuba as he was returning from English captivity

by Charleston, South Carolina.

While acquiring Florida from Spain, England in 1763 also acquired

from France a thin strip of territory extending westward along the

Gulf to the Mississippi. By a royal proclamation of the same year two

royal colonies were formed of the territory thus acquired: East

Florida, which extended west to the Charrahoochee River and had St.

Augustine as its capital, and West Florida, which extended west from

the Chattahoochee River to the Mississippi and had Pensacola as its

capital. Although the British sovereign pledged to allow Catholics

freedom of worship insofar as the laws of Great Britain permitted, a

wholesale exodus of the Spanish population took place, and as a result

Catholicism all but disappeared from the area. A small revival came

five years later when Andrew Turnbull, a Scottish physician turned

colonizer, established a plantation composed largely of Catholic

Minorcans at New Smyrna on the Atlantic coast, seventy-four miles

south of St. Augustine.

Before long the territory was once again in Spanish hands. In 1779

Spain officially threw in her lot with the American revolutionaries

and attacked British West Florida. Mobile fell to her in 1780 and

Pensacola in 1781. The remainder of the Floridas was returned to her

by treaty in 1783. Once again under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of

the Bishop of Santiago de Cuba, the Church in the territory was

confronted with a twofold task: the reduction of Spaniards, Minorcans

and French to ecclesiastical unity under the Spanish Patronato Real

and the conversion of Anglo-American settlers. While Bishop Santiago

Joseph de Hechavarria y Elguezua of Santiago de Cuba was primarily

responsible for ecclesiastical affairs in these remote areas of his

diocese, the actual supervision was entrusted to two vicarios, Father

Thomas Hassett, an Irish priest from Spain, who was sent to reside at

St. Augustine and care for East Florida, and Father Cirilo Sieni de

Barcelona who resided in New Orleans and was charged with the care of

the joint province of Louisiana - West Florida.

By this time, the Spanish authorities had come to recognize the

need for a resident bishop on the mainland. A proposal was drawn up

for the appointment of an auxiliary to the Bishop of Santiago de Cuba

to reside in New Orleans. The plan was approved by Rome and in 1781

King Charles III of Spain asked Bishop Hechavarria to propose Father

Cirilo for the post. Although Cirilo was officially notified of this

appointment on July 18, 1782, bulls were not issued by Pope Pius VI

until June 6, 1784, and Cirilo's consecration did not take place until

March 6, 1785.

Meanwhile, it had become evident that the administrative work of

the vast Diocese of Santiago de Cuba was too great a burden for its

bishop. Eventually, by a consistorial decree of September 10,1787,

that diocese was split in two and the new Diocese of St. Christopher,

with its episcopal seat at Havana, was erected. The mainland

territories of Louisiana and the Floridas were placed under its

jurisdiction. Bishop Felipe Joseph Trespalacios of Puerto Rico was

transferred to the new diocese and Bishop Cirilo became his auxiliary.

Subsequent events, marred by friction between the two bishops, soon

demonstrated the unfeasibleness of such a division of authority. By

1791 King Charles IV had decided upon a further division of the

Diocese of St. Christopher. Rome was consulted and on April 25, 1793,

Pope Pius VI issued a bull establishing the Diocese of Louisiana and

the Floridas. Auxiliary Bishop Cirilo was recalled and Luis Ignacio

Maria de Penalver y Cardenas, a forty-four-year-old native of Havana,

was named bishop.

Consecrated at Havana on April 25, 1795, Bishop Penalver arrived in

New Orleans on July 17 and took formal possession of his See on July

24. He was confronted immediately with a multitude of distressing

problems. A general spirit of indifference and even scorn for

religion, fostered in part by the spread of Voltairianism and

revolutionary ideologies from France, combined with the perennial

shortage of priests, the distinct aversion of the French population

for everything Spanish, and the deeply rooted moral abuses that had

developed under pioneer colonial conditions to burden the bishop

during his six-year administration of the diocese. Eventually, even

his great zeal could no longer sustain him in the face of such

appalling conditions and he petitioned the king for a change to some

other diocese. His request was granted. On July 29, 1801, Rome

formally announced his appointment to the Archdiocese of Guatemala.

Envisioning only a brief interval before the arrival of a successor,

he appointed Father Thomas Hassett administrator and Father Patrick

Walsh assistant administrator before leaving Louisiana in November of

that same year.

Events were to prove Penalver's prognostication wrong and to

undermine the arrangements he had made for the interim administration

of the vacant See. Louisiana was to be without a bishop for the next

fourteen years. Although Francisco Porro y Peinado, a Spanish Minim,

was selected for the post early in 1801, rumors of the impending

transfer of Louisiana from Spain to France caused him to delay his

departure. Eventually in 1803, before he had ever formally taken

possession of the diocese, he was transferred to the Diocese of

Tarazona in Spain. The unexpected duration of the period of

administration and the complications created by the retrocession of

the Louisiana Territory to France and its subesequent sale to the

United States in 1803, which brought to an abrupt end the close

relationship that had existed between Church and State, combined to

create for Father Hassett unexpected difficulties, not the least of

which was an end to the financial subsidies which the state had

granted to the Church under both the Spanish and French regimes.

The situation worsened upon the death of Hassett in 1804. Although

Father Walsh then claimed authority by virtue of his appointment as

assistant administrator, his claim was disputed by Father Anthonio de

Sedella, the Capuchin rector of the Cathedral, who unfortunately had a

substantial popular following. Likewise, in 1806 Bishop Juan Jose Dias

de Espada of Havana disputed Walsh's authority in Florida which had

remained Spanish territory. Although Rome in 1806 had authorized

Bishop John Carroll of Baltimore to assume temporary supervision of

the vacant See, the extent of his jursidiction was not specifically

spelled out, and as a result it was not clear whether Florida was

included in the territory entrusted to him. The Bishop of Havana

continued to exercise jurisdiction over Florida, and in Louisiana the

authority of the administrators appointed by Carroll continued to be

challenged by Father Sedella and his followers. Finally, in 1815

Louis-Guillaume-Valentin DuBourg, who had been acting as

administrator, was named bishop. Although even his authority was

contested at times by Sedella and although the question of Florida

remained unsettled until the transfer of the territory to the United

States in 1821, the diocese once again had a bishop.

Brief general accounts of the Catholic Church in colonial Louisiana

and Florida may be found in the first two volumes of John Gilmary

Shea's pioneering four-volume

History of the Catholic Church in the

United States (New York, 1886). Although now outdated, Shea's work

still contains a wealth of information.

More specifically relating to the Church in Louisiana are Roger

Baudier's The Catholic Church in Louisiana (New Orleans, 1939),

Jean Delanglez's The French Jesuits in Lower Louisiana (1700-1763)

(Loyola University of New Orleans, 1935) and Charles Edwards O'Neill's

Church and State in French Colonial Louisiana: Policy and Politics

to 1732 (Yale University Press, 1966), all of which contain

extensive bibliographies citing both published and archival sources. A

special supplement to Catholic Action of the South, XI (July

29, 1943), no. 35, edited by Roger Baudier and published in

celebration of the sesquicentennial of the Diocese of New Orleans, has

been very helpful and informative.

The history of Catholicism in Florida has been traced recently in

Michael V. Gannon's The Cross in the Sand: The Early Catholic

Church in Florida 1513-1870 (University of Florida Press, 1965).

An earlier but still very useful account of a more limited period of

that history os Michael J. Curley's Church and State in the Spanish

Floridas (1783-1822) (Catholic University of America Press, 1940).

Both Gannon and Curley also supply extensive bibliographies.

Finally, among the many useful secular histories are Alcee

Fortier's four-volume History of Louisiana (Paris, 1904), Henry

E. Chamber's three-volume History of Louisiana (American

Historical Society, 1925), and Caroline Mays Brevard's two-volume History

of Florida from the Treaty of 1763 (The Florida State Historical

Society, 1924).

Early in the 1880's Professor James F. Edwards, librarian of the

University of Notre Dame, aware that irreplaceable items pertaining to

the history of Catholicism in America were constantly in danger of

being lost through neglect, carelessness or willful destruction, began

to implement a plan which he had conceived for establishing at Notre

Dame a national center for Catholic historical materials. The frail

but hard-working Edwards set about acquiring all kinds of relevant

items, including relics and portraits of the bishops and other

missionary clergymen, a reference library of printed materials, and an

extensive manuscript collection.

To the manuscript collection, in which he hoped to include all the

existing diocesan archives as well as the papers of outstanding

Catholic clergymen and laymen, he gave the designation "Catholic

Archives of America." Prominent clergymen such as Archbishop

William Henry Elder of Cincinnati, Archbishop Francis Janssens of New

Orleans, and Father Ignatius Horstmann of Philidelphia, and laymen

like Martin I.J. Griffin, editor of the American Catholic

Historical Researches, and John Gilmary Shea, the pioneering

historian of the Catholic Church in the United States, lent their

active and very helpful assistance. Thousands upon thousands of items

which have been a boon to historians were acquired.

Unfortunately, Edwards had not the time, nor the money, nor the

health necessary to bring his project to completion. Although the

collection has been augmented under successors, Father Paul J. Foik,

C.S.C., and Father Thomas T. McAvoy, C.S.C., the present Archivist of

the University of Notre Dame, the ambitious scheme for an official

American Catholic archives had to be given up in 1918 when Canon Law

was changed so as to require each bishop to maintain his own archives.

The Records of the Diocese of Louisiana and the Floridas

(1576-1803), subject of this microfilm publication, are part of a

larger group of papers pertaining to the Archdiocese of New Orleans

down to 1897. The collection was acquired in the 1890's by Edwards

through the generosity of Archbishop Janssens. Everything for the

period in question, except photostatic copies made for use in the

Notre Dame Archives and duplicates of a few items, has been filmed.

The material relating to the period after 1803 has not been filmed

because there are restrictions upon its use. It may be consulted,

however, at the Archives with the permission of the Archivist.

Although the first two items in the collections are dated 1576 and

1633, respectively, and there are a number of items for the period

from 1708 to 1783, the great bulk of material pertains to the years

1786 through 1803. Consulted until now mainly by historians of the

Catholic Church, it should prove useful also to secular historians

because of the close connection between Church and State which existed

during both the French and Spanish colonial regimes in Louisiana and

Florida. Photostatic copies of all the items in the collection, as

well as photostatic copies of the calendars for those portions that

have already been calendared, are in possession of the New Orleans

Archdiocesan Archives.

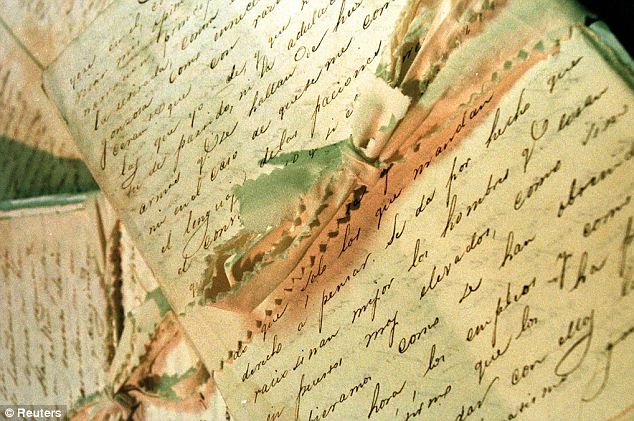

According to a tradition, most of the papers of Bishop Penalver, as

well as those of his successor, Bishop DuBourg, were destroyed during

the Civil War. Bricked up in a chimney for safekeeping when New

Orleans was threatened by Union troops, it was discovered later that

someone had neglected to close the chimney at the top and that,

consequently, rain had poured in and turned the papers into a mass of

pulp. Whether copies of at least some of the items thus lost have

survived in the dossiers pertaining to Penalver's administration of

the diocese or whether the papers destroyed were personal papers or

official papers which dealt with other matters is not known.

In addition to this collection in the University of Notre Dame

Archives, there are numerous other collections both in the United

States and in foreign countries which pertain to the ecclesiastical as

well as to the secular history of colonial Louisiana and Florida.

Although far too numerous to list here, references to these

collections may be found in Philip M. Hamer's Guide to Archives and

Manuscripts in the United States (Yale University Press, 1961),

the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections, Roger

Baudier's The Catholic Church in Louisiana (New Orleans, 1939),

Jean Delanglez's The French Jesuits in Lower Louisiana (1700-1763)

(Loyola University of New Orleans, 1935), Charles Edwards O'Neill's Church

and State in French Colonial Louisiana: Policy and Politics to 1732

(Yale University Press, 1966), Caroline Mays Brevard's two-volume History

of Florida from the Treaty of 1763 (Florida State Historical

Society, 1934), Michael V. Gannon's The Cross in the Sand: The

Early Catholic Church in Florida 1513-1870 (University of Florida

Press, 1965), and Michael J. Curley's Church and State in the

Spanish Floridas (1783-1822) (Catholic University of America

Press, 1940). The Florida State Historical Society has published in

several volumes a number of manuscripts and documents pertaining to

the history of their State. Documents edited by Manuel Serrano y Sanz

and pertaining to both Florida and Louisiana may be found in Documentos

Historicos de la Florida y la Luisiana Siglos XVI al XVIII

(Madrid, 1912). For Louisiana itself there are James Alexander

Robertson's two-volume edition, Louisiana under the Rule of Spain,

France, and the United States 1785-1807 (Cleveland, 1911), and a

recently published collection of items edited by Jack D.L. Holmes, Documentos

Ineditos para la Historia de la Luisiana 1792-1810 (Madrid, 1963),

which forms volume XV in the Coleccion Chimalistac de Libros y

Documentos acerca de la Nueva Espana.

The Records of the Diocese of Louisiana and the Floridas had been

arranged chronologically and calendered prior to the inception of the

present microfilm project. Where the particular item is a simple

letter or document it was calendared as such. However, where, as often

occurs, the particular item consists of a large dossier of documents

or copies of documents and accounts of various proceedings, it was

given a specific date -- often that of the last document or notation

contained therein -- and a single inclusive calendar was drawn up for

the entire dossier. Such dossiers will be found on the microfilm under

the date assigned to them in the calendars although they quite often

contain material for earlier years. Specific documents within each

dossier appear in the same order that summaries of them appear in the

calendars.

In a number of instances particular documents are so badly

mildewed, water-stained or faded that it has been impossible, without

risking the complete destruction of certain documents, even to

separate various pages for filming. Under these circumstances targets

have been used to explain the difficulty, the calendars for the items

in question have then been filmed and, finally, whenever possible, the

items themselves have been filmed, taking particular care to secure as

readable an image as circumstances permit. In referring to the

calendars the user is cautioned that they were prepared as an aid to

research not as a substitute for the documents themselves, and that,

consequently, the University of Notre Dame Archives does not guarantee

their accuracy.

Since the particular dates of various items often do not appear on

the face of the items themselves and since documents of various dates

are often filmed together under one date because calendared under that

date, targets bearing the date under which they were calendared have

been prepared and filmed before each such item or group. Items dated

only by month and year appear at the beginning of that month. Items

dated only by year appear at the beginning of that year. In addition,

an alphabetical list, which appears both in this Guide and on the

first roll of microfilm and which includes the names of the authors of

the various items to be found in the collection as well as the names

of particular persons or places under which various dossiers have been

calendared, has been prepared as part of the present microfilm

project. This list, used in conjunction with the calendars which have

been filmed on the first roll of microfilm and the date targets which

appear before each item or group of items, should enable the

researcher to locate quickly any particular item of interest.

As an aid to indentification and citation, each frame on each roll

has been given a specific number which will be found on the lower

right-hand corner of the frame. No matter how careful the editors and

filmers are, there are bound to be cases where, after a whole roll has

been filmed, it becomes necessary to either add or delete a frame.

Obviously, this throws off the numerical sequence of the frame

numbers. To meet this difficulty we have employed the following

technique: when a frame has had to be added, we have used the number

of the preceding frame and added an "A" to it; when a frame

has had to be deleted, the number assigned to that frame simply does

not appear. While these procedures are a compromise with perfection,

they are realistic in terms of the problems which unfortunately arise

in microfilming, especially when the alternative might well involve

several refilmings of an entire roll. Throughout the microfilm targets

have been used to identify various items and point up special problems

that have arisen in microfilming the collection. Targets have not been

used in cases, such as for torn or stained pages, where particular

defects should be readily apparent.

(1) 1758 Nov. 15

(2) Rochemore, Vincent Gaspard Pierre de, Chevalier, Councilor

of the King in Council, Commissaire general of the Marine, Ordinateur

of La.

(3) New Orleans, (Louisiana)

(4) Appoints Monsieur

(Louis Alexandre) Dolaunay, church

warden of the church of

St. Louis in

New Orleans to

examine and finish the accounts of the old churchwardens and to

examine old matters concerning the property of the same church.

(5) IV-4-a

(6) A.D.S. 1p. 8vo. (French)

(7) 3

1. Date of the Document

This can be either the date appearing in the text of the document or,

in the absence of such a date, a date based upon some other evidence

and supplied by those who calendared the particular document. In the

latter case it would appear in parentheses. A document dated simply by

month and year is filed before other documents for that month, and one

dated simply by year is filed before other documents for that year. In

the case of a large dossier, a date appearing in this position on the

card would indicate the date under which particular dossier will be

found. Other dates which might be found further on in the calendar

would indicate merely the specific dates of the documents within the

particular dossier.

2. Author of the Document

Parentheses around this item or portions of it would indicate that the

information so appearing had been supplied by the person who

calendered the particular document.

3. Point of Origin

Parentheses around this item or portions of it would indicate that the

information so appearing had been supplied by the person who

calendared the particular document.

4. Summary of the Text

The summary, depending upon the length of the text and the material

covered therein, might well run over onto successive cards. In such a

case the information appearing at the foot of this card would appear

only at the foot of the last card in the set. Items in the summary

which appear in parentheses have been supplied by the person who

calendared the document.

5. Location of the Document

This notation indicated where in the Notre Dame Archives this

particular document will be found. The Roman numeral indicates the

cabinet, the Arabic numeral the shelf, and the small letter the box.

In this particular case the item would be found in the first box on

shelf four of cabinet four.

6. Information about the Document

The notations given here indicate the nature of the particular item,

the language in which it is written, the number of pages, and the size

of those pages. For example, this item is a signed autograph document,

written in French, and consisting of one octavo size page. If the

document had been written in English, rather than French or some other

foreign language, no language indication would have been given. The

abbreviation A.D. would indicate an autograph document which had not

been signed. D.S. would indicate simply a signed document. A.L.S.

would indicate an autograph letter signed, A.L. would indicate an

autograph letter, and L.S. would indicate a signed letter.

7. Number of Cross References

This number indicates the number of duplicate copies which have been

made of the calendar.

The 809 items which comprise the Records of the Diocese of Louisiana

and the Floridas (1576-1803) are broken down, by year, as follows:

1576 1 1747 1 1774 1 1792 18

1633 1 1751 1 1777 1 1793 19

1708 1 1756 1 1778 2 1794 11

1719 1 1757 1 1781 1 1795 40

1720 1 1758 6 1782 1 1796 105

1726 1 1760 1 1783 1 1797 67

1732 1 1761 1 1786 15 1798 46

1735 1 1762 1 1787 17 1799 42

1736 3 1764 2 1788 24 1800 50

1737 1 1769 1 1789 30 1801 64

1739 1 1772 2 1790 48 1802 92

1740 1 1773 1 1791 1 1803 80

Roll One: Introduction; Alphabetical List; and Calendars,

1576-1803

The major portion of this roll in composed of the University of Notre

Dame Archives' calendars for the Records of the Diocese of Louisiana

and the Floridas, 1576-1803. These calendars typed on 3" by

5" index cards, have been placed in chronological order and

filmed eight cards to a frame. Those who refer to them are

particularly cautioned that they have been filmed as an aid to the use

of the microfilm and not as a substitute for the documents themselves.

Consequently, the University of Notre Dame Archives guarantees neither

the accuracy nor their completeness.

Roll Two: 1576-1790

On this roll are to be found the earliest documents in the Collection.

Although the initial item in dated May 27, 1576, for the period up to

1786 there are only forty items. The great bulk -- one hundred and

thirty-four items -- pertains to the years 1786-1790. In general the

material on this and succeeding rolls relates to ecclesiastical

affairs and includes items pertaining to marriages, funerals,

dispensations, grants of indulgences, the assignment and transfer of

priests, and ecclesiastical finances. Throughout the film there are

various documents relating to matters of concern to both Church and

State which are indicative of the close relationship which existed

between the two.

Items of special interest include: a printed brochure contained two

letters, dated respectively 1632 and 1633, from Father Estevan de

Perea, Guardian of the Province of New Mexico, to Father Fransisco de

Apodaca, Commissary General of all New Spain, relative to missionary

activities; a partial list under date of Dec. 13, 1737, of those

killed by the Natchez Indians at Natchez and the Yazoos; two items,

dated Feb. 28, 1757, and Nov. 30, 1758, respectively, relative to the

finances of the Charity Hospital at New Orleans; several items, dated

respectively May 6, 1786, July 6 1786, Aug. 11, 1787, and Mar. 28,

1788, relative to quests for sanctuary by fugitives from justice; a

general summary, dated 1788, of the registry of persons in Louisiana,

at Mobile, and at Pensacola; a letter of Mar. 28, 1788, from Father

Valiniere to Father Sedella relative to religious requirements for the

settlement of Americans in Spanish territory; a Nov. 6, 1789, copy of

a royal decree for the establishment of a Maritime Fishing Company in

Louisiana; and an Aug. 17, 1790, dossier containing various royal and

papal decrees relative to a tax on ecclesiastical income. In several

instances, on this and succeeding rolls, where particular documents

are so badly stained, faded or deteriorated that it has been

impossible to obtain a completely legible image, the applicable

calendar has been also filmed before such documents.

Roll Three: 1791 - Jan. 1795

Many of the items on this roll are actually large dossiers containing

various documents relating to specific subjects. For example, the only

item for 1791 is a dossier under date of June 30 of documents

concerning the building of brick houses to be rented for the benefit

of the Church of St. Louis in New Orleans. Other items of interest

include: an April 10, 1793, dossier containing royal instructions in

regard to marriages among Protestants and between Protestants and

Catholics; a Dec. 21 1793, dossier of instructions for Father Joaquin

de Portillo, Vicar Forane of Louisiana, and for Father Theodoro Thirso

Henrique Henriquez, Advocate of the Royal Court of Mexico and Santo

Domingo, Vicar General Auxiliary to the Bishop of Havana, Vicar Forane

of Louisiana, and Ecclesiastical Judge for the Province of Louisiana;

and a Jan. 24, 1795, copy of Governor Carondelet's report to Spain

giving and account, which includes census figures, of the various

parishes in Louisiana.

Roll Four: Feb. 1795 - Feb. 1796

A large number of items on this roll reflect the presence of Luis

Penalver y Cardenas, first Bishop of Louisiana and the Floridas, who

arrived at New Orleans in July 1795. Items of special interest

include: an Aug. 24, 1795, dossier pertaining to the accounts for the

period from 1785 to 1791 of Antonio Ramis, majordomo of the fabrique

of the Church of St. Louis in New Orleans; a Sept. 19, 1795, dossier

relative to Bishop Penalver's visitation of the Hospital of Charity of

San Carlos at New Orleans; a 95-page dossier, dated Oct. 8, 1795, of

proceedings, indicative of the red tape that might be entailed under

the Spanish system of administration, carried on by Pedro Marin Argote

in order to obtain possession of several slaves allegedly erroneously

listed in the inventory of Father Antonio de Sedella's goods; an Oct.

9, 1795, dossier relative to an audit of the accounts of the Church of

St. Louis for the period from January 1791 to July 1795; a Dec. 22,

1795, dossier giving an account of Bishop Penalver's episcopal

vistitation of New Orleans; a copy of the regulations issued by King

Charles IV on Jan. 1, 1796, in regard to pensions for widows and

unmarried women; a 172 page dossier under date of Jan 15, 1796, of

documents relative to an official investigation, conducted in 1790, of

the accounts of the Church of St. Louis; and a Feb. 5, 1796, dossier

relative to a quest for sanctuary in the parish church at St.

Augustine, Florida by Santiago Duarte, a Spanish grenadier who had

been convicted of high treason for conspiring to deliver the fortress

of San Marcos to some French prisoners incarcerated therein. In

addition to the foregoing, a number of informative census reports for

various parishes in the diocese are scattered throughout the roll.

Roll five: Mar. 1796-Feb. 1797.

Once again, there are to be found scattered throughout this roll a

good number of informative parish census reports including an Oct. 1,

1796, report of parishes under the care of Father Pierre Josef Didier

in Illinois and Missouri. Other items of special interest include: a

175-page Mar. 30, 1796, dossier pertaining to an audit of the accounts

of the Parish of St. Gabriel at Iberville for the period from Oct. 21,

1785, to July 21, 1796: a dossier of Sept. 28, 1796, pertaining to a

quest for sanctuary in the church at Mobile; and a Nov. 21, 1796,

account of Bishop Penalver's visitation of Rapides, the village of the

Apalachee Indians, and Avoyelles. Finally, there is a dossier under

the date of Oct. 6, 1796, which contains a list of sixty-three

instructions for pastors in the diocese and a report on conditions in

the Cathedral Parish of New Orleans which embraced a large area

surrounding the city as well as the city itself. Unfortunately, many

of the pages of the last item are badly faded and very difficult to

read and, as a result, in many instances it will be impossible to

obtain clear, legible images on the film.

Roll Six: Mar. 1797 - Oct. 1797.

Among the items of special interest on this roll are: several parish

census reports; Easter duty reports of Aug. 18 and Aug. 19 listing the

names of members of the Second Battalion of the Infantry of Mexico; an

Easter duty report of Sept. 16 for the First and Second Battalions of

the Infantry of Louisiana; a dossier of Oct. 4, 1797, containing a

108- page account, with supporting documents, of the administration of

Antonio Ramis, majordomo of the fabrique of the New Orleans Cathedral,

for the period from 1785 to 1797; an Oct. 21 dossier of documents

relative to the accounts for the period from 1787 to 1797 of Juan

Gradenigo, majordomo of the fabrique of the church at Opelousas; and a

202-page dossier under date of Oct. 27 relative to proceedings against

Father Paul de Saint Pierre, pastor of Saint Genieve, Missouri.

Roll Seven Nov. 1797 - Aug. 1798.

Items of special interest on this roll include: various parish census

reports; a record under date of Dec. 17, 1797, of marriages and

burials at Cabahanoce for 1796; a 120-page dossier of April 18, 1798,

in regard to a quest for sactuary in the church at Mobile; a July 2,

1798, dossier relative to the appointment of a pastor for St. Charles

in the Illinois country; a July 22, 1798, dossier of documents, which

are unfortunatountry badly water-stained, concerning the establishment

of parishes at Avoyelles, Rapides, and Ovachita; an Aug. 7, 1798,

dossier relative to the removal of Father Francis Lennan to Bayou Sara

consequent to the surrender of Natchez, where he had been serving, to

the United States; and an Aug. 22, 1798, dossier of 112 pages relative

to the accounts of the fabrique of the New Orleans Cathedral for 1797.

Roll Eight: Sept. 1798 - Dec. 1799.

Items of special interest on this roll include: an extensive dossier

of Oct. 1, 1798, containing various original documents, manuscript

copies, and photostats from the Library of Congress, all of which

pertain to an investigation of the conduct of Father Juan Delvaux who

had been charged with inciting seditious principles: a dossier of Dec.

31, 1798, containing several parish census reports; a Jan. 17, 1799,

report on the finances of the Parish of St. Landry at Opelousas for

the years 1791 to 1798; an April 22, 1799, report on the finances of

the New Orleans Cathedral; and a dossier of Nov. 19, 1799, containing

an additional group for parish census reports as well as a statement

by Bishop Penalver in regard to the finances of the New Orleans

Charity Hospital.

Roll Nine: Jan. 1800 - May 1801.

Among the items of special interest on this roll are: various parish

census reports, including a dossier of Dec. 1800 which contains

reports for Upper Louisiana; a dossier of Mar. 25, 1800, which

consists of various royal dispatches, including one in regard to a tax

levy to meet the expenses of the war in Europe and one relative to the

conduct of ecclesiastical affairs pending the election of a successor

to Pope Pius VI; a May 23, 1800, dossier of correspondence with Father

Miguel de Andino of Puerto Rico in which Bishop Penalver reveals his

feelings about conditions in the Diocese of Louisiana and the Floridas;

and dossiers of July 14, 1800, and Feb. 25, 1801, relative to the

finances of the Cathedral.

Roll Ten: June 1801 - April 1802.

Among the items of special interest on this roll are: a number of

parish census reports; a dossier of Aug. 31, 1801, which contains an

inventory drawn up upon the appointment of a new archivist, of

documents in the archives dating back to 1771 and relating to

marriages and lawsuits; documents under date of Sept. 16, 1801, in

regard to a royal levy of certain excise taxes; correspondence of

Sept. 30, 1801, and Nov. 11, 1801, between Bishop Penalver and Manuel

de Salcedo, the Vice Royal Patron, in regard to the financial affairs

of the New Orleans Charity Hospital; a dossier of Oct. 17, 1801,

containing Bishop Penalver's controversial decree nominating Father

Thomas Hassett to serve as administrator of the diocese and a related

dossier of documents under date of Feb. 10, 1802, upon which occasion

Penalver acknowledged receipt of his bulls as Archbishop of Guatemala

and relinquished control of the diocese to Hassett; and a Mar. 11,

1802, dossier of testimony in regard to a quest for sanctuary in the

church at New Orleans by Matias Santa Iniesta of the Royal Artillery

who had been accused of killing another soldier, Antonio Suarez.

Roll Eleven: May 1802 - Nov. 1802.

The material on this roll reflects Father Thomas Hassett's

administration of the diocese pending the appointment of a new bishop.

Items of special interest include: a May 31 dossier in regard to the

financial accounts of the Cathedral; an Aug 18 account of the finances

of the Charity Hospital; and three dossiers of Nov. 5 in regard to

quests for sanctuary. Rumors of an impending retrocession of Louisiana

to France are reflected in a dossier of Nov. 18 concerning repairs to

the roof of the Cathedral and in a dossier of Nov. 26 in regard to the

financial accounts of the Cathedral.

Roll Twelve: Dec. 1802 - Dec. 1803.

The material on this roll reflects Father Hassett's continuing

administration of the diocese as well as the problems created by the

retrocession of the province to France in 1803. Items of special

interest include: several parish census reports; a number of dossiers

which contain inventories of the goods of the various parishes in the

diocese along with a declaration by the respective pastors as to

whether or not they wished to remain in the province after its

transfer to France; several dossiers in regard to the disposal of

slaves by the Ursulines in view of the impending transfer; documents

under date of April 2 and April 4, 1803, pertaining to the surrender

of church vestments and vessels to French authorities by relgious

communities; a May 4, 1803, dossier of accounts for the Cathedral for

the last two months of 1802; May 26 and May 27, 1803, dossier in

regard to a quest for sanctuary in the church at New Orleans; a Nov.

29, 1803, set of instructions for the ceremonies scheduled for the

next day for the transfer of the province from Spain to France sent to

Father Hassett by Manuel de Salcedo, the Spanish Governor, and

Sebastian Calvo de la Puerta y O-Farrill, Marquis de Casa Calvo, the

official designated by the King of Spain to make the actual transfer;

and another dossier of Nov. 29, 1803, the contents of which include

declarations of intent to remain in or to leave the province by the

clergy of New Orleans as well as a printed copy of the actual transfer

proclamation setting forth the limits of the territory and provisions

for individuals, for pensions, for ecclesiastics, and for religious

houses.

A B

C D

E F

G H

I J

K L

M N

O P

Q R

S T

U V W

X Y

Z

Alphabetical List

This list contains the names of the authors of the various items to

be found in the collection, as well as the names of particular persons

and places under which various dossiers in the collection have been

calendared. Dates have been given in the same chronological sequence

in which the items themselves have been microfilmed. Where the item is

dated only by month and year, it will be found at the beginning of

that month. Where it is dated only by year, it will be found at the

beginning of that year. In a few instances, namely in the case of

enclosures and certain items which were filed and consequently have

been calendared and filmed with other items, two dates have been

given: first, the date of the item itself, and second, in parentheses,

the date of the item with which it has been filmed. For example,

Saturnino Domine's letter of March 12, 1796 is listed thus: 1796 March

(encl'd in 1796 March 22, Archbishop Despuig y Dameto to Bishop

Penalver y Cardenas). On the microfilm the letter will be found by

referring to the date of the item in parentheses. Where the particular

item is a simple letter or document, not part of a larger dossier, the

date given is that of the letter or document itself. However, where

the item -- in many cases merely a copy of the original -- is to be

found in a larger dossier, the date given is that under which the

dossier has been calendared and, consequently, filmed. In most cases

this is actually the date of the last item in the particular dossier.

In order to avoid any confusion that this might cause, targets bearing

the date of the calendar have been filmed before each item or group of

items which is the subject of a specific calendar. To locate the

various items within particular dossiers more specifically, reference

should be made to the calendars which have been filmed on the first

roll of microfilm in the same chronological order in which the

documents themselves have been filmed. By using this list in

conjunction with the calendars and the date targets, the researcher

should be able to locate quickly any particular items of interest.

Sent by deville@provincialpress.us

I

was born in Pomona, California to two traditional Catholic Hispanic

parents. At the age of four I moved from Pomona to Upland, California.

Since then I have grown up striving to be a good student and dedicated

member of the community. Throughout my life I have always looked towards

my parents for inspiration.

I

was born in Pomona, California to two traditional Catholic Hispanic

parents. At the age of four I moved from Pomona to Upland, California.

Since then I have grown up striving to be a good student and dedicated

member of the community. Throughout my life I have always looked towards

my parents for inspiration.

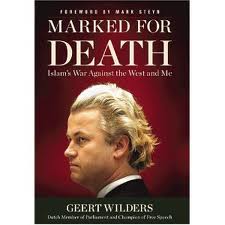

Marked for Death by Geert Wilders

Marked for Death by Geert Wilders

The

Center for Latino Policy Research (CLPR) is an organized research

unit at the University of California, Berkeley. We form part of the

Institute for the Study of Societal Issues. CLPR was established in

1989 in response to a wave of student protests on campus demanding

that the University of California be more responsive to the needs of

the state's growing Latino population. In response, the state

legislature passed SCR43, which led to the creation of the

University of California Committee on Latino Research (UCCLR),

housed in UC's Office of the President (UCOP). UCCLR funded

Latino-focused centers on every UC campus (except UCSF). Each center

then also received campus support and/or funding. Unfortunately,

UCOP decided to eliminate UCCLR in 2008; CLPR continues to receive

support from the Berkeley campus, but at a significantly reduced

level. We remain the only Latino-focused research center on the

Berkeley campus.

The

Center for Latino Policy Research (CLPR) is an organized research

unit at the University of California, Berkeley. We form part of the

Institute for the Study of Societal Issues. CLPR was established in

1989 in response to a wave of student protests on campus demanding

that the University of California be more responsive to the needs of

the state's growing Latino population. In response, the state

legislature passed SCR43, which led to the creation of the

University of California Committee on Latino Research (UCCLR),

housed in UC's Office of the President (UCOP). UCCLR funded

Latino-focused centers on every UC campus (except UCSF). Each center

then also received campus support and/or funding. Unfortunately,

UCOP decided to eliminate UCCLR in 2008; CLPR continues to receive

support from the Berkeley campus, but at a significantly reduced

level. We remain the only Latino-focused research center on the

Berkeley campus.

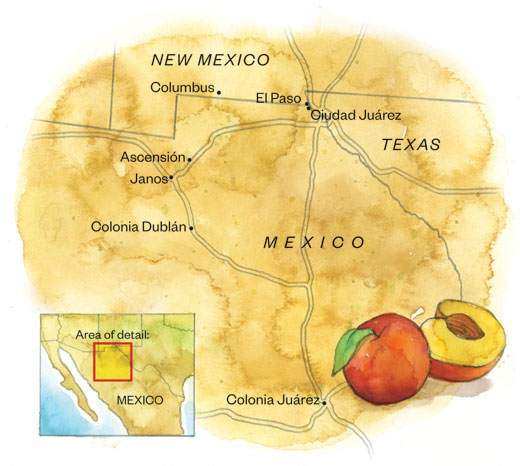

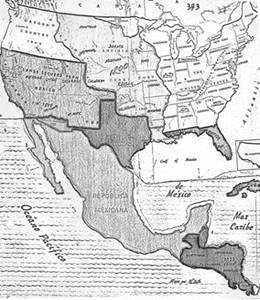

Geronimo

{jur-ahn'-i-moh}, or Goyathlay ("one who yawns"), was born

in 1829 in what is today western New Mexico, but was then still

Mexican territory. He was a Bedonkohe Apache (grandson of Mahko) by

birth and a Net'na during his youth and early manhood. His wife, Juh,

Geronimo's cousin Ishton, and Asa Daklugie were members of the Nednhi

band of the Chiricahua Apache.

Geronimo

{jur-ahn'-i-moh}, or Goyathlay ("one who yawns"), was born

in 1829 in what is today western New Mexico, but was then still

Mexican territory. He was a Bedonkohe Apache (grandson of Mahko) by

birth and a Net'na during his youth and early manhood. His wife, Juh,

Geronimo's cousin Ishton, and Asa Daklugie were members of the Nednhi

band of the Chiricahua Apache.

Blesilda Candida Epifania Guia Mueller Ocampo, popularly known as "Bessie" Ocampo made history as the first Filipina to enter the semi finals of the prestigious Miss Universe pageant. She won the Miss Philippines 1954.

Blesilda Candida Epifania Guia Mueller Ocampo, popularly known as "Bessie" Ocampo made history as the first Filipina to enter the semi finals of the prestigious Miss Universe pageant. She won the Miss Philippines 1954.  In 1954, Ma. Candida Blesilda "Bessie" Mueler

Ocampo, a UST architecture freshman, was the first Filipina to land among the 15 semi-finalists. She was in London as part of her prize for winning the Boys Town Miss Philippines contest when she was asked to represent the country in the 1954 Miss Universe Pageant.

In 1954, Ma. Candida Blesilda "Bessie" Mueler

Ocampo, a UST architecture freshman, was the first Filipina to land among the 15 semi-finalists. She was in London as part of her prize for winning the Boys Town Miss Philippines contest when she was asked to represent the country in the 1954 Miss Universe Pageant.