| d |

THE YOUNG WIDOW

After the attack off the Santa Barbara coast, and Los Angeles skies,

Dad moved us to Ontario. We rented a house which backed to the

grammar school. We

had lots of freedom to wander around. Ontario has a lot of orange

orchards. Being resourceful we would gather oranges that had fallen to

the ground and sell them from door to door.

One of these doors, was to a unit in a little wooden

four-complex, opened by a young woman. She was married;

she had a ring on. She seemed very sad and wanted to talk, even to us

kids. She moved there to be closer to the base where her husband was

stationed. She didn't know anyone. It was not home. After paying us

for the oranges, she went in the bedroom and came out with a box. The

box was filled with lingerie sets. You could see all the items were

new, beautiful, silky, lacey, in many delicate colors.

Then quietly she started handing them to us, giving them to us.

We were four. She emptied the box. We were giddy. We felt like

princesses and wore the sweeping items over our

clothes.

Mom was very, very upset. She could see the quality and that they were

new. She wanted us to take them back. Unfortunately, we really had no

idea where we had been.

Eventually

the excitement were off, and I don't really remember what happened to

those beautiful emblems of femininity. What I do remember was young

woman's intense sadness and the picture of a soldier in uniform on the

side table.

I also

remember that she begged us to come back and visit her, but we never

did. I always felt bad about that, even more so when I grew up and put

all the pieces together.

The scenario: She had recently gotten word that her husband was not

coming home. He had died in battle. The beautiful lingerie that she

was planning to model for him was a painful future that was not to

be.

LIVING IN A JAPANESE HOUSE, a barn and a pond.

Soon after returning to Los Angeles,

I was sent to

to stay with my Valdez cousins while Mom and Dad made a trip to San Antonio

to attend a family funeral.

It seemed a little

strange that the house that my Valdez

cousins lived in, in Stockton, was being rented from a Japanese family.

The family was interned, and had made an agreement with the Valdez

family, trusting their home, house and belongings to their care. The house had

a big barn and it was filled with furniture, stacked quite high,

almost to the ceiling and covered with heavy rugs.

My cousin Alba (two

years younger than me), and I were told not to touch anything in the

barn and not

to climb on anything in the barn. We did not, but I wondered how

it must have felt to leave everything, in the care of strangers.

My cousin Alba

remembers, we did not climb on the

top of the barn. We did peek under

the ends of the rugs, and climbed on the top of the barn. She recalled

we were

thinking of some interesting ways of getting down without a ladder,

superman capes. Fortunately we were stopped before we tested it out.

Also on the

property was a pond, a Koi Fish Pond. Of course we kids had no sense of

the value of the fish; however, we surely did appreciate how beautiful

they were, lots of bright colors, oranges, yellows, reds and spots of

white. They were quite large, maybe 8 inches and longer.

We would wade in

the pond and the fish would swirl around our feet. They did not seem

to mind us. I guess one of the adults in the house was taking good care

of them because I don't recall any Koi dying. Perhaps it

was Abuelito or Abuelita Chapa. They moved out of Los Angeles and were staying with

the Valdez family too. Grandma

seem to have a connection with nature, and grandpa was just smart in

everything.

A LESSON ON BASIC ECONOMICS . . .

My grandpa,

Abuelito Alberto Chapa taught me a lesson that I will never forget. He

had been an educator in Mexico, Superintendent of Schools in Sabinas

Hidalgo, Nuevo Leon. I am sure this lesson was intentional, as

his action usually was, but more indirect . . . .

not like the very direct, knuckle-knock on the head, with the

"No seas tonta." comment.

|

No, this was special. Grandpa would occasionally giving my cousin

Alba and me a nickel, to get an ice cream cone on the way

home from school.

One Monday however, he surprised us, and instead of the nickel,

he gave each of us quarter, accompanied by a sly smile. I think

now . . .he was testing us. He thought (maybe hoped)

that we would have enough sense to spread out the 25 cents, and enjoy

a cone every day. Instead, standing in the ice cream

parlor and looking at all the flavors, Alba and I decided to splurge and get a

Five-Decker ice cream cone. We were ecstatic. We could get all the

colors. The colors were just as bright as these scoops,

but as I remember they almost all tasted the same.

By the time

we got home, in the Stockton heat, ice cream was running down our arms,

dripping on our cloths, and leaving a tell-tale trail of ice cream on

the sidewalk, a tale of our foolishness. Grandpa saw us come in.

He didn't say a word, he just looked at us and went into the other room. We both thought he

was mad at us, but years later I realized, he probably went into the

other room to muffle a laugh.

It was a financial lesson, I never forgot. Even

if you have the money there's no need to be stupid about how you spend

it. Think ahead!!

|

GERMAN

PRISONERS OF WAR IN OUR BACKYARD

A couple of years later I was again sent up to be with the Valdez

family. Uncle Gilbert and Aunt Elia had bought a house in North

Stockton. I remember several times going on walks with Tia passing a

fenced-in area, with a high wire fence surrounding it.

Tia said they

were German soldiers, prisoners of war. I looked at the open, sunny

well manicured acreage, the men looked healthy, well fed and doing

some light gardening. One of the prisoners called us over to the

fence. He and Tia started talking, quickly a guard came over,

and firmly, but politely directed us not to talk to the prisoners. The

man seemed lonely.

However,

they

were prisoners,

but as we walked away I could not help but contrast,

the conditions of the German concentration camps with the emaciated,

starving people stuffed into airless, sunless housing, seen in the

news-reels, with the condition of these German prisoners. These

men looked like they were enjoying a day at the park.

It was quite evident that they were the fortunate, to have been caught

and brought to the United States.

I wondered how my uncles, Albert and

Oscar were doing? What were the conditions they were living

under?

I

was especially close to two of my young uncles.

My uncle Oscar who as a 10-year-old was working in a car garage, was

quickly identified for his mechanical knowledge and skill. He started

the war serving in the Army and finished the war as a Master Sergeant

in the Air Force, responsible for the maintenance of all the aircraft

at his base.

My uncle Albert went into the Marines and fought in the South Pacific.

He did not speak much about his experiences serving there, except

once, He said, the greatest pain was to hear the screams of their

buddies being tortured by the Japanese. He said the

Japanese would wait to inflict the pain at night, so the sounds would

be heard better. Al said it drove some of the men crazy, literally.

He said one time, he was walking through the jungle, rifle raised,

finger on the trigger when he suddenly came face to face with a

Japanese soldier in the same posture. He said, we looked at each

other in the eyes, locked as statues in time, realizing what the next

second could mean. In a moment of two, we each dropped our rifle just

a little bit and slowly walked away backwards. Gratefully,

Tio came home, with two Purple Hearts, alive, and only part of a

finger missing.

The war was over in the spring of 1945. That fall

I started the 7th grade at Hollenbeck junior high in East

Los Angeles, war memories were still fresh.

And the evidence

seem to linger in various ways. Men were coming home. More Gold Stars

were hanging in windows. Crippled man were not so unusual anymore. We

were grateful. As a nation we were grateful, but the heavy cost was

evident.

STARTING HOLLENBECK JR. HIGH

|

Hollenbeck Junior High School

When I attended in 1946-47, the entire school was

enclosed with a very high wire fence.

Gates were kept locked and monitored for entering.

Everyone had to have an ID, or permission.

|

Evergreen

Elementary school was single story, neighborhood school with 12

classrooms, students moving up every half year. The

student body was about 150.

Hollenbeck Junior High's main building is a three-stories, with a

gymnasium, shop, and cafeteria. It was quite a contrast to

Evergreen, with Hollenbeck Junior High, whose current student body is

listed as 1176. I remembered it was hundreds, hundreds.

Lots and lots of kids, mostly taller!!

Junior high

required trying to maneuver around physically, and understand social rules beyond " la familia

" and grade school. The first incident as a freshman was realizing that old

friends might have new alliances.

Freshman were instructed to meet in

the gymnasium. There were a hundreds of us freshman.

I was really relieved when I saw Olga. Olga was the only other

Mexican in my class at Evergreen, I smiled and waved. But Olga did not smile back and

turned away when I walked towards her. She was with a group of

girls. I was confused and puzzled. We played together.

For our 6th grade graduation, we performed a Mexican dance together. The

families even got together. We were about the same size. We

frequently wore our hair the same way, in braids. but I was fair with

green eyes and she was brown-skin with dark eyes. The two girls

standing on either side of Olga had her coloring too. She seemed to be

a little afraid to greet me, and walked away between the two girls, in the middle of a large group.

I stood alone wondering what had happened.

Home rooms were assigned with some orientation information. We

found our ways to our homeroom, meeting the

teacher, introducing ourselves. It appeared that students

from all the different elementary schools were purposely put into home

rooms where they would be encouraged to make new friends, because no

one seemed to know anyone.

My way of

starting a conversation was asking what elementary school they went

to. The answer that affected me the most was when the girl sitting

next to me, softly answered, "I didn't. I was in an internment

camp." Even though I could see she was Asian, I had not put the

pieces together. I just saw her as me, another new freshman.

Hollenbeck

was a fresh new world. Looking around me, I could the results of

see lots of war in the students. Different people, from

countries like Yugoslavia, Latvia, Lithuania, with surnames and

accents that I had never heard. Most immigrating from those

countries were Jews, fleeing both the Germans and Russians who

continued to track down Jews, enslaving or executing them.

We also had students who were from Rumania, also considered inferior

by Hitler. On those occasions when we had to walk to school, we

passed the homes of gypsies. Their homes were rented stores with

blankets covering the glass display case for privacy. The women

sat outside, with long skirts and scarves on their heads looking very

mysterious. Their small children playing on the

sidewalk.

We had

American families whose English also sounded a little different. They

were disparaging referred to as "Oakies" who were fleeing

the damage of the lifeless dust bowl areas. Another

group were the Mexican pachucos. The girls with their high

Pompadour's, short skirts, heels, and make-up, who to me seemed so

sophisticated. The boys wore oversized shirts and slicked back hair.

We also had a large population of African-American students.

Hollenbeck took pride in being the most ethnically mixed school in Los

Angeles. We had a

map in the office with flags stuck on it representing all the

countries represented by our student population.

In addition

to the mixed nationalities, student life was further

complicated with the forming of clicks and gangs, somewhat based on

where you lived. Although I joined a group, a club, I tried to keep a

relationship with everyone. To avoid the complicated junior-high

social scene of who sits were, who is mad at who, and general gossip,

etc., I volunteered to work in the front office during the lunch

period.

|

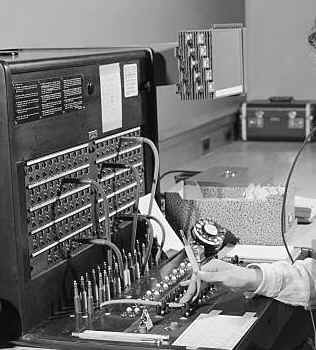

It was quiet and I

was learning new skills, such as running a telephone switchboard,

answering the phone, learning to take messages, feeling comfortable

talking to authorities. It was fun. The challenge was to match

both sides correctly. I was taking college prep

classes. For my electives, continuing my interest in theater, I took

choir, public speaking, and drama. Sometimes,

with no tasks, I could use that time to do some homework. All in

all, it was a peaceful time in the middle of the day.

One day, I actually helped an FBI agent, who was trying to reach a

student for questioning. I did have a few few oops,

connecting the wrong people or disconnecting or disrupting a

conversation, like with the principal, which I did a few times.

As I reflex

back on the wisdom of the homeroom system, the value of making friends with people

not of your ethnic group, heritage, or race, became very clear.

It was a wonderful preparation for life.

|

Because I worked in the office, I was allowed to leave class a little

bit early to get my lunch in the cafeteria. One day an

African-American girl blocked my way into the cafeteria. She was holding the door

shut and would not let me enter. I explained the situation through the

door, but she would not budge. Suddenly, Martha, an African-American

girl my homeroom, came over, bumped her out of the way and open the

door for me. I turned to thank her, but Martha did not look at me, or

speak to me. I was puzzled. Martha took care of it, then and

quietly too because I never

had a problems getting into the cafeteria early again.

I wondered why I had never had a problem with any

Mexican groups trying to recruit me. I thought maybe more than just my

color, it was because I was taking college prep classes, and there

were very few Mexican heritage students in the college prep classes. I

remember one other Mexican in the college prep classes. I believe his

name was Rudy Medina. Years later I recognized him on a PBS station.

He as an educator with the Los Angeles Unified School District

involved in producing educational videos.

I also thought, maybe I wasn't approached because of my

sister. My sister, Tania was a half a year ahead of me, and six inches

taller. She was an outstanding athlete. Tania won the athlete of year

award when she graduated.

Wondered if it was something with my "star

status". I tried out and got a singing solo in the school talent

show. I sang A Sleepy Lagoon. Looking back on the staging, I think I

solved why the spotlight light on me was so dim, almost dark. I wasn't

sure anyone could actually see me, which as I reflect on the situation

was probably the intent. I was small, and physically undeveloped, but

had a a full and powerful voice. Mom said some of the students who

went by my Dad's cleaning/tailoring shop, thought I was just

lip-sinking. My Mom said, she had to convince them that it was really

me. They didn't believe it. The music director knew what she was

doing. Was that really little Mimi Lozano singing?

For the Christmas

program, the setting was very different. I was not

hidden, with no lights. In fact she placed me, in what I

would call center stage.

We were about 40-50 in the choir/glee club. We were five rows,

one on the floor, four bleachers, and me, by myself on the top

row. I was at the top of the people /student pyramid.

We were all dressed in costumes of our

different family ethnicities. I was dressed in a Mexican

outfit and assigned to sing the solo part, in a sweet little

Mexican children's song, "A la Puerta del Cielo,

Venden Zapatos".

A few years ago, I tried to locate the song, with no luck, but

this time, I found it immediately. It is a traditional

Mexican Christmas song and lullaby,

which originated in Spain in the 16th century:

https://www.mamalisa.com/?t=es&p=3027

Hear different youth groups sing the song.

|

|

A la puerta del

cielo

Venden zapatos

Para los angelitos

Que andan descalzos

Duérmete niño

Duérmete niño

Duérmete niño

Arrú arrú

A los niños que duermen

Dios los bendice

A las madres que velan

Dios las asiste

Duérmete niño

Duérmete niño

Duérmete niño

Arrú arrú |

At the gates of

heaven,

They sell shoes

For the little angels

That go barefoot.

Sleep baby,

Sleep baby,

Sleep baby,

Hush-a-bye now.

The children who sleep,

God bless them.

The mothers who watch,

God helps them.

Sleep baby,

Sleep baby,

Sleep baby,

Hush-a-bye now.

|

When I

graduated from Hollenbeck into Roosevelt High School, I

heard a rumor, adding to the "safe social cocoon" which I

had enjoyed. I was told that the word was that one of the leading Pachucas

at Hollenbeck Junior High had spread the word to leave me alone.

Like Martha, she was also in my homeroom. We sat next to each other

and and frequently shared stories. Apparently, she protected me like Martha had, quietly. After my experience with Olga, I never made a

show of saying hello to my Pachuca friend on the grounds, when she was with a bunch

of her friends. I avoided eye-contact, and respected that she did not

want to acknowledge me, but in class we spoke freely.

She seemed very comfortable with me, and me with her.

Interesting in a life-view, that in spite of not belonging to any Mexican gangs

during Junior High, it was a gang fight that actually came close to taking my

life.

For some reason on this particular day, I was walking home

from Hollenbeck by myself; usually my sister and

I walked home together. The route passed Roosevelt High, which is

very close to Hollenbeck. I was standing on the

corner waiting for the red light to change when I became aware that to my

right a large gang of Latinos were heading towards me, towards

Roosevelt High. They were looking past me. I turned to see where they

were looking and saw another Latino gang, approaching from the left

side of me.

Suddenly I

heard a cracking sound, almost simultaneously felt a wisp of air pass my right cheek

and heard a thud in the wooden post of the electric street light that I was

standing next to. Instantly both groups started yelling and everyone

started scattering in all directions.

I think I was a little bit in

shock, because, I just stood there. Stunned, I realized at that moment that I had been standing in the middle

of a war zone. When I looked at the lamp post, I saw clearly the

small round metal circle, the back of a bullet, imbedded in the wooden

post of the electric street light. The bullet had barely missed me. I often wonder how quickly life can

change, from one moment to the next.

Although, I came within inches of being killed, I don't think I

was the target. I think it was by chance that I was there, and was glad to

realize that at least, at that hostile encounter, like with my uncle

Albert, no one was hurt, including

me.

|