Workers are organizing at unprecedented rates along

the border — in Mexico. Since January, thousands of factory workers

have been striking for higher wages in Mexican border cities, home to

hundreds of factories run by US companies and subcontractors

|

|

|

A man stands next to a Coca-Cola sign in Mexico City,

on December 2, 2015

credit: Marco Ugarte/AP // Vox |

Hundreds of Coca-Cola workers are camping out at a

major bottling plant until they get a raise. More than 8,000 Walmart

employees were prepared to walk off the job, until management met some

of their demands. And 30,000 striking factory workers have finally

returned to work after a month-long strike.

Workers are organizing at unprecedented rates along

the border — in Mexico.

Since January, thousands of factory workers have been

striking for higher wages in Mexican border cities, which are home to

hundreds of factories run by US companies and subcontractors. Factory

workers, who generally earn about $2.50 an hour, make car parts, washing

machines, appliances, and even soda for American consumers across the

border.Workers are angry with their employers for paying them poverty

wages, but they’re also upset with their labor unions, which are often

controlled by businesses and government officials. So far, union

officials have been unable to stop the strikes, which began in January

in Matamoros, an industrial border city that sits across the Rio Grande

from Brownsville, Texas.

The strikes have been so successful that they’ve

sparked what is now called the 20/32 Movement, based on the 20 percent

pay raise and 32,000 peso annual bonus (about $1,600) that striking

factory workers in the city initially demanded, and eventually won.

The movement is now spreading beyond factories in the

border region, with cashiers at US-owned supermarkets and fast-food

chains demanding raises too. That includes Sam’s Club stores and

Walmart stores.

The weeks-long strikes have caught business groups and

employers off guard. The Mexican government and labor unions have long

controlled the workforce with an iron grip, immediately quashing labor

unrest by jailing workers who go on strike. It’s just one of the

reasons why wages in Mexico remain among the lowest in the developed

world — a setup that US companies have encouraged.

But that’s all starting to change because of two

people: Mexico’s new populist president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador,

and US President Donald Trump. Despite their significantly different

stances on policy, both presidents share the view that Mexican labor

laws need a major overhaul to make free trade between both nations work.

And, somewhat ironically, it was López Obrador’s

recent decision to hike the minimum wage that triggered massive strikes.

Raising the minimum wage was unprecedented

In December, López Obrador fulfilled one of his

campaign promises: he raised the national minimum wage. The 16 percent

increase, which went into effect in January, raised the wage floor to

about 0.60 cents an hour. To be clear, that’s still a pretty bad rate.

AMLO simply raised the minimum to keep up with the cost of feeding a

family of four. The new minimum wage just ensures that people don’t

starve to death, and it’s certainly not enough for families to pay

rent or buy anything else, really.

But it was still seen as a major win for workers in

Mexico, who on average earn about $12.50 a day.

As part of this new policy, AMLO created a separate

minimum pay rate for workers in the border region, where about 2 million

people work in factories, or maquilas, owned by multinational

corporations. The new minimum wage in border states is about $1.1 an

hour —double what it was before. To help offset the cost to employers,

AMLO included a tax cut for businesses along the border.

But here’s the thing: Factory workers in cities like

Matamoros were already earning about $2.50 an hour, so the change didn’t

benefit them at all. They, too, insisted on getting a raise along with

minimum-wage earners, and many of their labor contracts actually

stipulated that they would get raises and bonuses based on changes to

the minimum wage. Which meant that their salaries should have doubled to

about $5 an hour because the minimum wage had doubled.

But the maquiladora industry in Matamoros, and the Day

Laborers, Industrial Workers, and Maquila Industries Union, which

represents most factory workers in the city, said such a wage hike was

too much. So two weeks after the new wage laws went into effect, on

January 1, about 30,000 workers went on strike. Their demand: a 20

percent raise and a 32,000-peso (about $1,600) bonus.

Business groups were outraged. The Mexican Employers

Federation called it a “crisis.” The local chamber of commerce said

the city would lose 20,000 jobs. Factories threatened to close. Workers

blocked access to their work sites, essentially shutting down 45

factories for several weeks.

By February 9, something unexpected had happened:

Managers at 45 factories agreed to employees’ demands, and their

30,000 employees got the raises and bonuses they asked for. At least two

factories, including a Chinese automaker, decided to move elsewhere, and

fired 1,500 people.

That didn’t discourage workers. In fact, strikes

have started to spread to other Mexican border states, including

Coahuila; Reynosa, Tamaulipas; Agua Prieta, and Sonora.

Coca-Cola workers are still striking. Walmart barely

avoided a work stoppage. Hundreds of workers at one of Coca-Cola’s largest

bottling and distribution plants have refused to go to work for almost

two months, demanding the same 20 percent increase with a $32,000 peso

bonus. Many have been camped outside the facility in Matamoros, blocking

strikebreakers from entering and bringing production nearly to a halt.

The Coca-Cola bottling plant, Arca Continental, is one

of the few employers in the state of Tamaulipas that have not agreed to

workers’ demands.

On Tuesday, employees put on their uniforms and

gathered outside the sprawling facility to continue the strike. Some had

slept on mattresses on the sidewalk, according to video posted online by

Susana Prieto Terrazas, a labor lawyer who is helping organize the

strikes.

“We’re going to stay here as long as we need to,”

said one of the workers standing outside.Their homemade signs accused the company of taking

advantage of them. “If they punch one of us, they punch all of us,”

read one of the signs.

A spokesperson for Coca-Cola in Mexico told me that

the company agrees with the way the Arca Continental, which runs the

bottling plant, is handling the strike, but didn’t say whether or not

Coca-Cola supports the workers’ demands.

“We are closely following the evolution of the

situation, and we trust that it will be solved as soon as possible,

always seeking for the welfare of our collaborators,” Lorena

Villarreal Clausell, communications director for Coca-Cola Mexico, wrote

in a statement to Vox.

While factory workers have been at the forefront of

the labor unrest, frustration has started to spread. In February, a

labor union representing 8,000 Walmart and Sam’s Club employees said

they would go on strike unless the company agreed to the 20/32 demands.

Workers complained that Walmart made them work long

hours and didn’t pay them overtime as required by law. They also

accused managers of discriminating against pregnant women, and not

enrolling some workers in their health insurance and retirement

programs, according to the Revolutionary Confederation of Laborers and

Farmworkers union, which represents employees at about 180 Walmart and

Sams Club stores in 10 states in Mexico.

“We, the workers of Walmart, have started a movement

to reclaim our rights,” the union stated in a video announcing the

strike earlier this month. “We’re fighting for better salaries, a

percentage of sales, to prevent layoffs and for the respect of human

rights.”

That includes janitors, cashiers, pharmacy clerks, and

warehouse workers. Last year, workers at Walmart stores across Mexico

earned between $4.81 and $8.83 a day, according to Reuters.

Watch video here.

The strike was set to begin last week, but the company

reached an agreement with the union at the last minute. They would give

employees a 5.5 percent raise and a productivity bonus — far less than

they asked for, but enough to avoid a strike. The relative success of these strikes has a lot to do

with politics.

López Obrador’s administration is not cracking down

on workers

Mexico’s new president and other members of his

populist Morena party have political control in Mexico right now, after

taking both chambers of Mexico’s Congress for the first time this

year. In the past, employers could count on the federal and state

government to intervene in labor strikes, which often led to brutal

crackdowns on workers. Unions rarely sided with the workers they are

supposed to represent.

But López Obrador and his allies in Congress are

making it a point to remain neutral. They have been encouraging

negotiations, but so far have refused to take punitive action against

workers.

“The businesses class also needs to take direct

responsibility for this, they need to be more socially responsible

toward workers, with the communities where they operate and with the

environment,” said Sen. Napoleón Gómez Urrutia, during a press

conference last week, according to El Milenio newspaper. “This is part

of our national politics and the new union movement we are promoting,

there has to be economic justice for there to be a peaceful labor

environment.”

The administration’s pro-labor policies will

inadvertently help an unlikely ally: President Donald Trump.

Mexico must pass new labor laws for the trade deal to

go into effect. In November, President Donald Trump announced that he

had accomplished one of his campaign promises: he had reached a deal

with Canada and Mexico to replace the North American Free Trade

Agreement, or NAFTA.

Under the new deal, known as the USMCA, Mexico has

promised to pass laws that will guarantee workers the right to form

unions and negotiate their own labor contracts.

Right now, workers in Mexico have the right to

unionize, but they are often left out of the negotiating process. US

manufacturers — and most other companies — end up dictating the

terms of the contract with labor unions to their own benefit, without

any input or approval from employees. Workers have also reported

retaliation from employers when they try to create a labor union.

Trump still needs Congress to ratify the pact, which

will likely face some resistance from House Democrats. Mexico and Canada

will also need to get their lawmakers on board. Trump had repeatedly railed against NAFTA for

decimating the US manufacturing industry.

When the trade pact was enacted in 1994, labor unions

worried at the time that allowing goods to cross the border untaxed

would give US manufacturers too much incentive to move factories and

jobs to Mexico, where wages were very low and environmental standards

more relaxed.

Proponents of NAFTA pushed back against that idea,

saying that boosting trade would raise wages for low-skilled Mexican

workers, pulling millions out of poverty and making it less attractive

for companies to move factories to Mexico.

But that definitely didn’t happen. Competition from

US farms was largely responsible for putting more than 1 million

farmworkers in Mexico out of work, and the unemployment rate in Mexico

is higher today than it was back then. On top of that, wages for workers in Mexico have

hardly budged.

The labor reforms in the new deal are supposed to

increase wages for Mexican workers, to give US companies less of an

incentive to move manufacturing jobs south of the border.

Aside from giving workers a voice in collective

bargaining, the USMCA would also require Mexico to pass a law extending

labor protections to migrant workers, many of whom come from Central

America and are vulnerable to exploitation.

The “new NAFTA” would allow the United States, for

example, to file labor complaints through the regular dispute resolution

system, but only if it involves labor violations that are harming US

trade. They can bring the complaint before a commission of government

labor ministers from each country, but only after exhausting all efforts

to mediate the issue and resolve it separately.

It seems like a long, painful process that could take

months to complete. But it’s better than the nonexistent process to

deal with labor violations under NAFTA. And it would require each

country to take an aggressive, hands-on enforcement approach.

The most challenging part will be enforcing a specific

provision in USMCA that mandates that 40 to 45 percent of a car’s

parts must be made by workers who earn at least $16 an hour to avoid

tariffs. That means that many Mexican factories that make parts for US

car manufacturers would have to pay eight times what they currently pay

the average factory worker. Or auto manufacturers would simply need to

buy more car parts made in the United States, where wages for factory

workers are much higher.

The trade deal does not mention how the US government

would even know what companies across the border are paying their

workers. It’s not clear how the Mexican government would know, either.

But López Obrador is making some changes that align with USMCA, and

lawmakers are expected to introduce the rest of the required proposals

this spring.

As a populist president whose political party now

controls both chambers of Mexico’s Congress, it shouldn’t be hard

for López Obrador to pass those reforms. Until then, the current labor

unrest in Mexico will likely continue to spread.

[Alexia Fernández Campbell is Vox Politics &

Policy Reporter.]

|

Like

many songwriters, Berlin saved every scrap of paper with every new song or

partial song he composed. As was his habit, he'd put the scraps of songs

in a trunk for possible use at a later date. So it was with "God

Bless America." He dug into his trunk to find the song

that changed America...

Like

many songwriters, Berlin saved every scrap of paper with every new song or

partial song he composed. As was his habit, he'd put the scraps of songs

in a trunk for possible use at a later date. So it was with "God

Bless America." He dug into his trunk to find the song

that changed America...

Tawn's reaction to an African-American man was totally

different. At about 15 months, she was walking well; however,

while shopping I usually held her hand. We were walking in downtown Inglewood. Suddenly she stopped, made some excited sounds and

acted as if she recognized someone she obviously dearly loved. She started

pulling me, and when she could not move me, she started twisting her

hand to pull away.

Tawn's reaction to an African-American man was totally

different. At about 15 months, she was walking well; however,

while shopping I usually held her hand. We were walking in downtown Inglewood. Suddenly she stopped, made some excited sounds and

acted as if she recognized someone she obviously dearly loved. She started

pulling me, and when she could not move me, she started twisting her

hand to pull away.

As

a college summer job, my daughter Tawn had the fun responsibility of

caring for baby Bengal tigers at the Japanese Village and Deer Park in

Buena Park, CA. Tawn's day started at 6:30 am. When she

arrived, three tiger mom's had each given birth to one cub. Soon

to be born were five cubs to one tigress. Tawn's responsibilities

with the older cubs, besides feeding them a special formulas, included

playing with them and taking them for early morning walks. The

three cubs would follow her, as cubs would ordinarily follow their

mother, strengthening their wobbly legs. The walkway which the

cubs used was the walkway used by all the animals. Deer, camels,

elephants, ostriches, and other animals, all used the walkway for exercising before

the doors open for visitors. The cubs then spent the day in the

petting zoo.

As

a college summer job, my daughter Tawn had the fun responsibility of

caring for baby Bengal tigers at the Japanese Village and Deer Park in

Buena Park, CA. Tawn's day started at 6:30 am. When she

arrived, three tiger mom's had each given birth to one cub. Soon

to be born were five cubs to one tigress. Tawn's responsibilities

with the older cubs, besides feeding them a special formulas, included

playing with them and taking them for early morning walks. The

three cubs would follow her, as cubs would ordinarily follow their

mother, strengthening their wobbly legs. The walkway which the

cubs used was the walkway used by all the animals. Deer, camels,

elephants, ostriches, and other animals, all used the walkway for exercising before

the doors open for visitors. The cubs then spent the day in the

petting zoo.

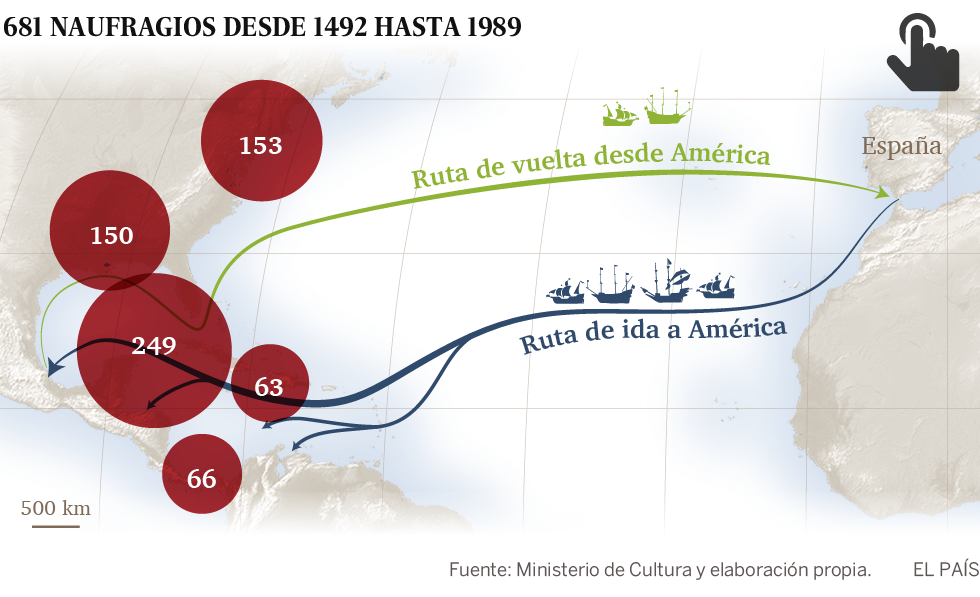

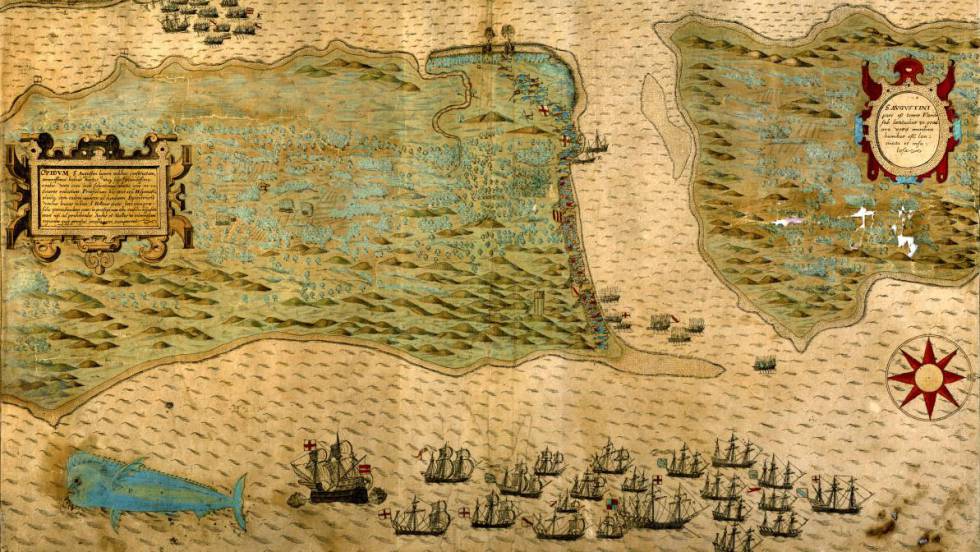

Sin embargo, este personaje de Robert Louis

Stevenson no tendría vidas suficientes para saquear los 681 navíos

que el primer Inventario de naufragios españoles en América,

redactado por la Subdirección General de Patrimonio Histórico del

Ministerio de Cultura y que hoy revela EL PAÍS, documenta. Tendría

en su poder, eso sí, la historia de España entre 1492 y 1898,

información que ha coordinado el arqueólogo submarino Carlos León

con la colaboración de su colega Beatriz Domingo y la historiadora

naval Genoveva Enríquez.

Sin embargo, este personaje de Robert Louis

Stevenson no tendría vidas suficientes para saquear los 681 navíos

que el primer Inventario de naufragios españoles en América,

redactado por la Subdirección General de Patrimonio Histórico del

Ministerio de Cultura y que hoy revela EL PAÍS, documenta. Tendría

en su poder, eso sí, la historia de España entre 1492 y 1898,

información que ha coordinado el arqueólogo submarino Carlos León

con la colaboración de su colega Beatriz Domingo y la historiadora

naval Genoveva Enríquez.