Luis de Carvajal, the younger

(d. December 8, 1596, Mexico City), son of Doña

Francisca Nunez de Carbajal and Don Francisco Rodriguez de Matos,

and a nephew of Don Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva, governor of

Nuevo Leon, New Spain. He was a Spainard by birth, and a

resident of Mexico City. In 1596, he weas condemned to death by

an auto-de-fe. Having been "reconciled" of his

sins, on February 24, 1590, he was sentenced to perpetual

imprisonment in the lunatic hospital of San Hipolito. On

February 9, 1595, he was again arraigned as a "relapso,"

subsequently testifying against his mother and sisters (if the

records are to be believed). On February 25, during one of the

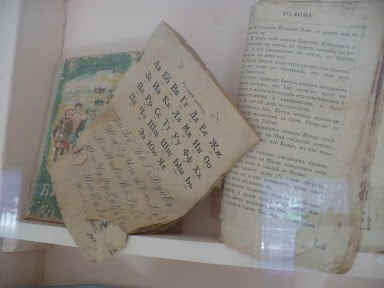

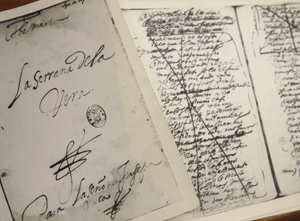

hearings, he was shown a manuscript beginning with the words:

"In the name of the Lord of Hosts" (a translation of

the Hebrew invocation, "be shem Adonay Zebaot"), which

he acknowledged as his own book, and that it contained his

autobiography. On February 8, 1596, he was put on the rack

from 9:30 in the morning until 2 in the afternoon, and during

this torture, he denounced no less than 121 persons, though he

later repudiated his confession.

He and his brother, Baltasar, composed hymns and

dirges for the Jewish fasts: one of them, a kind of "widdui"

(confession of sin) in sonnet form, is given in El Libro Rojo.

The following story is on Don Luis relationship

with Dona Justa Mendez.

----------------

Francisco Mendez married Clara Enriquez ,

(parents of Justa Mendez)

Their known children:

1) Gabriel Mendez-Enriquez

2) Justa Mendez-Enriquez

Justa Mendez met Don Luis Rodriguez de Carvajal,

the younger, (El Mozo). Never married, from this relationship,

he sired a son named Abraham Israel Fernandez de Carvajal (AKA

Antonio Fernandez de Carvajal).

The following is an article written by the Jewish

Historical Society of England.

Don Abraham Israel Fernandez de Carvajal (AKA

Antonio Fernandez de Carvajal) was married to Maria

Rodriguez-Nunez, residents of London, England..

Antonio Fernandez de Carvajal

On the basis, therefore, that the Ferdinand(o)

ancestral line probably passes back through Antonio Fernandez de

Carvajal, I will summarise here the life of this remarkable

individual. Throughout this section I will rely, generally

without further reference, on the secondary sources provided by

numerous publications of the Jewish Historical Society of

England, the wide range of which reflect the importance ascribed

to Carvajal by modern Anglo-Jewish scholars. Primary sources are

generally listed, and often reproduced, within the respective

articles. For convenience I will generally adopt the z

ending of his first surname, though the sources as often use an

s ending.

Early Life

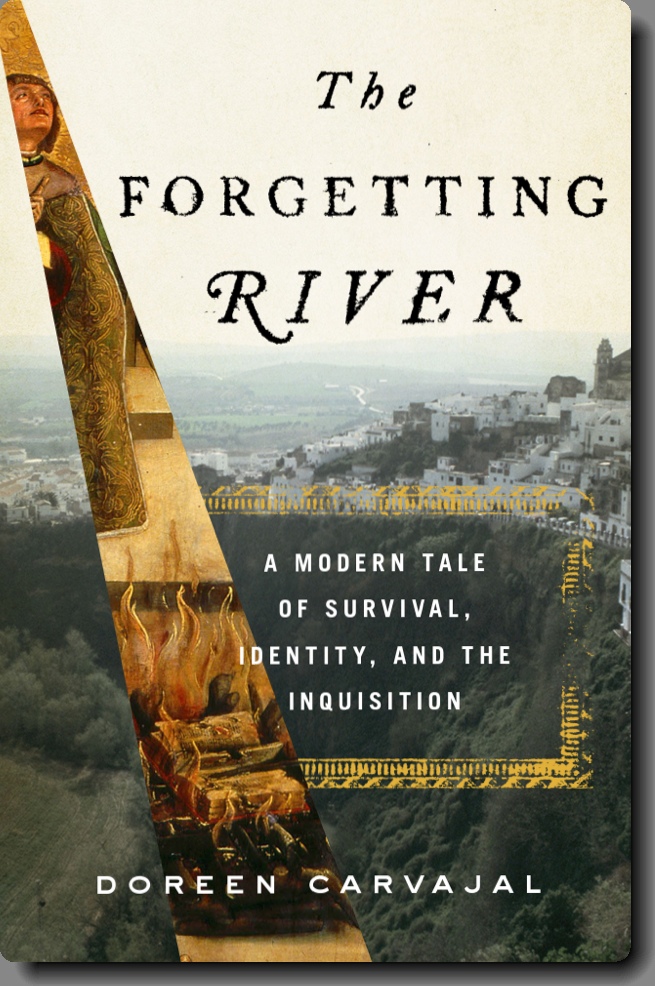

Some periods and aspects of Carvajals life and

character are very well documented, especially those regarding

his trading activities. In other respects, however, he remains a

shadowy and mysterious figure, and this is nowhere better

exemplified than in regard to his birth and early life. By his

own account, giving evidence in a court case in later years,

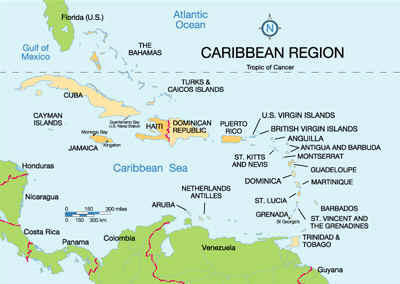

Antonio Fernandez Carvajal spent part of his early life in Fundão,

a small town of Lower Beira in central Portugal below the

northern slope of the Serra da Guardunha, where he was part of

the large and flourishing crypto-Jewish (or marrano)

community who hid their Judaism in order to avoid persecution.

This has sometimes been taken to indicate that he was born

there, as indeed is possible, though it has also been suggested

that he was born in the Canary Islands. It has, however, also

been stated that he spent part of his early life at Santa Cruz

in the Canary Islands, though this is not, of course,

necessarily incompatible with his own account of having spent

time in Fundão. For the time being, at least, his precise place

of birthremains unresolved, though there seems little doubt that

he had early connections both with Fundão and with the Canary

Islands. It has been suggested that he may have been born a

Christian and converted secretly to Judaism, perhaps as a

reaction to the intolerance of the Inquisition, it being stated

in ref.(vi) of footnote 40 that this was true of a large

proportion of the marranos, including those who settled in the

Canary Islands, and in particular including a number of other

Carvajals there.

The writer suggests that the fact that the

discovery in due course that Carvajal had embraced Judaism

caused great surprise also contributes towards the notion that

he was not a Jew by birth. This, therefore, may be perhaps the

likeliest scenario on the evidence, though it remains a

possibility that he was born into a Jewish family which, while

publicly practising Roman Catholicism to evade persecution,

privately adhered to Judaism (ie New Christian, as

distinct from Old Christian borninto the Christian faith).

Whichever of these possibilities represents the truth, these

were dangerous

times for such heresies, and many Jews perished in flames at the

stake during and after this period, both in mainland Spain and

Portugal and in colonies elsewhere, some Carvajals amongst them.

The harshness of the Inquisition regime is illustrated by the

fact that if a victim recanted his or her Judaism at the last

moment and declared themself converted to Christianity, the only

dispensation granted to them was to be garroted at the stake,

thus avoiding the agony of the flames. It has often been stated

that Carvajal was born around 1590, but from his own later

evidence in a court case it appears more

likely that he was born in about 1596-97.

The Inquisition was very active against the Jews

in Portugal during the first quarter of the 17th

century, particularly in Coimbra, a major centre about 50 miles

from Fundão, and this led to a large migration of Jewish

merchants from Portugal to the Canary Islands, where there was

in consequence a revival of marranism. It is likely that

Carvajal was involved in this wave of emigration, whether as a

child or a young adult. He acquired substantial property in the

Canary Islands, and seems to have begun there the process of

establishing himself as a significant merchant. The earliest

reference I have come across which might possibly relate to him

appears in the records of a court case in Amsterdam in 1627, in

which a 35 year old Portuguese in Amsterdam named Antonio

Fernanadesgave a witness statement (see ref.(xviii) in footnote

41). Although the age would not be quite right

and the name is inconclusive, in particular omitting Carvajal,

it would not be inconsistent with what we learn of Carvajal in

later years that he may, perhaps temporarily, have been in

Amsterdam, which at the period contained a significant

population of Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal. This must,

though, remain nothing more than an intriguing possibility.

In 1631 the Inquisition acted in the Canaries

against the influx of immigrants, and investigations revealed a

colony of wealthy Jewish merchants there. It is stated in

ref.(iv) in footnote 41 that a Jorge Fernandez who was included

on a list of people suspected of being hidden Jews was

Antonios brother, though a few years later the same writer

suggests merely that he may have been a close relative of

Antonio (see ref.(vi) of footnote 41). Whatever the truth of

this suggestion, it seems not unlikely that these investigations

and the persecutions they threatened may have persuaded Antonio

to emigrate for a second time to escape the Inquisition. Now in

his thirties, it is likely that he was by this time becoming a merchant of some substance.

Carvajal next made his home and continued his

business activities in Rouen, a city in northern France which

held a small community of Sephardic Jewish merchants with

trading connections in various other European cities. In a

London court case a few years later Carvajal stated that he had

lived in Rouen for 3 years, although it appears likely from the

evidence that the actual length of his stay there may have been

somewhat shorter than this. Like so many other parts of Europe,

Rouen proved not to be immune from the threat of persecution for

the Jews, and as an illustration of what this meant in practice

I will summarise the events that lead to Carvajal moving on yet

again. In 1632 an member of the Rouen marrano community named

Diego Oliveira wished to obtain a grant of naturalisation, and

as part of the process approached a Spanish priest then resident

in Rouen for a certificate of good conduct in relation to

religion. He seems to have chosen badly, since the priest was an

anti-Jewish zealot, and he denounced Oliveira to the

ecclesiastic court as a Judaiser. Oliveira in turn accused the

priest of espionage for Spain in collaboration with a

representative of the Inquisition who had recently come to

France. The court reacted by imprisoning all three and referring

the case to the Parliament of

Rouen, which body was opposed to the grant of

naturalisation to the Portuguese immigrants and, in turn,

referred the matter on to the Royal Court. The priest was

released and ordered to provide evidence for his accusations,

and several members of the Spanish and Portuguese community came

to his support. At least one of these was a former Jew who was

now fully committed to Catholicism and welcomed an opportunity

to denounce his former compatriots as Judaisers. Early in 1633 a

list of 36

alleged Judaisers, including Antonio Fernandes

de Carvajal, was produced, and this inevitably caused

consternation within the marrano community. While most of those

denounced remained in the city others, including Carvajal,

decided that discretion was the better part of valour and fled.

So for the third time in his life Carvajal emigrated to avoid

the threat of persecution, this time to London. Following the

dismissal by the Paris Court of the apostacy charges against

Oliveira, most of those who had fled returned to Rouen, where

the marrano community continued largely unscathed. However, for

whatever reason, Carvajal decided not to return, though he

retained trading links with the city.

So, still in his thirties, and already

established as a substantial merchant, Carvajal began his new

life in London. The Civil War was a few years ahead and Charles

I was still firmly on the throne, though most of the factors

which would bring the country into bloody turmoil were already

in place. For the merchant community, including Carvajal and his

Sephardic compatriots, times were very favourable, not least

because trade beween England and Spain was booming and economic

conditions in Spain

made this business especially profitable for

those based in England. Carvajal and his fellow Jews became an

increasingly prosperous group. I have already indicated that the

dates of Antonio Fernandez Carvajals marriage to Maria

Rodriguez Nuñez and of the births of his two sons are not known

with any precision, but it seems clear from the

facts given earlier that all these events occurred after his

arrival in London. It is unlikely that his wife was born before

about 1620, so she would still have been in her very early teens

when he first came to England. It is, however, interesting to

note that Marias brother Manuel Rodriguez Nuñez, himself a

merchant of substance, had, like Carvajal, lived in Rouen and

was included in the list of 36 alleged Judaisers during the

Oliveira affair (see ref.(xv) in footnote 41). He also moved to

London, either at the same time as Carvajal or subsequently, and

one could speculate whether his younger sister was

with him during this time, and when and where she

and Carvajal first met. It seems likely that they married in

London during the late 1630s, when she was still young, and this

merging of two of the significant merchant families within

Londons crypto-Jewish community would no doubt have been

viewed as a propitious event. Their two sons were probably born

during the early 1640s. It appears that Carvajal may have moved

to the house in Leadenhall Street in which he spent the last

decades of his life in about 1639. This emerges from the

evidence of, rather unexpectedly, Carvajals barber who, on

being called upon by Carvajal in 1656 to testify on his behalf

in a dispute, stated that he had known Carvajal for 18 years

during which time the latter had kept house first in Creechurch

Lane and then in Leadenhall Street, where he had been for 17

years.

It is tempting to speculate that Carvajals

move into the Leadenhall Street house may have coincided with

his marriage, but there is no specific evidence to support this.

An engraving purporting to be of Carvajals house in

Leadenhall Street appeared in the 18 August 1983 issue of the

London cabbies magazine Taxi. A clearer copy of the

same engraving, though described merely as an old house

formerly in Leadenhall Street, appeared on p.186 of vol.2 of

Old & New London by Walter Thornbury (Cassell, prob.

1880-90s), of which I have a copy, where a date of 1672 can

be seen on what appears to be a shop or inn front with the name

L.Litchfield and a cockerel over the door.

Alongside the main door is a scallop-shaped porch

over a decorated doorway which both publications identify as a

synagogue entrance, the Taxi article suggesting that this

is in fact the first Sephardic synagogue in Creechurch Lane. Any

identification of this building as the Carvajal house must

unfortunately be at best speculative, especially since

Carvajals house has been described as being located almost

facing the top of Creechurch Lane, in which case the Creechurch

Lane synagogue would not have been immediately alongside the

house. It is, though, possible that the Creechurch Lane

synagogue, just off Leadenhall Street, may have been correctly

identified in the engraving. The small area of the City close to

Leadenhall Street and Aldgate and contained within the parishes

of St. Katherine Cree and St. James, Dukes Place was where

the early Jewish population of London was concentrated.

Despite the fact that the Inquisition held no

power in England the pre-Civil War years were still potentially

dangerous ones for Jews in London. Although there is evidence

that limited numbers of Jews had lived in England over a long

period of time, achieving in some cases important status in

society, they were as a group still subject to the exclusion

which had begun in 1290 when Edward I expelled all Jews from the

kingdom. Consequently the small but growing number of Sephardic

merchants which emerged in London during the first half of the

17th century, whose foreignness in appearance and speech could

no doubt not be disguised, found it safer to present a public

image of

themselves as Spanish Catholics, notwithstanding

the at-times difficult relations that existed between England

and Spain. They even attended Mass at the home of the Spanish

Ambassador, whilst observing their Jewish faith within the

privacy of their own homes. That this did not entirely protect

them from a degree of persecution is borne out by the fact that

in 1640 Carvajal was successfully prosecuted for recusancy (see

ref.(x) in footnote 41). The habits of secrecy and deception

that this lifestyle demanded must by this time have been second

nature to Carvajal and his fellow Jews, conditioned as he and

they were by their earlier experiences in Portugal, the Canary

Islands and worship began to be held regularly in London, since

the first rabbi of the secret synagogue established

in Creechurch Lane was Moses Israel Athias, a

cousin of Carvajal, whom he had brought over from Hamburg.

Numerous snapshots exist of Carvajals wide-ranging trading

activities over the 2½ decades or so of his life in London,

largely as a result of his and others preparedness to resort

to legal processes in defence of their interests, with cases

arising at regular intervals between 1637 and 1658. Among the

countless products involved in Carvajals dealings were

brushes, buckram, calico, Canary wine,

canvas, cloth, cochineal, coney hats, corn,

drugs, ginger, gum arabic, gunpowder, hose, linen,

looking-glasses, Newfoundland fish, ointment, pewter, Sheffield

knives, sugar, sumach, taffeta, tobacco, whetstones, woollens,

works of art and, significantly, gold and silver bullion.

Seemingly anything which promised a profit came within his

scope. At one stage it was estimated that he was importing

bullion to a value of £100,000 per year, an almost unimaginable

sum in modern terms, especially in view of the risks which

piracy, international politics and even war posed for those

involved in the shipping of goods of such value. Carvajals

trading tentacles reached places as diverse as Bilbao, Cadiz,

Corunna, Malaga and Sanlucar in Spain, Oporto in Portugal,

Venice in Italy,

Dunkirk, Le Havre and Rouen in France, Antwerp

and Ostend in Belgium, Amsterdam in the Netherlands, Terceira in

the Azores, the Canary Islands, Madeira and as far afield as the

East and West Indies, Brazil and Syria, as well as several

British ports in addition to London. Both of these lists emerge

from Carvajals various legal disputes, and there is little

doubt that comprehensive lists would be even longer. It appears

that a typical venture might involve hiring a ship to take goods

from one foreign port to another one where they were sold and

the proceeds used to buy further goods which were in turn

shipped into London. Profit would generally be taken at each

stage though, as the

examples given below indicate, there was always

the risk of loss. Towards the end of his life he was even

purchasing his own ships, presumably in order to cut out the

middle man and maximise his gains. It is of interest to

summarise a few examples of his many dealings. In 1637 one of

his cargoes was turned away from a port in the Azores for fear

of the sickness in London, and during the voyage back home

the ship was boarded by pirates off the Lizard peninsula and

Carvajals goods were plundered. On another occasion, in 1639,

Carvajal had to insist before the High Court of the Admiralty

that goods seized by the port authorities in Plymouth from a

Scottish vessel were in fact

his, and not Scottish-owned. In 1641 he gave

evidence to the same court regarding the alleged purloining of

bullion by the master of a ship sailing from Cadiz to England,

and in a similar case in 1650 the captain of a ship sailing to

London was alleged to have embezzled wine and sugar from one of

his shipments.

In 1653, in testifying in a case concerning

shipments of silver from Cadiz which

had been seized in Ostend, he stated that he had

lived in Spain, and although there does not appear to be modern

evidence to support such a claim, it is not surprising that he

made it, bearing in mind that he and his fellow Portuguese Jews

were at the time posing as Spanish Catholics. In 1656 a ship

named The Peace was seized by Commonwealth forces who

suspected that it was foreign owned, but a witness attested to

the Admiralty Court that he had in fact bought the ship in

Holland on Carvajals behalf for 3,500 Dutch guilders. Seizure

of a cargo by the Inquisition authorities in Oporto in

reparation for a crime allegedly committed by Carvajals agent

was the subject of a dispute in 1657,

and in this case Carvajal had to pay a £200

penalty.

In 1658, not long before he died, in an incident

similar to the affair of The Peace, Carvajal claimed

ownership of a small vessel of 60 tons named The George and

Angel which he had bought 6 years earlier from the

Commissioner of Prize Goods

and which had been seized by Commonwealth forces.

A theme which seems to emerge from a number of these proceedings

is a willingness to be less than entirely straightforward in

relation to certain cargoes, and there are references to

colourable bills of lading in some disputes. It seems to

emerge that Carvajal was himself as open to such dubious

practices as those with whom he found himself in dispute, though

in mitigation it might perhaps be argued that the uncertain

times in which he lived required a certain flexibility. It

was not uncommon for Carvajal to petition the House of Lords or,

in due course, the Lord Protector, for protection or relief in

various matters. One such petition in 1643 concerned a

consignment of gunpowder from Amsterdam seized by the Earl of

Warwick for Parliamentary service, and the following year

he sought restoration to himself of a picture of St Ursula

and the Eleven Thousand Virgins which had been on a ship

bound from Dunkirk to Spain and had been saved when the

ship

was driven close to Arundel Castle. 1643 also saw

him petitioning the House of Lords against an assessment of tax,

and listing payments of nearly £350 he had made, including £100

to each of the service of Ireland and Parliament upon

the Public Faith, £85 paid in Subsidies and £40

paid in Weekly Assessments. In 1646 Parliament had seized

a large cargo of cochineal and bullion for an infraction of

navigation laws, and Carvajal made an advance of money to

Government on the cochineal. When war broke out with Portugal in

1650 his goods and ships were specially exempted from seizure by

a warrant of the Council of State. On more than one occasion,

for example in 1655,

he petitioned Cromwell for protection of ships

carrying his goods from the Canary Islands.

An intriguing entry appears in Spanish archives referring to a

mulatto slave of one Duarte Enríquez who reportedly, when his

master tried to persuade him to be circumcised, refused and

fled, and was subsequently arrested and held in Carvajals

house before being sent to Barbados. On the subject of slavery

it is perhaps with a sense of relief that one notes that there

is no mention of slaves in the list of Carvajals traded

commodities, though one cannot help wondering whether this was

for reasons of conscience or merely for lack of opportunity.

Perhaps it is simply that the British involvement in the

shipping of slaves had not developed suffiently by Carvajals

day.

The English Civil War and the subsequent

Commonwealth regime inevitably impinged significantly on

Carvajals trading activities, and although it appears that

Carvajals sympathies were with the Parliamentary side, this

may have been no more than a pragmatic merchants desire to

align with the winning side. It would perhaps be more generous

to conclude that this was in reality more than mere opportunism,

since the puritan philosophy tended to take a favourable view of

what it saw as the people of the Old Testament, and it would

have been natural for this sympathy to have been

reciprocated to a degree. In 1649 Carvajal was

one of five merchants in the City of London to whom the Council

of State gave the army contract for corn. In common with his

fellow Jewish merchants in London, Carvajal had many contacts

abroad which also made him a valuable source of intelligence for

the Parliamentary side in London. In this he had dealings with

JohnThurloe, Cromwells Secretary of State, who also headed

the Governments Intelligence Service, and it has been

suggested that Carvajal was one of the chief sources of crucial

intelligence to the Commonwealth regime during wars with

Holland, Portugal and Spain. He produced plans for the

revictualling and fortification of

Jamaica, a matter which was of concern to

Cromwell. Carvajal had, therefore, by his latter years,

established himself in a position of some influence not only

within his own relatively small community of crypto-Jews, but

also more widely within powerful circles. He has been described

asamong the most important men in the City and

virtually the treasurer of the Kingdom (see ref.(xvi) in

footnote 41).

While it is frustrating that a man of such

prominence and wealth does not appear to have been represented

in a portrait, it is nevertheless possible to form some

impression of his personality from the many available records.

He emerges as a strong and colourful character who rode horses

and carried side arms, and his resilience and determination are

plain from the account I have given of his facility for

prospering through difficult times. While he was clearly not

reluctant to challenge those who threatened his interests, it

appears that he must also have commanded the respect of those

with whom he came into contact. This may be deduced from an

event which took place in 1645, when for

the second time he and his household were

denounced by an informer for recusancy, in particular for not

attending church under an old Elizabethan Act. His competitors

in trade and many of the leading merchants in the City

petitioned Parliament on his behalf, and as a result the House

of Lords summoned his accuser and quashed the proceedings.

However, he clearly had an abrasive side to his

character, even in old age. In 1658, when he was in his early

60s, he had a dispute with the Commissioners of Customs, whose

officials had seized a cargo of 100 tons of logwood (the

heartwood of a tree used for dyeing) valued at £15,000 which

Carvajal had imported from the Canary Islands, allegedly

illegally. Carvajal collected a group of friends, not all

Jewish, as well as a smith armed with a sledgehammer,

riotously and violently broke into the warehouses where

the goods were impounded, and carried them off, having first

imprisoned the Customs official in charge aboard a ship. The

ensuing legal proceedings were only interrupted by

Carvajals death the following year.

The endenization which Carvajal and his two

teenaged sons were granted in 1655 formally recognised the

priviledged and respected status within England which he had

achieved by this time. They were the first members of the still

small London Sephardic community to be honoured in this way, and

it this fact that prompted Lucien Wolf to describe Carvajal as

the First English Jew18. However, the consequences for

Carvajal were nearly ruinous. At this time he had extensive

property in the Canary Islands, and when war broke out with

Spain these goods were liable to seizure by the Spanish

authorities since Carvajal had just become a British subject. He

sought Cromwells

assistance and a plan was devised which involved

chartering and renaming a vessel, manning it with a Dutch crew

and sailing it to the Canaries. Carvajals agent there, under

instructions from London, loaded all Carvajals goods on board

and provided bills of lading addressed to merchants in

Amsterdam. Finally British men-of-war were instructed to provide

assistance to the ship on its voyage to London. The ruse appears

to have succeeded, and the willingness of the highest

authorities in England to collaborate in such a scheme confirms

Carvajals own high status. After his death Maria Carvajal was

described as widow of a man well known to have been a close

associate of the

Usurper (viz Cromwell) (see ref.(xi) in

footnote 41).

The Re-settlement

By the mid-1650s the Sephardic Jewish community

in London has been estimated to have been about 160 men, women

and children in all. Their usefulness to the Parliamentary cause

had no doubt contributed to their ability to maintain the

pretence that they were Spanish Catholics, but it is difficult

to believe that those who were in close contact with them,

including some of the authorities, were not aware, or at least

suspicious, of their true identity. Among the Puritan faction

which had dominated English politics for over a decade there was

a sense that the Jews should be re-admitted to the nation,

albeit perhaps with a view to their ultimate conversion to

Christianity, and this appears to have been

Cromwells position by the time he accepted the

title of Lord Protector in 1653. There was, however, still anti-semitism

in London, and opposition from many, including some London

merchants, so it was recognised that a formal re-admission would

be bound to provoke discontent. Menasseh ben Israel, a prominent

rabbi based in Amsterdam, came to London in 1655 and petitioned

Cromwell to accept the Jews as citizens of the Protectorate and

to allow them to worship and bury their dead openly. The

matter was discussed in the Council of State and

in a special conference convened in Whitehall, where the main

arguments concerned economics rather than matters of principle,

but no significant conclusion was reached. Meanwhile Londons

marrano community, whilst maintaining their public image as

Catholic Spanish merchants, continued to worship privately as

Jews in their own homes, though seemingly now with the specific

verbal consent of the Lord Protector.Matters came to a head the

following year. The war with Spain which had given rise to

Carvajals difficulty following his endenization also led to

another member of the London Sephardic community,

Antonio Rodrigues Robles, being denounced as a

Spaniard, and as such confronted with a warrant in March 1655/56

for the seizure of his very considerable property. Robles

reaction was uncharacteristically direct for the secretive group

of which he was a part. Encouraged no doubt by the knowledge

that Cromwell was personally sympathetic to the Jewish people,

he petitioned the Lord Protector, declaring himself to be a

Portuguese born and of the Hebrew nation. Robles sought the

support of his fellow Sephardic merchants, and several of them,

including Carvajal, testified that he was indeed what he now

claimed to be. During the subsequent enquiry numerous witnesses

were

called, including ten members of the marrano

community, Carvajal amongst them, and the true Jewish nature of

the community emerged. Carvajal was one of those who declared

that Robles was born in Fundão in Portugal and that they had

known his parents, and it is this testimony which has led to

theview that Carvajal was probably himself born in Fundão.

Despite an attempt by the original informant to bribe a key

witness the case against Robles was eventually dismissed, and

his property was restored to him. It is worth noting in this

matter that, by virtue of the endenization he had been granted

only a few months earlier, Carvajal had less cause than his

fellow merchants to throw his

support behind Robles, since he now already

enjoyed the sort of protection they all desired. It speaks

therefore of his loyalty to his fellow-Jews that he was prepared

to join himself to their cause in such a public way. The Robles

affair must have caused anxiety amongst the small London Jewish

community, and a few days after the case opened Carvajal was

amongst six of their leaders who, together with Menasseh ben

Israel, presented a petition to Cromwell entitled The Humble

Petition of The Hebrews at Present Residing in this City of

London. Thus, for the first time, Carvajal openly admitted

his Judaism, and in fact this document appears to be the first

one in which he used the name Abraham Israel Carvajal. The

petition acknowledged the favours and protection already granted

to the London Jews to carry out their devotions in their own

homes, but sought now written.

Justa, single, married in Mexico City, Francisco

Nunez aka Francisco Rodriguez, a wealthy merchant.

The following is from the Archives of Seville,

Título de la unidad: "Inventario y cuentas

de secuestros y confiscaciones del Tribunal de la Inquisición

de México"

Archivo: Archivo Histórico Nacional

Signatura: INQUISICIÓN,4812,EXP.2

Year: 1642 / 1657

Inventario y cuentas tomadas por el contador de

la visita general de México, Diego Martínez Hidalgo, en 1655 y

1657, a Diego de Cisneros, cerero, Esteban Camorlingo, tundidor,

Juan de Mendoza, ropero, Pedro de Mesa, sombrerero, y Luis de

Medina, dueño de recua, como fiadores de Duarte de León

Jaramillo, depositario secuestrador de los bienes de Isabel Núñez,

reconciliada; y resultas que de dichas cuentas se sacan contra

el contador y receptor, Bartolomé Rey y Alarcón. El inventario

fue realizado en 1642 por el notario de secuestros, Miguel de

Almonacid. También se hallan las cuentas tomadas, por el citado

contador de la visita general de México sobre los bienes de

Luis Pérez Roldán, reconciliado, y Francisca Núñez, relajada,

hijos de Francisco Núñez, alias, Francisco Rodríguez,

abjurado de vehementi, y de Justa Méndez, relajada, y resultas

que de dichas cuentas se sacan contra el contador y receptor,

Bartolomé Rey y Alarcón

Francisco and Justa had the following known

children,

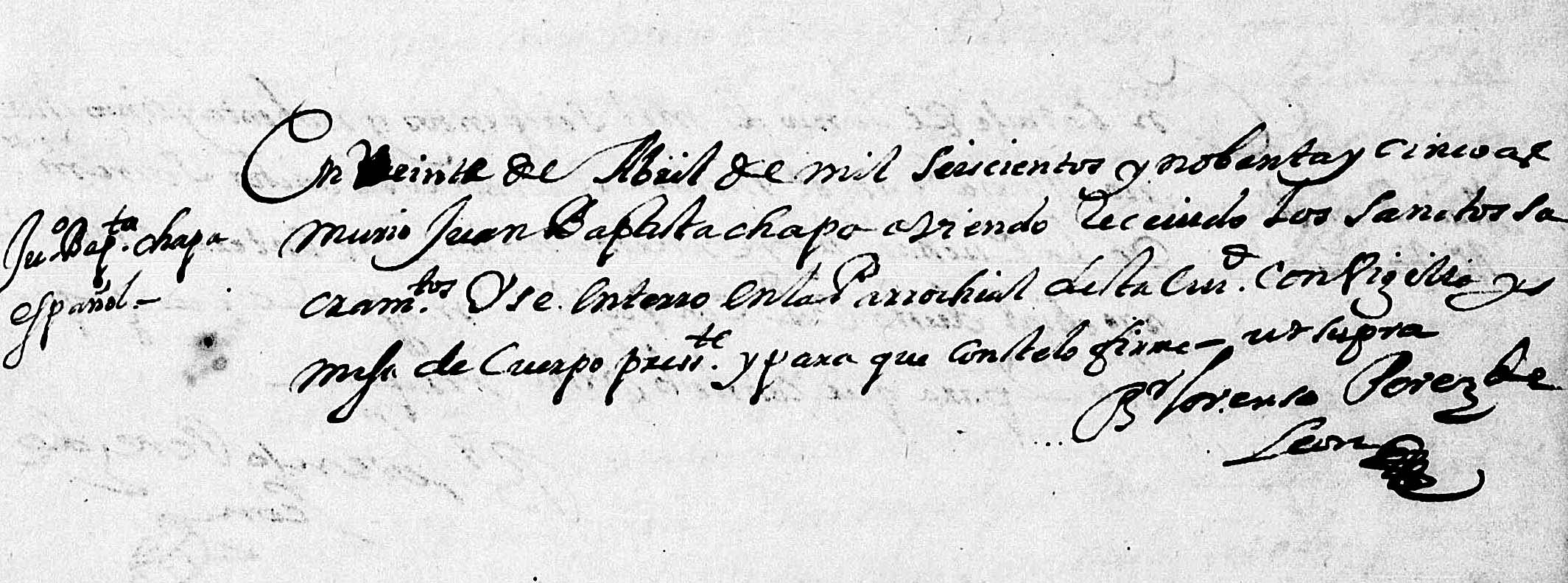

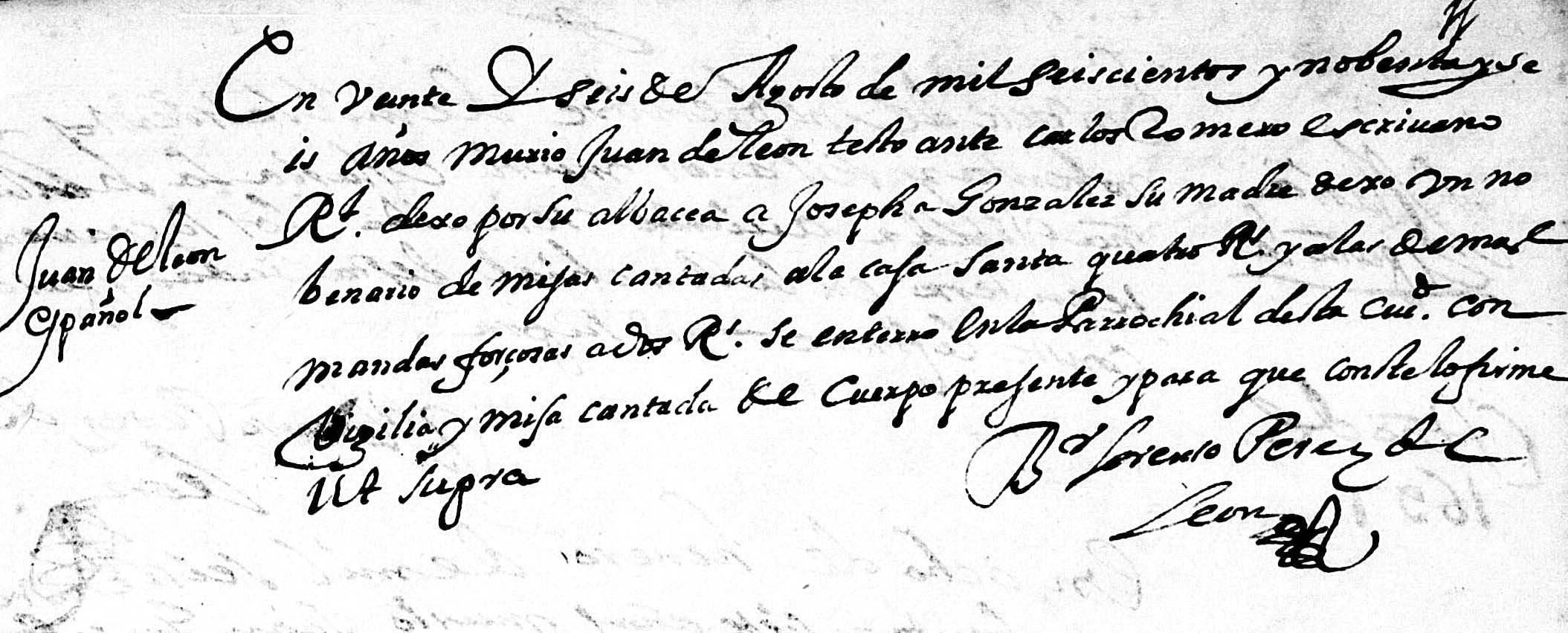

1) Luis Perez-Roldan married on December 13,

1627, Santa Catarina Martir Catholic Church, Santa Catarina,

Mexico City, F.D., New Spain (Mexico) to Isabel Nunez, the

daughter of Diego Hernandez and Leonor Nunez.

2) Isabel Nunez-Mendez, baptized on October, 22,

1603, Asuncion, Mexico City.

3) Francisca Nunez-Mendez, baptized October, 14,

1605, Asuncion, Mexico City.

An auto-da-fé (also auto da fé

and auto de fe) was the ritual of public penance of

condemned heretics that took place when the Spanish and

Portuguese Inquisition had decided their punishment, followed by

the execution by the civil authorities of the sentences imposed.

Both auto de fe in medieval Spanish and auto da fé

in Portuguese mean "act of faith".

Of note: From 1553 to 15583, during the reign of

Cathoic Queen Mary I of England and from 1588 to 1598, reign of

King Albert, the Inquisition was used in England to root out

heresy.

Source; The Martyr Luis de Carvajal, a secret Jew

in Sixteenth Century Mexico, by Martin A. Cohen

Luis de Carvajal The Origins of Nuevo Reino de

Leon, by Samuel Temkin.

Microfilm collection of the Church of Jesus

Christ of Latter Day Saints.

For more Carvajal family research by John Inclan,

click.

ulio Gonzalez Estrada, recognized around the world by the name that graces his most famous tequila, Don Julio, passed away last week at the age of 87. Gonzalez was the real deal, growing up working the fields with his family and starting his own distillery, Tres Magueyes, in 1942 at the age of 17. Not given to drinking tequila himself so much as tasting it, Gonzalez launched what is considered the first luxury tequila, Don Julio, in 1987. He partnered with the Seagram Company Ltd. in 1999 and later sold all of his shares to Londons Diageo PLC in 2005. Gonzalez leaves behind nine children, 25 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

ulio Gonzalez Estrada, recognized around the world by the name that graces his most famous tequila, Don Julio, passed away last week at the age of 87. Gonzalez was the real deal, growing up working the fields with his family and starting his own distillery, Tres Magueyes, in 1942 at the age of 17. Not given to drinking tequila himself so much as tasting it, Gonzalez launched what is considered the first luxury tequila, Don Julio, in 1987. He partnered with the Seagram Company Ltd. in 1999 and later sold all of his shares to Londons Diageo PLC in 2005. Gonzalez leaves behind nine children, 25 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

A former Navy chaplain who fights to defend religious freedom says it's an outrage that Air Force officials appear ready to remove a requirement for Bibles to be placed in on-base lodging rooms.

A former Navy chaplain who fights to defend religious freedom says it's an outrage that Air Force officials appear ready to remove a requirement for Bibles to be placed in on-base lodging rooms.

Executives

of one of the largest public television documentary series on

Latinos to come around in decades say they cant find a qualified

Latino director for their recreations and are instead bringing a

former Director for the BBC, David Belton, for the position.

"Latino Americans," a series which aims to chronicle

the experience, influence and impact of Latinos, is a

production of WETA. Interim Executive Director Beni Matías of NALIP

expressed our concern over this decision, and we include here a

letter from the series executives, and our Board's response. We ask

you to join in the dialogue by writing to us at

Executives

of one of the largest public television documentary series on

Latinos to come around in decades say they cant find a qualified

Latino director for their recreations and are instead bringing a

former Director for the BBC, David Belton, for the position.

"Latino Americans," a series which aims to chronicle

the experience, influence and impact of Latinos, is a

production of WETA. Interim Executive Director Beni Matías of NALIP

expressed our concern over this decision, and we include here a

letter from the series executives, and our Board's response. We ask

you to join in the dialogue by writing to us at

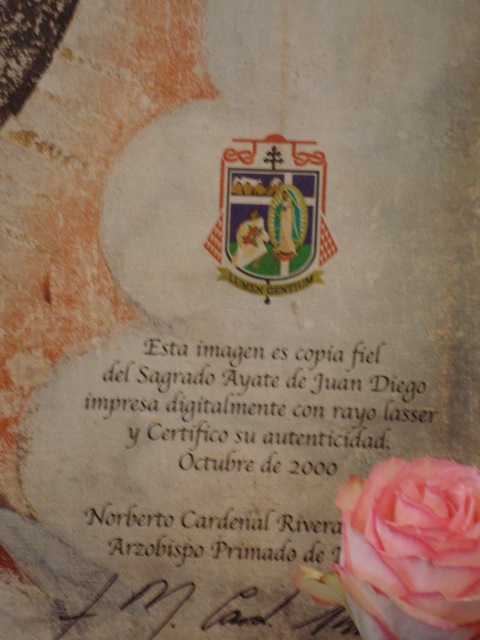

Dan Lynch said this image of

Our Lady of Guadalupe is one of 100 authorized/digitalized images of our Lady based on the original one in Mexico City. You'll notice the cross above her fingers. Dan brought that to our attention. The various other symbols represented in this miraculous image including her blocking out the sun, her power over the moon at her fee, the constellation on her beautiful tilma (unknown color of the time), her mestiza

(morena/brown) skin color, etc. impressed the Aztecs (and other tribes) to the point 10,000,000 converted to the Catholic faith. Take a minute to look at our Lady's face that seems to be alive. . .

Dan Lynch said this image of

Our Lady of Guadalupe is one of 100 authorized/digitalized images of our Lady based on the original one in Mexico City. You'll notice the cross above her fingers. Dan brought that to our attention. The various other symbols represented in this miraculous image including her blocking out the sun, her power over the moon at her fee, the constellation on her beautiful tilma (unknown color of the time), her mestiza

(morena/brown) skin color, etc. impressed the Aztecs (and other tribes) to the point 10,000,000 converted to the Catholic faith. Take a minute to look at our Lady's face that seems to be alive. . .

More

than three decades ago, when Peale was an assistant professor at the

University of Kansas, he was invited to research the Spanish

playwright by the late scholar William R. Manson, an assistant

professor of Spanish at the University of Arizona who had been

researching Vélez de Guevara for years. Together, they pored over

scores of photocopies of Vélez de Guevara's plays, most of them

unpublished.

More

than three decades ago, when Peale was an assistant professor at the

University of Kansas, he was invited to research the Spanish

playwright by the late scholar William R. Manson, an assistant

professor of Spanish at the University of Arizona who had been

researching Vélez de Guevara for years. Together, they pored over

scores of photocopies of Vélez de Guevara's plays, most of them

unpublished.

Kelly

Shackelford, president of Liberty Institute. "We've got

now a step closer to I think what will be a great victory for

our veterans," he tells Associated Press. "We now

have a final order from the court, and it's just a matter now

of getting the land transferred -- and as soon as that

happens, the veterans are going to put that memorial back up

as it has been since 1934."

Kelly

Shackelford, president of Liberty Institute. "We've got

now a step closer to I think what will be a great victory for

our veterans," he tells Associated Press. "We now

have a final order from the court, and it's just a matter now

of getting the land transferred -- and as soon as that

happens, the veterans are going to put that memorial back up

as it has been since 1934."

General

Santa Anna sent General Jose Urrea marching into Texas from

Matamoros, to make his way north along the coast of Texas. On March

19, General Urrea had quickly advanced and surrounded 300 men in the

Texian Army on the open prairie, near La Bahia (Goliad). A two day

battle of Coleto ensued with the Texians holding their own on the

first day. However, the Mexicans would receive overwhelming

reinforcements and heavy artillery. Due to their critical

predicament, Colonel James Fannin and his staff had voted to

surrender the Texian forces on the 20th. Led to believe that they

would be released into the United States, they returned to their

former fort in Goliad, now being their prison.

General

Santa Anna sent General Jose Urrea marching into Texas from

Matamoros, to make his way north along the coast of Texas. On March

19, General Urrea had quickly advanced and surrounded 300 men in the

Texian Army on the open prairie, near La Bahia (Goliad). A two day

battle of Coleto ensued with the Texians holding their own on the

first day. However, the Mexicans would receive overwhelming

reinforcements and heavy artillery. Due to their critical

predicament, Colonel James Fannin and his staff had voted to

surrender the Texian forces on the 20th. Led to believe that they

would be released into the United States, they returned to their

former fort in Goliad, now being their prison.