|

·

|

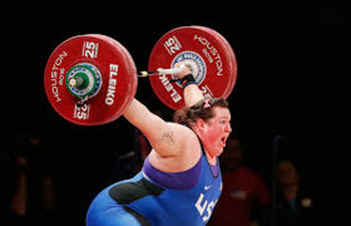

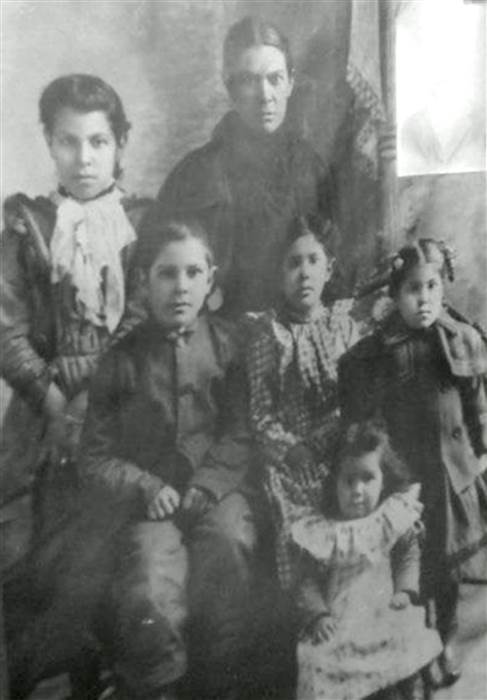

A

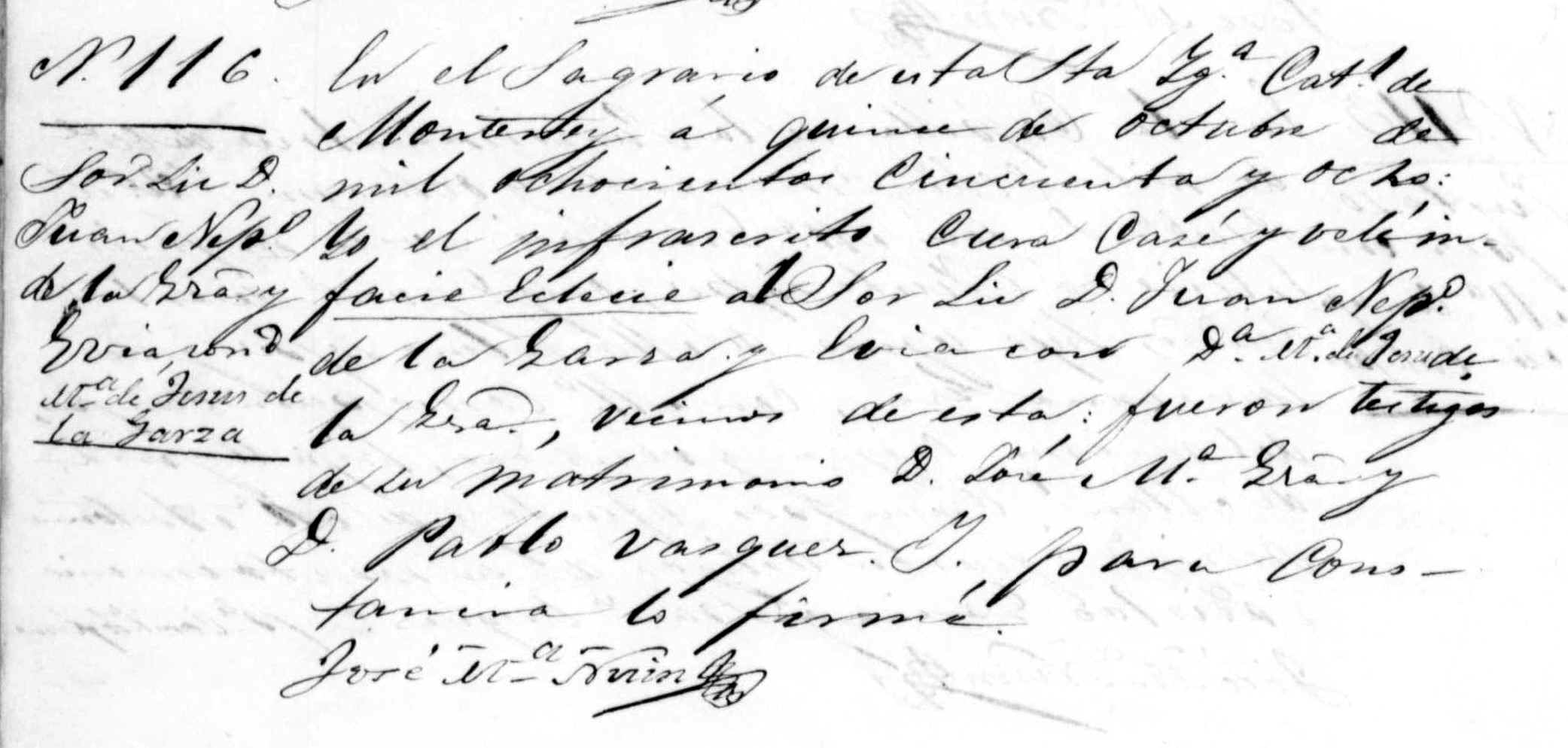

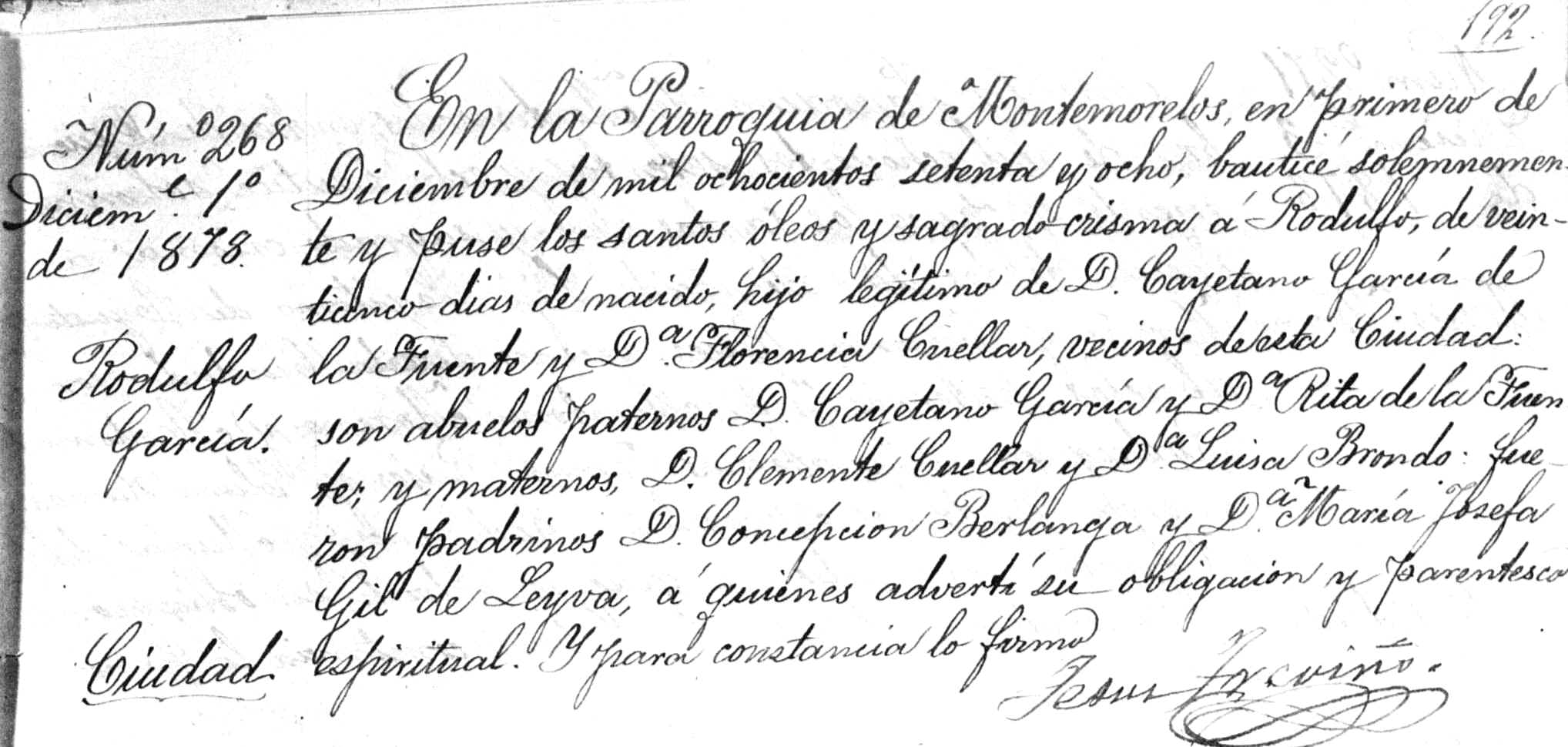

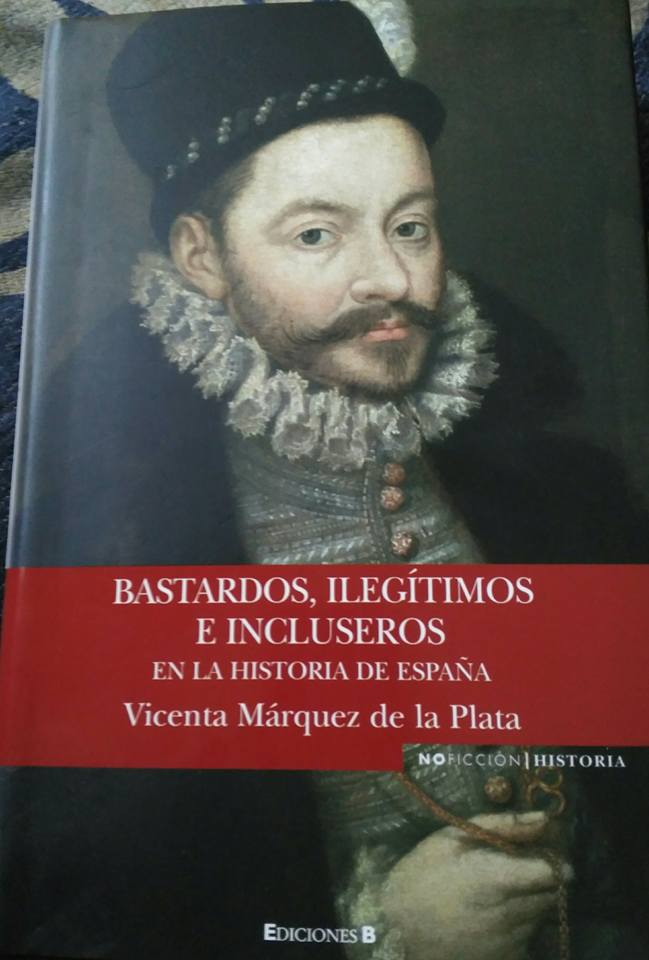

group of women who took the ranch's Americanization classes. Morales

is the cute toddler at the bottom left.

|

Decades

later, long after federal authorities deported the last of her students,

Arletta Kelly still remembered the cactus.

In

the 1920s and 1930s, Kelly had worked as an Americanization teacher in the

citrus camps of Orange County, tasked with schooling Mexican immigrants in

the art of good citizenship. During the day, she taught women how to sew

and cook American meals like casseroles and pies; at night, the Michigan

native recited basic English phrases before audiences of men so that they

could use them at work. She bounced across the colonias(worker

colonies) of North County, from La Habra to Placentia, Anaheim to

Fullerton. But Kelly eventually spent most of her time with the Mexicans

of the Bastanchury Ranch, 6,000 rolling acres of what now constitutes the

exclusive neighborhoods of northwest Fullerton—Sunny Hills, Valencia

Mesa and others—and parts of Brea and La Habra, an area that to this

day, with its winding roads, visible horse stables, dramatic valleys and

stretches of untouched California landscape, feels rustic, beautiful and

foreboding.

In

1968, Betty Schmidt with the Center for Oral and Public History (COPH) at

Cal State Fullerton interviewed Kelly about her days at the Ranch—and

that's when Kelly brought up the cactus. By then 70 years old, the maestra fondly

recalled the Bastanchury Mexicans, who had created a society of their own

far removed from the rest of Orange County. They were so grateful for

Kelly's tutorship that women frequently invited her to their ramshackle

homes for dinner and a bit of south-of-the-border hospitality. Kelly

singled out the cooking of one woman because, as she told her interviewer,

"One of the things that she served so frequently that I was fond of

was what she called 'nopalitos,' which are the little tiny shoots of the

cactus."

Schmidt

asked from where did the unnamed Mexican woman buy the nopalitos.

"There were big cactus" all around the Bastanchury territory,

Kelly said. "And then when the spring came they would come up; why,

when the shoots would come up, [the Mexican woman] would cut them off and

peel them and slice them down and cut them up in little bits."

The

rest of Kelly's interview, transcribed and available for reading at the

COPH archives, is filled with similarly pastoral anecdotes, stories about

riding a bicycle, about another Mexican woman who pronounced

"cheese" as "Jesus," and about her role in helping

orchard growers fight strikers during the 1936 Citrus War. But when

Schmidt asked about the fate of her students at the Ranch, Kelly's sharp

memory quickly became spotty.

"Well,

I think many of them went back to Mexico because work was scarcer and some

of them had accumulated a little bit of money and so I knew of quite a few

families that packed up and they drove back—in old jalopies—back to

Mexico—the ones I happen to know of," Kelly said. "Now, others

may have gone by some other method, I don't know."

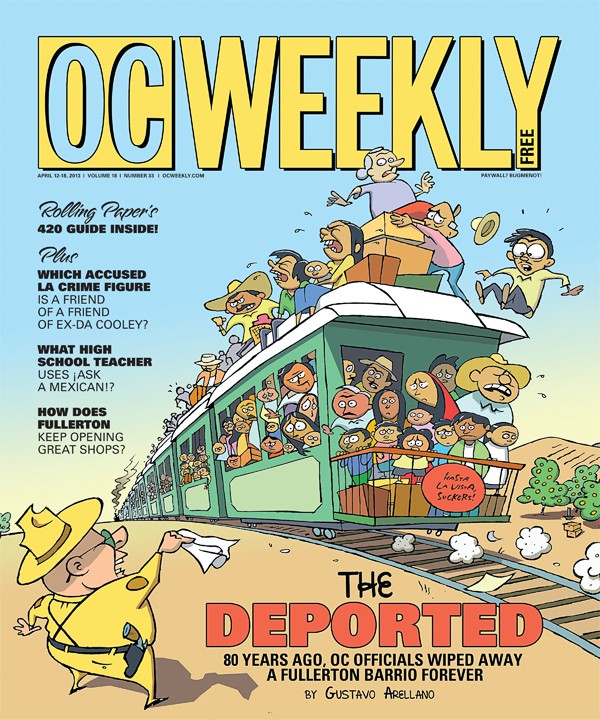

In

fact, the Mexicans who lived on the Bastanchury Ranch in the early 1930s

were subject to one of the largest mass deportations in Orange County

history, with hundreds of them in late March of 1933—single men and

families, Mexican nationals and American citizens—thrown onto trains

bound for Mexico, carrying with them only the clothes on their backs and

whatever belongings they could lug along. Almost overnight, a vibrant

community vanished, the homes of former residents demolished, its memory

bulldozed into wealthy neighborhoods, the few surviving scraps locked in

university archives or in the recollections of those few families that

escaped exile.

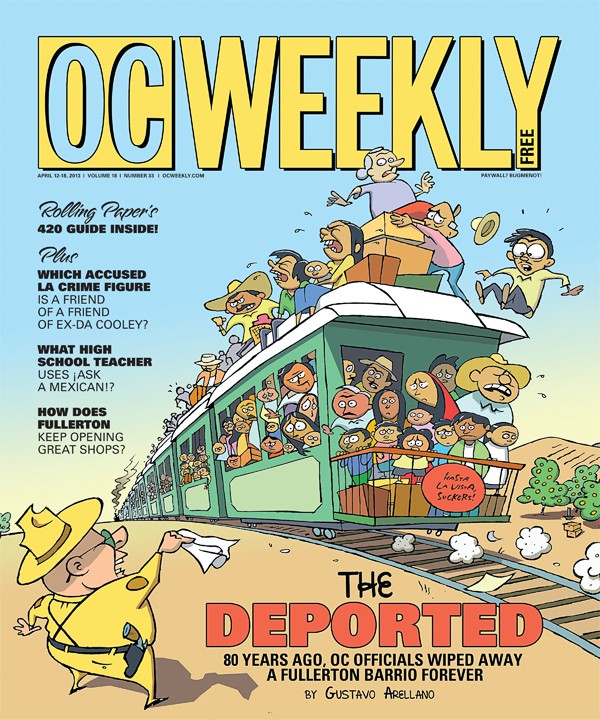

Eighty

years ago this spring, officials deported hundreds of legal residents

whose only crime was being Mexican during the Great Depression—and

Orange County has tried to forget ever since.

The

Bastanchury family is familiar to generations of Southern California

residents and scholars alike, and not just because of their namesake road,

which unspools through the hills of Fullerton, Brea, Placentia and Yorba

Linda. The Basque clan were one of Orange County's first national

celebrities, a dynasty whose patriarch, Domingo, arrived at what's now

Fullerton in the 1860s and eventually acquired about 10,000 acres of

desolate terrain: for decades, his house was just one of two between

Anaheim and Los Angeles. Originally using his holdings as grazing lands

for sheep, Domingo's four sons eventually turned the Ranch into an

agriculture and livestock powerhouse: 1,500 acres devoted to black-eyed

peas, 500 acres for lima beans; hundreds of acres of walnut orchards and

fields that, by 1928, sold more than 50 percent of California's tomatoes;

10 acres of Berkshire hog pens; and canneries and two packing houses that

boxed the Ranch's riches for sale to the rest of America. Oil money came

in the form of a legal settlement, and some of the water drawn from

artesian wells for irrigation was sold publicly as Bastanchury Water, a

brand that existed for decades. The estate was so sprawling that the

Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe and Union Pacific railroads built spurs near

the packing houses, the easier to pick up the bounty, while the Pacific

Electric Railway kept two stations within Ranch limits. Managers had to

cut up the Ranch into sections with their own supervisors, just to handle

everything properly.

But

the crown jewel of the Bastanchurys was their 3,000-acre citrus grove,

rows of Valencia orange and lemon trees that went up and down the Ranch,

held in place by terrace farming. On the family's stationery and on the

labels for their orange crates, marketed under the Model, Basque, Daily,

Popular and Golden Ram brands, read the slogan "The World's Largest

Orange and Lemon Orchard," a claim no one bothered to dispute.

Domingo's

sons were fiercely proud of their accomplishments and never shied away

from boasting about what they had willed up from what many considered

remote badlands. "Some of my ideas were discountenanced by scientific

men, by farm bureau men," Gaston Bastanchury told the California Citrograph,

the bible of the Golden State's citrus industry, in 1923. He was the

public face of the family, a man who frequently made the society pages for

his many trips abroad, a tycoon so rich that he once offered heavyweight

champion Jack Dempsey an $800,000 purse if the Manassa Mauler would fight

on the Ranch, in a custom-built arena Gaston promised would seat 135,000

people. "I felt that I knew what we could do and kept on. But the

fact remains that these old brown hills—and you can still see hundreds

of acres in that same state around us—have produced trees and those

trees are beginning to return something on the investment of labor and

money which have been put into them."

Life

was fabulous on the Ranch—it became the center of Basque life in

Southern California, featuring weekend-long parties filled with

traditional lunches and dinners. There was even a handball court so that

nostalgic men could play the jai alai of their youth. But to create their

dreamland, the Bastanchurys needed cheap labor—first, Native Americans,

then fellow Basques and a smattering of Japanese. By the 1920s, though,

cheap labor in Southern California agriculture meant Mexican workers, and

the Bastanchurys began recruiting across the Southwest and abroad, uniting

with fellow Orange County orchard owners to lobby Congress for relaxed

immigration laws, arguing only Mexicans could properly work with oranges.

"Our

experience shows us that the white man does not like the tedious routine

work of picking and will promptly leave this for any other job available,

even at smaller wages," wrote J. A. Prizer, manager of the Placentia

Orange Growers Association, in a prepared statement given to Congress in

1928. At that same hearing, Prizer revealed that county growers used the

Bastanchurys' worker rolls to determine how many Mexicans they needed to

run a successful operation. "The Mexican, by nature, seems to be

peculiarly adapted to this class of work. He is patient, and apparently

enjoys the work itself."

And

so the Bastanchurys brought in hundreds of Mexicans. A contemporary of the

dynasty derided the Ranch as "their own private kingdom in the

Fullerton hills," isolated from the rest of civilization, and it

wasn't far from the truth: while grower-sponsored worker camps sprang up

across Orange County's citrus belt, the Bastanchurys' orange pickers lived

like serfs.

"[The

Bastanchurys] had the Old World feudalistic attitude toward their farm

hand," wrote Druzilla Mackey, an Americanization teacher in Orange

County alongside Arleta Kelly, in a 1949 history of education in

Fullerton. She had no problem with the workers, describing them as

"always the poorest of our Mexicans, the most friendly and also the

most idealistic." But she openly despised the Bastanchurys, writing

"they felt generous in allowing these squatters to establish homes on

their ranch and could not comprehend its danger to the health and morality

of the community as a whole."

Mackey

described abodes constructed from sheet iron, discarded fence posts, sign

boards, even rusted bed springs—whatever detritus Mexicans could find in

the Ranch's trash dump; Kelly remembered one built of "cartons and

wood and pieces of tin." Some houses were half-wood, half-canvas. Few

had running water; nearly all had outside, shared toilets. Rains turned

everything into a swamp; despite the abundance of artesian water, families

had to draw their own from irrigation ditches and carry it via buckets to

their homes. Once a week, a grocery wagon arrived with fresh produce and

meat—a necessity, since almost no one had refrigeration because there

was little electricity. Some homes had dirt floors, some were just tents.

Elsie Carlson, who taught the Ranch's Mexican children, put it thusly:

"I felt like a missionary."

The

conditions endured by the Bastanchury Mexicans became something of a

county scandal; a newspaper exposé, lost to history but cited by Kelly in

her COPH oral history, mentioned the "exceedingly primitive and

poverty stricken" condition of the camp, which upset the Bastanchurys

and their management. But after organizing by the Americanization teachers

and the Rev. Graham C. Hunter of the First Presbyterian Church of

Fullerton, the Ranch finally relented and built homes for workers with

potable water in 1927, along with a wooden classroom for first-, second-,

and third-graders—tellingly, the Basque and white children on the Ranch

were bussed to the "white" schools in the Fullerton flatlands,

while the Mexican children on the Ranch had to trudge at least a half mile

to school on dirt roads through orchards.

A

community grew. The 1920 census showed only a few Mexicans living on the

Ranch; by the 1930 census, the official count was 411. It had grown so

much that the U.S. Census Bureau gave the Bastanchurys their own

designated tract, split into six colonias: Tia Juana,

Mexicali, Escondido, Coyote, Santa Fe and San Quintín, which some

ominously called El Hoyo—The Hole. Tia Juana was the largest, then

Mexicali, and they were around what's now Laguna Lake Park in Fullerton;

the rest gravitated near what's now St. Jude Hospital. Stand-alone shacks

remained dotted throughout the Ranch.

"I

think they were very happy people, really, they lived a very simple life,

but it was probably somewhat better than the life they lived in

Mexico," Kelly said, and the Mexicans made do with what they had.

Though the houses were downtrodden, they were well kept, with gardens of

flowers and vegetables prettying the environment. Mothers sent their

children off to school scrubbed clean and dressed in their Sunday best.

During the major Mexican holidays—Mexican Independence Day, Cinco de

Mayo and Dia de los Muertos—the colonias held their own private celebrations or

traveled together to Placentia and Los Angeles to partake in bigger ones.

A monthly dance was held at the schoolhouse, and the Americanization

teachers frequently presented their Mexican pupils to the Fullerton

population at large as proof of their good work, affairs that earned

approving write-ups in the Fullerton News Tribune and theSanta Ana Register. No one was an illegal immigrant; all

the Bastanchury Mexicans were either American citizens or sponsored by

their hosts, with most originating from Tepic, Jalisco.

This

bucolic life couldn't last. In October 1931, at the height of the Great

Depression, the Bastanchurys shocked Orange County by announcing they had

debts of $2 million and were placing their beloved Ranch into a

receivership. The celebrated citrus grove wasn't producing; it turned out

that the soil on the Ranch wasn't conducive to large-scale, long-term

growing, just as the old-timers had tried to tell the Bastanchurys.

But

something more nefarious had infested the Ranch as well. In just three

years, Orange County politicians had gone from begging Congress for more

Mexican labor to demanding that those workers give up their jobs, homes

and lives to whites and return to Mexico. By 1931, federal agents were

raiding barrios and colonias across Southern California, rounding up

legal residents and American citizens of Mexican descent alike, and

deporting them to Mexico; upon arriving, the Mexicans were forced to give

up their legal papers allowing entry back into the States. Taking a kinder

approach, church, civic and business groups asked Mexicans to leave,

vowing to pay their train fare. Even the Mexican Consulate, not wishing to

anger their American neighbors, organized return trips back, with promises

of jobs that somehow never materialized.

Without

the family's patronage, the Bastanchury Mexicans were threatened. In the

fall of 1932, the Mexican Consulate helped to organize a meeting in

Fullerton to figure out how immigrants could stave off repatriation. The

government's deportation campaigns had begun in Orange County, organized

by the local Department of Welfare. The consulate's Orange County

representative, Santa Ana resident Lucas Lucio, accompanied deported

Mexicans from the Santa Ana train station to Union Station in Los Angeles,

where he would then join them on a Southern Pacific train to El Paso to

ensure they weren't further abused. Even 45 years later, in an interview

with a professor, the experience made Lucio shudder.

"At

the station in Santa Ana, hundreds of Mexicans came and there was quite a

lot of crying," he said. "The men were pensive and the majority

of the children and mothers were crying." Lucio told the story of how

on one trip, when the train didn't stop in El Paso but rather proceeded

into Juarez, there was "a terrible cry... many did not want to cross

the border ... a disaster, because the majority of the families were

separated. There was no way for anyone to try to leave the train or run or

complete their desire to return to the United States."

In

February of 1933, the Bastanchurys' empire was auctioned from the steps of

the Orange County Courthouse and put under new management; within five

days, a hundred unemployed white men swarmed the Ranch, confident white

ownership would give them a job. The era of the Bastanchury Mexicans was

about to end.

Sometime

that spring, new management and a consortium of white business, political

and civic leaders went to the Ranch's schoolhouse and told the Mexicans

they had to leave. "The Americanization centers in which these people

had been taught how to buy homes and make themselves a part of the

American community," Mackey wrote 18 years later, "were now used

for calling together assemblages in which county welfare workers explained

to bewildered audiences that their small jobs would now be taken over by

the white men, that they were no longer needed nor wanted in these United

States." As a last-ditch effort, she paraded her Americanization

students in front of a men's civic group as she always had, desperately

trying to show that the Bastanchury Mexicans were worthy of staying. But

it didn't work.

"And

so," she concluded, "one morning we saw nine train-loads of our

dear friends roll away back to the windowless, dirt-floored homes we had

taught them to despise."

|

Despite

an ominous message that warns us away, I applied and was granted

permission to finally travel to my other home in Mexico.

Despite

an ominous message that warns us away, I applied and was granted

permission to finally travel to my other home in Mexico.

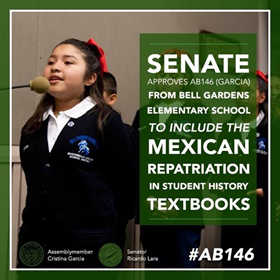

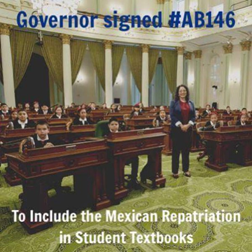

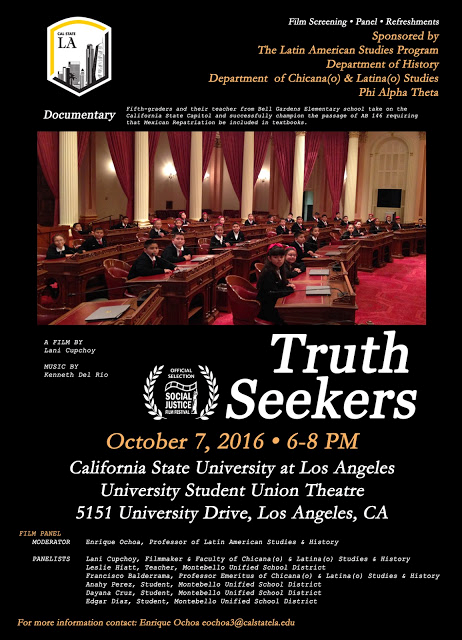

California

Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill in 2015 that instructs schools

and

California

Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill in 2015 that instructs schools

and

2.

2.

I

am writing this letter in an urgent request for aid in the

conservation of this unique genetic resource, this "equine time

capsule" on the brink of extinction. Our horses were DNA tested

in July by Dr. Gus Cothran and the results were AMAZING, (results

letter enclosed). For over twenty-six years, the Heritage Discover

Center and Rancho Del Sueno have conserved and cared for these special

horses. But

I

am writing this letter in an urgent request for aid in the

conservation of this unique genetic resource, this "equine time

capsule" on the brink of extinction. Our horses were DNA tested

in July by Dr. Gus Cothran and the results were AMAZING, (results

letter enclosed). For over twenty-six years, the Heritage Discover

Center and Rancho Del Sueno have conserved and cared for these special

horses. But

I hope you don’t mind that I jumped into your

remembrance stream to let you know that Sanjuanita was

very special person and much a part of my life, in my

formative years. It seems almost like an embryonic state

long ago, and yet I remember it like yesterday. I loved

her then, and I wish we had been given more time to know

each other as older women, but it was not to be. I

rejoice in the early days and the few hours we had in

June. I am sorry for losing a mature friendship that

could have been.

I hope you don’t mind that I jumped into your

remembrance stream to let you know that Sanjuanita was

very special person and much a part of my life, in my

formative years. It seems almost like an embryonic state

long ago, and yet I remember it like yesterday. I loved

her then, and I wish we had been given more time to know

each other as older women, but it was not to be. I

rejoice in the early days and the few hours we had in

June. I am sorry for losing a mature friendship that

could have been.

On

January 9, 2008, 20 year old Sgt. Zachary McBride lost his

life after he entered a home, booby trapped with explosives

in Sinsil, Iraq with 5 of his comrades. Sgt. McBride who had

chosen to defray college life and the promise of

scholarships, and instead volunteer for the ARMY. Like so

many young volunteers, Zachary was in school when he watched

the events of 9/11 and decided, on that day, that he would

join the Army. His death changed many worlds that day,

one of which was the founder of Resurrecting Lives, Dr.

Chrisanne Gordon. On that day, she dedicated herself

to making a change for our returning veterans. To Read more

about Sgt. McBride, please

On

January 9, 2008, 20 year old Sgt. Zachary McBride lost his

life after he entered a home, booby trapped with explosives

in Sinsil, Iraq with 5 of his comrades. Sgt. McBride who had

chosen to defray college life and the promise of

scholarships, and instead volunteer for the ARMY. Like so

many young volunteers, Zachary was in school when he watched

the events of 9/11 and decided, on that day, that he would

join the Army. His death changed many worlds that day,

one of which was the founder of Resurrecting Lives, Dr.

Chrisanne Gordon. On that day, she dedicated herself

to making a change for our returning veterans. To Read more

about Sgt. McBride, please  On

July 19, 2010, 27 year old Staff Sgt. Brian F. Piercy, 82nd

Airborne Division, died in Arghandab River Valley,

Afghanistan, of injuries sustained when insurgents attacked

his unit using an improvised explosive device. “He

believed in the values of the Army and in the mission of

what he was doing in Afghanistan.”— David Piercy,

brother as stated in the newspaper Fresno Bee. Staff Sgt.

Piercy, always a leader and a patriot, is one of eight young

heroes who have perished in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan

from his high school in Clovis, California. His

brother, Kevin, also served with him at Fort Bragg. Brian is

the inspiration for the Fort Bragg employment program that

will allow military members to obtain a job and an education

prior to military separation. To read more about

Staff Sgt. Piercy please

On

July 19, 2010, 27 year old Staff Sgt. Brian F. Piercy, 82nd

Airborne Division, died in Arghandab River Valley,

Afghanistan, of injuries sustained when insurgents attacked

his unit using an improvised explosive device. “He

believed in the values of the Army and in the mission of

what he was doing in Afghanistan.”— David Piercy,

brother as stated in the newspaper Fresno Bee. Staff Sgt.

Piercy, always a leader and a patriot, is one of eight young

heroes who have perished in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan

from his high school in Clovis, California. His

brother, Kevin, also served with him at Fort Bragg. Brian is

the inspiration for the Fort Bragg employment program that

will allow military members to obtain a job and an education

prior to military separation. To read more about

Staff Sgt. Piercy please

The

reunion was founded to celebrate, honor and pay tribute

to those who made this city their home in the search for

a better life for themselves and their children. Every

one enjoyed the day sharing stories, memories, photos

and precious mementos of the past. Great grandparents,

grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles, cousins and

friends names were in the air along with the stories

that brought us all together to fuse a community that is

dearly treasured and celebrated as the Olive Street

Barrio.

The

reunion was founded to celebrate, honor and pay tribute

to those who made this city their home in the search for

a better life for themselves and their children. Every

one enjoyed the day sharing stories, memories, photos

and precious mementos of the past. Great grandparents,

grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles, cousins and

friends names were in the air along with the stories

that brought us all together to fuse a community that is

dearly treasured and celebrated as the Olive Street

Barrio.

Museum

of the San Ramon Valley

Museum

of the San Ramon Valley

Voces Oral History Project

Voces Oral History Project

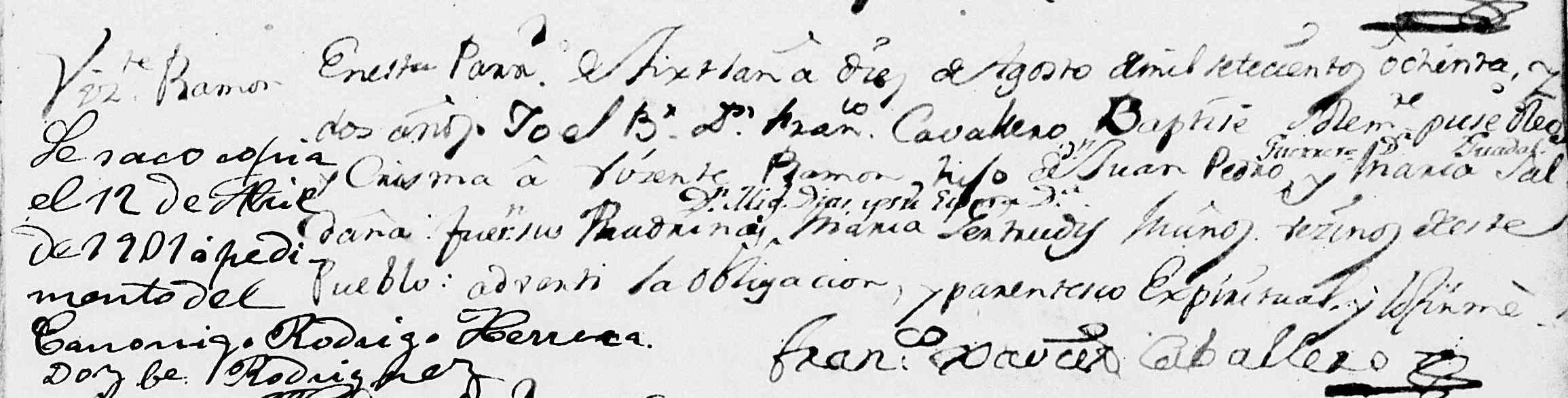

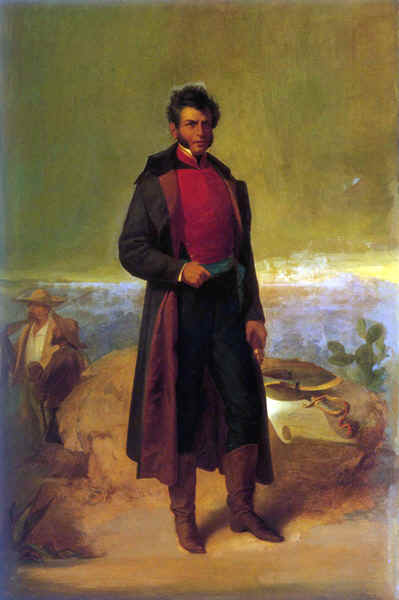

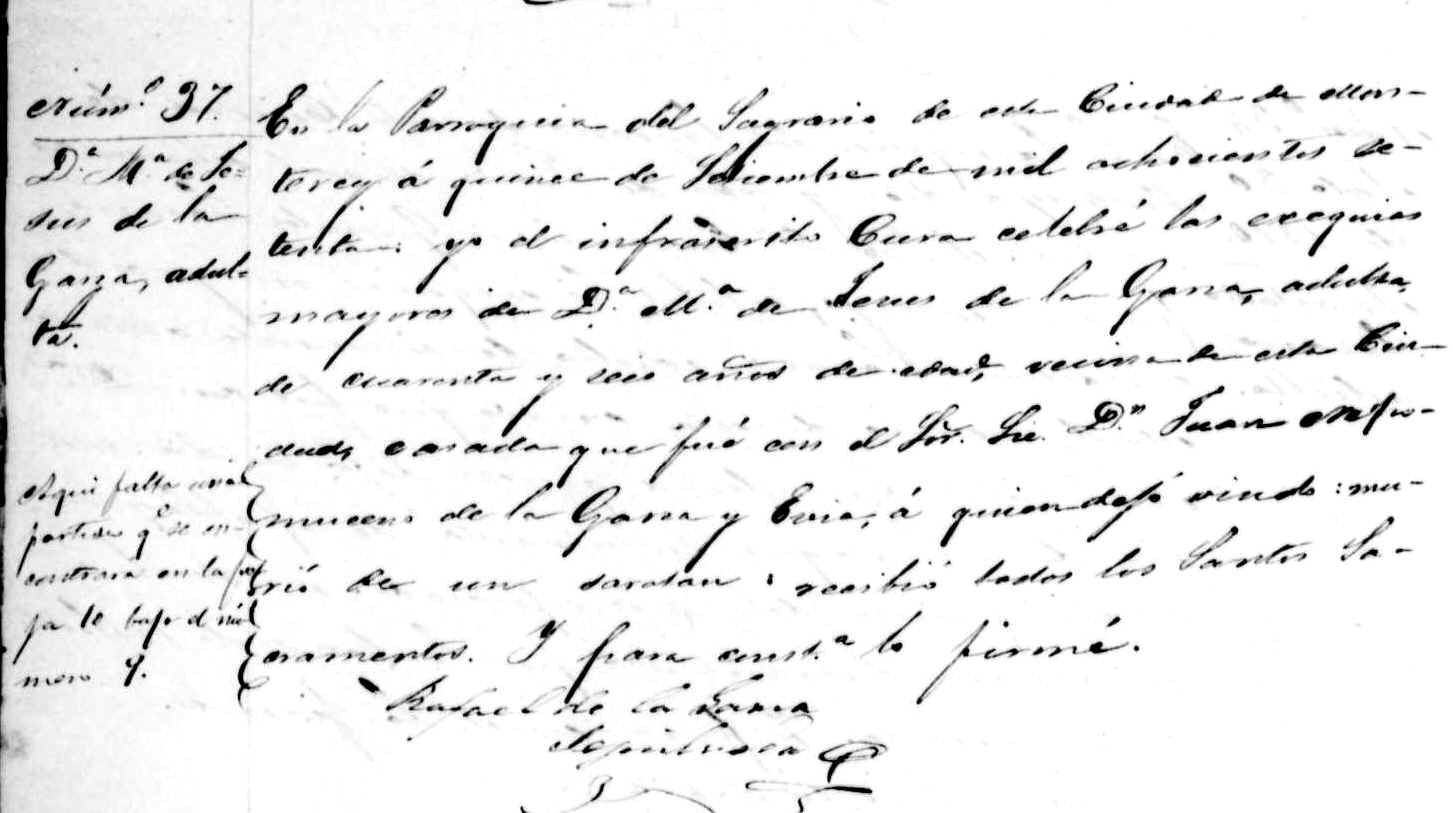

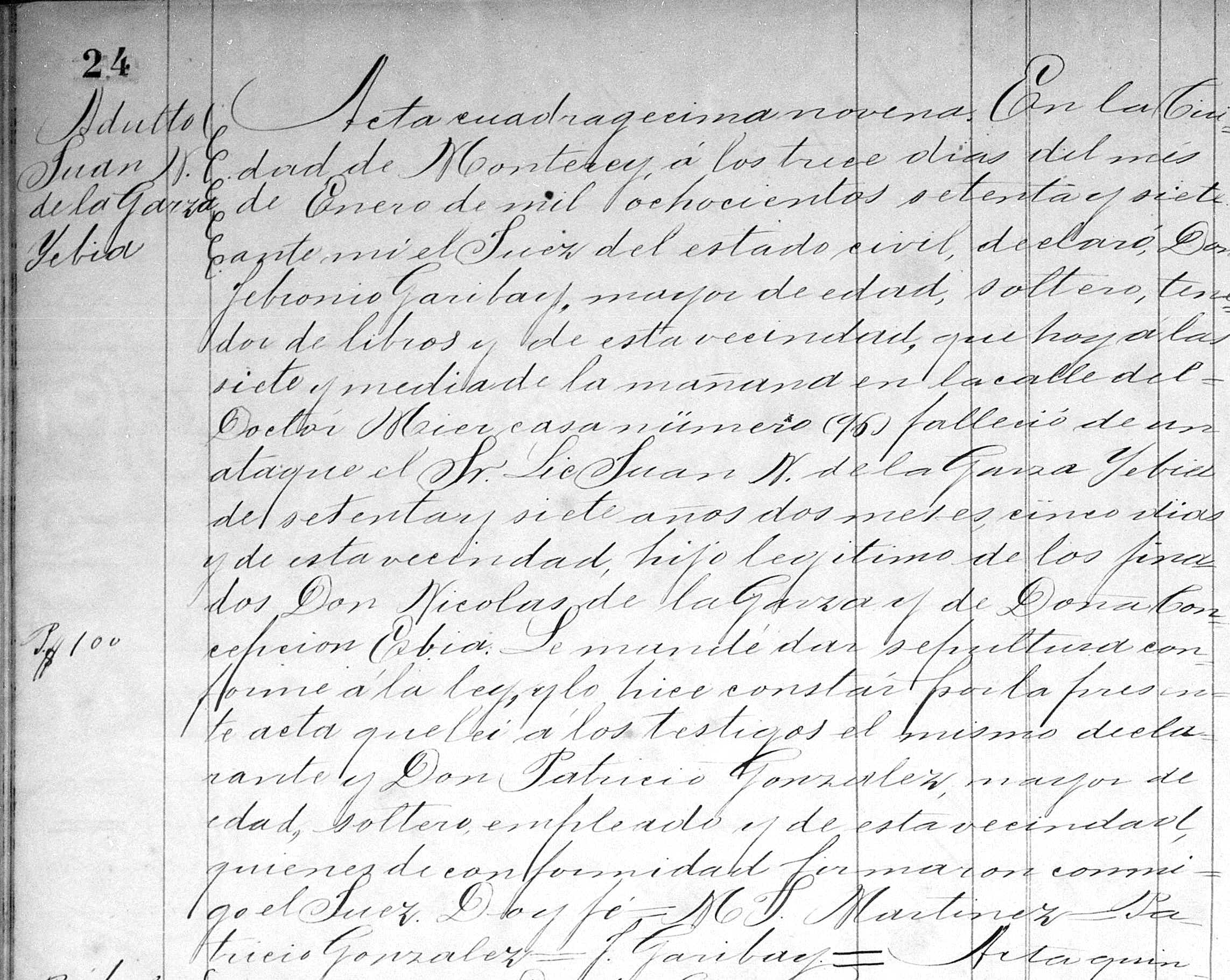

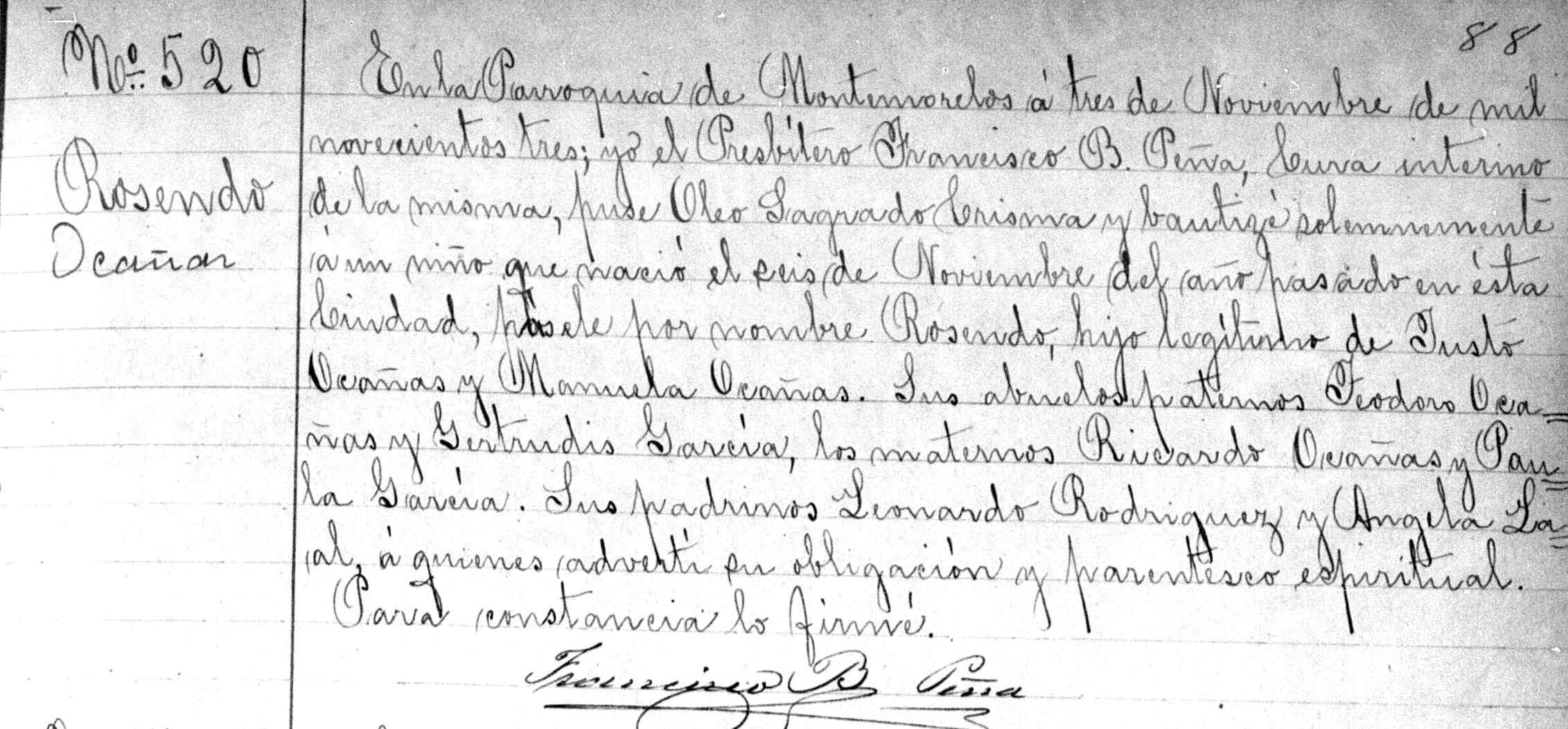

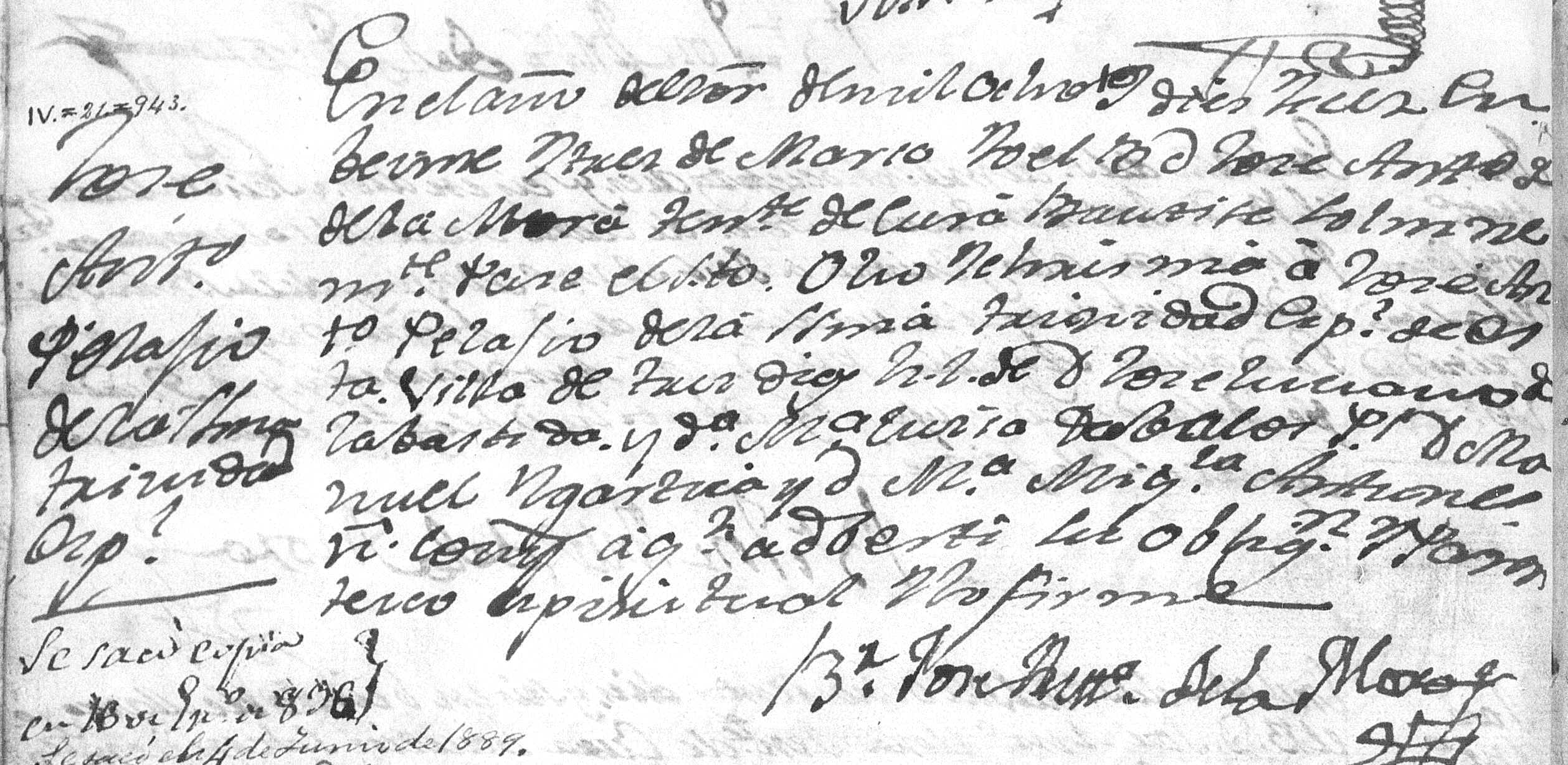

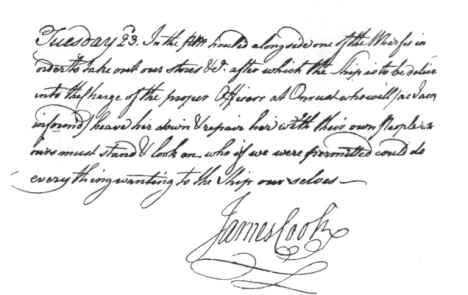

Envìo

a Uds. la imagen del registro del bautismo del General Insurgente Don

Vicente Guerrero Saldaña. Benemèrito de la Patria.

Envìo

a Uds. la imagen del registro del bautismo del General Insurgente Don

Vicente Guerrero Saldaña. Benemèrito de la Patria.