|

Chapter Four The Old World Iberia, Pre-Spain

The search for one's family history is a labor of love. With enough research a family picture begins to emerge, almost bringing some ancestors back to life. One begins to see them as real people rather than ancestors whose lives are spoken of in print or just a face found in a faded photo. In time, I learned enough about some to feel as though I know them. The experience has changed my life and perceptions of family. They are now my family, thus my love for my ancestors, the de Riberas of New Mexico. My family's story begins in the fiercely fought over Iberian Peninsula, which was later to become known as Spain. It was forces beyond the control of any of the Iberian inhabitants that impressed a deep love of God, country, and honor upon their Spanish souls. Thus my mother, Angela Rivera (de Ribera), sprang from a long line of warring peoples that melded together into what are known today as the Spaniards. My mothers people were of ancient Iberians, Roman, Jewish (Sephardic), and the succession of other tribes that found their way to that beautiful peninsula. There they fought one another for possession of the land and its promise. Each tribe rose to power and gradually lost it to another. Hungry and determined to make the place their own in time they mingled their bloodlines until they became one common stock, todays Spanish. Mother's pride in her Spanish heritage, family, and its history was always a topic of discussion at the evening dinner table. That pride and love of family never left me. My genealogical search began with my maternal grandfather, Isidro Rivera (de Ribera) y Quintana. He was born in Pecos, New Mexico in 1870. Soon, the search included my maternal grandmother, María Anna Amalia Ceballes, originally Ceballos. She was also born in Pecos, on August 5, 1878. They were married in Pecos, New Mexico on January 25, 1898. As Mimi Lozano-Holtzman of Somos Primos fame has taught me, a genealogical project involves a passion for research, data collection, analysis, and documentation. The aforementioned are necessary and, at times, difficult. The result of the research process is a mountain of documents and notes. These records necessitate a filing system. Accessing a poorly developed system can overwhelm the researcher. As a result, an easily retrievable electronic database is suggested. This should be supported by well thought out file folder system or tabbed binders. The research process requires the development of a unique skill-set. These include the ability to review personal and legal documents with an eye toward linking them to one's family lines. It requires patience and sound judgment. Data collection is one of the building blocks of any research project. The documents often have misspelled and/or differently spelled names. The researcher will also find conflicting and incorrect dates for births, deaths, marriages, etc. He/she must integrate into family lines. Another very important skill is that of, "People Interfacing". Important leads are often found through others. In my case, it was the kindness of Michael Gallegos and Marcus Flores that often removed roadblocks and provided directions around the always-present blind alley. An added bonus is that these two men are newly found, long lost family. These wonderful people saved me countless hours of needless research through their kindness and efforts. Months into the project, I found a new group of friends. They are "The History Hunters", my fellow researchers, dedicated men and women with a love of family. This is a gift that I can never be too thankful for. They remind me of the tough minded Spanish, New Mexico settlers that are my family lines. Like the Spanish men and women who came to the Southwest and built lives and fortunes in a very unforgiving environment these history hunters never give up. The name Ribera is Spanish in Origin. It is first found in Castile, where it originally meant "riverbank". In time, it was used as a surname. In earlier times, it was often seen with the prefix "de", to indicate the place of origin of a family. Spelling variations of the name include Rivera, Ribera, Ribeira, Rivero, Ribero, Ribeiro, and others. Don Fernando Rivera of Santa Fe provided a Ribera Coat of Arms. It's depicted by a green shield with three horizontal red stripes. This chapter will introduce the reader to these hardy peoples, Iberians who melded into what would become the Spanish. These would later settle the Spanish New World. To know who they were and what they were about is important. It provides the reader with an understanding of what motivated them, what drove them to leave the comfort of Europe and its traditions, and to venture outside to the world of the unknown.

What is a Spaniard?

I provided a primer in "Chapter One" in an attempt to ease the reader into some understanding of this complex subject, Spain and its people. Most of us are limited in our knowledge and understanding of the human race, racial groups and types, and geographic migration patterns. We know only what we are taught and what we see with our own eyes. Thus labels are easy to apply while research and study of the area takes time and trouble. Spain is an excellent study in ethnic, tribal, and racial mixing. Modern European states are a result of this mixing. Population migration patterns, conquest, and wars make Spain an excellent case study in this regard. To complicate matters further, Spain became a world-wide empire comprised of regionalized viceroyalties. Politically, it became a geographically extensive group of state-like districts or provinces governed by a viceroy. These territories and different peoples (ethnic groups) were united and ruled by a central authority, a Spanish monarch.Many people of different European countries intermarried with Spaniards and these too became Spaniards. Later indigenous Americans, Asians, and Africans were introduced into the mix. In this chapter I will attempt to expand upon how Spain was formed and by whom. I will also provide a historic look at the intentions behind the Empire and how this unfolding changed its own ethnic, racial, and cultural composition. Thus the question, what is a modern day Spaniard? The history of Spain is really a history of a geographic area, a peninsula. Before the Roman Empire, the Iberian Peninsula was never politically unified. It had indigenous groups and colonies established by Eastern Mediterranean civilizations. It is traditional (Only since 19th Century) to start the history of modern Spain with the Visigoth kingdom. To be sure, a discussion of modern Spain would be incomplete without a mention of the Visigoth Kingdom. However, it is debatable whether there is continuity between it and the Kingdom of Castilla and Aragón after the 15th Century. Continuity can however, be established via the tread of Roman Catholic Christianity. Both the Visigoth Kingdom (German Tribes) and Al-Andalus (African Moors) have their own historical significance and must be treated as such.

The Iberians 2000 B.C. The first people to appear in the Iberian Peninsula were called Iberians. These are accepted by historians as the native people (at a given point in time) of what is now called Spain. Originally they came from the south of Africa (Libya). They had a tribal organizational structure and were therefore split up into various tribal groups. Early on, the Iberians established a pattern of transhumance according to season. Taking their sheep up into the mountains in summer, they spent the time tending to small plots. In the province of València, which is inland from a town called Saguntum, there was excavated a city at La Bastida. In ancient times it was a farming village and many tools were found in the burned ruins. From the tools it is inferred that the farming was done with a light plow, using draught animals, such as oxen. Also, the soil would have been slightly moist, implying the now dry soil must have been irrigated. This in turn implies a cooperative effort, as irrigation requires a community united to a common goal. All this predates Greece, Carthage, and Rome. Therefore, the primitive Iberians accomplished this form of irrigation.In winter, they brought their flocks down to the Mediterranean where they were sheared and stabled. Then the people wove textiles during the cold months. This life in constant motion gave the Iberians a hearty lifestyle and a love of freedom. They would learn the city life with its gains and losses later with the Romans. The general conclusion is that the Iberians were probably happy with their lot. They had enough to eat and remained tightly knit communities. However, the coming of the metal age was not necessarily to their benefit. The Iberians had strong contact with the classical world. Both the Greeks and Phoenicians traded with them and eventually established settlements on the peninsula. In addition to trading with the classical world, the Iberians provided mercenaries to various countries around the Mediterranean by the 5th Century B.C. 1100 B.C.: Cadiz was founded in 1100 B.C. and is the capital of the province of the same name in the Spanish region of Andalucía. The city is sited on a long narrow peninsula in the southwest corner of Spain, surrounded on three sides by the Atlantic Ocean.

The Jews: 970 - 928 B.C.

Later, the Celts arrived in Spain. They were a typically Aryan people. These moved into Spain during the 8th to 6th centuries B.C. Before the expansions of Ancient Rome and the Germanic tribes, a significant part of Europe was dominated by Celtic culture. The seven territories recognised as Celtic nations are Brittany (Breizh), on the European continent; Cornwall (Kernow), Wales (Cymru), Scotland (Alba), Ireland (Éire), and the Isle of Man (Mannin). Each of these regions has a Celtic language that is either still spoken or was spoken into modern times. Territories in north-western Iberia (Spain) particularly Galicia, Northern Portugal and Asturias; sometimes referred to as Gallaecia, which includes North-Central Portugal are sometimes included due to their culture and history. Unlike the others, however, no Celtic language has been spoken there in modern times.The Celts blended in with the native Iberians to produce the Celtiberians. With the merging of two groups there arose a new people. These then, divided into several tribes Cantabrians, Asturians, and Lusitanians giving their names to their respective homelands. These were Celtic and Proto-Celtic tribes living in the remote northern mountain areas of Spain. Today, the word Celtic usually denotes people who are descended from one of seven Celtic "fringe" provinces in Western Europe. Only now, is the public at large aware of the Celts of Galicia, Spain. The Celtic peoples oldest cultural remnants can be found close to eastern France, Southern Germany and Belgium, and northern Switzerland and Austria. These spread from Galatia, Turkey to Celtiberia, Spain and Ireland in the 1st Century B.C. Today, many descendants of immigrants to North America, South America, Australia, and New Zealand can trace their ancestry from the Celts. Fortunately, the Celtic culture was situated on the borders of western civilization instead of in the center, where major changes took place. As a result, Celtic civilization offers a window into a world that existed before many of the conventions were brought about in Western society. It has been compared in this respect to the Hindu culture of India, the other "fringe" culture of the Arian expansion in Europe. There are many similarities in their culture and their beliefs, which span back to the formative years of Western civilization. Celt, also spelled KELT, Latin CELTA, plural Celtae, is a member of an early Indo-European people. These peoples spread over much of Europe from the 2nd millennium B.C. to the 1st Century B.C. Their tribes and groups eventually ranged from the British Isles and northern Spain to as far east as Transylvania, the Black Sea coasts, and Galatia in Anatolia (Turkey). In part, they were absorbed into the Roman Empire as Britons, Gauls, Boii, Galatians, and Celtiberians. Linguistically they survive in the modern Celtic speakers of Ireland, Highland Scotland, the Isle of Man, Wales, and Brittany. Phoenicians

They extended their influence across North Africa and settled Carthage in the modern nation of Tunisia. A trading post, the word Carthage means "New City." They selected it because of its location in the center of North Africa. It was a short distance from Sicily and the Italian Peninsula. Then the Assyrians and the Persians conquered the original homeland of the Phoenicians, Carthage became an independent state. Early on, they were attracted by mining wealth of the Iberian Peninsula. They founded a number of trading posts along the Spanish coast, the most important being that of Cádiz.

The Greeks: 350 B.C.

We marvel at the words and thoughts of those great Greeks Plato, Socrates, Pythagoras, and Aristotle that are still taught in universities to this day.

The ancient Greeks were very loyal to their city-states (polis). Each had its own personality, goals, laws and customs. But what did it mean to be a citizen of a Greek city-state? Greek citizens took great pride in their individual states, defining themselves as citizens of that city-state, rather than citizens of Greece. This was a great civilization far ahead of its time, whose beauty and knowledge will live on for many generations to come. This is what these Greek explorers and traders brought to the Iberian Peninsula. Until about 350 B.C., Iberia had few Greek traders. Soon they discovered Saguntum. Saguntum is the Roman name, while Sagunto is the modern Spanish translation. València is the city, which replaced Sagunto, is one of the largest in Spain. The name Murbiter was used during the Arab occupation, then quickly dropped when the Arabs were expelled.

The mountains behind Saguntum are steep, but not high. The Iberians used the higher plateaus for pasturing sheep in the summer and growing wheat and barley where water was plentiful. The winters behind Saguntum were severely cold and summers dry. At the city itself, the climate was a little more temperate, but still hot and dry in the summer. Historically Saguntum is seen as having been situated in a location that would cause great controversy. The city strived to maintain neutrality and did so for hundreds of years. During these times, the kings of the Iberian tribes looked for ways to create competition. With more traders, their bargaining power rose accordingly. Until about 350 B.C., Saguntum was an Iberian village with a few Greek traders. Soon, Greeks arrived from their homeland Phocaea, and later, Greece proper. They settled, setting up industries in the "frontier land", plying their trades. To the north, the villages or colonies were also Greek. These settlements extended northward along the coast as far as the Spanish and French border. Nice was the last Greek settlement, where the Alps plunge into the Mediterranean. Its central location made the city a great prize. Later, along the Roman road Via Augusta, it was two hundred miles south to Cartagena and one hundred miles north to Tortosa on the Ebro River. Two hundred miles further and one arrives at the French border, the edge of the Alps at the Mediterranean. To go inland to Madrid, the center of Spain, it is another 220 miles. As the Greeks became successful they ran afoul of the Etruscans. Through their main colony, Marseilles, the Greeks traded goods brought overland and down the Rhone River. The main item of trade was tin. Their Etruscan competitors were bringing tin to Italy by crossing the Alps and dealing directly with the Celts. The Greeks began competing heavily with the Etruscans and prospered greatly, angering the Carthaginians and Etruscans. The Carthaginians had colonies to the south, along the coast all the way to Cádiz. From there, they controlled trade goods coming around the Atlantic coast, especially tin. The tin trade provided the flame that would ignite hostilities. The Greeks saw themselves as under attack from all sides. Pressed, they appealed to the Romans, setting up an alliance. This allowed the Greek colonies to carry on trade without problem from 350 B.C. to 219 B.C. Their workshops manufactured finished products and they traded them to the east. The Jews: 587 B.C. Tradition suggests that this second wave arrived as refugees after the destruction of Jerusalem by the king of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar, in 587 B.C., joining their compatriots who had come earlier during the Phoenician trading era. Though all this is possible, there is no documentation to prove it.The Carthaginians: Before 238 B.C. Carthage would eventually fight and lose three brutal wars against its rival, the city of Rome, Italy. These wars were known as the Punic Wars because Puncia was the Roman name for Carthage. Once entering Spania, as they called Spain, the Phoenicians struggling against the Greeks. As a result, they called upon their Carthaginian brothers. Earlier these had lost the First Punic War against Rome when the Roman navy surprised that sea trading people in 238B.C. Stripped of its land and rights in Sicily, Carthage sought a place to expand, Iberia was that place. Under the orders from Carthage, Hamilcar Barca

of took possession of most of Spain. It was this act that caused Rome to

raise a border dispute to defend the areas of Greek influence. This

began the Second Punic War on the Peninsula which was to decide the fate

of the world of that time. Earlier, Rome had absorbed the Etruscans and

extended their empire along the northerner coast of the Mediterranean to

the Greek-held colonies of Gaul and Iberia. In the treaty signed by

Hasdrubal in 241 B.C., the Carthaginian general ceded all the lands

north and east of the "River" to Rome and its allies. Celt, also spelled KELT, Latin CELTA, plural Celtae, is a member of an early Indo-European people. These peoples spread over much of Europe from the 2nd millennium B.C. The Rome Period: 218 B.C.-19 B.C. The Roman presence in Hispania would last for seven centuries during which the basic frontiers of the Peninsula in relation to other European countries would be shaped. However the Romans did not only bequeath a territorial administration, but also left a legacy of social and cultural characters such as the family, language, religion, law and municipal government, and the assimilation of which definitively placed the Peninsula within the Greco-Latin and later the Judeo-Christian worlds. The Roman presence in the Peninsula followed the route of the Greek commercial bases; however, it commenced with a struggle between itself and Carthage for the control of the western Mediterranean during the 2nd Century B.C. In any case, it was at that time that the Peninsula would enter as an entity in the international political circuit then in existence, and from then on became a coveted strategic objective due to its singular geographic position between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, and to the agricultural and mineral wealth of its southern part.

When Hamilcar Barca of Carthages died from accidental drowning in the year 228 B.C., the mantle of authority was passed to his son, Hannibal. 219 B.C.: Hannibal attacked the Greek City, Saguntum in 219 B.C. causing the Second Punic War. The inhabitants of Saguntum greatly feared Hannibal and his men. The city fathers sent regular delegates to the Roman Senate pleading their concern and warning of the preparation for war. The Romans took a position that Saguntum was part of their territory in Spain and sent a delegation to talk with Hannibal. Getting no satisfaction over the claims for Saguntum, the delegation went to Carthage to have Hannibal removed or at least stopped. After much posturing, claiming the Greeks were harassing the native Iberians near Saguntum, and counter-claims that the Iberians were harassing the Greeks colonists, Hannibal attacked Saguntum. Hannibal arrived at the gates of a city beginning its rapid decline into oblivion.

Hannibal was wounded in the leg and the remainder of the assault was left to his brothers. Hannibal later left his brother, Hasdrubal II, in charge of Iberia and supplies to be sent forward later. Unfortunately, his brother was unable to save Saguntum or the supplies.

Suguntum and other newly acquired Carthaginian bases in Spain provided the great military leader Hannibal with excellent position to attack his enemies. He soon led a team of elephants across southern France and into Italy; his great march over the Alps. While Hannibal was crossing the Alps, Scipio, the great Roman general, arrived in Massillia to stop the Carthaginians. But he had arrived too late. Scipio then immediately began to undo all that Hannibal had achieved in Iberia. Apparently the poor treatment of the citys inhabitants had soured the native Iberians and caused many to go over to the Roman cause. Where before, Hannibal had recruited soldiers from the Iberian population, Hasdrubal drove the Iberians into the enemy camp. Interestingly, the Romans and Carthage fought each other with the aid of Iberians troops. Hannibal had many of their best troops aiding him in his many early victories. The Roman General with the aid of angry citizens finally recaptured the city. After the Roman victory, Publius Cornelius Scipio, Africanus began his final conquest of Spain. The Romans then took over the Carthaginian territories in Hispania. Over the next couple of centuries they expanded to conquer the rest of the Iberian Peninsula.

209 B.C.: Decline of Hannibal's army in Italy and beginning of the great Roman conquest of Spain. Rome annexes the country and divides it into two provinces:

206 B.C.: For the most part, Iberia was conquered by 206 B.C. After that time, only a few northern Iberian tribes remained free. She would defeat the remaining warrior tribes by the time most of Spain was conquered. The peoples of note left to be defeated were the Proto-Celts and Galicians. History tells us that the Romans had particular difficulty conquering one of these tribes, the Galicians. 153 B.C.: Numantia is famous for its role in the Celtiberian Wars. Numantia or Numancia in Spanish is the name of an ancient Celtiberian settlement, whose remains are located 7 km north of the city of Soria, on a hill known as Cerro de la Muela in the municipality of Garray. In the year 153 B.C., Numantia experienced its first serious conflict with Rome. 146 B.C.: After the siege of Carthage in 146 B.C., the Romans went from house-to-house slaughtering the Carthaginians. The few survivors were sold into slavery after the city and harbor was destroyed. In an act of vengeance the Romans poured salt over the land to ensure its barrenness. 143 B.C. to 139 B.C.: Viriatus and the Lusitanians fought the Roman legions. 138 B.C: By 138 B.C., the Romans moved in and occupied the area of València. Unfortunately, the city of Saguntum had been mostly destroyed. The city center was moved twenty miles south to València. Both cities, the old and the new, lie in the province of València, a land of native Iberians, mixed with the occasional Roman, Punic Arab, or Greek. 133 B.C.: The inhabitants of Numantia prefer to die in the flames of their city rather than surrender to Scipio Aemilianus. After 20 years of hostilities, in the year 133 B.C. the Roman Senate gave Scipio Aemilianus Africanus the task of destroying Numantia. He laid siege to the city, erecting a nine kilometre fence supported by towers, moats, impaling rods and so on. After 13 months of siege, the Numantians decided to burn the city and die free rather than live and be slaves.The Romans would pacify the Peninsula once and for all and divide it into three provinces:

By 75 B.C.: Pompey the Great destroyed a large part of València during the campaign against Quintus Sertorius. (Livy).

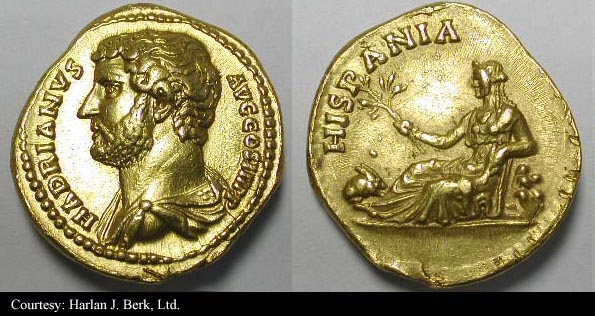

Roman conquest of Hispania, North West corner of Iberia: 19 B.C. The last part of Iberia to be absorbed was the North West corner in 19 B.C. Hispania or Spain remained under Roman rule for six centuries. During this time the Peninsula was completely subdued and romanized. As the Romans settled Iberia, they expanded the existing irrigation systems and changed the crops to their liking. The Romans often took a great idea and expanded it to its logical greatness. When the Romans occupied a city they didnt consider it a proper place to live without a theater, and Saguntum was no exception. The amphitheater was built in the 1st Century A.D., in a natural hillside depression. Even today, it offers exceptional acoustics. It has recently been rehabilitated and events are now held as in ancient times. The Roman circus was built in the 2nd to 3rd centuries, as the lust for amusement swept the Roman Empire. Several of the present-day universities are built on these Roman foundations in València, today a thriving Spanish tourist Mecca. Roman Circus Gate, one of the gates to the Roman Circus, is located in the Calle de los Huertos (Street of Gardens). It is composed of enormous smooth-cut masonry and has been dated to the 2nd and 3rd Century B.C. Monuments include the Temple of Diana, built of gigantic limestone blocks in the 5th and 4th Century B.C. The Temple of Diana, or a wall fifty feet long, still remains. The wall is now part of the Church of Santa María and survives because Hannibal would not touch the sacred temple. Later the Christian church rebuilt the temple, but now dedicated to the Virgin Mary instead of the goddess Diana. The Castle on the Sierra Calderona ridge, above Saguntum, is the remains of the hilltop fortress of the type so common in the ancient world. Greek forums, later paved by the Romans, and now called Plazas can be seen along with columns and capitals carved from the local limestone. Several cisterns carved by the Romans into the native rock and sealed with waterproof cement can be found. One of the famous cisterns, now Plaza de la Conejera, was covered over by a small fortress. The cistern and its many columns formed the "basement". There used to be a tower called the Tower of Hercules it is now the Plaza de la Ciudadela (City Plaza) the tower was destroyed by French troops in 1811 A.D. It was the highest part of the overall fortress complex. Most of what one sees now was built in medieval times but is impressive. From this natural height there is still a magnificent view of the gardens and orchards running down the hillside to the blue Mediterranean. Roman thought and culture dominated Hispania. So much so that it produced writers of the stature of Seneca and Lucan. Also the eminent emperors as Trajan and Hadrian came from Iberia. Rome magnificent Rome left Spain four powerful social elements the Latin language, Roman law, the municipality, and the Christian religion. The Jewish Quarter or section of Saguntum was sectioned off and marked by an arch, or portal. It is an interesting area of narrow winding streets, typical of an ancient past. Jewish traders occupied the quarter, always insisting on their own version of edible food, etc. Typical of the Romans, they tolerated other cultures and their ways, allowing the capable Jewish merchants to bring goods to market. History was later made there when the Christians massacred the Jews in 1492. The doorway is known today as the Portalet de la Sang or Portal of Blood. Later, the ancient Jewish synagogue was occupied by the "Brotherhood of the Immaculate Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ". Jews: 70 A.D.

At the invasion of the Huns some Visigoths fled with Athanaric into the mountains of Transylvania. The majority turned to the Roman Emperor Valens for help asking to be taken into the Roman Empire. In 376 A.D., a force of 200,000 Visigoths crossed the Danube. But oppression by the governors led them to revolt. Angry, they crossed the country plundering as they went. Finally, they defeated and killed Valens in 378 A.D., near Adrianople. His successor, Theodosius, made peace with the Visigoths in 382 A.D. Theodosius' policy was to unite the Visigoths with the empire by means of national commanders appointed by the emperor. Wanting to maintain peace, he endeavored to unite the Arians with those who held the Nicene faith. After the death of Theodosius in 395A.D. the Visigoths elected Alaric of the Baltha family as their king. Alaric then sought to establish a Germanic kingdom on Roman soil. It was Alaric who brought his people into connection with Roman civilization. In 396 A.D., he invaded the Balkan Peninsula as far as the Peloponnesus and was given the Province of Illyria. He then began his war against the Western Roman Empire. By 401 A.D., he entered Italy. Alaric was victorious at Aquileia. But after the battle of Pollentia in 403 A.D., Alaric was forced to retreat. In 408 A.D., he demanded the cession of Noricum, Illyria Pannonia, and Venetia. He plundered Rome in 410 A.D., and soon after died in southern Italy.

Jews Iberian Peninsula Roman times: 100 A.D. to 300 A.D.

98 A.D.: Beginning with the rule of Trajan, he was the first Roman emperor of Spanish origin. 264 A.D.: Franks and Suevi invade the country and temporarily occupy Tarragona.

The skyline of towers and battlements, ragged against the empty, glaring meseta sky, is as famous as it is dramatic; the powerful landscape, which charged the paintings of El Greco, is as thrilling today as it was when he painted it in the 16th Century. El Greco lived and worked in Toledo for 37 years, and some of his most celebrated works are kept within the churches and galleries of the city. Whether you want to immerse yourself in great medieval architecture, absorb the intensities of one of the most powerful artists of Spain's Golden Age, or simply stroll through ancient streets, a day at least in Toledo is an absolute must for anyone travelling through central Spain.

Religious tolerance remained a feature of the city even after the Christian takeover of Toledo in 1085 A.D., a key victory in the wars of the Reconquest. It was an atmosphere in marked contrast to the Moorish Christian campaigns bloodily raging further south. The peaceful coexistence of these cultures lasted for a remarkable length of time, and the city became a center of religious, intellectual and artistic excellence, greatly patronized by royalty. This tolerance was at its most liberal under Christian rule during the 13th Century, and the stability it engendered formed the bedrock of a cultural dynamism unsurpassed in Spain: the wealth of art and architectural treasures that remain today bear witness to the prosperity and creative output of the time. Only in the 14th Century, with increasingly zealous Christian powers determined to homogenize the culture throughout Spain, did this enriching cosmopolitanism come to an end. In 1355 A.D. there was a pogrom in the city, and in 1391 A.D. Jews worshipping at the synagogue of Santa María la Blanca were massacred. A determined Ferdinand and Isabella, the Catholic Kings, created the Inquisition in 1480 A.D., with specific orders brutally to root out all Jews, and in 1492 A.D., they ordered the mass expulsion of Jews from Spain. It was the end of a great era for Toledo.

Just about everything you will want to see in Toledo is inside the city walls. Its ancient narrow streets will take you up to Plaza Zocodover, a small square high on the east side of town, the best place from which to get your bearings.

The plaza is triangular: from one corner Cuesta del Alcazar; from another, Calle de la Cuesta de las Armas heads back down the hillside, eventually leading to the road north out of the city. The mosque of El Cristo de la Luz is the main monument of interest in this part of town, so it is a good idea to visit it as you leave. From Plaza de Zocodover's third comer, Calle del Comercio plunges between dusty, old buildings into the heart of the city, offering the best route for leisurely exploration of some of Toledo's great monuments. This Toledo decision had implications of great significance. The result was a north to south delineation from Cantabria to the Strait of Gibraltar, instead of an east-west delineation of the Peninsula, pivoting between Lisbon and Cartagena. Secondly, it was significant because it

constituted a first attempt at the Iberian peninsular unity independent

of the rest of the Roman Empire. Therefore, the Visigoths are considered

the creators of the first peninsular kingdom. This Visigothic kingdom

would serve, time and again, as an important source of legitimacy for

any power trying to unite Hispania. Thirdly, the Pyrenees and Gibraltar

were no longer considered mere places of passage or points within a

larger Roman Imperial circuit. They became the limits or frontiers of a

state to be defended.

410:

410: The former Roman provinces of Gallaecia and northern Lusitania were established by the Suebi as a defacto kingdom about 410. During the 6th Century it became a formally declared kingdom identifying with Gallaecia. It maintained its independence until 585 when it was annexed by the Visigoths, and was turned into the sixth province of the Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania. 411: The Barbarian tribes sign an alliance with Rome, which enables them to establish military colonies within the Empire. 411: In 411 the various barbarian groups decided on the establishment of a peace and divided the provinces of Hispania among themselves sorte, "by lot". Many scholars believe that the reference to "lot" may be to the sortes, "allotments," which barbarian federates received by the Roman government, which suggests that the Suevi and the other invaders were under a treaty with Maximuss government.

414: The Spanish Visigothic Kingdom Period 414

416: In 416, the Visigoths entered the Iberian Peninsula, sent by the emperor of the West to fight off the barbarians who arrived about 409. 418: By 418, the Visigoths, led by their king Wallia, had devastated both the Siling Vandals and Alans, leaving the Hasding Vandals and the Suevi, who had remained undisturbed by Wallias campaign, as the two remaining forces in the Iberian Peninsula. 419: In 419, after the departure of Wallia to their new lands in Aquitania, a conflict arose between the Vandals led by their king Gunderic, and the Suevi led by king Hermeric. Both armies met in the Battle of the Nerbasius Mountains, but the intervention of Roman forces commanded by the Comes Hispaniarum Asterius broke off the conflict, attacking the Vandals and forcing them to move to Baetica, modern Andalucía, leaving the Suevi as virtual possessors of the whole province. 420: 429: In 429, as the Vandals were preparing their departure to Africa, a Suevi warlord named Heremigarius moved to Lusitania to plunder it, but was confronted by the new Vandal king Gaiseric. Heremigarius drowned in the Guadiana River while retreating; this is the first instance of an armed Suebi action outside the provincial limits of Galicia. Then, after the Vandals left for Africa, the Sueves were the only barbarian entity left in Hispania. King Hermeric spent the remainder of his years solidifying Suevic rule over the entire province of Galicia. 430: 430: In 430 he broke the old peace maintained with the locals, sacking central Gallaecia, although the barely romanized Galicians, who were reoccupying old Iron Age hill forts, managed to force a new peace, which was sealed with the interchange of prisoners; yet new hostilities broke out in 431 and 433.433: In 433 King Hermeric sent a local bishop, Synphosius, as ambassador, this being the first evidence for collaboration between Sueves and locals. It was not until 438 that an enduring peace, which would last for twenty years, was reached in the province. 438: In 438 Hermeric King of the Sueves became ill, having annexed the entirety of the former Roman province of Gallaecia, he made peace with the local population. He then retired leaving his son Rechila as King of the Sueves. Rechila saw an opportunity for expansion and began pushing to other areas of the Iberian Peninsula. This same year he campaigned in Baetica, defeating in open battle the Romanae militiae dux Andevotus by the banks of the Genil River, capturing a large treasure. 439: A year later, in 439, the Sueves invaded Lusitania and entered into its capital, Mérida, which briefly became the new capital of their kingdom. Rechila King of the Sueves continued with the expansion of the kingdom.440: 440: By 440 Rechila King of the Sueves besieged and forced the surrender of a Roman official, Count Censorius, in the strategic city of Mértola.441: The next year, in 441, the armies of Rechila King of the Sueves conquered Seville, just months after the death of the old King Hermeric, who had ruled his people for more than thirty years. With the conquest of Seville, capital of Baetica, the Suevi managed to control Baetica and Carthaginensis. It has been said, however, that the Suevi conquest of Baetica and Carthaginensis was limited to raids, and Suevi presence, if any, was minute. 446: In 446, the Romans dispatched to the provinces of Baetica and Carthaginensis the magister utriusque militiae (Master of the Soldiers) Vitus, who assisted by a large number of Goths, attempted to subdue the Suevi and restore imperial administration in Hispania. Rechila King of the Sueves marched to meet the Romans, and after defeating the Goths, Vitus fled in disgrace. There were no more imperial attempts were made to retake Hispania. 448: In 448, Rechila King of the Sueves died as a pagan, leaving the crown to his son, Rechiar. 448: Rechiar King of the Sueves, a Catholic Christian, succeeded his father in 448, being one of the first Catholic Christian kings among the Germanic peoples, and the first one to mint coins in his own name. Some believe minting the coins was a sign of Suevi autonomy, due to the use of minting in the late empire as a declaration of independence. Pretending to follow the successful careers of his father and his grandfather, Rechiar made a series of bold political moves throughout his reign. 448: Rechiar King of the Sueves first bold move was his marriage to the daughter of the Gothic King Theodoric I in 448, so improving the relationship between the two peoples. He also led a number of successful plundering campaigns to Vasconia, Saragossa and Lleida, in the Hispania Tarraconensis (Then the northeastern quarter of the peninsula, stretching from the Mediterranean to the Gulf of Biscay, which was still under Roman rule) sometimes acting in coalition with local bagaudae (local Hispano-Roman insurgents). In Lleida he also captured prisoners, who were taken as serfs back to the Sueves' lands in Galicia and Lusitania. 450: 455: Rome then sent ambassador to the Sueves, obtaining some conditions, but in 455 the Sueves plundered lands in the Carthaginensis which had been previously returned to Rome. In response, the new emperor Avitus and the Visigoths sent a conjoint embassy, remembering that the peace established with Rome was also granted by the Goths. But Rechiar launched two new campaigns on the Tarraconensis, in 455 and 456, returning to Galicia with large numbers of prisoners. 456: Emperor Avitus finally responded to Rechiar King of the Sueves' defiance on 456 in autumn, sending the Visigoths king Theodoric II over the Pyrenees and into Galicia, at the head of a large army of foedrati which also included the Burgundians of kings Gundioc and Hilperic. The Suevi mobilized their people and both armies met on October 5, by the Órbigo River near Astorga. The Goths of Theoderic II, fighting from the right, defeated the Suevi. While many Sueves were killed in the battle, and many others were captured, most managed to flee. King Rechiar fled wounded in direction to the coast, prosecuted by the Gothic army, which entered and plundered Braga on October 28. King Rechiar was captured later, in Porto, while trying to embark, being executed in December.In 456, one Aioulf took over the leadership of the Sueves. The origins behind Aioulfs ascension are not clear: Hydatius wrote that Aioulf was a Goth deserter, while the historian Jordanes wrote that he was a Warni appointed by Theodoric to govern Galicia, and that he was persuaded by the Suevi into this adventure. Either way, he was killed in Porto in June 457, but his rebellion together with the armed actions of Majorian against the Visigoths eased the pressure on the Suevi. In 456, the same year as the execution of Rechiar, Hydatius stated that "the Sueves set up Maldras as their king." This statement suggests that the Suevi as a people may have had a voice in the selection of a new ruler. The election of Maldras would lead to a schism among the Suevi, as some followed another king, named Framta, who died just a year later. Both factions then sought peace with the local Galicians. 1458: In 1458 the Goths again sent an army into Hispania, which arrived in Betica in July, thereby depriving the Sueves of this province. This field army stayed in Iberia for several years. 459: After the execution of Rechiar, the Gothic King Theodoric continued his war on the Suevi for three months, but in April 459 he returned to Gaul alarmed by the political and military movements of the new emperor, Majorian, and of the magister militum Ricimer a half-Sueve, maybe a kinsman of Rechiar while his allies and the rest of the Goths sacked Astorga, Palencia and other places, in their way back to the Pyrenees. When the Visigoths disposed of Rechiar, the royal bloodline of Hermeric vanished and the conventional mechanism for Suevi leadership died with it. 460: 460: In 460 Maldras King of the Sueves was killed, after a reign of four years during which he plundered Sueves and Romans alike, in Lusitania and in the southern extreme of Gallaecia along de valley of the Douro River. Meanwhile, the Sueves in the north chose another leader. Rechimund became their leader and not King of the Sueves. He plundered Galicia in 459 and 460. This same year they captured the walled city of Lugo, which was still under the authority of a Roman official. As a response, the Goths sent their army to punish the Suevi who dwelt in the outskirts of the city and nearby regions, but their campaign was revealed by some locals, whom Hydatius considered traitors. From that very moment Lugo became an important center for the Sueves, and was used as capital by Rechimund. 464: In 464, Remismund was an ambassador and travelled between Galicia and Gaul on several occasions. He became King of the Suevi and was able to unite the various factions of Suevi under his rule and at the same time restore peace. He was also recognized and perhaps even approved of by Theodoric the Goth King, who sent him gifts and weapons along with a wife. Under the leadership of Remismund the Suevi again raided the nearby countries, plundering the lands of Lusitania and the Conventus Asturicense, while at the same time fighting Galician tribes like the Aunonenses, who refused to submit to Remismund. 464: In the south Frumar succeeded Maldras King of the Sueves and his faction. 464: 464 closed a period of internal dissent of the Sueves and the permanent conflict with the native population. 466: The Suevi probably remained mostly pagan until an Arian missionary named Ajax, sent by the Visigothic King Theodoric II at the request of the Suebic unifier Remismund, converted them in 466 and established a lasting Arian church which dominated the people until their conversion to Catholicism in the 560s. 466: During the reign of Euric in 466 the Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse, named after its capital Toulouse, included the southern part of Gaul and a large portion of Spain. 468: In 468 the Suevi managed to destroy part of the walls of Conimbriga, in Lusitania, which was sacked and then mostly abandoned after the inhabitants fled or were taken back to the north as slaves. Next year they even managed to capture Lisbon, which was surrendered by its leader, Lusidio. He later became ambassador of the Suevi to the Emperor. The end of the chronicle of Hydatius in 468 doesn't let us know the later fate of Remismund. 470: 470: Little is known of the Suevi period between 470 and 550, beyond the testimony of Isidore of Seville, who in the 7th Century wrote that many kings reign during this time, all of them Arians. A medieval document named Divisio Wambae mentions one king named Theodemund, otherwise unknown. Other less reliable and very posterior chronicles mentions the reign of several kings under the names of Hermeneric II, Rechila II and Rechiar II. 480:

Beginning of the 6th Century: Theodemar's son and successor, King Miro, called for the Second Council of Braga, which was attended by all the bishops of the Kingdom of Galicia, from the Briton bishopric of Britonia in the Bay of Biscay, to Astorga in the east, and Coimbra and Idanha in the south. Five of the attendant bishops used Germanic names, showing the integration of the different communities of the country. King Miro also promoted contention with the Arian Visigoths, who under the leadership of King Leovigild were rebuilding their fragmented kingdom which had been ruled mostly by Ostrogoths since the beginning of the 6th Century, following the defeat and expulsion of Aquitania by the Franks. After clashing in frontier lands, Miro and Leovigild agreed upon a temporary peace. 500:

510:

540: 540: Thanks to a letter sent by Pope Vigilius to the bishop Profuturus of Braga circa 540, it is known that a certain number of Suevi Catholics had converted into Arianism, and that some Catholic churches had been demolished in the past in unspecified circumstances. 550: Second half of 6th Century: After a period of obscurity there is very little remaining information on the history of this area or in fact Western Europe in general. The Suebi Kingdom does reappear in the politics and history of Europe during the second half of the 6th Century. This follows the arrival of Saint Martin of Braga, a Pannonian monk, dedicated to converting the Suebi to Nicene Christianity and consequently into allegiance with the other Nicene Christian regional powers, the Franks and the Eastern Roman Empire.Under King Ariamir, who called for the First Council of Braga, the conversion of the Suebi to Nicene Christianity was apparent; while this same council condemned Priscillianism, it made no similar statement on Arianism. Later, King Theodemar ordered an administrative and ecclesiastical division of his kingdom, with the creation of new bishoprics and the promotion of Lugo, which possessed a large Suebi community, to the level of Metropolitan Bishop along with Braga. 556: In 556 Saint Fructuosus of Braga was appointed bishop of Braga and metropolitan of Galicia, ostensibly against his own will. During his later years the Visigothic monarchy suffered a pronounced decline. This was due in large part to a decrease in trade and therefore a sharp reduction in monetary circulation. It would appear that this was largely a result of early 8th Century Muslim occupation in the in the south Mediterranean. Gallaecia was also affected and Fructuosus of Braga denounced the general cultural decline and loss of the momentum from previous periods, causing some discontent in the Galician high clergy. 556: At the Tenth Council of Toledo in 556, Saint Fructuosus of Braga was appointed to the Metropolitan seat of Potamio after the renunciation of its previous occupier. At the same time the Will of the Bishop of Dume Recimiro was declared void after he donated the wealth of the diocese convent to the poor. 560: 561: The conversion of the Suebi to Catholicism is presented very differently in the primary sources. Threr is a contemporary record, "the minutes of the First Council of Braga". It met on May 1, 561. These state explicitly that the synod was held at the orders of a king named Ariamir. The first Catholic Council held in the Kingdom was almost entirely devoted to the condemnation of Priscillianism, making no mention at all of Arianism, and only once reproving clerics for adorning his clothes and for wearing granos, a Germanic word implying either pigtails, long beard, moustache, or a Suebian knot, custom declared pagan. Of the eight assistant bishops, only one bore a Germanic name, bishop Ilderic. His Catholicism is not in doubt. That fact that he was the first Catholic monarch of the Suebes since Rechiar is however contested on the grounds that he was not explicitly stated to have been a Catholic. He was the first to hold a Catholic synod. On the other hand, the Historia Suevorum of Isidore of Seville states that it was Theodemar who brought about the conversion of his people from Arianism with the help of the missionary Martin of Braga. And finally, there is the Frankish historian Gregory of Tours. An otherwise unknown sovereign named Chararic, having heard of Martin of Tours, promised to accept the beliefs of the saint if only his son were cured of leprosy. Through the relics and intercession of Saint Martin the son was healed; Chararic and the entire royal household converted to the Nicene faith. As the coming of the relics of Saint Martin of Tours and the conversion of Chararic are made to coincide in the narration with the arrival of Martin of Braga, circa 550, this legend has been interpreted as an allegory of the pastoral work of Saint Martin of Braga, and of his devotion to Saint Martin of Tours. We find King Ariamir with the bishops Lucrecio, Andrew, and Martin, during the First Council of Braga. Codex Vigilanus or Albeldensis, Escurial library Dahn equated Chararic with Theodemar, even saying that the latter was the name he took upon baptism. It has also been suggested that Theodemar and Ariamir were the same person and the son of Chararic. In the opinion of some historians, Chararic is nothing more than an error on the part of Gregory of Tours and never existed. If, as Gregory relates, Martin of Braga died about the year 580 and had been bishop for about thirty years, then the conversion of Chararic must have occurred around 550 at the latest. Finally, Ferreiro believes the conversion of the Suevi was progressive and stepwise and that Chararic's public conversion was only followed by the lifting of a ban on Catholic synods in the reign of his successor, which would have been Ariamir; while Theodemar would have been responsible for beginning a persecution of the Arians in his kingdom, to root out their heresy. Finally, the Suebic conversion is ascribed not to a Suebe, but to a Visigoth, by the chronicler John of Biclarum. He put their conversion alongside that of the Goths, occurring under Reccared I in 587-589. However, as such, this corresponds to a later time, when the kingdom was undergoing its integration with the Visigoths' Kingdom. 569: Later in January 1 of 569 Ariamir's successor, Theodemar, held a council in Lugo, which dealt with the administrative and ecclesiastical organization of the Kingdom. At his request, the Kingdom of Galicia was divided in two provinces or synods, under the obedience of the metropolitans Braga and Lugo, and thirteen episcopal sees, some of them new, for which new bishops were ordered, others old: Iria Flavia, Britonia, Astorga, Ourense and Tui, in the north, under the obedience of Lugo; and Dume, Porto, Viseu, Lamengo, Coimbra and Idanha-a-Velha in the south, dependent of Braga. Each see was then further divided into smaller territories, named ecclesiae and pagi. The election of Lugo as metropolitan of the north was due to its central situation in relation to its dependant sees, as well as because of the large number of Sueves dwelling in and meeting at the city. 570: 570: According to John of Biclaro, in 570 Miro succeeded Theodemar as king of the Sueves. During his time, the Suevic kingdom was challenged again by the Visigoths who, under their King Leovigild, were reconstituting their kingdom, reduced and mostly ruled by foreigners since their defeat by the Franks in the Battle of Vouillé. 572: In 572 Miro King of the Sueves ordered the celebration of the Second Council of Braga, which was presided by the Pannonian Saint Martin of Braga, as archbishop of the capital, thought Nitigis, himself a Suevi and Catholic archbishop of Lugo, had also a voice in the acts as metropolitan of the north. Martin was a cultivated man, praised by Isidore of Seville, Venantius Fortunatus and Gregory of Tours, who led the Sueves to Catholicism and who promoted the cultural and political renaissance of the kingdom. In the acts of the Council, Martin declared the unity and purity of the Catholic faith in Galicia and, for the first time, Arius was discredited. Notably, of the twelve assistant bishops, five were Sueves (Nitigius of Lugo, Wittimer of Ourense, Anila of Tui, Remisol of Viseu, Adoric of Idanha-a-Velha), and one was a Briton, Mailoc. 572: This same year of 572 King Miro of the Sueves led an expedition against the Runcones. This movement took place at a moment when the Visigoth King Leovigild was maintaining a successful military activity in the south: he had recovered for the Visigoths the cities of Cordova and Medina-Sidonia, and had led a successful assault on the region around the city of Malaga. 572: Sometime, late in the 5th Century or early in the 6th Century, a group of Romano-Britons escaping the Anglo-Saxons settled in the north of the Suebic Kingdom of Gallaecia, in lands which subsequently acquired the name Britonia. Most of what is known about the settlement comes from ecclesiastical sources; records from the 572 Second Council of Braga refers to a diocese called the Britonensis ecclesia ("British church") and an episcopal see called the sedes Britonarum ("See of the Britons"), while the administrative and ecclesiastical document usually known as Divisio Theodemiri or Parochiale suevorum, attribute to them their own churches and the monastery Maximi, likely the monastery of Santa María de Bretoña. The bishop representing this diocese at the II Council of Braga bore the Brythonic name Mailoc. The see continued to be represented at several councils through the 7th Century. 573: From 573 on, King of the Sueves, Miros, campaigns moved closer to Suevic lands, first occupying Sabaria, later the Aregenses Mountains and Cantabria, where he expelled some invaders. 576: Finally, in 576, King Miro of the Sueves entered in Galicia itself disturbing the boundaries of the kingdom, but Miro sent ambassadors and obtained of Leovigild King of the Visigoths a temporal peace. It was probably during this period that the Suevi also sent some ambassadors to the Frankish King Gontram. As recorded by Gregory of Tours, these were intercepted by Chilperic I near Poitiers and later imprisoned for a year. 579: Later, in 579, Leovigild's son, Prince Hermenegild of the Visigoths, rebelled against his father, proclaiming himself king. While residing in Seville, he had converted to Catholicism in open opposition to the Arianism of his father. T is claimed that he did this under the influence of his wife, the Frankish Princess Ingundis, and of Leander of Seville. It was not until 582 that Leovigild King of the Visigoths gathered his armies to attack his son. First, he took Mérida; then, in 583, he marched to Seville. Under siege, Hermenegild's rebellion became dependent on the support offered by the Eastern Roman Empire. It controlled much of the southern coastal regions of Hispania since Justinian I, and by the Sueves. This same year Miro, King of the Gallicians (Sueves), marched south with his army, with the intention of breaking on through the blockade. While camped, he was besieged by Leovigild King of the Visigoths and forced to sign a treaty of fidelity with the Visigoth king. After exchanging presents, Miro King of the Sueves returned to Galicia. There he lay in bed for days, dying soon after. According to Gregory of Tours, his death was due to "the bad waters of Spain". Leovigild later bribed the Byzantines with 30,000 Solidi, depriving his son of their support and ending the rebellion in 584. 579: On the death of Miro, in 579, his son Eburic was made King of the Gallicians (Sueves), but not before sending tokens of appreciation and of friendship to Leovigild. Less than a year later, his brother-in-law, named Audeca, accompanied by the army seized power. He placed Eburic in a monastery and ordered him a priest. This prevented him from regaining the throne. Next, Audeca married Siseguntia, King Miro's widow, and made himself king. This usurpation and the friendship granted by Eboric gave Leovigild King of the Visigoths the opportunity to seize the neighboring kingdom. 580: 585: During the 6th Century the Kingdom of Hispania became a formally declared kingdom identifying with Gallaecia when it was annexed by the Visigoths, and was turned into the sixth province of the Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania in 585. 585-711: The Kingdom of Galicia (Galician: Reino de Galicia, or Galiza; Spanish: Reino de Galicia; Portuguese: Reino da Galiza; Latin: Galliciense Regnum) was a political entity located in southwestern Europe. At its territorial zenith it occupied the entire northwest of the Iberian Peninsula. Founded by the Suebic King Hermeric in 409, the Galician capital was established in Braga. It was the first kingdom which adopted Catholicism officially and minted its own currency (year 449). The origin of the kingdom lies in the 5th Century, when the Suebi settled permanently in the former Roman province of Gallaecia. Their king, Hermeric, probably signed a foedus, or pact, with the Roman Emperor Honorius, which conceded them lands in Galicia. The Suebi set their capital in the former Bracara Augusta, setting the foundations of a kingdom which was first acknowledged as Regnum Suevorum (Kingdom of the Suebi), but later as Regnum Galliciense (Kingdom of Galicia).585: The Suebi maintained their independence until 585, when Leovigild, on the pretext of conflict over the succession, invaded the Suebic kingdom and finally defeated it. Audeca, the last king of the Suebi, who had deposed his brother-in-law Eboric, held out for a year before being captured in 585. This same year a nobleman named Malaric rebelled against the Goths, but he was defeated. After the temporal rule of the Visigothic monarchs (585-711), Galicia became a part of the newly founded Christian kingdoms of the Northwest of the peninsula, Asturias and León, while occasionally achieving independence under the authority of its own kings. 585: In 585 Leovigild King of the Visigoths moved war on the Sueves, invading Galicia. In words of John of Biclaro: "King Leovigild devastates Galicia and deprives Audeca of the totality of the Kingdom; the nation of the Sueves, their treasure and fatherland are conduced to his own power and turned into a province of the Goths." During the campaign, the Franks of King Guntram attacked the Septimania, possibly attempting to assist the Sueves. At the same time, he sent ships to Galicia. These were intercepted by King Leovigild's troops who took away their cargo and killed or enslaved most of their crews. The kingdom was then transferred to the Goths as one of their three administrative regions, Gallaecia, Hispania and Galia Narboniensis. Audeca was captured, tonsured, and ordered a priest. He was then sent into exile in Beja, in Southern Lusitania. In 585, Liuvigild, the Visigothic king of Hispania and Septimania, annexed the Kingdom of Galicia, after defeating King Audeca. Later, a pretender to the throne, Malaric, rebelled against the Goths and reclaimed the throne. He was finally defeated and captured by the generals of King Leovigild. They took him chained to the Visigothic king. Thus the kingdom of the Suebi, which incorporated large territories of the ancient Roman provinces of Gallaecia and Lusitania, became the sixth province of the Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo. 568-586.: King Leovigild of the Visigoth expelled the imperial civil servants and attempts to unify the Peninsula. This marked the end of the Roman Empire in Spain. 586: After the conquest, King Leovigild of the Visigoths reintroduced the Arian Church among the Sueves, but this was a short-lived. After his death in 586, his son Reccared openly promoted the mass conversion of Visigoths and Sueves to Catholicism. King Reccared's plans were then contested and confronted by a group of Arian conspirators. Its leader was, Segga. He was sent into exile to Galicia, after the amputation of his hands. The conversion culminated during the Third Council of Toledo, which counted with the assistance of seventy-two bishops from Hispania, Gaul, and Galicia. There 8 bishops abjured of their Arianism, among them four Suevi: Beccila of Lugo, Gardingus of Tui, Argiovittus of Porto, and Sunnila of Viseu. The mass conversion was celebrated by King Reccared: "Not only the conversion of the Goths is found among the favors that we have received, but also the infinite multitude of the Sueves, whom with divine assistance we have subjected to our realm. Although led into heresy by external fault, with our diligence we have brought them to the origins of truth". He was styled as "King of the Visigoths and of the Suevi" in a letter sent to him by Pope Gregory the Great soon thereafter. With this began the amalgamation of Roman and German elements in Spain. In law and politics the Romans became Gothic; the Goths in social life and religion became Roman. Soon the Catholic Church became the national church. Yet the connection with Rome ceased almost entirely. The court of highest instance was the national council at Toledo. The king appointed the bishops and convoked the council. But the constant struggles of the royal house with the secular and spiritual aristocracy would cause the downfall of the nation. 589: The government of the Visigoths in Galicia did not totally disrupt the society, and the Suevi Catholic dioceses of Bracara, Dumio, Portus Cale or Magneto, Tude, Iria, Britonia, Lucus, Auria, Asturica, Conimbria, Lameco, Viseu, and Egitania continued to operate normally. During the reign of Liuvigild, new Arian bishops were raised among the Suebi in cities such as Lugo, Porto, Tui, and Viseu, alongside the cities' Catholic bishops. These Arian bishops returned to Catholicism in 589, when King Reccared converted to Catholicism, along with the Goths and Suebi, at the Third Council of Toledo. The territorial and administrative organization inherited from the Suevi was incorporated into the new Provincial status, although Lugo was reduced again to the category of bishopric, and subjected to Braga. Meanwhile the Suevi, Roman, and Galician cultural, religious, and aristocratic elite accepted new monarchs. The peasants maintained a collective formed mostly by freemen and serfs of Celtic, Roman and Suebi extraction, as no major Visigoth immigration occurred during the 6th and 7th centuries. This continuity led to the persistence of Galicia as a differentiated province within the realm, as indicated by the acts of several Councils of Toledo, chronicles such as that of John of Biclar, and in military laws such as the one extolled by Wamba which was incorporated into the Liber Iudicum, the Visigothic legal code. It was not until the administrative reformation produced during the reign of Recceswinth that the Lusitanian dioceses annexed by the Suevi to Galicia (Coimbra, Idanha, Lamego, Viseu, and parts of Salamanca) were restored to Lusitania. This same reform reduced the number of mints in Galicia from a few dozen to just three, those in the cities of Lugo, Braga, and Tui. 590:

7th Century: 7th Century: A century later, the differences between Gallaeci and Suebi people had faded, leading to the systematic use of terms like Galliciense Regnum (Galician Kingdom), Regem Galliciae (King of Galicia), Rege Suevorum (King of Suebi), and Galleciae totius provinciae rex (king of all Galician provinces), while bishops, such as Martin of Braga, were recognized as episcopi Gallaecia (Bishop of Galicia). The most notable person of 7th Century Galicia was Saint Fructuosus of Braga. Fructuosus was the son of a provincial Visigoth dux (military provincial governor), and was known for the many foundations he established throughout the west of the Iberian Peninsula, generally in places with difficult access, such as mountain valleys or islands. The saint wrote two monastic rulebooks, characterized by their pact-like nature, with the monastic communities ruled by an abbot, under the remote authority of a bishop (episcopus sub regula), and each integrant of the congregation having signed a written pact with him. Fructuosus was later consecrated as abbot-bishop of Dumio, the most important monastery of Gallaeciafounded by Martin of Braga in the 6th Centuryunder Suebi rule. 600: 600: Around the year 600, the political map of southwestern Europe referred to three different areas under Visigothic government Hispania, Gallaecia, and Septimania 610:

620:

630:

640:

650: Mid-7th Century: Under the Goths, the administrative apparatus of the Suevi Kingdom was initially maintained many of the Suevi districts established during the reign of Theodemar are also known as later Visigothic mints but during the middle years of the 7th Century an administrative an ecclesiastical reform led to the disappearance of most of these mints, with the exception of that of the cities of Lugo, Tui, and Braga. Also the northern Lusitanian bishoprics of Lamego, Viseu, Coimbra and Idanha-a-Velha, in lands which had been annexed to Galicia in the 5th Century, were returned to the obedience of Mérida. It has been also pointed out that no visible Gothic immigration took place during the 6th and the 7th Century into Galicia. Last mention of the Sueves as a separate people dated to a 10th Century gloss in a Spanish codex: "hanc arbor romani pruni vocant, spani nixum, uuandali et goti et suebi et celtiberi ceruleum dicunt" ("This tree is called plum-tree by the Romans; nixum by the Spaniards; the Vandals, the Sueves, the Goths, and the Celtiberians call it ceruleum"), but in this context Suebi probably meant simply Galicians. Mid- 7th Century: From the middle of the 7th Century the Arabs (Moors) were masters of North Africa. A nomadic people from North Africa; the Moors were originally inhabitants of Mauretania 660:

680:

690: 8th Century King Witiza died in 710, leaving two young sons, for whom Witizas widow and family tried to secure the succession. But a faction of the Visigothic nobles elected Roderick and drove the Witizans from Toledo. The Visigothic state apparatus' disintegration allowed the Muslims to make isolated pacts with an aristocracy that was semi-independent and opposed to the Crown. Al-Andalus was a medieval Muslim cultural domain and territory occupying at its peak most of what are today Spain and Portugal (At its greatest geographical extent, in the 8th Century, southern France -- Septimaniawas briefly under its control.). The name more generally describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula governed by Muslims (Given the generic name of Moors) at various times between 711 and 1492, though the boundaries changed constantly as the Reconquista progressed. Following the Muslim conquest of Hispania, Al-Andalus was at its greatest extent. It was divided into five administrative units, corresponding roughly to modern Andalucía, Portugal and Galicia, Castile and León, Aragón, county of Barcelona and Septimania. As a political domain, it successively constituted a province of the Umayyad Caliphate, initiated by the Caliph Al-Walid I (711-750); the Emirate of Córdoba (c. 750-929); the Caliphate of Córdoba (929-1031); and the Caliphate of Córdoba's taifa (successor) kingdoms. Rule under these kingdoms saw a rise in cultural exchange and cooperation between Muslims and Christians, with Christians and Jews considered as protected people as long as they paid a tax to the state. With this they enjoyed limited "internal autonomy". The Moors (Iberian and North African Muslims) imported white Christian slaves into Muslim Spain in varying degrees from the 8th Century until the Reconquista in the late 15th Century. The slaves were exported from the Christian section of Spain, as well as Eastern Europe by slave traders, sparking significant reaction from many in Christian Spain and many Christians still living in Muslim Spain. 700: 700: The crisis at the end of the Visigoth era dates to the reign of Egica. On 15th or 24th of November, 700 A.D., Wittiza was anointed king; this forms the last entry in the Chronica Regum Visigothorum, a Visigothic regnal list. The monarch appointed his son Wittiza as his heir, and despite the fact that the Visigothic monarchy had been traditionally elective rather than hereditary Egica associated Wittiza during his lifetime to the throne (for example, Egica and Wittiza are known to have issued coinage with the confronted effigies of both monarchs). 701: In 701 an outbreak of plague spread westward from Greece to Spain, reaching Toledo, the Visigothic capital, in the same year, and having such impact that the royal family, including Egica and Wittiza, fled. It has been suggested that this provided the occasion for sending Wittiza to rule the Kingdom of the Suevi from Tui, which is recorded as his capital. The possibility has also been raised that the 13th Century chronicler, Lucas of Tuy, when he records that Wittiza relieved the oppression of the Jews (a fact unknown from his reign at Toledo after his father), may in fact refer to his reign at Lucas' hometown of Tui, where an oral tradition may have been preserved of the events of his Galician reign. 702: In 702, Egica died. His successor, Wittiza, as sole king moved his capital to Toledo. 710: 710: In 710, part of the Visigothic aristocracy violently raised Roderic King of the Visigoths to the throne. This triggered a civil war with the supporters of King Wittiza and his sons.711: In 711, the enemies of King Roderic invited a Muslim army to cross the Straits of Gibraltar and face him at the Battle of Guadalete. With his defeat came and end to Roderic and Visigothic rule. This was to have profound consequences for the whole of the Iberian Peninsula. 711: The Rise of Moors and Islam on the Iberian Peninsula began. 711: After the Christian Visigoths were defeated by the Moslem peoples of North Africa, the Arab and Berber invaders slowly pushed the Christians back toward the mountains of the north and northwest Spain.

The Emirate: (711 to 756) the Battle of Guadalete, the Arabs spread northward across the Pyrenees into France. However, they were driven back by Charles Martel and his Frankish knights in 732.

Berbers are Sunni Muslims. Their native languages are of the Hamitic group, but most literate Berbers also speak Arabic, the language of their religion. About 12 million people, not all of who are considered ethnic Berbers, speak Berber languages. Despite a history of conquests the Berbers have retained a remarkably homogeneous culture, which on the evidence of Egyptian tomb paintings, derives from earlier than 2400 B.C. The alphabet of the only partly deciphered ancient Libyan inscriptions is close to the script still used by the Tuareg. Until their conquest in the 7th Century by Muslim Arabs, most of the Berbers were Christian and a sizable minority had accepted Judaism. Many heresies of the early African church, particularly Donatism, were essentially Berber protests against Roman rule. Under the Arabs, the Berbers became Islamized and soon formed the backbone of the Arab armies that conquered Spain. However, the Berbers repeatedly rose against the Arabs. In the 9th Century they supported the Fatimid dynasty in its conquest of North Africa. After the Fatimids withdrew to Egypt, North Africa was plunged into anarchy. The warring of the Berber tribes ended only when the Berber dynasties, the Almoravids and the Almohads, were born. Each of these dynasties succeeded in pushing back Christian kingdoms, after they had pushed south against the fragmented Moors. With the disintegration of these dynasties, the Arabs gradually absorbed the Berbers of the plains, while those who lived in inaccessible mountain regions, such as the Aurès, the Kabylia, the Rif, and the Atlas retained their culture and warlike traditions. When the French and the Spanish occupied much of North Africa, it was the Berbers of these mountainous regions who offered the fiercest resistance. In more recent times, the Berbers, especially those of the Kabylia, assisted in driving the French from Algeria. In 711, African and Arab Muslims conquered the Iberian Peninsula and granted Jews Religious, though not complete economic or political, freedom. This began the period described as the "golden age" of Spanish Jewry which lasted roughly to near the end of the 14th Century. It saw the advancement of many Jews in instrumental roles as political advisers and physicians and the development of Sephardic Jewish traditions in poetry, Literature, philosophy, and biblical interpretation. Jews were active participants in Spanish society, and many felt that they were Spanish as well as Jewish. 711: In the 8th Century, the Kingdom of the Suebi or the Kingdom of Gallaecia in the mountains of Asturias (The old Suevian Kingdom) was a post-Roman Germanic kingdom. It was one of the first to separate from the Roman Empire. Based in the former Roman provinces of Gallaecia and northern Lusitania, the defacto kingdom was established by the Suebi about 410. During the 6th Century it became a formally declared kingdom identifying with Gallaecia, maintaining its independence until 585. It was then annexed by the Visigoths and was turned into the sixth province of the Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania. Resistance to the African Muslim invasion of the 8th Century was limited to small groups of Visigoth warriors who had taken refuge in the mountains of Asturias in the old Suevian kingdom, the least romanized and least Christianized region in Spain. Only there in the northern independent Christian kingdom of Asturias had Visigothic power survived. The Asturias is a land Area 10,565 square kilometers (4,079 square miles). Separated from its surroundings by the Cantabrian Mountains, the autonomous region of Asturias has traditionally managed to remain somewhat isolated and independent from the rest of Spain. The kingdom flourished until the 10th Century and later became the base for the Christian Reconquest of Spain. Reconquista: 711-1492 (8th-15th centuries) It is important to remember that once the Islamic hordes swept out of North Africa from across the Gibraltar straits, within seven years they had conquered all but the northwest Spanish coastal region. After the Christian Visigoths were defeated the African Arab and Berber invaders slowly pushed the Christians back toward the mountains of the north and northwest Spain. These same invaders marched across the Pyrenees into France until finally being halted by Christian warriors. Spain and all Christianity found itself under siege and warring with a fierce and well-trained army of religious fanatics bent on the complete destruction of Christian Europe. These Moors were a determined lot, who had entered Spain to stay and make vassals of the Iberian peoples of that day. Many believe that the Reconquista of the 8th-15th centuries, a sporadic and epic struggle between two religions and cultures, greatly impacted the Spanish Psyche. The commonly held idea of the Reconquista of Iberia by the Christian Kingdoms against the African Muslims as one single process spanning eight centuries is historically inaccurate. During the period the Christian realms in northern Spain and France warred against each other for the purpose of consolidation of power as much as against the Muslims for dominance and expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula (Spain). It should be noted that as modern citizens of nation-states, we find it difficult to understand such religious fervor. We view conflicts as disagreements between nations not personalities or religions. The fact remains that how we view a conflict and what actually underpins it are not necessarily based upon our understanding or logic. Religion can be a very powerful force and at times overshadows all other aspects of normal human disagreement. In fact, it can become the embodiment of those disagreements to the extent that it is the disagreement. This became the case on the Iberian Peninsula. African Islam made its way to European Iberia to dominate and replace Christianity. The Christian kingdoms rallied against overwhelming odds, fought for almost eight centuries, and were finally victorious over the African Moors. These Moorish invaders after conquering in the name of their prophet caused great bloodshed and brought their Middle Eastern culture to Spain. With their scientific knowledge of irrigation systems and methods, the Moors opened up once arid lands to agriculture and increased the food supply. They introduced new plants and new methods of agriculture. They also brought education, mathematics, science, and the arts that flourished in their newly founded kingdoms throughout Iberia. The Moors arrived with translations of the Greek masters (Archimedes, Pythagoras and the philosopher Ptolemy). They introduced a much better system of numbers derived from India via the Middle East and Alexandria, called the Hindu-Arabic number system. Algebra, originating in Babylonia and Egypt and later perfected by the Greeks where it was needed for constructing huge monuments was also re-introduced into Iberia by the Moors. Under the African Moors culture and architecture reached new heights; two of the greatest examples of these are the Alhambra in Granada and the Escorial in Córdoba. Their architecture and construction boasted magnificent mosques and palaces surrounded by beautiful gardens. The Moors valued learning. Spain under Moorish dominance was known for its literature, and science. They brought techniques of leather working, silk culture, and glass manufacture. But in return, they enslaved the Iberians. That slaves alone were used to build their monuments can only be answered with uncertainty. Trade ties between the Moorish kingdoms and the North African Moorish state led to a greater flow of trade within those geographical areas. The Iberian Peninsula served as a base for the export of slaves into other Muslim regions in Northern Africa. In addition, the Christian Iberians who lived within Arab and Moorish-ruled territories were not only subject to discriminatory laws and taxes, but were also coerced into Islamic faith. The Moors also engaged large sections of Spaniards and Portuguese Christians as slave labor. It should be remembered that at this time less than one percent of the Iberian population was Moor. More than ninety-nine percent were native Iberians. And yet one twelfth of the Iberian population was composed of European slaves. Yes, the Moors utilized ethnic European slaves. This was a result of periodic Arab and Moorish raiding expeditions sent from Islamic Iberia to ravage the remaining Christian Iberian kingdoms, bringing back stolen goods and slaves.