|

Rapists, child molesters and pedophiles served in positions of trust

inside state-licensed addiction treatment centers because, in

California, no criminal background checks were required.

Addiction

counselors preached abstinence to clients even as they racked up fresh

drug and alcohol charges of their own; no system for reporting new

offenses existed.

State

regulators overseeing the rehab industry often failed to catch

life-threatening problems and, when they did, failed to follow up to

ensure that dangerous practices ceased.

These

blistering critiques of California’s weak regulation of addiction

treatment — delivered in a pair of reports from the Senate Office

of Oversight and Outcomes more than four years ago — indicted a system

that far too often produced deadly results for people at perhaps the

most vulnerable point in their lives.

Shortly

after the reports were written, the agency overseeing rehabs ceased to

exist, its responsibilities transferred to a different department. Hopes

ran high that California would modernize its approach to better protect

those who need help. Since then, some has changed for the better —

but much has changed for the worse:

• As

opioid addiction has soared, inexperienced and unscrupulous rehab

operators have rushed in to take advantage of mandatory mental health

treatment coverage required by the Affordable Care Act.

•

California’s notoriously hands-off approach to regulating the industry —

still predominantly non-medical even as other states push hard for a

more medical approach to care — makes it easy for almost anyone

to open a treatment center and bill insurance companies hundreds of

thousands of dollars per client.

•

California’s easy-enroll health insurance marketplace also has helped

cement the state as a go-to destination for addicts seeking to get clean —

or cash in — on what has become known as the Rehab Riviera.

•

Residential treatment facilities bring chaos to neighborhoods and swell

the homeless population with rehab rejects who are kicked to the curb

when their insurance runs dry.

•

Addicts trying to get clean — and their families — often

mistake California’s non-medical rehabs for facilities that provide

medical treatment, thanks in part to slick advertising. In non-medical

facilities, many are dying for want of proper medical care.

Since

the Southern California News Group’s investigation of the Rehab

Riviera began last winter, criminal probes of industry players have been

confirmed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and several local

district attorneys, including those in Orange and Riverside counties.

The California Department of Insurance is investigating irregularities

as well.

But

proposed laws aimed at closing loopholes in the regulatory system —

such as forbidding patient-brokering, the buying and selling of

well-insured addicts to the centers willing to pay the most for them —

have languished or died in the Legislature.

The

department charged with regulating the industry has advanced no

comprehensive plan to lawmakers to help correct problems that fester in

plain sight.

And as

lawmakers debate where rehab inspectors should be stationed, the

qualifications of drug counselors and how many rehabs should be allowed

per block (many are in ordinary tract houses in residential

neighborhoods) they don’t address the decidedly non-medical nature of

much addiction treatment in California.

“This

is a crisis and it’s growing,” said Mike Pearce, whose daughter,

Shannon, floated in and out of treatment centers until she was killed

Dec. 16 at the Santa Ana apartment she shared with another recovering

addict.

“The

governor should take the direct lead on this…It’s going to take

inspired leadership at the top. And we haven’t had inspired leadership

for a long, long time,” Pearce said.

“It

just galls me that they don’t care.”

Shannon

might still be alive if she had gotten some kind of care from the people

she turned to in faith, Pearce said. She seemed to be making progress

with one counselor, he said, until that counselor relapsed.

“Something

is seriously wrong with how we’re approaching this, and we’re not

confronting it,” said Walter Ling, professor of psychiatry and

founding director of the Integrated Substance Abuse Programs at UCLA.

“There is no leadership. We know it’s not working. We’ve known

that for years.”

Buck stops nowhere

While

governors in other states — Vermont’s Peter Shumlin, Ohio’s

John Kasich, Florida’s Rick Scott — have unveiled aggressive

plans to fight drug addiction and reform the treatment industry, Gov.

Jerry Brown has largely declined to engage.

When

the Southern California News Group summarized its findings for Brown —

including the deaths of at least a dozen people in non-medical detox

facilities, which are not allowed in several other states because of the

extreme health risks posed by withdrawal — the governor’s press

secretary, Ali Bay, said, “I don’t expect our office will have

additional information for you.”

The

department that Brown’s office referred us to for answers, the

Department of Health Care Services’ Substance Use Disorder Compliance

Division, is headed by Marlies Perez.

This

year, Perez’s department is rolling out a system to bring

medication-assisted treatment to California’s hard-hit northern

reaches. It also has hired more inspectors. But addressing the problems

outlined by the Southern California News Group’s probe are not her

department’s purview, she said.

“Our

authority is around the licensing of the facilities. Patient-brokering

is not within our jurisdictional authority. That’s the jurisdiction of

the Department of Insurance. And the state department that oversees

managed health care, that is not with the Department of Health Care,”

she said.

Nor is

it her department’s job, as the state’s regulatory experts, to bring

reform proposals to lawmakers. “We have the opportunity to weigh in on

bills and things brought forward, but the ultimate authority is going to

lie with the Legislature and the governor to make those decisions,”

Perez said.

Over

in the Legislature, several lawmakers are seeking reforms, without much

success.

A bill

that would forbid patient brokering was introduced by Sen. Steven

Bradford, D-Gardena, but stalled in committee over the summer. It has

been amended and awaits a new hearing.

Criminal

background checks are required for acupuncturists, dental hygienists,

optometrists and veterinarians, but substance abuse counselors can work

with vulnerable addicts for five years without officials probing their

background, noted a bill by Assemblyman Reggie Jones-Sawyer, D-Los

Angeles. His bill requiring such screening was overwhelmingly approved

by the Assembly, but stalled in the Senate.

A bill

by Sen. Tony Mendoza, D-Artesia, seeks to address over-concentration of

rehab centers by requiring at least 300 feet between new facilities –

a distance critics say should be at least twice that. A hearing is set

for that in January.

Sen.

Pat Bates, R-Laguna Niguel, sought a study examining whether sober

living group homes should be licensed if they provide counseling, manage

a resident’s schedule or do urine tests to ensure a drug-free

environment. That effort stalled, and her bill has been amended to ask

the Department of Health Care Services to figure out how to evaluate

neighborhood complaints about over-concentration; determine how many

rehab facilities are actually needed in the state; and figure out how to

track their outcomes.

Assemblywoman

Sharon Quirk-Silva’s bill placing a state complaint investigator

directly in Orange County — home to the highest concentration of

licensed rehabs in the state — faced stiff opposition. “The

system right now isn’t broken,” said Sherry Daley of the California

Consortium of Addiction Programs and Professionals at a public hearing.

Quirk-Silva’s bill has been amended, but no hearing has been scheduled

yet.

“You’re

right to feel as if the (issue) isn’t being resolved in a satisfactory

way,” said Quirk-Silva, D-Fullerton. “It’s frustrating.”

Part

of the problem is that too many people are profiting from the current

setup, she added.

“I

think there is some pushback from the addiction centers. They don’t

want to see these programs closed. They’re still making money.”

Treatment

in a non-medical facility can reap $3,410 per day, with monthly bills

topping $100,000 for some clients, according to documents filed in

court.

A

woman from Washington state ran up a $416,050 bill over several months

of treatment with San Clemente-based Sovereign Health.

Some

critics even suggest the basic model of the rehab industry isn’t

focused on wellness.

“There

is no money in sobriety,” said Dave Aronberg, state attorney for Palm

Beach County, Florida. “There is no incentive to recover in this

process. It will cost you your free housing, your free illegal gifts,

your friends. And now you have to move back home to live with Mom and

Dad and find a job.

“But

the insurance benefits will renew, and the cycle will start again if you

just test dirty. Because you can’t be denied coverage for a

pre-existing condition,” Aronberg added.

“Instead

of a recovery model, we have a relapse model.”

Community chaos

Much

addiction treatment in California happens in 6-bed homes in residential

communities.

Neighbors

of such facilities have, for years, complained about the chaos these

homes bring, but those complaints often are dismissed as NIMBY —

“not my backyard syndrome.” And because rehab homes are legally

protected under the Americans With Disabilities Act they don’t need

special permits to operate, leaving neighbors with little recourse.

Records

obtained by the Southern California News Group show that police and

emergency workers in Southern California routinely respond to complaints

connected to state-licensed, neighborhood rehabs. Calls come in for

rape, assault, suicide, attempted suicide, burglary, public

intoxication, child endangerment and indecent exposure, among others.

In

Pasadena, since 2012, police responded to 1,666 calls for service at

just 17 rehab addresses. Those included 91 mental health-related calls,

33 public intoxications, 16 sex offender registrations, 16 burglaries, a

dozen vehicle thefts, 11 batteries, four overdoses, two indecent

exposures, and one each of assault with a deadly weapon, lewd conduct,

prostitution, and child endangerment, according to call logs.

In the

eight south Orange County cities patrolled by the Orange County

Sheriff’s Department, there were 2,500 calls for service during that

same period. The heaviest-hit were San Clemente, where there were 926

calls, the majority to just six addresses; and San Juan Capistrano,

where there were 667 calls, the majority to just 10 addresses.

In the

city of Riverside, there were 1,052 calls for service at 26 licensed

rehab centers, including 186 mental health-related calls, 18 overdoses,

five sexual assaults, three rapes, one alleged child molestation and one

felon with tear gas. A single center on Brockton Avenue generated 285

calls for service.

“The

addicts in these facilities are not getting helped, they’re getting

hurt,” said Warren Hanselman of Advocates for Responsible Treatment, a

group pushing for better regulation in San Juan Capistrano.

Political will

Richard

Rawson spent years advising California on how to best regulate addiction

treatment as co-director of UCLA’s Integrated Substance Abuse

Programs.

“The

state drug and alcohol office never has been a particularly powerful

entity,” said Rawson, now retired. “I suspect that’s because

there’s not a lot of political support for getting out and cleaning up

this industry.”

It is

different in Rawson’s home state of Vermont. “Here you had Gov.

(Peter) Shumlin in 2014 doing his entire State of the State speech on

opioid addiction. It became the top priority in the state government.

That has never happened in California – there’s too much other stuff

going on.”

Perez,

head of the Substance Use Disorder Compliance Division, deserves credit

for channeling California’s entire $90 million federal grant toward

expanding medication-assisted treatment in hard-hit corners of the

state, Rawson said. But without leadership from the top, he added,

it’s hard to get more done.

“The

mess in the rehab industry is a problem that politicians seem to want to

avoid.”

Huntington

Beach filmmaker Greg Horvath produced a documentary, “The Bu$iness of

Recovery,” to expose what he calls the “gross deficiencies”

addiction treatment.

“The

industry must change,” said Horvath. “There must be oversight and

regulations in place that protect the public and the families who are

entrusting these centers with their loved ones. Treatment needs to be

more scientific and empirically validated. The educational requirements

for people treating addiction must be higher.”

UCLA

psychiatrist Ling agrees, suggesting much of the industry is built on

false claims: “This is a very critical point: There is a

misrepresentation of what they do because they make people believe they

are rendering medical services.”

Florida,

hard-hit by pill mills and deadly fraud in the treatment industry,

responded to this disconnect with new laws criminalizing dishonest

marketing, kickbacks and patient-brokering.

“We

shut these places down because the government had the courage to do

so,” said Aronberg, state attorney for Palm Beach County.

On

Wednesday, the state of New York launched a new ad campaign to alert

those seeking help about bogus rehab referral services. “Vulnerable

New Yorkers struggling with addiction are being targeted and falsely

promised life-saving treatment services and then are given inadequate

and ineffective treatment at outrageous costs,” Gov. Andrew Cuomo

said.

Fixing

California’s regulatory ills would require a significant overhaul of

the system, said Harry Nelson, founding partner of Nelson Hardiman, a

firm specializing in health care law. He’s not sure there’s an

appetite for it.

“The

problem is, drug rehab is complicated, so it doesn’t fit neatly into

the healthcare category or the community care framework,” Nelson said.

“It has been cut off from the rest of the health care system for so

long it has had a silo effect.”

Undoing

that isolation — by integrating addiction treatment into the

mainstream health care system — will ultimately address

irregularities, said Martin Y. Iguchi, a senior behavioral scientist at

the RAND Corporation and professor in the departments of Psychology and

International Health at Georgetown University.

“When

you have fraud like that, that’s because of the Wild West nature of

the programs that have popped up,” he said. “There hasn’t been a

lot of attention paid because, without funding flowing, nobody seemed to

really care. The more these programs are part of the traditional

(health) care system, the better off everyone will be.”

Said

Keith Humphreys, director for mental health policy at Stanford

University’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences:

“These problems are not common in oncology.”

Solutions

The

Southern California News Group has talked to hundreds of people about

how to address problems in rehab industry, and reviewed thousands of

pages of regulatory documents and academic studies. Some recommendations

from experts include:

•

Establish national accreditation standards for all addiction treatment

facilities and programs that reflect evidence-based care.

•

License addiction treatment facilities as health care providers.

•

Collect patient outcome data and make it available to the public.

•

Mount a national health campaign educating people about medical

responses to addiction and improve addiction treatment training in

medical schools.

•

Tighten up truth-in-advertising laws to rein in call centers that

intercept and broker patients to facilities that pay them.

•

Require more formal education, criminal background checks and state

licensing for addiction counselors and those who work in treatment

centers.

•

Expand the state’s power to license, regulate and shut down

facilities.

•

Tighten the special enrollment period for buying health insurance,

making it harder to do mid-year enrollments.

•

Forbid financially interested third-parties from paying health insurance

premiums, except for parents.

•

Just as Medicare rewards good hospitals for not having readmissions,

insurers can do same for addiction treatment providers. “Pay the good

ones more and the bad ones less,” said Florida state attorney Aronberg.

“It

is long past time for (the rehab industry) to catch up with the science.

Failure to do so is a violation of medical ethics, a cause of untold

human suffering and a profligate misuse of taxpayer dollars,”

concluded the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at

Columbia University.

Ling,

of UCLA, believes California can start small — by appointing a

commission to review how things are done, and how they might be done.

By Teri Sforza

| tsforza@scng.com, Tony Saavedra

| tsaavedra@scng.com and Scott Schwebke

| sschwebke@scng.com | Orange County Register

https://www.ocregister.com/2017/12/29/rehab-riviera-industry-struggling-to-get-clean/

|

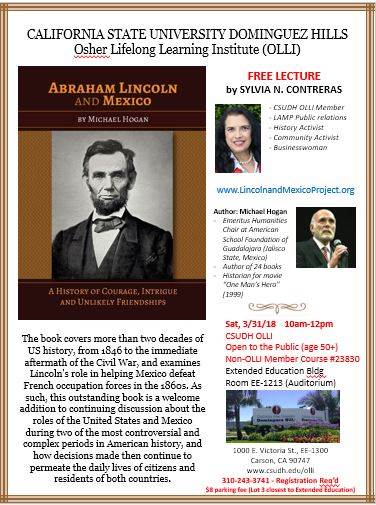

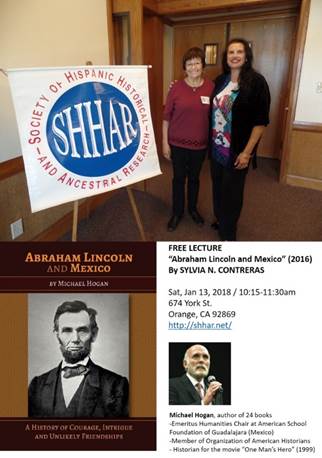

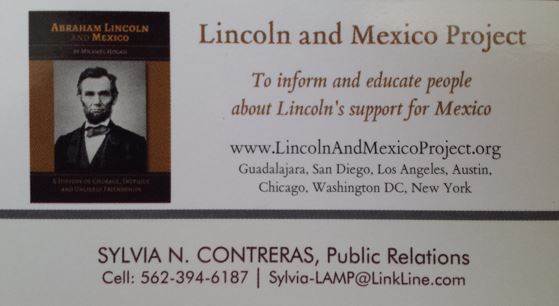

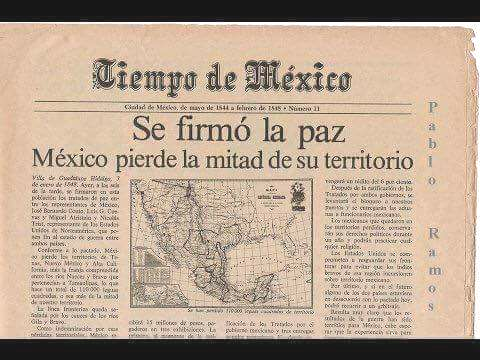

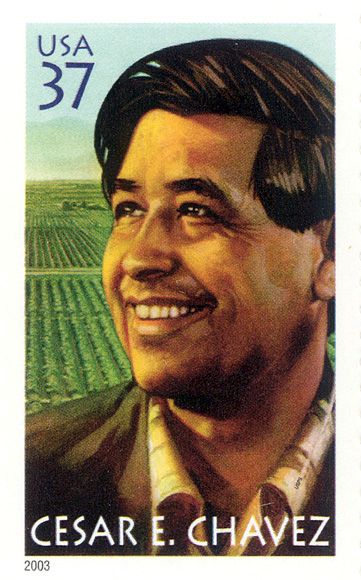

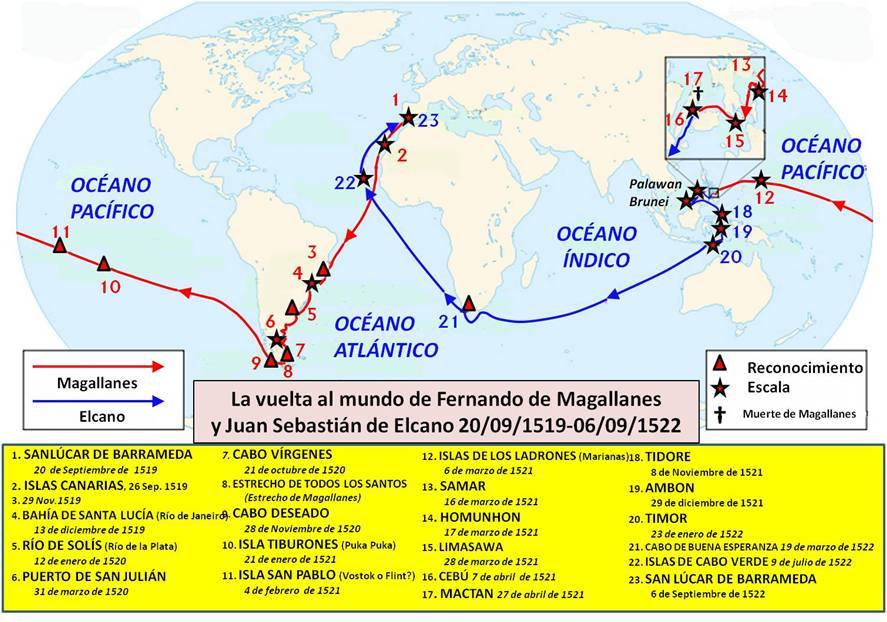

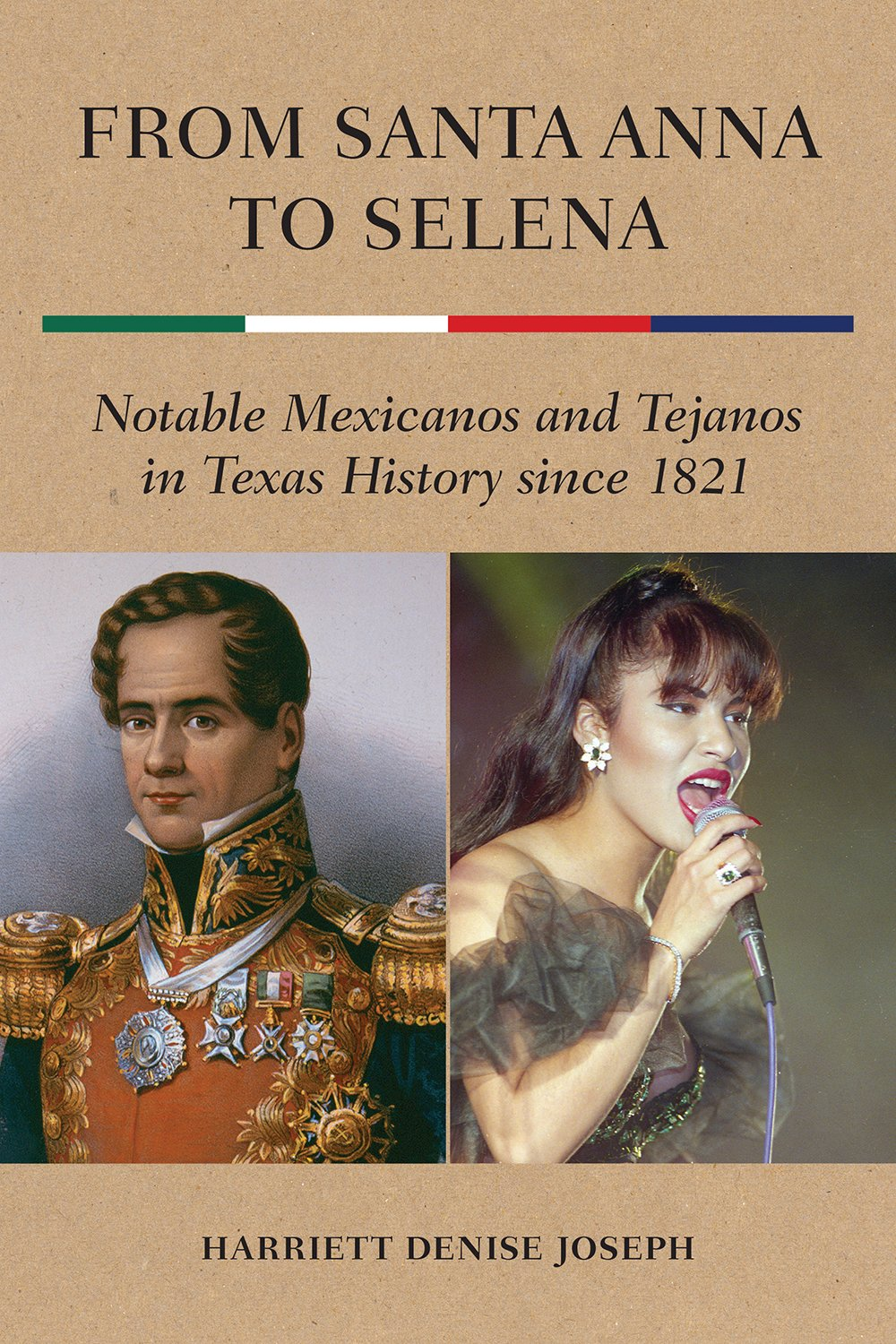

The

book inspired launching “Lincoln and Mexico Project” (LAMP) in

2016-17 reaching across the U.S.A. with representatives in

Guadalajara, Mexico; Los Angeles, CA; San Diego, CA; New York, New

York; Austin, Tx; and Chicago, IL. A few of LAMP’s goals are:

1) promote better relations between the U.S.A. and Mexico, 2)

integrate the book’s education into high schools and university

curricula, 3) bring the history “Abraham Lincoln and Mexico” to

the general audience. It seemed such an important movement, I

began volunteer efforts in Spring 2017. For additional

information, please visit: https://lincolnandmexicoproject.wordpress.com/about/

The

book inspired launching “Lincoln and Mexico Project” (LAMP) in

2016-17 reaching across the U.S.A. with representatives in

Guadalajara, Mexico; Los Angeles, CA; San Diego, CA; New York, New

York; Austin, Tx; and Chicago, IL. A few of LAMP’s goals are:

1) promote better relations between the U.S.A. and Mexico, 2)

integrate the book’s education into high schools and university

curricula, 3) bring the history “Abraham Lincoln and Mexico” to

the general audience. It seemed such an important movement, I

began volunteer efforts in Spring 2017. For additional

information, please visit: https://lincolnandmexicoproject.wordpress.com/about/

Now that you’re on our website, you have already

taken a step in the right direction. There are many things from

here that you can do. You can start by becoming a member. There

are two different types of membership, donor and sponsor. As a

donor member you will be supporting the development of the HDC,

‘Living History Museum’ Projects and of course, our horses.

Upon donation to any of these categories you will receive a letter

with explanations of what your donation has done for the

Now that you’re on our website, you have already

taken a step in the right direction. There are many things from

here that you can do. You can start by becoming a member. There

are two different types of membership, donor and sponsor. As a

donor member you will be supporting the development of the HDC,

‘Living History Museum’ Projects and of course, our horses.

Upon donation to any of these categories you will receive a letter

with explanations of what your donation has done for the

Dorothy

Lamour was one of the top movie

stars. Her genre was South

Pacific themes. Lamour

wore sarongs in 14 films.

Perfect timing. Dad always

resourceful was able to get some

walk on jobs as an extra for

mom.

Dorothy

Lamour was one of the top movie

stars. Her genre was South

Pacific themes. Lamour

wore sarongs in 14 films.

Perfect timing. Dad always

resourceful was able to get some

walk on jobs as an extra for

mom.  With

my sister in school, Dad brought

home a big rabbit, I think as

company for me. Scottie

enjoyed the new attraction

in the neighborhood.

Scottie would clear the low

fence easily and chase the bunny

all around the yard. They

would take a rest, nestled next

to each other, and then

start the race all over again.

They became good friends.

This is what I remember Bunny

looked like.

With

my sister in school, Dad brought

home a big rabbit, I think as

company for me. Scottie

enjoyed the new attraction

in the neighborhood.

Scottie would clear the low

fence easily and chase the bunny

all around the yard. They

would take a rest, nestled next

to each other, and then

start the race all over again.

They became good friends.

This is what I remember Bunny

looked like.

And,

every time Papá and I

went walking across the

river to Nuevo Laredo to

buy groceries or to get

a hair cut, he would

stop by the church to

say hello to Father

Lozano. The church

was just one block away

from the International

bridge. Father

Enrique Tomás Lozano

became well known in

Nuevo Laredo and Laredo

because he converted an

old building next to his

residence and made it

into a safe haven for

orphaned boys that he

called his beloved

"pelones."

He shaved their hair for

hygienic reasons.

He was very proud of

them. And, most

importantly, he sent

many of them to

Monterrey, Mexico, to

continue their

education, and some

became doctors,

engineers,

lawyers, and teachers.

And,

every time Papá and I

went walking across the

river to Nuevo Laredo to

buy groceries or to get

a hair cut, he would

stop by the church to

say hello to Father

Lozano. The church

was just one block away

from the International

bridge. Father

Enrique Tomás Lozano

became well known in

Nuevo Laredo and Laredo

because he converted an

old building next to his

residence and made it

into a safe haven for

orphaned boys that he

called his beloved

"pelones."

He shaved their hair for

hygienic reasons.

He was very proud of

them. And, most

importantly, he sent

many of them to

Monterrey, Mexico, to

continue their

education, and some

became doctors,

engineers,

lawyers, and teachers.