|

NEWSPAPER TREE

Monday,

December 9, 2013

Blowout

at UT El Paso

View from Parnassus—forty years in the vineyards of the muses

By

Felipe de Ortego y Gasca

Philip.Ortego@WNMU.EDU

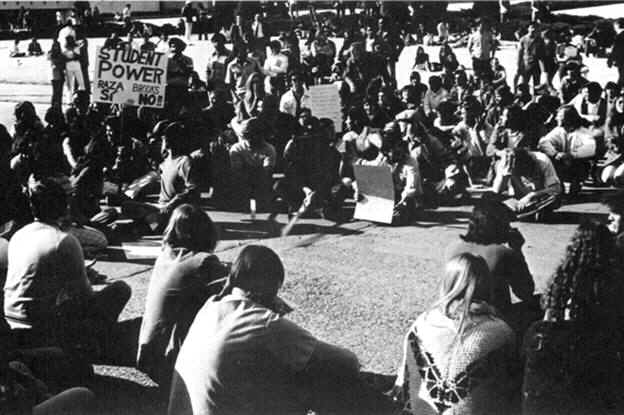

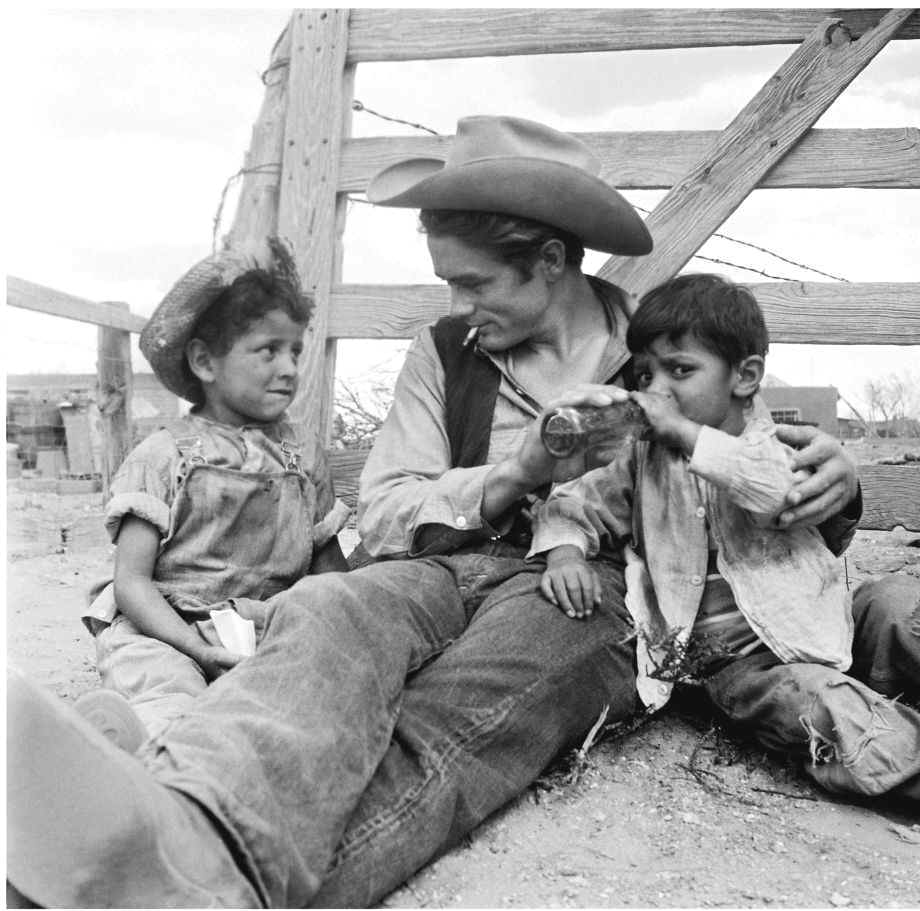

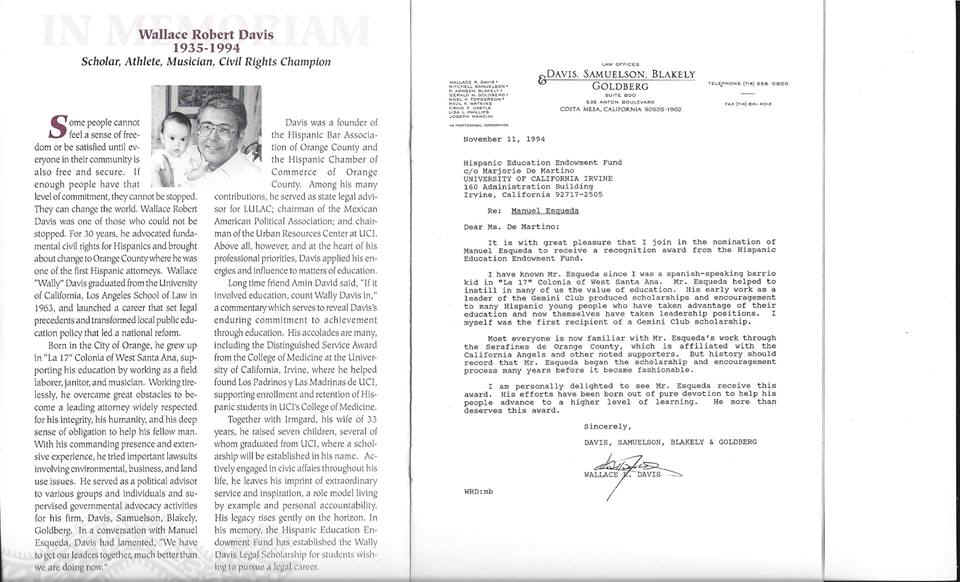

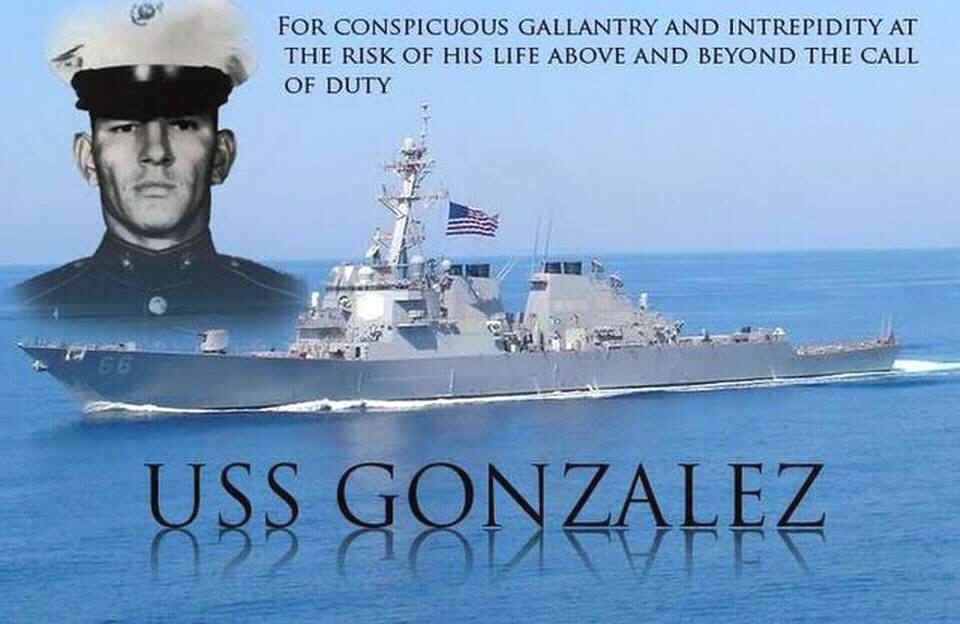

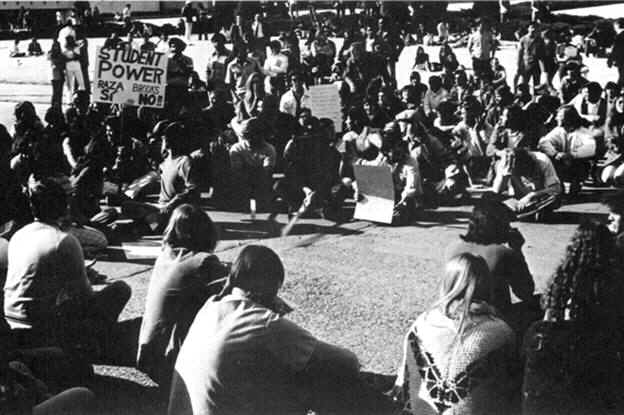

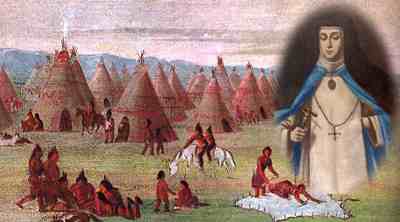

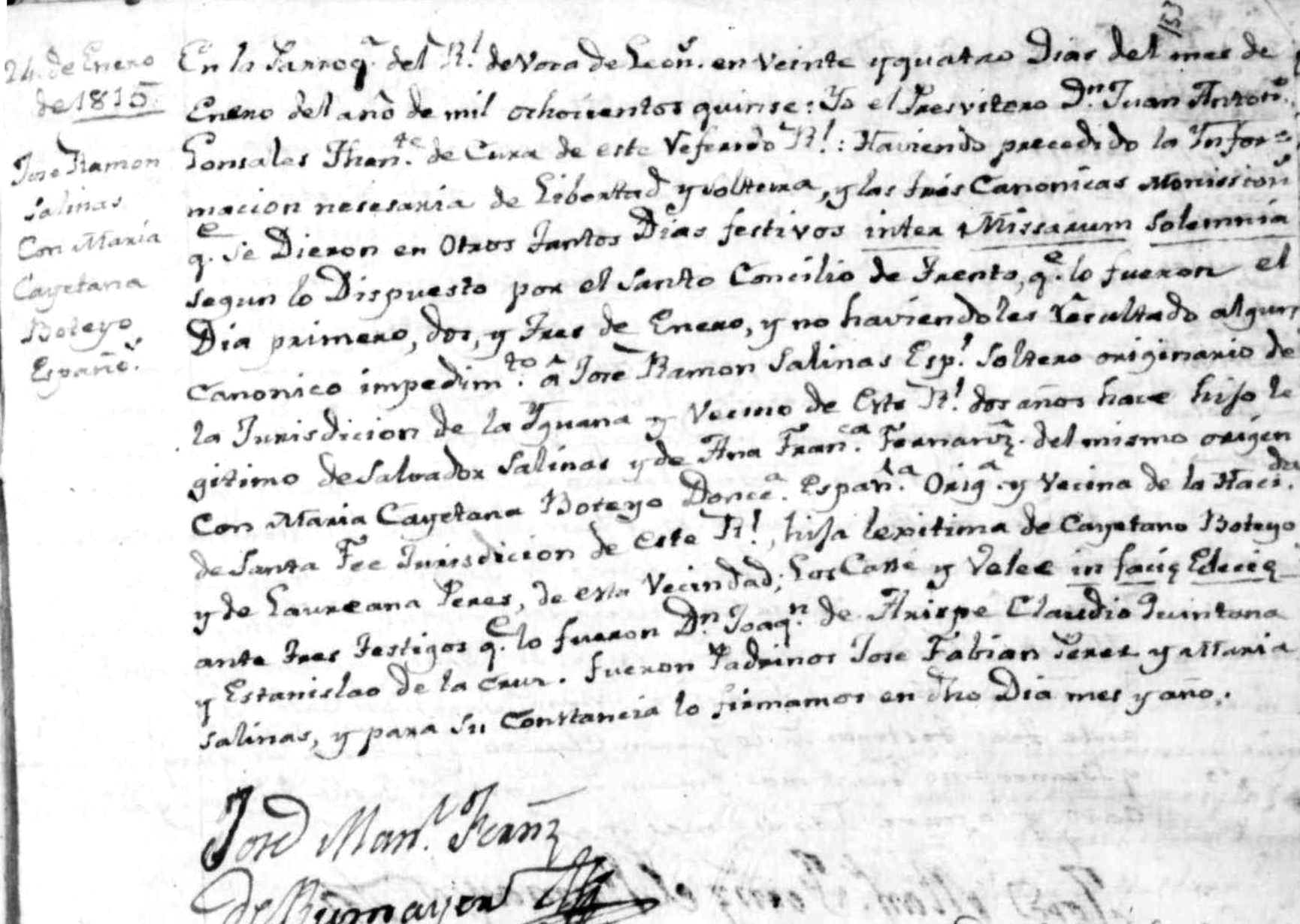

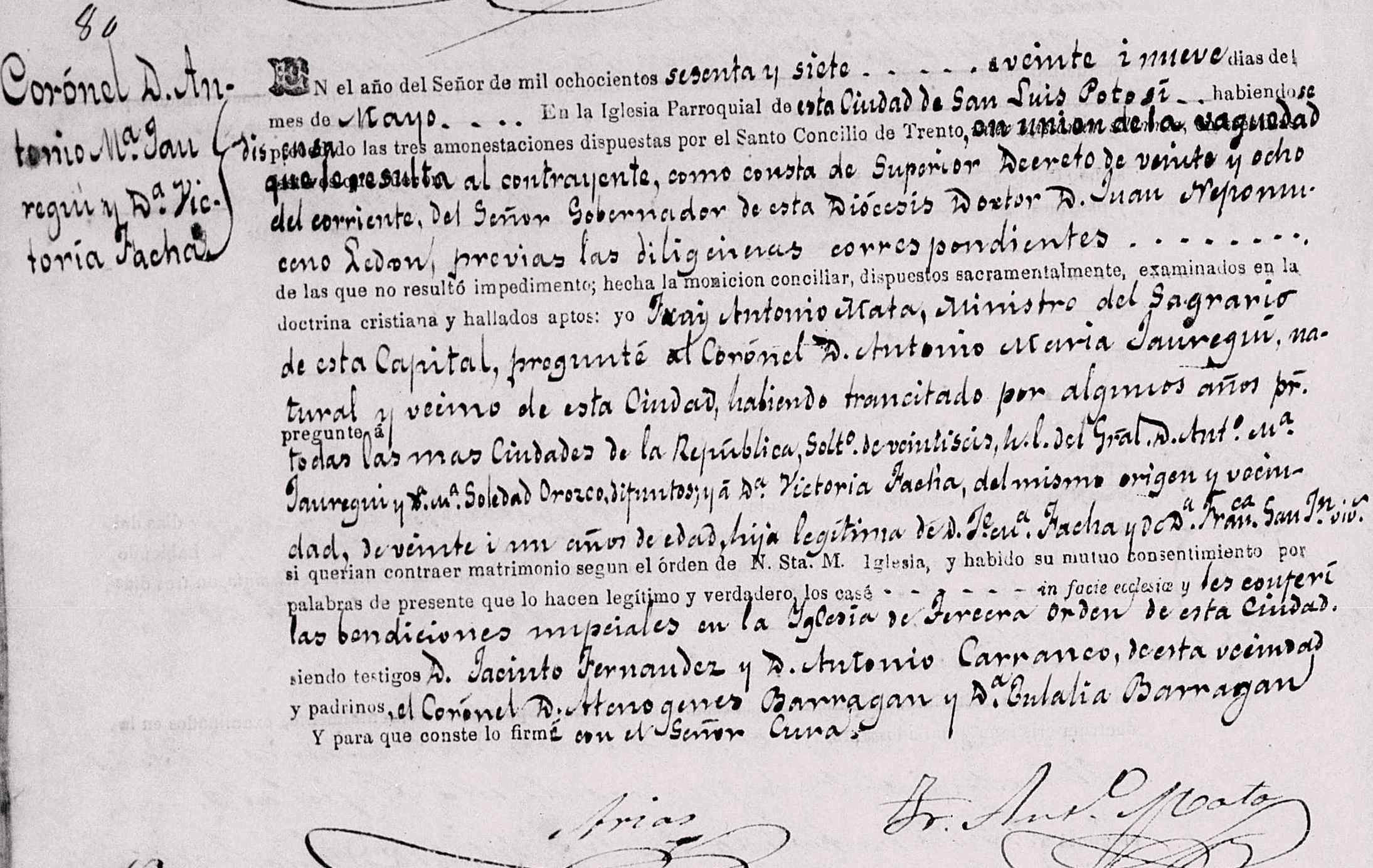

Chicano

students at UTEP stage a protest and takeover of the administration

building in 1971.

(Courtesy of The Flowsheet/University of Texas at El Paso)

Hard

to believe that 43 years ago (1970) I arrived on the campus of the

University of Texas at El Paso as founding director of the Chicano

Studies program. That happened because of Dr. Ray Small, who was then

Dean of Arts and Sciences, a mentor and friend of mine, and the Chicano

students of MEChA who took a chance on me.

That

spring I was finishing up my dissertation in English at the University

of New Mexico (UNM) in Albuquerque, on leave from New Mexico State

University in Las Cruces where I had been a member of the English

Department from 1964 to 1970. During the summer of 1969 and the academic

year 1969-1970, I was a teaching fellow in the English Department at UNM.

At

this point I should mention that in 1964, I went to Las Cruces from El

Paso where I had been the French teacher at Jefferson High School—la

Jeff. Fifty years ago, securing a position as a mejicano to teach

English in the El Paso public schools was nigh impossible. Most people

thought we spoke a corrupt version of Spanish and an equally corrupt

version of English alternating between Spanish and English referred to

as Spanglish and/or Tex-Mex.

As

a throw-away line, Hibbard Polk, assistant superintendent of the El Paso

Independent School District, asked if I could teach French. Not

expecting my response, I said, “Sure,” and explained that I had

learned French at the University of Pittsburgh where I had studied from

1948 to 1952 on the G.I. Bill. Moreover, I added, I had lived in France

from 1955 to 1958 where I had sharpened my fluency in the language. Much

to the delight of Maria Esman (Barker) I was hired. Maria was then

coordinator of foreign language instruction for the school district.

In

February of 1970, Ray Small inquired if I’d be interested in applying

for a teaching position in English with additional duties in organizing

a Chicano Studies program. Loathe as I was to leave New Mexico State

University after six years there, I said “yes,” particularly after

working with the Chicano Studies program at the University of New Mexico

during the 1969-70 academic year under the directorship of Louis

Bransford, founding director of Chicano Studies there.

It

was Louis Bransford, after all, who had asked me in August of 1969 to

organize a Chicano literature course for the Chicano Studies program,

which I did.

It

turned out that was the first course in Chicano literature in the

country—or so I have believed. Switching from a dissertation on

Chaucer to one in Chicano literature, my dissertation on “Backgrounds

of Mexican American Literature” was the first study in the field. I

was also the first mejicano to earn the Ph.D. in English at UNM. I

became cognizant of all this much later.

In

April of 1970, Ray Small informed me I was a finalist for the position

he had described, and invited me to UT El Paso for an interview. What an

interview that was! The faculty of the English department greeted me

luke-warmly, though I knew most of them. I was not prepared for the

grueling interview by the MEChA students. Mistakenly—or perhaps

pompously—I assumed that my growing reputation as a writer and scholar

in Chicano literature would carry the day for me.

I

was not only publishing well on the English and American canon of

writers (Chaucer, Shakespeare, Melville, Steinbeck, and other literary

luminaries), but also publishing well in Chicano literature and public

affairs.

My

piece on “Montezuma’s Children” was published as a cover story in The

Center Magazine of the John Maynard Hutchins Center for the Study

of Democratic Institutions and was entered into the Congressional record

by Senator Ralph Yarborough who recommended it for a Pulitzer. The piece

received a John Maynard Hutchins Award for distinguished journalism.

My

piece on “Schools for Mexican Americans” was published in the Saturday

Review. I was heralded as a Quinto Sol writer and author of numerous

short stories like “The Coming of Zamora.” In 1967, I was recipient

of the NEA-Readers Digest Foundation Award for fiction. In March of

1970, the Center for Applied Linguistics in Washington, D.C. had

published my monograph on “The Linguistic Imperative in Teaching

English to Speakers of Other Languages.” Other pieces of mine had

appeared in The Nation magazine. I was feeling secure as an

emerging scholar and writer.

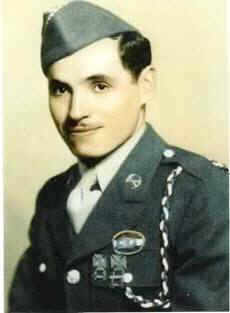

My

interview with the MEChA students was like my interrogations of

Strategic Air Command pilots

at the Air Force Survival School in the isolated high desert of Reno,

Nevada, during my ten years with the Air Force.

The

MEChA students were determined to peel away any layers of inauthenticity

in their search for the real Felipe Ortego. Having been a World War II

Marine in the Pacific, I was not intimidated by the students. In fact,

my admiration for them grew larger as they pressed on with the

interview.

They

got to the ideological nub of my commitment to the Chicano Movement.

Satisfied, they settled on me. To this day, I don’t know who the other

finalists were. But the confidence of the MEChA students in choosing me

to be founding director of Chicano Studies at UT El Paso changed my

life.

I

settled in as Founding Director of Chicano Studies at UT El Paso on

August 15, 1970, and began immediately on the proposal to the UT Board

of Regents and the Texas Commission on Higher Education to establish the

Chicano Studies program at UTEP. Helping me were MEChA students and

Mario and Richard Garcia, both of whom had finished their graduate work

at UTEP and bound for Ph.D.’s elsewhere.

With

my appointment in the English Department and that of Santiago Rodriguez

in social work, the Chicano faculty at UT El Paso doubled. On board

already were Norma Hernandez in education and Jesus Provencio in

mathematics. There were other Hispanic faculty on campus who were not

Chicanos, that is, Mexican Americans.

Of

the Chicanos, we were four in number, not counting Pete Duarte who was a

graduate student in sociology. Important to note: it only took three

Russians to foment the Bolshevik Revolution. The Chicano Studies program

was housed in Graham Hall, second floor. My appointment was jointly in

English and Chicano Studies.

I’m

loathe to recount a humorous incident that occurred that fall when I

went to the registrar’s office to pick up rosters for my classes.

Dressed in the mufti of campesinos, no sooner had I entered the

registrar’s office when pointing at me the registrar herself bellowed

that the wastebaskets in the various offices had to be emptied. Non-plussed

I explained that I was professor Ortego coming in to pick up the rosters

for my classes, whereupon the registrar bellowed: “You’re a

professor?” Adding: “What’s your name?” “Ortego,” I said.

“Ortega,” she said. “No, Ortego,” I repeated emphatically.

She

rifled through some papers and handed me the rosters to my classes. I

nodded, grabbed the papers and sauntered nonchalantly out of the

building without closing the door. Thereafter, however, when I went to

the registrar’s office, I made sure to wear a coat and tie.

What

I noticed most about UT El Paso 43 years ago was the presence of so many

mejicanos, all of them sweeping floors, cleaning windows, mowing lawns,

trimming trees, dusting furniture in offices, vacuuming carpets, and

serving food in the cafeteria. We were everywhere except in the

classrooms as faculty and as administrators at any level of the

university hierarchy.

Bear

in mind that in 1970, the mejicano population of El Paso was well over

70 percent, while almost half the student body at UT El Paso were

mejicanos. Those figures are dramatically higher today.

In

shaping the Chicano Studies program at UT El Paso—first in the state—our

bible was El Plan de Santa Barbara, the Chicano Studies template

forged at UC Santa Barbara in 1969 by the Chicano Coordinating Council

on Higher Education “as a manifesto for the implementation of Chicano

Studies,” not only in California, but everywhere. The most compelling

aspect of El Plan de Santa Barbara

was the role of community participation in Chicano Studies.

Uppermost

in our minds was the mantra that: A Chicano Studies program without

Chicano control is not a Chicano Studies program. At UT El Paso, we

quickly organized a Mesa Directiva (community advisory board) to

bring the Chicano community into the academic sphere.

The

most prominent members of la Mesa Directiva were Jose Piñon, a

pharmacist and Hector Bencomo, a grocer and El Paso councilman. Both

were to play key roles in the MEChA takeover of the administration

building in December of 1971.

While

the Chicano Studies proposal formally established the Chicano Studies

program at UT El Paso, the principal impetus for the formation of

Chicano Studies on campus came from the MEChA students, roiled into

action by the string of high school walkouts during 1969, among them the

student walkouts at Bowie High School and at Jefferson High School.

Chicano

activism was not exclusively a California phenomenon, though the first

Chicano Studies program in the country was established at California

State University—Los Angeles in 1968, followed by formation of the

Chicano Studies Department at California State University—Northridge

in 1969. In 1970 the first Chicano Studies program in Texas was

established at the University of Texas at El Paso, third in the nation,

although UT Austin has contested that claim. Celos! Puros celos!

There

were many considerations to take into account in getting Chicano Studies

up and running at UT El Paso, first among them, an academic structure

consonant with the philosophy and objectives of Chicano Studies. We all

knew what was needed and where we wanted to go. The question was: How to

get there? And, of course, how to decide?

The

first steps were obvious. We organized a Chicano caucus of students,

faculty, and community supporters. The proposal for the Chicano Studies

program came out of this caucus. Needless to say there were hurdles in

the deliberations of the caucus, deliberations which gave credence to

the proposition that when you get three Chicanos to deliberate you get

four opinions. But I jest!

Focused

and single-minded, and thanks to students of MEChA, the caucus achieved

not just consensus but unanimity. By November, we received word that the

Chicano Studies proposal had been approved by the University of Texas

Board of Regents and the Higher Education Coordinating Board of Texas.

Anticipating

that approval, we hired Ana Osante—may she rest in peace—as the

Chicano Studies secretary who came to embody the spirit of Chicano

Studies. With so much preliminary work to conduct, we hired student

workers as well—two of whom were Patricia Roybal (now a New Mexico

state representative) and Hilda Parra.

There

were administrators and faculty members who wanted us to succeed; and

there were those who wanted to see us fail, that is, those who regarded

Chicano Studies as a divisive academic wedge. In part, that perspective

nudged us toward crafting Chicano Studies as an interdisciplinary

program and as a strategy for Chicano staffing by the departments: we

would have courses and a cudgel in getting Chicano faculty into the

departments.

Increasing

the presence of Chicano faculty on campus would prove to be our

donnybrook. The stumbling block there was garnering faculty support in

the departments to hire Chicano faculty. In this regard, our strongest

faculty supporters then were John Haddox, professor of philosophy,

Melvin Strauss, professor of political science, and Ray Small, dean of

arts and sciences.

There

were others, of course, not many, but others. I always thought President

Smiley was in our camp but caught in a web of disdain and malice wrought

by the powers in the UT system who saw us as “Meskins,” pretty much

the way the Texas Rangers and Walter Prescott Webb saw us. In the end,

Joe Smiley and I were collateral victims in the ideological struggle for

Chicano representation at UT El Paso.

Many

of us in the Chicano caucus thought that the interdisciplinary approach

was preferable since it seemed to be a way of increasing our numbers

throughout the academic departments rather than clustering them

ghetto-like in one department. At Western New Mexico University, we have

a Department of Chicana/Chicano and Hemispheric Studies with affiliate

faculty in the various academic departments of the university, a hybrid

version of a departmental and interdisciplinary structure which seems to

be working well for us. We have the autonomy of a department while at

the same time influence in the departments via Hispanic/Latino faculty.

No

matter the structure, the interdisciplinary program of Chicano Studies

at UT El Paso has survived 43 years. That’s a testament to its

foundation and its stewardship with Dr. Dennis Bixler-Marquez at its

helm. But its history has not been without travail.

In

recruiting Chicano professors for the various disciplines, we were met

with departmental disdain and intransigence engendered by institutional

racism. No departments were taking us seriously. That’s what ignited

the MEChA takeover of the Administration Building and holding the

president hostage on that December day of 1971.

We

were all frustrated; the students moreso. Our efforts at galvanizing the

mejicano community to support us were met with consejos to tone

down the rhetoric, to slow down, we were going too fast, expecting too

much, too soon.

In

the spring of that year when Tony Bonilla, Texas director of LULAC and I

and a contingent of mejicanos (including students) from El Paso met with

Texas Governor Preston Smith, beseeching him to appoint mejicanos to

Texas universities’ boards of regents, he had his sergeant-at-arms

throw us out of his office, admonishing us that as governor, he could

not favor one group over another. That was the climate in Texas at that

time. The favored group were Anglos.

That

fatiric morning of the takeover, I was caught by surprise. Not that the

students didn’t trust me; they were protecting me, but I perished

anyway. After a morning of wrangling with President Smiley, we were no

further ahead than when we started. None of us could persuade the

president to consider our “demands”—perhaps “non-negotiable

demands” was a poor choice of words.

Then

silently, as the clock moved toward noon, the MEChA students ushered the

secretaries out of

the

office and locked the doors. Phones were disabled. Joe Smiley grew

nervous. The room crackled with the electricity of uncertainty. I felt

like an actor in a play with an unfamiliar script, improvising the next

scene, ad-libbing the lines.

Outside,

as if anticipating the takeover, Chicano students began to flock around

the adminis-tration building. Newspaper estimates described the throng

as 3,500 strong, but Agapito Mendoza, who went on to become vice provost

at the University of Missouri at Kansas City, asserts that 5,000 Chicano

students encircled the administration building, keeping out the police

and other authorities, chanting paeans of liberation.

Other

students were letting the air out of the tires of police cars and buses,

alert to police snipers on the roofs of nearby buildings, alert to the

aggregation of sheriffs’ posses and military troops from nearby Fort

Bliss. On that autumn day of December 1971, Chicano students at UT El

Paso had stormed their Bastille and were at one with other student

liberators around the globe.

I

was not the leader of the group, but as its most elder I wheedled, I

pleaded, I sought to get Joseph Smiley to see the justice of our cause.

Nothing seemed to work but, finally the impasse broke and we reached a

settlement with the president.

Via

his office, he would support stronger recruitment of Chicano faculty,

more departmental collegiality with Chicano Studies, a stronger

institutional affirmative action plan to improve opportunities for

Chicano staff within the university infrastructure. We were victorious—but

at what cost? The students were rounded up and carted off to jail.

Thanks to the efforts of Hector Bencomo, Jose Piñon, Jesus Ochoa, Tati

Santiestaban, and Paul Moreno, no one was charged with any crime—branded,

yes, but not charged. The university would not press charges against us,

though the event had serious criminal consequences, including kidnapping—a

felony.

I

was regarded as the instigator—my contract was not renewed for the

1972-73 academic year. Pero como dice el dicho: no hay mal que por

bien no venga—even an ill wind blows some good.

I

moved to Denver to be assistant to the president at Metro State College

where I met Dan Valdes and became one of the founders of La Luz

magazine, the first national Hispanic public affairs magazine in

English.

In

1973, I went off to Columbia University for post-doctoral studies in

management and planning for higher education, which helped me in 1974 as

one of the founders of the Hispanic University of America, the first

major effort to establish a stand-alone university for American Hispanos

by American Hispanos. I was named vice-chancellor for academic

development.

Joe

Smiley was forced into retirement for giving in to the demands of the

MEChA students. But the acrimony that event engendered from the Anglo

professoriate at UTEP, the Anglo students on campus, and the Anglo

community of El Paso, persisted for many years after.

Some

professors stopped talking to me; others became hostile; some branded me

as a “commu-nist.” Some of that acrimony persists to this day,

fueled by the fiery vestiges of “the Black Legend”—the stereotypes

that have plagued Spaniards and their progeny everywhere since the

defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

The

takeover was not in vain. The MEChA students had served notice on the

university—nay, to Texas—that the “good ol’ boy” way of doing

business with mejicanos was headed for the scrap-heap of history. We

made great strides the following semester.

By

the time I left UT El Paso in May of 1972, the Chicano faculty included

Tomas Arciniega in education, Rudolfo de la Garza in political science,

Donald Castro in English, Hector Serrano in drama, Rudy Gomez in

history, and Karen Ramirez in linguistics. There were others. In

retrospect, nos despedimos (we left) with heads held high. Pero

la lucha continuó y contínua! But the struggle continued and

still continues!

Years

later, Joe Olvera wrote to me saying: “Thank you, Dr. Ortego. I’ll

never forget how you stood with us when we took over the Administration

Building at UTEP in 1971 and held the President hostage. Your courage

under fire was admirable. You placed your career on the line and never

flinched. But of course you had been a Marine during World War II. No

wonder your bravery was so uncompromising.”

*******************

A

note on the title: In Greek mythology, Parnassus was the home of the

muses.

A version of this article originally appeared in “Pluma Fronteriza”

on October 20, 2010.

********************

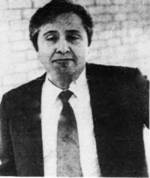

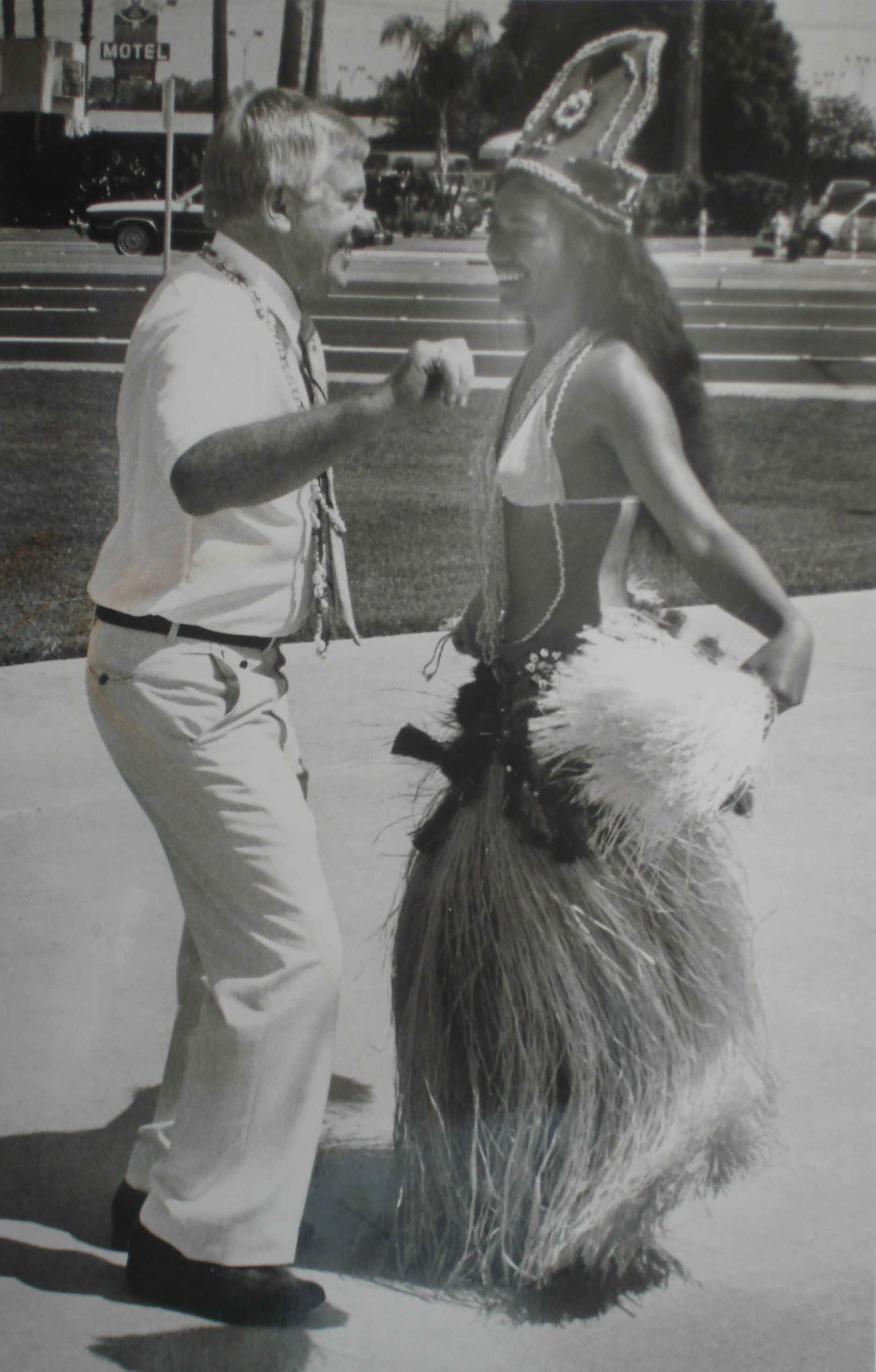

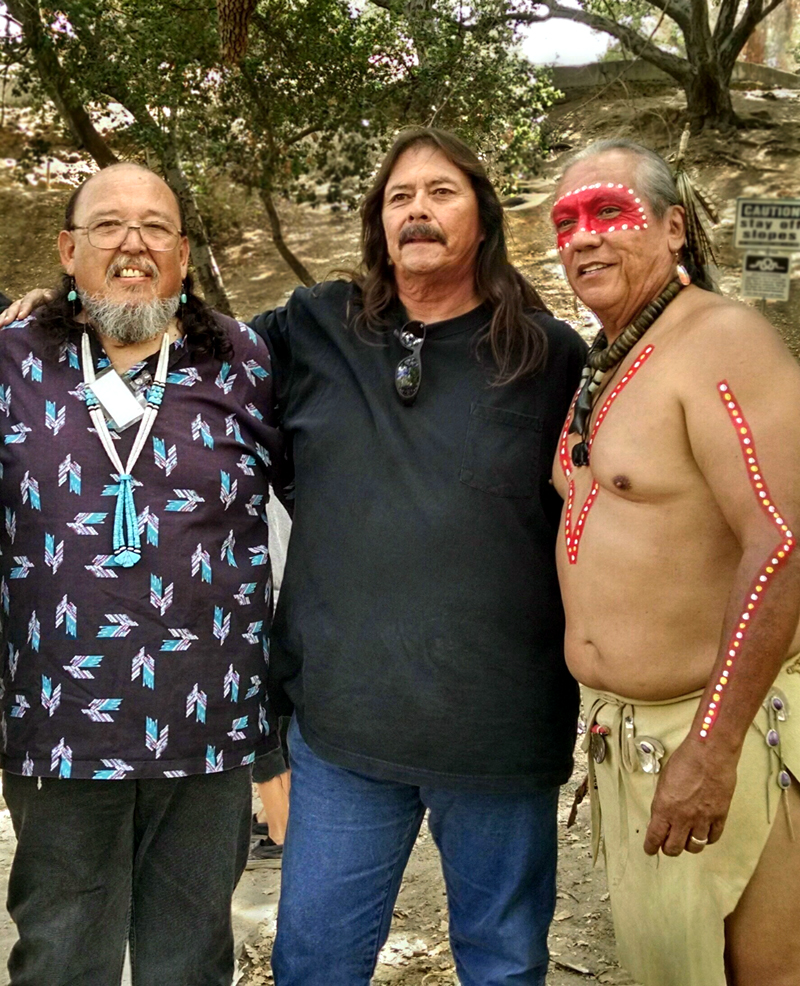

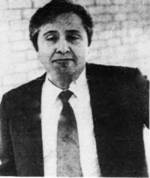

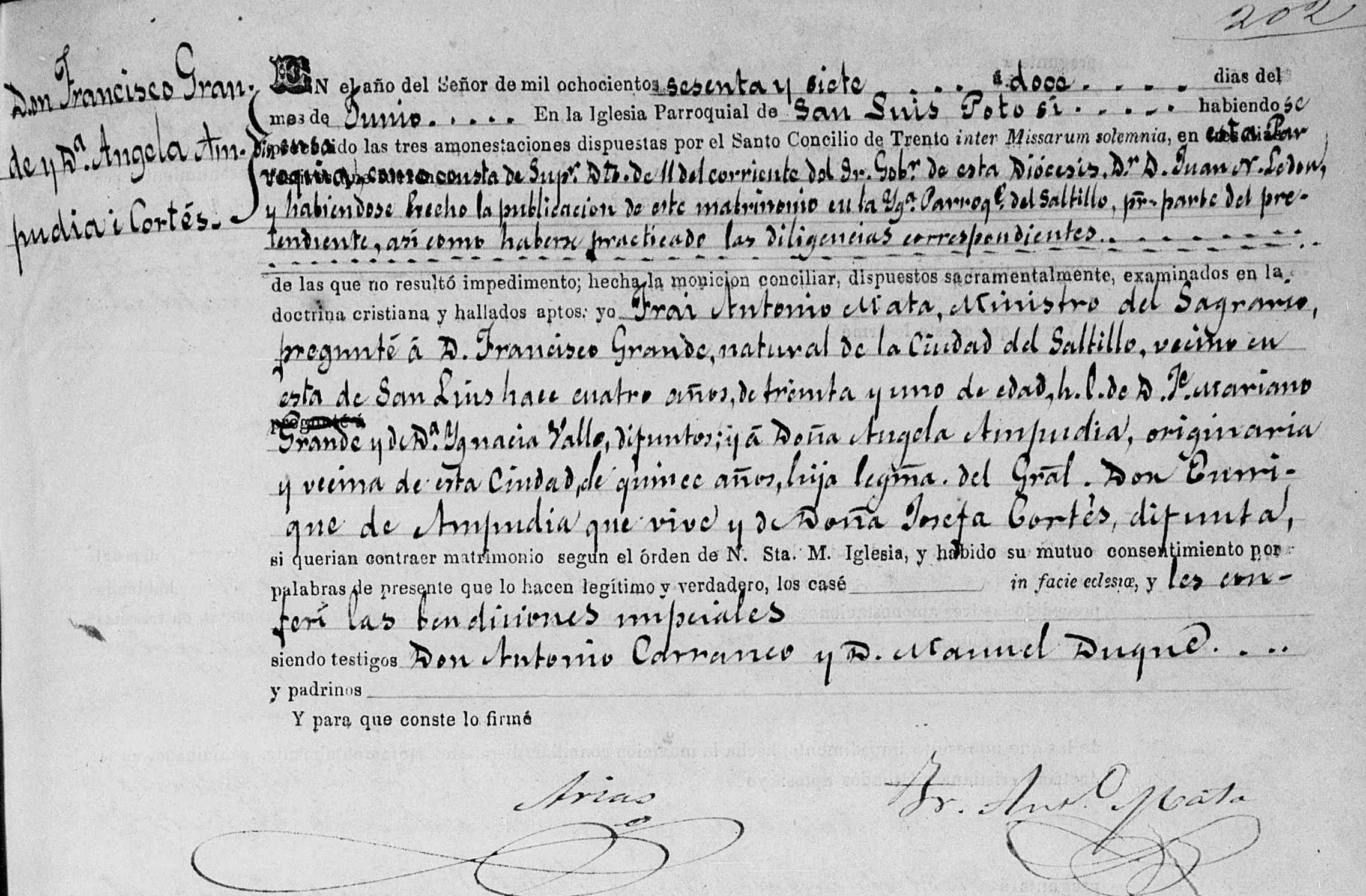

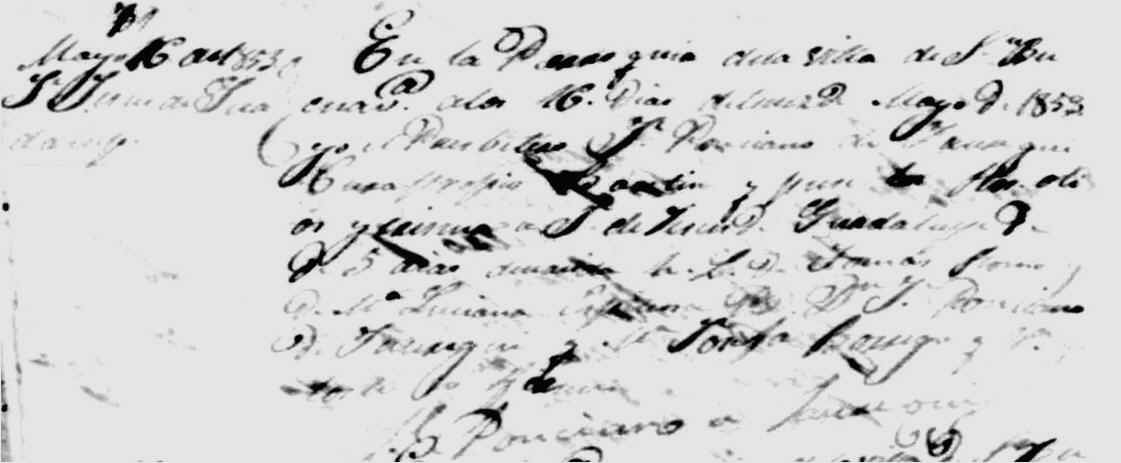

Welcome

to the UTEP Encyclopedia: One hundred years of UTEP history in one place

Philip Ortego, 1971 Philip Ortego, 1971

Prospector, Newspaperarchive.com

Philip

Ortego, Director of Chicano studies and Assistant Professor of English

at UTEP, denounces the school as a “racist

institution” for not supporting Chicano Studies with

institutional resources.

|

Inarritu's best director win makes it two years in a row that the honor has gone to a Mexican filmmaker. His friend, Alfonso

Cuaron, won the Oscar last year for "Gravity", the 3-D space thriller starring Sandra Bullock and George

Clooney.

Inarritu's best director win makes it two years in a row that the honor has gone to a Mexican filmmaker. His friend, Alfonso

Cuaron, won the Oscar last year for "Gravity", the 3-D space thriller starring Sandra Bullock and George

Clooney.

This year the keynote speakers were John Valadez producer of the Longoria Affair and Paul Eno, Director of Information Technology of General Motors.

This year the keynote speakers were John Valadez producer of the Longoria Affair and Paul Eno, Director of Information Technology of General Motors.

If

the statistics do not exist, the need for change does not exist. Like in

the case of urban renewal, the objective is growth that allows larger

administrative salaries, larger staffs, and bigger buildings that are

then named after donors – again they are messing with memory.

If

the statistics do not exist, the need for change does not exist. Like in

the case of urban renewal, the objective is growth that allows larger

administrative salaries, larger staffs, and bigger buildings that are

then named after donors – again they are messing with memory.

February,

8th, at the Annual Grammy Awards, Legend “Flaco Jimenez” was

presented a Lifetime Grammy Award. Attached is a brief video

tribute to the legendary Artist of Tejano American Tex-Mex culture in

music and more. Truly overdue I'm sure.

February,

8th, at the Annual Grammy Awards, Legend “Flaco Jimenez” was

presented a Lifetime Grammy Award. Attached is a brief video

tribute to the legendary Artist of Tejano American Tex-Mex culture in

music and more. Truly overdue I'm sure.

residents

of this traditional Chavez Ravine community. Unfortunately, this form of

social gentrification and profit-driven urban removal that dislocated

this closely-knit neighborhood over fifty years ago is still alive and

stronger than ever. The present economic power of developers and the

drive to profitably exploit vulnerable communities within the central

city and drastically change their ethnic, class and cultural composition

continues to steadily displace the long-time residents of many

neighborhoods. Chavez

Ravine home owners stage a sit-in outside the office of Mayor Bowron to

protest their evictions.

residents

of this traditional Chavez Ravine community. Unfortunately, this form of

social gentrification and profit-driven urban removal that dislocated

this closely-knit neighborhood over fifty years ago is still alive and

stronger than ever. The present economic power of developers and the

drive to profitably exploit vulnerable communities within the central

city and drastically change their ethnic, class and cultural composition

continues to steadily displace the long-time residents of many

neighborhoods. Chavez

Ravine home owners stage a sit-in outside the office of Mayor Bowron to

protest their evictions. was

trying to hustle up a different site in Brooklyn for his new Dodger’s

baseball stadium and had used the tactic of threatening to move his team

to another city as leverage to strong-arm New York politicians into

agreeing to his plan. This request by O’Malley for a new stadium site

was firmly rejected by New York officials who felt that he was trying to

take advantage of the city’s taxpayers. The next characters to enter

this political mix were LA City Council member Roz Wyman and other

politicians and developers who saw the potential benefits of a financial

deal that would bring the Dodgers to LA.

was

trying to hustle up a different site in Brooklyn for his new Dodger’s

baseball stadium and had used the tactic of threatening to move his team

to another city as leverage to strong-arm New York politicians into

agreeing to his plan. This request by O’Malley for a new stadium site

was firmly rejected by New York officials who felt that he was trying to

take advantage of the city’s taxpayers. The next characters to enter

this political mix were LA City Council member Roz Wyman and other

politicians and developers who saw the potential benefits of a financial

deal that would bring the Dodgers to LA. and

developers with the Dodger organization left a trail of unethical

political maneuvering, pay-off money and broken families for those

driven out of their homes and community by this wealthy and powerful

alliance. During the decade of the 1950’s many of the evicted

residents from Chavez Ravine were dispersed like refugees into other

neighborhoods such as Echo Park, Riverside Drive and across the river

into Lincoln Heights.

and

developers with the Dodger organization left a trail of unethical

political maneuvering, pay-off money and broken families for those

driven out of their homes and community by this wealthy and powerful

alliance. During the decade of the 1950’s many of the evicted

residents from Chavez Ravine were dispersed like refugees into other

neighborhoods such as Echo Park, Riverside Drive and across the river

into Lincoln Heights. In

1960, the woodsy hills of Chavez Ravine were bulldozed by the city to

build Dodger Stadium for O’Malley.

In

1960, the woodsy hills of Chavez Ravine were bulldozed by the city to

build Dodger Stadium for O’Malley.  The

victims of gentrification do not simply disappear from sight. There is

now a homeless camp along the Arroyo riverbank made up of ex-Highland

Park residents who have been evicted due to the rapid wave of

gentrification occurring within the north end of Highland Park. There

are many other homeless camps now sprouting up along the banks of the

river and in areas of Elysian and Griffith Parks. The question for these

new homeless people of where to live is a growing problem not only for

them, but also for many others in the same situation. Forcing people out

of their homes and neighborhoods and disrupting their families and

children’s lives is not a logical solution, but merely contributes to

broader social and financial problems for those evicted and for our

society while simultaneously creating an aggressive new system of

economic and ethnic segregation within the city. Organized

resistance to gentrification is growing such as in Boyle Heights.

The

victims of gentrification do not simply disappear from sight. There is

now a homeless camp along the Arroyo riverbank made up of ex-Highland

Park residents who have been evicted due to the rapid wave of

gentrification occurring within the north end of Highland Park. There

are many other homeless camps now sprouting up along the banks of the

river and in areas of Elysian and Griffith Parks. The question for these

new homeless people of where to live is a growing problem not only for

them, but also for many others in the same situation. Forcing people out

of their homes and neighborhoods and disrupting their families and

children’s lives is not a logical solution, but merely contributes to

broader social and financial problems for those evicted and for our

society while simultaneously creating an aggressive new system of

economic and ethnic segregation within the city. Organized

resistance to gentrification is growing such as in Boyle Heights.

Truly

she is a Daughter of the Dons — beautiful, vivacious, talented

Lucretia del Valle, scion of an ancient Spanish-California family,

whose picture is to circle the globe as that of a typical California

girl, so declared by her compatriots in southern California. That the

choice is an especially happy one, and that the commonwealth is to be

congratulated on the wisdom of the Southland in selecting this

particular one of many charming daughters to carry her message around

the world, is evident from even a brief survey of the facts.

Truly

she is a Daughter of the Dons — beautiful, vivacious, talented

Lucretia del Valle, scion of an ancient Spanish-California family,

whose picture is to circle the globe as that of a typical California

girl, so declared by her compatriots in southern California. That the

choice is an especially happy one, and that the commonwealth is to be

congratulated on the wisdom of the Southland in selecting this

particular one of many charming daughters to carry her message around

the world, is evident from even a brief survey of the facts.

http://www.scvhistory.com/gif/mugs/lucretiadelvalle.jpgA

lifesize, 70x60-inch portrait titled "The Leading Lady" by the

American impressionist painter Guy Rose depicts Lucretia in her role as

Doña Josefa Yorba. It won the gold medal at the 1915 Panama-California

Exposition in San Diego and now resides in Balboa Park's San Diego

History Center.

http://www.scvhistory.com/gif/mugs/lucretiadelvalle.jpgA

lifesize, 70x60-inch portrait titled "The Leading Lady" by the

American impressionist painter Guy Rose depicts Lucretia in her role as

Doña Josefa Yorba. It won the gold medal at the 1915 Panama-California

Exposition in San Diego and now resides in Balboa Park's San Diego

History Center.

San

Ysidro and The Tijuana River Valley (Images of America (Arcadia

Publishing)

San

Ysidro and The Tijuana River Valley (Images of America (Arcadia

Publishing)

The

railroad solidified Laredo’s lasting importance for transportation to

and from Mexico and contributed significantly to Laredo’s development.

In 1881, Laredo was connected with Corpus Christi by the Texas Mexican

Railroad and San Antonio by the International and Great Northern

Railroad. As the first Texas border city south of Eagle Pass to have a

railroad, Laredo prospered in the late 19th century, especially with the

completion, in 1887, of a railroad connecting Nuevo Laredo with Mexico

City. Laredo became a key stop in a long railroad network of

Mexican-American economic exchange.

The

railroad solidified Laredo’s lasting importance for transportation to

and from Mexico and contributed significantly to Laredo’s development.

In 1881, Laredo was connected with Corpus Christi by the Texas Mexican

Railroad and San Antonio by the International and Great Northern

Railroad. As the first Texas border city south of Eagle Pass to have a

railroad, Laredo prospered in the late 19th century, especially with the

completion, in 1887, of a railroad connecting Nuevo Laredo with Mexico

City. Laredo became a key stop in a long railroad network of

Mexican-American economic exchange. The

Alexanders, one of the most prominent Jewish families in Laredo, also

arrived at the end of the 19th century. Confederate Army veteran Sam

Alexander and his wife Rosa were German immigrants who arrived in Laredo

from Victoria in the 1890s, though it was their sons who contributed

heavily to Laredo’s growth and development. By 1896, their eldest son,

Isaac, owned I. Alexander Clothing Company with his brothers Louis and

William. Isaac, remembered long after his death as a “business genius”

by a local newspaper,

The

Alexanders, one of the most prominent Jewish families in Laredo, also

arrived at the end of the 19th century. Confederate Army veteran Sam

Alexander and his wife Rosa were German immigrants who arrived in Laredo

from Victoria in the 1890s, though it was their sons who contributed

heavily to Laredo’s growth and development. By 1896, their eldest son,

Isaac, owned I. Alexander Clothing Company with his brothers Louis and

William. Isaac, remembered long after his death as a “business genius”

by a local newspaper, Due

to the leadership of these New York-based rabbis, Laredo Jews

established a congregation, B’nai Israel (“Children of Israel”),

in 1916, with Ferdinand Wormser as president. By 1918, the Jews of

Laredo were holding weekly Shabbat services, though the style of these

services is unclear. The Laredo Timeswrites of high holiday services at

“Congregation B’nai Israel Hall” for Rosh Hashanah in1919, though

the Jews of Laredo almost certainly used rented facilities, such as the

Western Union building or a room above a drug store. By 1919, the Jews

of Laredo had formed a Ladies’ Jewish Aid Society, a cemetery

association, and a Sunday school, organized by Albert Granoff, which was

held in a Laredo public school. Due to the leadership of these New

York-based rabbis, Laredo Jews established a congregation, B’nai

Israel (“Children of Israel”), in 1916, with Ferdinand Wormser as

president. By 1918, the Jews of Laredo were holding weekly Shabbat

services, though the style of these services is unclear. The Laredo

Times writes of high holiday services at “Congregation B’nai Israel

Hall” for Rosh Hashanah in1919, though the Jews of Laredo almost

certainly used rented facilities, such as the Western Union building or

a room above a drug store. By 1919, the Jews of Laredo had formed a

Ladies’ Jewish Aid Society, a cemetery association, and a Sunday

school, organized by Albert Granoff, which was held in a Laredo public

school.

Due

to the leadership of these New York-based rabbis, Laredo Jews

established a congregation, B’nai Israel (“Children of Israel”),

in 1916, with Ferdinand Wormser as president. By 1918, the Jews of

Laredo were holding weekly Shabbat services, though the style of these

services is unclear. The Laredo Timeswrites of high holiday services at

“Congregation B’nai Israel Hall” for Rosh Hashanah in1919, though

the Jews of Laredo almost certainly used rented facilities, such as the

Western Union building or a room above a drug store. By 1919, the Jews

of Laredo had formed a Ladies’ Jewish Aid Society, a cemetery

association, and a Sunday school, organized by Albert Granoff, which was

held in a Laredo public school. Due to the leadership of these New

York-based rabbis, Laredo Jews established a congregation, B’nai

Israel (“Children of Israel”), in 1916, with Ferdinand Wormser as

president. By 1918, the Jews of Laredo were holding weekly Shabbat

services, though the style of these services is unclear. The Laredo

Times writes of high holiday services at “Congregation B’nai Israel

Hall” for Rosh Hashanah in1919, though the Jews of Laredo almost

certainly used rented facilities, such as the Western Union building or

a room above a drug store. By 1919, the Jews of Laredo had formed a

Ladies’ Jewish Aid Society, a cemetery association, and a Sunday

school, organized by Albert Granoff, which was held in a Laredo public

school. Another

example of the blending of Jewish and Mexican culture on the American

border can be seen in the family of Israel Goldberg. Goldberg, a native

of Lithuania, traveled from Europe to Tampico, arriving in Nuevo Laredo

by 1929. He eventually became a Mexican citizen and immigrated to the

United States in 1946. In 1947, Goldberg took over his brother Nathan’s

Army and Navy Surplus store. Goldberg was advised to adopt a more common

Mexican name to help his business, so Israel Goldberg became “Don Raul”

Goldberg and his store became “Casa Raul.” In 2011, the store

remained in business, run by Raul’s daughter Evelyn Selig and her two

brothers, Moses and Henry Goldberg.

Another

example of the blending of Jewish and Mexican culture on the American

border can be seen in the family of Israel Goldberg. Goldberg, a native

of Lithuania, traveled from Europe to Tampico, arriving in Nuevo Laredo

by 1929. He eventually became a Mexican citizen and immigrated to the

United States in 1946. In 1947, Goldberg took over his brother Nathan’s

Army and Navy Surplus store. Goldberg was advised to adopt a more common

Mexican name to help his business, so Israel Goldberg became “Don Raul”

Goldberg and his store became “Casa Raul.” In 2011, the store

remained in business, run by Raul’s daughter Evelyn Selig and her two

brothers, Moses and Henry Goldberg. In

1924 the congregation once again discussed the building of a synagogue

though they avoided the question of religious ritual. The group

eventually purchased a plot of land, though they had not yet made a

decision about the religious affiliation of the congregation. In a

tenuous sign of unity, the two groups collaborated for high holiday

services in the 1920s, renting the same building though holding separate

services. The Orthodox group held services first, followed by the Reform

group. However, according to Albert Granoff, the collaboration drew the

groups further apart, as the Orthodox group was intolerant of Reform

practices while the Orthodox customs were misunderstood by the Reform

congregants. One year in the late 1920s, the Reform group brought

down student rabbi Aaron Lefkowitz from Hebrew Union College in

Cincinnati and held separate services in the American Legion Hall.

Laredo’s Jewish community had split over religious lines. Despite this

conflict over religious rituals, Laredo Jews worked together in B’nai

B’rith, with members from both factions serving in leadership

positions with the local chapter.

In

1924 the congregation once again discussed the building of a synagogue

though they avoided the question of religious ritual. The group

eventually purchased a plot of land, though they had not yet made a

decision about the religious affiliation of the congregation. In a

tenuous sign of unity, the two groups collaborated for high holiday

services in the 1920s, renting the same building though holding separate

services. The Orthodox group held services first, followed by the Reform

group. However, according to Albert Granoff, the collaboration drew the

groups further apart, as the Orthodox group was intolerant of Reform

practices while the Orthodox customs were misunderstood by the Reform

congregants. One year in the late 1920s, the Reform group brought

down student rabbi Aaron Lefkowitz from Hebrew Union College in

Cincinnati and held separate services in the American Legion Hall.

Laredo’s Jewish community had split over religious lines. Despite this

conflict over religious rituals, Laredo Jews worked together in B’nai

B’rith, with members from both factions serving in leadership

positions with the local chapter.

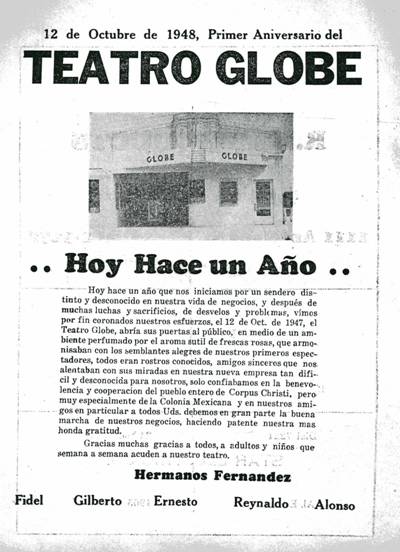

When the theater opened its doors in

1947, it introduced the Fernandez family to a new and exciting daily

adventure which consumed the time of my Grandmother Mama Lolita’s

family.

When the theater opened its doors in

1947, it introduced the Fernandez family to a new and exciting daily

adventure which consumed the time of my Grandmother Mama Lolita’s

family. idel

was in charge of selling tickets, but sometimes Ofelia Segura or cousin

Dolores Fernandez assisted.

idel

was in charge of selling tickets, but sometimes Ofelia Segura or cousin

Dolores Fernandez assisted.

One day (a long time ago—in the

pre-Internet era) I was a graduate student at the University of Michigan

at Ann Arbor chipping away at my master’s degree in social studies

education, and so one day I went to what was then called the UofM

Graduate Library which was in the middle of the campus. I had gone there

to explore what I was told might be a source of data on the demographics

of Michigan prior to 1900. One librarian told me that perhaps I might

therefore want to look at the census data contained in the volumes (i.e.

dusty old books) of census data in the attic area of the UofM Graduate

Library.

One day (a long time ago—in the

pre-Internet era) I was a graduate student at the University of Michigan

at Ann Arbor chipping away at my master’s degree in social studies

education, and so one day I went to what was then called the UofM

Graduate Library which was in the middle of the campus. I had gone there

to explore what I was told might be a source of data on the demographics

of Michigan prior to 1900. One librarian told me that perhaps I might

therefore want to look at the census data contained in the volumes (i.e.

dusty old books) of census data in the attic area of the UofM Graduate

Library.

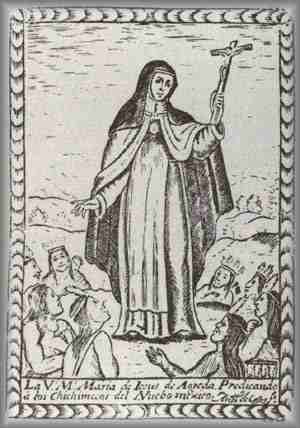

Mary

of Agreda obediently told the three priests all that concerned her

visits to the Indians of America. Since she was a child, she said, she

had been inspired to pray for the Indians in New Spain, whose souls

would be lost unless they converted to the one true Faith.

Mary

of Agreda obediently told the three priests all that concerned her

visits to the Indians of America. Since she was a child, she said, she

had been inspired to pray for the Indians in New Spain, whose souls

would be lost unless they converted to the one true Faith.

Hearing

the words of Mother Mary of Jesus, the missionary priest was much moved.

To verify the truth of her account, he asked her specific questions

about the area, if she could identify certain landmarks and describe the

other missionaries, as well as specific Indians. “She told me many

particularities of that land that even I had forgotten and she brought

them to my memory,” he noted. She also described the features and

individual traits of the missionaries and various Indians, with details

that only a person who had been in New Spain could know.

Hearing

the words of Mother Mary of Jesus, the missionary priest was much moved.

To verify the truth of her account, he asked her specific questions

about the area, if she could identify certain landmarks and describe the

other missionaries, as well as specific Indians. “She told me many

particularities of that land that even I had forgotten and she brought

them to my memory,” he noted. She also described the features and

individual traits of the missionaries and various Indians, with details

that only a person who had been in New Spain could know.

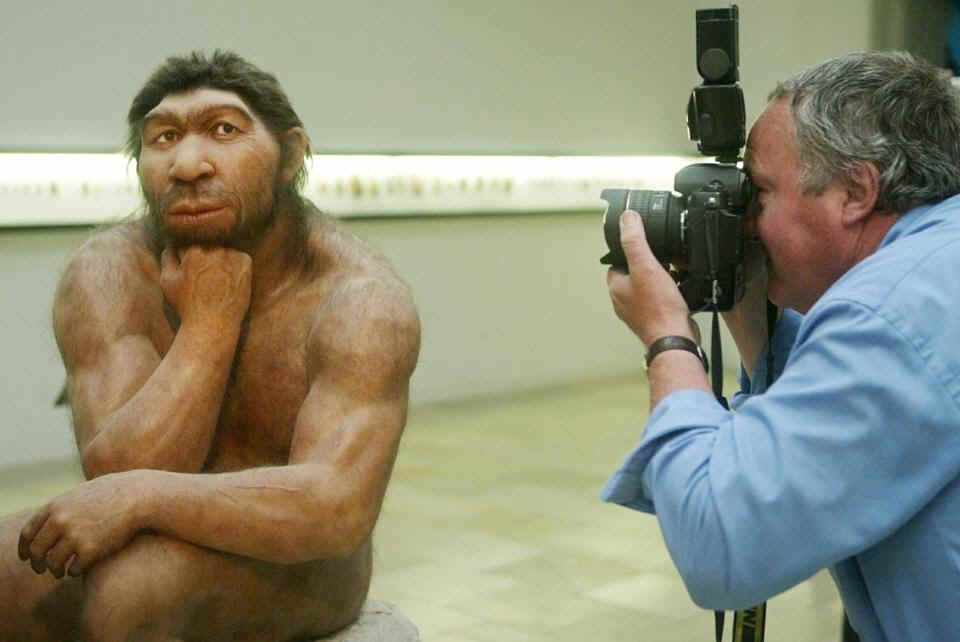

“We used to have a very derogatory view of the abilities of Neanderthals,” Shipman said. “But the more we look at what’s going on, the more sophistication there is and the more subtlety there is.” With new scientific tools, the fields of archeology and paleoanthropology have advanced far beyond simply examining artifacts. Scholars can now study Neanderthals’ metabolic energy expenditures and investigate their diets by analyzing bone chemistry. Many long-discovered archeological sites are now undergoing re-dating using more precise methods than those available in the 20th century; that, too, is leading to new insights and information on how and when humans and Neanderthals might have interacted.

“We used to have a very derogatory view of the abilities of Neanderthals,” Shipman said. “But the more we look at what’s going on, the more sophistication there is and the more subtlety there is.” With new scientific tools, the fields of archeology and paleoanthropology have advanced far beyond simply examining artifacts. Scholars can now study Neanderthals’ metabolic energy expenditures and investigate their diets by analyzing bone chemistry. Many long-discovered archeological sites are now undergoing re-dating using more precise methods than those available in the 20th century; that, too, is leading to new insights and information on how and when humans and Neanderthals might have interacted. From

the time I arrived with my friend Clara to meet Javier in this state

capital city of 125,000 until the moment she and I reluctantly drove out

of town, we were delighted by everything we experienced in Zacatecas.

Three days were not nearly enough time to really savor its Colonial

pleasures. The simple 4-hour drive northeast from Guadalajara to

Zacatecas makes this trip one that we can repeat often—and we

certainly want to go again soon.

From

the time I arrived with my friend Clara to meet Javier in this state

capital city of 125,000 until the moment she and I reluctantly drove out

of town, we were delighted by everything we experienced in Zacatecas.

Three days were not nearly enough time to really savor its Colonial

pleasures. The simple 4-hour drive northeast from Guadalajara to

Zacatecas makes this trip one that we can repeat often—and we

certainly want to go again soon.

The

Pedro Coronel Museum is named for one of the foremost Mexican

painters and sculptors of the 20th Century, and a zacatecano. The

massive and eclectic art collection of this older Coronel brother

(1923-1985), is housed in a huge colonial building which has been at

various times in its history a Jesuit college, a Dominican convent,

early military headquarters, and a jail. Room leads to room, and each is

filled with treasures.

The

Pedro Coronel Museum is named for one of the foremost Mexican

painters and sculptors of the 20th Century, and a zacatecano. The

massive and eclectic art collection of this older Coronel brother

(1923-1985), is housed in a huge colonial building which has been at

various times in its history a Jesuit college, a Dominican convent,

early military headquarters, and a jail. Room leads to room, and each is

filled with treasures.

The Francisco

Goitia Museum is housed in the state governor's former mansion,

located a longish walk or short cab ride from the historic center of the

city. Two huge rooms of the museum house works by Zacatecas artists

Julio Ruelas, Pedro and Rafael Coronel, Manuel Felguérez and others.

Another illustrious zacatecano, Francisco Goitia (1882-1960) has been

compared to the best European painters. Several downstairs rooms are

devoted to Goitia's haunting paintings. Up-and-coming younger Mexican

artists are often invited to exhibit in the second floor rooms.

The Francisco

Goitia Museum is housed in the state governor's former mansion,

located a longish walk or short cab ride from the historic center of the

city. Two huge rooms of the museum house works by Zacatecas artists

Julio Ruelas, Pedro and Rafael Coronel, Manuel Felguérez and others.

Another illustrious zacatecano, Francisco Goitia (1882-1960) has been

compared to the best European painters. Several downstairs rooms are

devoted to Goitia's haunting paintings. Up-and-coming younger Mexican

artists are often invited to exhibit in the second floor rooms.

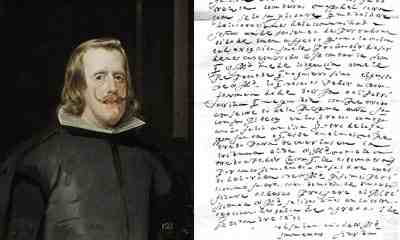

Ángel

Custodio. Aunque quizás usted no lo conozca, hay un pequeño principado

en medio del Atlántico que tiene una curiosa historia y que os contaré

tal como yo la he conocido.

Ángel

Custodio. Aunque quizás usted no lo conozca, hay un pequeño principado

en medio del Atlántico que tiene una curiosa historia y que os contaré

tal como yo la he conocido.