|

ccording

to the 2010 Census, the total population of the United States was

305,305,818. The count for the Hispanic population of the United States

was 50,477, 594, not counting the almost 5 million Puerto Ricans on the

island. That would bring the Hispanic count to almost 55 million.

Hispanic Heritage Month is not about celebrating the heritage of

Spain and other Hispanic identified countries in the Americas and

elsewhere. Hispanic Heritage Month celebrates the contributions to the

United States by Spain and other Hispanic identified countries in the

Americas and elsewhere. That’s a critical distinction. Unfortunately,

many Non-Hispanic Americans know little about the contributions to

American life and culture by American Hispanics; that is, those

Hispanics in the United States who are citizens of the United States

either by birth or naturalization and, therefore, not (necessarily)

citizens of Hispanic countries in the Americas and elsewhere. There are

some instances where American Hispanics like other groups have dual

citizenship.

Another

way to differentiate U.S. Hispanics from Hispanics in Spain and other

Hispanic identified countries in the Americas and elsewhere is to think

of the latter as Hispanic Americans and the former as American

Hispanics. American Hispanics live and work legitimately in the United

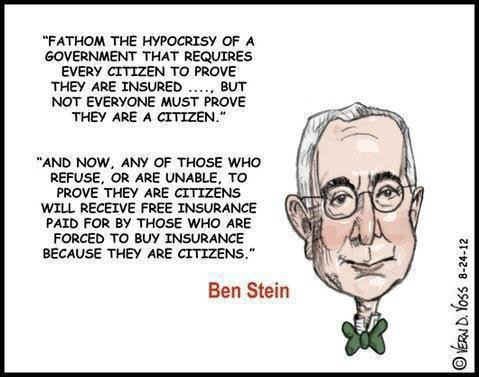

States. There are some Hispanics like members of other groups living and

working in the United States legitimately with temporary documentation

(Green Cards) while waiting to become American citizens. Those Hispanics

who live and work in the United States without proper documentation are

not considered American Hispanics. They are sometimes referred to as

“undocumented workers.”

Celebrating

the Hispanic heritage of the United States actually started in 1967 with

a proclamation by President Lyndon Baines Johnson recognizing the 16th

of September of that year as Hispanic Heritage Day. The 16th

of September is celebrated in Mexico and by Mexican Americans in the

United States as Mexican Independence Day from Spain in 1821. The

following month the President’s Cabinet (Inter-agency) Committee on

Mexican Americans held a Mexican American summit in El Paso, Texas (see

“Minority on the Border,” The Nation, 12/7/67 by the author). On September 17, 1968, House

Joint Resolution 1299 (Public Law 90-498) was passed unanimously by

voice vote proclaiming the week of September 15-22 as Hispanic Heritage

Week. Subsequent presidents continued the tradition. On August 17, 1988

Air Force Colonel Gil Coronado successfully persuaded Congress to enact

Public Law 100-42 designating National Hispanic Heritage Month from

September 16 to October 15, spanning celebration of September 16th

and Dia de la Raza (Columbus Day) on October 12. National Hispanic

Heritage Month coincides with the independence days of Costa Rica, El

Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Chile also.

Little

known because American textbooks exclude it, the Hispanic heritage of

the United States is older than the Anglo Heritage of the United States.

By the time of the Plymouth Plantation in 1619, Saint Augustine

(Florida) had been in existence for 55 years, and Santa Fe was already a

thriving city. Throughout the vast expanse of the Spanish presence in

North America, Spanish settlements of varying sizes dotted the

landscape. Spanish exploration in what is now the United States took

many forms. In 1536 Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca left for us a record of

his travels through Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico. And in 1592, Gaspar

Pérez de Villagrá recorded in Virgilian cantos the exploits of the

Spaniards at Acoma Pueblo near present-day Albuquerque. That text, Historia

de Nuevo Mexico, is now regarded

as the first American epic. Over time, Santa Fe became the

commercial center of Spain in what is now the United States and

geographically critical in the westward expansion of the United States

in what was known as “the Santa Fe Trail.”

hat

is the term “Hispanic”? What does it mean? Where does it come from?

Why is it used to identify particular peoples of the Americas? Is the

term “Hispanic” the same as “Latino”? Both the terms

“Hispanic” and “Latino” have been used for some time. More

recently, however, the revivified term “Latino” has resonated with

contemporary American Hispanics, many of whom perceive the term

“Hispanic” as a label imposed on them by the bureaucracy of the U.S.

Census Bureau. Actually, the term “Hispanic” cropped up in the early

Spanish colonial period to designate persons with a biological tie to a

Spaniard. In Spanish the term was “Hispano.” Later, the term evolved

into “Hispano- Americano” to emphasize that Hispanos were also

Americans since they were of the Americas. Historically, the United

States appropriated that term for its own identity so that few Americans

realize that all the populations of the Americas are Americans.

The

word “Hispanic” is one of those large rubrics like the word Catholic

or Protestant. By itself, the word refers to all Hispanics

(persons whose heritage derive from historical origins in Hispania--

Roman name for Spain), attesting to a common denominator, conveying

information that the individual is an off-spring or descendent of a

cultural, political or ethnic blending which included in the beginning

at least one Spanish root either biological or linguistic or cultural.

That means a Mexican Indian with no Spanish “blood” (as we

understand that term) in him or her, but who speaks Spanish and has

amalgamated, internalized, or assimilated the evolutionized Spanish

culture of Mexico is considered an Hispanic just as an Indian of the

United States who speaks English and has amalgamated, internalized, or

assimilated the evolutionized Anglo culture of the United States is

considered to be an American though in the case of American Indians they

are Americans both by priority (they were here first) and by fiat (the

United States made them Americans by colonization and later by law).

Talking

about people in terms of labels can be misleading. For example, a person

may be an Hispanic in terms of cultural, national or ethnic roots.

Nationally Colon (Columbus) was a Spaniard though born in Genoa when

it was part of the Spanish empire. Werner Von Braun (father of the

American space program) was born in Germany and became an American

citizen after his relocation to the United States from Nazi Germany. In

Argentina there are Hispanics who have no “Spanish blood” but who,

nevertheless consider themselves Hispanics, speak Argentine Spanish and

are fluent in Italian or German, the languages of their immigrant

forebears to that country.

Put

another way, the term “Hispanic” is comparable to the term Jew

which describes the religious orientation of people who may be

ethnically Russian, Polish, German, Italian, English, etc. There are

Chinese Jews, Ethiopian (Falashan) Jews, Indian Jews, et al. So too the

term “Hispanic” describes people

by linguistic orientation (Spanish speakers from countries whose

principal or national language is Spanish). In the Americas there are

more speakers of Spanish than English. These may be Mexicans,

Nicaraguans, Cubans, Venezuelans, Chileans, Argentines, et al.

Additionally, there are blended Hispanics often identified as

Indo-Hispanics and Afro-Hispanics, Asian-Hispanics (including Filipinos)

and a congeries of other mixtures. There are Hispanics who identify

themselves as Black and many who identify themselves as White. There is

an array of Chinese Hispanics, Lebanese Hispanics, Pakistan Hispanics,

Hindu Hispanics, Jewish Hispanics (Sephards) et al. This all points to

the fact that Hispanics are far from a homogeneous group. In the main,

though, their common characteristics are language (Spanish or a

derivative version of Spanish as well as a distinctively derivative version

of English oftentimes called Spanglish) and religion (most are

Catholic), though there is a growing number of Hispanic Protestants).

There are other lesser characteristics as well.

ccording

to current demographic data, the United States has the 5th

largest Hispanic population in the world exceeded only by Mexico,

Spain, Columbia, and Argentina. By the year 2015 only Mexico will have a

larger Hispanic population. In the year 2000, close to 7 million

American Hispanics who reported themselves as such in the Census lived

in the Los Angeles metropolitan area, another 3 million in New York

City. Since 1980 the American Hispanic population of both cities almost

doubled. And over the 1990's the Hispanic population of the United

States grew 58%. Since 1980 Mexican Americans almost doubled their

population size. From 24 million American Hispanics in 1990, the 2010

Census enumerated 50.5 million U. S. Hispanics not counting the

4.5 million Hispanics in Puerto Rico who are excluded from the

count. In the 1990 count almost 4 million Hispanics in the United States

were missed by the Census , and another 4 million or so undocumented

Hispanics in the United States.

At

the start of the new millennium there were about 45 to 48 million

Hispanics in the United States, making them the single largest minority

group in the country. That is, 16% of the U.S. population was Hispanic.

Or, 1 in 6 was Hispanic. As a group, American Hispanics are larger than

the population of Canada (32 million) and more than twice that of

Australia (20 million). Projections suggest that by the year 2050 1 in 3

Americans will be Hispanic. Peter Francese of American Demographics

notes that “America really had no clue that the Hispanic population

was that big.” But Steven Murdoch, the Texas demographer, has been

aware of the growth of the Hispanic population in Texas. He has forecast

that by the year 2040 Hispanics in Texas (Tejanos) will comprise 65% of

the state’s population while the Anglo population of the state will

have dwindled to 25%. Ten percent of the state’s population will be

black or other.

According

to the 2010 Census, the Hispanic population grew from 35.3 million to

50.5 million (not counting Island Puerto Ricans). Per the U.S. 2010

Census count, Hispanics are in every state of the country. One report

asserts that Hispanics are in every county of the United States.

Hispanics make up the majority population in 28 major U.S. cities with

more than 100,000 inhabitants, most of them located in California,

Texas, Florida, and New Jersey. The Hispanic population more than

doubled in Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and South Carolina.

75% of Hispanics live in Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida,

Illinois, New Mexico, New Jersey, New York, and Texas. Five states are

15% or more Hispanic (New Mexico, 46.3%; California, 31%; Texas, 30%;

Arizona, 22%; Nevada, 15%) and

five states are 10% or more Hispanic (Colorado, 14%; Florida, 14%; New

York, 14%; New Jersey, 12%; Illinois 10%). Nine states and the District

of Columbia are 5% or more Hispanic (Connecticut, 8%; Idaho, 7%; Utah,

7%; DC, 7%; Wyoming, 6%; Washington, 6%; Oregon, 6%; Massachusetts, 6%;

Rhode Island, 6%; Kansas, 5%). Five states account for almost 75% of the

U.S. Hispanic population (California, 34%; Texas 20%; Massachusetts,

9%; Florida, 7%; Illinois, 4%. These figures don’t take into account

Census errors like the one in 1970 which failed to count some 3 million

Mexican Americans. One of the reasons for so much difficulty in counting

American Hispanics is that a significant

number report themselves

as White or Black, not Hispanic.

In the 20th century, the U.S. Hispanic population grew

5 times faster than the overall population. Since 1980, the nation’s

Hispanic population has grown by more than 40% compared to 7% for the

overall population. At present growth rates, the American population is

expected to reach 325 million by the year 2020. Projecting the U.S.

Hispanic figures per their growth rates, they could number well over 60

million by the year 2020. That means that about 1 in 5 Americans could

be Hispanic, roughly 20% of the U.S. population. (Counting Puerto Rico,

the U.S. Hispanic population today is about 54.2 million—17.4% of the

total U.S. population.) By the year 2050 some demographic forecasts

expect the U.S. Hispanic population to triple. At the moment,

Hispanics account for more than half of the U.S. population

growth. Astonishingly, these growth rates are not fueled

principally by immigration but by fertility. An extreme projection by

the U.S. Census Bureau suggests

that by the year 2097, 50% of the entire U.S. population will be

Hispanic, 30% will be black; 13% will be Asian, and only 5% will be

white.

In

a 1988 study, the Arizona Republic of Phoenix indicated that

in the year 2013 “Hispanics will make up nearly half of Arizona’s

population, raising the prospect of their taking a strong leadership

role in the state.” Despite these auguries for the population growth

of American Hispanics, little planning if any has been undertaken for

such an eventuality. In fact, compared to their size in the American

population, American Hispanics are grossly underrepresented in most

areas of American public life and policy. Like Blacks, they are

congregated in the gladiatorial areas of sports. Despite their looming

size, American Hispanics are almost never seen on mainstream network

television news shows as hosts or discussants on American domestic and

foreign policy issues. Except for special shows, American Hispanics are

still largely invisible in the plethora of inane television programs. In

film, non-Hispanics portray Hispanics (often badly). Many times in film

and television Hispanics are often referred to by Hispanic names in the

scripts, but never seen.

ho

are these people whose presence in the American population will have

such a major force in the American future? Surprisingly, most Americans

tend to think of U.S. Hispanics as a loose aggregation of

“immigrants” who speak only Spanish, somewhat aware that the

largest number of them live in the Southwest, a fair number in the

Mid-West, the Upper Middle Atlantic states and New England with a

growing number in the American Southwest.

Essentially, American Hispanics may be sorted into five groups:

(1) Mexican Americans, many of whom identify themselves as Chicanos, an

ideological designation that identifies their generation, (2) Puerto

Ricans, some of whom identify themselves as Boricuas, (3) there are U.S.

Hispanics who identify themselves as Hispanos

(found mostly in New Mexico many of whom identify themselves as Manitos

and are counted as Mexican Americans; in Texas a vast number if not most

Mexican Americans refer to themselves as Tejanos;

and in California, many Hispanic Californians who are descendents of the

founding families in both Baja and Northern California refer to

themselves as Californianos

rather than Mexicans, (4) Cuban Americans, and (5)

Latinos–-Hispanics from countries other than Mexico, Cuba, Spain, and

Puerto Rico. A recent PEW Hispanic Center Report,

When Labels Don’t Fit, explained that “only about one-quarter

(24%) of Hispanic adults say they most often identity themselves by

“Hispanic” of “Latino,“ adding that “about half (51%) say they

identify themselves most often by their family’s country or place of

origin—using such terms as Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, Salvadoran of

Dominican.”

Per the U.S. Census Count of 2010 the Mexican origin population

grew by 54% and accounts for 63% of U.S. Hispanics, about 32 million.

Two out of three U.S. Hispanics are Mexican Americans. Not counting

Puerto Rico, Puerto Ricans make up almost 10% of U.S. Hispanics with

almost 4 million of them in the continental U.S. Almost 4 million of

them live on the island of Puerto Rico. Mexican Americans and Puerto

Ricans make up almost 75% of the U.S. Hispanic population. In other

words, 3 out 4 U.S. Hispanics are Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans.

The almost 2 million Cuban Americans in the United States, most of

them in Florida, make up about 4% of U.S. Hispanics. Latinos, about 12

million of them with roots in Latin America make up the balance of U.S.

Hispanics—25%. In other words, 1 out of 4 U.S. Hispanics is Latino,

that is, from countries other than Mexico, Puerto Rico, or Cuba. There

are other U.S. Hispanic groups, statistically not significant as groups,

like Sephardic Americans (Hispanic Jews), Pacific Islanders with

Hispanic roots, and American Filipinos who are not counted as Latinos

but should be since Spain had a longer presence in the Philippines than

in Mexico.

In

profile, U.S. Hispanics are a “young” population with a median age

in 2010 of 27 years compared to 34 years for non-Hispanics. Hispanics

are predominantly an urban population: 82% live in cities, compared to

65% of Anglos, though there is a trend of U.S. Hispanics migrating to

rural areas. In terms of median income, in 2000, U.S. Hispanics earned

an average of $23,300, some $2,450 more than blacks but some $2,600 less

than Anglos. In 2010 median income for U.S. Hispanics was $40,200.

Nearly 1 out of every 4 American Hispanics fell below the poverty level

in 1999, more than thrice the ratio for Anglos. In 2000, American

Hispanic unemployment rose to 13.8% compared to 7.2% for the total

population. In 2010 Hispanic unemployment rose to 18% compared to 9.6%

for the total population. While there were gains for some American

Hispanics, most of these figures remained relatively unchanged in the

year 2010 for the mass of American Hispanics who are still searching for

America. Economic projections indicate that by 2012 Hispanics will

represent a $1.3 trillion consumer market. In 2010, $21.3 billion in remesas

(money sent to Mexico) were generated by Mexicans working in the

United States.

mportantly,

American Hispanics are not recently arrived immigrants to the United

States. Given the finite immigration quotas for “Latin America”

since 1924, the present population of U.S. Hispanics would not be as

large if its source of growth were solely from immigration. Their sheer

size in the American population points to the fact that American

Hispanics are of longer duration in the United States and their growth

stems principally from fertility. According to the National Center for

Health Statistics, in 2010 there were 98.8 births for every 1000

Hispanic women compared to 66 births per 1000 Anglo women.

The

initial core of Hispanics in the U.S. population came from the Dutch

colony of New Amsterdam, later renamed New York after the British

acquired it in the 17th century. Later the Hispanic Jews

(Sephardim) who came with the Dutch colony contributed significantly to

the colonial revolutionary efforts of 1776 and to the later prosperity

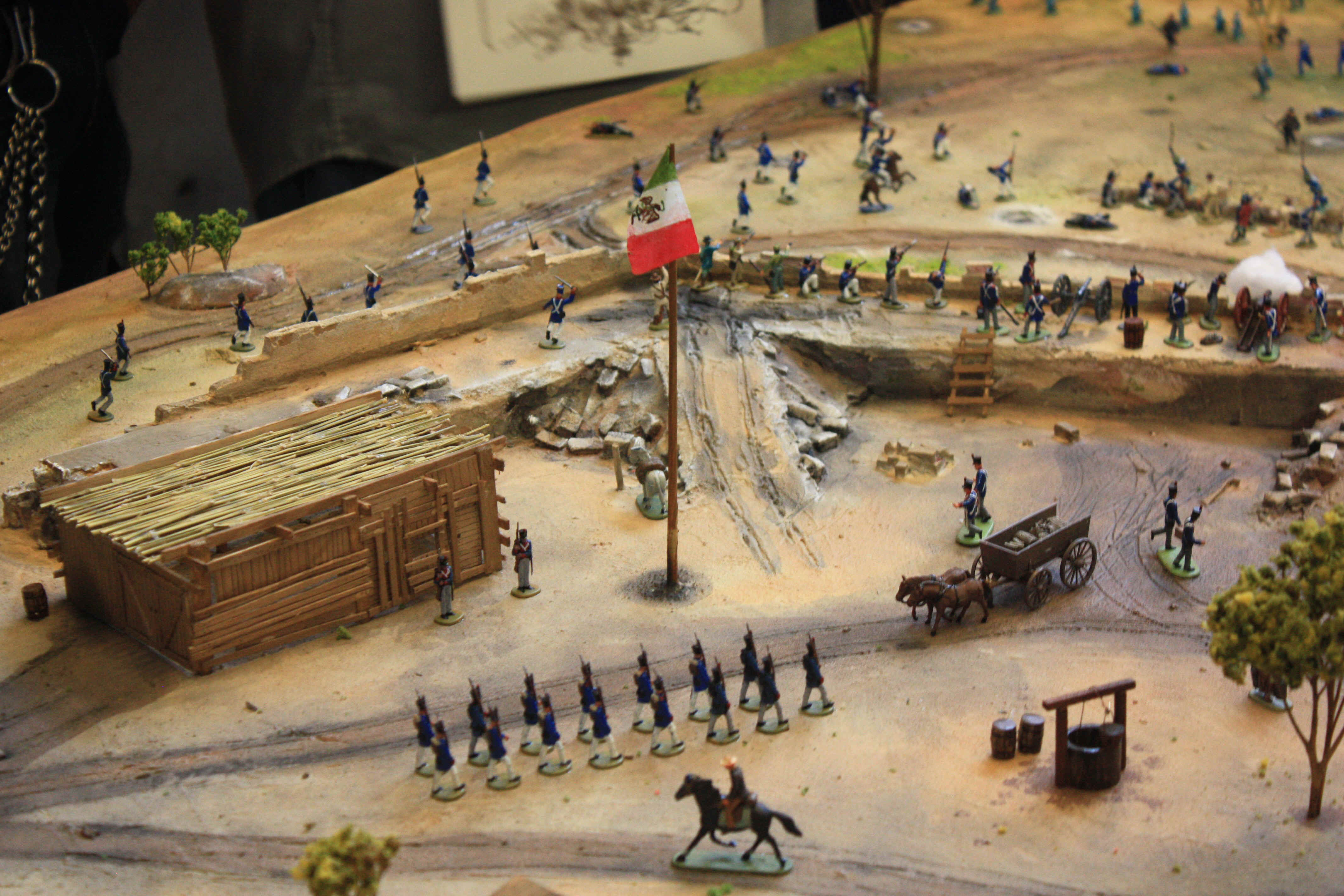

of the country. In the 19th century, in two swift “gains”

within 50 years of each other, the United States “acquired” a

sizable chunk of its Hispanic population, not counting the acquisition

of Louisiana in 1803 with its Hispanic residents and Florida in 1819

with its Hispanic population. The first “gain” was as a consequence

of the U.S. war against Mexico (1846-1848) out of which came the Mexican

Americans of California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico,

Texas, parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. No one is sure of the

numbers of ”Mexicans” who came with the dismembered territory

(almost half of Mexico’s domain) but figures range from 150,000 on the

low side to as many as 3.5 million (including Hispanicized Indians). The

second “gain” of Hispanics occurred as a result of the U.S. war with

Spain (1898) out of which came the Puerto Ricans, Filipinos, Guamanians,

Virgin Islanders, and the first wave of Cubans (though Cubans had been

emigrating to the American colonies first then the United States since

the 17th century. In 1917 Cuba was cut loose by the United

States. The figures for these groups range variously as well. But the

point is that American Hispanics have been part of the United States

historically for some time. In both the U.S. war with Mexico and the

U.S. war with Spain, the United States “came” to the Hispanics, the

Hispanics did not come to the United States. They were already on their

land which the United States appropriated from them as a spoil of war.

In both cases, Hispanics who came with the conquered territories were

chattels of war. Unfortunately, Americans have tended to think of

Hispanics in the United States as newly arrived and to confuse them with

Hispanic Americans, the 400 million who populate the Spanish-language

countries of the American hemisphere.

Not

all American Hispanics agree on the term Hispanic or Latino to identify

themselves. Many American Hispanics from the Southwest, for example,

prefer to be called Mexican Americans or Chicanos and think the term

Hispanic is an arbitrary label imposed on them by a bureaucracy with a

colonial mentality. Sandra Cisneros eschews the term Hispanic; she

favors the term Latina. Many Puerto Ricans agree with that sentiment and

prefer to be called Boricuas or Latinos. Other American Hispanics

contend the term Hispanic dilutes their individual identities as, say,

Salvadorans, Nicaraguans, etc. At best, the term Hispanic is a

convenient way to talk about a diverse group of people much the way we

use the term American to talk about an equally diverse group of people.

In vogue now with many Hispanics in the Southwest and elsewhere is the

term Latino which could very well include Italians and other groups with

links to Roman Latinization.

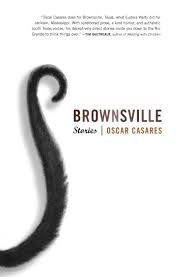

This

“looking for a name” has created particular problems for American

Hispanics, especially in libraries (including the Library of Congress)

and with bookstores and booksellers. Irma Flores Manger, an Austin

librarian, thinks

we are leaving a whole group of people in limbo without any positive

literature about Chicanos or other Latino experiences in which the only

books available are written by authors in English. The books are

not available in some libraries because if you are not familiar with the

authors you will not buy the books as librarians. The book stores

usually have a small section on Latino Studies and sometimes our books

are lumped in with immigration studies. I don't why it's so hard

for these stores to carry books by Chicano or Latino authors in English;

there is usually a huge section for African Americans or Native American

materials.

The

difficulty lies in the fact that indeed Americans (including librarians)

do not really have a handle on the Hispanic taxonomy. For them all

Hispanics are alike. Unlike African Americans who are not lumped in with

Africans, American Hispanics are lumped in with Hispanics of Latin

America. The Library of Congress is a good example of this lumping. When

one wants to find material on African Americans in the Library of

Congress one does not go to the African Section. They are found in the

American Section. But to find materials on American Hispanics in the

Library of Congress one has to go to the Hispanic Section where all

other Hispanics are included also. Mostly, American book-stores have

separate sections for African materials and for African American

materials. Not so for American Hispanic materials. All Hispanic

materials are lumped into the Hispanic section. Peddling the Colombian

writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ books in Spanish or English translation

for Chicanos instead of Rudolfo Anaya’s works only strengthens the

proposition that Americans do not differentiate between Hispanics

because they don’t know who Hispanics are.

Admittedly,

there is much to a name. I’m an American Hispanic of Mexican stock who

subscribes to a Chicano perspective of life in the United States. I’m

not an Hispano because I’m not Spanish. And I’m not a Latino because

I’m not from one of those “other” Spanish-language countries of

the Americas. A Puerto Rican friend of mine explains that he’s an

Hispanic of mainland Puerto Rican stock and subscribes to a Boricua

perspective of life in the United States. Another friend of mine tells

me he’s an American Scandinavian of Norwegian stock who is a

registered Republican. I don’t find that confusing at all. We’re all

Americans, rich in cultural, linguistic and ethnic diversity.

What’s in a name? Everything. That’s why my name is Felipe

and my friend’s name is Sean. Names help to tell us apart. They also

reflect our heritage and background. Unfortunately, many Americans tend

to think the word Hispanic refers to a homogeneous group of

people–which it does not, anymore than the word German, say, (as in

German Americans) refers to a homogeneous group of people. American

Hispanics come in all sizes, shapes and colors.

deologically,

Mexican American Chicanos say the term Hispanic diminishes their

demographic priority when “lumped” with other American Hispanic

groups (all of which are considerably smaller than the Mexican American

group). Those Mexican American Chicanos contend that this lumping

suggests that all U.S. Hispanic groups are equal in size and have passed

through the same historical process in the United States, a suggestion

not supported by the facts. Not all U.S. Hispanic groups have passed

through the same historical process as Mexican Americans and Puerto

Ricans. The historical

process of these two groups has been distinctive, not shared by

“other” American Hispanic groups in the United States. A sizable

number of Mexican Americans and all Puerto Ricans are American

territorial minorities by virtue of conquest. For this reason, shrill

groups of Mexican American Chicanos and Puerto Ricans have resented

across the board applications of legal remedies (affirmative action, for

one) for all U.S. Hispanics for historical discrimination they have not

endured nor suffered. Militant members of these groups say that hiring a

U.S. Hispanic of Peruvian

descent, say, to head a major federal program intended to remedy

discrimination against territorial Hispanics does not remedy

discrimination suffered by Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans at the

hands of Anglo-Americans since their conquest and for whom these legal

remedies were originally enacted if such remedies are applied across the

board for all Hispanics whether or not they are members of

the aggrieved

groups. Peruvian culture–while Hispanic–is not Mexican

American culture nor Puerto Rican culture. There are notable linguistic

differences as well.

Additionally,

Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans point out the difference between

an “oppressed” territorial minority (the U.S. came to them) and

“political or economic refugees” (they came to the U.S.) Many

Chicano scholars explain that Hispanics

from Mexico

who gravitate to San Diego, Tucson, El Paso, San Antonio, and

Brownsville are migrating to a part of what once

was their ancestral

homeland until 1845/ 1848 (1853 in Southern Arizona with purchase of

the Gadsen Strip),

now considered “greater Mexico” (previously New Spain). Some

Chicano scholars see this migration as analogous to the migration of

Jews to Palestine, their ancestral homeland. Moreover, those same

Chicanos point out, most Mexicans migrating to the United States are

racially more Indian than Spanish. On their Indian side they are, thus,

autochthonous people, here long before the Niña, the Pinta, the Santa

Maria, and the Mayflower. They are not immigrants. They are of the

Americas, sharing a common bond with the indigenous peoples of the

United States and Canada.

In view of the foregoing, plans for meeting the needs of American

Latinos/Hispanics must take into account their overwhelming reliance

on the English language, and particularly that 15% of the U.S. Hispanic

population which is

monolingual Spanish operant. For them Bilingual Education and

Spanish-language publishing makes sense. What is not clear, however, is

the number of American Hispanics in the population group of 50+

who rely principally on Spanish for communication and Spanish language

publications for news and information. Spanish is the primary language

spoken at home by over 35.5 million people aged five or older. There are

45 million Hispanics who speak Spanish as a first or

second language, as well as six million Spanish students, comprising the

largest national Spanish-speaking

community outside of Mexico. Roughly

half of all U.S. Spanish speakers also speak English "very

well."

The United States is home to the second largest Mexican community

in the world second only to Mexico

itself comprising nearly 22% of the entire Mexican origin population of

the world. Almost 11% of the American population are Mexican

Americans. With the exceptions of Puerto Ricans and Cuban Americans, all

other American Latino groups are significantly less than 1% respectively

of the American population. Despite the numeric significance of Mexican

Americans in the U.S. population, the U.S. Latino population is viewed

by the non-Hispanic American mainstream as flat with all U.S. Latinos

regarded equal in population.

Reaching

the 50 million plus American Hispanic population requires knowledge of

who they are and their centrality in the American future. All the more

reason for Hispanic Heritage Month every day.

Copyright

© 2011 by the author. All rights reserved.

|

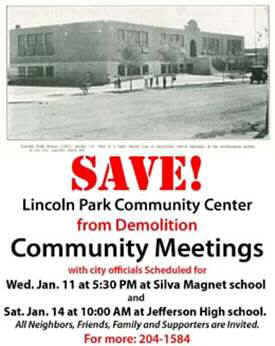

As

the National Association of Hispanic Publications enters it's FOURTH

decade of SERVICE and PROMOTION on the importance, power, and variety

of newspapers, magazines, newsletters, websites, yellow pages, and

more that combine to be Hispanic Print. The Conference was held

October 2-5, 2013 at Disney's Paradise Pier Hotel in Anaheim,

California.

As

the National Association of Hispanic Publications enters it's FOURTH

decade of SERVICE and PROMOTION on the importance, power, and variety

of newspapers, magazines, newsletters, websites, yellow pages, and

more that combine to be Hispanic Print. The Conference was held

October 2-5, 2013 at Disney's Paradise Pier Hotel in Anaheim,

California.

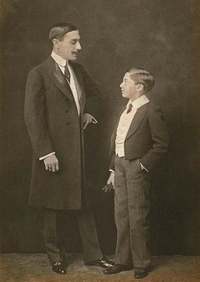

Sam

Dominguez

Sam

Dominguez  Joe

Dominguez

Joe

Dominguez Jose

Mares

Jose

Mares Alfonso

Perez

Alfonso

Perez Charles

Rodriguez

Charles

Rodriguez Jose

Sol

Jose

Sol

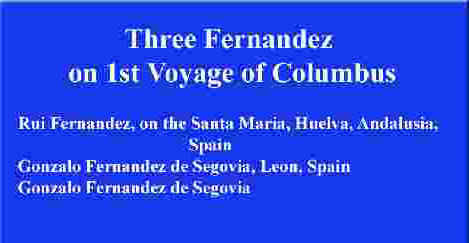

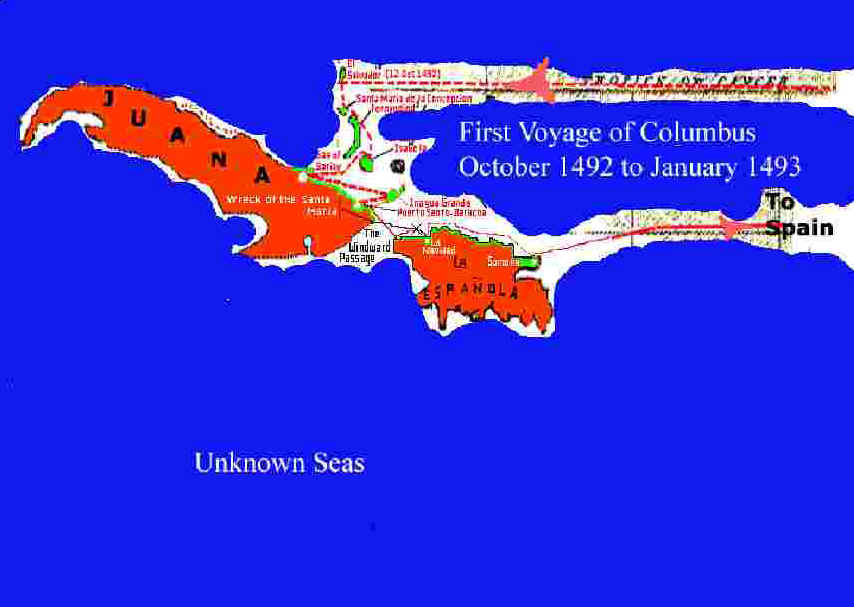

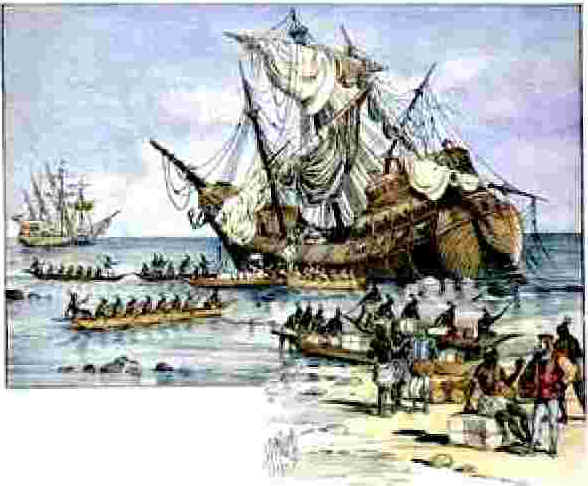

The

Santa Maria could not be repaired. Because all th paniards could not

return home on the smaller Pinta, Columbus had the Santa Maria

dismantled and the lumber used to construct a fort to protect forty

Spaniards, who had to stay behind. The fort was called La Navidad,

because it was built on 25 Dec 1492. It was built near Taino

settlements, not a good idea. The two Gonzalo Fernandez men were left

behind. And Columbus sailed back to Spain in early January 1493. Along

the way back near the islands, he encountered onso Pinzon, who was

very apologetic, and showed Columbus a few pieces of gold he had found

on some of the islands he had explored. They sailed to Spain with

Columbus planning to take Pinzon to court for his mutiny. They got

separated because of very violent storms at sea and arrived at

different places in Spain. Pinzon died almost immediately after

arriving in Spain.

The

Santa Maria could not be repaired. Because all th paniards could not

return home on the smaller Pinta, Columbus had the Santa Maria

dismantled and the lumber used to construct a fort to protect forty

Spaniards, who had to stay behind. The fort was called La Navidad,

because it was built on 25 Dec 1492. It was built near Taino

settlements, not a good idea. The two Gonzalo Fernandez men were left

behind. And Columbus sailed back to Spain in early January 1493. Along

the way back near the islands, he encountered onso Pinzon, who was

very apologetic, and showed Columbus a few pieces of gold he had found

on some of the islands he had explored. They sailed to Spain with

Columbus planning to take Pinzon to court for his mutiny. They got

separated because of very violent storms at sea and arrived at

different places in Spain. Pinzon died almost immediately after

arriving in Spain.

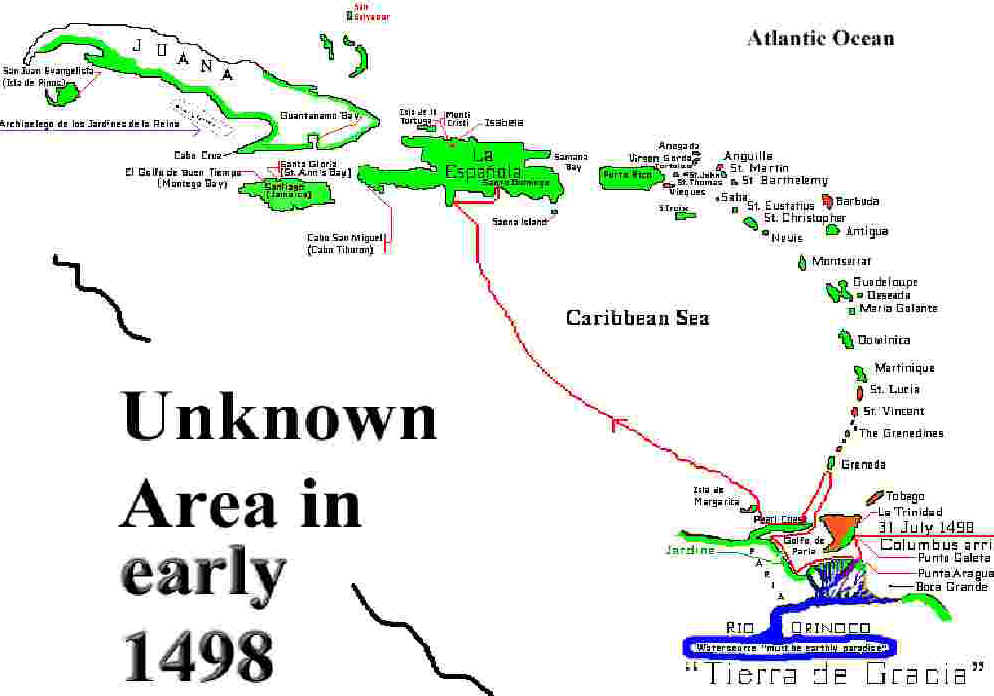

Columbus

sailed from the south, north, northwest, and found many more islands

along the way to La Navidad, and he named them all. He found

cannibals, called Caribs, and the remains of human parts, cooked or

ready to be ooked. It appears that Columbus was very excited about his

discoveries b se his ships sailed west and found some islands, then

northwest and found some more; then north, then northeast, northwest,

and west, then north again, than south, and finally west again. He

discovered about 10 more islands.

Columbus

sailed from the south, north, northwest, and found many more islands

along the way to La Navidad, and he named them all. He found

cannibals, called Caribs, and the remains of human parts, cooked or

ready to be ooked. It appears that Columbus was very excited about his

discoveries b se his ships sailed west and found some islands, then

northwest and found some more; then north, then northeast, northwest,

and west, then north again, than south, and finally west again. He

discovered about 10 more islands.

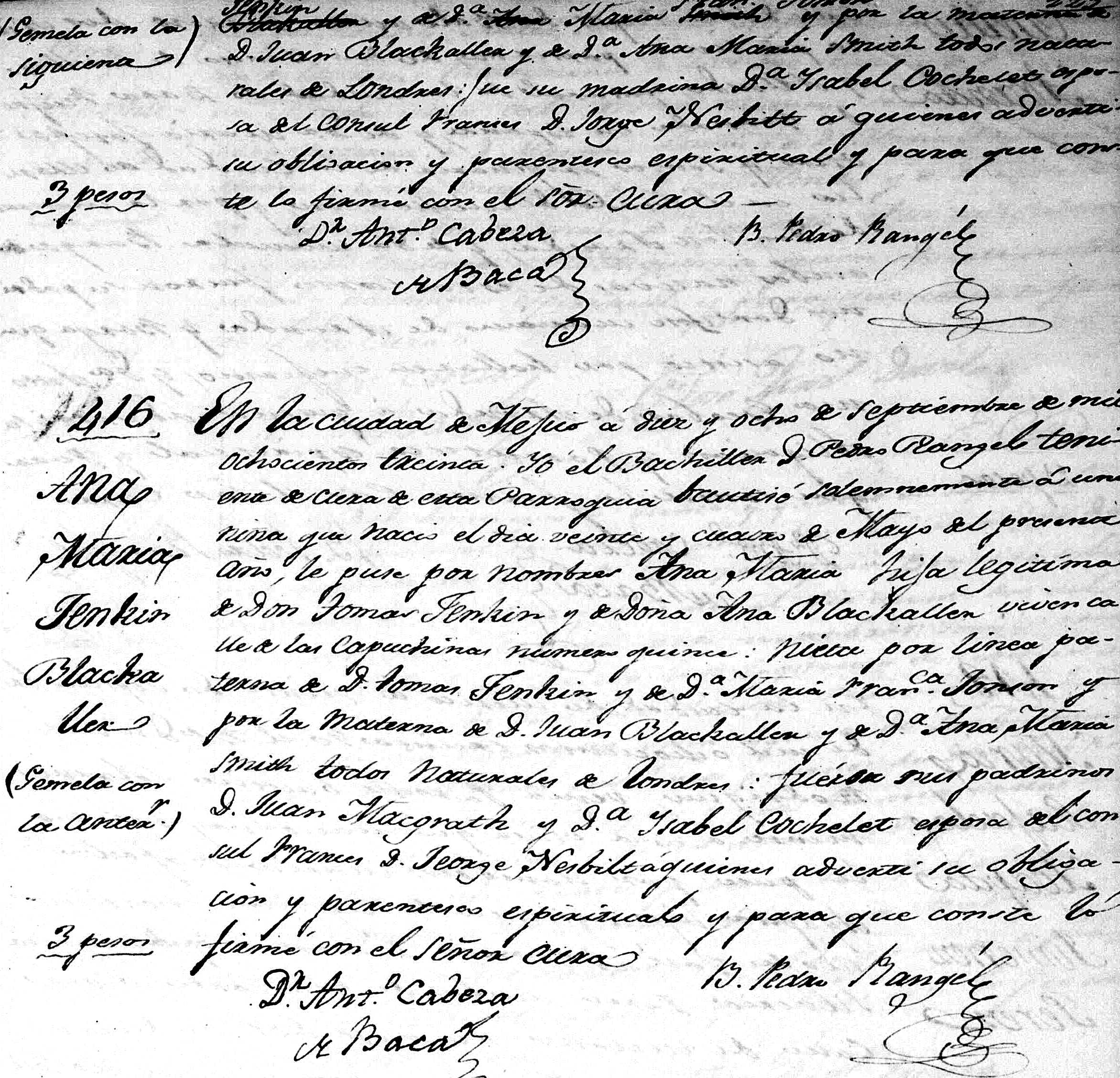

For many Native Americans, the star is a sacred symbol, equated

with honor. The belief is a respected and longstanding tradition,

inherited from their ancestors. The Assiniboine and Lakota Sioux

Indian nations of Eastern Montana and North and South Dakota had a

spiritual belief in the stars, especially in Venus, whose reflected

light made it one of the brightest objects in the night sky with the

appearance of a star. The planet Venus was their guiding star. It

represented the direction from which spirits travel to Earth,

symbolizing immortality.

For many Native Americans, the star is a sacred symbol, equated

with honor. The belief is a respected and longstanding tradition,

inherited from their ancestors. The Assiniboine and Lakota Sioux

Indian nations of Eastern Montana and North and South Dakota had a

spiritual belief in the stars, especially in Venus, whose reflected

light made it one of the brightest objects in the night sky with the

appearance of a star. The planet Venus was their guiding star. It

represented the direction from which spirits travel to Earth,

symbolizing immortality.

“Almira

was also a very talented artist in other ways,” says McMullen. In Morning

Star Quilts, Pulford’s 1989 survey of quilting traditions among

Native American women of the Northern Plains, she tells of a letter

she got from Jackson that described a single month’s output: a baby

quilt, two boy’s dance outfits, two girl’s dresses, a ceremonial

headdress and a resoled pair of moccasins. “Almira was also well

known for other traditional skills,” McMullen says. “Florence was

especially intrigued by her methods for drying deer and antelope and

vegetables for winter storage.”

“Almira

was also a very talented artist in other ways,” says McMullen. In Morning

Star Quilts, Pulford’s 1989 survey of quilting traditions among

Native American women of the Northern Plains, she tells of a letter

she got from Jackson that described a single month’s output: a baby

quilt, two boy’s dance outfits, two girl’s dresses, a ceremonial

headdress and a resoled pair of moccasins. “Almira was also well

known for other traditional skills,” McMullen says. “Florence was

especially intrigued by her methods for drying deer and antelope and

vegetables for winter storage.”

Some Taíno women became notable cacique (tribal

chiefs). Such was the case of Yuisa (Luisa), a cacica in the region near

Loíza, which was later named after her. The Spanish soldiers arrived to the island without

women, which contributed to many of them marrying the native Taíno

women.

Some Taíno women became notable cacique (tribal

chiefs). Such was the case of Yuisa (Luisa), a cacica in the region near

Loíza, which was later named after her. The Spanish soldiers arrived to the island without

women, which contributed to many of them marrying the native Taíno

women. On March 22, 1873, slavery was

"abolished" in Puerto Rico, but with one significant caveat.

The slaves were not emancipated - they had to ''buy'' their own freedom,

at whatever price was set by their previous owners. Puerto Rican cuisine

and culture at the time were highly influenced by that of the traditions

of the Spanish and Tainos.

On March 22, 1873, slavery was

"abolished" in Puerto Rico, but with one significant caveat.

The slaves were not emancipated - they had to ''buy'' their own freedom,

at whatever price was set by their previous owners. Puerto Rican cuisine

and culture at the time were highly influenced by that of the traditions

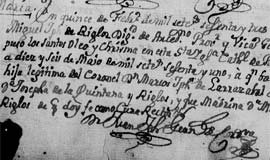

of the Spanish and Tainos. In the early 1800s, the Spanish Crown decided that

one of the ways to curb pro-independence tendencies surfacing at the

time in Puerto Rico was to allow Europeans of non-Spanish origin to

settle the island. Therefore, the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 was

printed in three languages, Spanish, English and French. Those who

immigrated to Puerto Rico were given free land and a "Letter of

Domicile" with the condition that they swore loyalty to the Spanish

Crown and allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church. After residing in the

island for five years the settlers were granted a "Letter of

Naturalization" which made them Spanish subjects.

In the early 1800s, the Spanish Crown decided that

one of the ways to curb pro-independence tendencies surfacing at the

time in Puerto Rico was to allow Europeans of non-Spanish origin to

settle the island. Therefore, the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 was

printed in three languages, Spanish, English and French. Those who

immigrated to Puerto Rico were given free land and a "Letter of

Domicile" with the condition that they swore loyalty to the Spanish

Crown and allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church. After residing in the

island for five years the settlers were granted a "Letter of

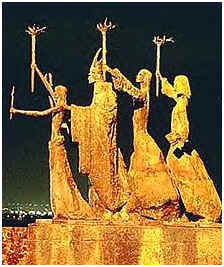

Naturalization" which made them Spanish subjects. In 1868, many Puerto Rican women participated in

the uprising known as ''El Grito de Lares'' Among the notable women who

indirectly or directly participated in the revolt and who became part of

Puerto Rican legend and lore were Lola

Rodríguez de Tio and Mariana

Bracetti. Lola Rodríguez de Tio believed in equal rights for women,

the abolition of slavery and actively participated in the Puerto Rican

Independence Movement. She wrote the lyrics to La Borinqueña, Puerto

Rico's national anthem. Mariana Bracetti, also known as ''Brazo de Oro''

(Golden Arm), was the sister-in-law of revolution leader Manuel Rojas

and actively participated in the revolt.

In 1868, many Puerto Rican women participated in

the uprising known as ''El Grito de Lares'' Among the notable women who

indirectly or directly participated in the revolt and who became part of

Puerto Rican legend and lore were Lola

Rodríguez de Tio and Mariana

Bracetti. Lola Rodríguez de Tio believed in equal rights for women,

the abolition of slavery and actively participated in the Puerto Rican

Independence Movement. She wrote the lyrics to La Borinqueña, Puerto

Rico's national anthem. Mariana Bracetti, also known as ''Brazo de Oro''

(Golden Arm), was the sister-in-law of revolution leader Manuel Rojas

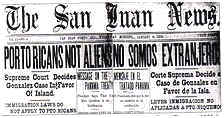

and actively participated in the revolt.  Cover of

''The San Juan News'' announcing the decision on ''Gonzales v.

Williams'' in which Puerto Ricans were not declared to be alien

immigrants when traveling to the United States. The case was argued in

court by Isabel González , a

Puerto Rican woman.

Cover of

''The San Juan News'' announcing the decision on ''Gonzales v.

Williams'' in which Puerto Ricans were not declared to be alien

immigrants when traveling to the United States. The case was argued in

court by Isabel González , a

Puerto Rican woman. In 1944, the U.S. Army sent recruiters to the

island to recruit no more than 200 women for the Women's Army Corps (WAC).

Over 1,000 applications were received for the unit which was to be

composed of only 200 women. The Puerto Rican WAC unit, Company 6, 2nd

Battalion, 21st Regiment of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, a

segregated Hispanic unit, was assigned to the Port of Embarkation of New

York City, after their basic training at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. They

were assigned to work in military offices which planned the shipment of

troops around the world. Among them was PFC Carmen

García Rosado, who in 2006, authored and published a book titled

"LAS WACS-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Segunda Guerra

Mundial" (The WACs-The participation of the Puerto Rican women in

the Second World War), the first book to document the experiences of the

first 200 Puerto Rican women who participated in said conflict.

In 1944, the U.S. Army sent recruiters to the

island to recruit no more than 200 women for the Women's Army Corps (WAC).

Over 1,000 applications were received for the unit which was to be

composed of only 200 women. The Puerto Rican WAC unit, Company 6, 2nd

Battalion, 21st Regiment of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, a

segregated Hispanic unit, was assigned to the Port of Embarkation of New

York City, after their basic training at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. They

were assigned to work in military offices which planned the shipment of

troops around the world. Among them was PFC Carmen

García Rosado, who in 2006, authored and published a book titled

"LAS WACS-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Segunda Guerra

Mundial" (The WACs-The participation of the Puerto Rican women in

the Second World War), the first book to document the experiences of the

first 200 Puerto Rican women who participated in said conflict. The arrest

of Carmen María Pérez Roque, Olga Viscal Garriga, and Ruth Mary

Reynolds; three women involved with the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party

who were arrested because of violations to the Puerto Rico Gag Law. The

law was later repealed as it was considered unconstitutional.

The arrest

of Carmen María Pérez Roque, Olga Viscal Garriga, and Ruth Mary

Reynolds; three women involved with the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party

who were arrested because of violations to the Puerto Rico Gag Law. The

law was later repealed as it was considered unconstitutional.