|

Jewish history abounds with strong Jewish women who ensured the survival

of the Jewish people.

Here are the brief, but remarkable stories of Jewish women whose legacies continue to shape us

today.

Queen Esther

Queen Esther, the famous heroine of the Purim story, was a Jewish orphan

selected by King Achashveirosh to be his wife as he ruled over a mighty

empire centered in ancient Persia. When the kings wicked minister Haman

proposed murdering the Jews, it was Esther who intervened, at great risk

to her life, begging the king for mercy on her people.

Theres a lot that people didnt know about Queen Esther. For one, her

name wasnt Esther. It was Hadassah, but she took the more

Persian-sounding name as her public face. When Esther was chosen to be

queen, she thought it prudent to reveal as little about herself as

possible. Her new husband was brutal and had recently murdered his first

wife, Vashti. Yet Esther, alone in the palace, never forgot who she was.

Jewish tradition teaches that Esther ate only seeds and legumes, cooked

in her own private kitchen, so she would never violate the laws of

kosher food. She secretly counted the days, keeping track of when it was

Shabbat each week.

Perhaps it was this steely determination that gave Esther the courage to

confront King Achashveirosh after he signed an order to murder all the

kingdoms Jews. Turning to her Jewish community outside the palace

walls, Esther asked that every Jew fast and pray for her success. Then,

she gathered up her courage and risked the kings wrath and certain

death by entering his chamber unbidden. Avaditi, avaditi she told her

uncle Mordechai: if I perish, I perish. Esther knew that some things are

worth risking all.

Sarah Schenirer

Sarah Schenirer was born in 1883 in Krakow, Poland, into a Chassidic

Jewish family. At that time, the expectation was that Jewish boys would

learn about their religion in special Jewish schools, and that Jewish

girls would attend publich schools and be instructed in Jewish thought

at home by their parents. This model may have worked in previous

generations, but Sara Schenirer saw firsthand how Jewish girls were

becoming woefully ignorant of Jewish topics and starting to assimilate.

She saw a crisis arising.

Sarah Schenirer was born in 1883 in Krakow, Poland, into a Chassidic

Jewish family. At that time, the expectation was that Jewish boys would

learn about their religion in special Jewish schools, and that Jewish

girls would attend publich schools and be instructed in Jewish thought

at home by their parents. This model may have worked in previous

generations, but Sara Schenirer saw firsthand how Jewish girls were

becoming woefully ignorant of Jewish topics and starting to assimilate.

She saw a crisis arising.

Sarah herself left school at 13 and became a seamstress. Unlike many of

her peers, she continued to read Jewish books and educate herself about

Judaism and Jewish thought. As girls went to her to commission new

clothes and for fittings, Sarah began to wish she had a way to show her

clients the beauty of their heritage. Older girls merely mocked her, so

Sarah decided to start educating young children and dreamed of opening a

Jewish girls school.

She went to visit the Belzer Rebbe, the spiritual leader of Sarahs

community, to seek his blessing. Many thought she would fail: she was

divorced and had no children of her own, and she was proposing something

radical that even the greatest Jewish leaders of her time had failed to

enact. The Rebbe, however, offered her two powerful words: Beracha

vhatzlacha - Blessings and success. In 1917, Sarah Schenirer opened a

school with 25 pupils called Beis Yaakov.

Soon, other towns were contacting Sarah asking for help in opening their

own Beis Yaakov schools for girls. By 1937, two years after Sara

Schenirers death, there were 248 Beis Yaakov schools educating 35,000

girls. Today, Beis Yaakov schools continue to thrive the world over. In

Israel alone, there are over 100 Beis Yaakov schools, educating over

15,000 girls and Sarah Schenirer is universally recognized as a

visionary educator who saved the Jewish people.

Hannah Senesh

Born into an assimilated Jewish family in Budapest in 1921, as a child

Hannah Senesh was drawn to Zionism and local Zionist youth group

activities. When she was 18 she made aliyah (moved to what would soon be

the state of Israel), settling in Kibbutz Sdot Yam, where she wrote

poetry and a play about kibbutz life.

Born into an assimilated Jewish family in Budapest in 1921, as a child

Hannah Senesh was drawn to Zionism and local Zionist youth group

activities. When she was 18 she made aliyah (moved to what would soon be

the state of Israel), settling in Kibbutz Sdot Yam, where she wrote

poetry and a play about kibbutz life.

In 1943, with World War II raging, Hannah volunteered for the British

Army, which presented her with a grave proposal: would she be willing to

parachute into Nazi-occupied Europe in order to help Allied efforts to

organize local anti-Nazi resistance movements? Hannah agreed and became

one of 33 soldiers chosen for this top-secret, dangerous mission. In

March 1944, she was dropped into Nazi-controlled Yugoslavia, where she

fought with Titos resistance troops for three months. She then crossed

the border into her native Hungary, where she was caught almost at once.

Viciously tortured over a period of months by the Hungarian police,

Hannah refused to give any details about her mission. On November 7,

1944, at the age of 23, Hannah was executed by firing squad. She refused

an offer to be blindfolded, staring clear-eyed at her murderers instead.

After her death, the following poem was found in her prison cell:

One, two, three

Eight feet long

Two strides across, the rest is dark

Life is a fleeting question mark

One, two, three

Maybe another week

Or the next month may still find me here,

But death, I feel, is very near.

I could have been 23 next July

I gambled on what mattered most, the dice were cast. I lost.

In 1950, Hannah Seneshs remains were returned to Israel and buried on

Mount Herzl in Israel. Many of her poems, as well as the diary she kept,

are classics in Hebrew literature today.

Dulcea of Worms

Much of what we know about Dulcea, a Jewish woman who lived during the

Middle Ages in the German city of Worms, comes from the poetry of her

husband, Rabbi Eleazar ben Judah of Worms (1165-1230). Her

accomplishments and character traits convey a picture of a remarkably

active community leader, leading a thriving Jewish community against the

background of the reign of terror of the Crusades.

Dulcea supported her family and community in one of the only means of

business open to Jews at the time: moneylending. Dulcea managed her

communitys resources, taking charge of neighbors funds and investing

them jointly at the most profitable rates. It wasnt her unusual

business acumen that impressed others, however, as much as her intense

spiritual life.

Following the devastation of the First Crusade of 1096, which saw the

brutal murder of thousands of Europes Jews, Dulcea and her husband

became members of an intellectual group that studied and penned Jewish

texts. Dulcea taught women and helped them express their spirituality.

As well as business enterprises, Dulcea was an accomplished craftswoman

and embroiderer. She sewed books and did the needlework required to join

panels of vellum to create forty Torah scrolls. She was also a

matchmaker and helped Jewish brides prepare for their weddings, and

performed tahara, bathing the dead and preparing the deceased for

burial.

Dulcea was murdered, along with her daughters Bellette and Hanna, in

November 1196, when two armed men broke into their home, attacking the

family, as well as a teacher and a number of students who were staying

with the family at the time. Dulceas husband survived the attack and

wrote about it for posterity. Though he didnt write that the attackers

were Crusaders, many historians have posited that it might have been

errant Crusaders who attacked Dulcea, perhaps because they knew of her

money lending activities and hoped to find treasure in her home.

Deborah

In the time of Judges in ancient Israel, Deborah was a prophet and a

leader, a military strategist who helped Israel fight and prevail

against the repressive Canaanite king Yavin. While there are seven

female prophets in the Torah, Deborah stands alone as a female military

leader in ancient Israel. The Torah describes her in impressive terms:

Deborah was a prophetess, a fiery woman; she was the judge of Israel at

that time (Judges 4:4).

The Torah records that Deborah sat in judgment under a palm tree, and

everyone who had disputes would bring them to her to adjudicate. Jewish

tradition gives some clue as to why Deborah was seen as such a

remarkable judge. She was a learned woman, yet her husband, Lapidot, was

an unlearned, simple laborer. Deborah longed to elevate her husband, and

she did so in an unusual way. Seeing that he was skilled at making wicks

for oil lamps, Deborah encouraged Lapidot to bring some of his wicks to

a place of worship in the town of Shiloh and donate them for holy use

there. She didnt urge him to do anything very different or make radical

changes in himself. Instead she identified what his strengths were and

encouraged him to make the most of them.

Under her guidance, Lapidot began to make innovation in his wicks,

boosting the light at the sanctuary in Shiloh. Deborah skillfully

encouraged her husband to maximize his best qualities, and put them to

ever higher use. This was the wisdom of her judgment: discerning the

strength inside people and encouraging them to use them for good.

Shlomtzion, Queen Salome Alexandra

The fact that Queen Salome Alexandra was called Queen at all was

controversial: her husband, Judah Aristobulus I, led the Jewish people

during a tumultuous period of internecine fighting and strife in the

First Century BCE. He was the first leader of Israel since the

destruction of the First Temple to claim the title King for himself.

When Judah Aristobulus died, Salome married his brother, Alexander

Jannai, a cruel and wicked ruler.

For years, Alexander Jannai was absent, off fighting in foreign wars,

and Queen Salome ruled in Israel alone, a wise and judicious ruler. She

removed blasphemers from positions in her government, replacing them

with the greatest rabbis and scholars of the day, including her brother,

Rabbi Shimon ben Shetach. Rabbi Shimon, along with Rabbi Joshua ben

Gamla, instituted a rule that became a model of Jewish life for

thousands of years, mandating that each town and city set up Jewish

schools to educate all the local children, educating poor children for

free if they could not afford tuition. So popular was Salome that she

soon became known as Shlomtzion, or Peace of Zion.

Alexander Jannai did return to Israel and took power from his wife. He

used his time in power to reverse many of her progressive decrees and

put hundreds of Jewish scholars to death. After Alexander Jannai died at

the age of 76 BCE, Queen Salome regained power and ruled for a further

nine years until her death in 67 BCE. She strengthened Israels

military, built fortresses, and Jewish tradition recalls her reign as a

time of peace and prosperity, when the crops were miraculously abundant

and prosperity reigned.

Sarah Aaronsohn

Sarah Aaronsohn was part of a large family that escaped anti-Semitic

persecution in Romania by moving to the land of Israel, settling in and

helping to build the nascent Jewish town of Zichron Yaakov in Israels

north. Sarah was born there in 1890, and grew up cultured and educated,

fluent in several languages; she was also an accomplished rider and a

skilled shooter. Her older brother Aaron became one of the worlds

foremost agronomists, and Sarah often accompanied him on trips to gather

plant samples and help him with his research.

During her childhood, the Ottoman Empire ruled over what is present-day

Israel, and the local authorities were ill-disposed towards Jews, making

life as difficult and possible for the Jewish community there. As an

adult, Sarah got an even more visceral insight into the cruelties of the

Ottoman Empire. Travelling by train from Istanbul to Zichron Yaakov in

1915, she saw first-hand the violence in what would soon become the

Armenian Genocide, in which one million men, women and children were

murdered by Ottoman forces.

By then World War I was in full force, with Turkey fighting on the side

of Germany. Sarah Aaronsohn was convinced that if they won the war,

Turkey would kill the regions Jews, just as they had murdered their

Armenian minority. Sarah, her brother Aaron, their siblings and some

friends decided to form a secret espionage network to spy on Turkish

military movements and relay information to Britain. They named their

group NILI, an acronym for Netzach Yisrael Lo Yeshaker, The Glory of

Israel Does Not Deceive (I SAmuel 15:29). Soon, NILI was the largest

pro-British spy ring in the entire Middle East.

Unsuspected by Turkish authorities, NILIs young members took note of

troop and ordinance information and sent encoded messages to British

forces. When her brother Aaron left to aid the British in Egypt, Sarah

took over NILI, running the spy ring from her familys home. In 1917,

one of NILIs secret messages was intercepted by Ottoman authorities.

Sarah refused British advice to leave and save herself, and remained in

Zichron Yaakov. She was arrested on October 1, 1917, and brutally

tortured for five days. She refused to divulge the identities of other

NILI members.

Finally, on October 6, 1917, Sarah was told she was to be transferred to

Damascus for yet worse torture. Fearing she might break down and betray

her fellow spies, Sarah asked for permission to return home one last

time. As she was led down Zichron Yaakovs main street, she sang a song

about a little bird flying away: a secret message to her fellow NILI

spies that their ring was broken. Once in her house, she secretly

removed a hidden pistol from its hiding place in the wall, locked

herself in the bathroom, and shot herself.

Following Britains victory in World War I, Britain formally thanked

NILI, saying that without their activities, Britain would not have been

able to win the war.

by Dr. Yvette Alt Miller

Aish.com

http://www.aish.com/jw/s/Queen-Esther-and-6-Other-Extraordinary-Jewish-Women.html?s=mm

|

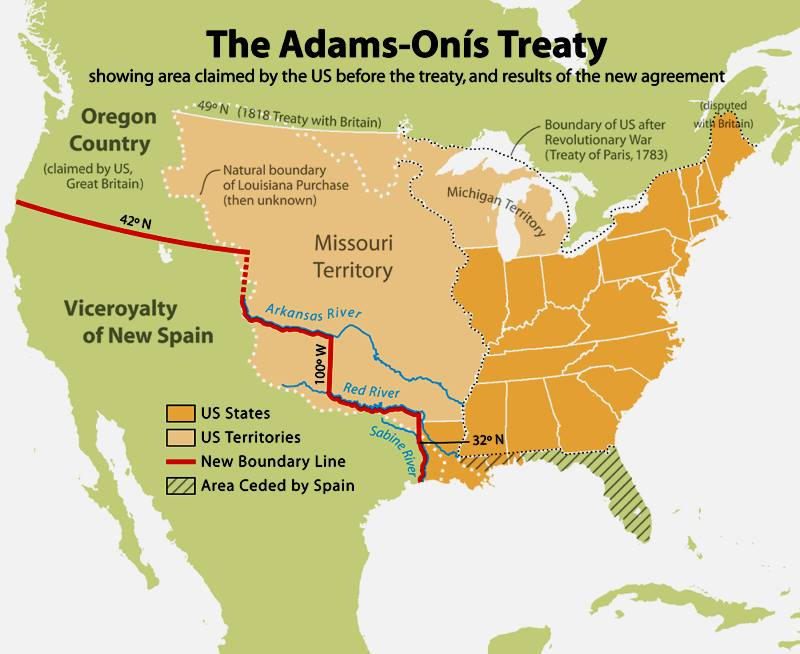

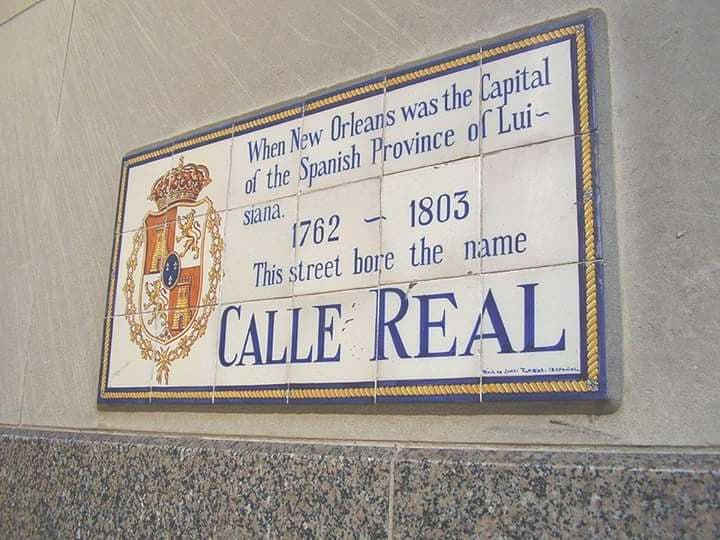

Aprovechando estos acontecimientos EEUU ordenó una

invasión terrestre y marítima para apropiarse de la

Florida. En septiembre de 1817, un gran despliegue

militar estadounidense apoyado con tropas españolas

procedentes de La Habana, desembarcó en Amelia y de allí

se dirigieron a Fernandina para someter a los rebeldes

que defendían la insurgencia en la Florida. En 1818,

EEUU intervino en la Florida Oriental y la presencia

española en La Florida tocaba a su fin tras el inicio de

negociación, del "Tratado Adam-Onís de 1819" por el que

España se vio forzada a vender las dos Floridas al

gobierno estadounidense a cambio de preservar sus

fronteras en el oeste norteamericano y 5 millones de

dólares. La anexión estadounidense del territorio

terminó finalmente en 1821 cuando el gobierno liberal

que había derrocado a Fernando VII ratificó el tratado,

año que marcó la intensificación de la guerra contra las

tribus seminolas que habitaban la península para

establecer colonos estadounidenses y conformar lo que es

hoy el Estado más meridional de los EEUU. Florida se

convirtió en el estado número 27 de los Estados Unidos

de América el 3 de Marzo de 1845. La mayoría de la

población española en la Florida emigró hacia Cuba y la

huella española acabó disolviéndose, siendo hoy escasa y

reflejandose solo en iglesias, edificios gubernamentales

o fortalezas, pero apenas en población.

Aprovechando estos acontecimientos EEUU ordenó una

invasión terrestre y marítima para apropiarse de la

Florida. En septiembre de 1817, un gran despliegue

militar estadounidense apoyado con tropas españolas

procedentes de La Habana, desembarcó en Amelia y de allí

se dirigieron a Fernandina para someter a los rebeldes

que defendían la insurgencia en la Florida. En 1818,

EEUU intervino en la Florida Oriental y la presencia

española en La Florida tocaba a su fin tras el inicio de

negociación, del "Tratado Adam-Onís de 1819" por el que

España se vio forzada a vender las dos Floridas al

gobierno estadounidense a cambio de preservar sus

fronteras en el oeste norteamericano y 5 millones de

dólares. La anexión estadounidense del territorio

terminó finalmente en 1821 cuando el gobierno liberal

que había derrocado a Fernando VII ratificó el tratado,

año que marcó la intensificación de la guerra contra las

tribus seminolas que habitaban la península para

establecer colonos estadounidenses y conformar lo que es

hoy el Estado más meridional de los EEUU. Florida se

convirtió en el estado número 27 de los Estados Unidos

de América el 3 de Marzo de 1845. La mayoría de la

población española en la Florida emigró hacia Cuba y la

huella española acabó disolviéndose, siendo hoy escasa y

reflejandose solo en iglesias, edificios gubernamentales

o fortalezas, pero apenas en población.

So

here we are on a bus with a bunch of soldiers from Fort Shafter and I am

sitting alongside a old time sergeant.

So

here we are on a bus with a bunch of soldiers from Fort Shafter and I am

sitting alongside a old time sergeant.

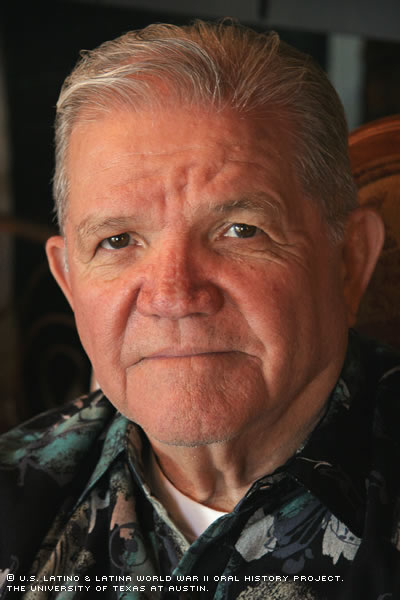

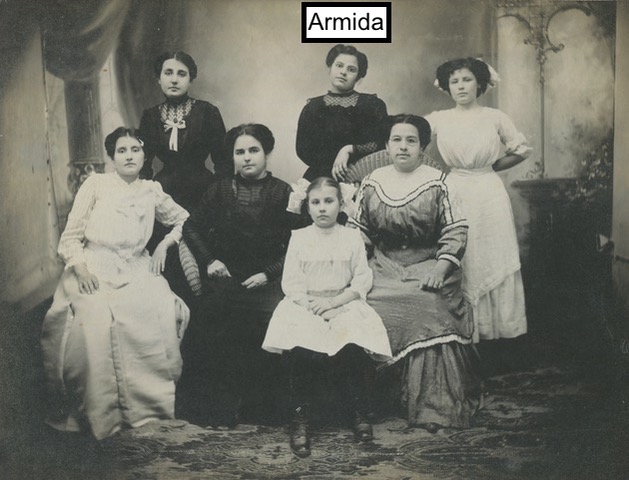

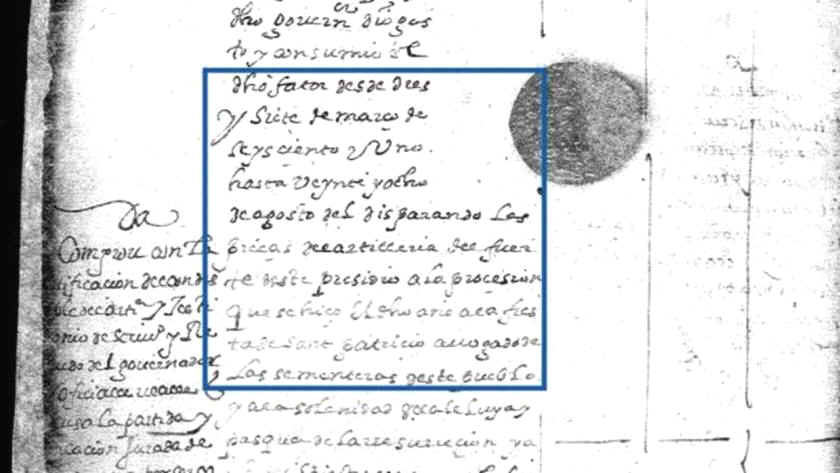

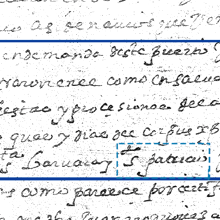

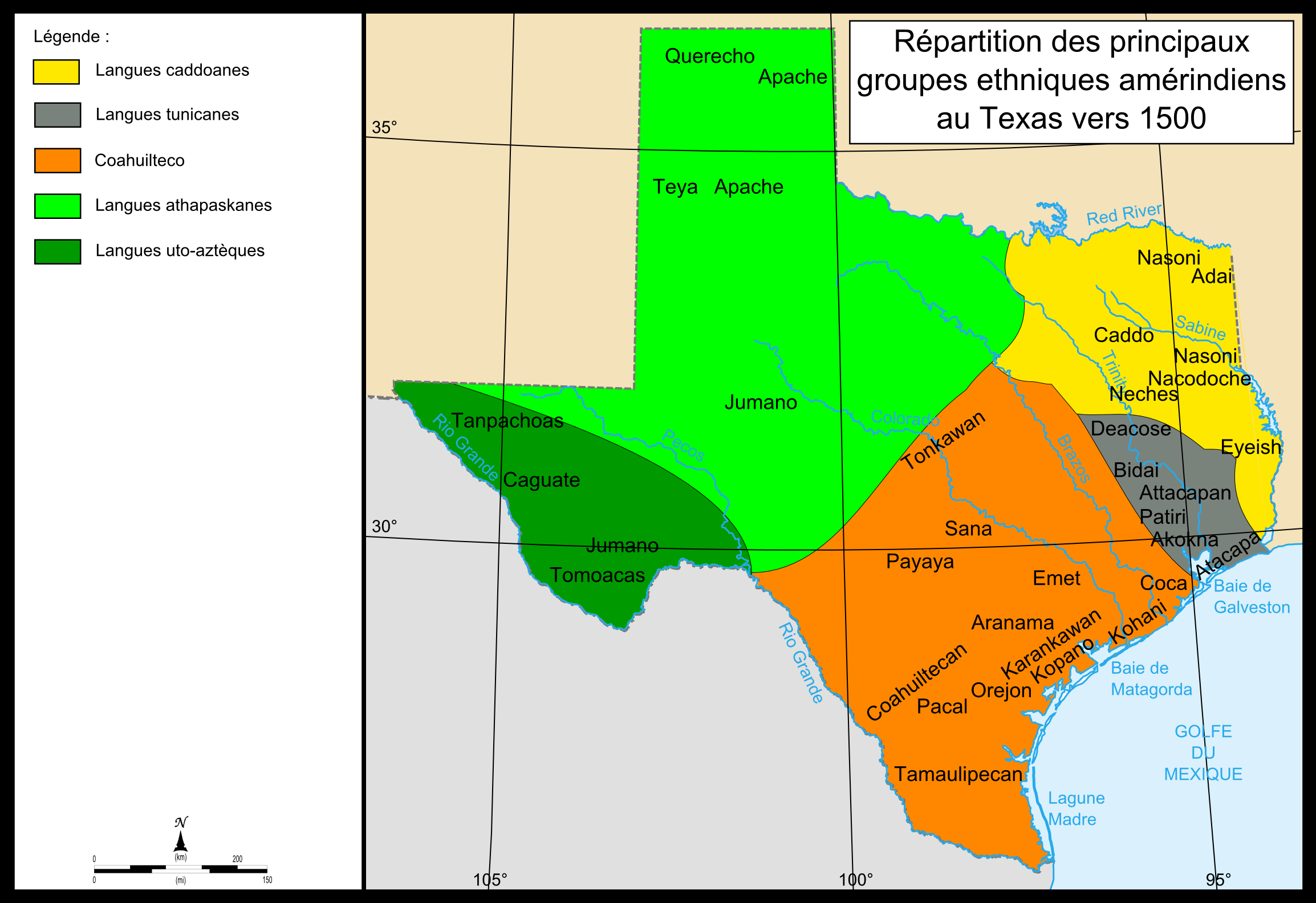

My

name is Felix Benavides, Orona Bonilla Salmeron and

a decedent of a Jumano Family. I am also on the

Jumano Indian Nation of Texas council member. I am

also the Family Historian. For many years my Jumano

family has been out of sight. My grandparents did not

mention much of our past, but I did get to talk to my

Great Grand Parents and understood the reason, which

is well documented by many authors.

My

name is Felix Benavides, Orona Bonilla Salmeron and

a decedent of a Jumano Family. I am also on the

Jumano Indian Nation of Texas council member. I am

also the Family Historian. For many years my Jumano

family has been out of sight. My grandparents did not

mention much of our past, but I did get to talk to my

Great Grand Parents and understood the reason, which

is well documented by many authors.

Sarah Schenirer was born in 1883 in Krakow, Poland, into a Chassidic

Jewish family. At that time, the expectation was that Jewish boys would

learn about their religion in special Jewish schools, and that Jewish

girls would attend publich schools and be instructed in Jewish thought

at home by their parents. This model may have worked in previous

generations, but Sara Schenirer saw firsthand how Jewish girls were

becoming woefully ignorant of Jewish topics and starting to assimilate.

She saw a crisis arising.

Sarah Schenirer was born in 1883 in Krakow, Poland, into a Chassidic

Jewish family. At that time, the expectation was that Jewish boys would

learn about their religion in special Jewish schools, and that Jewish

girls would attend publich schools and be instructed in Jewish thought

at home by their parents. This model may have worked in previous

generations, but Sara Schenirer saw firsthand how Jewish girls were

becoming woefully ignorant of Jewish topics and starting to assimilate.

She saw a crisis arising. Born into an assimilated Jewish family in Budapest in 1921, as a child

Hannah Senesh was drawn to Zionism and local Zionist youth group

activities. When she was 18 she made aliyah (moved to what would soon be

the state of Israel), settling in Kibbutz Sdot Yam, where she wrote

poetry and a play about kibbutz life.

Born into an assimilated Jewish family in Budapest in 1921, as a child

Hannah Senesh was drawn to Zionism and local Zionist youth group

activities. When she was 18 she made aliyah (moved to what would soon be

the state of Israel), settling in Kibbutz Sdot Yam, where she wrote

poetry and a play about kibbutz life.

No creo que hablen en broma. Son fanáticos y son capaces de cualquier

cosa.

No creo que hablen en broma. Son fanáticos y son capaces de cualquier

cosa.