The

following is adapted from a talk delivered on January 28, 2020, at

Hillsdale College’s Allan P. Kirby, Jr. Center for Constitutional

Studies and Citizenship in Washington, D.C., as part of the AWC

Family Foundation lecture series.

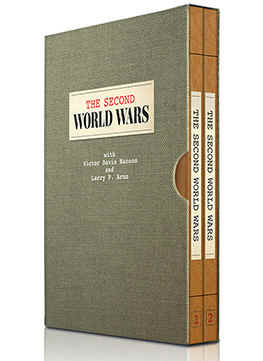

American

society today is divided by party and by ideology in a way it has

perhaps not been since the Civil War. I have just published a book

that, among other things, suggests why this is. It is called The

Age of Entitlement: America Since the Sixties. It runs from the

assassination of John F. Kennedy to the election of Donald J. Trump.

You can get a good idea of the drift of the narrative from its

chapter titles: 1963, Race, Sex, War, Debt, Diversity, Winners, and

Losers.

I

can end part of the suspense right now—Democrats are the winners.

Their party won the 1960s—they gained money, power, and

prestige. The GOP is the party of the people who lost those things.

One

of the strands of this story involves the Vietnam War. The

antiquated way the Army was mustered in the 1960s wound up creating

a class system. What I’m referring to here is the so-called

student deferment. In the old days, university-level education was

rare. At the start of the First World War, only one in 30 American

men was in a college or university, so student deferments were not

culturally significant. By the time of Vietnam, almost half of

American men were in a college or university, and student deferment

remained in effect until well into the war. So if you were rich

enough to study art history, you went to Woodstock and made love. If

you worked in a garage, you went to Da Nang and made war. This

produced a class division that many of the college-educated mistook

for a moral division, particularly once we lost the war. The rich

saw themselves as having avoided service in Vietnam not because they

were more privileged or—heaven forbid—less brave, but because

they were more decent.

Another

strand of the story involves women. Today, there are two cultures of

American womanhood—the culture of married women and the culture of

single women. If you poll them on political issues, they tend to

differ diametrically. It was feminism that produced this rupture.

For women during the Kennedy administration, by contrast, there was

one culture of femininity, and it united women from cradle to grave:

Ninety percent of married women and 87 percent of unmarried women

believed there was such a thing as “women’s intuition.” Only

16 percent of married women and only 15 percent of unmarried women

thought it was excusable in some circumstances to have an

extramarital affair. Ninety-nine percent of women, when asked the

ideal age for marriage, said it was sometime before age 27. None

answered “never.”

But

it is a third strand of the story, running all the way down to our

day, that is most important for explaining our partisan

polarization. It concerns how the civil rights laws of the 1960s,

and particularly the Civil Rights Act of 1964, divided the country.

They did so by giving birth to what was, in effect, a second

constitution, which would eventually cause Americans to peel off

into two different and incompatible constitutional cultures. This

became obvious only over time. It happened so slowly that many

people did not notice.

Because

conventional wisdom today holds that the Civil Rights Act brought

the country together, my book’s suggestion that it pulled the

country apart has been met with outrage. The outrage has been

especially pronounced among those who have not read the book. So for

their benefit I should make crystal clear that my book is not

a defense of segregation or Jim Crow, and that when I criticize the

long-term effects of the civil rights laws of the 1960s, I do not

criticize the principle of equality in general, or the movement for

black equality in particular.

What

I am talking about are the emergency mechanisms that, in the name of

ending segregation, were established under the Civil Rights Act of

1964. These gave Washington the authority to override what Americans

had traditionally thought of as their ordinary democratic

institutions. It was widely assumed that the emergency mechanisms

would be temporary and narrowly focused. But they soon escaped

democratic control altogether, and they have now become the most

powerful part of our governing system.

How

Civil Rights Legislation Worked

There

were two noteworthy things about the civil rights legislation of

1964 and 1965.

The first was its

unprecedented concentration of power. It gave Washington tools it

had never before had in peacetime. It created new crimes, outlawing

discrimination in almost every walk of public and private life. It

revoked—or repealed—the prevailing understanding of freedom of

association as protected by the First Amendment. It established

agencies to hunt down these new crimes—an expanded Civil Rights

Commission, an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), and

various offices of civil rights in the different cabinet agencies.

It gave government new prerogatives, such as laying out hiring

practices for all companies with more than 15 employees, filing

lawsuits, conducting investigations, and ordering redress. Above

all, it exposed every corner of American social, economic, and

political life to direction from bureaucrats and judges.

To

put it bluntly, the effect of these civil rights laws was to take a

lot of decisions that had been made in the democratic parts of

American government and relocate them to the bureaucracy or the

judiciary. Only with that kind of arsenal, Lyndon Johnson and the

drafters thought, would it be possible to root out insidious racism.

The

second noteworthy thing about the civil rights legislation of the

1960s is that it was kind of a fudge. It sat uneasily not only with

the First Amendment, but with the Constitution as a whole. The

Voting Rights Act of 1965, passed largely to give teeth to the 14th

Amendment’s guarantee of equal rights for all citizens, did so by

creating different levels of rights for citizens of southern states

like Alabama and citizens of northern states like Michigan when it

came to election laws.

The goal of the civil rights

laws was to bring the sham democracies of the American South into

conformity with the Constitution. But nobody’s democracy is

perfect, and it turned out to be much harder than anticipated to

distinguish between democracy in the South and democracy elsewhere

in the country. If the spirit of the law was to humiliate Southern

bigots, the letter of the law put the entire country—all its

institutions—under the threat of lawsuits and prosecutions for

discrimination.

Still, no one was too worried

about that. It is clear in retrospect that Americans outside the

South understood segregation as a regional problem. As far as we can

tell from polls, 70-90 percent of Americans outside the South

thought that blacks in their part of the country were treated just

fine, the same as anyone else. In practice, non-Southerners did not

expect the new laws to be turned back on themselves.

The

Broadening of Civil Rights

The problem is that when the

work of the civil rights legislation was done—when de jure

segregation was stopped—these new powers were not suspended or

scaled back or reassessed. On the contrary, they intensified. The

ability to set racial quotas for public schools was not in the

original Civil Rights Act, but offices of civil rights started doing

it, and there was no one strong enough to resist. Busing of

schoolchildren had not been in the original plan, either, but once

schools started to fall short of targets established by the

bureaucracy, judges ordered it.

Affirmative

action was a vague notion in the Civil Rights Act. But by the time

of the Supreme Court’s 1978 Bakke decision, it was an

outright system of racial preference for non-whites. In that case,

the plaintiff, Alan Bakke, who had been a U.S. Marine captain in

Vietnam, saw his application for medical school rejected, even

though his test scores were in the 96th, 94th, 97th, and 72nd

percentiles. Minority applicants, meanwhile, were admitted with, on

average, scores in the 34th, 30th, 37th, and 18th percentiles. And

although the Court decided that Bakke himself deserved admission, it

did not do away with the affirmative action programs that kept him

out. In fact, it institutionalized them, mandating

“diversity”—a new concept at the time—as the law of the

land.

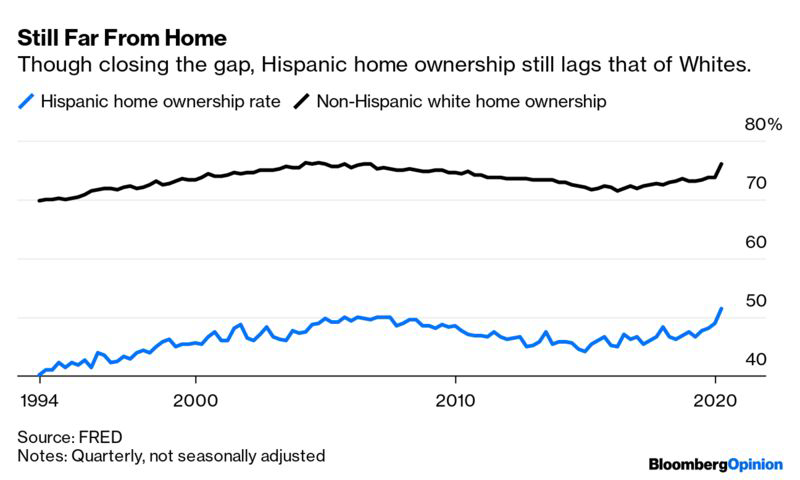

Meanwhile

other groups, many of them not even envisioned in the original

legislation, got the hang of using civil rights law. Immigrant

advocates, for instance: Americans never voted for bilingual

education, but when the Supreme Court upheld the idea in 1974, rule

writers in the offices of civil rights simply established it, and it

exists to this day. Women, too: the EEOC battled Sears, Roebuck

& Co. from 1973 to 1986 with every weapon at its disposal,

trying to prove it guilty of sexism—ultimately failing to prove

even a single instance of it.

Finally,

civil rights came to dominate—and even overrule—legislation that

had nothing to do with it. The most traumatic example of this was

the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. This legislation was

supposed to be the grand compromise on which our modern immigration

policy would be built. On the one hand, about three million illegal

immigrants who had mostly come north from Mexico would be given

citizenship. On the other hand, draconian laws would ensure that the

amnesty would not be an incentive to future migrants, and that

illegal immigration would never get out of control again. So there

were harsh “employer sanctions” for anyone who hired a

non-citizen. But once the law passed, what happened? Illegal

immigrants got their amnesty. But the penalties on illegal hiring

turned out to be fake—because, to simplify just a bit, asking an

employee who “looks Mexican” where he was born or about his

citizenship status was held to be a violation of his civil rights.

Civil rights law had made it impossible for Americans to get what

they’d voted for through their representatives, leading to decades

of political strife over immigration policy that continues to this

day.

A

more recent manifestation of the broadening of civil rights laws is

the “Dear Colleague” letter sent by the Obama Education

Department’s Office for Civil Rights in 2011, which sought to

dictate sexual harassment policy to every college and university in

the country. Another is the overturning by judges of a temporary ban

on entry from certain countries linked to terrorism in the first

months of the Trump administration in 2017.

These

policies, qua policies, have their defenders and their

detractors. The important thing for our purposes is how they were

established and enforced. More and more areas of American life have

been withdrawn from voters’ democratic control and delivered up to

the bureaucratic and judicial emergency mechanisms of civil rights

law. Civil rights law has become a second constitution, with powers

that can be used to override the Constitution of 1787.

The

New Constitution

In

explaining the constitutional order that we see today, I’d like to

focus on just two of its characteristics.

First,

it has a moral element, almost a metaphysical element, that

is usually more typical of theocracies than of secular republics. As

we’ve discussed, civil rights law gave bureaucrats and judges

emergency powers to override the normal constitutional order,

bypassing democracy. But the key question is: Under what conditions

is the government authorized to activate these emergency powers? It

is a question that has been much studied by political thinkers in

Europe. Usually when European governments of the past bypassed their

constitutions by declaring emergencies, it was on the grounds of a

military threat or a threat to public order. But in America, as our

way of governing has evolved since 1964, emergencies are declared on

a moral basis: people are suffering; their newly discovered rights

are being denied. America can’t wait anymore for the ordinary

democratic process to take its course.

A

moral ground for invoking emergencies sounds more humane than a

military one. It is not. That is because, in order to justify its

special powers, the government must create a class of officially

designated malefactors. With the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the

justification of this strong medicine was that there was a

collection of Southern politicians who were so wily and devious, and

a collection of Southern sheriffs so ruthless and depraved, that one

could not, and was not morally obliged to, fight fair with them.

That

pattern has perpetuated itself, even as the focus of civil rights

has moved to American institutions less obviously objectionable than

segregation. Every intervention in the name of rights requires the

identification of a malefactor. So very early on in the gay marriage

debate, those who believed in traditional marriage were likened to

segregationists or to those who had opposed interracial marriage.

Joe

Biden recently said: “Let’s be clear: Transgender equality is

the civil rights issue of our time. There is no room for compromise

when it comes to basic human rights.” Now, most Americans,

probably including Joe Biden, know very little about transgenderism.

But this is an assertion that Americans are not going to be

permitted to advance their knowledge by discussing the issue in

public or to work out their differences at the ballot box. As civil

rights laws have been extended by analogy into other areas of

American life, the imputation of moral non-personhood has been aimed

at a growing number of people who have committed no sin more

grievous than believing the same things they did two years ago, and

therefore standing in the way of the progressive juggernaut.

The

second characteristic of the new civil rights constitution is what

we can call intersectionality. This is a sociological

development. As long as civil rights law was limited to protecting

the rights of Southern blacks, it was a stable system. It had the

logic of history behind it, which both justified and focused its

application. But if other groups could be given the privilege of

advancing their causes by bureaucratic fiat and judicial decree,

there was the possibility of a gradual building up of vast new

coalitions, maybe even electoral majorities. This was made possible

because almost anyone who was not a white heterosexual male could

benefit from civil rights law in some way.

Seventy

years ago, India produced the first modern minority-rights based

constitution with a long, enumerated list of so-called “scheduled

tribes and castes.” Eventually, inter-group horse trading took up

so much of the country’s attention that there emerged a grumbling

group of “everyone else,” of “ordinary Indians.” These

account for many of the people behind the present prime minister,

Narendra Modi. Indians who like Modi say he’s the candidate of

average citizens. Those who don’t like him, as most of the

international media do not, call him a “Hindu nationalist.”

We

have a version of the same thing happening in America. By the

mid-1980s, the “intersectional” coalition of civil rights

activists started using the term “people of color” to describe

itself. Now, logically, if there really is such a thing as “people

of color,” and if they are demanding a larger share of society’s

rewards, they are ipso facto demanding that “non–people

of color” get a smaller share. In the same way that the Indian

constitution called forth the idea of a generic “Hindu,” the new

civil rights constitution created a group of “non–people of

color.” It made white people a political reality in the United

States in a way they had never been.

Now

we can apply this insight to parties. So overpowering is the

hegemony of the civil rights constitution of 1964 over the

Constitution of 1787, that the country naturally sorts itself into a

party of those who have benefitted by it and a party of those who

have been harmed by it.

A

Party of Bigots and a Party of Totalitarians

Let’s

say you’re a progressive. In fact, let’s say you are a

progressive gay man in a gay marriage, with two adopted children.

The civil rights version of the country is everything to you. Your

whole way of life depends on it. How can you back a party or a

politician who even wavers on it? Quite likely, your whole moral

idea of yourself depends on it, too. You may have marched in gay

pride parades carrying signs reading “Stop the Hate,” and you

believe that people who opposed the campaign that made possible your

way of life, your marriage, and your children, can only have done so

for terrible reasons. You are on the side of the glorious

marchers of Birmingham, and they are on the side of Bull

Connor. To you, the other party is a party of bigots.

But

say you’re a conservative person who goes to church, and your

seven-year-old son is being taught about “gender fluidity” in

first grade. There is no avenue for you to complain about this.

You’ll be called a bigot at the very least. In fact, although

you’re not a lawyer, you have a vague sense that you might get

fired from your job, or fined, or that something else bad will

happen. You also feel that this business has something to do with

gay rights. “Sorry,” you ask, “when did I vote for this?”

You begin to suspect that taking your voice away from you and taking

your vote away from you is the main goal of these rights movements.

To you, the other party is a party of totalitarians.

And that’s our current party

system: the bigots versus the totalitarians.

If either of these

constitutions were totally devoid of merit, we wouldn’t have a

problem. We could be confident that the wiser of the two would win

out in the end. But each of our two constitutions contains, for its

adherents, a great deal worth defending to the bitter end. And

unfortunately, each constitution must increasingly defend itself

against the other.

When gay marriage was being

advanced over the past 20 years, one of the common sayings of

activists was: “The sky didn’t fall.” People would say:

“Look, we’ve had gay marriage in Massachusetts for three weeks,

and I’ve got news for you! The sky didn’t fall!” They were

right in the short term. But I think they forgot how delicate a

system a democratic constitutional republic is, how difficult it is

to get the formula right, and how hard it is to see when a

government begins—slowly, very slowly—to veer off course in a

way that can take decades to become evident.

Then one day we discover that,

although we still deny the sky is falling, we do so with a lot less

confidence.

This message may contain copyrighted material which is being made

available for research of environmental, political, human rights,

economic, scientific, social justice issues, etc., and constitutes

a "fair use" of such copyrighted material per section

107 of US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C.

Section 107, the material in this message is distributed without

profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior interest in

receiving it for research/educational purposes. For more

information go to:

http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

Alexandra

Oliver-Dávila is a BPS parent. For more than 20 years, Alex has

worked to create a community that supports Latino youth, values

their input, and believes in their ability to create positive

social change. Serving as Executive Director since 1999, Alex

has transformed Sociedad Latina into a cutting-edge,

data-driven, creative youth development organization. Under her

leadership, Sociedad Latina has increased and diversified its

budget, expanded board membership, increased the number of youth

and families it works with and expanded programming.

Alexandra

Oliver-Dávila is a BPS parent. For more than 20 years, Alex has

worked to create a community that supports Latino youth, values

their input, and believes in their ability to create positive

social change. Serving as Executive Director since 1999, Alex

has transformed Sociedad Latina into a cutting-edge,

data-driven, creative youth development organization. Under her

leadership, Sociedad Latina has increased and diversified its

budget, expanded board membership, increased the number of youth

and families it works with and expanded programming.

Throughout

our nation’s history, brave men and women have fought to secure

and preserve American liberty. It is an incredible history. One that

we must understand and pass on to the next generation of Americans.

Throughout

our nation’s history, brave men and women have fought to secure

and preserve American liberty. It is an incredible history. One that

we must understand and pass on to the next generation of Americans.