|

Introduction.

The author had the good fortune to interview Mrs Alice Vidaurri

Anaya over the phone on December 14, 2011. Her mother, Soledad Vidaurri,

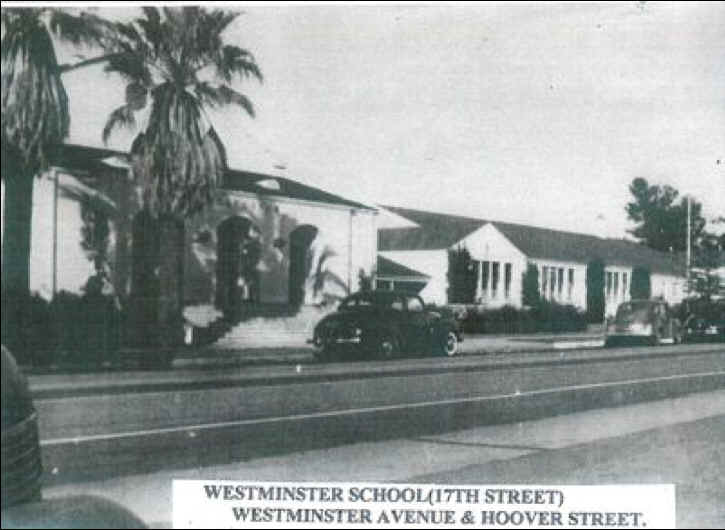

took her three children as well as brother’s three to register them at

the White Westminster Main School on Seventeenth Street in Westminster,

California. This happened in

1944. Gonzalo Méndez Sr. was the lead plaintiff in Méndez

et al. vs. Westminster et al.

What

took place at the Westminster Main School set off a series of critical

events that led to the historic lawsuit that overturned the de facto, de jure

segregation of Mexican heritage students in the public schools of Santa

Ana, Garden Grove, El Modeno, and Westminster.

In

the article the author uses the term “Mexican” to refer to Mexicans

and Mexican Americans. “Whites” or “Anglos” mean persons of

Anglo American cultural heritage. These names along with “Americans”

and “Anglo-Saxon” were in vogue by the turn of the twentieth

century.

The

author expresses his heartfelt gratitude to his former classmate at

Hoover (1944-45) and Seventeenth Street School (1945-46), Gonzalo Méndez Jr, who helped me connect with his cousin, Alice

VIDAURRI Anaya.

Cypress Barrio Reunion, 2007.

At a 2007 gathering of the Cypress Barrio Reunion in Orange, California,

a former El Modena Barrio resident and city of Orange Councilman

laughingly said, I had never

tasted a peanut butter and jelly sandwich until the schools were

desegregated. hen

he,, Fred Barrera, added: My white

classmates never tasted a burrito until then too.

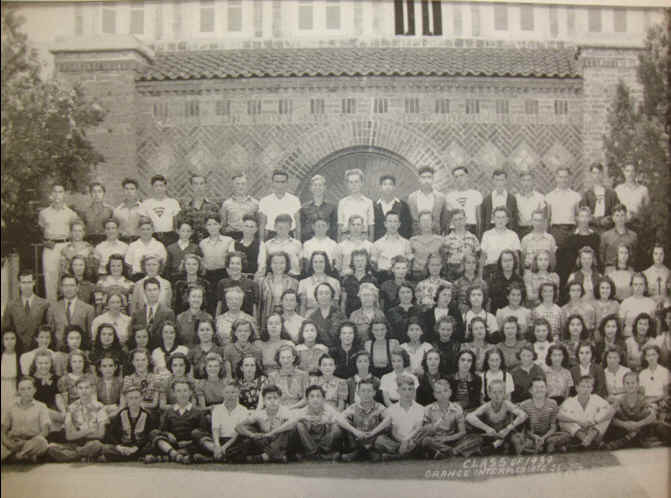

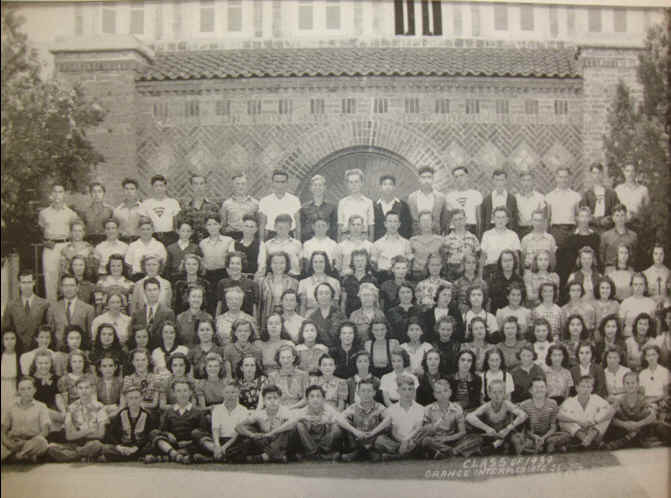

8th Grade 1939 Orange CA No. Glassell St Fred Barrera

Top row #4 from Left

Courtesy Shades of Orange

Also at the reunion

was an Orange resident who remarked how upset she felt when as a student

at UCLA she learned about the residential segregation of Mexicans.

She says, At first I felt

angry at the situation and at my family for never telling me about it.

But the more I learned about it, I discovered it was a way of

life back then. It helped

preserve our culture and keep our community close (Bacalso, June 24,

2007, in www.SomosPrimos.com).

Sixty-three years

earlier in 1944, the emotions of Soledad “Chole” Vidaurri were of a

different mix when she interacted with a teacher at the All Anglo

Westminster Main School (aka the Seventeenth Street School).

To repeat, Soledad,

the sister of Gonzalo Méndez Sr, had taken her two girls (Virginia and

Alice) and the three children belonging to her brother to register them

for classes that fateful September of ‘44. (Edward Vidaurri was sick;

He stayed home.)

The

Frank and Soledad Vidaurri family lived with the Gonzalo and Felícitas

family on a ranch in Westminster, a sleepy agricultural town of about

2,500 seven miles south of Santa Ana, CA. Gonzalo was leasing the rancho

from the Munemitsu family who was interned in Poston, Arizona. Frank

served as the patrón or mayordomo on the ranch running the farm machinery and supervising

the workers (Phone interviews with Alice Vidaurri Anaya, December 14,

2012, and Gonzalo Jr, January 08, 2012).

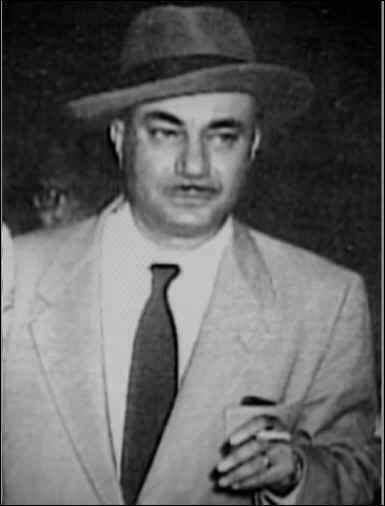

Soledad “Sally” Vidaurri ca. 1940s

Alice Vidaurri Anaya recalls that her mama,

Soledad, crocheted us yellow

dresses with ribbon-- really spiffy. She

and Virginia (age 11) were ready to spend their full day of school as

they carried their sack lunches with peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

During

our interview, Alice, who at the time was 10 years old, describes that

encounter by interspersing English and Spanish.

--We

went up them [auditorium] steps to register, really happy.

En ’44, yo ya tenía 10 [años] / In

’44, I was already 10 years old.

-- The teacher at the table looked at my mom and

said, ‘Mrs Vidaurri, your children can come here, but the other

children have to go to Hoover.’

--

Mom was in shock and said, ‘Could

you repeat that, please!’

--

Your name is Vidaurri but their

name is Méndez.

The

teacher could very well have answered by saying,

Mrs.

Vidaurri, your children are white. The Méndez

children, on the other hand, are dark-skinned and have a Mexican last

name. Therefore you have to register them at the Mexican Hoover School.

What follows, for the sake of comparison, is what Soledad Vidaurri,

Alice’s mother, told Alfred Zúñiga about her encounter with the

teacher at the White Westminster School (interview of 1974, in McCormick

& Ayala, 2007, p. 33; Title of article, “Felícita

‘La Prieta’ Méndez (1916-1998) and the End of the Latino School

Segregation in California”):

--Cuando

yo fui a llevar a mis hijos y a los hijos de mi hermano Gonzalo Méndez,

¡qué mal me sentí! / When I went to take my children and the children

of my brother Gonzalo Méndez, how awful I felt!

--Qué

pasó en este incidente que platica usted?/ What happened in this

incident that you are talking about?

--Tan

pronto como me dijo ella que ella aceptaba a los míos porque eran

belchis o Americanos, o qué eran, o de otra raza, le dije que yo, ¡que

no! Me dijo, ‘Yo te puedo reportar.’ Le dije, ‘Tú? Tú no me vas a

reportar a mí. ¡Yo te voy a reportar a ti!’

As

soon as she told me that she accepted mine because they were Belgians,

or Americans, or whatever they were, or from another race, I said, ‘No

way!’ She told me,‘I am going to report you.’ I said, ‘You? You

are not going to report me. I am going to report you!’

--No. Yo rehusé. Eso fue lueguito. No crea usted que yo tuve que ir

al rancho a decirle a mi hermano! Inmediatamente rehusé yo a la maestra

y le dije, ‘My kids, no van a tu escuela. Si los de mi hermano no van,

los míos no van.’ Somos de ese carácter. Y soy así. Entonces ya me

fui. Y yo me regresé pa’l rancho.

No, I refused. That was right away. Wouldn’t

you know that I had to go to the ranch to tell my brother! I immediately

refused the teacher[‘s offer], and I told her, ‘My kids, they are

not going to your school. If those of my brother aren’t going, mine

aren’t going either! We are made of that character. And I’m like

that. Then I got going. And I returned to the ranch (]).

Felícitas Méndez remembers the episode this way (interview by

Alfred Zúñiga, December 1974):

--La directora del plantel dijo hace 50 años a la señora Vidaurri, cuyos

hijos son hispanos blancos, de cabello claro, que no había problema en

matricular en la escuela a sus tres hijos, pero a los niños Méndez,

igual de prietos que yo [recuerda señalando la piel, doña Felícitas],

no podia inscribirnos. Pues ellos

tendrían que matricularse en la escuela Hoover la escuela Mexicana, a

donde se enviaba a los niños latinos del pueblo de Westminstter en esos

años (McCormick & Ayala, p. 33; Arrítola, 1995, p. 3).

--Fifty years ago the principal of the school told Mrs. Vidaurri, whose

children were white complexioned and had light colored hair, that there

was no problem in registering her kids at the school, but the Méndez

children who were dark the same as I, [doña Felicitas point to her

skin], she couldn’t register them [here]. Well they would have to

register them at the Mexican Hoover School, where the Latin kids from

the Westminster barrio were taken in those years.

(McCormick & Ayala, p. 24).

Public Schools’ Categorization of Mexican Students.

When it came to categorizing students, it was critical that school

officials know a student’s surname and/or their physical appearance.

Was the student dark? Did s/he have a Hispanic last name? Okay,

they go to the Mexican school.

Thus, for example,

Frank A Henderson, the Santa Ana Superintendent of Schools, testified in

court during the hearings of the Méndez

v. Westminster trial that in the matter of assigning students to a

given school, they classified them by looking

at their names to see if they were of Mexican extraction (Petitioners’

Opening Brief, September 29, 1945, Para IV).

Hoover

School

Westminster CA 1944

Alice Vidaurri

10 Years Old

BOTTOM:

Bobby Díaz; Robert “Beto” Vega; Lupe Castillo; Joe Hernández;

Albert “Calvo” Acosta; Silvestre “Chivete” Mendoza; George

Ledesma; Meño Arganda.

MIDDLE: Felipa “Lipa: Mendoza; Nacha Caudillo;

Margaret Mendoza; Francis Medina; (?)

Ponce; Julia Palomino; Jovita,

“Jovie” Pérez; Alice Vidaurri

TOP: Alice Tarín; Sally González; Josie Palomino;

Stella de la Cruz(?); Tillie Rosales; Ramona “Ronnie” Rivera; Gloria,

Cruz; Gloria Tarín’ Isabel Varela; Last one unknown

Alice said she was

stunned and confused by what she heard. She had lived in San Diego and

other cities, had gone to school with persons of different ethnic

backgrounds, and never before encountered such a disquieting

circumstance. Había de todo, she explained. / They

were of all kinds [ethnic backgrounds].

Alice continued,

--Mom kept her composure and said, ‘If my nephews and niece can’t

come, then, no. . . ! How can they go to the Hoover School when our two

related families live at the same address and reside in the Westminster

Main School district?’

The practice of

Anglo boards of education in Orange County of segregating Mexican

heritage students rested on a litany of unfounded racially based

beliefs. One, tied to

knowledge of English, alleged that Mexican students lacked proficiency

in English and that they had a bilingual

handicap. Another

opinion held that because Mexicans were an alien and immoral race, they

had to be segregated for the moral good of white society.

Other discriminatory

attitudes and practices were revealed during the Méndez et al. vs. Westminster et al. trial in 1945.

For example, Anglo professional educators stated that Mexicans

were dirty; that they didn’t

know the Anglo American culture and needed to be Americanized;

that they couldn’t compete with Anglo classmates.

Yet another was that they were immoral.

A key witness for

the defense, James L Kent, the Superintendent of the Garden Grove School

District, wrote an M.A. thesis in education in 1941 at the University of

Oregon. Among other opinions, he held that Mexican children could not

compete with their white peers because of malnutrition and related

issues. He writes,

They

are malnourished] because of the fact that their natural dishes consist

of tortilias [sic], a greasy mixture, or enchiladas and beans. These

foods, although giving sustenance to the body, do not provide a well

balanced diet. Sick in mind and in body, the Mexican child finds that he

is no match in intelligenge

[sic] or in desire, for his white brother in his school work” (pp 22-23).

Attorney

Marcus obtained Kent’s thesis and had it admitted as evidence over the

objection of the defendant counsel. In studying the thesis Marcus found

that Kent believed that Mexicans were a race. With Kent on the witness

stand, Marcus asked, “Is it not a fact that you believe that the

Mexican is not of the white race?” His reply: “I believe he is an

American. I don’t believe he is of the white race.” Apparently Kent

changed his mind about Mexicans not being white. He said he now believed

that a Mexican is of the “white” race, “That is one of the reasons

why they are segregated (R. Tr. pp. 119, 129, 124).”

Here

is a brief transcript of an exchange between David C Marcus, lawyer for

the plaintiffs, and James L Kent during the hearings of Méndez v. Westminster:

David

C Marcus

Marcus Mr

Kent, with respect to educational ability, it is your opinion that the

Mexican children are inferior to the white children?

Kent

In their ability, yes.

Marcus

What percentage, in your opinion, is inferior?

Kent

In what?

Marcus

In scholastic ability.

Kent

75 per cent.

Marcus [I]n what other respects are the children of Mexican descent

inferior to the other children in your district

Kent In

their economic outlook, in their clothing, their ability to take part in

the activities of school.

It

turns out that the 7th grade class at the Mexican Lincoln

School in El Modeno outperformed their White counterparts at the Anglo

Roosevelt School in standardized achievement tests (Wollenberg, 1976, p.

128).

Apparently

Kent based his opinion of the “inferior educational ability” of

Mexican children on a study by B. F. Haught. In 1931 Haught found that

Mexican children’s intelligence quotient was 79 compared with 100, the

average score for the average Anglo counterpart (Gonzalez, 72; Donato,

p. 27; see p. 88 of Kent’s thesis for title of article by B. F. Haught).

In

Community of El Modena, CA: White Roosevelt School (left) & Mexican

Lincoln School (right) ca. 1940

A

noted professor of education who earned his doctorate at the University

of California, George I Sánchez (1906-1972) argued that in order to

comprehend the results of IQ tests standardized on white middle class

students, one had to consider the differences in class, language and

ethnic differences (García, 1989, pp 253-267) in order to properly

interpret results.

In

Literacy and Language Diversity in

the United States (1996), Terrence Wiley states that “intelligence

tests have long been criticized for implicit language and cultural

biases.” He adds that

standards upon which both functional literacy

and academic achievement are based typically reflect the norms of

middle-class, monolingual, English speaking populations. . . .[that]

become imposed on the population as a whole with the result, too often,

that those who fail to meet these levels are stigmatized.

The

first IQ test was developed in France by Alfred Binet in 1905. The

American version of the French Binet intelligence test was published as

the “Stanford-Binet” test in 1916 (Kamin, 19774, p. 6).

The

American psychologist Lewis Terman was an early advocate of the efficacy

of IQ testing. Terman, a Stanford University professor, favored

sterilization of those found to have inferior intelligence on IQ tests.

These were classified as feeble-minded. Others like Thorndike believed

that the less intelligent were morally inferior as well (Wiley, 1996, p.

60). In 1916 Terman wrote that the 70-80 range of intelligence

is very, very common among Spanish-Indian and

Mexican families of the Southwest and among negroes. Their dullness

seems to be racial. . . [When experimental methods are done] the writer

predicts there will be discovered enormously significant racial

differences in general intelligence, differences which cannot be wiped

out by any scheme of mental culture.

Children of this group should be segregated in

special classes. . . They cannot master abstractions, but they can often

be made efficient workers. . . . they should not be allowed to

reproduce, although from a eugenic point of view they constitute a grave

problem because of their unusually prolific breeding (in Kamin,

p. 6; also see González, Chicano

Education in the Era of Segregation, pp 62-76.)

Interestingly

enough, during the preliminary hearings, the two defense lawyers

accepted the premise that Mexicans were legally white. And just as

interesting, students of Japanese ancestry were also considered white.

Yet Japanese and Portuguese students were admitted to the Anglo grammar

school by the Westminster School trustees--not Mexicans. One can surmise

why this happened. It is not far fetched to say that it was because the

Japanese and Portuguese were farmers, and as such, persons of

importance.

Alice

continued her sad story—

--Nos recogió / She

gathered us together, got us in the car like a mother hen gathers her

chicks, and when we returned to the [Munemitsu] ranch, Gonzalo asked

mama, --Qué estás haciendo con los niños contigo? / What are you doing

[here] with the children?

When Soledad,

Alice’s mother, told the terrible news, Gonzalo simply said, Hermana, tú sabes que yo tengo el dinero y tú haz lo que quieras hacer.

/ Sister, you know that I have

the money. . . You do what you want to do.

--So she took us to Hoover.

Virginia

“Ginger” & Eward Vidaurri @ Hoover School

Combination Class Picture 1944

Front

L-R NN, #2Angélica Mendoza, Virginia Vidaurri, Gloria Carrillo, Lecha

Ponce, Gregoria Medina, Mini Ledesma, Catalina

Rivera

Middle

#1Edward Vidaurri, María “Baudelia” Vela, María Herrera, NN, Sal

“Chavo” Vela, Johnny Pérez

Back

Frank Acosta, NN,

Nadine González, NN, Mrs Stacey, “Red” Varela, Alex Vigil,

Lito Hernández,

Willie Vega, Augi Huntes,

NN

We

learn from testimony in the Méndez

case that the Hoover School had 152 students taught by eight American

teachers. In Superintendent

Kent’s opinion, They are the

best teachers we have, we feel. He stated that seven of the teachers

had been assigned there 10-12 years; the eighth teacher, eight years.

I

asked Alice to describe the playground. --It had a wall where we bounced a ball. We’d bring our own ball.

Era pura tierra / It was all dirt.

--Books? I don’t know where they came from but they were written

in. Mom would say, ‘Ignore

that. Write in another space.’

--Never [had] new crayons. No eran nuevos / They weren’t new. They

were all broken. Could it be they were brought from the Seventeenth

Street School?

The

All-Mexican Hoover School in the Middle of the Colonia ca. 1930s

In

Background is a Covered Structure. Building on Left Housed Grades,

K-1-2-3

Hoover Dedicated in 1929 as an Americanization School

By

all appearances, Hoover School was not the “terrible two-room shack”

with menacing flies from the dairy across the street as has been

described in interviews. But

it is a distant second when compared to the beautiful architecture,

lovely evergreen trees and manicured lawn of the Seventeenth Street

School that became All White in 1929, and Hoover became All-Mexican.

This is when the Board of Education took the Mexican students out of

Seventeenth and sent them to Hoover to “Americanize”

them.

At

the September 19, 1929 meeting of the Westminster School Board of

Education, trustees talked about installing a lawn at Hoover. The

minutes read,

The question of a lawn along parking at the Main

School and in front of the Mexican School was discussed but definite

action was postponed.

One

bright sunny morning in 1944/45 there was lots of excitement and

commotion in the Hoover play yard. Classmates were running toward the

west side of the campus toward the street.

I followed along. I

asked Alice if she recalled what was happening.

She

tells the story this way.

Isabel Vega lost a paper she was carrying. A

gust of wind carried it to the fence across the street from the west

campus. As she reached for it, her hand got caught on an electrified low

voltage wire. This wire was meant to keep a dairyman’s cows from

leaving their pasture. Frank “Red” Varela told someone [Mike González]

to tell the farmer to turn off the current.

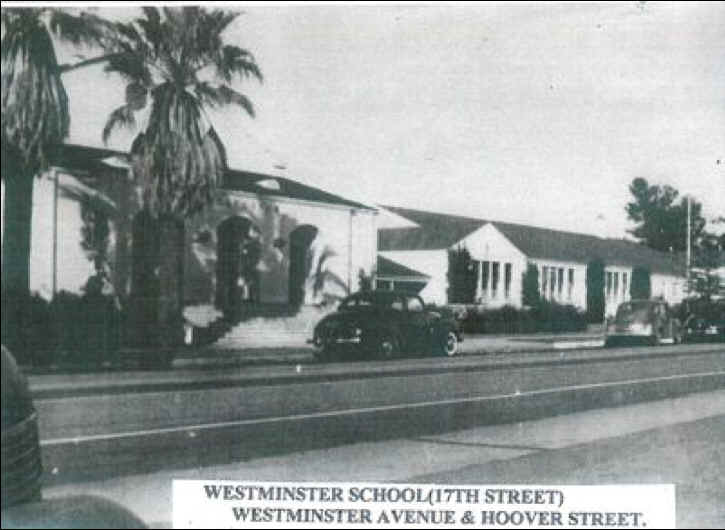

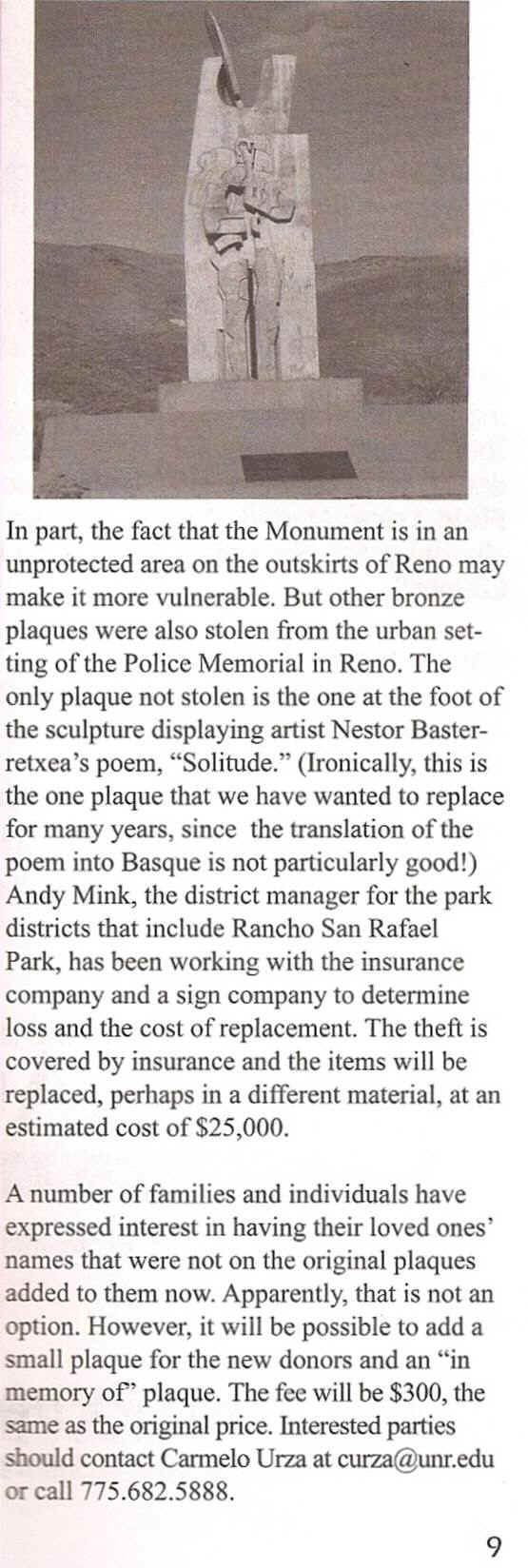

Beautifully Landscaped School Replaced the One Severely Damaged by

the 1933 Long Beach Earthquake

Alice

Vidaurri Recalls Walking Up “Them Steps” to

Register For Class in 1944

Alice

spoke about being disciplined. She admitted, --I got hit quite a bit. I was outspoken. They’d tell us not to

speak en español. But we’d forget because we’d speak Spanish at

home, and from home to school se te olvida (you forget) so I got hit

with a ruler. [I knew I’d] get hit again if we told our parents what

happened at school.

-- ¡Me las comía!,” Alice confided. / I would just take it

(being hit).

-- We were taught that our teacher was like our mom. The teacher

would find one of the students to snitch on you

(snitching acknowledged by another interviewee).

In

an in-depth study of the K-12 education of Mexican Americans in the

Southwest, Grebler et al. (1970) reported on White educators’ reasons

why they prohibited the use of Spanish in the Southwest (p. 175).

English is the

national language and must be learned.

Bilingualism

is mentally confusing.

The

Spanish spoken in the Southwest is a substandard dialect.

Teachers

do not understand Spanish.

Grebler

et al. hypothesize that

the rejection of Spanish may largely reflect the

feeling that the Spanish-speaking child represents a threat to Anglo

school authority and control; teachers do not know what Mexican

Americans are saying—are they disrespectful or impudent, using foul

language, urging their peers to riot and revolt? Speaking Spanish may be

seen as a subversive activity, an undeciphered code reflecting hostility

and plotting against school authorities” (p. 175)

In

the September 13, 1929 minutes of the Westminster School Board, the

Trustees speak of Hoover as the Mexican

School (author’s italics). At this meeting the trustees voted to

discontinue “present Janitor

[sic] services at the Mexican School.”

The

following month, at the October 13 meeting, a Westminster School trustee

motioned to have “Manual

Training and Domestic Science installed as cheaply as possible.”

The

motion carried. Trustees also approved the following warrants for the

Hoover School teacher Ethel Paulk (known as

Mrs Polka by former barrio students)

$130.00, and Mrs. de la Cruz, janitor, $13.00. Clyde Day took the

minutes as the Clerk of the Board.

The

attitude and policies of the Westminster School Board of Education

toward the education of Mexican heritage students was consistent with

that of other boards in Orange County and in the Southwest. They

reasoned that since the intelligence of Mexican was inferior, they could

be housed in inferior buildings. González puts it this way,

IQ theory placed the Mexican community at a

particular disadvantage in that it barred its educational advancement,

justified its segregation, legitimized its political domination. . . .

and contributed in no small measure to an education that stressed

preparation for semiskilled and unskilled labor (p. 66).

In

the nearby Santa Ana schools, the trustees also made references to the

Mexican School. This is how the segregated schools in Orange County

were known as. School

trustees used this nomenclature to identify the class of students they

were segregating. The difference in Santa Ana is that they had three

all-Mexican schools whereas Westminster, El Modena and Garden Grove had

one each.

Simon

Ludwig Treff (Master’s thesis, 1934) reported that over a quarter of

the roughly 16,000 students in Orange County were Mexicans or Mexican

Americans. At this time there were 15 all-Mexican elementary schools (in

Wollenberg, 1976, p. 116).

Alice

said that a third sister, Olivia, was born to the Vidaurris in 1946

shortly after the family left for the San Joaquin Valley in central

California. They nicknamed her Libby.

--She knows all the history. Mama spoke of our

history always.

As

for her part in the family’s legacy, Alice commented that sometimes

Libby speaks of herself in the third person:

--Olivia, you’re never spoken of in our

history. [You’re] a left

wheel here!

Alice

explains that the Vidaurris moved from Westminster on account of her

mom’s asthmatic condition. Her doctor said she needed to find a

warmer, drier climate.

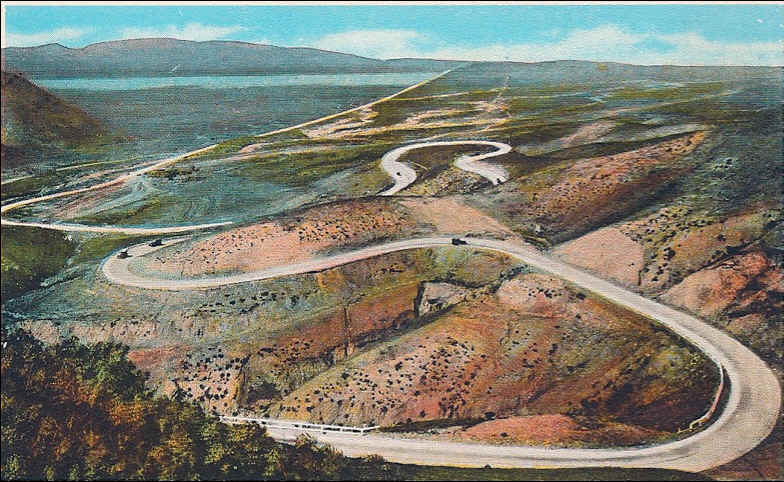

--Her

lungs opened as soon as we got to [the town of] Gorman on the Ridge

Route” (the Grapevine, now I-5).

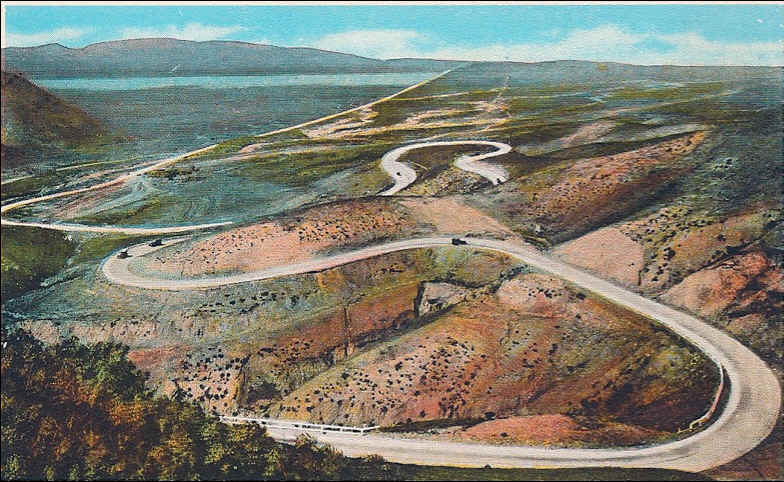

The Old Ridge Route Connecting Bakersfield & Los Angeles ca. 1930s

Gorman is South from this Point About 10 Miles From Bakersfield.

Looking North Toward Bakersfield

Master’s

theses on the education and Americanization of Mexican students were

written in the 1930s by students of Dr Emory S Bogardus of the

University of California. Betty Gould’s 1932 Master’s thesis was

titled, “Methods of Teaching Mexicans.”

For

her data on the methods of teaching Mexicans, Gould observed Anglo

teachers in the Mexican schools in Stanton, Delhi, Magnolia, and the

Herbert Hoover school in Westminster, all in Orange County (pp 9-10).

She tells us she spent nearly 1,500 minutes interviewing 30 teachers and

principals in Los Angeles and Orange Counties (pp 8-9).

Although

Gould’s thesis is not as hostile or as racist as Kent’s thesis,

nevertheless, it carries stereotypical impressions of Mexicans that curl

one’s hair. For example, she writes

The Mexican is naturally indolent, and his

tendency to “never do today what can be put off until some other

time” is one of the outstanding problems with which the school is

confronted (p. 2).

As a general rule, the parents lack any desire

for education (p.2).

Mexican labor is seasonal, and the occupation of

children of school age presents a serious problem to the school. During

walnut season many Mexican schools in southern California have to be

dismissed because the attendance is so irregular. The writer was pleased

to learn that of late, schools are beginning to be established close to

the worker’s camps, and the children are forced to attend these

“migratory” schools at least part of the day (p. 2).

Prize fighting is more popular with Mexicans

than football. Their athletes are few, because they can not stand

punishment, and dislike to be beaten (pp 2-3).

The Mexican children of laboring parents are,

for the most part, handicapped by having decidedly inferior mental

equipment.

They can do a greater amount of routine work

than the American child, and seem to enjoy it (p. 3).

In Chicano Education in the Era of Segregation, Dr Gil González

examined 46 theses and dissertations. About these he writes,

The Americanization literature. . . .was not

uniformly negative in intent. The intent seemed more often patronizing

than negative, more insensitive than malicious,” (p. 38).

He states that UCLA

and USC created special courses for the teaching of Mexican students.

Some school districts like Santa Ana, Los Angeles and Long Beach set up

bureaus called Department of Immigrant Education or Department of

Americanization (p. 38).

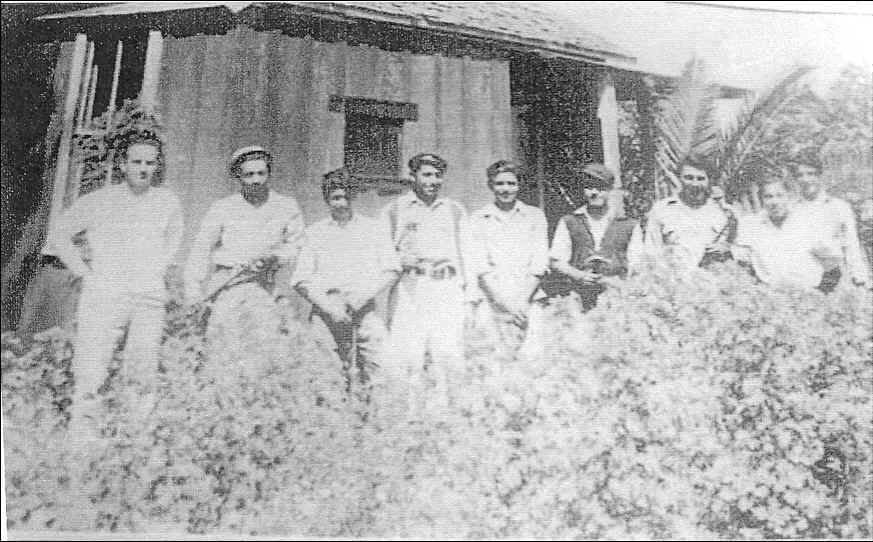

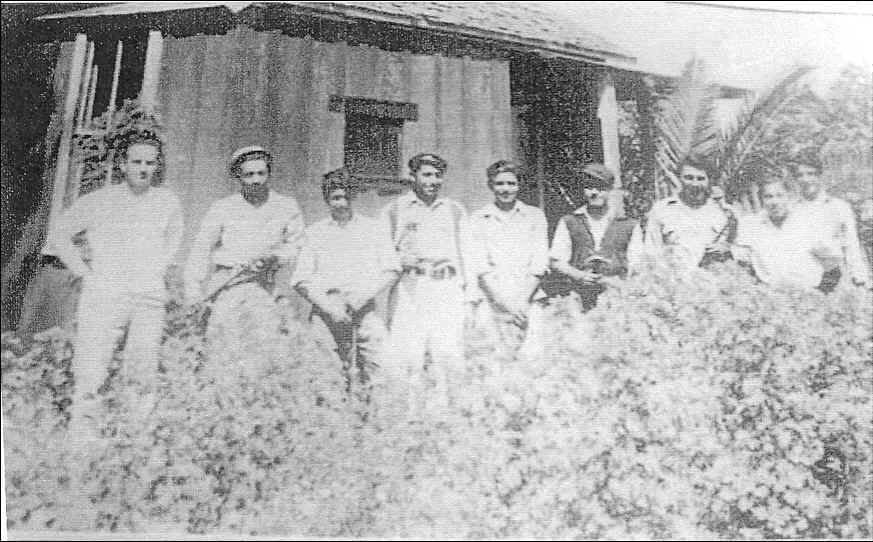

Westminster

Barrio Boys’

Club House

SE Corner Main & Olive Streets

Ca. 1940

Mr

Miceli on Left

Adán Méndez (Andy Vásquez’ Friend) Far Right

The

Mexican American students in the above picture lived in the Westminster

barrio and were students at the Hoover School. Mr Miceli (left) was

their teacher. Noticeable are tools in students’ hands. They look like

high school age, 15-17. The Club House was in the middle of the barrio

on Main Street about a block and a half north of the Hoover School. My

brother Salvador (b. 1931) believes the purpose of the Club House was to

learn a trade; that it was in use for about 10 years (note of January

24, 2012).

A

principal of an east Los Angeles high school whose student body was

predominantly Mexican American reported that not more than 2% of

Mexicans went to college and that 50% dropped out. That being the case,

educators reasoned that these students should receive vocational

training earlier at least in the elementary grades. Many Mexican

students received up to 12 years of vocational coursework (González,

1999, p. 67).

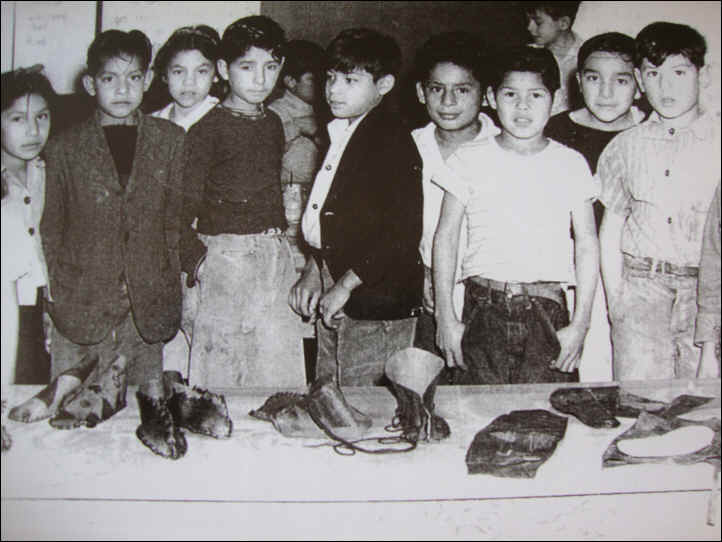

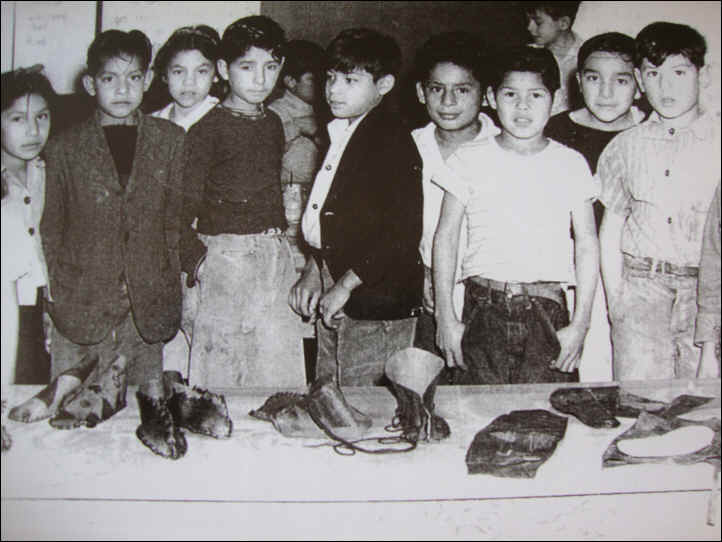

Manual

Arts Handiwork of Logan Mexican School Santa Ana CA ca. 1940s

Schools

used intelligence tests (IQs) to sort (track) the children. Students

scoring high were placed in challenging academic or college preparatory

classes. Those scoring lower were put in the average or below average

tracks. The lot of the average and below average students was to be

assigned vocational education classes to learn the value of hard work,

the moral values of the dominant society, and discipline (Oakes, pp.

30-31).

While

educators in the east coast devised a diversified curricula to meet the

perceived schooling needs of the millions of immigrants from eastern and

southern Europe, 1890s-1920s (Oakes, pp 15-35), educators in the

Southwest applied similar ideas and structures for students of Mexican

heritage (González, pp 87-88).

Gonzáles

(1999) states that at the turn of the century White middle class

educators adhered to false beliefs of social Darwinism, the driving

force behind the creation of differentiated curricula (pp 36-38).

They held that

Children of various social classes, those from

native-born and long-established families and those of recent

immigrants, differed greatly in fundamental ways. Children of the

affluent were considered by school people to be abstract thinkers, head

minded, and oriented toward literary. Those of the lower classes and the

newly immigrated were considered laggards, ne’er-do-wells, hand

minded, and socially inefficient, ignorant, prejudiced, and highly

excitable (Oakes, p. 35).

In

The Mismeasure of Man (1981),

Gould takes a long look at the business of social scientists including

the pioneers of IQ tests. In his Introduction, he writes

Science. . . . is a socially embedded activity.

It progresses by hunch, vision, and intuition. . . .Facts are not pure

and unsullied bits of information; culture also influences what we see

and how we see it. Theories, moreover, are not inexorable inductions

from facts. The most creative theories are often imaginative visions

imposed upon facts; the source of imagination is also strongly cultural

(pp. 21-22).

Gould

proposes that a fallacy of intelligence testing is the belief that one

can reify or “convert abstract

concepts into entities”(things). Once the concept of intelligence

is reified, Gould continues, social scientists create procedures to

quantify it, that is, assign it objective numbers.

Then

he states that when intelligence is reduced to a “single entity” and its location is found in the brain, and a “number

[is found] “for each individual,” the numbers are then used to

rank people “in a single series of worthiness, invariably to find that

oppressed and disadvantaged groups—races, classes, or sexes—are

innately inferior and deserve their status” (pp 24-25). There

is much history behind intelligence testing to merit dissertations.

Kids

Dressed as Charros (Cowboys) in a Mexican Home off Olive St Wsmtr Barrio

ca. 1940s

Dr Jane Mercer of the University of California, Riverside

published a study in 1973 that showed how Mexican American children were

overrepresented in classes for the mildly mentally retarded (EMRs) (Rueda,

p. 256, in Valencia, 1991, p. 255). Her data showed that whereas Mexican

children constituted “9.5% of the population in the small California community which she

studied, they comprised 32% of those labeled and placed in classes for

the mentally retarded” (Rueda, p. 256).

I

return to the early part of this story, to the 2007 gathering of the

Cypress Barrio Reunion in Orange, and to the reaction of the young lady

who attended UCLA where she learned about the segregation of Mexicans in

Southern California.

As

she reflected on this seldom told history of segregation of Mexicans in

Southern California, she saw a positive side when she said, But the more I learned about it, I discovered it

was a way of life back then. It

helped preserve our culture and keep our community close..

Undoubtedly

so. Life “back then” had

its light and dark shadows of light. But no matter how one looks back at

it, segregation oppressed Mexican Americans economically, socially,

culturally, linguistically, psychologically, and spiritually and was not

good for White society either.

By

the time I came of age, 1940s-1960s, relations with Anglo Americans had

turned for the better with respect to jobs, housing, recreation, and

education. I am most grateful for all life’s propitious opportunities

that have come my way [including getting to know Alice Vidaurri Anaya, la

Pistolera de Bakersfield

as an acquaintance called her]!

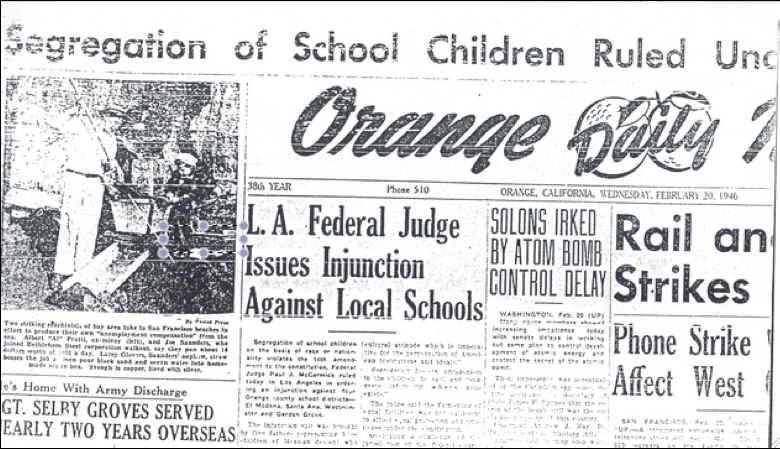

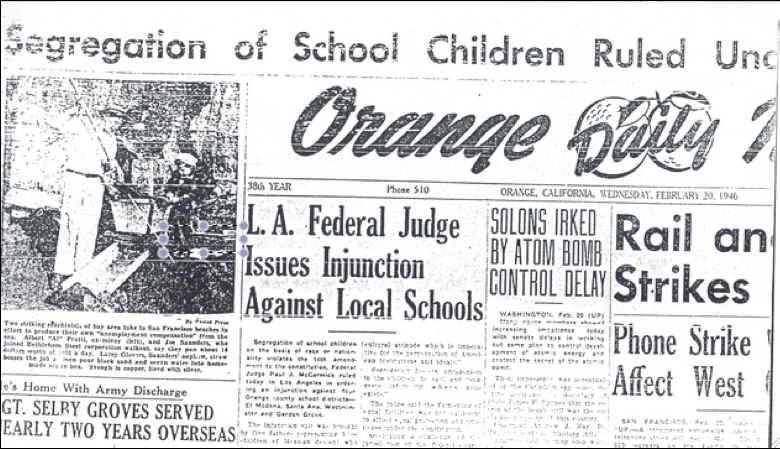

Orange

Daily News

Orange CA Feb 20 1946 “Segregation of School Children Ruled

Unconstitutional”

Courtesy

Christopher James Arriola

By

being curious and questioning critically, eventually one gets to know

more about the long winding roads taken by 100,000s of Mexican American

men and women (who at the turn of the 20th century emigrated

from Mexico into California for a better life). One question inevitably

leads to more. The UCLA student might look deeper into

“I discovered it was a way of life back then. It helped preserve our

culture and keep our community close.”

To

the UCLA student and others, I recommend these books and topics that

follow. They might start by reading North

from Mexico (McWilliams); The

Mexican Americans: An Awakening Minority (Servín); Latinos

United (Trueba); Unwanted

Mexican Americans in the Great Depression (Hoffman); East Los Angeles: History of a Barrio (Romo); Man’s Search for Meaning (Frankl); Chicano Education in the Era of Segregation (González); The

Mismeasure of Man (Gould); The

Chicano (Hundley). . .

Pacific Electric

Interurban Trolley (Big Red Car) Strike of 1903 in Los Angeles led by docile Mexicans

Mexican workers

waged many agricultural strikes throughout California, 1900s-1930s

1935 & 1936 Citrus Strikes in Orange County by Mexican Americans

Mexican families

following the crop into Utah, Washington, Oregon, Wyoming, Nebraska,

Kansas, Minnesota, Chicago, Indiana, and Pennsylvania in the 1900s

Mexican students who dropped out of school because they were over

age

Cooperative efforts

of Anglos and Mexicans who contributed to the ultimate success of the Méndez

case (and other civil rights lawsuits)

Underrepresentation

to this day of Mexicans in business and the professions, and holding

advanced degrees

Untold numbers of

persons of Mexican heritage who lament they were forced to drop out of

school by because their father’s wages were too low. . .

Forced deportation

“repatriation” of 500,000 – 600,000 Mexicans from Southern

California and the Midwest to Mexico, 1929-1939

The continued school

segregation of Mexican students through tracking: High Honors, Honors. .

.

How Angel Varela Sr

came out of the Westminster barrio, attended integrated public schools

in Huntington Beach, started a small business that grew to become Ace

Tube Bending Company in Aliso Viejo, CA, a supplier of precision

machined parts for Boeing, Northrup Grumman, Honeywell, Lockheed Martin,

and other major corporations.

Ace

Tube Bending Corporation / Angel Varela / Aliso Viejo / 2011

Somewhere

in G J Rentier’s work , History: Its Purpose and Method, I came

across statements about the value of history. Here are some.

History is not simply about learning facts.

History is a form of memory, and memory is a foundation of

self-identity.

A people who do not know their history do not

know themselves. They are a people doomed to repeat the mistakes of

their past because they cannot see what the present – which always

flowers out of the past--requires of them.

There is a practical past . . . from which the

present has grown, which has been influenced in deciding the present and

future fortunes of man.

The historian knows the past by re-enacting it

in his own mind. This is done by thinking the thoughts of men who lived

in the past.

[I]ndifference to our Christian past contributes

to indifference about defending our values and institutions in the

present (ZENIT, January 2011).

And

from Viktor E Frankl: we had to

teach the despairing men, that it did not really matter what we expected

from life, but rather what life expected from us, p. 98.

Hoover

School ca 1938

Combination Class Grades 5, 6, 7 & 8

Mr

Miceli Teacher/Principal, Upper Grades

Bottom

L-R: Daniel Limas, Andrew Rivera, Jessie Limas, Ralph Cervantes, Manuel

Rivera, Peter Jackson,

Ignacio “Glida” Medina, Adán Méndez, Raymunda Poyorena,

Dolores Vela, Annie Varela, Julia Rivera, Angelina

Pérez?

Middle:

Julia Vela, Mini Díaz, Aurelia González, Lola Palomino Rivera, Irene Pérez,

Virginia López, Lola Rivera,

Jenny Palomino, Benigna “Bennie” Medina, Rosina Mendoza

Top:

Mr. Miceli, Titino Castillo(?), Julio Méndez, Francisco “Kiko”

Felix, Joe Arganda, Lalo Cruz, Victor Ramírez, Raymond Bermúdez,

Alesio Méndez, Ofelia Poyorena, Vangie Díaz, Mary Vega, Evelyn Peña,

Pauline Rivera, Anita Hernández

The

foregoing quotes bring to mind the courage of humble bilingual and

bicultural Mexican American parents of the Westminster barrio. While

they held meetings and sat around neighbors’ kitchen tables to discuss

how to eliminate the social scars of school segregation, other meetings

were taking place in the El Modena barrio and the Santa Ana barrios of

Delhi, Logan and Artesia.

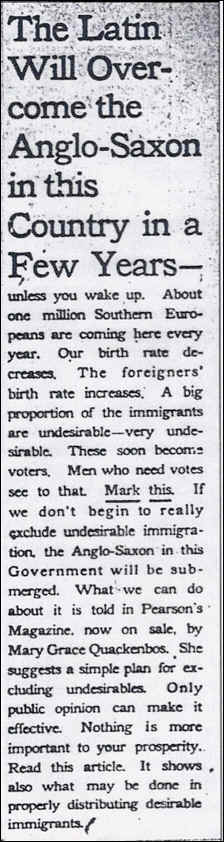

El Paso Times Jan 03, 1911

The Westminster Board of Education Meeting, September 19, 1944. Six months before the five Mexican plaintiff

families filed their class action lawsuit, representatives from the

Latin American League of Voters (LALV) spoke on behalf of barrio

families at the September 19, 1944 meeting of the Westminster Board of

Education. LALV members present were Messrs. Cruz Barrios, Manuel Vega

Jr and Hector Tarango, all middle class residents of nearby Santa Ana.

Gonzalo

Méndez recalled that meeting in his testimony of July 9, 1945.

I asked Mr [Richard] Harris [Superintendent],

that we were sent from our group that we had formed, and that me, and

Mrs. [Frank] Vidaurri, and Mr. and Mrs. [Dolores] Peña were chosen as

representatives or delegates to go and interview the School Board of

Education, and that our meeting had decided to ask Mr. [Cruz] Barrios

and Mr [Manuel] Vega to come and be present at the School Board of

Education from Santa Ana.

The first one to talk was Mr. Barrios. He

thought that it would be a very good idea to have the schools united,

that that would create a better democratic way of living among those

districts, as being segregated up to that certain extent. . .

And I think that Mr. Houlihan [Board President]

was the one who answered Mr. Barrios, and he said he was very much in

sympathy with the way he thought; that he thought it was a very nice or

good way to get at it.

And Mr. Vega talked after that, and he told Mr.

Richard Harris that he thought that the Mexican people were not, as in

other words, he put it as he named it, as dumb as lots of people thought

they were. He said, “In fact, I have very many friends that I went to

high school with who outsmarted the Anglo-Saxon races…”

. . . .So Mr Richard Harris said that he knew

some persons or some young boy, too, that he could – that he knew him

very well, that was a very smart Mexican boy, and that he thought that

Mr. Vega was right in that way. And Mr. Conrady [Board Secretary] did

not have much to say on that meeting. He favored all of the Mexican

children and the Americans should be united (Transcript in de la Torre

Aguirre, 2009, pp. 250-51).

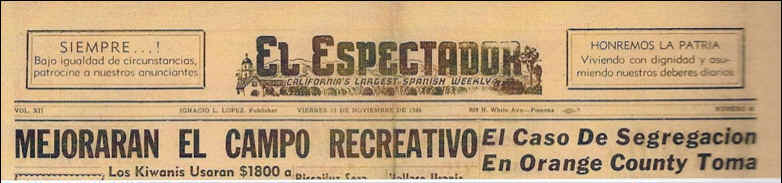

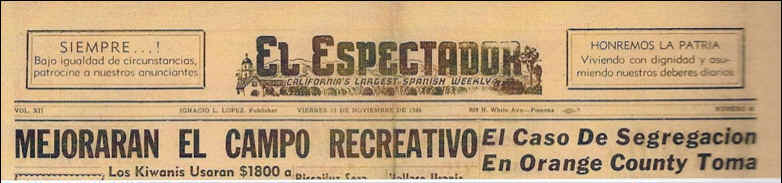

Spanish Speaking Newspaper Published Weekly by Ignacio L. López,

Pomona

El Caso De Segregación

En Orange County Toma Proporciones Nacionales /

The Segregation Case in Orange County Takes on National

Proportions December 15, 1946

At the Board of

Education meeting of September 19, 1944, the parents submitted petition

in a letter addressed to the Clerk (Board Secretary), Louis Conrady.

Thirty-seven (37) Westminster Mexican parents signed their signatures.

Here is the text of the letter (author’s bold italics).

Sept.

8, 1944

Dear

Sir:

We, the undersigned, parents, of whom about one-half are American

born, respectfully call to your attention to the fact that of the segregation

of American children of Mexican descent is being made at Westminster,

in that the American children of non-Mexican descent are made to attend

Westminster Grammar School on W. Seventeenth Street at Westminster, and

the American children of Mexican extraction are made to attend Hoover

School on Olive Street and Maple Street. Children from one district are

made to attend the school in the other district and

[W]e believe this

situation is not conducive to the best interests of the children nor

friendliness either among the children or their parents involved, nor

the eventual thorough Americanization of our children. It would

appear that there

is racial discrimination and we

do not believe there is any necessity for it

and would respectfully request that you make an investigation of this

matter and bring about an adjustment, doing

away with the segregation above referred to. Some of our

children are soldiers in the war, all

are American born and it does

not appear fair nor just that our children should be segregated as a

class.

Respectfully submitted,

Mr

Mrs. Gonzalo Mendez

Ernesto Peña

Mr

& Mrs Rufus Bermudez

Irineo Hernandez

Mr

& Mrs Juan B Bermudez

Mr & Mrs Perez

Mr

& Mrs Saturnino B Bermudez

Mrs Angelina Banuelos

Felix

Bermudez

Mr & Mrs Saucedo

Mr

Camilo Bermudez

Mr & Mrs Jose Rosales

Pablo

de la Cruz

Mr & Mrs Trinidad Vega

Guadalupe

Arganda

Augustin C Ledesma

Mr

& Mrs Vidaurri

Mr & Mrs Paul S. Cruz

Mr

& Mrs Estrada

Ralph Díaz

Juan

Reyna

Roy e Mendez

Reyes

C Ponce

Connie M. Acosta

Dolores

Mendez

Elvira Zapata

Thirty years after Judge McCormick ruled against the defendant

school districts, the Santa Ana

Register printed the article, “Murder Obscured 1946 OC Integration

Landmark.” The reporter asked the well- known OC historian, Jim

Sleeper, about the case. The reporter notes that Jim was a Santa Ana

High School student in ’46 and didn’t “remember a thing about

it.”

The staff writer, Stan Oftelie, reports Sleeper’s observations:

It

wasn’t a very big thing here. It had a bigger impact nationally. There

was no conspiracy to shush it up. It was just overshadowed. I don’t

believe there really was much interest in it. This was pretty much a

white spot. There were about a dozen or so Mexicans at the high school

and one or two Negroes.

He also recalled that there was no segregation at the Santa Ana

High; that there wasn’t much prejudice in the area (Santa Ana Register, August 22, 1946, pp. A1, A12).

The Mexican Parents Sentiments Reflected in McCormick’s 1946

Ruling. You can almost feel the sentiments of the parents (and their

attorney) echoed by Judge John McCormick when he found in favor of the

petitioners in his “Conclusions of the Court” (filed February 18,

1946).

Parents

. . .segregation of American children of Mexican descent is being made

at Westminster

. . .and [W]e believe this situation is not conducive to the best interests of the children

. . .nor friendliness either among the children or their parents

involved

. . .nor the eventual thorough Americanization of our children.

. .there is racial discrimination.

. .we do not believe there is

any necessity for it

McCormick

. . .“The equal protection of the laws”

pertaining to the public school system in California is not provided by

furnishing in separate schools the same technical facilities, text books

and courses of instruction to children of Mexican ancestry that are

available to the other public school children regardless of their

ancestry.

A paramount requisite in the American system of public education

is social equality. It must be open to all children by unified school

association regardless of lineage.

The evidence clearly shows that Spanish-speaking children are

retarded in learning English by lack of exposure to its use because of

segregation, and that commingling of the entire student body instills

and develops a common cultural attitude among the school children which

is imperative for the perpetuation of American institutions and ideals.

It is also

established by the record that the methods of segregation prevalent in

the defendant school districts foster antagonisms in the children and

suggest inferiority among them where none exists.

The record before us

shows a paradoxical situation concerning the segregation attitude of the

school authorities in the Westminster School District. There are two

elementary schools in this undivided area. Instruction is given pupils

in each school from kindergarten to the 8th grade, inclusive.

Westminster has 642

pupils, of which 628 are so-called English-speaking children, and 14

so-called Spanish-speaking pupils. The Hoover School is attended solely

by 152 children of Mexican descent.

Segregation of these

from the rest of the school population precipitated such vigorous

protests by residents of the district that the school board in January,

1944, recognizing the discriminatory results of segregation, resolved to

unite the two schools and thus abolish the objectionable practices which

had been operative in the district for a considerable period [since

1929].

A bond issue was

submitted to the electors to raise funds to defray the cost of

contemplated expenditures in the school consolidation. The bonds were

not voted and the record before us in this action reflects no execution

or carrying out of the official action of the board of trustees taken on

or about the 16th of January, 1944.

It thus appears that

there has been no abolishment of the traditional segregation practices

in this district pertaining to pupils of Mexican ancestry through the

gamut of elementary life. We have adverted to the unfair consequences of

such practices in the similarly situated El Modeno School District (BACM

Research, CD-ROM, 2009, pp 12-13).

Parents.

. .

and it does not appear

fair nor just that our children should be segregated as a class\

McCormick

The common segregation attitudes

and practices of the school authorities in the defendant school

districts in Orange County pertain solely to children of Mexican

ancestry and parentage. They are singled out as a class for segregation.

Not only is such method of public school administration contrary to the

general requirements of the school laws of the State, but we think it

indicates an official school policy that is antagonistic policy in

principle to Sections 16004 and 16005 of the Education Code of the

State.

It is now, in

conformity with the findings of fact and conclusions, ordered, adjudged

and decreed: That this action by plaintiffs is a representative class

action on behalf of themselves and of all persons of Latin and Mexican

descent and that the action has been properly brought as such class

action pursuant to law (“Judgment and Injunction,” March 21, 1946,

p. 2).

Parents.

. .

bring about an adjustment,

doing away with the segregation

McCormick

We conclude by holding that the allegations of the complaint (Petition)

have been established sufficiently to justify injunctive relief against

all defendants, restraining further discriminatory practices against the

pupils of Mexican descent in the public schools of defendant school

districts (“Judgment and Injunction,” March 21, 1946, pp

2-3).

And

it is further ordered, adjudged and decreed that the defendants and each

of them are hereby permanently restrained and enjoined from segregating

persons and pupils in the elementary schools of the defendant school

districts, respectively, of Latin or Mexican descent in separate schools

within the respective school districts of the defendants and each of

them within the City of Santa Ana, California, and elsewhere in the

County of Orange, State of California (“Judgment and Injunction,”

March 21, 1946, pp 2-3).

Marcus’ “Opening Brief,” September 29,

1945. Marcus is poetic

toward the end of his “Opening Brief” when he argues

Of what avail is our theory

of democracy if the principles of equal rights, of equal protection and

equal obligations are not practiced? Of what avail is our good-neighbor

policy if the good neighbor does not permit honest neighborliness? Of

what use are the four freedoms if the freedom is not allowed? Of what

avail are the thousands upon thousands of lives of Mexican-Americans who

sacrificed their all for their country in this great “War of

Freedom” if freedom of education is denied them? Of what avail is our

“education” if the system that propounds it denies the equality of

all?

Finally,

Marcus slams the door on the defendants’ false premises that upheld

their policies of segregation:

The

indelible imprint of mass discrimination of pseudo theories of

intellectual superiority upon the mind and lives of innocent children

decries the principles of democracy, freedom and justice. . . . .Eager

ears North and South of our borders await the result. We cannot fail

them.

Neither

Judge McCormick (1946) nor the enlightened seven Judges of the Ninth

District Court of Appeals in San Francisco (1947) failed the plaintiff

Mexican families in this historic Orange County civil law case.

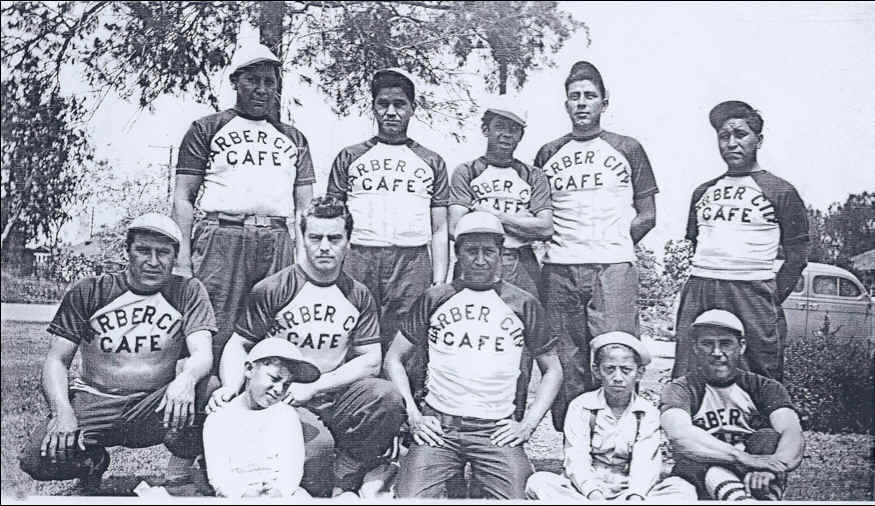

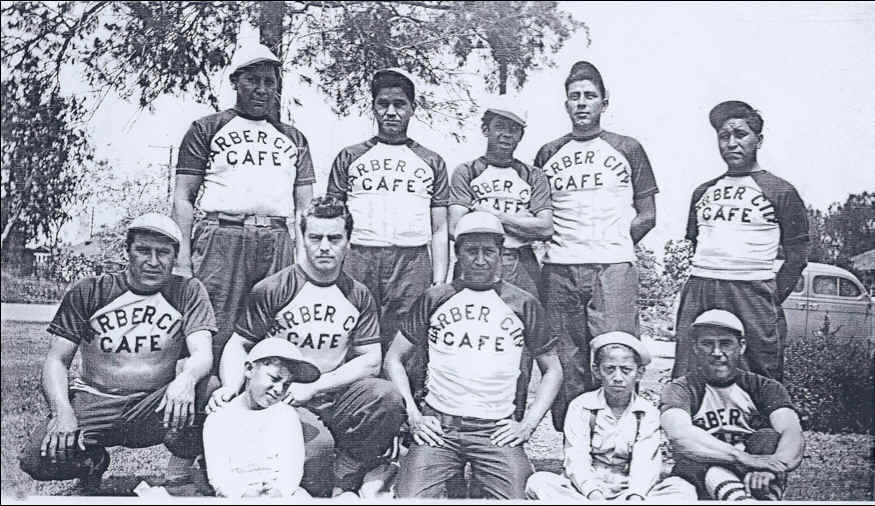

Westminster

Barrio Team WWII Veterans Barber City Community on West Side of Wsmtr

Ca. 1948

TOP

L-R: Joe “Pepe” Rivera; Tony Rivera; Nacho “Glida” Medina; Julio

Méndez; Socorro “Colo” Rivera

BOTTOM:

Jimmy Romero; George Zepeda; Lupe Rivera; Henry “Kiki” Rivera,

Batboy; Rosendo “Chendo/Roy” Vega

FRONT:

George Zepeda Jr(?) Wearing Cap, Batboy

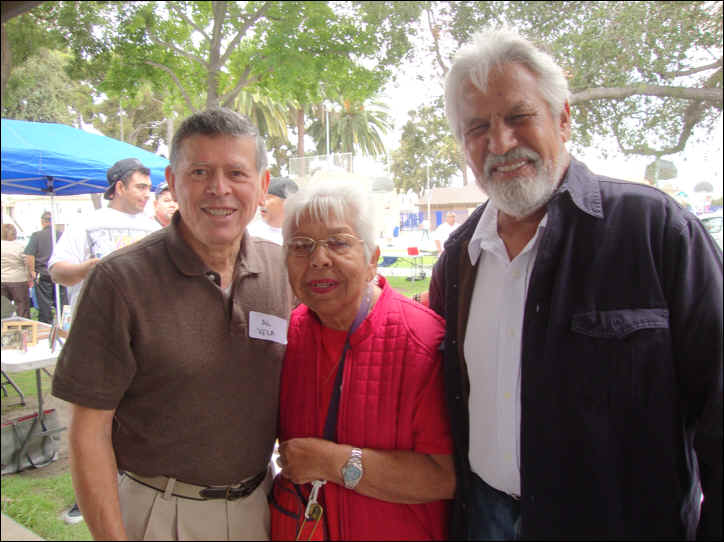

Al

Vela, Pauline Rivera, Gonzalo Méndez Jr Olive Street Reunion Sept 2012

Acknowledgements:

The

author is grateful to his friends and family who contributed to this

story. Among them are my

wife Isabel, Salvador “Chavo” Vela, Julia Vela López, Connie Vela

Goodman, Sal Vela Jr, Frank “Kiko” Mendoza, Angie Hartzler, Tomás

Saenz, Bob Torres, Louie Holguín, Robert Castillo, Socorro “Coco” P

Puebla, Trini Vega, Eddie Espinosa, Stephanie George. . . cristorey@comcast.net

|

“I

cried when they gave it to me, and I told him, [the president] this is

for my mother and father. I never could have imagined as a child

battling segregation that I would end up one day meeting the president

and receiving such a tremendous honor,” stated Mendez.

“I

cried when they gave it to me, and I told him, [the president] this is

for my mother and father. I never could have imagined as a child

battling segregation that I would end up one day meeting the president

and receiving such a tremendous honor,” stated Mendez.

t least 142 U.S. Catholic bishops, representing almost

80% of America’s dioceses, have strongly denounced the religious

persecution expressed in the rules promulgated January 20, 2012 by

Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary of the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human

Services (HSS), in connection with the Patient Protection and

Affordable Care Act, popularly dubbed “Obamacare.” Other major

religious figures like Dr. Albert Mohler quickly followed suit.[1]

t least 142 U.S. Catholic bishops, representing almost

80% of America’s dioceses, have strongly denounced the religious

persecution expressed in the rules promulgated January 20, 2012 by

Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary of the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human

Services (HSS), in connection with the Patient Protection and

Affordable Care Act, popularly dubbed “Obamacare.” Other major

religious figures like Dr. Albert Mohler quickly followed suit.[1]

Dr.

Mohler, an influential leader in the nation’s largest

Protestant denomination and the wider evangelical movement,

sounded off during his

Dr.

Mohler, an influential leader in the nation’s largest

Protestant denomination and the wider evangelical movement,

sounded off during his

The study, ”

The study, ”

From breast cancer to secret Jewish rituals, hidden links signify

unlikely kinships in this meditative exploration of the science of

racial connectedness. Wheelwright, a science journalist, tells the

story of Shonnie Medina, a young Hispano woman in Colorado of mixed

Indian and Spanish ancestry who died of breast cancer in 1999. She

carried a genetic mutation, BRCA1.185delAG, with implications both

scary (a high risk of aggressive breast and ovarian cancer) and

intriguing, because geneticists consider the mutation a reliable

marker of Jewish descent. Wheel-wright maps the mutation’s

itinerary from the Babylonian Captivity in the sixth century B.C.E.,

when geneticists believe it first appeared, through the voyage of

conversos—forced converts to Christianity—from Spain to the New

World, where hints of Jewish practices persist among Hispano

Catholics. But Wheelwright also ties Shonnie’s fate to culture and

temperament: the apocalyptic expectations she drew from her

Jehovah’s Witness faith; her vanity and feistiness, which led her

to reject a mastectomy in favor of “alternative” treatments.

(The author’s quiet indictment of New Age medical quackery is

devastating.) Wheelwright pairs a clear exposition of the

controversial sciences of genetic screening and ethnogeography with

a sensitive account of how a modern identity is woven from ancient

physical and spiritual strands. 10 illus. (Jan.)

From breast cancer to secret Jewish rituals, hidden links signify

unlikely kinships in this meditative exploration of the science of

racial connectedness. Wheelwright, a science journalist, tells the

story of Shonnie Medina, a young Hispano woman in Colorado of mixed

Indian and Spanish ancestry who died of breast cancer in 1999. She

carried a genetic mutation, BRCA1.185delAG, with implications both

scary (a high risk of aggressive breast and ovarian cancer) and

intriguing, because geneticists consider the mutation a reliable

marker of Jewish descent. Wheel-wright maps the mutation’s

itinerary from the Babylonian Captivity in the sixth century B.C.E.,

when geneticists believe it first appeared, through the voyage of

conversos—forced converts to Christianity—from Spain to the New

World, where hints of Jewish practices persist among Hispano

Catholics. But Wheelwright also ties Shonnie’s fate to culture and

temperament: the apocalyptic expectations she drew from her

Jehovah’s Witness faith; her vanity and feistiness, which led her

to reject a mastectomy in favor of “alternative” treatments.

(The author’s quiet indictment of New Age medical quackery is

devastating.) Wheelwright pairs a clear exposition of the

controversial sciences of genetic screening and ethnogeography with

a sensitive account of how a modern identity is woven from ancient

physical and spiritual strands. 10 illus. (Jan.)

From

October 2010 to the end of September 2011, Texas received the smallest

amount of rainfall ever recorded over a 12-month period, according to

the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. One estimate

predicts the drought, which has cost the state’s agriculture industry

more than $5 billion, could last until 2020.

From

October 2010 to the end of September 2011, Texas received the smallest

amount of rainfall ever recorded over a 12-month period, according to

the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. One estimate

predicts the drought, which has cost the state’s agriculture industry

more than $5 billion, could last until 2020.

The

MEXICO Report, a blog dedicated to showcasing positive stories about

Mexico has launched its Real Heroes of Mexico project. The effort will

recognize goodwill efforts taking place in Mexico and those who are

making a difference in their communities. Those nominated for the

awards will be showcased monthly.

The

MEXICO Report, a blog dedicated to showcasing positive stories about

Mexico has launched its Real Heroes of Mexico project. The effort will

recognize goodwill efforts taking place in Mexico and those who are

making a difference in their communities. Those nominated for the

awards will be showcased monthly.