|

The teaming up of United Farm Workers founder Cesar Chavez and Sen.

Robert Kennedy marked an important moment in the fight for the rights of

Latinos in America, a time in history brought to life by a film

biography of Chavez, says James DiEugenio.

In

1996, with great fanfare – and under the influence of political

adviser Dick Morris –

President Bill Clinton signed the largest welfare “reform” bill of

the last 35 years. It was so harsh toward recipients that many

speculated that not even Ronald Reagan would have signed it. But

Clinton, as a titular Democrat, had the cover to do so. Many commented

at the time that this act demonstrated that the Arkansas governor’s

association with the “centrist” Democratic Leadership Council was

not just cosmetic.

Upon

signing the bill, Clinton utilized the words of the late Robert Kennedy,

quoting the liberal icon as saying that work is what the United States

is all about; we need work as individuals and as citizens, as a society

and as a people. When Rory Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy’s youngest daughter,

heard this invocation of her father’s name to support a law that would

hurt the poorest and most disadvantaged people in America, she

immediately called Peter Edelman, who had been a legislative assistant

to Kennedy when he was a senator.

Edelman,

who was working for Clinton as assistant secretary for Health and Human

Services, resigned in protest against the new law. A year later, the

Harvard-educated lawyer wrote a blistering essay about

the “reform” bill and Clinton’s role in it. Five years later,

Edelman explained that not only was the bill a bad one but he was

outraged at Clinton’s use of his former boss’ name in signing it.

Edelman

wrote, “President Clinton hijacked RFK’s words and twisted them

totally. By signing the bill, Clinton signaled acquiescence in the

conservative premise that welfare is the problem — the source of a

culture of irresponsible behavior,” while RFK envisioned a large

American investment to guarantee that people actually could get

decent jobs.

Kennedy

wanted both protections for children and outreach to those who could not

find jobs. In other words, he wanted to do something big about ending poverty.

(See the introduction to Edelman’s book, Searching for

America’s Heart.)

RFK

and Justice

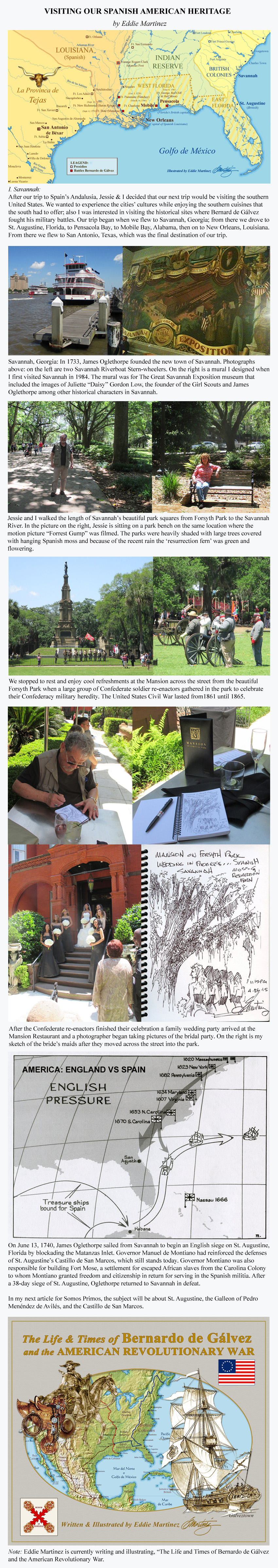

Perhaps

nothing illustrates the difference between the Democratic Party now and

then than Edelman’s role in getting Sen. Kennedy to Delano,

California, in 1966. It’s a story Bill Clinton probably knew about,

but – to my knowledge – never mentioned in public.

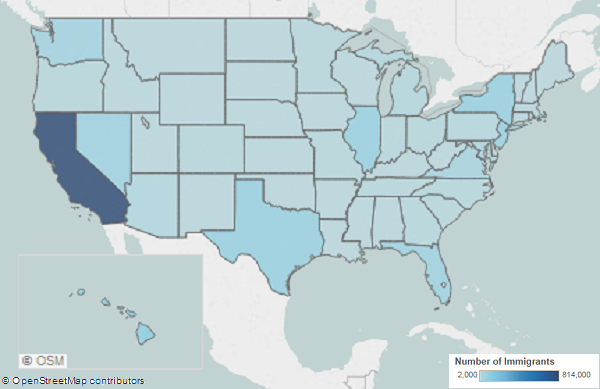

Kennedy

had been serving on a subcommittee of the Senate Labor Committee that

dealt with the plight of migrant workers. That is, people largely from

either Asia or Central America who worked the huge fruit and vegetable

farms in California and other southern states for the large agribusiness

owners.

Prior

to 1965, these workers had no real labor rights. Because of a strong

agribusiness lobbying effort, the minimum wage law did not apply to

them. Neither did child labor laws or collective bargaining statutes.

The national media had only once noticed their plight – in late 1960,

when Edward R. Murrow broadcast his famous CBS documentary Harvest

of Shame.

Edelman

and labor leader Walter Reuther convinced Kennedy that his presence was

needed at congressional hearings being held in March 1966 in Delano.

There was a strike going on led by a Mexican-American activist named

Cesar Chavez. Kennedy’s presence there would give Chavez’s movement

some media attention and bolster the spirits of his followers.

Labor

representative Paul Schrade told me that he and Reuther had already been

to Delano and met Chavez, who suggested that Kennedy attend the

hearings. Schrade said he called Jack Conway, who was Reuther’s

liaison to Kennedy’s office, and connected with Edelman, who joined

with Conway in convincing Kennedy to attend the hearings by making the

argument that “These people need you!” (Arthur Schlesinger, Robert

Kennedy and his Times, p. 825)

Though

reluctant, Kennedy finally relented. But even on the plane ride out, he

still wondered why he was going. But, if anything, Edelman

underestimated the attention and aid RFK was about to bestow on Chavez

and the farm workers.

Both

the local sheriff and the district attorney were there to testify. As

Kennedy either knew, or was about to learn, both men were in the pocket

of the wealthy landowners. With cameras running and reporters in

attendance, a famous colloquy took place between Kennedy, who had

served as Attorney General of the United States, and Sheriff Leroy

Galyen of Kern County.

Galyen: If

I have reason to believe that a riot is going to be started because

somebody tells me that there’s going to be trouble if you don’t stop

them, then it’s my duty to stop them.

Kennedy:

So then you go out and arrest them?

Galyen:

Yes, absolutely.

Kennedy:

Who told you they’re going to riot?

Galyen:

The men right out in the fields that they were talking to says, “If

you don’t get them out of here, we’re going to cut their hearts

out.” So rather then let them get cut, you remove the cause. …

Kennedy:

This is an interesting concept. … Someone makes a report about someone

getting out of order… and you go in and arrest them when they

haven’t done anything wrong. How can you go in and arrest somebody and

they haven’t violated the law.

Galyen:

They’re ready to violate the law, in other words….

At

this point, Kennedy cracked up and laughter enveloped the proceedings.

Kennedy:

Could I suggest in the interim period of time … the lunch period …

that the sheriff and the district attorney please read the Constitution

of the United States.

When

the hearing was over, Kennedy met Chavez outside and told him that he

supported the strike. The senator then joined Chavez on the picket line.

Chavez felt protective of Kennedy, wondering if he wasn’t going too

far too fast. For instance, when a reporter asked RFK if “the Huelga”

(the strike) may be communist inspired, Kennedy instantly replied with:

“No, they are not communists. They’re struggling for their

rights.” (ibid, p. 826)

What

RFK Brought

As

Dolores Huerta, another United Farm Workers founder, noted, “Robert

didn’t come to us and tell us what was good for us. He came to us and

asked two questions: What do you want? And, how can I help? That’s why

we loved him.”

And

as Chavez later said about RFK’s appearance there, “He immediately

asked very pointed questions of the growers; he had a way of

disintegrating their arguments by picking at very simple questions. So

he really helped us … turned it completely around.” (ibid)

As

Edelman later said about Kennedy’s flight into Delano, “Something

had touched a nerve in him. Always, after that, we helped Cesar Chavez

in whatever way we could.” (ibid, p. 827) As Kennedy saw it, Cesar

Chavez was doing for Hispanics what Martin Luther King Jr. was doing for

black Americans, “giving them new convictions of pride and

solidarity.” (ibid)

Kennedy

called on labor leaders to help Chavez organize the migrants. It was the

beginning of a friendship that lasted for more than two years until

Bobby Kennedy’s assassination in Los Angeles after winning the

California primary on June 6, 1968.

When

Kennedy was shot at the Ambassador Hotel, Kennedy had Dolores Huerta on

the podium with him. He had thanked her and Chavez for mobilizing the

voters in Central California. Chavez then served as an honorary

pallbearer at Kennedy’s funeral service.

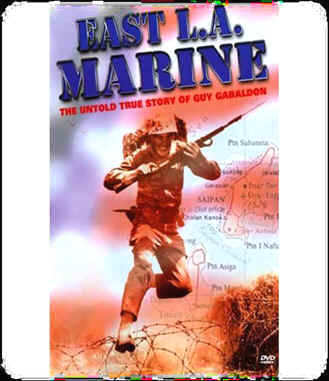

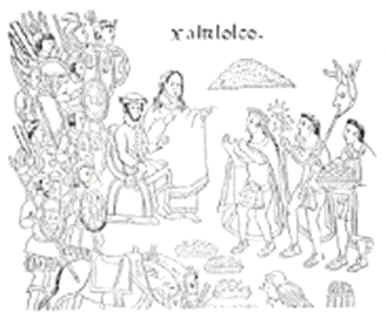

The

humorous scene between Galyen and RFK is depicted in the film Cesar

Chavez: History is Made One Step at a Time, which was released

last year in theaters but which got so little media push and publicity

that I didn’t see it. But a Mexican-American friend of mine advised me

to get it on Netflix or from Red Box. “Jim, it’s at least as good as Selma”

– and she was right.I

actually think it’s better than Selma, but

lacked an Oprah Winfrey/Brad Pitt producing team to promote it.

Both

movies focus on an iconic leader representing an oppressed group of

Americans, withSelma centered on Dr. King. And as

Kennedy noted, Chavez was probably the closest role model that the

Hispanic community has in comparison to King.

Chavez

did face a David-and-Goliath struggle that, in some ways, was comparable

to King’s accomplishments. King’s opponent was the system of racial

segregation that replaced slavery across the South after the Civil War

and the failure of Reconstruction. Segregation was ingrained in nearly

every aspect of Southern life and culture – and was enforced by both

law and violence.

The

Lords of Agribusiness

Chavez’s

opponents were the omnipotent lords of California agribusiness, which

was the largest industry in the state. They dominated the area from

north of Santa Barbara to approximately south of San Jose. When one

drives that stretch of the Golden State Freeway, one can see that the

huge expanse is largely made up of agricultural fields.

The

owners of the fields felt their profits relied upon maintaining the pose

of being farmers, but they were really running a large industry.

Privately they did not refer to themselves as farmers, but rather as

ranchers, growers or agribusiness men. (See Chapter 1 of So

Shall Ye Reap, by Joan London and Henry Anderson)

There

was good reason for that. In 1970, the average farm size in California

was over 700 acres; twice the national average. The average sales price

for a farm was over $300,000; five times the national average. The top

2.5 percent of the industry accounted for the employment of 60 percent

of the migrant labor force.

As

authors London and Anderson point out, this type of wealth allowed the

growers to employ a phalanx of lawyers, PR men, and state and federal

lobbyists – all of it in the cause of preserving and disguising their

dominance over their cheap and plentiful workforce.

With

this kind of power at their disposal, the growers took advantage of laws

that allowed them to claim the government subsidies that sought to

sustain average farmers. For example, irrigation water was delivered to

them at a fourth of what it should have cost because they took advantage

of a subsidy that was reserved for farms of 160 acres or less in size.

As

London and Anderson revealed, the growers rigged the system to achieve

this by making trusts of their properties and partly holding their land

in title to their wives, sisters, daughters, sons, nephews and any other

relatives they could find. They also intervened with the state

government in Sacramento to make their industry exempt from unemployment

insurance and benefited further because only a very small minority of

the farm workers were signed up for Social Security. Thus, there were

very few records of these farm workers who really were transients.

For

30 years, until 1967, agricultural workers also were excluded from the

milestone Fair Labor Standards Act, meaning they were not subject to

minimum wage laws or overtime regulations. Almost all of them worked on

a piecework scale based on how much fruit or how many vegetables they

picked.

Both

Sacramento and Washington excluded agribusiness from the Wagner Act of

1935, which was perhaps the most far-reaching of New Deal legislation

governing worker/employee relations. Without its application, the

growers did not have to recognize collective bargaining efforts and were

free to terrorize organizers who also faced the fact that local law

authorities that were on the growers’ side.

Seeking

Out Labor

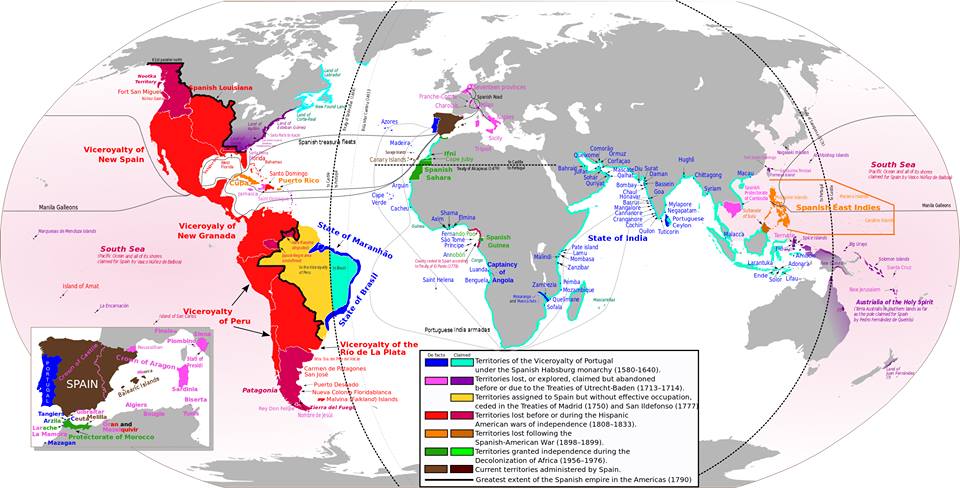

In

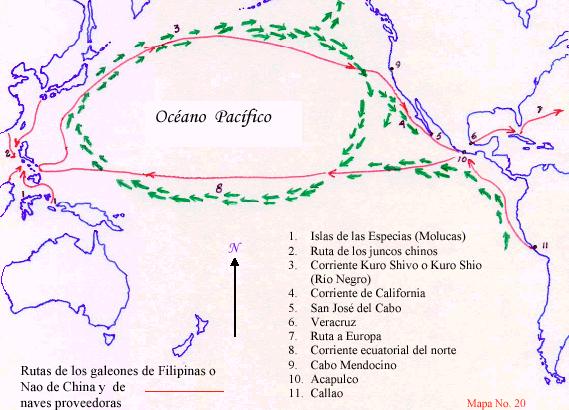

addition to all of this, the growers went looking for minority groups at

home and abroad who they could exploit – sometimes as distant as the

Far East but, after the Mexican Revolution, there was a steady stream

from the south both available and exploitable. This was made legal by

the bracero program, a diplomatic agreement with Mexico permitting the

importation of temporary manual labor into the U.S. By 1945, because of

claims of a labor shortage brought on by World War II, there were 50,000

braceros in the California fields.

As

London and Anderson note, the growers were so powerful that they were

allowed to exempt their workers from Selective Service and use prisoners

of war in their fields. After Ronald Reagan’s election as California

governor in 1967, he showed his appreciation for the growers’

huge campaign donations by letting them use prison convicts for work,

until the state Supreme Court overturned the order.

What

existed closely resembled a feudal system, down to the workers living in

properties sometimes owned and monitored by the landowners. It was, as

one scribe wrote, a condition of semi-voluntary servitude.

But

politicians like Reagan had no qualms about preserving it. He appointed

growers like Alan Grant to the California Farm Bureau Federation, the UC

Board of Regents, and the State Board of Agriculture. From his lofty

perch, Grant saw no problem with the system as it was and no need for

unionism in agriculture. As he famously said, “My Filipino boys

can come to my back door any time they have a problem and discuss it

with me.”

As

with Dr. King, there was a history of organizing attempts for Chavez to

look back on. After violence broke out in 1913, two organizers were

jailed. And six years later, the Criminal Syndicalism Act was passed in

California, essentially making union organizing a criminal act.

During

the Great Depression, some strikes were led by communists, so

agribusiness later used red-baiting and violent tactics to crush

strikes. Under the Criminal Syndicalism Act, several strike leaders were

arrested, two were killed, and over 20 were wounded – violent tactics

that persisted until 1939, condoned by local authorities and hailed by

the local press barons.

This

anti-unionism was endorsed by Richard Nixon, who was elected to Congress

from California in 1947 and was making his reputation as a red-baiter.

In 1950, during a strike in the Delano area, the giant DiGiorgio ranch

hired strikebreakers, a practice that Nixon endorsed, signing a document

asserting that farm workers had been properly excluded from labor laws.

“It

would be harmful to the pubic interest and to all responsible labor

unions to legislate otherwise,” Nixon stated, a position that became

known as the Nixon Doctrine and helped turn that strike around in favor

of the growers.

The

strike was called off later in 1950 after court orders limited

picketing, boycotting and the importation of assistance from other

unions. One of the young men on the picket line nearby was Cesar Chavez.

Escaping

Violence

Chavez’s

grandparents came to America to escape the violence of the Mexican

Revolution. Cesar was born in Arizona in 1927. His family moved to

California in 1938 and first lived out of their car, then under a tent.

As he later related, sometimes they would eat wild mustard seeds just to

stay alive. His family then worked as migrant farm laborers under the

influence of local contractors. They would move up and down the state

following plant harvests.

Chavez

dropped out of school at age 14 in the eighth grade and became a

full-time worker in the fields. In his early 20s, he married Helen

Fabela and in 1949 they had the first of their eight children. With a

young family, he decided to leave the shifting tides of the migrant

worker stream and moved to San Jose. In season, he harvested delicacies

like apricots. In the offseason, he worked in lumberyards.

His

father, Librado, had been active in union organizing and favored

eventual affiliation with the CIO rather than the AFL. The CIO was

Walter Reuther’s union. Young Cesar would sit in on these discussions

and learn as he went. He was also stung by the whip of racism. In his

teens, he remembered being removed from a movie theater for violating

segregated seating rules.

But

the single event that probably changed Chavez’s life the most was the

night a priest named Father McDonnell knocked on the door of his home.

Fathers Donald McDonnell and Thomas McCullough were famous in the area

as the “priests to the poor.” The two divided up the central part of

the state and visited, by their own estimate, about a thousand farm

labor camps. Very early they realized that the growers would never

divide up their farms and sell them to the workers, so the only way to

achieve any justice or dignity for the migrants was through a union.

In

1952, Fred Ross visited the Stockton area from an agency called the CSO,

or Community Service Organization, an offshoot of Saul Alinsky’s

Industrial Areas Foundation. The group’s idea was to recognize central

issues and then build local alliances finding common approaches to

address the issues. Alinsky hired Ross to organize Mexican-Americans in

the Los Angeles area, and – after considerable success – Ross

shifted north to San Jose.

The

knock on the Chavez door was part of a Ross/McDonnell cellular approach,

called the house meeting. In a three-week period, Ross and

McDonnell would visit several houses each night. At the end of the three

weeks, they would then have a larger meeting at one of the bigger homes

to include all the people they talked to who were interested in the

cause identified by the CSO. They would elect temporary officers

and send the people out to knock on more doors, leading eventually to a

local chapter of the CSO.

The

night that Ross met Chavez, Ross reportedly wrote in his journal, “I

think I found the guy I’m looking for.”

Ross

ended up hiring Chavez to work for the CSO at $35 per week. In 1953, he

became a statewide organizer, working from northern California, south to

Oxnard. Chavez and Huerta, whom Ross also recruited, built the state CSO

into a coalition of 22 chapters in California and Arizona, concentrating

on getting farm workers state disability insurance and signing up as

many as they could for Social Security benefits. These developments

meant the growers had to keep files and records on their workers.

Expanding

the Fight

The

next target for Ross, Chavez and Huerta was to end the bracero program,

which they finally did at the end of 1964. But there was a problem

Chavez had with the CSO, which would not commit to an all-out push to

organize and unionize the farm workers of California. Chavez resigned

and took his life savings of $900 out of the bank. He moved to Delano,

explaining that “My brother lived there, and I knew that at least we

wouldn’t starve.”

Chavez

started organizing the local farm workers, calling his new agency the

Farm Workers Association. He deliberately avoided the word “union,”

which he knew was offensive to the growers. He also borrowed money from

a friend to open up a credit union and offered those who joined

preferential rates on insurance. By 1964, he had enough workers paying

dues that he could devote all his energies to building the union.

In

1965, Chavez went on the offensive. He called a rent strike against the

Tulare Housing Authority. He then called two strikes against small

growers. He won and the strikers were rehired. But the greatest conflict

of Chavez’s career — the one Bobby Kennedy enlisted in – was the

massive farm workers’ strike from 1965 to 1970, which expanded into

first a national boycott, and then an international one.

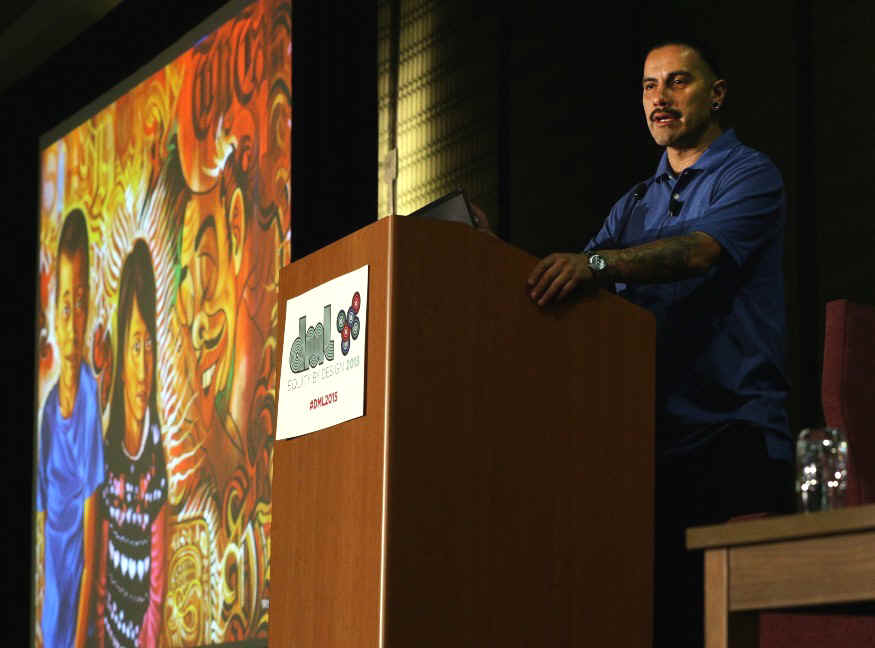

Diego

Luna’s film begins near the end of that boycott. Chavez (played

by Miguel Pena) is in a radio station in Europe trying to expand the

scope of the boycott to England. He begins talking about how he started

out, and the film flashes back to the beginning of his career as an

organizer for CSO near San Jose. Chavez arranges a house meeting so he

can question some of the workers in the area.

The

narrative then jumps to his dispute with CSO over a focus on union

building for farm workers, and we witness his family move from San Jose

to Delano. We see his early struggles to get the farm workers union

going. For example, a visit from the local sheriff, who is surely meant

to suggest Galyen.

But

the picture really picks up momentum with the beginnings of the

five-year strike and boycott, which, ironically, was not started by

Chavez. It was actually begun by Larry Itliong, the leader of Filipino

workers. Itliong chose to have his followers go on strike because the

grape growers in Delano would not pay comparable wages as the growers in

the Coachella Valley.

The

film depicts this moment of crisis very strongly: we see the forces of

the growers standing outside the worker’s barracks in the middle of

the night, demanding, with a loud speaker, that they return to work or

be evicted. The workers refused, and many were evicted.

Itliong

then wrote to Chavez. From past experience, Itliong knew the growers in

Delano would try to recruit strikebreakers from the Hispanic ranks and

asked Chavez to support the walkout by not having the Mexican-Americans

replace his men in the fields.

A

United Front

This

was a portentous moment for Chavez because his efforts were relatively

new, and the union he was leading was not fully formed. But he saw that

what Itliong was asking him to do was to stand up for all farm workers

everywhere — whether they be Asian-Americans or Mexican-Americans.

Chavez argued for backing Itliong and carried the day in the Union Hall.

Although the dynamics behind the Filipino walkout are skimped, the scene

with Chavez leading the argument in the hall is vividly depicted in the

film.

On

Sept. 16, 1965, Chavez and his workers joined the Filipino picket line.

For all intents and purposes, this was the beginning of the five-year

strike, called La Huelga. When the boycott was added, Chavez called it

La Causa.

Realizing

that the stakes had been raised by the alliance of Chavez and Itliong,

the growers started revving up their battery of weapons. First they used

the legal venue, going to court to get injunctions against picketing.

They cited the criminal syndicalism laws to disallow Chavez from

speaking to his followers on a bullhorn. The local courts were so rigged

that they even forbade the strikers to use the word Huelga. The growers

knew these perverse decisions would be reversed on appeal, but they

thought they could outlast the farm workers.

If

it would have been anyone besides Chavez and Itliong, that may have been

the case. But as the film carefully notes, Chavez had hired a capable

attorney to beat back these ridiculous rulings, a man named Jerry Cohen,

who got Chavez, his wife, and Huerta out of jail.

The

film next depicts the beginning of the boycott. Chavez started small,

deciding to attempt to boycott just one winery. But he realized that he

would need allies to spread the word. So, he had his followers perform

outreach to sympathetic leftist groups like students and civil rights

advocates.

In

another good scene, the film shows the effectiveness of this boycott and

how it began to split the ranks of the growers. Julian Sands plays the

director of the boycotted company, with John Malkovich as the

representative of the growers’ association. Malkovich asks Sands not

to give in, but as Sands makes clear, he really did not have a choice.

The boycott was hurting sales too much. (Malkovich also executive

produced the film.)

Mixing

black-and-white newsreel film with a reenactment, the picture next

depicts the appearance of Sen. Robert Kennedy at the Delano hearing.

Luna found an actor named Jack Holmes who has a strong natural

resemblance to Bobby Kennedy. However, the film underplays this

remarkable moment by not showing the bonding that took place afterwards

between the two men.

But

Luna does show the climactic event that took place after Kennedy left.

Borrowing a page from Gandhi and King, Chavez organized a 245-mile walk

from Delano to Sacramento. Luna’s depiction of this event briefly

includes the skits that playwright Luis Valdez would prepare for the

protesters to watch at night. These were almost always satiric in nature

and meant to caricature the arrogance and insensitivity of the growers.

The

main intent of the march was to get California Gov. Pat Brown to push a

bill through the legislature that would give agriculture workers the

right to organize. That bill eventually did pass, but it was later under

the governorship of Pat Brown’s son Jerry.

The

23-Day Fast

No

film about Chavez would be complete without his 23-day fast over the

escalating violence used by the growers to harass his followers. Chavez

was also disturbed by the failure of the farm workers to refrain from

retaliation. Chavez only drank water during this period and – although

Chavez did attract much attention to his efforts – many thought he had

endangered his health. Finally, Bobby Kennedy arrived to convince Chavez

to stop and take Holy Communion with him.

The

film does a nice job in playing off the Holmes/Kennedy scenes with the

newsreels of Ronald Reagan attacking both Chavez and his union. After

Kennedy leaves, we watch as Reagan attacks the grape boycott as immoral,

and he accuses Chavez of using threats and intimidation tactics against

the grape growers.

Luna

and his scriptwriters do an even better job with the assassination of

Robert Kennedy. We watch as Chavez pulls his car over to hear a radio

bulletin about Kennedy’s assassination. Luna then cuts to Kennedy’s

requiem at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The director is careful to include

a shot of presidential candidate Richard Nixon in attendance.

This

will strike the theme that, with RFK dead, Chavez lost a key ally in the

political world. The growers increased their violent tactics. And, with

Nixon in the White House, they thought they had a solution to the

national boycott because Nixon facilitated agreements that allowed them

to ship their grapes to Europe to be sold.

But

Chavez was planning for this maneuver. Because of the expanded exposure

of his work in the mass media — a Time Magazine cover

for instance — he had become something of a celebrity. So, the

film picks up where it began: with Cesar speaking on the radio in

England, promoting the boycott abroad. He also made alliances with

unions there to not handle U.S. grapes.

And

in what is probably the highlight of the film, Luna shows Chavez and his

new English friends dumping unshipped grapes into the Thames River, a

reverse Boston Tea Party. The film crosscuts this with a montage of

Malkovich on his empty ranch: one with no workers, abandoned tractors,

and unmoved grapes spoiling in crates.

Being

checkmated abroad was the last straw for the growers. In July 1970, many

of these agribusinesses decided it was time to recognize the United Farm

Workers, even if it meant signing contracts with Chavez. The film ends

with that historic signing.

The

Chavez/Kennedy/Itliong struggle was truly a case of the underdog winning

out through sheer determination and courage. The deck was completely

stacked against their cause, but with help from good people like RFK,

Reuther and Pat Brown, Cesar Chavez did make a difference and achieved

what no one had done before him.

There

have been surprisingly few films made about Chavez, even though his life

was full of both epic and personal drama. I only know of two

documentaries: Viva LaCausa and The Fight in

the Fields. The latter PBS documentary goes beyond the time

limits of Luna’s film and confronts some of the problems the UFW had

later. After all, it was not easy to maintain what Chavez achieved with

Ronald Reagan in the White House and George Deukmejian in the

governor’s mansion in Sacramento.

Luna

has made a good film, one with a strong underlying message. Chavez was

not handsome and photogenic like JFK was. He was not anywhere near

the speaker that King was. And he did not have the wonder drug of

charisma, as did Malcolm X. That Chavez achieved what he did with so few

natural gifts was a great testament to what an ordinary man can do

when touched with the right moment and the right inspiration.

|

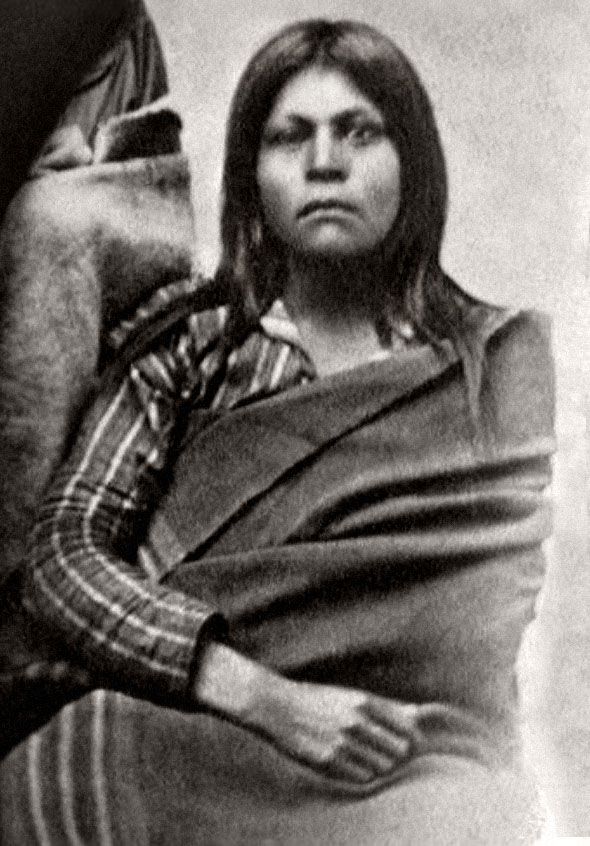

Mimi Ko Cruz

Mimi Ko Cruz

English

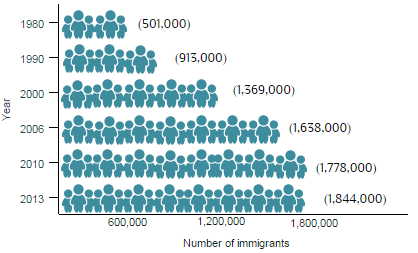

Proficiency on the Rise Among Latinos - U.S. Born Driving Language Changes

English

Proficiency on the Rise Among Latinos - U.S. Born Driving Language Changes

Frida

Kahlo is someone who many of us at Latino USA love.

Frida

Kahlo is someone who many of us at Latino USA love.

Dr.

Felipe de Ortego y Gasca, Ph.D.,

Dr.

Felipe de Ortego y Gasca, Ph.D.,

However, it is well-known that Valentino was an accomplished dancer before he arrived in California. In fact, as I understand it, his dancing was how he supported himself, flirting with smitten wealthy women.

There are two possibilities to explain the story: either it was not Valentino but some other actor that was mistaken for him by Great Aunt Cecilia, who would have been about 10 or 11 years old when she watched the couple dance, or Jovita was not teaching Valentino but rehearsing with him. Could she have been preparing him for the famous tango scene in the classic film "The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse" (1921)?

However, it is well-known that Valentino was an accomplished dancer before he arrived in California. In fact, as I understand it, his dancing was how he supported himself, flirting with smitten wealthy women.

There are two possibilities to explain the story: either it was not Valentino but some other actor that was mistaken for him by Great Aunt Cecilia, who would have been about 10 or 11 years old when she watched the couple dance, or Jovita was not teaching Valentino but rehearsing with him. Could she have been preparing him for the famous tango scene in the classic film "The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse" (1921)?

Rafael

Ojeda

Rafael

Ojeda

Joe

Olvera is a long-time journalist whose latest book is - Chicano Sin

Fin: Memoirs of a Chicano Journalist

Joe

Olvera is a long-time journalist whose latest book is - Chicano Sin

Fin: Memoirs of a Chicano Journalist

Hadley Meares is a writer, historian, and singer who

traded one Southland (her home state of North Carolina) for another.

She is a frequent contributor to Curbed and Atlas Obscura, and leads

historical tours all around Los Angeles for Obscura Society LA.

Hadley Meares is a writer, historian, and singer who

traded one Southland (her home state of North Carolina) for another.

She is a frequent contributor to Curbed and Atlas Obscura, and leads

historical tours all around Los Angeles for Obscura Society LA.

and

yours alone. Others may walk it with you, but no one can walk it for

you.

and

yours alone. Others may walk it with you, but no one can walk it for

you. 15.

Keep yourself balanced. Your Mental self, Spiritual self,

Emotional self, and Physical self, all need to be strong, pure and

healthy. Work out the body to strengthen the mind. Grow rich

in

15.

Keep yourself balanced. Your Mental self, Spiritual self,

Emotional self, and Physical self, all need to be strong, pure and

healthy. Work out the body to strengthen the mind. Grow rich

in

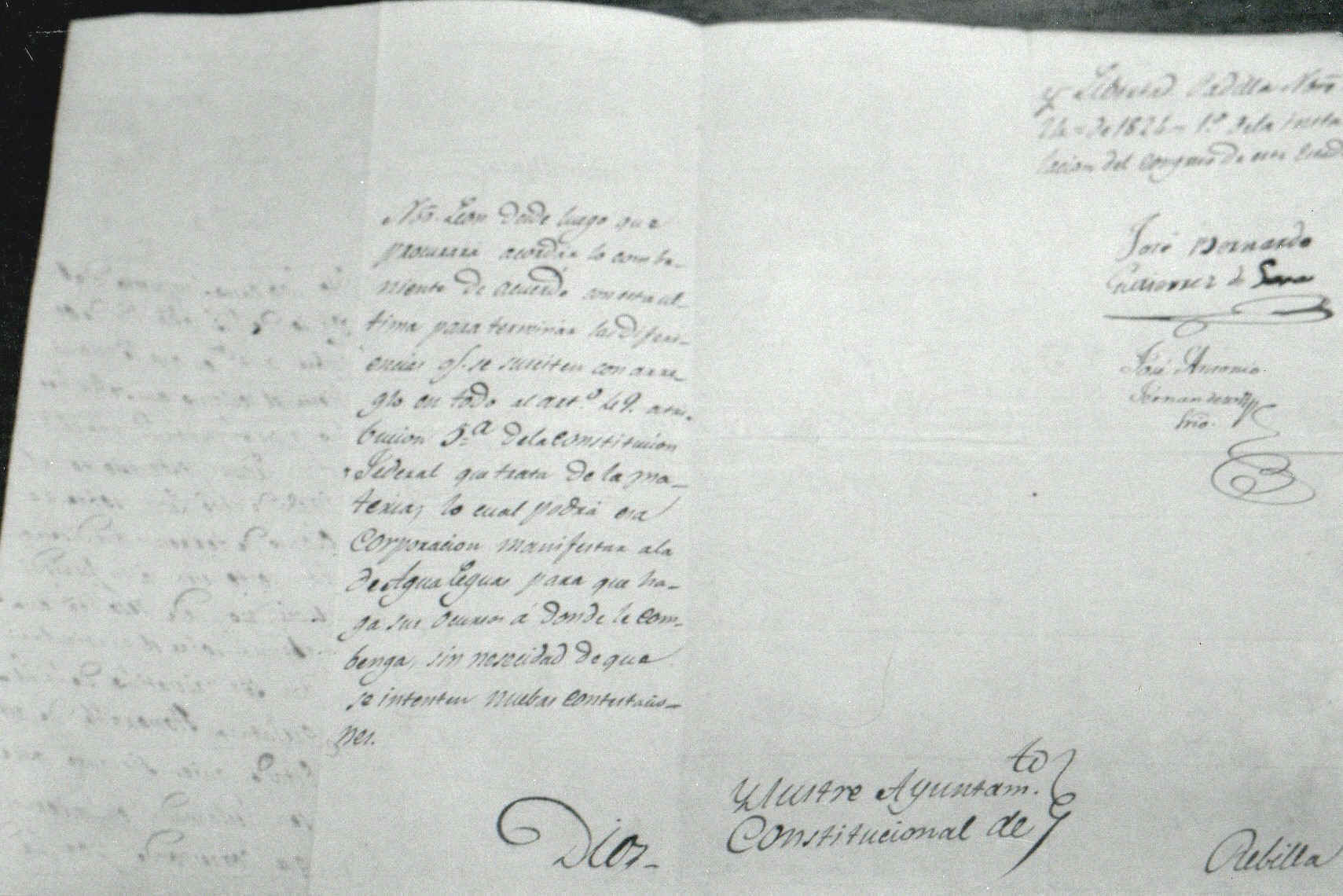

Fifty

years ago the Puerto Rican community in New York

City achieved a major milestone, the culmination of

efforts since 1899 to open the vote to Puerto Rican

voters on equal terms.

Fifty

years ago the Puerto Rican community in New York

City achieved a major milestone, the culmination of

efforts since 1899 to open the vote to Puerto Rican

voters on equal terms.