|

Chapter Thirteen Spanish Resettlement of Nuevo Méjico 1692 C.E.-1800 C.E.

When most Anglo-American, Northern European, and

non-Spanish historians and commentators write about Nueva España, España, and Españoles

or Spaniards they offer only the most obvious of circumstances. The

commentaries and conclusions drawn are normally offered without the

reasons for governmental actions in the Nuevo

Mundo. The undercurrent

that they inevitably stress for actions taken by the Españoles

is almost always the Black Legend and its relentless attack upon the

Noble Savage. These

represent their superimposed world view of España’s

conduct in her dominions. This

underpinning is served up in concert with the inevitable

characterization of the Españoles

as Conquistadores or conquerors first, followed by their being greedy,

cruel, and bloodthirsty. However, I must say that there are several

non-Spanish writers, commentators, and historians that I can think of as

fair minded and accurate. I

should say at the outset that both the Daughters of the American

Revolution and the Sons of the American Revolution have taken a highly

ethical and honorable position on España

and its subjects during the American Revolution, citing the many

kindnesses and assistance given by España

to the American Revolution. Another

is Judge Edward Butler who wrote the book “Gálvez.”

A second and third are Granville W. Hough a retired Lieutenant

Colonel, amateur genealogist, and

historian for forty-five years and his daughter, N. C. Hough.

These in particular are to be commended for their honesty and

love of the truth as it relates to España

and Españoles. Let me clarify, I’m not a historian.

My interest is the legacy of my progenitors, the Españoles

and my family, the de Ribera. They

have been misrepresented by those parties which choose to continue in

the mischaracterization of the Españoles and España.

Thus, undertaken in this family history is an effort to clarify

the state of affairs of Nueva España

and Nuevo Méjico during the period covered in this chapter in which my

family lines were participants. Also, a need exists to once again clarify the

complexity of España’s

governance of the Nuevo Mundo, Nueva España, and Nuevo

Méjico. That is to say,

at any given point in time during the Nuevo

Méjico Spanish Period (1598 C.E.-1821 C.E.) governance was

dependent upon political, religious, military, and economic

circumstances in the Viejo Mundo

or Old World and on the ground in the Nuevo Mundo. In

addition, conditions in Nueva España

and Nuevo Méjico were in a constant state of flux and transition due

many times to circumstances beyond the control of those Españoles in the Nuevo Mundo. One important aspect of this includes the fact

that España continually

underwent political and economic changes which impacted its Nuevo Mundo adversely.

Her initial Iberian Peninsula monarchy, that of Fernando II de Aragón

of the House of Trastámara the Kingdom of Aragón and Ysabel I,

the daughter of John II of Castilla

and Isabella of Portugal the

Queen of Castilla, was short-lived. An Austrian

monarchy, the House of Hapsburg, replaced it in the very

early-1500s C.E. And

finally, a French monarchy, the Borbóns,

of the early-1700s C.E. replaced it. The second and third monarchies were decidedly

expansionist and meddlesome as it relates to Europe.

This led to constant wars and the misuse of treasure which

further undermined her ability to govern the Nuevo

Mundo efficiently and effectively.

However, these factors do not make España

a totally corrupt entity bent only upon conquest and destruction of

Native peoples as anti-Spanish writers and commentators would have us

believe. Propaganda isn’t

always correct. The information provided by these

anti-Spanish sources especially that which is obviously of a biased or

misleading nature, has been used to promote Britain and the United

States over España. The

best offense is a great defense and all of that.

To benefit themselves, they publicized their particular political

causes and/or points of view. Therefore

these must be challenged intellectually. Additionally, as I’ve stated before, leading

Spanish historical figures were and are almost always served up by

anti-Spanish historians and commentators as cardboard figures. These

are presented as caricatures devoid of personal background and humanity

and given the label “Conquistador” or conqueror. What

this approach suggests is an ongoing ignorance of the facts and

conditions. It also does a

disservice to the many Spanish historical figures that played an

important part in Nueva España. The resulting logic tree is that these Conquistadores

after imposing their will upon the conquered only took what they wanted,

offering nothing of value to the region.

This is followed inevitably by the idea of unwanted colonization,

that position taken by one of the warring parties, the Natives.

According to the anti-Spanish historians and commentators, the Españoles never settled, but always colonized.

Therefore, they cannot be pobladores,

or settlers or Ciudádanos, or

citizens. The inevitable

result is that the Españoles

can only be seen as colonists. This

leads the reader to only one conclusion; the Españoles

were somehow illegitimate squatters.

If they were only squatters, whatever they did was of no

consequence. It would then

follow that because of the resulting illegitimacy of their colonial

presence in the Nuevo Mundo they had no

legal standing. Therefore,

before we can proceed with the story of my family, we must begin at the

beginning in order to clarify the reality of Spanish settlement. Let us begin with an important premise. The

España that these

anti-Spanish historians and commentators described did not exist.

They were not simply one people whose psyche was formed by the

almost 800 year Spanish “Reconquista” or Reconquest of Iberia and the removal of the Moros

or Moors. My statement is

based upon the proposition that España

was a place and people that continued to transition from its Iberian

inception in 1492 C.E. through its fall as a world empire after 1899

C.E., when it sold its last Pacific Islands.

España was not an Iberian monarchy for long, only 14 years.

In fact, she became an Austrian oriented empire in 1506

C.E. which lasted until 1700 C.E., a period of almost 200 years.

Later, España became a

French oriented monarchy from 1700 C.E. through her fall from

power in 1899 C.E., or another 200 years. Firstly, prior to España’s beginning (1492 C.E.), the lands of the Iberian

Peninsula on which it is situated were inhabited by many peoples who had

arrived there and settled [Libyans, Celts, Israelites, Carthaginians,

Greeks, Romans, Germanic Tribes, Moros

(Moors), etc.] over thousands of years.

Therefore, these were not Españoles,

but tribes with their own world views, religions, cultures, and

governance. It should be

obvious that over the course of time and history these tribes remained

by and large separate groups. Few

if any traveled beyond their farm or village.

Therefore, not all led the Reconquista,

that tribe was the Germanic Visigoths who later would be called the

Kingdom of Castilla. The others

followed into battle when necessary. The Iberian tribes did not suddenly coalesce into Españoles

upon the defeat of the Moros

by the original Germanic Iberian (Spanish) kings of Aragón

and Castilla in 1492 C.E.

Instead, all parties went through a gradual evolution until

arriving at an accommodation vis-à-vis

being Españoles.

As a result, España was based upon the beliefs of many Iberian tribes who came

together as a loose group of tribes in the state of becoming Españoles. The guiding light of the newly minted España

was Ysabel I’s continental state of Castilla.

It was steeped in many centuries of Visigoth culture and history and dedicated

to the Reconquista and the

defeat of the Islamic Moros.

Aragón’s

contribution to the new España

was that of a kingdom which was a maritime power and had a close

association with France. The

transition of these Iberians to Españoles

only became a reality after España’s

headlong plunge into exploration and settlement of the Nuevo

Mundo. It was at that

point that the men from all of the Iberia tribes partook in the quest

and began melding into subjects of el

Imperio Español. Additionally, one must remember that the expanded

exploration and settlement of the Nuevo

Mundo began and ended with foreign monarchs (Austrian and French),

not the Iberians. What the

Anti-Spanish writers fail to understand is that in 1492 C.E. after the

defeat of the Moros and the fall of Granada,

there was no “one” España. Instead,

Iberia consisted of many Españas

governed by one Iberian monarchy. Therefore,

there could have been no unifying Spanish belief other than the religion

of Catholicism. To clarify, the United States of America of 1776

C.E. was a largely European (British) affair.

Its people, culture, religion, and history were driven by

European men. Today’s

America has a large percentage of minority (Non-European) citizens, its

half female, and is a melding of cultures and religious views.

Can America of the 18th-Century C.E. be seen as the America of

today? Are the people,

language, culture, religion, etc. the same?

The answer is simple. No!

How then could España

remain the same at any given point in time?

The answer, it couldn’t. To further compound this problem of Iberian

unification, the original Iberian, proto-Spanish kings of Aragón and Castilla only

began their control of the majority of the Peninsula in 1492 C.E, the

same year that Cristóbal

Colón or Columbus sailed to the Nuevo

Mundo. Additionally,

control of the newly minted España

would only last a short 14 years, until 1506 C.E.

This is a very limited time for creation and consolidation of a

new nation. These

transitioning Iberians on the verge of becoming Españoles

had fought a long, hard, and bitter struggle of 781 years against the

entrenched, obstinate, religiously fanatical Islamic

Moros for their freedom. They

had battled, bled, died, and finally beaten a powerful and implacable

enemy. However, they were

still separate tribes and not one large consolidated, coalesced Spanish

nation. By 1504 C.E., Queen Ysabel I of Castilla was

dead. After his wife’s

death, Fernando II of Aragón would try to maintain his position over Castilla, but the Castilian Cortés

Generales or the royal court of España

chose to crown Ysabel's

daughter, Joanna, as queen. Her

husband was Felipe I, a

Habsburg. He was the son of

the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I and Mary of Burgundy.

Felipe I was declared

king of España jure uxoris, serving "by right of (his) wife."

His title of nobility was held by him because his wife held it suo

jure, "in her own right."

Soon, Joanna began her journey into insanity.

Those of the old Germanic order of Castilla

being Iberians (Españoles)

understood the meaning of Iberia (España)

as she did. This was quite a

different meaning from those held by the House of Habsburg or House

of Austria. This Iberian

Raison d'être was to all be erased with the imposition of sovereign

of foreign extraction in 1506 C.E. who knew nothing of that reality.

After all, Austrians were not Iberians. Felipe I was eventually declared king, but died later under mysterious

circumstances. At the time, Felipe

and Joanna’s oldest son Carlos

(Charles Quint) was only six.

It has been suggested that Felipe

was possibly poisoned by his Iberian father-in-law, Fernando

II. The Cortés then reluctantly allowed Joanna's father, Fernando

II, to rule España as regent

of Joanna and young Carlos.

Here it must be remembered that this body had considerable power.

The Cortés Generales

or General Courts had already come about when a new social class started

to grow. People living in

the cities were neither vassals nor nobles.

The King began admitting representatives from the cities to the Cortés.

By the time of young Carlos,

the Cortés already had the

power to oppose the King's decisions, thus effectively vetoing them.

In addition, some representatives were permanent advisors to the

King, even when the Cortés was not. As happens, life sorts itself out and the

Habsburgs remained. While España’s

Habsburgs’ were only a part of that major branch of the Habsburg

Dynasty, they would be associated with the future history of greater

Europe and its issues of succession and power via what they saw as the

possibility of a new Roman Empire spanning Europe under the Habsburgs.

España which had begun under the Iberian kings was barely 14 years

old and still in its political and cultural infancy when she gradually

began her transition from a monarchy with power over Iberia to an

Imperial worldwide power. The

Habsburgs would rule España,

when Carlos reached majority from 1516 C.E. through 1700 C.E.

This period of España’s

history would last 184 years during the 16th-and 17th-centuries C.E.

The great Habsburg rulers would be chiefly Carlos

I and Felipe II. This period

of Spanish history would be referred to as the "Age of

Expansion." Forty-four years later, in 1560 C.E., there were

barely 20,000 Españoles in

that area of España’s

Nuevo Mundo called Nueva España.

The Native population was devastated in the early Spanish Period,

with an estimated 70 to 90 percent dying due to disease, famine, and

other factors. There were an

estimated 25 million before the conquest and a little over a million by

1605 C.E. Here, I must explain to those that seem bent upon

presenting España and her

people as willingly participants in a planned genocide, it is not so.

This was not a Spanish government sanctioned “Intelligence

Operation” housed at Madrid,

España.

They did not purposely plan, develop, and execute such actions as

disease pandemics in government laboratories, create vaccinations to

purposely infect the population with deadly diseases, use drug

medications, deadly chemotherapy and radiation prescribed by doctors, or

escalate routine diseases such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and

Parkinson’s to kill. Nor

did they deliberately design famines, implement weather

modification/control to deliberately produce droughts and floods in

food-growing areas to destroy the Native populations.

Rather, the devastation came about in the main by human contact

and diseases. These found

undefended human populations in which to grow, make ill, and eventually

kill. Now that I’ve

belabored the issue, let’s move on. During this period, Spanish imperial expansion

reached its zenith of influence, power, and control of territory

including the Américas, the

East Indies, the Low Countries and territories (now in France and

Germany in Europe), the Portuguese Empire (1580 C.E.-1640 C.E.), and

other territories such as Ceuta

and Oran in North Africa. Under the Habsburgs, España dominated Europe politically and militarily through much of

the Age of Expansion. It

achieved this by spending much of the Empire’s wealth in Europe and

neglecting its Spanish Nuevo Mundo.

However, it would experience a gradual decline of influence under

the later Habsburg kings in the second half of the 17-Century C.E.

After these any, many years, in 1700 C.E. the Austrian Habsburg

kings would be followed by a new foreign monarchy, the French Borbón

kings. During the early-18th-Century C.E., the Spanish Borbón

kings (Cousins of the French Bourbons) arrived on the Spanish throne. Immediately

upon assuming the throne the Borbón

Monarchy wanted complete control over the governance of their worldwide

empire. They arrived only to

find the governing machinery of España

cumbersome and ill suited for the new century.

It was clear to all that the policies of the last Austrian

Hapsburg kings had failed. Here, we must make clear that the first Borbón

monarch, Felipe V (1700 C.E.-1746 C.E.) and his son Carlos III (1759 C.E.-1788 C.E.) were dedicated to implementing new

methods of governing. These

were based upon the French model of governance inspired by the ideals of

Enlightenment. However, this

was not the only need of the French.

The Austrian Hapsburgs via España

and her wealth had been in an ongoing feud with France over control of

Europe. The Austrians had

used the wealth of España to

blunt France’s aspirations at every turn.

Now the shoe was on the other foot, as it were. What the

Borbón monarch faced was entrenched traditionalism.

The new Corona Española's

insistence would overcome these impediments and bring España

again to a status of world power of the first order.

But she would be opposed. That

opposition would come from France and Britain.

By the 18th and 19th centuries

C.E., the Spanish government would become concerned with the fact that

the northern frontier provinces of Nueva

España were under populated and thus vulnerable to foreign invasion

and occupation. This concern

was particularly important in its impact on the settlement of Tejas, Arizona, and Alta

California thought to be most vulnerable to foreign invasion.

As a result, the Corona Española would find it necessary, if not essential, to

marshal its secular and religious resources to settle these areas

quickly and prepare to protect them.

The Españoles had

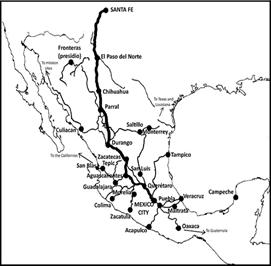

already blazed a trail from Méjico

City northward to Santa Fé, Nuevo Méjico via its Camino

Real. The trail would be

extended from the most northern point of the Camino

outward as España expanded

her holdings. Here, let me add another major

point to this discussion. For

some strange reason many people I speak to view España

as an exclusively Iberian, monolithic, homogeneous empire from 1492 C.E.

through its growth and demise. To

the contrary, it had over the course of centuries in fact become a

worldwide, multi-national, multi-ethnic, and multi-cultural entity. Given

this reality, it should be noted that to the degree possible, España

was inclusive of all its peoples. Peoples

throughout the Empire saw themselves as part of her.

As the Iberian Españoles

intermingled with others, these became part of the Imperio Español. It

would be of some value for the reader to begin to see España as an empire made up of many places, peoples, and cultures. This is no different than the

United States with its Pax Americana of our day. Her

citizens are African-American, Asian-American, Hispanic-American,

Native-American, European-American all being part of the greater nation

and union. In this context

the term Españoles takes on a

larger more complex meaning. Filipinos,

Pacific and Caribbean islanders, some in European non-Iberian nations,

and others saw themselves as part of the Empire.

So too, did those in Nueva España.

This happened not only through the government, but the Church,

and intermarriage. By this logic, I’m not

suggesting that the right of kings had been done away with or the rights

of the average man had increased in el

Imperio Español. What I

am saying is that given the cultural values of the time and the

governance of each land, nation states had their own unique set of

variables which drove day-to-day life.

Given the religious, political, and cultural conditions of the

time, each person operated under obvious constraints.

To put European and Spanish society in the context of the

freedoms of the 21st-Century C.E., with its citizen’s rights and

racial equality would be a mistake.

Instead, one must accept history for what it is. It

is simply a view of a given point in time with religious, economic,

social, governance, and political conditions as they existed then. The Spanish authorities in Nueva

España enjoyed the patronato

real or royal patronage over ecclesiastical affairs, granted to the Corona

Española by the Catholic Pope.

Based upon the

Spanish “New Laws” issued in the 1540s C.E., instructions from the

Spanish government were given as to which misiónes

were to be founded. This

policy was made to establish Spanish control of the land by teaching

Catholicism to the Natives. It

was hoped that this would eventually cause the Natives then to become

Spanish Ciudádanos. According

to the plan, they would be the pobladores

or settlers of the new forward areas of North America.

It was believed that this was the quickest way of founding

Spanish (Expanded view) villas

in such remote areas rather than moving large numbers of

racially/ethnically Iberian and other European pobladores

there from España or southern

Nueva España. It was a wise

choice given the fact that well-established communities did not want to

be relocated to such remote areas. The code of the Spanish New Laws issued early on

in the 1540s C.E. stated that (1) Natives should be permitted to dwell

in communities of their own, (2) They should be permitted to choose

their own leaders and councilors, (3) No Native might be held as a

slave, (4) No Native might live outside his own village nor might any

Spanish lay-person dwell within a Native village for longer than 3 days

and then only if he were a merchant, (5) Natives were to be instructed

in the Catholic faith. This

suggests a maturing of Spanish mind and heart as it relates to their

fellow man (New World Natives). The Spanish misión or mission system was that frontier institution which sought

to incorporate Natives into the Imperio

Español and its Catholic Church.

It was the Franciscans from several of Nueva

España’s provincias or

provinces and misiónero or

missionary colleges that would establish these misiónes

or missions. Further, the

system would ensure their tutelage by misióneros.

However, the Monarchy as patrons, would make final determinations

as to where and when misiónes

would be established or closed, what administrative policies would be

observed, who could be missionaries or misióneros,

how many misióneros could be

assigned to each misión, and

how many soldados or if any

would be stationed at a misión.

In turn, the state paid for the misióneros'

overseas travel, the founding costs of a misión,

and the misióneros' annual

salary. In addition, España intended to introduce the Natives of Nueva España’s Nuevo Méjico to certain aspects of Hispano

culture. In the case of northern Nuevo Méjico, the home of my progenitors, the misión efforts found river valleys surrounded by snow-covered

mountains. But it was also

harsh and unforgiving; one early settler called it a “glorious

hell.” The Españoles,

who came to this area in the late-16th-Century C.E., had brought their

century's old agricultural and irrigation system traditions with them to

the Nuevo Mundo.

They found that the valleys near the Río

Grande could be farmed when streams were channeled into irrigation

systems. More than two

centuries later, they would move east across the Sangre

de Cristo Mountains into new, greener valleys.

Later, the Españoles

would encounter new influences from a rapidly expanding United States of

America. It should be stated here that the misiónes

were not intended to be permanent. Most

anti-Spanish, anti-Catholic writers would have us believe that the

Catholic Church in concert España

planned to have these used indefinitely as reservations.

The truth is the Spanish government thought that within a

generation or two, the Natives would become loyal Spanish citizens or Ciudádanos,

reclaim their land, and contribute to the Spanish economy.

It was also believed that skilled immigrants would follow the

Franciscans to these areas and become pobladores there. The

best laid plans of men and all of that. As dictated by a larger plan, the

misiónes would be followed by presidios, next Spanish villas,

ranchos, and estancias,

and mines. Later, the misióneros supported by Real

Cédula or Royal Decree would establish autonomous Native-Christian villas. After the founding of a misión,

the Corona Española would usually provide military protection and

enforcement from a nearby presidio.

The Corona Española

would provide protection and order through its presidios.

The term presidio is

taken from the Spanish word “presidir”

meaning "to preside" or "to oversee."

These were fortified bases for military operations which were

established by España in

those areas it wanted to maintain control and/or influence over. At its inception, the royal

government would organize groups of Spanish pobladores

to populate the sparsely settled frontier areas in Spanish villas. The government

would also build military guarniciónes

or garrisons along the border. This

it did with the intent that the soldados

stationed in the presidios

would establish families and remain in the area once they retired, as

was the case with my progenitors, the de

Ribera. By the 18th-Century C.E., the

next two pronged phase would begin in Nuevo

Méjico. That initial

plan had begun with exploration of suitable sites for habitation, the

establishment of a misión,

followed by the building of a protected presidio

for keeping Spanish villas,

mines, ranchos, and estancias secure. These

were followed by a Catholic religious Native villa.

It would then progress to a secularized Native villa. Introduction of the Natives of Nueva

España’s Nuevo Méjico to certain aspects of Hispano

culture would be attempted later via a formally established recognition

of Native pueblos.

A joint institution of Native communities, the Church, and Corona

Española was be instituted later in response to difficulties

arising from having left control of relations between Natives on the far

flung northern frontier to pobladores and soldados.

At times, the early governance model of these regions led to

antagonized and abused Natives. Therefore,

it was believed that the Españoles

goals of military, political, economic, and religious expansion in North

America would succeed only to the degree the misión effort succeeded. Each Native villa would have communal property, labor, worship, political life,

and social relations all influenced by the misióneros

and insulated from the possible negative influences of other

non-Christianized Native groups and the Españoles

themselves. To achieve these

ends, the Christian villas

would have to be highly organized and disciplined. Daily life would follow a

well-structured routine. First

and foremost was prayer. It

was followed by the work necessary to ensure self-sufficiency.

Without work there could be no crops and meat from the cattle and

sheep. Churches, buildings,

homes, and agricultural structures would need to be constructed.

Training of the villa’s inhabitants was critical to its success.

Meals for a large workforce had to be properly planned and

prepared on time. There was

also some time for relaxation. All

of this was followed by frequent religious holidays and celebrations. It was hoped that the Natives of

the villa would mature in

their Christianity. It was

expected that this would be closely intermeshed with the Natives

learning Spanish political and economic practices until they would no

longer need a special misión

status. In this closely

supervised setting their communities could finally be incorporated into

normal secularized Spanish society.

This not to say that the policy would immediately overcome the Nuevo Mundo’s highly-regimented racial

and class distinctions. The

transition from official misión

status to ordinary Spanish society was to be no easy matter.

Additionally, Spanish laws for Nueva

España had no specified time for this transition to take effect. However, increasing pressure for

the secularization of most misiónes

would develop during the last decades of the 18th-Century C.E. forcing

these changes. In the end,

there would then be an official transaction for such a transition.

The misión's communal

properties were to be privatized. Direction

of civil life was to become a secular governance model.

The direction of church life would be transferred from the misiónero

religious orders to a Catholic diocesan church. The Spanish government also hoped that

intermarriage between Españoles

and the Natives would increase. They

planned for villas to grow up

around the misiónes, which

would then become parish churches. As

a result of this policy, the land on which the misiónes

were established was not given to the Catholic Church and remained the

property of the Spanish government.

It was intended to be held in trust for the Natives. As the Españoles explored the vast areas of the most northern part of Nueva

España, they named the Natives of the north "ranchería

people." Their fixed

points of settlements or rancherías

were usually scattered over an area of several miles and one dwelling

may be separated from the next by up to a half-mile.

Most of these ranchería

people were agriculturalists and farming was their primary activity.

In Nuevo Méjico

proper, they found the Pueblo,

Navajo, Apache, and other Native tribal groups.

However, early on they did not find the Comanche. Given the circumstances of Spanish governance in

the Nuevo Mundo, exploration

led to control of large expanses of water and land which were very

difficult to manage. Exploration

of new territories had remained an important part of España’s

efforts in Nueva España

and Nuevo Méjico.

Her policy for gradual settlement continued to be based upon the

process of misión

founding and placement, presidio

establishment, Villa building

and populating (Both for Españoles

and Christianized Natives), and finally the granting of ranchos and estancias.

In this way there was an orderly way to settle each forward area.

But, how was an area to be effectively and efficiently maintained

after initial settlement? The aforementioned Spanish

policies and strategies speak to a higher level of purpose.

The reality on the ground was quite different.

Therefore, before proceeding with this chapter we must first look back to how

Spanish settlements in Nueva España

and Nuevo Méjico were

established, supplied, survived, and then developed from 1598 C.E

through the resettlement period led by de

Vargas in the 18th-Century C.E. Spanish authorities had accepted

the reality that no wealthy Native empires like that of the Aztecas

conquered in 1521 C.E. would be found north of Nueva

España’s Méjico City.

Thus, España’s misión

policy and resulting history in the Southwestern part of the North

American Continent would be different from that of Azteca

Méjico. It reveals much

about España’s strategy for expanding in the region.

Misiónes were to

become the basis for future explorations, settlement, and the overall

maintenance of the vast areas of the region. What are today’s Américano

states of Florida, Nuevo Méjico, Tejas,

Arizona, and Las Californias

were systematically explored for the establishment of Roman Catholic misiónes

to be founded for the propagation of its doctrines.

The Franciscan order and its frayles

would found a series of misiónes

in Florida after 1573 C.E.

These would be established along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

The first misiónes in Nuevo Méjico were later to be established by frayles accompanying de Oñate's

expedition of 1598 C.E. The period of 1600 C.E.-1610 C.E. brought with it

further Spanish exploration of the region.

It had been the Late-16th-Century C.E. policy of the Españoles

to assign Catholic misióneros

as the principal agents for opening up new lands and the pacification of

the Natives. These were at

the vanguard of the exploration of Nueva

España and Nuevo Méjico.

In addition, the Corona Española also sent out military explorers.

This continued to be the rule.

The Spanish expeditions of Francisco

Vázquez de Coronado (1540 C.E.-1542 C.E.) and Don

Juan de Oñate (1598 C.E.) convinced those in power that the only

gold to be found in the northern parts of Nueva

España was that of the Native soul.

Thus, the conversion of the Natives of the region became España’s

major goal. By 1598 C.E., Capitán

and legal officer, Gaspar Pérez

de Villagrá (1555 C.E.-1620 C.E.)

was placed at the head of an expedition which went forward under the

broader Juan de Oñate

Expedition. Between 1601 C.E.-1603

C.E., de Villagrá served as

the alcalde mayor of the Guanacevi

mines in what is now the Méjicano

state of Durango. He is better

known for his authorship of Historia

de la Nueva Méjico, published in 1610 C.E.

His work tells a great deal about España’s

earliest presence in Nuevo Méjico. De Oñate was born in the Nueva España’s

city of Zacatecas to

Spanish-Basque colonists and Silver mine owners.

His father was Cristóbal

de Oñate, a descendant of the noble house of Haro,

and his mother Doña Catalina

Salazar y de la Cadena who was a descendant by her maternal line of

a famous Jewish Converso

family the Ha-Levi's. His ancestor Cadena,

in the year 1212 C.E., fought in the Battle of Las

Navas de Tolosa. The

family was granted a coat of arms and thereafter known as Cadenas.

Juan de Oñate married Isabel

de Tolosa Cortés de Moctezuma, granddaughter of Hernán

Cortés, the conqueror of the Triple Alliance, and great

granddaughter of the Azteca

Emperor Moctezuma II Xocoyotzin.

He was hardly a Spaniard of “Clean Blood” that most

Anglo-American writers would suggest.

He was in fact a man that exemplified the multi-cultural

(Jewish/Christian) reality of el

Imperio Español and married a part-Azteca

wife. This should have made

the Old Christians envious and critical of his efforts. From this point on, I will now present the Spanish

settlement of Nuevo Méjico in

a timeline fashion, as it is easier to convey the information to the

reader. The initial

settlement period we will view as beginning in 1599 C.E with de

Oñate Expedition and ending in 1680 C.E. with the Pueblo

Insurrection or Revolt. The

second settlement or resettlement period began in 1692 C.E. with the de Vargas re-entry and ends with his death in 1704 C.E.

The third settlement period begins after de

Vargas’ death in 1704 C.E., continues through the consolidation of

the governance of Nuevo Méjico and expansion throughout northern Nueva España until 1800 C.E. The first Spanish group was to the settle Santa

Fé de Nuevo Méjico area in 1598 C.E.

At this juncture, it is necessary to clarify a critical

historical reality of the conditions into which the Españoles

entered when they migrated northward to Nueva

España’s Nuevo Méjico

and beyond. It has occurred

to me that few non-Spanish commentators and historians view this

complexity in its entirety. By

this, I mean to say that the study and understanding by non-Spanish

historians of Spanish Nueva España

sets the historical stage with misunderstandings of the Españoles

and their Native (Indian) relations. Many

non-Spanish writers see this period of history through a perspective

which presents Natives as one large homogeneous group.

This is done rather than presenting the Natives as what they

were, a series of heterogeneous warring tribes which were constantly

vying for power and control over the lands and resources of their

enemies, of which the Españoles

were only one. The warring

Native tribes didn’t care who their enemy was at any given point in

time. An enemy was simply an

enemy. The ignorant would

also tend to see the Spanish Period as having Españoles

only originating from Iberian Peninsula stock, rather than from many

European nations both under the Imperio

Español and from without it. In

addition, many would not include those of mixed races (Mestízos,

Mulatos, etc.) who willingly became Españoles

in the sense of becoming an active, engaged, participant of that Empire

serving her alongside other members of that Imperio

Español. It should be said that presenting Natives as one

large group serves the Anglo-American, Northern European, non-Spanish,

anti-Spanish historical narrative where all Spaniards (as one large

group of Iberians) are bad and all Natives (as one large group of

Natives) are good. These

misguided commentators cannot for the life of them, leave-off using the

terms conquistador, colony, colonists, colonizing.

Interestingly, all others making it into the region can be

considered natives after some period of settlement.

The Apache and Comanche

were not always native to Nuevo Méjico,

and yet they are constantly referred to as migrants and then Natives.

Even the Américanos

are considered pioneers and later settlers, their colonies are never

mentioned. Where is the

fairness? In addition, the relationships between the Natives

were ever changing and dependent upon many factors and conditions that

existed on the ground at any given time.

In short, relationships were fluid.

The context of the Spanish and Native relationship in the region

must be viewed in this light. The

enemy of my enemy is my friend, and all of that. By the early-17th-Century C.E., the Spanish Misión

System was already a guiding institution in northern Nueva

España and Nuevo Méjico.

It sought to incorporate Natives into the Imperio

Español, with its Catholic religion and Hispano

culture. The system

accomplished this through formal establishment and recognition of Native

communities under the tutelage of misióneros

and the protection and control of the Corona

Española. The Españoles had already established presidios or fortified guarniciónes

of troops incrementally to protect its misiónes,

mines, ranchos or ranches, and

estancias or farms of the

heartland of Nueva España. These

were fortified bases for military operations which were established by España

in those areas it wanted to maintain control over and/or influence.

These presidios or

fortresses were built to protect against pirates, hostile Natives, and

invaders from enemy nations. In

western North America, a rancho

del rey or king's ranch would be established a short distance

outside a presidio.

This was a tract of land given to the presidio

as pasturage for horses and other beasts of burden of the guarnición.

These presidios

protected them from attacks by hostile forces from the remote northern

areas. The first Gobernador

of Nuevo Méjico, Juan de Oñate (1598 C.E.-1610 C.E.), was under the Virreinato

of Nueva España. As such,

he was watched carefully and dealt with harshly when he failed to meet

its expectations. He was a

strict, demanding Gobernador

who overstepped his bounds of authority which would lead to his removal.

During his tenure the Españoles

granted Estancias to pobladores.

Estancia is used here

for landed estates of significant size and smaller for Nuevo Méjico. To use

the term hacienda would be

imprecise, as it also refers to landed estates of significant size.

In this decade, smaller holdings were termed estancias

or ranchos. These were

owned almost exclusively by the Españoles

who were either Peninsulares

(Born in España.) or Criollos (Born in the Nuevo

Mundo) and in rare cases by Mestízos

or individuals of mixed-race. In

Méjico landed estates of

significant size would be termed haciendas. In addition, “Land Grants” were made both to

individuals and communities during the Spanish Period (1598 C.E.-1821

C.E.) of Nuevo Méjico.

Unfortunately, nearly all of the Spanish records of land grants

that were made in what is now Nuevo Méjico prior to the Pueblo

Insurrection (Revolt) of 1680 C.E. were destroyed in that insurrection.

Thus, historians can often only be certain of land grants that

were made after the Spanish Resettlement of Nuevo

Méjico in 1693 C.E., or termed the “Reconquest” by many

writers. When discussing the

period, the preferred term is “Resettlement.”

As a point of reference there were two major types of land

grants, private grants made to individuals and communal grants made to

groups of individuals for the purpose of establishing settlements.

Communal land grants were also made to Native Pueblos

for the lands they inhabited. Given the fact that some of my progenitors entered

Nuevo Méjico, by 1598 C.E.,

it is necessary to present certain facts regarding the various Natives

tribes in the region. However,

first I will introduce some of my progenitors.

To clarify, I haven’t

offered much information on family lines other than the de

Ribera as it would be almost impossible to do them all justice in

such a limited family history. However,

here I will attempt to offer some insights into some of those other

three family lines. Notes: Firstly,

I am a direct descendant of Pedro

Lucero de Godoi (Godoy). His

was one of the “First Families” of Nuevo

Méjico who were members of the original de

Oñate settlement Expedition by the Corona

Española to Nuevo Méjico

(1598 C.E.). They remained

until 1680 C.E., and retuned during the Reconquest of 1692 C.E.

Juan

Lucero de Godoi (1625 C.E.-1693

C.E.) was Pedro's

eldest son. He served as

Secretary of Government and War in 1663 C.E.

Until 1693 C.E., he claimed

to have served the King for fifty-two years, from the time that he was

seventeen until his then present age of sixty-nine.

He had resided in Santa Fé

for forty years; his property there was at the "Pueblo

Quemado." Juan

was a Sargento Mayor and the Alcalde

Mayor of Santa Fé when he escaped the Indian siege of 1680 C.E.

with his wife, four grown sons bearing arms, and four grown daughters.

The next year, he was described as having a good stature with a

large, pock-marked aquiline face, crooked nose, and fifty-nine years

old. (Origins, p.60) Nicolás

Lucero de Godoi, a grandson,

was born in Nuevo Méjico, on

1635 C.E. to Juan Lucero de Godoy

and Juana De Carvajal.

Nicolás Lucero married

María Montoya and had 3

children. He passed away on

1727 C.E. in Albuquerque. Miguel

Lucero [(de

Godoi or Godoy) (Great Grandson of) was born in 1668 C.E. to Nicolás

Lucero de Godoi and María

Montoya. He died on June

15, 1709 C.E. and was buried at Zuñi

Pueblo, Nuevo Méjico. Miguel

Lucero (de Godoy) was born at Zuñi

Pueblo, Nuevo Méjico. He was

married María Ángela Teresa

Vallejos at Bernalillo, Nuevo Méjico in 1700 C.E. She

was the daughter of Manuel

Vallejos González and María

Nicolása López Solis. Miguel Lucero was found to be living in the Río Abajo at the start of the century. María

Ángela Teresa Vallejos was

born before October 16, 1685 C.E. in Ciudád

de Méjico, Nueva España,

baptized on October 16, 1685 C.E. in Ciudád

de Méjico, Nueva España

and died after 1750 C.E. in Nuevo

Méjico, Nueva España. Diligencia

Matrimonial: In 1700 C.E., at Bernalillo

Miguel Lucero (de Godoy), Santa

Fé Presidio soldier, son of Nicolás

Lucero and María Montoya,

natives of Nuevo Méjico

living here, married María Ángela

Teresa Vallejo, daughter of Manuel

Vallejo and María López

Solis, both deceased. Witnesses:

José Mascareñas (age 32) native of Méjico City, notary; Joaquín

Sedillo (age 35), native of Nuevo

Méjico, Cristóba; Jaramillo

(age 36). The

children of Miguel Lucero de Godoy

and María Ángela Teresa Vallejos

were: Manuel, María, born December 1, 1708 C.E., and Manuel Miguel II born on January 6, 1710 C.E. He

was born after the untimely death of his father who was wounded at El

Morro. Manuel

Miguel died shortly after at Zuñi

on June 15, 1709 C.E., where he was buried in the Misión's sanctuary on the Lectern Side

also called the Epistle Side of the church.

On December 8, 1710 C.E., his widow acted as sponsor with one Pedro

Lucero, who could well have been her brother-in-law, and one of the

sons of old Nicolás Lucero de

Godoy. Manual

Miguel Lucero

(de Godoy) II (G-G

Grandson of) was born on January 6, 1710 C.E. at Alburquerque,

Provincia de Nuevo Méjico in

the Virreinato de Nueva España.

He died January 25, 1766 C.E. in Tomé,

Provincia de Nuevo Méjico part of the Virreinato de Nueva España. He

was the son of Miguel Lucero de

Godoy and María Ángela

Teresa Vallejos. Manual

Miguel married: (1)

María

Rosa Baca in 1740 C.E.

She died on June 6, 1755 C.E. (2)

Antónia

Durán y Cháves He

was father of Joséfa Lucero; Diego

António Lucero; Miguel António

Lucero; Manuel Lucero; María de Loreto Lucero, and 12 others. Manuel

Miguel was the bother of María

de la Luz Lucero, half-brother of

Rosalía Romero; Capitán

Pedro Romero; Tadeo Romero;

Rosa Margarita Romero; Quiteria

Romero and, 2 others. His

occupation was that of a farmer. Loreto Lucero [Daughter of Miguel

Lucero (de Godoy) II] married Eusebio

Varela Eusebio

Varela is descended from Pedro

Varela. Juan

António (c.1742 C.E.-d.?) was

his son. Eusebio

Varela descended from the Varelas

as follows. In 1598 C.E., Juan de Onate conquered Nuevo

Méjico and established a Spanish colony there.

Among the soldados

serving under him were the Varela

brothers. Alonso Varela was of a native of Santiago, Galicia, España.

He was of good stature, chestnut colored beard, 30 years of age,

son of Pedro Varela.

He supplied a complete armor for himself and his horse.

Alonso had a brown beard and was of a good stature.

Most of de Oñate’s

soldados were not described as having “a good stature.”

Alonso was a brother to

the Pedro Varela. Pedro

Varela was also a native of Santiago, Galicia, España. He

was of good stature, red-bearded, 24 years of age, son of Pedro

Varela, and supplied the complete armor for himself and his horse.

He was “of a good stature” and “red-bearded.”

He was a brother to Alonso

Varela. From

Don Juan de Oñate, Colonizer

of New Mexico 1595-1628, Vols. I & II:

Statement of what I, Pedro Varela, am taking to serve his majesty in the Indies in Nuevo

Méjico: ·

One set of armor consisting

of a coat of mail, cuisse, and beaver of mail ·

One strong buckskin jacket ·

One harquebus with its

equipment ·

One hooked blade ·

One sword ·

One pound of powder ·

One set of horse armor ·

One leather shield ·

Ten horses and one donkey ·

Half a dozen pairs of

horseshoes with nails ·

Two jineta

saddles with all their trappings and bridles “I

am taking all of this to serve his majesty, and I swear by God and this

cross that everything contained herein is mine.

Done on this day, December 7, 1597 C.E., Pedro

Varela.” There was a

list for his brother Alonso,

though Alonso brought 12 horses and 2 mules.

Alonso was sworn in on

the same day as Pedro. It

is from this family line that the Varelas

descend. Juan

Lucero de Godoy (Antónia Varela de Losada,

Juan, Pedro, Pedro, Pedro)

was born 1684 C.E. at Santa Fé, Nuevo Méjico.

He died on November 23, 1741

C.E. at Santa Fé, Nuevo Méjico.

On May 7, 1713 C.E., he married Ysabel

López Lujan at Santa Fé,

Nuevo Méjico.

She was born 1692 C.E. at Santa Fé, Nuevo

Méjico and died August 9, 1771 C.E. at Santa Fé, Nuevo

Méjico. She was the daughter

of Pedro Lujan and Francisca

Martín Salazar.

Children of Juan Lucero de Godoy and Ysabel

López Lujan were as follows: ·

María

Antónia Lucero

de Godoy was born in 1714 C.E. at Santa

Fé, Nuevo Méjico. She

married Luís Varela Jaramillo who

was born in 1710 C.E. at Santa

Fé, Nuevo

Méjico. He was the son of Cristóbal

Varela Jaramillo and Leonor

Lujan Dominguez. They

were married on November 23, 1729 C.E. at Santa

Fé, Nuevo

Méjico. ·

Juan

Lucero de Godoy was born in

1716 C.E. at Santa Fé, Nuevo Méjico. ·

Francisca

Alfansa Lucero de Godoy was born in 1718 C.E. at Santa Fé, Nuevo Méjico. She

died January 1786 C.E. at Albuquerque,

Bernalillo Nuevo Méjico. She

married Salvadór Manuel Secundo Armijo. ·

María

Ygnacia Lucero de Godoy was

born in 1721 C.E. at Santa Fé,

Nuevo Méjico. She

married Manuel Sáenz Garvisu. ·

Ysabel

Lucero de Godoy was born 1722

C.E. at Santa Fé, Nuevo Méjico.

She died in 1758 C.E. at Santa

Fé, Nuevo Méjico.

She married Alonzo García

de Noriega. ·

Pedro

António Lucero

de Godoy was born in 1724 C.E. at Santa

Fé, Nuevo Méjico.

He married Margarita Lobato. José

Varela (Son of Eusebio)

married Rita Otero Bernardo

Varela (Son of José) married Altagracia López Marcelina

Varela (Daughter of José)

married Cruz Cebelles (Ceballos) Amalia

Ceballes (Daughter of Cruz)

married Isidro Ribera (Rivera) With all of that said, we will now get on with our

story.

Ten years after the Españoles settled Nuevo Méjico

in 1598 C.E. the Navajos had

obtained sheep, cattle and horses from Pueblo

Natives and were tending them. After

1700 C.E., the Españoles

would find the Navajo to be a

scourge because of their constant raids and alliances with other

Natives. The tribe managed

intermittent peace with one tribe or another, while it raided and fought

the Españoles and others. The

Navajo feared only the Utes,

who learned Plains warfare and used it effectively.

It is clear that once the Plains tribes acquired the horse, they

developed Native warfare into an art.

These Pueblo

Natives were groups of natives in central Nuevo

Méjico and northeast Arizona

that resided in permanent stone or adobe

dwellings. The term “Pueblo”

refers to a cultural classification, which disregards language and

tribal lines that separate the various Pueblo

groups. The Pueblo

were mainly agricultural, growing principally beans and maíz along with pumpkins, and sometimes cotton.

Despite the arid weather, the Pueblos

were excellent farmers. The

Natives did some limited hunting, mostly for jackrabbits.

Crafts such as weaving, pottery, and basket making were fashioned

with great skill and artistry. Women

crafted pots, made bread, and were the owners of the homes and gardens.

The men and women shared in activities such as basket and cloth

weaving, basket, building houses, and farming.

Individual “pueblos”

were independent identities that had connections to other pueblos

through related customs and languages. Converting the Pueblo Natives through misión

efforts became an integral goal of Spanish governance.

It should be noted that many Pueblos

converted for the protection against their traditional enemies the Apache

and the Navajo which the

Spanish presence afforded them. Later,

with religious conversion not complete among the Pueblos,

there emerged forms of resistance which would lead to war.

It must be said that they occasionally raided

nearby tribes. Later, when

the Españoles first began

settling in what is now the American Southwest they changed the dynamics

of the region by introducing horses.

The Apache quickly

adopt horses into their culture. Unfortunately,

as they did, they used them to dominate their neighbors through mobile

warfare. A report on the Apache would be compiled and printed for the King of España

later at Madrid in 1630 C.E. It

was written by a Nuevo Méjico

misiónero Franciscan fray.

Called “The Memorial

of Fray Alonso Benavides,” it was a comprehensive account of the Apaches

as they existed in that period. Wherein,

Benavides refers to all the outlying native tribes in Nuevo

Méjico as Apaches. He classifies

them as Gila Apaches, Navajo Apaches, and Apaches

Vaqueros. It must be

stated here that even then the Apaches

were a terror to the other native tribes of the region.

However, at that point in time they did not present a difficulty

for the Españoles. What is also of importance is the fact that the

Native Pueblo villages on the Río

Grande were surrounded by the Apache

nation. It was written that

as a people, the Apache

“were very fiery and bellicose, and very crafty in war.

Even in the method of speaking, they show a difference from the

rest of the nations.” Here

one must accept that before the arrival of the Españoles

Native vs. Native warfare was already a harsh reality.

The Españoles would

only be one more tribe to contend with.

There were many other Native tribes in the various

regions of Nueva España.

Many of these were warlike and would challenge the Españoles

for supremacy.

With Spanish expansion, Natives of the region

would begin to have concerns about encroachment upon their traditional

territories. These included,

the Navajo, Pueblo, and to some degree, the Apache.

The Comanche, however,

had not yet arrived on the scene in full force and were not impacted. The decade of 1620 C.E.-1630 C.E., saw continued

exploration and the planting of misiónes.

During the next 100 years the Franciscans would found more than

40 additional misiónes, most

of these along the Río Grande.

Fray Alonso de Benavides

was especially influential in directing the founding of 10 misiónes

between 1625 C.E.-1629 C.E. Thereafter,

he promoted them ably in España. The misiónes

of San Buenaventura and San

Isidro were established at the Pueblo

de Las Humanas at the Gran

Quivira which is located at the top of the windy Chupadero

Mesa on the south rim of the Estancia

Basin of central Nuevo Méjico.

During the early period of Spanish settlement of Nuevo

Méjico, Franciscan misióneros

undertook the conversion of the Salinas

Pueblos. Four of the misiónes established at that time are now included La

Purisma Concepcion at Quarai,

San Gregorio at Abó, and San

Buenaventura and San Isidro at

Gran quivira, or Pubelo de Las Humanas, as it was called in the 17th-Century C.E.

The other Salinas misiónes

were at Cililí, Taxique, and Tabirá.

The church of Misión San

Isidro was constructed between 1629 C.E.-1631 C.E.

The convento of this

original misión was situated

in a remodeled and extended portion of the house block north of the

church. Misión

San Buenaventura de las Humanas (Gran

Quivira) was established in 1629 C.E. Expansion of Spanish control over the area of Nueva

España outside of Nuevo Méjico

was also a feature of España’s

policy. To ensure that a

continuing string of presidio

protection was developed and employed for Nueva

España’s northern most areas, protective presidios

continued to be established and manned during this decade such as the Presidio

de Santa Catalina de Tepehuanes (1620 C.E.-1690's C.E.?) in Santa

Catarina de Tepehuanes, Durango.

There was also the placement of the Presidio

San Gregorio de Cerralvo, founded in 1626 C.E. in Nuevo

León, Méjico. Other Misiónes

and villas were also being built at a steady pace during the period. Overseeing all of this for Nuevo Méjico under the Virreinato

of Nueva España was

Juan Álvarez de Eulate y Ladrón de

Cegama (1618 C.E.-1625 C.E.).

He was born in Améscoa Baja, a town in Navarra,

northern España.

As a Spanish soldado who served with distinction in the Netherlands.

In 1602 C.E., de Eulate travelled to Flanders at his own expense and enlisted in

the army of Albert VII, Archduke of Austria.

Juan

Álvarez fought with valor in the brutal and protracted Siege

of Ostend, and was twice wounded. He

served under Don

Ambrogio Spinola Doria, 1st Marqués

of the Balbases Grandee of España in two

expeditions into Friesland, again distinguishing himself for his

bravery. In 1608 C.E., he

was given a certificate testifying to his excellent character and

service, and was allowed to return to España.

De Eulate was also a Capitán

in the Spanish fleet from 1608 C.E. to 1617 C.E.

Juan

Álvarez would be followed by Gobernador

Felipe de Sotelo Osorio (1625 C.E.-1630 C.E.)

who had joined the Spanish Navy in his youth, eventually becoming an

Admiral. Both of these Gobernadores

provided land grants for ranchos

and estancias in the Provincia. Those living

in the region would experience Navajo

unrest as a continued problem, while the Pueblo

and Apache contributed few

difficulties. The Comanche

as of yet had not come on the scene. The decade of

1630 C.E.-1640 C.E. brought

with it continued Spanish exploration in the region along with the

establishments of misiónes.

San Isidro Misión

in San Isidro, Doña Ana

County in Nuevo Méjico was

built between 1630 C.E. and 1635 C.E. of limestone quarried on site.

The church measured 109 feet long by 29 feet wide.

Inglesia de

San Isidro was very similar in design to the church at Abó.

A campo santo, or

walled cemetery, is attached to the structure just east of the church.

From 1631 C.E., Misión San

Isidro was administered as a Visita

of Abó, until 1659 C.E., when the new church and convento of San Buenaventura

were begun. A Visita was a visiting station or encampment of friendly Natives

close to a misión.

The Inglesia de San Isidro

was a focus of treasure hunters following the abandonment of Gran

Quivira. The Santa Fé

Presidio continued providing

protection for the region. The

Villa of Santa Fé was the capital and economic hub of the region and

administered by four Gobernadores

of Nuevo Méjico under the Virreinato

of Nueva España during the decade.

The first was Gobernador

Francisco Manuel de Silva Nieto (1630 C.E.-1632 C.E.).

He was followed by Gobernador Francisco de la

Mora Ceballos (1632 C.E.-1635 C.E.), Gobernador

Francisco Martínez de Baeza

(1635 C.E.-1637 C.E.), and Gobernador

Luís de Rosas (1637 C.E.-assassinated

1641 C.E.). These continued

land grants for both estancias

and ranchos. Natives in the region, the Navajo, Pueblo, and Apache

were relatively calm. The Comanche

were not yet a pronounced problem. The decade of

1640 C.E.-1650 C.E. had continued Spanish exploration and misión

building. In seeking to

introduce both Catholicism and European methods of agriculture, the misiónes

encouraged the Natives to establish their settlements close by, where

the frayles could give them

religious instruction and supervise their labor.

Unfortunately this arrangement exposed the natives to European

diseases, against which they had little immunity.

An epidemic in Nuevo Méjico

killed 3,000 Natives (Natives) in 1640 C.E.

This did not stop the establishment of Misión San Gregorio de Abó in 1640 C.E. by Fray Francisco Acevedo. Spanish presidio

placement continued in northern Nueva

España for the protection of the Españoles.

The Presidio de San Miguel

de Cerrogordo (1648 C.E.-1767 C.E.) in Villa Hidalgo Durango was

one such addition. The decade brought a new Gobernador of Nuevo Méjico,

Juan Flores de Sierra y Valdés (Died

1641 C.E.) a Spanish soldier who

joined the Spanish Army in his youth and later became a General of the Army. He was soon followed by Gobernador

Francisco Gómes (acting, 1641 C.E.-1642 C.E.), Francisco Gómes was

born in 1576 C.E. in Villa de Coima, Portugal.

He was the son of Manuel Gómes and

Ana Vicente and became an

orphan at an early age. Francisco was then raised in Lisbon

by his only brother, Alvaro

(or Alonso) Gómes,

a Franciscan who worked as a high sheriff of the Holy Office of the

Inquisition. His family was

probably of noble origin. Gómez resided for a time in Madrid

at the house of Alonso de Oñate,

the brother of Juan de Oñate.

This placed him in the court of King Felipe

II during the king's illness. Gómes probably

lived there until the death of king in 1598 C.E.

The next Gobernador was Alonso de

Pachéco de Herédia (1643 C.E.). He

was followed by Gobernador Fernando

de Argüello (1644 C.E.-1647

C.E.), and Gobernador Luís

de Guzmán y Figueroa (1647 C.E.-1649 C.E.).

Each would provide for new land grants for estancias

and ranchos and provide for

governance of the mostly peaceful Natives of the region. In the years of 1650 C.E. to 1660 C.E., there

would be continued activity in the areas of exploration.

Misión planning and

administration would be ongoing in the mid-1600s C.E., as Spanish

officials created the Jurisdicción

de las Salinas near the area of Misión

Nuestra Señora de Purísima

Concepción de Quarai which included Las

Humanas, Abó and Quarai, as well as Cililí,

Tajique, and Tabirá. Presidio protection remained an important aspect of Spanish control

during the period. The Villas

of the region continued to grow and prosper.

Four Gobernadores would administer Nuevo

Méjico under the Virreinato

of Nueva España, Gobernador Hernándo de Ugarte

y la Concha (1649 C.E.-1652 C.E.), Gobernador

Juan de Samaniego y Xaca (1652

C.E.-1656 C.E.). Gobernador Juan Manso de Contreras

(1656 C.E.-1659 C.E.) followed de

Samaniego y Xaca. De

Contreras was born in la

Villa de Loarca, Consejo de Valdes, in Oviedo

(Asturias, España). He

lived in Sevilla (Andalucía, España).

Juan Manso was the

younger half-brother of Fray Tomás

Manso who later became the bishop of Nicaragua. This

appointment led to good relations with the Franciscans.

Juan and Tomás Manso traveled to Nueva

España around 1652 C.E., on a mission to supply caravans from Méjico City

to Santa Fé, Nuevo Méjico.

By 1656 C.E., he was involved with mission supply wagons. Juan

Manso was appointment Gobernador

of Santa Fé de Nuevo Méjico in 1656 C.E.

He soon issued legislation against the Pueblo

Natives, over religious issues. Contreras

would create many enemies among the pobladores

in Nuevo Méjico.

One of these enemies was a soldier, Francisco

de Anaya Almazán. Almazán occupied several important positions in both military and

administrative areas of government.

Manso had him jailed,

although he was able to escape with the assistance of Pedro

Lucero de Godoy and Francisco

Gómez de Robledo. The

reasons of imprisonment of Anaya

are unknown. Manso

was replaced in the Nuevo Méjico government

in 1656 C.E. by Bernardo López de Mendizábal.

Gobernador Bernardo López

de Mendizábal (1659 C.E.-1660 C.E.). De

Mendizábal (1620 C.E.-September

16, 1664 C.E.) was a Spanish politician, soldier, religious, and native

of what is today Méjico.

He served as Gobernador of

Nuevo Méjico between 1659 C.E.-1660 C.E. and as alcalde

mayor, or royal administrator in Guayacocotla

on the Sierra Madre Oriental,

northeast of Méjico

City. De

Mendizábal was born about

1620 C.E. in the town of Chietla,

in Puebla (present-day Méjico) at the family’s hacienda.

His father, Cristóbal López de Mendizábal, was a Basque Capitán and legal representative.

His mother, Leónor

Pastrana, was the granddaughter of Jew, Juan

Núñez de León.

De León

had been prosecuted by the Inquisition for having been accused of

secretly practicing the Jewish religion.

López also had a

brother, Gregorio López de Mendizábal.

López studied arts and canon law at a Jesuit college located at Puebla

and finished his studies at the university in Méjico City.

Mendizábal would later

join the Spanish Army, where he served in the "Galleon

de la Armada" and was stationed for a time at the Presidio

of Cartagena de Indias in

modern-day Colombia.

López occupied

government positions in Nueva

Granada, Cuba, and Nueva España. Among other of Lopez's directives as gobernador

of Nuevo Méjico,

he prohibited the Franciscan priests from forcing the Natives to work

without being paid. He was

one who recognized the rights of the Natives to practice their religion.

Lopez also permitted

the Pueblos to perform their

religious dances and religious practices which had been prohibited for

over 30 years. These

decisions caused disagreements with the Franciscan misióneros

of Nuevo Méjico

in their relations with the Natives.

A man named Contreras

moved to Méjico City,

where he remained until 1661 C.E. In

that same year, he was appointed Alguacil

mayor, or chief constable, to Nuevo Méjico. His responsibility was to

arrest Bernardo López de Mendizábal

following a commission from the Inquisition.

Mendizábal was

arrested in the spring of 1663 C.E. before completing his

administration. He was

condemned to prison by the Inquisition on thirty-three counts of

malfeasance and the practice of Judaism in 1660 C.E., leading to his

being replaced in 1663 C.E. De

Mendizábal died in prison before the final verdict was reached.

His arrest may have been due to his mother, Leonor

Pastrana, a granddaughter of a Jew, Juan

Núñez de León. Juan

was prosecuted by the Inquisition for having been accused of being a

secretly practicing Jew. Contreras

later moved to Parral, in Nueva Vizcaya where he became

administrator of the Nuevo Méjico Misión wagons.

He supplied wagons while working in Parral

until his death in 1671 C.E. Each of the gobernadores

had guided the provisioning of land grants for new estancias and ranchos and

had also continued Spanish efforts to Hispanicize the region’s Native

populations. By the decade of 1660 C.E.-1670 C.E., exploration

and misiónes were permanent

ways of life for the region’s pobladores.

With continued protection from the Presidio

of Santa Fé and the Villa

prospering, its Spanish population thought all was well.

Unfortunately, the Spanish Provincia

de Nuevo Méjico was to become the victim of a looming catastrophe in

the decades of the 1660s C.E. and 1670s C.E.

With repeated disputes between Franciscan frayles and royal gobernadores

over the use of Native labor and differing attitudes toward Native

religious practices, the Pueblos

were conflicted. Additionally,

the Españoles were prone to

rancorous disputes and occasional violence, as each partisan faction

vied for preeminence. Under these political conditions the Pueblo

Natives of the Provincia

became the objects of attack for their beliefs.

They were alternately persecuted for practicing them and later

having them tolerated. However,

the Church could not and would not condone them.

As for Native labor, it was at times abused and its resulting

products were appropriated by greedy government officials and

over-zealous misióneros.

The resulting widespread discomfort and anger in Nuevo

Méjico was exacerbated by unending droughts, contagious diseases

and their ravages, and Apache

raids against all quarters of the Provincia.

This combination of circumstances and their negative impacts

would later reach their severest levels during the 1670s C.E. Yet, even with these problems the Españoles

flourished.

The Villa of Alburquerque

(present-day Albuquerque, Nuevo Méjico) was founded in 1660 C.E. to meet the needs for

expansion. To administer the

Villa and the rest of Nuevo

Méjico four new Gobernadores

for Nuevo Méjico would be appointed.

The Virreinato of Nueva

España appointed Diego Dionisio de Peñalosa

Briceño y Berdugo (1661 C.E.-1664 C.E.).

He was a Lima-born soldado.

Peñalosa's

administration was notable for its positive treatment of the Pueblo

Natives and their religious practices.

This earned him the hostility of the Roman Catholic frayles,

who were determined to Christianize Native populations.

He later was declared a blasphemer and heretic by a Catholic

tribunal. Forced into exile,

he would become an active opponent of España’s interests and offered his services to England and

France, España’s rivals in

the colonization of the Nuevo

Mundo. On March 6, 1662

C.E., he led the Quivira

Expedition. This expedition

was later turned into a legend with a variety of fantastic objects. Juan

Durán de Miranda (First time as governor 1664 C.E.-1665 C.E.) was

a soldier who served as Gobernador of

Nuevo Méjico in the 1600s

C.E. He occupied the

position of Gobernador of

Nuevo Méjico twice (1664 C.E.-1665

C.E. and 1671 C.E.-1675 C.E.). He

was arrested in 1665 C.E. Despite

this, he was eventually appointed for a second term in Nuevo Méjico

in 1671 C.E. During this period, the Nuevo Méjico

government, the state, and the Church clashed.

Power over civil and ecclesiastical jurisdictions was at issue as

one of the authorities abandoned its responsibility thus undermining the

provincial government. This

caused the Natives to increasingly reject the power and authority of el

Imperio Español. In

addition, the Misión Supply Service of the

Mansso Administration became ineffective which damaged Nuevo Méjico's stability. Since the misiónes

supplied food for the territory's population, this failure negatively

impacted the region. In July 1671 C.E., Miranda elevated Juan Domínguez

de Mendoza to the rank of Mariscal

del Campo or Field Marshal and led a military campaign against the Gila

Apache and the "Siete Ríos

Apaches," in the south of Nuevo Méjico. During de Miranda’s first administration, a faction led by Tomé

Domínguez de Mendoza accused and filed charges against Juan.

These charges caused Miranda to be imprisoned for a brief period in the Casa

de Cabildo or Council Jail at Santa

Fé.

In addition, he was subjected to "an iniquitous

residencia." This

was a judicial review of an official’s acts conducted at the

conclusion of his term of office. In

this case for it was for wickedness.

All of his goods were confiscated.

However, later he was released when he argued successfully at Méjico City against the

accusations for which he was charged. Also,

he was able to recover his property and position. In 1675 C.E., Miranda was replaced by Juan

Francisco Treviño as Gobernador. Next, came Gobernador

Tomé Domínguez de Mendoza

(acting, 1664 C.E.). De

Mendoza (1626 C.E.-After

1692 C.E.) was a

Spanish soldier (native of modern Méjico) who served as acting

Gobernador of Nuevo Méjico in 1664 C.E.

De Mendoza was born in

1626 C.E., in Méjico

City. His father was a

Spanish officer with the same name who arrived in Nuevo Méjico with the Juan

de Oñate expedition of 1598 C.E.

He had at least two siblings including the soldier Juan

Domínguez de Mendoza. De

Mendoza joined the Spanish

Army in his youth. Before

1662 C.E., he lived below Isleta

Pueblo, Nuevo Méjico.

When Mendoza arrived in

Nuevo Méjico,

a faction led by him accused and "filed grave charges" against

the Gobernador of

the provincia of Nuevo Méjico

Juan Durán de Miranda, which

caused imprisonment and the seizure of his goods.

In 1664 C.E., Tomé

was appointed Acting Gobernardor of Santa Fé de

Nuevo Méjico. However, his government

would only last a short time. Juan Durán de Miranda (1664 C.E.-1665

C.E.) was released from prison

when he defended his actions while in office about the charges issued

against him in Méjico City, recovering his government position in the provincia a year later. In August 1680 C.E., Tomé, his family, and other residents of Río Abajo, Nuevo Méjico would escape to

El Paso del Norte, Ciudád

Juarez in what is today modern Méjico.

The present-day Méjicano

villa of Paso del Norte at

Ciudád Juárez was founded in

1667 C.E. There,

he held several positions. One

of the positions he occupied was Maeses

de Campo "with full complement of arms."

In 1681 C.E.,

Mendoza, at sixty-one years

old, died from gout and a stomach disease. Gobernador Juan Durán de Miranda (1664 C.E.-1665 C.E.) was then followed by Gobernador

Fernando de Villanueva y

Armendáris (1665 C.E.-1668

C.E.). Fernando (died

May 17, 1679 C.E.) was a Spanish soldier, judge, and politician who

served as Gobernador of Nuevo Méjico. Fernando

was born in the early

17th-Century C.E. in San Sebastián,

in Quetzaltenango.

He was the son of Fernando de Villanueva y Armendáris and Clara de Irigoyen. In

1630 C.E., as a teenager, he was enlisted in the Marina

de guerra real Español of España

or Spanish Royal Navy. By

1634 C.E., he was promoted to the rank of second alférez

in the army of Cataluña.

There, he fought against the French, which attempted to invade Leocata

(a place in Cataluña), and he

successfully drove out the besieging army.

In April 1637 C.E., he joined the Royal Indian Navy, where he

fought in Algarve (in southern

Portugal).

Also, he received the promotion to soldier in the presidio,

on the Caribbean island of St. Martin, while in the army. He became a Teniente and sargento mayor

or sergeant major of the presidio

on the island. On four

occasions, Villanueva traveled

to Puerto Rico to get supplies

that were needed on the island. In

three of these trips, he had to fight against hostile forces.