It cost the U.S. $375 million, thousands of lives, a movement for

national independence — and a Nicaraguan postage stamp — to take

over and finish construction of the Panama Canal, rightly chosen in

1996 by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) as one of the

engineering wonders of the world.

And now, Panama is gearing up for the largest modernization plan in

its 92-year history. Voters in October approved a $5.25 billion

expansion of the canal that will include a third set of locks on the

Atlantic and Pacific sides to handle the world’s largest ships.

Construction will begin in 2007 and is expected to last eight

years.

A canal was first conceived in the early 16th century by King

Charles V of Spain, who ordered the governor of the region of Panama

to survey a route following the Chagres River to the Pacific. This was

the first survey for a proposed ship canal through Panama, and more or

less followed the course of the present Panama Canal.

The desire to build such a canal gained additional impetus during

the 1848 Gold Rush, when prospectors could either sail around Cape

Horn, cross the Great Plains, or journey across the isthmus by foot or

canoe and then take ship north from the Pacific coast. The first

interoceanic railroad in the world was constructed on the isthmus in

1855 but the opening of a canal would mean travelers sailing from, as

an example, San Francisco to New York went from a journey of 14,000

mi. (22,500 km) around Cape Horn at the bottom of the continent to one

of a mere 6,000 mi. (9,500 km).

The United States had long been interested in the possibility of

building a canal and in the latter half of the 1890s set up two Canal

Commissions to look into the question of the best route. Both

recommended running the canal through Nicaragua.

The French, however, had already begun the endeavor and were

continuing with the task of constructing a canal located in Panama.

The Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interoceanique had been granted a

concession to do so in 1878 and had been at work on it since 1881.

Headed by Count Ferdinand de Lesseps, world famous for building the

Suez Canal, the company planned a sea-level canal, which it estimated

would take 12 years to build at a cost of approximately $l30 million.

Tens of thousands flocked to invest in the project, but in late

1889 the company was declared bankrupt, defeated by months of tropical

weather whose torrential rain caused constant mud and rock slides,

disease-carrying mosquitoes, deadly snakes, inadequate equipment and

management, and a work site situated in dense jungle spread out over

mountainous terrain.

Undaunted by this spectacular although understandable failure,

another French company — Company Nouvelle du Canal de Panama — was

started up in l894 and took over the job. However, it too was unable

to complete the canal and its assets, rights, and equipment were

therefore offered for sale.

A Volcano Sways Voting

Although both Canal Commissions had recommended Nicaragua as the

best place to build a canal, the engineers consulted were in favor of

Panama, David McCullough wrote in “The Path Between The Seas: The

Creation of the Panama Canal 1870-1914.”

There were a number of reasons to choose Panama. Among them were

the canal would be shorter by more than 100 mi. (161 km), the proposed

Panamanian route already possessed a railroad, and overall running

costs would be lower.

Efforts to convince American legislators that Panama was a better

choice were aided by two investors in the French company, Philippe

Bunau-Varilla and William Cromwell. They mounted an effort to swing

the vote to Panama, which would benefit them and other stockholders if

the bankrupt company in which they held shares was sold to the United

States. To this end they lectured, issued pamphlets, and purchased

numerous advertisements in various publications, all pointing out the

benefits of building the canal in Panama as opposed to Nicaragua —

and in particular stressing the suggested canal site in the latter was

only 20 mi. (32 km) from an active volcano.

The question was debated during the 1902 legislative session. When

the matter came up for voting in the Senate, Bunau-Varilla and

Cromwell carried out a masterly piece of persuasion by sending every

senator a Nicaraguan stamp featuring the volcano in full eruption.

The legislature chose Panama as the site of the proposed canal,

although the vote was very close, and President Theodore Roosevelt

signed the Panama Canal Act into law on June 28, 1902.

The Act authorized Roosevelt to acquire not only all rights and

property of every kind, “real, personal, and mixed,” and all other

assets possessed by the French company, but also the necessary strip

of land from Colombia, there to exercise “the right to use and

dispose of the waters thereon, and to excavate, construct, and to

perpetually maintain, operate, and protect thereon a canal.”

There is no doubt Roosevelt viewed the canal as being of prime

importance, having declared in his December 1901 State of the Union

address that “No single great material work which remains to be

undertaken on this continent is of such consequence to the American

people as the building of a canal across the Isthmus connecting North

and South America.”

It appears his views were heavily influenced by a book written by

Alfred Thayer Mahan, U.S. naval officer and scholar. This book, “The

Influence of Sea Power Upon History,” was published in 1890 and

advanced the theory that national and commercial supremacy were

directly related to control of the sea. This point of view was

important in the drive for construction of the Panama Canal.

Panama Gains Independence

Even so, the project was not set for plain sailing since before

construction could begin, the United States had to negotiate a treaty

with Colombia, which then controlled Panama. Despite a very generous

offer — $l0 million to be paid immediately, followed by $250,000

each year of a century-long lease for 6 mi. (10 km) of land on each

side of the canal — the Colombian government turned it down. It was

a time for bold action.

Panama rose up and demanded its independence. The USS Nashville

arrived with an official mission to protect American citizens,

thwarting any attempt by Colombia to send troops to Panama by sea. The

jungle prevented them from bringing military forces over a land route,

so they were unable to crush the Panamanian movement.

Thus it was the Republic of Panama came into being on Nov. 3, 1903.

The U.S. government obtained a treaty later that year, under which the

United States gained the right to build a canal under essentially the

same terms as had been offered to Colombia.

The United States began to move forward in 1904. As laid down in

the Act, it purchased Compagnie Nouvelle du Canal de Panama’s assets

for $40 million, taking over the project on May 4, 1904. An Isthmian

Canal Commission was set up to govern the Canal Zone, although overall

supervision of construction was in the hands of the U.S. Secretary of

War. Expectations about the canal were plainly stated by Roosevelt:

“What this nation will insist upon is that results be

achieved.”

The man who arrived in June 1904 to take up the post of chief

engineer was a civilian, John Findley Wallace.

A State of Chaos

Wallace discovered the project in a state of chaos. While the

French had constructed housing and other facilities for the benefit of

their workforce, many of these buildings were now inhabitable. Their

huge fleet of abandoned equipment — much of which was in various

stages of decay — had to be examined, repaired or rehabilitated if

possible, and then card-indexed for swift location as needed.

While most of the professional workers were American, laborers were

largely recruited from various Caribbean countries, including

Barbados, Guadeloupe and Martinique. Dozens of nations were

represented by the workforce, and interpreters were in demand. Beyond

skills more directly concerned with construction of the canal, many

other professions were represented, ranging from secretaries,

accountants to shop clerks and pharmacists, doctors and nurses.

William R. Scott spent five months in Panama, three as an employee

of the Isthmian Canal Commission. In l913 he published “The

Americans in Panama,” in which he mentions workers’ wages and

salaries. Hourly remuneration ranged from l0 to 25 cents an hour for

apprentices to 65 cents for bricklayers and up to the same amount for

carpenters, coppermiths, pipefitters and linesmen. Ironworkers and

machinists were paid as much as 70 cents an hour. A steam shovel

operator earned between $2l0 and $240 a month. While these rates

appear small, they were far more than would be paid for comparable

work in the United States, and were in addition to free housing and

medical care at no cost.

Wiping Out Disease

One of the first major jobs the Americans undertook was carrying

out sanitary improvements to deal with the high death toll from

disease, most often malaria and yellow fever. At the time, the

discovery both illnesses were carried by mosquitoes was only beginning

to be accepted. The effort was led by Chief Sanitary Officer William

C. Gorgas of the U.S. Army. Even so, it was an uphill battle which

ultimately involved adding screens to doors and windows, fumigating

dwellings, and laying oil weekly on cesspools and cisterns to kill

insect larvae.

In addition, the United States paved streets and constructed water

and sewage systems for Panama City and Colon. Once this was done, the

hitherto common use of barrels to store water for domestic use was

ended, thus removing thousands of potential mosquito breeding grounds.

Rufus E. Forde contributed recollections of working on the canal to

the Isthmian Historical Society in l963. Forde recalled that from a

gang composed of approximately l25 workers, 40 or so would come down

with malaria before noon. It was a sight so frightening, he said, that

“sometimes you don’t come back after dinner.”

Canal workers were instructed to drink quinine to treat malaria,

but its taste was so vile many claimed they had taken theirs when they

had not in fact done so, he added.

Wallace had not supported Gorgas’ efforts because he did not

believe the diseases were transmitted by mosquito, and while John F.

Stevens, the chief engineer who replaced him, admitted to not being

entirely convinced as to the efficacy of Gorgas’ proposed

eradication program, he nonetheless supported it. Ira E. Bennett’s

“History of the Panama Canal” quoted Stevens’ opinion there were

three diseases on the isthmus:

“Yellow fever, malaria, and cold feet.”

Gorgas’ draconian measures succeeded and it was announced in

December 1905 that yellow fever had finally been eradicated from the

isthmus. However, malaria still caused many deaths among workers

because surviving it did not make the patient immune to further

attacks. Hospital records show that 5,609 people died from disease or

accidents during the American construction era, and 4,500 of them were

black employees.

Once under control, stern measures were taken to keep the isthmus

disease-free. Quarantines were rigidly enforced and inoculations

mandatory. Scott’s book mentions an incident in 1905 when a number

of workers from Martinique initially refused to leave their ship

because they believed vaccination scars were intended to mark them so

they could not go home. He related that they were removed from their

vessel at bayonet point and then inoculated.

Facilities for the Workforce

Chief Engineer Wallace found the going difficult. Despite all

efforts, housing and food for the workers were not of acceptable

quality. He expressed anger about “red tape” constantly

interfering with the running of the project, and also was worried

about his family being stricken with disease, particularly after his

secretary’s wife died of yellow fever. There had been personality

clashes with the chairman of the commission and although the

commission was dissolved and a new one set up, Wallace, who had

received an offer of a better paid job in the United States, resigned

a year after his arrival.

Another civilian, John F. Stevens, took over as chief engineer in

July 1905. He had excellent references, having been in charge of the

construction of the Great Northern Railroad in the Pacific Northwest.

After Stevens’ arrival, the United States used 12,000 of its

workforce to construct buildings as well as carry out excavation work.

Between 1905 and 1907 clinics and hospitals, laundries, libraries,

mess halls, churches, hotels, social and fraternal clubs, and many

other amenities were built. Numerous workers had brought their wives

and families with them, and schools were provided. Fire departments,

courts and post offices came into being and shops sold household

goods, canned items and perishables kept in refrigerated storage.

Saturday night dances were held at hotels and firework displays,

lectures, and other types of entertainment (including a circus on at

least one occasion) also were available to the workforce.

The Panama Record, published weekly, provided news of sporting

events and contests, social gatherings, and notices of various sorts,

as well as committee reports and official announcements.

Recreational facilities eventually included bowling alleys, gyms,

ice cream parlors, billiard rooms, tennis courts and baseball parks.

Contests involving various sports were held, with keen competition

between teams.

The immense logistical problems involved in providing life’s

necessities can be demonstrated by noting meals for the workforce

required the annual baking of more than 60,000 rolls and 6 million

loaves, as well as approximately 110,000 lbs. of cake.

Improving a Vital Rail Link

Another task to be accomplished was improving transportation. The

Panama Railroad ran past the excavations but had descended into a

degraded state. Its efficient operation was vital to the job, since

there were no highways and the railroad had to move everything needed

from construction equipment and building materials to food, medical

supplies, and excavated material, not to mention the workforce itself.

The French company’s holdings included a number of locomotives

and wagons. Most were considered too lightweight for the tasks they

had to accomplish, although some were eventually rehabilitated. The

rail system was overhauled and more robust American rolling stock

suitable for handling the movement of heavy equipment and to haul

excavated material away from the diggings were shipped in. The

workforce included experienced American rail staff whose task was run

the railroad — once it had been built from components shipped to

Panama in a dismantled state.

Make the Dirt Fly

Roosevelt had made it plain workers were expected to “make the

dirt fly,” but construction plans had to be flexible in order to

meet challenges as work continued. For example, the width of the

Culebra Cut was changed from 200 to 300 ft. (61 to 91 m) while after a

request from the U.S. Navy lock chambers were increased to 110 ft. (34

m) wide. This was to ensure the canal would allow passage of vessels,

which at the time were still themselves in the design stages.

Landslides continued to be a continual and often fatal occurrence.

Exacerbated by the tropical rainy season, they also destroyed

equipment and buildings and filled in newly excavated portions of the

canal, which then had to be redug.

Accidents, of course, were unavoidable. A number of people who had

worked on the canal reminisced about that aspect of the job at a

gathering organized by the Isthmian Historical Society in 1958.

Reed E. Hopkins, former railroad conductor, recalled standing

orders that if anyone was hurt, conductors had to take them

immediately to the hospital. It happened daily, since although

dynamite blasts were usually timed for 11:30 a.m. and 5:30 p.m., they

were sometimes set off without warning and flying debris took its

toll.

Gertrude B. Hoffman, a teacher, spoke about a premature blast at

Bas Obispo, where the father of one of her pupils took cover in the

dipper of a steam shovel. The shovel ended up entirely covered with

chunks of rocks.

Charles F. Williams described seeing a train in Colon Station, its

luggage car marked funeral car and behind it a coach for passengers

being taken to hospital. Such cars were, he said, “regular equipment

on the Panama Railroad.”

Third Chief Engineer Arrives

Chief Engineer Stevens was instrumental in persuading President

Roosevelt and Congress that the canal should be built with locks,

rather than the proposed sea level waterway. In strongly-worded

evidence to the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, he

declared the greatest problem in the construction of any canal across

the isthmus was going to be controlling the Chagres River — and

equally emphatic that a system of locks would solve it. In June l906

the final vote was taken, and a lock canal was approved, albeit by a

narrow margin.

However, Stevens resigned in 1907, citing personal reasons. A third

commission was set up to oversee the project. It was composed mainly

of military men and George Washington Goethals, then holding the rank

of major in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, became chief engineer of

the project. Being in an officer in the army, unlike the two previous

chief engineers he could not leave the project until permitted to go

elsewhere.

Goethals was not one to mince words. Bennett’s book relates he

addressed his workforce in the stirring fashion of an army man.

“I am commanding the Army of Panama; the enemy is Culebra Cut and

the locks and the dams.”

Nor did he exaggerate. The Culebra Cut is approximately 9 mi. (14.5

km) long and had to be dug through the Continental Divide. When the

Americans took over, the two French companies had already excavated

more than 78 million cu. yds. (60 million cu m) of which approximately

18,600 cu. yds. (14,220 cu m) of material had been taken from the Cut.

Ralph E. Avery described the French excavators in his 1913 work

“America’s Triumph” in Panama. They were the type fitted with

chains on buckets, which dropped spoil into hoppers which then

transferred it into dump cars. It was to be over a year before steam

shovels completely replaced these excavators.

Dynamite and Steampower

By today’s standards, the construction of the canal was carried

out by primitive methods, since it was largely accomplished by

laborers, dynamite and steam power.

Preparation for rock blasting was carried out by drills run on

compressed air piped from three plants some five miles away from the

work site. Operating in sets of up to a dozen, set between 6 and 16

ft. (2 and 5 m) apart, the drills cut down as deep as 27 ft. (8 m).

Steel hand drills also were used. Bennett related that holes were

originally fired with the use of batteries and later by electrical

current. He mentioned the largest single blast involved setting off a

number of holes which together contained 52,000 lbs. (23,587 kg) of

dynamite.

Goethals described the extensive use of explosives in a talk given

to the National

Geographic Society in 1911. Apart from blasting, dynamite also was

used to break up rocks too large for the steam shovels to handle.

Goethals related that in those cases three or on occasion more sticks

of dynamite were laid on the rock, covered in mud, and set off by use

of a slow match. Most of the dynamite was used at the Culebra Cut.

Disposal of the massive amounts of spoil involved was handled by

trains pulling a score or so of Lidgerwood flat cars, each capable of

hauling approximately l9 cu. yds. (15 cu m) of material. These cars

were one-sided and steel plates joined each car into what amounted to

a continual surface, necessary for the method used to unload them.

This was accomplished by means of attaching a car carrying a plow

and another featuring an unloader at opposite ends of the train.

Unloaders had a steam-driven windlass around which a wrist-thick steel

cable was wound. Thus equipped, the train was driven under a frame to

which the cable was attached and as the train moved on, the cable paid

out until it reached, and could be attached to, the plow. Rewinding

the cable pulled the plow forward, pushing excavated material off the

cars to the waiting spreaders. The plow and unloader were detached and

the empty train returned to the diggings. This work also was handled

with Western dump cars, which ran on compressed air, and some

unloading was done by hand.

As much of this excavated material as possible was recycled for

such purposes as constructing a 3-mi. (5 km) long breakwater

constructed as an anti-silting measure as well as building the Gatun

Dam, which tamed the Chagres River and created Gatun Lake. It also was

used to reclaim 500 acres (202 ha) of the Pacific. In addition,

millions of cubic yards of material was dumped into the jungle.

The disposed material often included a large amount of rock and

earth from landslides. In his lecture to the National Geographic

Society, Goethals stated in fiscal year 1908 alone approximately 6

percent of the material removed was deposited by slides, while two

years later the proportion had risen to 18 percent.

The problem was finally resolved by grading the slopes of the Cut

to a less steep angle than had hitherto been attempted.

Record Amounts of Excavation

Goethals’ arrival heralded the onset of a period of record

accomplishment. Bennett stated that despite the fact it was the rainy

season, in August 1907 a record 1 million cu. yds. (764,555 cu m) was

excavated, a figure doubled and then tripled during the following

months. The workforce kept up the pace and in two years had removed

approximately 73 million cu. yds. (55.8 million cu m).

In 1907 the equipment fleet increased to include 100 steam shovels,

560 drills, more than 50 cranes and 20 dredges. The annual consumption

of fuel was approximately 500,000 barrels of oil and 350,000 tons

(317,515 t) of coal.

Numerous American companies sent their equipment to Panama.

Among them, the Bucyrus Company of South Milwaukee, Wis.,

manufactured the majority of the steam shovels used on the job.

Shovels also were supplied by the Marion Steam Shovel Company of

Marion, Ohio, and the Harry A. Lord Company of Allegheny, Pa.

The largest shovels were 95 ton (86 t) models with 5-cu.-yd. (4 cu

m) dippers, and 45- and 70-ton (41 t and 64 t) shovels also were used.

In May 1912 a Marion model 9l steam shovel set a world record by

moving more than 5,550 cu. yds. (4,243 cu m) of material.

One or two of the steam shovels, which worked on the canal have

been traced. A Marion model 60 present in Panama in l904 was reported

fronting a museum at the University of Costa Rica. Another canal-era

Bucyrus steam shovel was borrowed from a private owner in Montana and

exhibited in “Let The Dirt Fly,” the 1999 Smithsonian Institution

exhibition devoted to the construction of the canal.

Harry A. Franck worked on the project for several months in 1912,

first as a census enumerator and subsequently as a policeman. “Zone

Policeman 88: A Close Range Study of the Panama Canal and its

Workers,” his lively memoir of the time he spent in the Panama Zone,

was one of the best selling books of 1913. He provided a colorful

picture of the work carried out by the steam shovels, describing their

mammoth strength coupled with the ability to work at delicate tasks

such as picking up a single railroad spike.

“They ate away the rocky hills,” he wrote, “and cast them in

great giant handfuls on the train of one-sided flat-cars that moved

forward bit by bit at the flourish of the conductor’s yellow

flag.”

Steam shovel crews consisted of a craneman who perched on its arm

and the engineer who operated the controls, each shovel being

accompanied by a gang of laborers. The latter came from many nations

and sometimes unexpected professions. Franck noted a Spanish laborer

killed at the Culebra Cut by a dynamite explosion was discovered to be

a celebrated lawyer in his home country.

Steam Shovel Work Honored

The sterling work of the steam shovels is recalled in a bronze

plaque commemorating Lieut. Col. David DuBose Gaillard, who oversaw

excavation at the Culebra Cut between the summers of 1908 and 1913,

and after whom the Cut was subsequently renamed. The plaque shows two

laborers digging in the Cut, a pair of steam shovels in the

background. It is now displayed at the bottom of the steps in front of

the Canal Administration building in Balboa, close to the Goethals

Memorial.

In addition, a stamp issued in 1951 depicted laborers from the West

Indies working on the Culebra Cut, with a steam shovel shown on the

far left. Steam shovels and other equipment also can be seen in murals

decorating the rotunda of the Canal Administration’s building, which

record work at the Cut, the Gatun Dam, and the locks.

Steam shovels working on the canal were mounted on cars running on

rail lines, which were relocated as necessary by track shifters

invented by William G. Bierd, who previously held the post of general

manager of the Panama Railroad. With their aid, whole sections of

tracks could be quickly moved between approximately 2.5 and 9 ft. (.7

and 3 m) in one “throw” when the task in hand required it.

Dredges and Hoists

Dredges working on the project included a 20-in. (51 cm) hydraulic

pipe line model, manufactured by the Ellicott Machine Company of

Baltimore, Md. It cost $158,000 and could excavate 750 cu. yds. (573

cu m) of material an hour.

Other dredging equipment was supplied by the Haywood Company and

Froment & Company, both based in New York City, as well as the

Atlantic Gulf & Pacific Company, also of New York.

A. L. Ide & Son, based in Springfield, Ill., supplied dredge

engines, while centrifugal pumps were provided by the Morris Machine

Works of Baldwinsville, N.Y.

The equipment fleet also included four rebuilt iron-hulled ladder

dredges salvaged from the holdings of the French company. The buckets

of these dredges could move 15 cu. ft. (.4 cu m) of material, working

down to a 45 ft. (14 m) depth.

Equipment provided by the Brown Hoisting Machinery Company of

Cleveland, Ohio, handled heavier work, such as unloading coal. Coaling

cranes manufactured by Orton & Steinbrenner of Chicago, Ill., also

worked on the job, and another Cleveland manufacturer with a similar

name, the Browning Engineering Company, provided cranes.

Scott reported the cost of the canal up to July 1912 was $260

million, including the $40 million used to purchase the French

company. By then construction and engineering had cost $152 million

and sanitary improvements $15 million. Bennett set the cost of

excavating the Calubra Cut alone at between $l0 million and $l5

million a mile.

Building the Locks

The construction of the canal’s giant locks provided another

snapshot of just one part of the huge task facing the builders.

Some notion of the vast size of these locks is indicated by the

numbers: the walls bisecting the locks into two chambers are

themselves 60 ft. (18 m) wide. The thickness of side walls ranges

between 45 to 50 ft. (12 and 15 m) on the lock floor, and the

culverts, which carry water to the locks have a diameter of 18 ft.

(5.5 m).

During the construction of the Gatun Locks, concrete was delivered

by a new method involving a circular electric railroad.

Steel cars divided into two compartments (one for premeasured

amounts of sand and stone and the other for cement) were loaded and

sent to eight concrete mixers, each with a 64 cu. ft. (1.8 cu m)

capacity. Once mixed, concrete was loaded into rail cars and rerouted

to 85 ft. (26 m) high Lidgerwood cableways spanning the locks. Full

buckets were caught up and carried across the lock for placement as

necessary, while the empty buckets for which they were exchanged were

already returning to be refilled with material for the concrete mixers

so the cycle could begin again.

At Pedro Miguel and Miraflores on the Pacific end of the canal a

similar system for mixing and placing concrete was operated with the

aid of cranes and steam locomotives Lt. Col. Harry F. Hodges was in

charge of the design and erection of the lock gates. McClintic-Marshall

Construction Company, of Pittsburgh, Pa., was awarded the contract for

this part of the job. Ranging in height from 47 to 82 ft. (14 to 25

m), the gates are 7 ft. (2 m) thick, and comprise two leaves over 60

ft. (18 m) wide, weighing between 390 and 730 tons (354 and 662 t)

apiece.

Franck’s book provides a glimpse of the construction of the Gatun

Locks. Describing its steel gates, which he saw standing ajar, as akin

to “an opening in the Great Wall of China.” He goes on to say,

“On them resounded the roar of the compressed-air riveters and all

the way up the sheer faces, growing smaller and smaller as they neared

the sky, were McClintic-Marshall men driving into place red-hot

rivets,” tossed up to them from workers at the forges, their

trajectory “glaring like comets’ tails against the twilight

void.”

Ships are not permitted to pass through the locks under their own

power. General Electric in Schenectady, N.Y., provided “mules,” as

the electric locomotives, which pull vessels through the locks are

known.

A Greater Work Than They Realized

The importance of the canal was highlighted in November 1906 when

Theodore Roosevelt visited Panama to inspect progress on the job, the

first time a sitting president had left the country.

In a speech to the workforce at Colon, after complimenting the

“steam-shovel man” as “the American who is setting the mark for

the rest of you to live up to.” Roosevelt went on, “This is one of

the great works of the world; it is a greater work than you,

yourselves, at the moment realize.”

In his speech, Roosevelt promised to see if he could arrange for

“some little memorial, some mark, some badge, which will always

distinguish the man who did his work well on the Isthmus,” and

indeed this came to pass. Medals struck from scrap metal taken from

abandoned French equipment were issued to Americans who had worked for

two years on either construction or the railroad. Bars marking each

subsequent two year period of service on the project were issued

thereafter.

The distribution of 50,000 bronze Panama Canal Completion Medals

marked the opening of the s-shaped 51-mi. (82 km) long waterway on

Aug. 15 1914.

When the United States took over building the canal — and for

some time afterwards — naysayers said such a waterway could never be

built. Yet in only 10 years persistence, grit, and technical

knowledge, aided by an army of laborers and heavy equipment, saw the

job through to completion. CEG

Among the members of this family, of some of whom a more detailed

account will be found below, are the following: Aaron de Castro, or

Crasto, parnas, Amsterdam, 1834; Abraham de Castro, who was among

the Jews who returned to Amsterdam from Brazil when that country was

lost to the Hollanders in 1654 ("Publ. Am. Jew. Hist.

Soc." iii. 17); Abraham Nahamias de Castro, London, 1769; Dr.

Baruch de Castro, Amsterdam, 1597-1684; Daniel de Castro, brother of

Baruch; Daniel Gomez de Castro, parnas, Amsterdam, 1772; Dr. Ezekiel

de Castro, Verona, 1639; Imanuel de Imanuel Nahmias de Crasto,

parnas, Amsterdam, 1773; Dr. Isaac de Castro, surgeon, Amsterdam,

1683; Joseph Mendes de Castro, London, 1694; Mordecai de Castro,

Amsterdam, 1650; Moses Gomez de Castro, parnas, ib., 1784;

Nissim de Castro, Constantinople, nineteenth century; Pedro

Fernandes de Castro, alias Julio Fernandez de Castro of Valladolid,

son-in-law of Simon Vaez "Publ. Am. Jew. Hist. Soc." iii.

p. 57), Los Valles, Mexico; as a Judaizing heretic, Pedro Fernandez

became reconciled in 1647 (ib., vii. 4); Dr. Rodrigo de

Castro, 1550-1629; Dr. Jacob de Castro-Sarmento, F.R.S., 1691-1761;

David de Abraham de Castro-Tartas (often spelled "de Crasto),"

noted printer in Amsterdam, seventeenth century. The only branch of

the family of which it is possible to make a definite pedigree is

the Dutch, as follows:

She says she met her husband, Security Forces Commander Tony Castillo, Jr., in El Paso, Texas, when he was already an active duty member in the Air Force, and they got married in 2000. She was born in Juarez, Mexico, but moved with her family to El Paso when she was 16.

She says she met her husband, Security Forces Commander Tony Castillo, Jr., in El Paso, Texas, when he was already an active duty member in the Air Force, and they got married in 2000. She was born in Juarez, Mexico, but moved with her family to El Paso when she was 16.

F

F "

"

h

h essons

I learned from Bobbie’s life are how fragile life is -to .love your

friends and family for none of us lives forever and tomorrow is not a

guarantee.

essons

I learned from Bobbie’s life are how fragile life is -to .love your

friends and family for none of us lives forever and tomorrow is not a

guarantee.

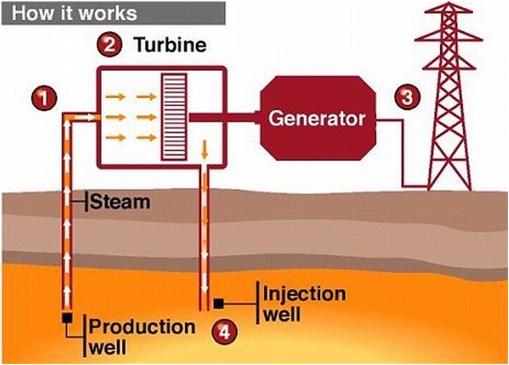

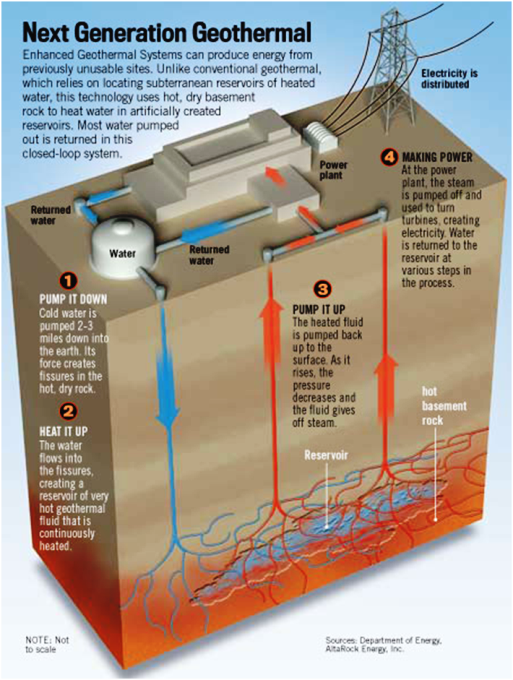

The

most recent big event was the achievement of commercial operations

this month at its Plant 2 in the Olkaria III complex in Naivasha,

Kenya. The commercial operation of this plant boosts Ormat’s total

electricity-generating capacity by 36MW to 611WM worldwide. In 2014,

Ormat will bring a third plant online in Kenya, which should add

another 16MW of capacity. Even better, Ormat has a 20-year power

purchase agreement with Kenya—so there’s a guaranteed market for

this. And it’s got the capital to meet its Kenya ambitions, too: the

Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), which already provided

Ormat with $265 million to build its first two plants in Kenya, will

provide another $45 million for the third plant. As of March 31, 2013,

the company had available committed lines of credit with commercial

banks aggregating $440.9 million, of which $152.9 million was unused.

The

most recent big event was the achievement of commercial operations

this month at its Plant 2 in the Olkaria III complex in Naivasha,

Kenya. The commercial operation of this plant boosts Ormat’s total

electricity-generating capacity by 36MW to 611WM worldwide. In 2014,

Ormat will bring a third plant online in Kenya, which should add

another 16MW of capacity. Even better, Ormat has a 20-year power

purchase agreement with Kenya—so there’s a guaranteed market for

this. And it’s got the capital to meet its Kenya ambitions, too: the

Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), which already provided

Ormat with $265 million to build its first two plants in Kenya, will

provide another $45 million for the third plant. As of March 31, 2013,

the company had available committed lines of credit with commercial

banks aggregating $440.9 million, of which $152.9 million was unused.

The United States Hispanic Chamber of Commerce (USHCC) announced David Gomez, President and CEO of David Gomez & Associates, as Board Convention Chairman of the 2013 USHCC National Convention. The annual event is the largest gathering of Hispanic business leaders in America and a forum to address the most important challenges and opportunities affecting our nation’s small business community. The Convention will take place September 15-17 in Chicago, IL.

The United States Hispanic Chamber of Commerce (USHCC) announced David Gomez, President and CEO of David Gomez & Associates, as Board Convention Chairman of the 2013 USHCC National Convention. The annual event is the largest gathering of Hispanic business leaders in America and a forum to address the most important challenges and opportunities affecting our nation’s small business community. The Convention will take place September 15-17 in Chicago, IL.

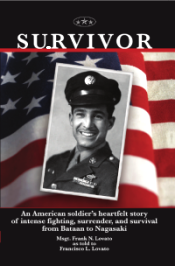

"SURVIVOR"

is a dynamic and emotional account of one of the most tragic periods

in American history. Told through the eyes and soul of Frank Lovato to

his son, Francisco Lovato, a retired psychotherapist, the story leaps

from tears to cheers as Frank and his buddies survive the travails of

being a formidable combatant and subsequently a POW of the Japanese in

WWII. Amazingly, Frank, two other Americans and 25 Filipino troops

were the first to engage the invading Imperial Japanese forces of

General Masaharu Homma on the beaches of Northern Lingayen Bay on

December 22, 1941. This fact, virtually lost to the history books,

tells of how MacArthur had positioned most of his forces over 45 miles

away from where the 44,000 Japanese actually landed. Frank's 4 half

track battery, equipped with 75-mm cannons sunk approximately 30

Japanese landing craft before pulling off the beach as Japanese

troops, who had landed farther northward attempted to surround them.

REVIEWS "SURVIVOR" is many things at once-a warrior's story;

and epic of endurance and survival; an insider's account of the Bataan

tragedy; and above all an act of filial fealty by Francisco Lovato who

has established in this narrative his father's rightful place as an

authentic American hero." Peter Collier- NY Times Bestselling

biographer-Kennedy's, Rockefellers,Fords,Roosevelts "In this

feelingly told biography, Lovato and his son honor that most essential

imperative of all wars-which is simply to remember, no matter how

painful the memories may be. SURVIVOR is a vivid memoir of resilience,

sacrifice, and courage." Hampton Sides -Author of Ghost Soldiers

"SURVIVOR"

is a dynamic and emotional account of one of the most tragic periods

in American history. Told through the eyes and soul of Frank Lovato to

his son, Francisco Lovato, a retired psychotherapist, the story leaps

from tears to cheers as Frank and his buddies survive the travails of

being a formidable combatant and subsequently a POW of the Japanese in

WWII. Amazingly, Frank, two other Americans and 25 Filipino troops

were the first to engage the invading Imperial Japanese forces of

General Masaharu Homma on the beaches of Northern Lingayen Bay on

December 22, 1941. This fact, virtually lost to the history books,

tells of how MacArthur had positioned most of his forces over 45 miles

away from where the 44,000 Japanese actually landed. Frank's 4 half

track battery, equipped with 75-mm cannons sunk approximately 30

Japanese landing craft before pulling off the beach as Japanese

troops, who had landed farther northward attempted to surround them.

REVIEWS "SURVIVOR" is many things at once-a warrior's story;

and epic of endurance and survival; an insider's account of the Bataan

tragedy; and above all an act of filial fealty by Francisco Lovato who

has established in this narrative his father's rightful place as an

authentic American hero." Peter Collier- NY Times Bestselling

biographer-Kennedy's, Rockefellers,Fords,Roosevelts "In this

feelingly told biography, Lovato and his son honor that most essential

imperative of all wars-which is simply to remember, no matter how

painful the memories may be. SURVIVOR is a vivid memoir of resilience,

sacrifice, and courage." Hampton Sides -Author of Ghost Soldiers

With Memorial Day coming up it will be good for Americans to remember

all of our Veterans. Then on NOV 11 this year we will continue

to honor our men and women on the 50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War.

With Memorial Day coming up it will be good for Americans to remember

all of our Veterans. Then on NOV 11 this year we will continue

to honor our men and women on the 50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Records

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Records

Case file numbers were updated to reflect subsequent journeys to

and from the United States. For example, if you know that your

ancestor first immigrated to the United States in 1910, left to

visit family in 1920 and came back for good in 1921, the case file

number may have been changed accordingly. You would need to find

the passenger list from 1921 and follow the above steps.

Case file numbers were updated to reflect subsequent journeys to

and from the United States. For example, if you know that your

ancestor first immigrated to the United States in 1910, left to

visit family in 1920 and came back for good in 1921, the case file

number may have been changed accordingly. You would need to find

the passenger list from 1921 and follow the above steps.

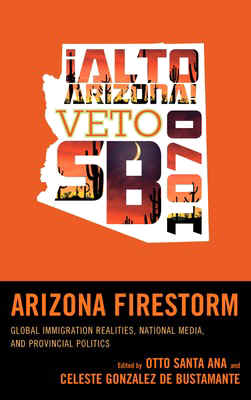

Small towns are like big barrios. People know and take care of each other. Which is why Arizona’s mining communities impress me greatly. That, and the people they produce. Some are two towns separated by a hyphen—Hayden-Winkelman, Globe-Miami, Clifton-Morenci—but for all practical purposes they are one community.

Small towns are like big barrios. People know and take care of each other. Which is why Arizona’s mining communities impress me greatly. That, and the people they produce. Some are two towns separated by a hyphen—Hayden-Winkelman, Globe-Miami, Clifton-Morenci—but for all practical purposes they are one community. These towns are proud of their own. In Hayden, pictures of all the graduating classes are displayed on the walls of the high-school gym. Miami converted its old elementary school, the Bullion Plaza school, into a local history museum, which chronicles the town’s history. The contributions of the union stand out as does the memorabilia of local veterans—many of them decorated heroes—who fought in WW II, Korea, and Viet Nam.

These towns are proud of their own. In Hayden, pictures of all the graduating classes are displayed on the walls of the high-school gym. Miami converted its old elementary school, the Bullion Plaza school, into a local history museum, which chronicles the town’s history. The contributions of the union stand out as does the memorabilia of local veterans—many of them decorated heroes—who fought in WW II, Korea, and Viet Nam. The headquarters of the historic 1983 strike that pitted the Clifton-Morenci copper miners against Phelps

Dodge and Democratic Governor Bruce Babbitt was the Morenci Miners United Steelworkers Local 616 Union Hall in Clifton. After the strike the union moved, and the hall was bought by Jeff Gaskin, who converted it into a museum of the union and the 1983 strike. A mural that chronicles the strike takes up one entire wall. The community’s pride in the history of the union and the unionists is impressive and moving.

The headquarters of the historic 1983 strike that pitted the Clifton-Morenci copper miners against Phelps

Dodge and Democratic Governor Bruce Babbitt was the Morenci Miners United Steelworkers Local 616 Union Hall in Clifton. After the strike the union moved, and the hall was bought by Jeff Gaskin, who converted it into a museum of the union and the 1983 strike. A mural that chronicles the strike takes up one entire wall. The community’s pride in the history of the union and the unionists is impressive and moving. Alfredo Gutierrez is from Miami. First elected to the Arizona senate at age 25, Alfredo served as the majority and minority leader in the state senate. During the 1970s, as the Senate Majority Leader, Alfredo was arguably the state’s most powerful elected official.

Alfredo Gutierrez is from Miami. First elected to the Arizona senate at age 25, Alfredo served as the majority and minority leader in the state senate. During the 1970s, as the Senate Majority Leader, Alfredo was arguably the state’s most powerful elected official. I’m proud to be from Douglas also and to have worked alongside the two Tonys described above.

And Arizona’s first, and only, Mexican American Governor, Raúl Castro, is from Douglas.

As Dr. Christine Marín says: “Mining town kids: they love us or they hate us in Arizona…because we’re everywhere!”

I’m proud to be from Douglas also and to have worked alongside the two Tonys described above.

And Arizona’s first, and only, Mexican American Governor, Raúl Castro, is from Douglas.

As Dr. Christine Marín says: “Mining town kids: they love us or they hate us in Arizona…because we’re everywhere!”

At the time that the walled fort was built(possibly

1853), a sundial was set above the portals of

the entrance gate. The sundial has a story that goes with it.

At the time that the walled fort was built(possibly

1853), a sundial was set above the portals of

the entrance gate. The sundial has a story that goes with it. In

1828, don Jesus Treviño purchased approximately half of the Vasquez

Borrego land grant. The township of San Ygnacio was to be built on

this land grant by a few landowners and the workers they brought with

them from Mexico. In the beginning, both the patrons and the workers

had to endure the same hardships in this untamed land. The first signs

of civilization was when Don Jesus erected the

In

1828, don Jesus Treviño purchased approximately half of the Vasquez

Borrego land grant. The township of San Ygnacio was to be built on

this land grant by a few landowners and the workers they brought with

them from Mexico. In the beginning, both the patrons and the workers

had to endure the same hardships in this untamed land. The first signs

of civilization was when Don Jesus erected the  Don

Blas Maria, born from the third marriage, was very instrumental in

building of San Ygnacio. To bring story of San Ygnacio we go

back to the founding of the Dolores Vista on the Texas side of the Rio

Grande and the mouth of the Arroyo Dolores. Don Jose Vasquez Borrego,

owner of a large ranch, San Juan del Alamo, in Monclova, Coahuila was

granted approximately 110,000 acres for starting the Vista at Dolores.

The settlement started with about 15 families and in 1753, don Jose

Vasquez Borrego was granted approximately 110,000 acres more. These

220,000 acres of land covered from the Arroyo Dolores to the present

day Ramireño north fence and from the river approximately 40 miles to

the northeast.

Don

Blas Maria, born from the third marriage, was very instrumental in

building of San Ygnacio. To bring story of San Ygnacio we go

back to the founding of the Dolores Vista on the Texas side of the Rio

Grande and the mouth of the Arroyo Dolores. Don Jose Vasquez Borrego,

owner of a large ranch, San Juan del Alamo, in Monclova, Coahuila was

granted approximately 110,000 acres for starting the Vista at Dolores.

The settlement started with about 15 families and in 1753, don Jose

Vasquez Borrego was granted approximately 110,000 acres more. These

220,000 acres of land covered from the Arroyo Dolores to the present

day Ramireño north fence and from the river approximately 40 miles to

the northeast.

The Long House.

The Long House.

Rene Vellanoweth of Cal State L.A. shows a cave on San Nicolas

Island where it's believed the Native American woman who came to be

known as the Lone Woman of San Nicolas lived from 1835 to 1853. Navy

archaeologist Steve Schwartz had searched the island for the cave for

20 years without success.

Rene Vellanoweth of Cal State L.A. shows a cave on San Nicolas

Island where it's believed the Native American woman who came to be

known as the Lone Woman of San Nicolas lived from 1835 to 1853. Navy

archaeologist Steve Schwartz had searched the island for the cave for

20 years without success.