|

- Extracted from "Records of California

Men in the War of the Rebellion, 1861 To 1867." 1890. pp

304-306.

- Transcribed by Sandy Neder.

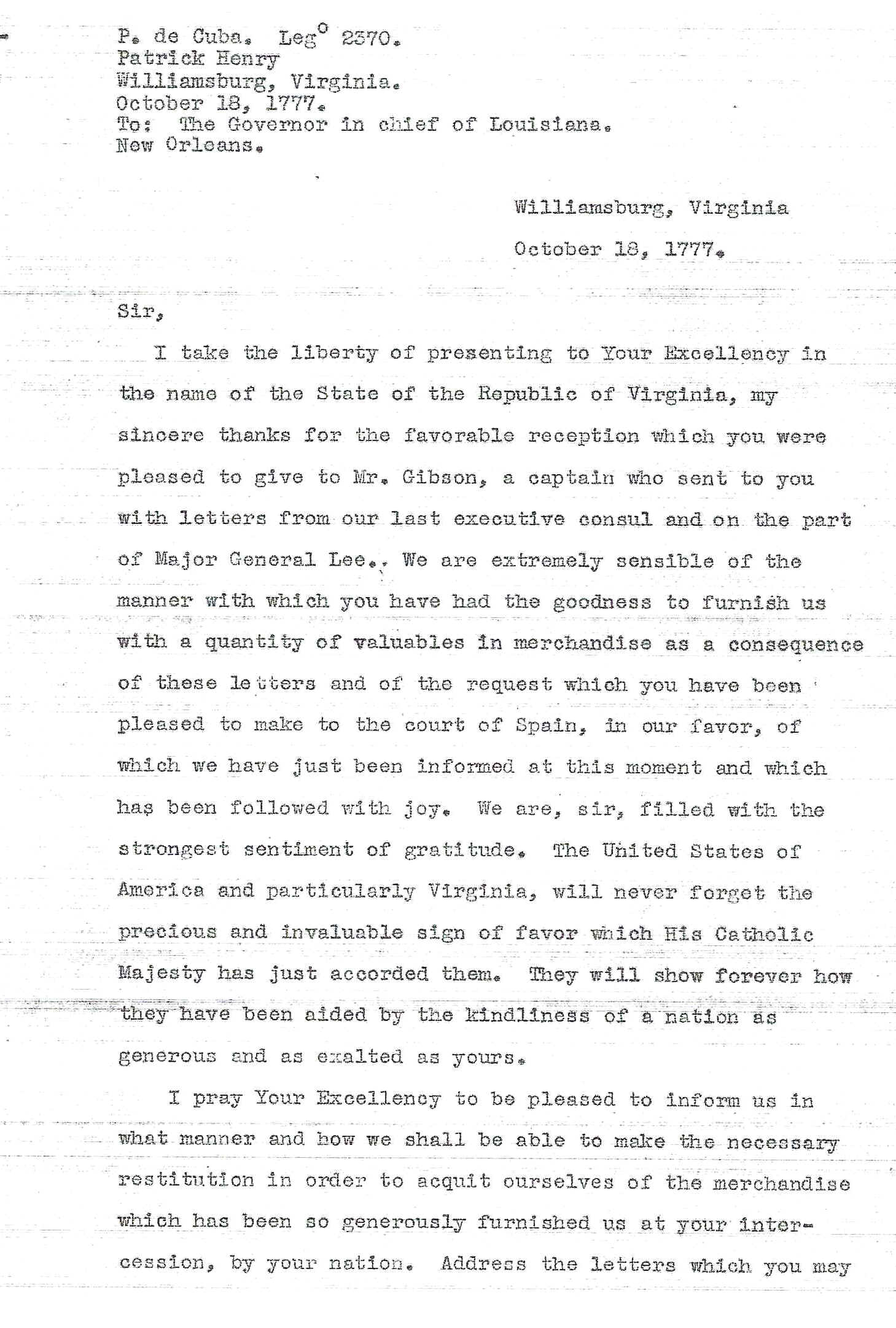

The extraordinary horsemanship displayed by the native

Californians led to the belief that a battalion of cavalry,

composed entirely of such, would render excellent service in

Arizona. Accordingly a telegram, a copy of which is here inserted,

together with the reply, was sent to the War Department.

-

-

[Telegram.]

San Francisco, December 19, 1862.

To Adjutant-General L. Thomas:

I request authority to raise four

companies of native cavalry in the Los Angeles District,

to be commanded by a patriotic gentleman, Don Andreas

Pico.

G. WRIGHT

Brigadier-General

|

[Telegram.]

War Department, Adjustant-General's Office,

Washington, January 20, 1863.

To General Wright, San Francisco, Cal.:

Secretary of War gives authority

to raise four companies native cavalry in Los Angeles

District.

- Thomas M. Vincent,

- Brigadier-General

- Assistant Adjutant-General

|

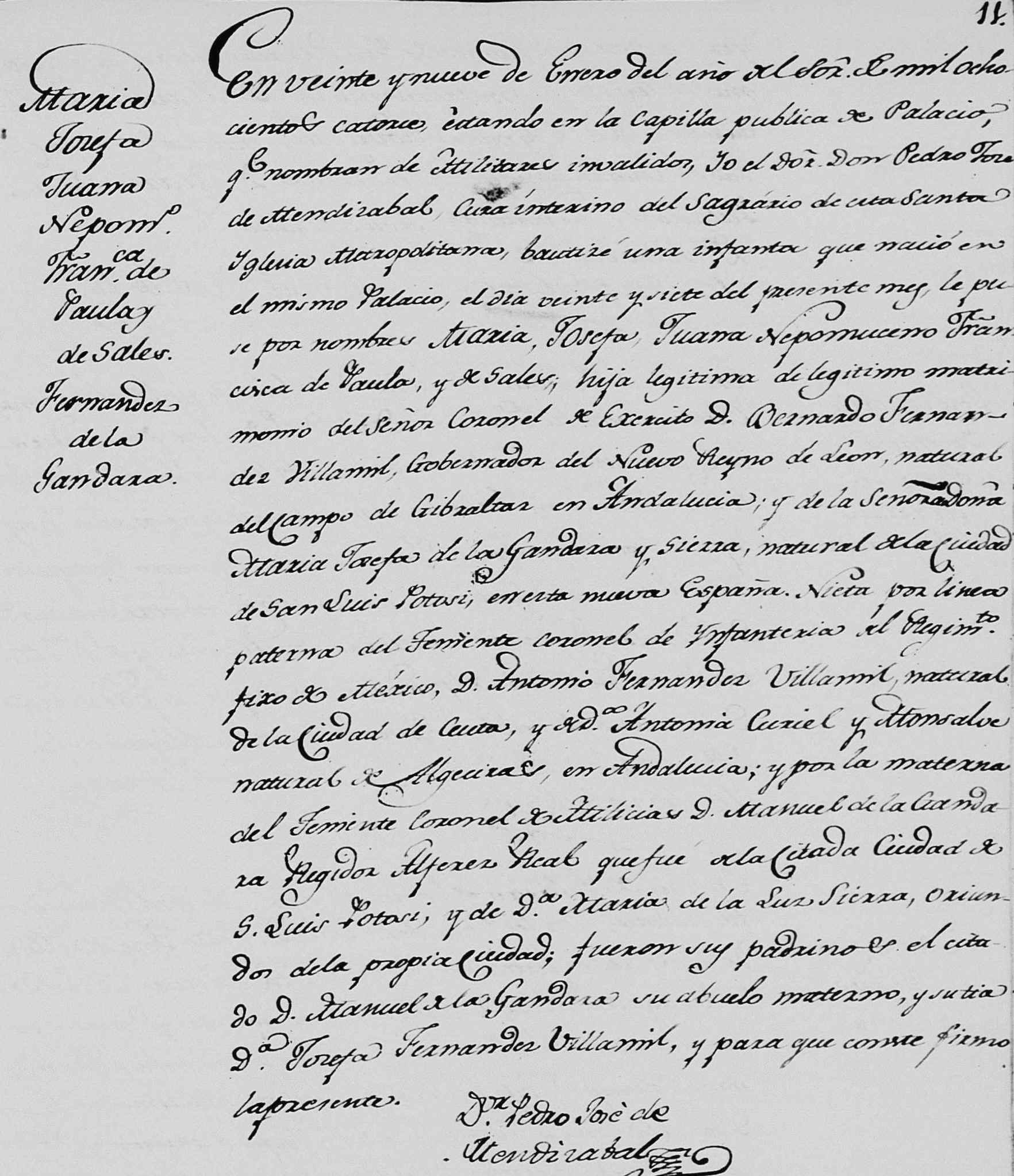

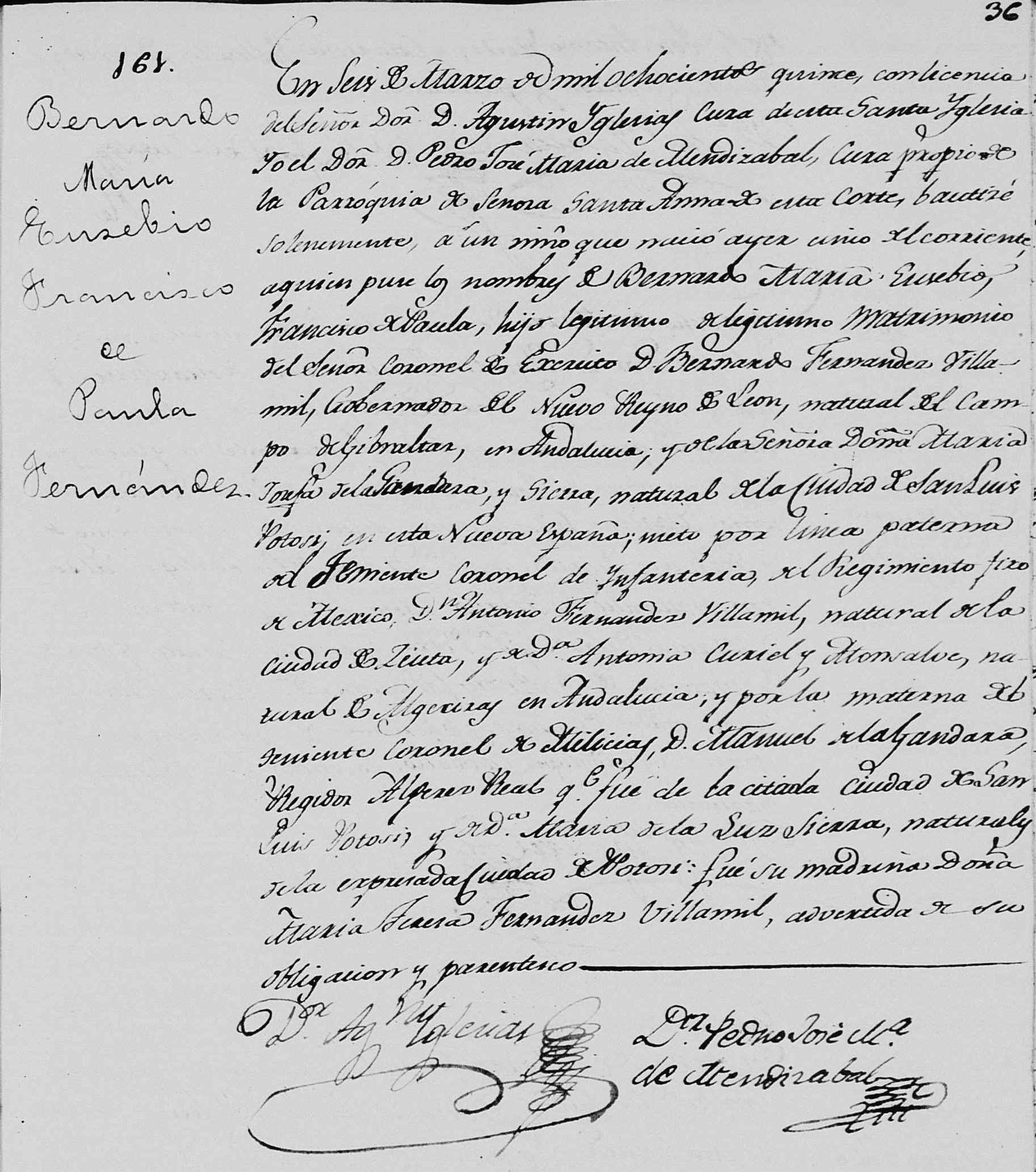

- A favorable response having been received,

the officers were appointed and the work of recruiting the

battalion commenced. Don Andreas Pico, of Los Angeles, then

Brigadier-General of the First Brigade of California militia, was

commissioned Major of the battalion. He, however, declined the

commission, on the ground of sickness and his inability to ride on

horseback.

-

- General Pico having declined, Salvador

Vallejo was commissioned Major of the battalion. He was not

mustered as such, however, until August 13, 1864. He resigned in

February, 1865, and was succeeded by John C. Cremony, who had been

a Captain in the Second California Cavalry, and, with his company,

constituted part of the 'California Column" during its march

to, and service in, New Mexico.

-

- Considerable delay was experienced in raising

men for this battalion. Recruiting commenced in February, 1863,

but the first company was not filled up and mustered until

September seventh, same year. The other companies were not

mustered in until the spring and summer of 1864.

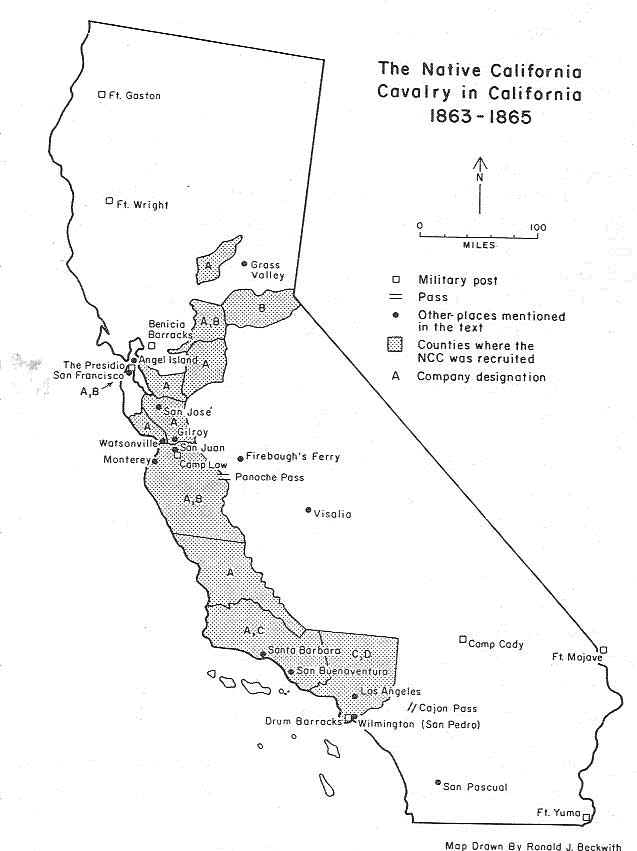

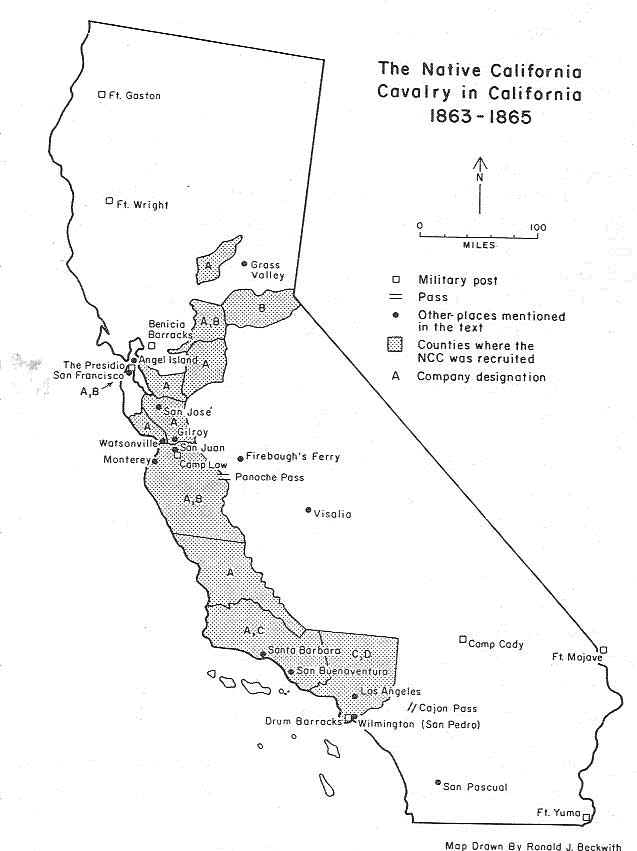

The battalion was stationed in various places in California, as

shown by the table published herewith. During the summer of 1865,

it was taken by Major Cremony to Arizona and stationed in the

southern part of that territory, until early in 1866, when it was

returned to California to be mustered out. The table on page 7

will give the dates of mustered in and muster out of the

companies. Companies A, B, and D were mustered out at Drum

Barracks; Company C was mustered out at Presidio, San Francisco.

-

- The records of this battalion are very

incomplete, and for that reason it is impossible to give a full

account of the service rendered by it. There seems to have been an

unusually large number of desertions from it. From one company

there were more than fifty; from another, about eighty.

The following is the correspondence and remarks on muster rolls

found relating to this battalion:

-

-

-

-

General

Headquarters, State of California

Adjutant-General's Office, Sacramento, June 2, 1864.

General: Colonel Curtis' letter has been read by me,

and in reply to your inquiry as to whether the

Governor has authorized Don Antonio de la Guerra to

raise a company, I have to state that the Governor did

not specially authorize him to raise a company, but

that he, on yesterday, concluded to accept his company

(known as the Santa Barbara Company), and has directed

commissions to issue, which has accordingly been done

and forwarded to Colonel Drum to-day, for the

following officers: Captain, Antonio M. de la Guerra;

First Lieutenant, Santiago de la Guerra; Second

Lieutenant, Porfino Jimeno.

The recommendation for the Fourth Infantry, California

Volunteers, I have duly forwarded to his Excellency

the Governor.

Respectfully, your obedient servant,

Geo. S. Evans

Adjutant-General, State of California.

George Wright, Brigadier-General U.S. Army, Commanding

Department of Pacific

|

-

-

State of

California, Executive Department

Sacramento, March 27, 1865

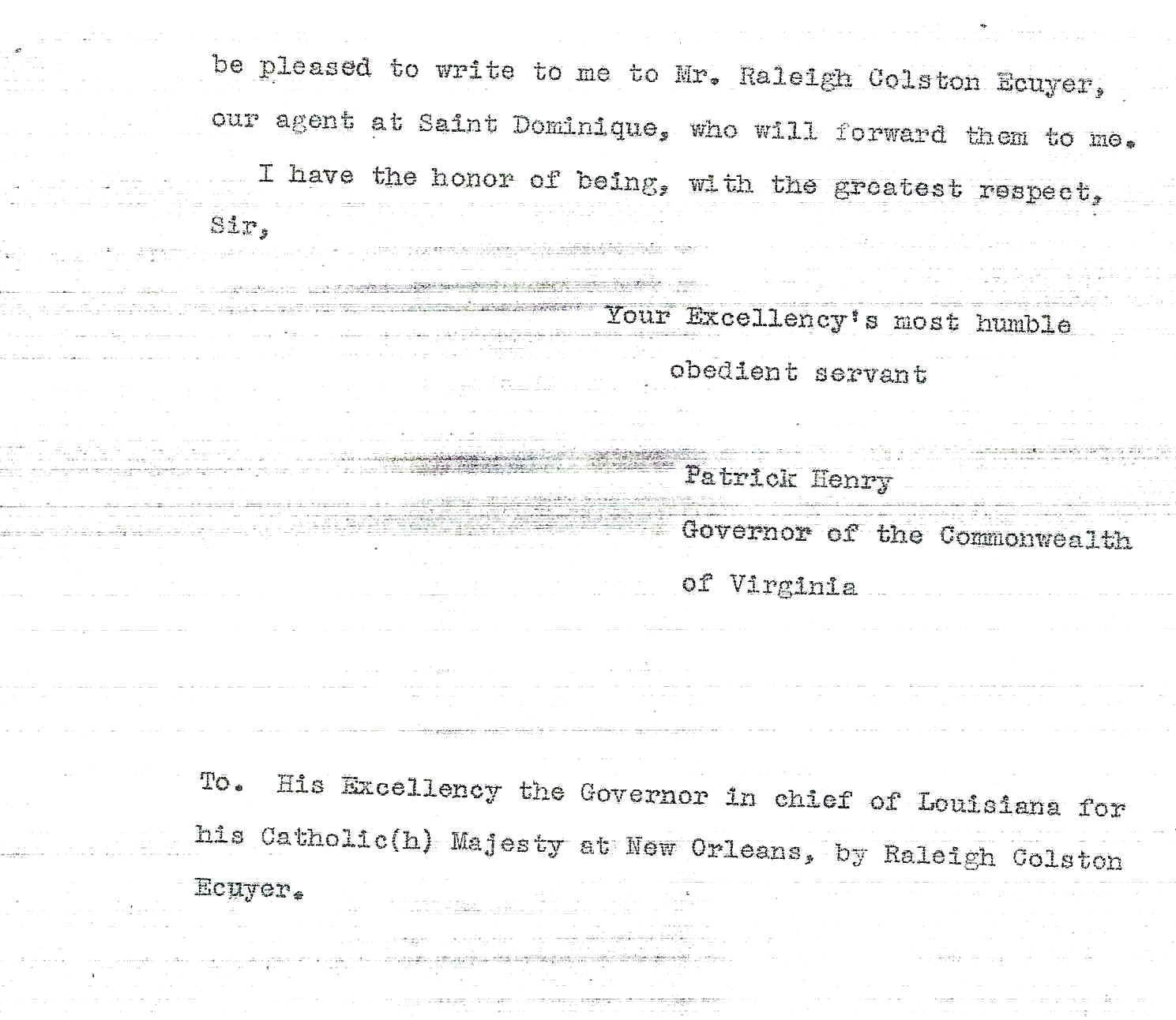

Colonel: I enclose a memorandum of the officers

already commissioned for the native battalion, as

appears from the books of the Adjutant-General.

I have the General's recommendation for Mr. Leese and

some other men (I think) for a commission in this

battalion.

Mr. Leese was commissioned by me as Adjutant, but

could not be mustered in.

From this date it appears that there are no vacancies

to fill; and even one or more of the Second

Lieutenants that I have appointed have not been

mustered in, for the reason that their companies were

below the minimum.

It seems to me that all these companies should be

recruited to above the minimum before they leave for

Arizona. I am informed that the companies could easily

get recruits enough to fill them up in Monterey County

if any effort was made to do it. Please call the

General's attention to the matter.

Truly yours,

F. F. Low,

Governor.

To Lieut.-Col. R.C. Drum.

-

[Inclosure.]

Company A, Rose R. Pico, Captain; Crisanto Soto, First

Lieutenant; M.E. Jimenez, Second Lieutenant.

Company B, Porfino Jimeno, Captain; John Lafferty,

First Lieutenant; J.G. Donevan, Second Lieutenant.

Company C, Antonio M. de la Guerra, Captain; Santiago

de la Guerra, First Lieutenant; ---- Coddington,

Second Lieutenant.

Company D, Edward Bale, Captain; J. Clement Cox, First

Lieutenant; Francisco F. Guiraido, Second Lieutenant.

Note: Company C is the only one that has the minimum

number of privates.

|

Remarks on Muster Roll of Company A, First Battalion Native

Cavalry, for March and April, 1865. -- Pursuant to orders from

Headquarters Benicia Barracks, Cal., a detachment of twenty-five

enlisted men in command of Second Lieutenant M.E. Jimenez,

proceeded, on the twenty-third of April, to Green Valley and

arrested and brought to confinement ten marauders. A fight ensued,

wounding private Antonio Guilman and Juan Leon, both severely.

Remarks on Return of Company B, First Battalion Native Cavalry,

for May 1865. -- First Lieutenant John Lafferty and five enlisted

men left Camp Low, San Juan, Cal., April 10, 1865, in pursuit of

the murderers Jason and Henry, per Post Order No. 3, Headquarters

Camp Low, Cal.

The following are the stations occupied by the headquarters and

various companies as gleaned from monthly returns, muster rolls,

etc.:

Field Staff

Drum Barracks, Cal.

..........................................................................December

31, 1864.

Drum Barracks, Cal.

..................................................................................April

30, 1865.

Drum Barracks, Cal.

...................................................................................May

31, 1865.

Drum Barracks, Cal.

...................................................................................June

30, 1865.

Fort Yuma, Cal.

...........................................................................................July

31, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T.......................................................................................August

31, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T.................................................................................September

30, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T.

...................................................................................October

31, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T..................................................................................November

30, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T.

................................................................................December

31, 1865.

Company A

Camp Curtis,

Cal...................................................................................August

31, 1864.

Fort Humboldt,

Cal..............................................................................October

31, 1864.

Fort Wright,

Cal................................................................................December

31, 1864.

Fort Wright,

Cal..................................................................................February

28, 1865.

Benicia Barracks,

Cal...............................................................................April

30, 1865.

Tubac, A.T............................................................................................

August 31, 1865.

Tubac, A.T...........................................................................................October

31, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T...............................................................................December

31, 1865.

Company B

San Francisco, Cal.

...................................................................................June

30, 1864.

Presidio, San Francisco,

Cal..................................................................August

31, 1864.

Presidio, San Francisco, Cal.

...............................................................October

31, 1864.

Presidio, San Francisco, Cal.

...........................................................December

31, 1864.

Monterey Barracks, Cal.

....................................................................February

28, 1865.

Camp Low,

Cal.......................................................................................March

31, 1865.

Camp Low,

Cal.........................................................................................April

30, 1865.

Camp Low, Cal.

..........................................................................................May

2, 1865.

Camp Low,

Cal...........................................................................................

June 1, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.

T...................................................................................

August 31, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T....................................................................................October

31, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T................................................................................December

31, 1865.

- Company C

Cahuenga Pass, en route for Drum Barracks,

Cal.................................August 31, 1864.

Drum Barracks,

Cal..........................................................................December

31, 1864.

Drum Barracks,

Cal.............................................................................

January 31, 1865.

Drum Barracks,

Cal............................................................................February

28, 1865.

Drum Barracks,

Cal...................................................................................June

30, 1865.

Tubac, A.T...........................................................................................October

31, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T...............................................................................December

31, 1865.

Company D

- Drum Barracks,

Cal...................................................................................June

30, 1864.

Drum Barracks,

Cal...............................................................................August

31, 1864.

Drum Barracks,

Cal..............................................................................October

31, 1864.

Drum Barracks,

Cal.........................................................................

December 31, 1864.

Drum Barracks,

Cal...................................................................................May

31, 1865.

Drum Barracks,

Cal................................................................................June

30, 1865.

Carrisso Creek, en route via Fort Yuma to Tubac, A.T.........................July

31, 1865.

Tucson, en route for Tubac, A.T.........................................................August

31, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T............................................................................September

30, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T.................................................................................October

31, 1865.

Fort Mason, A.T..............................................................................December

31, 1865.

Tucson, en route for Drum Barracks,

Cal...........................................January 31, 1865.

-

-

Lives of the

California Lancers

The First Battalion of Native California Cavalry, 1863-1866

by Tom Prezelski

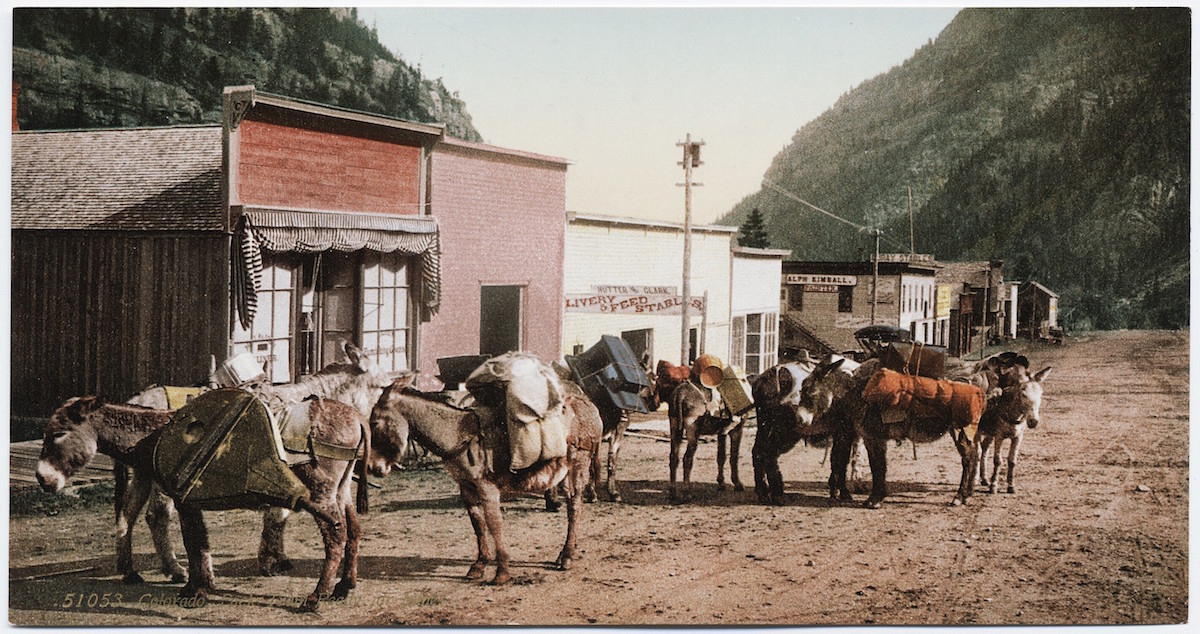

On July 4th 1865, two companies of an unusual

cavalry unit observed Independence Day in traditional Californio

style, with a bull-and-bear fight at a "grand arena" near

the old mission town of San Buenaventura. Neither the men nor their

officers seemed concerned that they were expected to ride in a parade

some sixty miles away in Los Angeles that very day. Nearly a week late

for their scheduled arrival at Drum

Barracks in Wilmington, the troopers had stopped for a few days of

rest and revelry-a break in a long overland march that would

ultimately take them to a forsaken post on the Arizona-Sonora border.[1]

These were men of companies A and B of the First

Battalion, Native California Cavalry. It was immediately obvious to

the casual observer that these troopers were different from the

thousands of other loyal Californians who had joined volunteer units

of the Union army since the beginning of the Civil War-more than half

the horsemen carried lances, a throwback of sorts to the proud

Hispanic heritage of California. The men themselves were heirs to that

tradition, or, as one correspondent put it, they were of the

"vaquero class ... natives of California or Mexico, and brought

up from youth on horseback and accustomed to the use of the lasso and

to simple fare and [the] rough herdsmen's life." [2]

As early as 1862, California state senator

Remauldo Pacheco of San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties had

observed that California's Mexican-American population (or Native

Californians in the vernacular of the day) comprised an exceptional

pool of cavalry recruits already well versed in the arts of

horsemanship and life in the field. A former officer in the Mexican

army and a Union loyalist, Pacheco was eager to give his fellow

Californios an opportunity to prove their patriotism. He proposed the

formation of a regiment of "native cavalry," which would

draw recruits from the vast ranches of Southern California and the

central coast to serve as lancers in Texas. His novel idea was well

received and, in January 1863, the War Department authorized raising a

four-company battalion.[3]

Initially, the unit was "to be commanded by

a patriotic gentleman, Don Andreas [sic] Pico" The choice was at

once inspired and ironic, for Andres Pico had commanded the Californio

lancers who humiliated a force of regular cavalry and volunteers under

Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny at the battle of San Pascual in 1846. In the

process, they not only gave the United States its only clear defeat of

the Mexican War, but also forced the previously unimpressed Americans

to recognize the skill and mettle of the California vaquero. [4]

Pico's popularity and Union loyalty made him a

good choice for the position. The aged caballero was not sufficiently

healthy, however, to ride a horse or perform many of the other duties

required of a field commander, and he never accepted his major's

commission. It was not until the recruitment of the battalion was

underway in August of 1864 that Maj. Salvador Vallejo replaced Pico.

Like Pico, the crusty Vallejo was a member of an old and established

Californio family. On the other hand, Vallejo seemed an unlikely

choice for command because of his disdain for all things Anglo. Don

Salvador was better known for his conflicts with American squatters on

his Napa Valley property than for his admiration of the Union cause.

It seems likely, given Vallejo's sentiments, that Confederate

overtures to the French backed imperialist government of Mexico drove

the dignified curmudgeon to set aside his hostility and don the blue

uniform of a United States Army officer. [5]

Even as the paper battalion languished without a

commander, a few prominent citizens, Californio and otherwise, took

the initiative and began gathering recruits for the four companies.

Jose Ramon Pico, a nephew of Andres and who later claimed to have also

fought at San Pascual, enthusiastically started the process of

organizing recruits weeks before official approval for the unit had

come back from Washington, D.C. In a flowery letter to Governor Leland

Stanford, Pico cited his credentials as a partisan Republican and,

without the slightest hint of humility, demanded a captain's

commissions [6]

Stanford granted the request, and Captain Pico

immediately gathered recruits at his personal expense. On March 3,

1863, at his headquarters on the plaza in San Jose, he spoke to an

assembled crowd in the "soul-stirring" manner for which the

men in his family were renowned:

Sons of California! Our country calls, and

we must obey! This rebellion of the southern states must be crushed;

they must come back into the union and pay obedience to the Stars

and Stripes. United, we will, by the force of circumstances become

the freest and mightiest republic on earth! Crowned monarchs must be

driven away from the sacred continent of free America!

The mention of "crowned monarchs" was

an obvious reference to the emperor Maximilian, who enjoyed not only

the support of France and conservatives in Mexico, but apparently of

the Rebel government in Richmond as well. Clearly, Pico sensed that

sentiments linking Imperial Mexico and the Confederacy as mutual

enemies of California were rife within the Spanish-surnamed

community.[7]

Pico's bluster and fiery rhetoric "infused

with martial spirit" the Native Californians of San Jose. Even

before his speech, Pico had already enlisted more than fifty recruits,

mostly from the San Jose area. Many of the Califormos showed up with

their lassos, "a novel weapon of offense. . . which they are

exceedingly expert at using on horseback." The eighty-one

recruits of Company A trained at the Presidio of San Francisco that

summer. By August, a dozen men had deserted, a sign of troubles that

would plague the battalion during its entire existence.[8]

Although the enlistees were skilled horsemen,

trained and drilled as lancers, it is unlikely that Company A was

quite what Senator Pacheco had in mind when he proposed a unit of

"native" cavalry. Many of the Spanish-surnamed recruits were

foreign born, primarily from Mexico and Chile, and seem to have been

former miners. The unit contained a number of non-Hispanic recruits as

well. A San Francisco journalist later described the company as

"truly a mixture of colors and tongues, the men rugged and

hearty-more than half being native Californians and the remainder

Mexicans, Chilenos, Sonorans, California and

Yaqui Indians, Germans, Americans, etc." [9]

In December, the colorful lances adorned with

red pennons were replaced by Sharp's carbines and Company A sailed

north by steamer to Humboldt Bay, where it joined an ongoing campaign

against the Hupa, Wintun, and other Indians in the northern region of

the state. Its duties in the redwood country included escorting

prisoners, livestock, and supply trains, but little actual fighting.

While the company was posted at Fort Gaston in February 1864, four

more men deserted and this time robbed a local civilian. A detachment

rode out in pursuit and quickly apprehended the culprits.[10]

While Company A campaigned in the northern part

of California, Capt. Ernest Hippolite LeGross was recruiting Company B

in San Francisco. A French expatriate who had served with the Corps

d'Afrique in Algeria and the Crimea, he was commissioned in part on

Pico's recommendation. Contrary to Pacheco's original vision for the

battalion, the majority of Captain LeGross's original recruits were

Frenchmen, including at least two fellow veterans from Algeria. Like

Company A, Company B was inducted into federal service at the Presidio

of San Francisco, where it remained until January 1865.[11]

Recruitment of vaqueros from the vast ranches in

the southern part of the state-the so-called "cow

counties"-did not begin until early 1864. A drought had

devastated many of the old ranches in Santa Barbara and San Luis

Obispo counties and even the prominent de la Guerra family was forced

to sell much of its vast holdings. Newly unemployed ranch hands from

the area formed the core of Company C, recruited by Capt.

Antonio Maria de la Guerra. State Senator Ramon J. Hill, a

secessionist elected from San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties,

lamented the choice of de la Guerra, pointing out that he "does

not even write fluently in his own language, knows not one word of

English, knows not what figures are-but is an experienced

horseman." Still, even Hill later admitted that "the men

will not be kept together for any other captain."[12]

Company C was very much a de la Guerra family

operation, which explains its high morale and low desertion rate.

Other de la Guerras in the company included Ist Lt. Santiago de la

Guerra and 1st Sgt. Juan de la Guerra. Also present was 2d Lt.

Porfirio Jimeno, the captain's nephew and stepson of Dr. James Ord,

brother of a Union general as well as a prominent surgeon and rancher.

Educated at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., the twenty

four-year-old Jimeno was the most intellectually well equipped of the

battalion's officers and would prove to be one of the best.[13]

Mustering of the company was delayed until July

because of rumors that raised suspicions about the officers' loyalty.

In the intervening two months, the already financially strapped

Antonio Maria de la Guerra quartered the full-strength company of

recruits at his own expense. According to the de la Guerra family and

their political allies, the rumors arose from a clique of political

rivals, who sought to diminish the de la Guerras' influence by

preventing them from receiving officers' commissions. The issue was

apparently resolved by late June and, by late August, Company C was on

the march toward' Drum Barracks. [14]

Meanwhile, Capt. Jose Antonio Sanchez had

already recruited Company D in Los Angeles. He was anxious to reverse

the work of his brother, Sheriff Tomas Sanchez, a Democratic Party

boss who, early in the war, had provided militia arms to Rebels

operating in Arizona and New Mexico. Again taking advantage of

anti-imperialist sentiment among the Spanish-surnamed Angelenos,

Sanchez enrolled eighty-nine volunteers. As with Company C, politics

and doubts about officers' loyalty delayed mustering in until March at

nearby Drum Barracks. At the same time, Juan J. Moreno, another

prominent local citizen, took the initiative in April and recruited

forty men for a Los Angeles company. But after languishing at Drum

Barracks without any word from department headquarters, Moreno and his

volunteers apparently lost interest in federal service and dispersed

by the end of May. [15]

Sanchez's enthusiasm for military service also

quickly waned. Already overwhelmed by the paperwork involved in

commanding a company, in June Sanchez and 1st Lt. Jose Redona resigned

in frustration over what they saw as poor treatment of their men,

exacerbated by a currency crisis in Los Angeles caused by an influx of

nearly worthless federal scrip. While Sanchez remained active in

promoting the Union cause in secessionist southern California, command

of his men went to Capt. Edward Bale, promoted from Company B. A

native-born Californian proficient in Spanish, Bale was respected in

the Californio community [16]

In September, de la Guerra's Company C joined

Bale's Company D at Drum Barracks. Post commander Col. James Curtis

apparently had a low opinion of the native troopers and put them to

work on a massive irrigation project to carry water from the San

Gabriel River to Wilmington. Although other officers protested the

treatment of the Californios and the use of federal soldiers for a

private project, the construction continued until January 1865 with

the troopers also marching in parades and patrolling the waterfront

and guarding federal property at nearby San Pedro amd Wilmington. [17]

Frustrated by ditch digging and the general

dullness of service, Major Vallejo resigned at the end of February,

gruffly dismissing his tour of duty as "devoid of interest."

Three weeks later, Maj. John C. Cremony transferred from the Second

Cavalry, California Volunteers, and took command of the battalion.

[18]

Although an Anglo, Cremony possessed many assets

that well-suited him for his new command. First, he was adept at

languages, including Spanish and four other tongues. Second, the

colorful officer and sometime journalist seemed to understand and have

a fondness for the Californios, even affecting the flamboyant dress of

a vaquero. Third-and perhaps most important in the coming year-he was

a veteran campaigner in Apacheria, including a stint (1851-1852) as

interpreter for the Bartlett Boundary Commission, as well as his more

celebrated (and exaggerated) role with the California Column in 1862.

[19]

As it happens, Vallejo quit just as things were

becoming more interesting for the battalion. In November of 1864,

bandits John Mason and Jim Henry held up a stage on the road from

Watsonville to Visalia, killing three men and vowing to "slay

every Republican they would meet." Under the pretense of being

Confederate guerrillas, Mason's and Henry's gang terrorized Monterey

County and its environs for the next several months.[20]

Company B, newly posted to Camp

Low at San Juan, comprised the entire cavalry force in the county.

In a letter to Governor Frederick Low, post commander Maj. Michael

O'Brien, Sixth California Infantry, described the arrival of the

troopers in late January 1865:

The gay and gallant Spanish lancaroes [sic]

came dashing through the town with the lances in their hand, a flag

flying from each of them. I assure you that they presented a warlike

appearance, the people here had never seen a soldier in their

lives-Yes sir! they even stampeded the Spanish cattle that were so

poor before that they could scarcely stand alone.

Shortly thereafter, O'Brien received

intelligence about the location of Mason's and Henry's hideout. Early

one Sunday morning a detachment of a dozen Native cavalrymen under 1st

Lt. John Lafferty rode out to find the bandits. Unfortunately,

Lafferty was unsuccessful and the gang continued its depredations.[21]

Meanwhile, drastic changes were taking place for

Company B. In March of 1865, Captain LeGross resigned in the face of

declining morale that produced forty desertions in a little less than

a year. Promoted from Company C, Capt. Porfirio Jimeno, the new

company commander, replaced the mostly French and Anglo deserters with

Hispanic recruits. This improved morale somewhat by making the company

more "native" in character.[22]

In April, word arrived at San Juan that the

Mason-Henry gang had struck at Firebaugh's Ferry. Captain Jimeno,

temporarily in command of Camp Low, sent Lieutenant Lafferty and a

detachment of five men in pursuit of the bandits. Hoping to cut off

the gang at Panoche Pass, the lancers rode south along the western

flank of the Diablo Range and encountered Mason the next morning. As

the bandit spurred his horse in a desperate attempt to escape,

Lafferty fired, wounding Mason in the hip and felling his mount with a

single bullet. Although the soldiers captured the outlaw's horse,

somehow Mason managed to elude them. At six that evening, Lafferty and

his troopers returned to Camp Low with the horse in tow. Captain

Jimeno boldly vowed to continue the pursuit of Mason and Henry,

unaware that he and his new command soon would be otherwise occupied.[23]

Similar troubles erupted in the Mohave Valley,

where secessionist sentiment ran high, and Chimehuevi Indian

depredations plagued the local residents. In response, Captain Bale

and Company D were sent to Camp

Cady on the road from Cajon Pass to Fort Mohave. Only thirty of

Bale's men were mounted as cavalry; the bulk of the company served on

foot and was equipped with model 1842 muskets left over from the

Mexican War. The Californios performed routine garrison and patrol

duties through March and were back at Drum Barracks by April 9, in

time to prepare for a new assignment.[24]

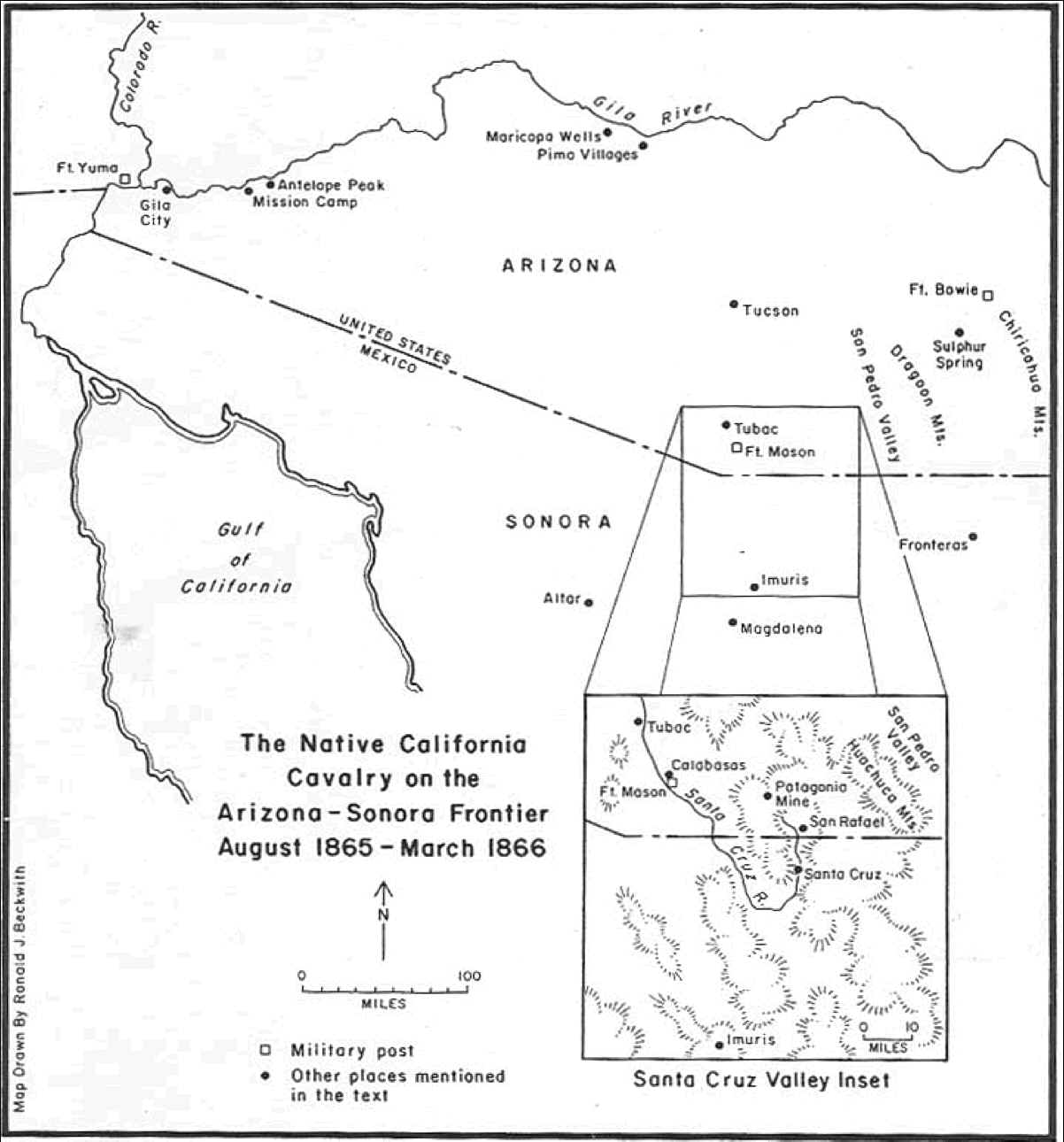

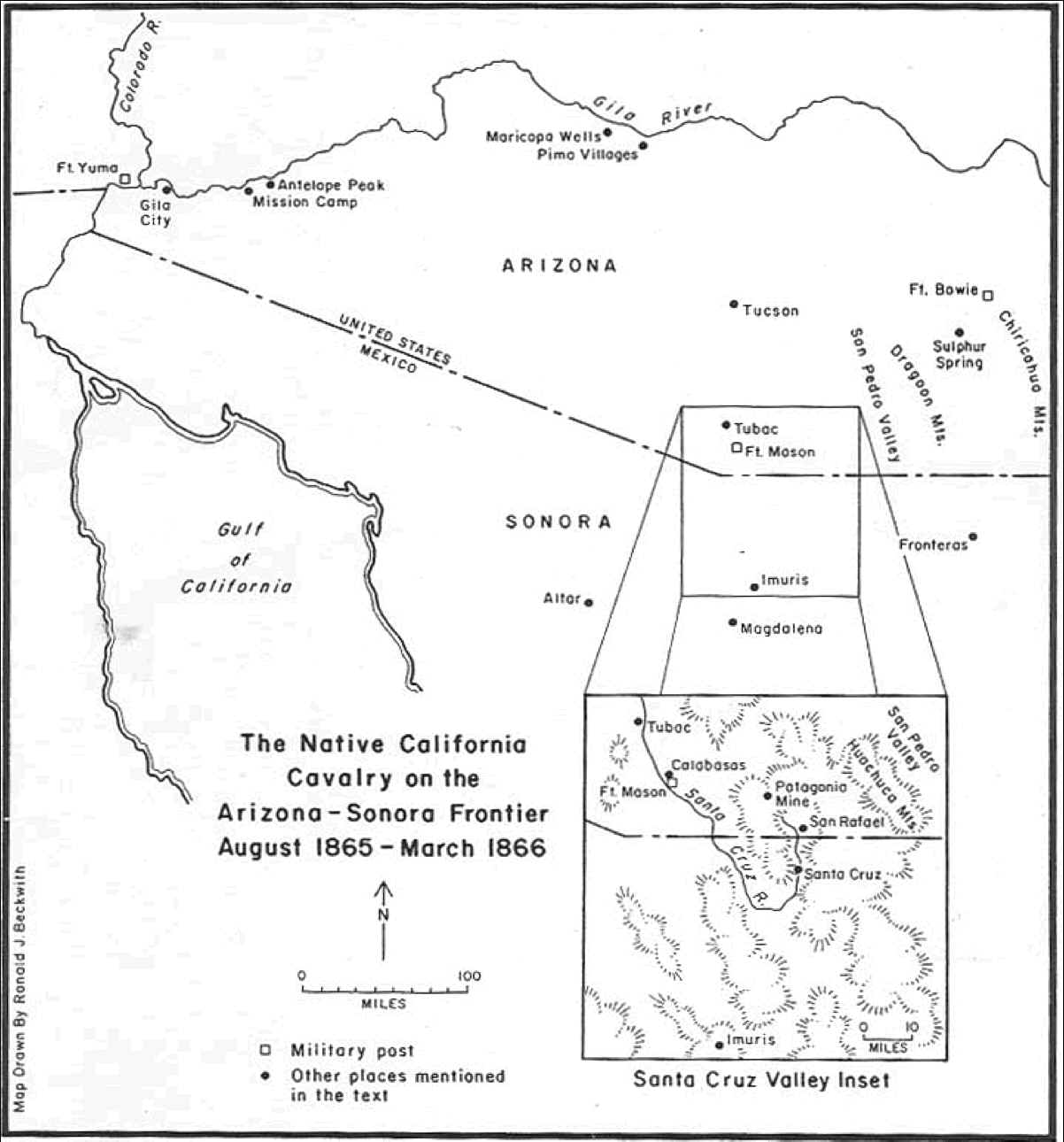

In March 1865, Brig. Gen. John S. Mason, newly

appointed commander of the District of Arizona, announced that the

battalion of Native Cavalry would be traveling east to fight Apaches.

Company A assembled at Benicia Barracks on the mouth of the Sacramento

River in early April, where it began preparations for the nearly

thousand-mile march. Meanwhile, Major Cremony arrived at Camp Low with

headquarters and Company B.[25]

Reports of President Abraham Lincoln's

assassination reached the West Coast on April 15, delaying the

departure of the two Native companies. Major Cremony, Captain Jimeno,

and Lieutenant Lafferty served on the committee that planned Monterey

County's memorial observance, and on April 19, Company B participated

in a procession through the streets of San Juan. Meanwhile,

detachments of both companies were assigned to quell violence and

arrest men caught "rejoicing" at the news of the president's

death. Disturbances occurred across the state, and in response,

detachments were sent as far away as Grass Valley, where twenty-five

troopers of Company A under Lt. Marcelino Jimenez arrested ten

individuals after a skirmish that left two Native Cavalrymen wounded.[26]

By June, companies A and B were united at San

Juan. On June 3, the eve of the Californios' scheduled departure for

Arizona, two secessionists arrested in the wake of President Lincoln's

death escaped from the Camp Low guard house. Major Cremony detailed

both companies to hunt for the fugitives. After a week of fruitless

searching, on June 16, troopers began the long march that would take

them first to Drum Barracks and then to their new station at Tubac,

Arizona Territory. Although they were expected at Drum Barracks by the

Fourth of July, the cavalrymen marched leisurely south along the

coast, their pace slowed not so much by their sizeable stock train

that included "14 fine mules and some 300 horses," as by

their frequent stops for fandangos and bull-versus-bear fights.[27]

The arrival of Major Cremony's column at Drum

Barracks on July 9 represented the first time that the First

Battalion, Native California Cavalry, was assembled in one place.

Companies C and D were now fully mounted and armed, thanks in part to

Captain Pico's uncle, don Pio Pico, who supplied the garrison with

horses. Capt. Thomas Young, a veteran of service in New Mexico and

Arizona, was now in command of Company D, replacing Captain Bale who

had resigned in May. [28]

Like the California Column three years earlier,

the Native California Cavalry departed at staggered intervals in order

to conserve water and forage on its journey across the desert. Company

A left Drum Barracks on July 13, followed by Company B on the

fifteenth and Company D on the twenty-first. For reasons that are

unclear, Company C with Major Cremony and his staff remained behind

until September. During the two-week march to Fort Yuma, the three

companies spread out for seventy-five miles along the famous Overland

Road. [29]

Captain Jimeno, for one, questioned the wisdom

of crossing the Mojave and Sonoran deserts in July and August. In a

letter home, the gloomy and cynical commander of Company B warned his

uncle Pablo de la Guerra of the perils of such a journey:

For Heaven's Sake never come out here if

you can help it; you will surely melt. Thermometer every day in the

shade 112 to 116-wind none-Scorpions thick as molasses, flies still

worse and when we want to drink cool water we have to boil it and

drink it immediately or else it will get hotter. Es imposible dan

una description de esta punto. [30]

Dallying at Fort Yuma only long enough to

bivouac for a few days, the Californios continued on toward Tubac. The

route would have been familar to the ancestors of most of the

California-born men of the battalion, as well as to many of the

troopers of Mexican birth, since it was the same route they had

followed in the opposite direction from Sonora to California years

before. On August 9, Company D once again took up the rear of the

column, escorting a supply train that included two light artillery

pieces.[31]

Six men deserted Company A during the first five

days out of Fort Yuma,

while Company B lost twenty men. Because the desertions occurred as

the column passed through the lower Gila Valley, where the prosperous

but short-lived mining camp of Gila City had existed only a few years

before, it may be that the abscounders, some of whom were ex-miners,

ran away to try their hand at placer mining, either near Gila City or

a few days north at La Paz. It is also possible that some of the

fugitives fled south along the Camino del Diablo, which linked up with

the Overland Road in the same area, and sought sanctuary in Sonora.[32]

A night march across the forty-mile desert, a

week or so out of Fort Yuma, brought Company D to the Maricopa

villages. After more than three weeks on the trail, the Native

cavalrymen cast envious eyes on the melons ripening in the fields.

According to 1st Sgt. Juan Robarts, the "men having a sneaking

regard for the fruit," but having no hard currency, paid the

enterprising Indians with "their shirts, drawers, and other

articles of apparel." In Robarts's estimation, the Maricopas

"got the best of every trade that was made."

Arriving in the Old Pueblo on August 30, Robarts

had nothing nice to say about what he sarcastically referred to as the

"flourishing and extensive city of Tucson." After a day's

rest, Company D resumed its march south on September 1. Two nights

later, a corporal on guard duty spotted "eight or ten"

Apaches, the Califormos' first encounter with the desert warriors.

Apparently the Indians had "only come to see if they could find a

horse or mule loose, or picketed outside of camp," and nothing

came of the brief sighting.[33]

The following day the Los Angeles company

arrived at Tubac, only to find the ancient presidio all but abandoned

and the military post moved a dozen miles south to the old hacienda of

Calabasas. There they joined companies A and B and three companies of

the Seventh Infantry, California Volunteers, all under the command of

Lt. Col. Charles Lewis, a competent and decisive officer who led the

"Hungry Seventh." [34]

Named Fort Mason after Gen. John S. Mason, who

commanded the District of Arizona from his Fort Whipple headquarters

near Prescott, the new post could hardly be called a fort, consisting

instead of tents and brush shelters and only a few permanent

buildings. The site, selected by Colonel Lewis, was the former

location of Camp Moore, occupied by two companies of the First

Dragoons for a few months in 1856.

Lewis probably did not foresee the problems that

would plague Camp Mason. Unusually heavy monsoon rains in August and

September swelled the Santa Cruz River and its tributaries. Water that

accumulated in the arroyos and cienegas provided an ideal environment

for mosquito-borne fever that prostrated the garrison throughout the

fall and winter. Five enlisted men of the Native California Cavalry

and two of its officers, 1st Lt. Crisanto Soto of Company A and Capt.

Thomas A. Young of Company D, eventually died of the disease. At one

point, between one-third and one-half of the garrison was laid low.

The fever slowed construction of the post to a near standstill and

delayed serious forays against the Apaches.[35]

Despite its problems, Fort Mason was

strategically located on the most important road leading from Tucson

into Sonora. Stationed at an important listening post less than ten

miles from the border, the men of the Native California Cavalry found

themselves only a few hours ride from Mexico, a nation occupied by a

foreign power and mired in turmoil that threatened the United States.

Sonora was so far removed from Mexico's central

government that in many ways it was effectively independent. The

political chaos that consumed the rest of the country did not leave

the frontier province untouched, however. Governor Ignacio Pesquiera,

a Liberal of convenience, had been fighting to retain the governorship

since 1855 against partisans of his predecessor, Conservative Manuel

Gandara, who sought forcibly to unseat him. Gandara's support

collapsed in 1861, and he was exiled just in time to miss the coming

French invasion.A supporter of the Republicans under President Benito

Juarez, Pesquiera was friendly to the Union cause during the American

Civil War. He resisted overtures from Confederate agents and

cultivated friendships with federal officers, including Colonel Lewis

and Col. James Carleton of the California Column. These amicable

relationships were born not only out of pragmatism, but also out of

partisanship, for the French-backed Imperialists maintained ties with

the Confederacy, while the Union generally favored the Republican

faction. [36]

While Sonora remained more or less unaffected by

the war in central Mexico, Pesquiera managed to retain his

governorship during the early part of the French Intervention. That

changed in 1865 when French regulars landed at Guaymas in hopes of

seizing the fabled Sonoran silver mines and using the loot to defray

the high cost of supporting Maximilian's monarchy. The French

movements alarmed United States officials in California, who had

received reports that the Imperialists sought to overturn the Gadsden

Purchase and reclaim Arizona. Sonoran Conservatives were encouraged.

They assisted a small-but-disciplined foreign force in destroying

Pesquiera's ragtag and demoralized army, forcing him

to flee to the safety of his friends north of the border.

Major Cremony, who was not yet present at Fort

Mason, later wrote an account of Pesquiera's September 6 arrival at

the post that seemed to imply that the exiled governor stumbled into

American territory with a force of French regulars in rapid pursuit at

his heels. The reality seems to have been somewhat different.

Accompanying the governor was a sizeable entourage that included his

family, sheep, goats, a thousand head of cattle, a hundred horses, and

a military escort. Col. Federico Ronstadt, an infantry officer in the

Republican army, rode ahead of the party and requested permission to

camp in the valley below Fort Mason. According to Sergeant Robarts of

Company D, "Colonel Lewis replied that he and his officers would

do themselves the honor to wait on the Governor of Sonora, which

accordingly they did, and offered the protection and hospitality of

the post." Pesquiera camped with his entourage in the shadow of

the fort before briefly taking up residence at the nearby hacienda of

Calabasas. He then moved on to Tubac and established a sort of capital

in exile, where he could gather financial resources and recruits for a

new army. [37]

Meanwhile in Sonora, Jose Moreno, prefect of the

military district of Altar, moved "300 or 400 Mexican

Imperialists" to Magdalena, some fifty-five miles south of Fort

Mason, apparently with the intention of crossing the border to seize

the governor. Colonel Lewis belligerently declared, "Let him come

and try it!" War seemed inevitable, and the boredom and misery of

garrison life only amplified the tension. [38]

The situation may have been too much for fifteen

men of companies A and B, who deserted shortly after Pesquiera's

arrival and fled south with thirty horses and "numerous"

pistols and carbines. Receiving word that the deserters were at

Magdalena, Captains Pico and Jimeno, along with Lt. William Emery of

the Seventh

California Infantry and thirty men of Company A, Native California

Cavalry, set out to recover the deserters and the stolen property.

A two-day ride brought the detachment to the

outskirts of the Sonoran community, where Captain Pico sent Emery

forward as a messenger. Impatient for Emery's return, Pico selected

eight to ten men and charged into the town. Stopping in front of

Prefect Moreno's office, the Californio boldly demanded the return of

the deserters and stolen property, as well as safe passage for himself

to Altar and Hermosillo. During the ensuing heated argument, Pico

arrogantly declared that as an American officer, he did not recognize

the Imperial government. A crowd that assembled in the plaza cheered

the blue-coated invaders. Like everyone else in Magdalena, Moreno

assumed that Pico was there to start a fight. Consequently, he

assembled ten to twenty cavalrymen in a line opposite the Californios

and sent for an infantry detachment camped nearby. "A single gun

fired at this moment would have started a general fight," one

California soldier later wrote.

For some reason, perhaps the intervention of the

cooler headed Lieutenant Emery, the situation calmed somewhat and

Prefect Moreno agreed to send a courier to Hermosillo for

instructions. Captain Pico, for his part, agreed to send Captain

Jimeno and the bulk of the detachment, who still remained outside the

town, back across the line. During the eight-day wait for the

messenger to return, Republican sympathizers in Magdalena treated

Pico, Emery, and the small escort of Native cavalrymen who had been

permitted to stay with them to "three fine dinners." Pico's

request for safe passage into the Sonoran interior was refused and the

proud Californian was forced to return home empty-handed. On the way

back, the Californios spotted five Apaches in the hills overlooking

the road. So that the expedition would not be a total loss, Pico

ordered his troopers to give chase. Lieutenant Emery narrowly escaped

injury as his horse lost its footing on the steep and rocky incline.

Captain Pico burned himself severely when his pistol discharged as he

fell with his horse. The incident no doubt humiliated Pico, who had a

reputation as one of California's finest horsemen. He called off the

chase and the humbled Californians returned to Fort Mason on September

15. The next day, word arrived that Moreno's men had auctioned off the

federal property the deserters had stolen. [39]

In the wake of Imperialist protests against

Pico's belligerent behavior and an apparent accompanying buildup of

French and Imperialist troops near the border, Colonel Lewis

established an outpost at Sylvester Mowry's recently abandoned

Patagonia mine and sent a twenty-man detachment from Company D to

patrol the line. Meanwhile, a rumor reached California that Pico was

being held prisoner in Mexico and would be executed by the

French-backed Imperialists at Hermosillo. [40]

Major Cremony finally arrived at Fort Mason,

together with Captain de la Guerra and Company C, in early November. A

three week delay at Fort Yuma-possibly due to flooding-and Cremony's

visit with the ailing Governor Pesquiera at Tubac had slowed the march

from Drum Barracks. Now the Native California Cavalry battalion was

once again assembled, just in time to respond to a threatened

Imperialist invasion of southern Arizona. [41]

Late on the night of November 24, word reached

Fort Mason from Patagonia that a large Sonoran force had attacked the

ranching community of San Rafael, just north of the border. About 350

Opata volunteers under the command of Col. Refugio Tanori, an Opata

leader commissioned in the Imperial Army, had crossed the line on an

apparently botched raid that left an American citizen wounded.

Believing that the raid was an attempt to capture Pesquiera, Major

Cremony quickly assembled a detachment from companies C and D and rode

across the Patagonia Mountains, reaching San Rafael early the next

morning. From there, Cremony crossed the border and entered the town

of Santa Cruz, where he learned that Tanori's command had retreated

farther south. The major sent ahead 1st Lt. Edmund W. Coddington of

Company D and ten troopers to make contact with the Imperialist

colonel. After a forty-mile ride, the troopers reached Imuris only to

find that Tanori and his irregulars had melted into the countryside.

After resting a few days at Santa Cruz, the command returned to Fort

Mason, where it arrived on November 30. [42]

By the time of Tanori's raid, the French

regulars had largely withdrawn from Sonora. Pesquiera and the

Republicans, while, had successfully raised a small army to challenge

Imperialist authority in the frontier state. Increasingly through

December and January, Republican forces engaged the Imperialists in

battle in the heart of Sonora. Although the war was far from over, the

Imperialists would never again molest the northern regions.[43]

At the same time, frontier privations and the

especially miserable conditions at Fort Mason took their toll on the

men of the Native California Cavalry. Company returns signed by

Cremony in December show a battalion that, although fairly well

disciplined, was scarcely ready to fight. Arms for companies B, C, and

D, including the distinctive lances that were once such a source of

pride, were listed as unfit for service. Accoutrements and clothing

were also in bad shape. Despite the Californios' evident unreadiness

for field service, General Mason was contemplating a campaign against

Cochise that involved the 'men of Fort Mason. [44]

For much of the Native Cavalry's service at Fort

Mason, the much-talked-about Apaches were nowhere to be seen in the

Santa Cruz Valley. A few patrols caught glimpses at a distance of

small parties of less than a dozen, and Captain Jimemo reported

killing one Apache in a brief exchange in October. Cochise had greatly

curtailed his activities north of the border, partly in response to

the troop buildup during the summer and fall that accompanied General

Mason's arrival in Arizona. [45]

Mason's plan called for troops from Forts Mason

and Bowie to conduct a two-pronged campaign against the Chiricahua

Apaches. Colonel Lewis's command, including men from the Native

Cavalry and his own Seventh California Infantry, started from Fort

Mason in late December, then split into three detachments that scouted

the San Pedro Valley and the Huachuca and Dragoon mountains. Captain

Jimeno's cavalry tracked a party of Apaches to an encampment at

Sulphur Springs on Christmas Eve. Attacking from ambush, the

Californios killed one Indian, wounded two others, and scattered the

remainder.

Several days later, Lewis and the rest of the

expedition joined Jimeno's troopers at the ambush site. Striking north

and west, the California Volunteers eventually reached Fort Bowie,

where they were joined by noted scout Merejildo Grijalva. By January

6, the command was in the field again, tracking Cochise's band in: the

Chiricahua Mountains. Although at one point the Californios observed

sixty to seventy warriors at a distance, the Apaches constantly

remained a few steps ahead of Lewis's troops. The pursuit continued as

far south as Fronteras, Sonora, where the frustrated colonel turned

back toward home, blaming the expedition's failure on Captain Jimeno,

despite the fact that the Native troopers produced the only tangible

success of the campaign. Fortunately for Jimeno, department

headquarters in San Francisco, unaware that the Chiricahua Apaches had

largely withdrawn from Arizona in the pervious months, proclaimed the

expedition a success, since it appeared to them that Cochise had been

driven into Mexico. [46]

Even before Major Cremony arrived at Fort Mason

back in November, orders had been issued for the dissolution of his

battalion. On October 21, 1865, department headquarters at San

Francisco instructed the Native California Cavalry to return to Drum

Barracks for mustering out. By early December, detachments that had

remained behind to guard federal property at Camp Low, the Presidio,

and Angel

Island had been relieved by regular troops and discharged. A few

more months would pass, however, before regulars arrived in Arizona.

So the bulk of the battalion remained at Fort Mason until late

January, when it began its long march home. [47]

Reaching Tucson on January 31, 1866, the

Californios retraced their route along the Overland Road to the

Colorado River opposite Fort Yuma, where high water from heavy autumn

rains forced them to stop for over a week. As soon as they were able

to ford the river and reach the fort, the battalion split up, with

companies A, B, and D marching overland to Drum Barracks, while Major

Cremony and Company C boarded a steamer for the Presidio. The Santa

Barbara company may have received this special treatment because of

the poor health of Captain de la Guerra. Suffering from a social

disease that he caught some time during his service, the captain had

been confined to quarters during much of his stay at Fort Mason and

was likely unable to withstand the rigors of a road march. [48]

Lagging behind the other two companies traveling

over land, Company D reached Drum Barracks on March 8, joining

companies A and B who had arrived there a week earlier. Captain Jimeno

and Company B were mustered out on March 15; the other two companies

were discharged five days later. One news paper correspondent tersely

summarized the Californios' tour of duty. "They have done good

service," he wrote. [49]

The journey home for Major Cremony and Company C

took somewhat longer. Together with a company of the Seventh

California Infantry and two companies from the Second California

Infantry, the remaining Californios boarded a Colorado River steamer

at Fort Yuma and sailed south to Cabo San Lucas at the tip of Baja

California. After a few days stopover, they continued the voyage

around the peninsula and then north to San Francisco, where they

docked on March 27. [50]

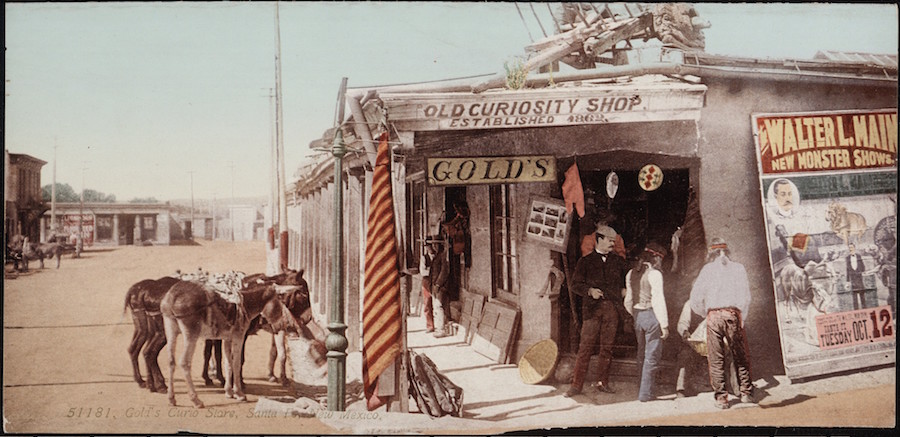

At the Presidio on April 2, the men of Company C

were mustered out, given their back pay, and let loose in San

Francisco, where they were "to be seen on every street corner. .

. spending their greenbacks with great liberality." The

ex-lancers, threadbare after their frontier service, spent most of

their newly issued scrip at clothing stores. [51]

The veterans of the Santa Barbara company were

welcomed home with a parade down the dusty lane that would become

State Street and a two-day fiesta in De La Guerra Plaza. The events of

the Civil War and their political fallout had given the old families

of Spanish California power and prestige that they had not enjoyed

since the American conquest. Now, the return of the vaqueros, who had

served their country in the best tradition of the valiant lancers of

San Pascual, gave the Californios a chance to celebrate this brief

moment when the glory and romance of Old California seemed restored.

Perhaps they knew that it was not to last. [52]

Porfirio Jimeno was offered a commission in the

postwar regular army, but turned it down. Instead, he went to Mexico,

possibly to join members of his father's family, or, according to some

reports, throwing in with the American Legion of Honor, a band of

ex-California Volunteers who aided the Republican cause in Mexico.

Either way, he died a commissioned officer in the Mexican Army at

Mexico City in 1870. [53]

Antonio de la Guerra continued to suffer from

the illness he contracted in the service. Treated with injections of

mercury, he died blind and toothless at age fifty-six in 1881. [54]

The other officers and men of the Native

California Cavalry returned to their civilian lives. Like most of the

California Volunteers, they faded into obscurity, forgotten by nearly

everyone except when the proud veterans appeared at the battalion

reunions held at Drum Barracks until 1923. The last Californio lancer,

1st Sgt. Juan de la Guerra of Company C, died at Santa Barbara in

1945. [55]

Well before Sergeant de la Guerra's death, the

tradition that the Native Cavalry represented had become a throwback,

seen only in popular novels like Ramona and The Mark of Zorro. Even as

the battalion served in California and Arizona, the big ranches were

being broken up and sold. The end of the war brought an influx Anglos

ignorant of California's past and thus unable to respect the

contributions of their Spanish-surnamed predecessors. The charge of

the lancer, with brilliant pennon fluttering in the wind blowing in

from the sea, had become as quaint a romantic notion as the sprawling

rancho and the vaquero. The service of the First Battalion of Native

California Cavalry was one last chance for the proud California

vaquero to ride into glory. [56]

Footnotes

1. San Francisco Bulletin, July 11, 1865;

Wilmington Journal, July 1, 8, 1865.

2. Officially, the armament of the lancer

companies of the Native California Cavalry consisted of a Colt army

revolver, a saber, and a lance manufactured at the Benicia arsenal.

Special Order 65, Headquarters, District of Southern California, Drum

Barracks, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in

128 pts. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901),

Series I, vol. 50, pt. 2, p. 1035 (hereinafter cited as O.R.); San

Francisco Bulletin, July 8, 1865.

3. Richard H. Orton, Records of California

Men in the War of the Rebellion (Sacramento: State of California,

1890), p. 304; Sacramento Union, January 28, 1863.

4. Orton, Records of California Men, p.

304; Leonard Pitt, The Decline of the Californios: A Social History

of Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846-1890 (Berkeley: University

of California Press, 1966), p. 34.

5. Orton, Records of California Men, p.

304; Pitt, Decline of the Californios, pp. 230, 233.

6. Wilmington Journal, March 10, 1866 J.

R. Pico to Governor Stanford, San Jose, January 2, 1863, Box 6,

Military and National Guard Collection (MNG), California Archives,

Sacramento.

7. Alta California (San Francisco), March

11, 1863

8. Ibid., March 11, 20,1863; Orton, Records

of California Men, pp. 307-310.

9. Muster and Descriptive Roll, Native

California Cavalry (NCC), MNG; San Francisco Bulletin, July

8, 1865.

10. Aurora Hunt, The Army of the Pacific: Its

operations in California, Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Nevada,

Oregon, Washington, plains region, Mexico, etc. 1860-1866 (Glendale,

Calif.: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1951), pp. 246-48; A. J. Bledsoe,

Indian Wars of the Northwest: A California Sketch (Oakland,

Calif.: Biobooks, 1956), pp. 234, 249-51; Alta California,

February 18, 1864.

11. San Pose Patriot, January 18, 1863.

J. R. Pico to Governor Stanford, September 9, 1863, Box 6; and Muster

and Descriptive Roll, Company Returns, Company B, NCC, both in MNG.

12. A. Dibblee Poett, Rancho San Julian: The

Story of a California Ranch and Its People (Santa Barbara: Futhian

Press, 1990), pp. 3-38. Maj. S. Vallejo to Lt. Col. Richard C. Drum, Drum

Barracks, April 13, 1864; Raymond Hill to Governor Low, Santa

Barbara, April 24, 1864; Hill to General Kibbe, Santa Barbara, May 16,

1864, Box 7, MNG. Muster and

Descriptive Roll, Company C, NCC, ibid.

13. Constance Wynn Altshuler, Cavalry Yellow

& Infantry Blue: Army Officers in Arizona Between 1851 and 1886

(Tucson: Arizona Historical Society, 1991), pp. 178-79; Stella

Haverland Rouse, "Civil War Volunteers," Noticias

(Santa Barbara Historical Society), vol. 27 (Fall 1981), pp. 58-59.

14. Pablo de la Guerra to Low, Los Angeles, May

26,1864; W. G. Still to Low, Los Angeles, May 27, 1864, Box 7, MNG.

Alta California, June 18, September 11, 1864.

15. Pitt, The Decline of the Californios,

p. 231. Jose J. Moreno to Low, Los Angeles, April 28, 1864; Still to

Low, May 27, 1864, Box 7, MNG. Post Returns, Drum Barracks, March

1864, Records of the U.S. Army Commands (RUSAC), Record Group 94,

National Archives.

16. William P. Reynolds to Low, Los Angeles,

June 9, 1864, Box 7; Vallejo and Pico to Stanford, Presidio of San

Francisco, November 30, 1863, Box 6, MNG. Alta California,

June 24, 1864. Post Returns, Drum Barracks, July 1864, RUSAC.

17. Post Returns, Drum Barracks, September 1864,

RUSAC; Reynolds to Low, Los Angeles, March 28, 1864, Box 7, MNG; Wilmington

Journal, January 14,1865; Haverland Rouse, "Civil War

Volunteers."

18. Pitt, Decline of the Californios, p. 233;

Orton, Records of California Men, p. 301.

19. Altshuler, Cavalry Yellow & Infantry

Blue, p. 85.

20. Parajo Times (Watsonville), November

12, 1864.

21. Alta California, January 24, 1865; Michael

O'Brien to Low, Camp Low, San Juan, February 1, 1865, Box 8, MNG.

22. Vallejo to Low, Drum Barracks, February 23,

1865; Captain de la Guerra and Lieutenant Jimeno to Low, March 17,

1865, Box 8, MNG. Orton, Records of California Men, pp.

310-14.

23. Alta California, April 12, 13, 1865.

24. OR., pp. 1150-51; Post Returns, Drum

Barracks, March and April 1865, RUSAC.

25. Sacramento Union, March 11, 1865; Alta

California, April 12, 1865.

26. Pajaro Times, April 29, 1865; Sacramento

Union, April 28, 27, 1865; Alta California, May 14, 1865;

Orton, Records of California Men, p. 305.

27. Monterey Gazette, June 9, 1865; San

Francisco Bulletin, July 8, 1865.

28. Post Returns, Drum Barracks, July 1865,

RUASC. Alta California, April 12, 1865. Company Returns,

Company D, NCC, June 1865, MNG; Gilbert C. Smith to Low, May 24,

1865, Box 9, ibid.

29. Wilmington Journal July 29, 1865; Post

Returns, Drum Barracks, July-August 1865, RUSAC.

30. Jimeno to Pablo de la Guerra, August 3,

1865, Folder 554, de la Guerra Collection, Santa Barbara Mission

Archives.

31. Los Angeles Tri-Weekly News, October

24, 1865.

32. Orton, Records of California Men, pp.

307-314.

33. Los Angeles Tri-Weekly News, October 24,

1865.

34. Ibid.; Constance Wynn Altshuler, Chains of

Command: Arizona and the Army, 1856-1875 (Tucson: Arizona Historical

Society, 1981), pp. 41-44.

35. Constance Wynn Altshuler, "Camp

Moore and Fort Mason," Journal of the Council on Abandoned

Military Posts, vol. 26 (Winter 1976), pp. 34-36; Sacramento

Union, October 19, 1865.

36. Rodolfo F. Acuiia, Sonoran Strongman:

Ignacio Pesquiera and His Times (Tucson: University of Arizona

Press, 1974), pp. 79-87.

37. John C. Cremony, "How and Why We

Took Santa Cruz," Overland Monthly, vol. 6 (April 1871), pp.

335-40; Los Angeles Tri-Weekly Times, October 24, 1865; Thomas

Edwin

Farish, History of Arizona, vol. 4, p. 118, typescript, Special

Collections, University of Arizona Library, Tucson; Edward F. Ronstadt,

ed., Borderman: Memoirs of Federico Jose Maria Ronstadt

(Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993), p. 4.

38. San Francisco Bulletin, October 23,

1865.

39. Ibid.; Sacramento Union, October 19,

1865; Los Angeles Tri-Weekly News, October 24, 1865.

40. Returns, Company D, NCC, October 31 to

December 31, 1865, MNG; Porfirio Jimeno to Josefa Maria de la Guerra,

October 30, 1865, Folder 551, de la Guerra Collection; San

Francisco Bulletin, October 23, 1865.

41. Muster Roll, Field & Staff, NCC, August

31 to October 1865, MNG; Cremony, "How and Why We Took Santa

Cruz," p. 337.

42. Cremony, "How and Why We Took Santa

Cruz," pp. 337-40; Wilmington Journal, December 30,

1865.

43. Acuna, Sonoran Strongman, pp. 87-93.

44. Returns, Companies A, B, C, and D, NCC, MNG.

45. Jimeno to Josefa Maria de la Guerra, October

30, 1865, Folder 551, de la Guerra Collection.

46. Edwin R. Sweeney, Cochise: Chiricahua

Apache Chief (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), pp.

239-40.

47. Sacramento Union, October 26, 1865; Los

Angeles Tri-Weekly News, December 15, 1865; Returns, Company B,

December 1865, NCC, MNG.

48. Wilmington Journal; February 17,

March 17, 1865; Returns, Company D, January 31, 1866, Company C,

October 31 to December 31, 1865, NCC, MNG; Diblee Poett, Rancho San

Julian, p. 42.

49. Wilmington Journal, March 3, 10,

1866; Orton, Records of California Men, pp. 307-14, 317-20; San

Francisco Bulletin, March 30, 1866.

50. Don McDowell, "Vaqueros en Azul,"

Drumbeats, vol. 3 (October 1989); Alta California, March

27, 1866.

51. Orton, Records of California Men, pp.

315-17; Alta California, April 4, 1865.

52. McDowell, "Vaqueros en Azul";

Pitt, Decline of the Californios, pp. 241-42.

53. Altshuler, Cavalry Yellow & Infantry

Blue, pp. 178-79.

54. Diblee Poett, Rancho San Julian, p.

42; McDowell, "Vaqueros en Azul."

55. McDowell, "Vaqueros en Azul."

56. Pitt, Decline of the Californios, pp.

247-76.

About the Author

- Tom Prezelski is a graduate of the University

of Arizona and a docent at the Arizona Historical Society, Tucson.

He presented an earlier version of this article at the 1998 joint

New Mexico-Arizona Historical Convention in Santa Fe.

The Pima County Board of Supervisors appointed

Tom Prezelski to the House of Representatives in February 2003 to fill

the vacancy left in District 29 by Representative Victor Soltero, who

resigned to accept an appointment to a vacancy in the State Senate.

Representative Prezelski is a Tucson native with

deep roots in the Old Pueblo and Southern Arizona. His father had a

distinguished twenty-two year career in the United States Air Force,

retiring with the rank of Senior Master Sergeant. His mother, who had

a long and varied career at the University of Arizona, is a descendent

of several pioneer families of the Arizona-Sonora border region,

including some ancestors who served as soldiers in the Spanish

garrison at Tucson in the 18th Century. His family’s tradition of

public service extends at least as far back as his grandfather,

Francisco Ronquillo Villa, a cowboy, rancher, union railroad worker

and Cochise County Democrat who served on a school board in the San

Pedro Valley in the 1930s.

Representative Prezelski is a graduate of the

University of Arizona, where he was active in the Arizona Students

Association and received a degree in Geography.

Representative Prezelski is an amateur

historian, and some of his articles have seen print. For this article

he received the James F. Elliot II award for the best article by a

non-professional historian. He has worked as a docent and volunteer at

the Arizona Historical Society in Tucson. He also participates in a

reenactment group that recreates the Segunda Compania de

Voluntarios de Cataluña, a Spanish infantry company that served

in what is now Arizona, California and Sonora in the 1780s. In 1995,

he was appointed to the Tucson-Pima County Historical Commission, a

board that advises local government about historical and cultural

preservation issues in the greater Tucson area.

Representative Prezelski worked as a planner for

the Tohono O’odham Nation from since 1999 to 2003.

Representative Prezelski lives in the Barrio

Viejo neighborhood of Tucson on the same block where his grandmother

grew up.

|

I often say that material inheritance is fleeting. Perhaps you may inherit a valuable piece of art, a home or a bundle of money. Receiving the story of your family is one of the most valuable inheritances that a person can receive. It will last hundreds of years.

Consider telling your story.

I often say that material inheritance is fleeting. Perhaps you may inherit a valuable piece of art, a home or a bundle of money. Receiving the story of your family is one of the most valuable inheritances that a person can receive. It will last hundreds of years.

Consider telling your story.

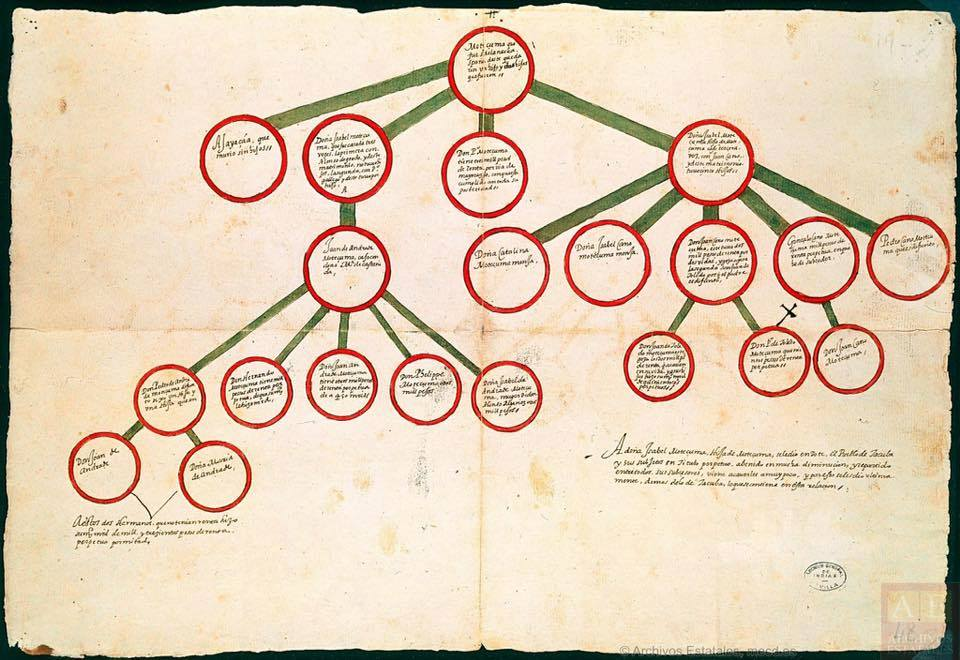

Calcula el investigador Harold Sims

(autor de «La Descolonización de México») que, entre los años 1827 y 1829, fueron expulsados de México en razón de su origen español 7.148 personas. En 1830 quedaban ya menos de 2.000 españoles en esa

región.

Los principales receptores de este éxodo fueron Estados

Unidos, Filipinas, Cuba, Puerto Rico y Europa.

No así las islas británicas. Los peninsulares, a pesar de la supuesta amistad con

Inglaterra, eran recibidos por las autoridades británicas en el Caribe con

La Muerte del Liberador

Simóon Bolivar

Calcula el investigador Harold Sims

(autor de «La Descolonización de México») que, entre los años 1827 y 1829, fueron expulsados de México en razón de su origen español 7.148 personas. En 1830 quedaban ya menos de 2.000 españoles en esa

región.

Los principales receptores de este éxodo fueron Estados

Unidos, Filipinas, Cuba, Puerto Rico y Europa.

No así las islas británicas. Los peninsulares, a pesar de la supuesta amistad con

Inglaterra, eran recibidos por las autoridades británicas en el Caribe con

La Muerte del Liberador

Simóon Bolivar

August 2, 2011

"The world is really un-informed to the facts presented here. There is no such thing as “The Palestinian homeland”. Through out world history the names of countries have been changed many times because of war. The land of Canaan became Israel after Joshua subdued the land. Later 2 kingdoms came out of one, Israel and Juda, which the entire area was later called Judea during the time of Jesus. Not until the Romans changed the name did Israel become “Syria Palaestina”. However, today as it was known in the time of King David, the name of the country is Israel. The so called Palestinians do not have a country called Palestine."