This is a story about a Christmas in China after World War II and

how the world changed for me as a consequence of that Christmas.

Hard to believe that almost six decades have passed since VJ Day

(Victory in Japan, August 14, 1945) and the end of hostilities for

World War Two.

By

Christmas of 1945 the war had been over more than four months, just

after President Truman had authorized dropping a 20 kiloton atomic

bomb equivalent to 12,500 pounds of TNT on Hiroshima on August 6 and

a 5 ton atomic bomb equivalent to 22,000 pounds of TNT on Nagasaki

on August 8.

We

did not learn about the atomic bombs until some days after the

bombings when we read the news in the Stars and Stripes, the

Pacific edition of the daily newspaper published by the Armed

Forces: the first bomb–“Little Boy”–was dropped on Hiroshima

at 8:15 a.m. on August 6 by the Enola Gay, a B-29 bomber piloted by

Lawrence Tibbett; and a second bomb–”Fat Man”–was dropped on

Nagasaki the night of August 8 by a B-29 bomber from Tinian piloted

by Charles Sweeney.

August

6, 1945 was not a particularly portentous day. The battle for Iwo

Jima in the winter of that year (February 19) and the assault on

Okinawa later that spring (April 1) were still fresh in memory. The

full force of President Truman’s decision to drop nuclear bombs on

Japan would not impact the American conscience until much later in

the future. In August of 1945, however, Americans and, particularly,

American troops in the Pacific welcomed the news that armed conflict

with Japan had come to an end with its unconditional surrender.

That

August American GI’s were poised in the Pacific awaiting orders

for a massive assault on Japan. Though weary, American troops were

ready for the “last campaign” starting with the island of Kyushu

in Operation Downfall led by General Douglas MacArthur and

Admiral Chester Nimitz.

A million men were reportedly massed for that operation in which

President Truman and American military leaders expected more than

250,000 deaths and 500,000 maimed or wounded. By comparison, the

battle for Iwo Jima cost 5,300 American lives and 16,000 wounded;

the battle for Okinawa ended with 7, 300 American dead and 32,000

wounded. The total loss of American lives during World War II was

405,000.

The

atomic bombs saved us from what would surely have been an

“Armageddon” to vanquish Japan unconditionally. We had been

spared the last campaign. The United States had been at war 44

months; and I had served for more than half that time. I would serve

a little longer before accumulating enough points for discharge.

No American and, perhaps, none of the scientists who worked on

the bombs had any idea of the biological and genetic devastation

potent in their creations, though J. Robert Oppenheimer (father of

the bomb) is reported to have said “I am become death” when he

heard the news.

In

the Fall of 1945, however, the moral imperatives of life (and of

war) seemed clear and simple. Good had triumphed over evil, no

matter that the victory (like Pandora’s box) had unleashed dark

cosmic forces upon the earth.

Many

of us had little comprehension of the awesome power of those bombs.

Later we would understand that the world had entered the Atomic Age.

And later we would also learn about the Manhattan Project and Los

Alamos. But on that August day when we got the news about Japan

surrendering unconditionally, we thanked God.

Of

course, there’s regret for the havoc wreaked by the

“bombs”--140,000 deaths at Hiroshima; and 70,000 deaths at

Nagasaki. What human would not mourn the loss of such life? But

there’s also regret for the lives lost at Pearl Harbor, and the

lives lost in a string of atrocities committed by Japanese military

forces in their murderous march across Korea, Manchuria, China,

Burma, Malaya, the Philippines, and a host of islands that dot the

expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

I felt ancient at war’s end. War has a way of maturing youngsters,

growing them up quickly. There is also a mantle of invincibility

that cloaks the young, woven of equal parts of arrogance and

ignorance, strands of curiosity, and large patches of naiveté.

It’s a wonderful time of life: full of joy one thinks will last

forever; full of agony that seems interminable.

I

was a Sergeant of Marines then, filled with the exuberance of

victory marking the end of a life and death struggle between the

forces of good and evil, a struggle that claimed 50 million lives

world wide.

I

was 19 years old that August and the fates had kept me from harm

thus far. Just two years earlier, on my 17th birthday, I

had enlisted in the Marines, during the dark, grim days of the war

when victory appeared implausible and the fate of democracy hung in

the balance.

The San Antonio of 1941, where a branch of my

mother’s family settled in 1731, was a place of “brown blood and

white laughter” as I wrote in a poem years later, remembering the

city’s segregated schools and its English-only rules. Though the

war transformed the city economically, a different kind of war

would vanquish the barriers that had made San Antonio a divided

community and strangers of Tejanos in their own land.

At

war, Tejanos showed their mettle, Boys became men. The League of

United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) suspended its annual

conferences for the duration. On the home front, Mexicana Americans

built planes, subs, and gliders; handed out donuts and coffee to

America’s youth training at Fort Sam Houston, Kelly, and Lackland

Air Force bases in San Antonio. Many became air raid wardens. On the

West Side, Tejana mothers placed gold stars in their windows.

On

the day of infamy, I wondered if I could pass for 17, hoping the war

would wait for me. I tried to enlist in the Army in 1942 but was

turned away because I was too young at 15 for military service they

told me even though the country was desperate for troops. I got as

far as the physical before I was found out and turned away with an

admonishment veiling a smile and an encouragement to try again next

year. Did I know, they asked, that I had flat feet? By next year, I

thought, there would be no glory left. But I waited, toughing out

the 9th grade of school. I should have been a Junior but

instead I was a highschool Freshman, two years older than my

classmates because I had repeated the 1st

grade and had been held back in the 4th. I started

public school as a speaker of Spanish in segregated schools and

didn’t improve until I made it to the 5th grade.

In

January of 1943 I tried enlisting in the Navy but was rejected

because of “color blindness,” not because of my age. When I

turned 17 that year, I tried the Marines, color blindness, flat feet

and all. They accepted me, and after boot-camp at Parris Island,

South Carolina, I was assigned to the Marine Air Station at Cherry

Point, North Carolina, from where I was sent to the 8th

and I (Eye) Marine barracks in Washington DC. From there I was

ordered to the Marine barracks at Air Station Quantico, Virginia,

from where I shipped out to the Pacific. After a stop at San Diego

and Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands, I was part of the tail-end of the

last campaigns in the Pacific.

When Japan surrendered, American GI’s in the Pacific were grouped

into those who had earned sufficient points for immediate

return to the states and a victor’s welcome, and those who

didn’t. Wartime service was after all for the “duration” and

the war was not officially over until December of 1946 even though

the fighting had ended more than a year earlier.

Troops

not returned to the states were massed into a force of military

occupation for Japan and those headed for mainland China as an army

of liberation to disarm the Japanese troops in China and to oversee

their evacuation. China

had been occupied by the Japanese since the 30's and at the outbreak

of hostilities had interned the 4th Marines who had been

stationed in Shanghai. China would be freed at last.

The

hop from Okinawa to Shanghai was short. On that rain-washed day I

did not know my journey to China would mark the beginning of my

search for America.

An

early day harbinger of Battlestar Galactica, the ragtag

fleet of American ships trailing up the Yangtze River toward

Shanghai was heralded with cheers of jubilation and gratitude by the

Chinese. “Ding hao!” they shouted. “Ding hao!

Good, good!” But that mood quickly soured when the hive of sampans

crowded the spaces between the ships and the Chinese smiling held

out their hands for some token of largesse signaling our arrival.

What

turned the scene ugly was when the Captain of the U.S.S. Monrovia

ordered the fire-hoses turned on the Chinese clambering up the sides

of the ship trying to get on deck. The Chinese were eager to greet

us, but that greeting was met with disdain by those Americans who

saw the Chinese as nothing more than “gooks” and could not

differentiate them from the Japanese.

The

force of the water hoses sent the Chinese back into the mass of

sampans, some of them falling into the water through the spaces

between the flat dugouts. The scene became a melee when the sailors

decided malevolently to aim their hoses at the people on the

sampans. The Chinese were bewildered. Why would a liberating force

treat them that way? Chinese women screamed as their babies were

flushed out of their hands by the force of the water from the fire

hoses.

What

should have been a celebration became a melee of confusion and

grief. That was not our finest moment. Those images have remained

with me ever since. Little wonder we lost China to Mao Tsetung in

1948, forced to take our troops to Korea. I was gone by then. I left

China in 1946.

But

the specter of that moment did not deter me from savoring the

experience of being in China, the land of Cathay, of Marco Polo and

Genghis Khan. The Yellow Sea washing against a land already ancient

when the sailors of Colon flitted from fleck to fleck looking for

Cipango (Japan) was not yellow but emerald green in the time of my

youth when all my dreams were green. Years later I would realize

what a profound effect that experience in China had on me.

My stay in shanghai was brief. My outfit

moved on. I was assigned to temporary duty with the 6th

Marines in Peking and Tient-sin. I was posted to duty with Marine

Air Group (MAG) 24, First Marine Air Wing at Tsing-tao, a key

airfield in the Japanese occupation of the Shantung Peninsula just

across from Korea.

Tsing-tao

is a port city and at war’s end was once more bustling with the

hum of international trade. In Tsingtao (which sounded like Ching-doh)

I was looked upon with puzzlement. Was I an American Chinese? A Migua

Chinee? They had never seen a Mexican American before. Yes, I

nodded, good-naturedly. “Ding hao, ding hao!” Good, good!

the Chinese responded with smiles of approbation.

Was

I the first Chicano in China? No. Twenty-five years later in El Paso

I would meet a Chicano, Cleofas Callero, who had been a China Marine

in the years between the World Wars. There were probably others

before him.

Some

30 years later, Carlos Guerra, the journalist from San Antonio would

travel to China. So would Patricia Roybal of El Paso and her

husvband Chuck Sutton, heir of he publisher of The Amsterdam News. And in the 80's Rudy Anaya, the Chicano

novelist, from Albuquerque, New Mexico would venture to China and

record his impressions in a work entitled A Chicano in China.

My affection for the Chinese was regarded with mischief as word

spread that the Sarge was a Chink-lover. Fortunately, hierarchy and

rank are powerful investitures in the military, especially the

Marines. The troops may have disliked my affection for the Chinese

but they took orders from me, like them or not. Everyday I dressed

down some troop for dissing the Chinese. They were not our beasts of

burden, though we employed them on the air base as if they were.

In China, American forces rode roughshod over the Chinese,

acting more like Alexander’s Macedonian soldiers than emissaries

of freedom. The Chinese quickly saw me as a friend. I was invited

into their homes. I became good at ping-pong. I went everywhere with

confidence.

American

troops in China, as almost everywhere else, did not carry currency.

Instead we were issued scrip paper money backed by the U.S. armed

forces. Chinese money was out of the question. With inflation,

Chinese money was almost useless. GI’s collected it as souvenirs

or for prospective wallpaper.

The

brothel of “white” Russian women in Tsingtao preferred goods

for their services. Cigarettes were most preferable. Chinese

merchants accepted scrip which they exchanged for currency. In

Peking, Chiang Kais hek was struggling to stabilize the monetary

woes of the country.

One evening, not long after I arrived

at Tsingtao, the base responded to a fire alarm in the city. The

British Officer’s Club had caught fire and needed help in putting

out the blaze. The fear was that the fire would spread into the city

and become harder to control. From the airbase, three runway fire

trucks with foam screamed into the night roaring toward the glow of

the fire in the distance.

As

NCO of the day, I was responsible for dispatching the fire trucks.

The old China Marines used to tell stories about Chinese fire drills

which I didn’t understand until the night of that fire in Tsing-tao.

What

confronted us was both risible and tragic. Attempting to put water

on the fire were Chinese firemen struggling with old-fashioned

wheeled water pumps. One man pumped while the other directed the

hose barely trickling onto the fire. The Chinese firemen smiled

politely as they greeted us. We ushered them out of the way, and

quickly funneled a sheet of foam over the fire. We had arrived just

in time. Though the Chinese firemen could not have contained the

fire, their efforts had given us sufficient time to get there and to

put the blaze out.

I

recognized that the caricature of Chinese ineptness was compounded

by their lack of available technology. Mao Tse tung recognized that

lack also which is why he launched the Chinese Revolution. China had

to enter the modern age despite its legacy as a victim of

colonialism.

The week before Christmas some of the men in my troop wondered if we

could find a Christmas tree in the hills beyond the air base.

“Whadaya think, Sarge?”

“Sure,

why not?” We weren’t prohibited from going into the hills,

though we were counseled to be careful. The Chinese Communists had

been massing in the North and there were reports that some of their

units were heading south.

I

checked out a truck from the motor pool and with a patrol of men

headed toward the rise of hills some four or five miles west of the

base. Once there, we headed off-road toward a clump of Chinese pine

trees and settled on a good-sized tree that we chopped down quickly

and loaded onto the truck. As we were ready to mount up and head

back to the base, one of the men called out, “Sarge, take a

look!” Coming out through the trees were a number of platoon armed

with carbines and wearing drab uniforms with no insignia. The one

who seemed to be the leader came up to the truck, surveyed it,

walked around towards the front where I was standing, all the while

with his finger on the trigger of what looked like a rapid-fire

carbine. His men stayed

at a distance but with fingers at

the ready on the triggers of their weapons.

We

had brought axes not weapons. I was the only one with a sidearm. I

beseeched my men to stay calm. I could see they were nervous. But

they were seasoned men. I mustered a subtle smile as the leader of

the hostiles acknowledged me and proceeded to inspect the cab of the

truck. On the passenger side of the cab lay the book in Spanish I

had been reading off and on for some time: La Vida Tragica, The

Tragic Sense of Life by the Spanish philosopher, Miguel de

Unamuno. Picking up the book, the leader of the arm-ed men who by

that time we had all surmised were Chinese communists, asked: “Y

este libro, de quien es? Whose book is this?” I was startled by the

expression, little expecting a Chinese to speak Spanish, at that

moment and in that place. “Mine,” I said. “Es el mio.”

“Hm,”

he murmured, pursing his lips, studying me intently for a moment. He

put the book back on the seat of the cab and mustering an equally

subtle smile motioned his men back into the anonymity of the woods.

Before disappearing into the trees, the leader turned and with a

most subtle smile, waved. ” I waved back warmly, relieved that the

incident turned out as it had.

“What

was that all about, Sarge?” one of the men asked.

“I

don’t know,” I said. “I don’t know.”

Years

later I would know, years after I had acquired a structure of

knowledge into which to fit that experience. One day, an epiphany, I

understood the significance of that moment in North China and the

Christmas tree incident of that December.

By

then the homecoming parades had all been held and the heroes all

properly heralded. The United States was almost back to normal.

Uniforms with plastrons of medals had been hung in closets for a day

when they would no longer fit. I was ready to begin my search for

America.

The roots of that search lay in China

where I saw “the others” and saw myself in them. Though I had

grown up in a segregated society I had never thought of myself as

“the other.”

But

the war changed me and the way I was to see myself in the context of

the United States. I learned that no matter that Mexican Americans

had won more Medals of Honor than any other ethnic group in

America’s defense, we would have to fight far fiercer battles to

secure for ourselves and our children the fruits of American

democracy.

Though

I had completed only one year of high school, nevertheless on the GI

Bill I went to college after the war at the University of Pittsburgh

where in text after text I studied I did not find myself nor my

people. I did not find my people in the texts I studied at the

University of Texas either where I pursued the Master’s degree in

English. They were also not in the texts I studied at the University

of New Mexico where I completed the Ph.D. in English renaissance

studies, American literature, and Behavioral Linguistics. And

because I could not find Mexican Americans in those texts, my

life’s work became a crusade for their inclusion.

In 1947 the city of Three Rivers, Texas, shamelessly

refused to bury in its municipal cemetery a Mexican American GI

whose body had been exhumed in the Philippines and brought home for

a hero’s burial. Adamantly the white city power brokers would not

yield from their decision. At that point Senator Lyndon Baines

Johnson approached President Truman on the matter and he directed

that Felix Longoria be buried in Arlington Cemetery among the

valiant of the nation.

Out of that incident emerged the American GI Forum, a separate

organization for Mexican American veterans, an organization I

joined. Since then, numerous like incidents have necessitated

creation of many separate Mexican American organizations. It

didn’t need to be that way. Once, we were all brothers-in-arms.

In my search for America, I have often thought of that young Chinese

communist who bade me good luck in a language my country sought to

strip me of. I have thought often of that China of so long ago.

Once, I harbored thoughts of returning to China to look for that

young man who had perhaps read

Unamuno’s Tragic Sense of Life--in Spanish and who at

that moment may have seen me not as a Migua Chinese but as a

literary kinsman.

Who was he? And how had he come to learn Spanish? Was he

perhaps a child of a Chinese Communist who had participated in the

Spanish Civil War of the mid ‘30’s and was now a Maoist? Hum?

The question has remained pervasive for me during all these years.

Thinking back—over the years—the gains have been worth

the struggle. Mexican Americans did their part in World War II. And

in subsequent conflicts as well as prior wars.

This is our country,

too, for we are in the land of our ancestors when this part of the

United States was Mexico; and when it has called we have served.

But I’m still looking for America, in the nooks and

crannies of those years since VJ Day, the end of World War II, and

that Christmas in China.

Copyright

©2001 by the author. All rights reserved

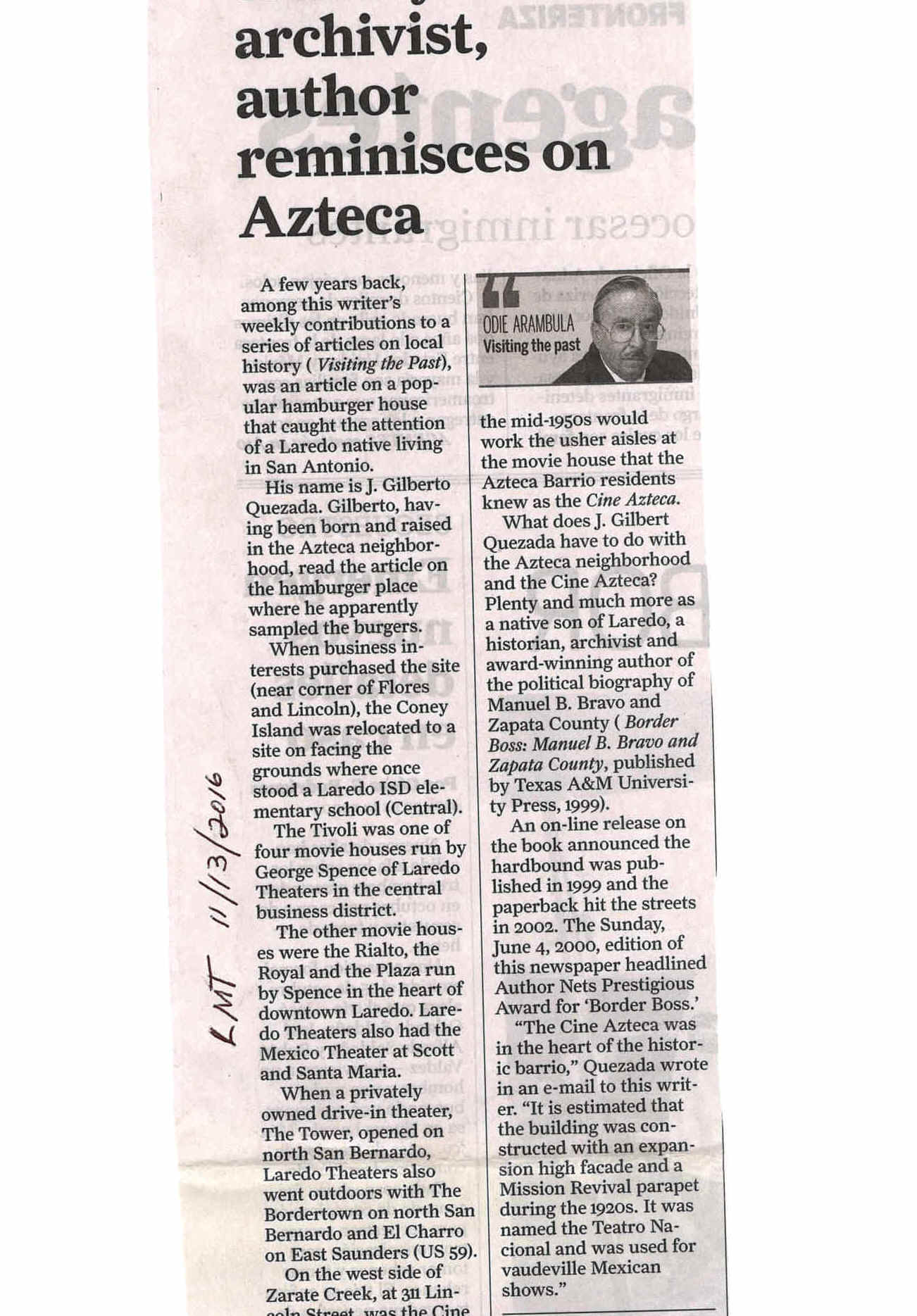

His

tenacious and persistent

His

tenacious and persistent

Judge

Edward F. Butler, Sr. a retired federal

administrative law judge, served as President General Sons of

the American Revolution (SAR) in 2009-2010. He was the Founder &

Charter Grand Viscount General of the Order of the Founders of North

America 1492-1692 in 2012-2014. For several years he has been active

in 32 lineage & heritage groups, including service as Deputy

Governor General of the General Society of Colonial Wars and Vice

President General of the General Society of the War of 1812. He also

served as Governor of the Texas Society Order of the Founders and

Patriots of America and state President of both the Texas Society of

the Sons of the Revolution and First Families of Maryland, where he

also serves nationally as Chancellor General. He has written three

family history books, one of which won the Dallas Genealogical Society

Award in 1997. His first history book about the American Revolutionary

War has already won 5 awards and his latest book just came out.

Judge

Edward F. Butler, Sr. a retired federal

administrative law judge, served as President General Sons of

the American Revolution (SAR) in 2009-2010. He was the Founder &

Charter Grand Viscount General of the Order of the Founders of North

America 1492-1692 in 2012-2014. For several years he has been active

in 32 lineage & heritage groups, including service as Deputy

Governor General of the General Society of Colonial Wars and Vice

President General of the General Society of the War of 1812. He also

served as Governor of the Texas Society Order of the Founders and

Patriots of America and state President of both the Texas Society of

the Sons of the Revolution and First Families of Maryland, where he

also serves nationally as Chancellor General. He has written three

family history books, one of which won the Dallas Genealogical Society

Award in 1997. His first history book about the American Revolutionary

War has already won 5 awards and his latest book just came out.

Numero Veintiuno.- En la Ciudad de

Chihuahua, a las 17 horas 30 minutos del martes 6 de enero de 1931, yo,

Serafin Legarreta, Juez del Registro Civil, hago constar: que he

recibido del Juzgado Segundo de lo Penal, un oficio que a la letra

dice: Al margen un sello, que dice: Juzgado Segundo de lo Penal=

Distrito Morelos. Chih..- Nùm. 35.= al centro: C. Juez del Registro

Civil.=Presente.= Atentamente suplico a Ud. se sirva ordenar sea

inhumado desde luego el cadáver del Norteamericano, que en vida llevò

el nombre de Art Acord, quien según las constancias procesales y

dictamen rendido por los Mèdicos Legistas, de esta Capital, falleció

la madrugada del dìa cuatro del corriente mes, à consecuencia de una

congestión cerebral por alcoholismo. El occiso Art Acord, según

pasaporte que fuè exhibido por los testigos de identificación,

era de treinta y cinco años de edad, soltero, artista de cine,

originario de Steelwater, Okla. Estados Unidos de Amèrica, sin que se

tengan mas datos sobre quienes sean o hayan sido sus padres.=

Levantada que sea el acta respectiva de defunción, agradecerè a Ud.

se sirva remitirme copia certificada de ella para agregarla al

expediente relativo, en el concepto de que el cadáver se encuentra a

su disposición en el Hospital Civil de esta Ciudad.= Protesto a Ud.

Mi atenta consideración.= Chihuahua, enero 6 de 1931.= El Juez 2º de

lo Penal Int.= Augusto Cèsar Dominguez- Rùbrica.= El subscrito Juez

dispuso se verifique la inhumación del cadáver hoy luego, en

el Panteon del Estado, fosa de 1ª. Clase, número 380, mandando se

levante la presente acta, que firma para constancia. Doy fè.= Serafin

Legarreta.

Numero Veintiuno.- En la Ciudad de

Chihuahua, a las 17 horas 30 minutos del martes 6 de enero de 1931, yo,

Serafin Legarreta, Juez del Registro Civil, hago constar: que he

recibido del Juzgado Segundo de lo Penal, un oficio que a la letra

dice: Al margen un sello, que dice: Juzgado Segundo de lo Penal=

Distrito Morelos. Chih..- Nùm. 35.= al centro: C. Juez del Registro

Civil.=Presente.= Atentamente suplico a Ud. se sirva ordenar sea

inhumado desde luego el cadáver del Norteamericano, que en vida llevò

el nombre de Art Acord, quien según las constancias procesales y

dictamen rendido por los Mèdicos Legistas, de esta Capital, falleció

la madrugada del dìa cuatro del corriente mes, à consecuencia de una

congestión cerebral por alcoholismo. El occiso Art Acord, según

pasaporte que fuè exhibido por los testigos de identificación,

era de treinta y cinco años de edad, soltero, artista de cine,

originario de Steelwater, Okla. Estados Unidos de Amèrica, sin que se

tengan mas datos sobre quienes sean o hayan sido sus padres.=

Levantada que sea el acta respectiva de defunción, agradecerè a Ud.

se sirva remitirme copia certificada de ella para agregarla al

expediente relativo, en el concepto de que el cadáver se encuentra a

su disposición en el Hospital Civil de esta Ciudad.= Protesto a Ud.

Mi atenta consideración.= Chihuahua, enero 6 de 1931.= El Juez 2º de

lo Penal Int.= Augusto Cèsar Dominguez- Rùbrica.= El subscrito Juez

dispuso se verifique la inhumación del cadáver hoy luego, en

el Panteon del Estado, fosa de 1ª. Clase, número 380, mandando se

levante la presente acta, que firma para constancia. Doy fè.= Serafin

Legarreta.

It

was 90 yrs ago that Margarito (1898-1973), Juana

(1903-1965), Dolores (1923-1990), Julia (1.16.26), and

our maternal grandfather Juan Vargas (1860-1951/52), whom we

affectionately called papa Juan, crossed the International

Bridge from Ciudad Juárez into El Paso. . .then into California by

way of Yuma.

It

was 90 yrs ago that Margarito (1898-1973), Juana

(1903-1965), Dolores (1923-1990), Julia (1.16.26), and

our maternal grandfather Juan Vargas (1860-1951/52), whom we

affectionately called papa Juan, crossed the International

Bridge from Ciudad Juárez into El Paso. . .then into California by

way of Yuma.

Mom Evangeline was a beauty and a wonderful woman

who was loved by everyone. Her father, Buenaventura (Ben) Romero

Gutierrez called her "Peaches and Cream". Mom, seated

is seated to the left, wearing the white dress and white shoes. We do

not know the lady seated to the right wearing the dark dress.

Mom Evangeline was a beauty and a wonderful woman

who was loved by everyone. Her father, Buenaventura (Ben) Romero

Gutierrez called her "Peaches and Cream". Mom, seated

is seated to the left, wearing the white dress and white shoes. We do

not know the lady seated to the right wearing the dark dress.

El

24 de abril de

El

24 de abril de

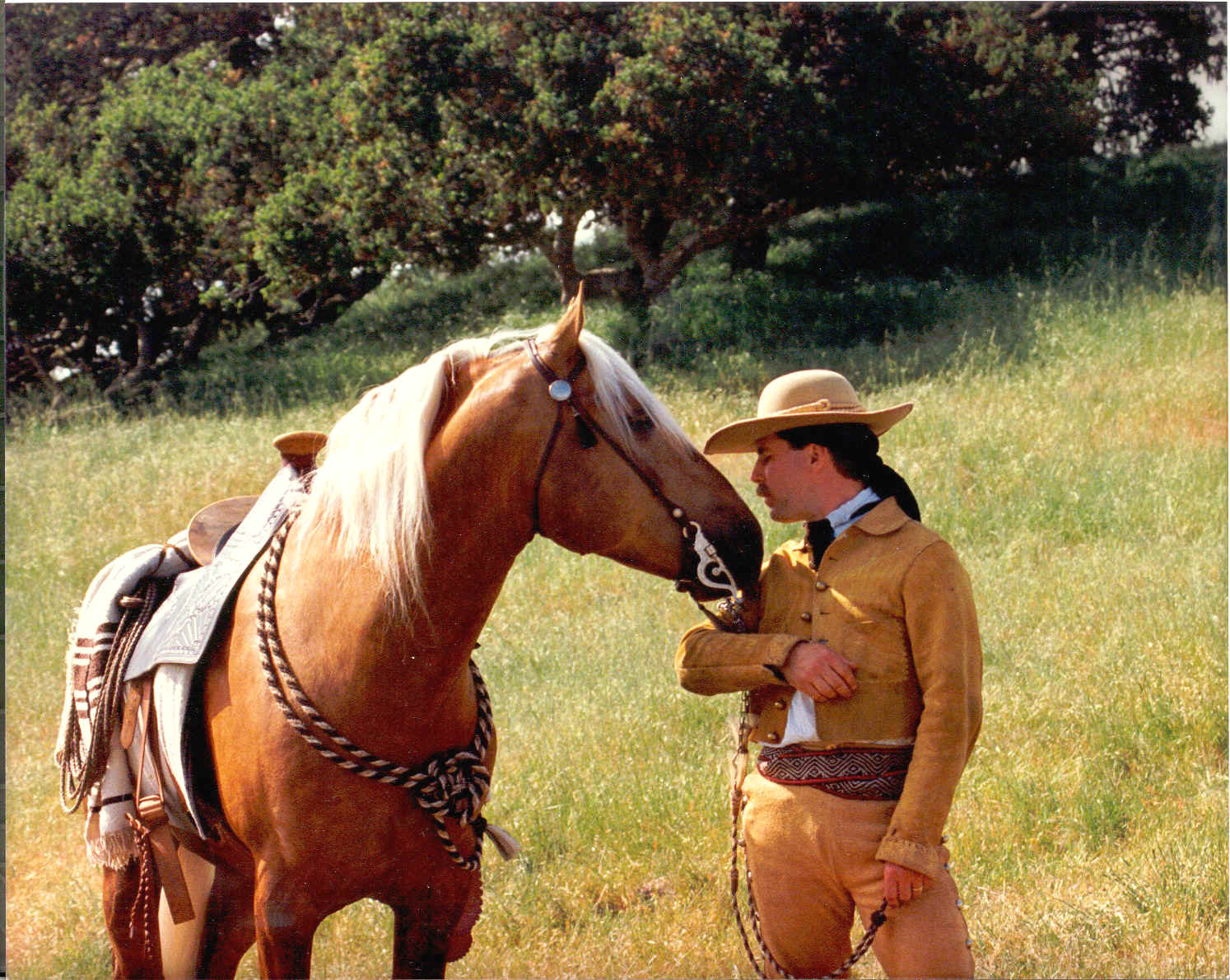

Envìo a Uds. Reconocimientos y fotos tomadas el dìa 28 del mes curso

en el Archivo General del Estado de Nuevo Leòn, en que participè con

la investigación que efectuè en la Dir. Gral. de Arch. e Hist. S.H. de

la S.D.N.: del Teniente Coronel de Caballerìa don Juan Nepomuceno Nàjera.

Comandante del Regimiento de los Lanceros de Jalisco, muerto

valerosamente en defensa de la patria combatiendo al frente de sus

Lanceros contra las tropas invasoras Norteamericanas el dìa 21 de

Septiembre de 1846 en Monterrey, N.L. Fuè el Jefe de mayor grado

de la Divisiòn de Operaciones del Norte al mando esta del General de

Brigada don Pedro de Ampudia y Grimarest.

Envìo a Uds. Reconocimientos y fotos tomadas el dìa 28 del mes curso

en el Archivo General del Estado de Nuevo Leòn, en que participè con

la investigación que efectuè en la Dir. Gral. de Arch. e Hist. S.H. de

la S.D.N.: del Teniente Coronel de Caballerìa don Juan Nepomuceno Nàjera.

Comandante del Regimiento de los Lanceros de Jalisco, muerto

valerosamente en defensa de la patria combatiendo al frente de sus

Lanceros contra las tropas invasoras Norteamericanas el dìa 21 de

Septiembre de 1846 en Monterrey, N.L. Fuè el Jefe de mayor grado

de la Divisiòn de Operaciones del Norte al mando esta del General de

Brigada don Pedro de Ampudia y Grimarest.

“La sierra de Chihuahua, soberbia, imponente, fuè

testigo. Fuerzas del Corl. Don Joaquìn Terrazas, dividida en 2 columnas: una bajo su mando y otra al de Juan Mata Ortiz; atardecer del dìa 14 de Octubre de 1880 en Tres Castillos. El feroz Victorio, valiente hasta lo increíble, verdugo del cristiano, indomable Jefe de la Apacherìa, està frente a frente de Mauricio Corredor, el noble Tarahumara, Capitàn de los voluntarios de Arisiachi; sus miradas se encuentran en actitud de reto, se acordarìa

“La sierra de Chihuahua, soberbia, imponente, fuè

testigo. Fuerzas del Corl. Don Joaquìn Terrazas, dividida en 2 columnas: una bajo su mando y otra al de Juan Mata Ortiz; atardecer del dìa 14 de Octubre de 1880 en Tres Castillos. El feroz Victorio, valiente hasta lo increíble, verdugo del cristiano, indomable Jefe de la Apacherìa, està frente a frente de Mauricio Corredor, el noble Tarahumara, Capitàn de los voluntarios de Arisiachi; sus miradas se encuentran en actitud de reto, se acordarìa

El ameritado Coronel de Caballerìa don Pedro Advìncula Valdès, falleció en San Juan de Sabinas, Coah. El dìa 13 de Agosto de 1887, a consecuencia de una hipertrofia del corazón, ocasionada por una aneurisma de la aorta descendente cuyas lesiones fueron desarrolladas por una antigua herida de arma de fuego que recibió atravezandole la caja toràxica, según informes de personas fidedignas en un combate que sostuvo el año de 1872, cerca de Lampazos, N.L. con las fuerzas levantadas al mando del Coronel Rosalìo Rubio, en defensa del Gobierno Federal legítimamente constituido y representado entonces por el Sr. Presidente don Benito Juàrez.

El ameritado Coronel de Caballerìa don Pedro Advìncula Valdès, falleció en San Juan de Sabinas, Coah. El dìa 13 de Agosto de 1887, a consecuencia de una hipertrofia del corazón, ocasionada por una aneurisma de la aorta descendente cuyas lesiones fueron desarrolladas por una antigua herida de arma de fuego que recibió atravezandole la caja toràxica, según informes de personas fidedignas en un combate que sostuvo el año de 1872, cerca de Lampazos, N.L. con las fuerzas levantadas al mando del Coronel Rosalìo Rubio, en defensa del Gobierno Federal legítimamente constituido y representado entonces por el Sr. Presidente don Benito Juàrez.

Cultural importance

Cultural importance