First published in Somos

en escrito

The

Latino Literary Online Magazine, November 15, 2017

Somos en

escrito caught up with the great Felipe

Ortego. This is his memoir about running in Luxembourg with an

Olympic gold medallist and learning about intention, winning, and

life. ~ Armando Rendon

|

|

|

Lamesch house on Rue de Beggen, Luxembourg, where the author

lived, in the 50s is nearby a bend in the street. The trolley, which he remembers,

vied with the bicycle and walking as transportation.

|

I met

Josef Bartel more than 60 years ago in the Luxembourg stadium one

evening towards the end of an August day in 1956 while running laps.

Luxembourg is a small country of some 1,600 square miles and, in those

days, had a population of less than a quarter million. Dismembered

three times in its history and governed at various times by France,

Spain, Austria, Germany, Holland, Belgium, Russia, and Italy, the

origins of Luxembourg date back to Roman times. One of the still

standing bridges of that era attests to the durability of Roman

architecture. In 1815 Luxembourg was made a grand duchy by the

Congress of Vienna and united with the kingdom of the Netherlands. Afterward

it became the crossroad of Europe.

From

anywhere in the capital city of Luxembourg one can see the rooftops

and watchtowers of the grand ducal palace rising from the center of

the city and from the American cemetery where General George Patton

lies buried. In 1945, Patton’s Fifth Armored Division liberated the

city from the Germans.

I

was new to Luxembourg, having arrived a scant week earlier, and at 30

still “working out.” I was progressing well with my form on the

track, I thought, though the clay track was a novelty for me. I had

started running as a kid in San Antonio and Chicago, mostly on asphalt

and concrete. When I went to the University of Pittsburgh, I learned

to run on a cork track. I managed the mile well enough to come in

third mostly and sometimes second in competition.

But

on that evening, in the Luxembourg stadium, I felt, rather than heard,

a runner behind me, moving so rhythmically down the straightaway I was

compelled to turn to see who could run like that. I learned later it

was Josef Bartel, whom I called Jose, 1500 meter gold medalist at

the1952 Helsinki Olympic Games and now an engineer with the city of

Luxembourg. As he slipped by me, I marveled at his form, so

effortless in motion. He nodded acknowledgement, and the second time

around dropped in beside me at my pace and introduced himself.

I told him I lived on the

Rue de Beggen in the Lamesch house, the horticulturalists renown-ed

for their roses. Yes, he knew the place well. He told me that during

the German occupation of Luxembourg a high German officer had lived

there.

I told him I lived on the

Rue de Beggen in the Lamesch house, the horticulturalists renown-ed

for their roses. Yes, he knew the place well. He told me that during

the German occupation of Luxembourg a high German officer had lived

there.

Yes,

I could understand that. It was an old, elegant 19th century manse

in the European style, built for a family of leisure. It sat on a

large acreage just north of the city on the way to Bitburg, Germany.

My family and I occupied only a section of the house, partitioned for

a part of the Lamesch family now gone. In one of those quaint Mozart

rooms on the upper storey of our section of the house I wrote and

pursued my interests in literature.

“What

brings you to Luxembourg?” Jose asked. I explained what brought me

to Luxembourg and how I came to be running in the stadium.

“I

could tell you were an American by the way you run,” he said. I

smiled, amused by that piece of deduction. “Americans are too wound

up when they run,” he said. “The only exception was Jesse

Owens,” he added. “But this is not the place to run,” he went

on. “This is the place to practice form, get a feel for the

relationship between you and the track.” Only the barest hint of an

accent suggested he was European and not American. Suddenly he spoke

to me in French. After a bit he said, “You speak French very well.

Almost like a native. Where did you learn it?

“I

studied it in college,” I said.

“You

certainly did not learn that kind of French in college,” he said,

emphasizing the word “college.”

“Well,

no,” I said. “I lived in Paris more than a year before coming

here.

“Of

course,” he said. “And where was college?”

“Pitt,”

I said. “The University of Pittsburgh.”

“And

your major?”

“Comparative

Studies. Philosophy, Languages, Literature, Writing.”

“I

see,” he said.

We

ran several laps in silence, then unexpectedly he began to speak

philosophically about running.

“You

see,” he started, “most people approach running through the mind.

Thinking a distance is something to be overcome by time. The clock becomes

the focus, not the run. Others are defeated by the distance. No sooner

are they out of the starting blocks than they are thinking about how

far they have to go or how much more they have to run.”

I

agreed with his premises. My own approach to running was to focus on

the next step, I explained.

“That

too can be a liability,” he said. “You forget about the field and

that the object of the run is to place first. Have you ever placed

first? He asked.

“No,”

I said. “Never!”

“Hm,”

he responded, and ran other laps without saying a word. Then he

apologized for hav-

ing

to leave me but he still had a fair amount of work to do on the track

before it got darker. He was preparing for a meet in Trier in Germany

that Saturday. Would I care to go?

I

accepted, and he went off, lapping me several times.

Before

leaving the stadium he called out. ”I’ll pick you up at your place

at 8 on Saturday morning. Okay?”

Saturday

morning he picked me up promptly at 8 a.m. in his black Citroen that

looked like something out of a Chicago gangster movie of the 1920s

or 30s. “It’s old and cheap,” he said. “Engineers don’t make

much money. And the gold on Olympic medals doesn’t bring very much

on the open market.

Saturday

morning he picked me up promptly at 8 a.m. in his black Citroen that

looked like something out of a Chicago gangster movie of the 1920s

or 30s. “It’s old and cheap,” he said. “Engineers don’t make

much money. And the gold on Olympic medals doesn’t bring very much

on the open market.

The trip to Trier didn’t take very

long. Trier is an old Roman city just north of where the Mosel River

joins the Saar in Germany. En route we talked about the United States,

Indo-China, our kids, our wives, our futures.

“So you’re a writer,” he said. “Written anything I’ve

read?” Tavern

in Trier.

“Not

yet,” I said, “But it’s coming.”

“What

do you write? Novels?”

“Nothing

that ambitious yet. Poetry, short stories, mostly journalistic

pieces. Reportage. I worked on the Pitt paper for three years and

interned with the Pittsburgh

Post Gazette the summer of 1952.

“Anything

published?”

“Yes,

but not by-lined. The New World Society of Pittsburgh published a

small chapbook of poetry by me four years ago.”

“I’d

like to read it sometime. What’s it called?”

“The

Wide Well of Hours.”

“How

are your children doing in school?” he asked, changing the subject.

“Fine,”

I said. “Just fine.”

“No

trouble with the languages?”

“None,”

I said. “They’re becoming multilingual.”

“That’s

good,” he said. “The more languages we learn the better off we

are. What language do you speak at home? With your wife and kids?”

“English

mostly. Some Spanish.”

“You’re

Spanish, aren’t you?” he asked. That’s a Spanish name you

have.”

“The

name is Spanish, but my folks were from Mexico.”

“But

you were born in the United States, weren’t you?”

“Yes,”

I said. “I’m an American.”

“But

you’re also Mexican?”

“Yes,”

I replied. Hyphenating my ancestry was still in the future. I thought

of myself as an American of Mexican ancestry. Achieving Chicano

consciousness still lay ahead of me.

“What

other languages do you speak–-besides English, Spanish and

French?”

“Some

Italian, a little Portuguese. I learned some Chinese when I was in

China.” I didn’t tell him I had studied Russian as part of my

tenure with the Air Force Survival School at Reno, Nevada. I was

cautious then about those revelations, especially about my work as a

Threat Analyst in Soviet Studies for the Air Force.

“Taiwan?”

he said, cutting into my thoughts.

“No,

China,” I said, “Mainland China.”

“Oh?”

he said, surprised. “When were you there?”

“Right

after the war,” I said.

“See

much?”

“Yes.

Shanghai, Peking, Tientsin, Tsingtao, and lots of poverty.”

“Poverty

is everywhere,” he said. Then after a pause, “Tsingtao? That’s a

port city in the Shantung Peninsula, isn’t it?”

I

was surprised that he knew that. “Yes,” I said. “I spent almost

a year there, after Shanghai.”

“Were

you in the Army?”

“No,

Marines.”

“I

was too young for military service,” he said. “I was ten when the

Germans occupied Luxembourg. After the war, I went to school in the

United States. But I missed Luxembourg, the Ardennes. I run there

every day. Maybe you’d like to join me?’

“Yes,”

I said.

The meet at Trier was exciting. Jose won the distance races handily.

He had come sure of himself, knowing he was going to win. “You

see,” he said on the way back to Luxembourg, “you have to see

yourself as the winner. Know you’re going to win.”

“And

if you don’t win?” I asked.

“That

can’t be,” he responded, matter of factly. “If you know you’re

going to win, there can be no other possibility.”

“None

whatever?”

“None.”

“Do

you always win?” I asked.

“Yes.

When my intention to win is high.”

“I

see,” I said, though still not quite sure of the meaning of his

words, trying to grasp the philosophy.

“When

my intention is not high, I don’t win. When your intention to win is

high, and you want to win, you will win.”

“Hm?”

I said.

“You

don’t believe that, do you?” he said, sensing my apprehension.

“How many wins have you had?”

“Wins?”

“Yes.

In running.”

“None,”

I said.

“Your

intentions are not very high then,” he said. “We’ll work on that

when we run in the forest.”

“Fine,”

I said, still perplexed.

“Don’t

worry about it,” he said. “It took me a while to get the hang of

it too.”

It

would take me almost two more decades to really get the hang of

it–the meaning of intention–not until my meeting with Werner

Earhart and EST (Earhart Seminar Training). In EST, “intention”

is the production of an outcome not predicated by the circumstances.

I didn’t understand that yet. It took years before I fully

understood the notion of intention. But I embraced the notion before

fully understanding it. I had achieved enough consciousness to

recognize verities and to direct them towards my own fulfillment.

The

Ardennes is an old forest between Luxembourg and Belgium, just east

of the Meuse River. Some of the fiercest fighting of World War One

took place there. In 1918 when the fighting stop-ped, the armistice

line ran practically through the Ardennes. Later I would find old

relics of the “great war” strewn everywhere I passed in the

forest. The kids found shells I cautioned them to throw away. In my

mind’s eye I saw the tragedy–and futility–of trench warfare.

The French with their impregnable Maginot Line. General Patton

called it a monument to man’s stupidity.

|

|

|

Hikers on a trail in the Ardennes Forest, near where the

author jogged with Josef Bartel

|

|

|

But

that was in another war. My own war was not much better. Our assaults

in the Pacific against fixed Japanese fortifications were suicidal.

The carnage. The incredible loss of human li-ves for small pieces of

land barely visible on maps. There was no glory in war; only

disillusionment–-a loss of innocence. That’s what made stories of

war so compelling, stories like All Quiet on the Western Front

and A Farewell to Arms. Not

the war itself, but the romantic aftermath of war. Everywhere about me

in the forest I sensed the consequences of war and its futility.

Thomas Gray had it right: The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

But

that was in another war. My own war was not much better. Our assaults

in the Pacific against fixed Japanese fortifications were suicidal.

The carnage. The incredible loss of human li-ves for small pieces of

land barely visible on maps. There was no glory in war; only

disillusionment–-a loss of innocence. That’s what made stories of

war so compelling, stories like All Quiet on the Western Front

and A Farewell to Arms. Not

the war itself, but the romantic aftermath of war. Everywhere about me

in the forest I sensed the consequences of war and its futility.

Thomas Gray had it right: The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

Jose

introduced me to the mysteries of the Ardennes and to the running

techniques he called “freifart”–free style.

“The

idea is to keep moving,” he explained. “Walking, jogging,

running. But never stopping. Americans train for running by

doing laps on a track. They try to psyche out the run by training in

the context of the meet. In Europe we train away from the

“track.”

After

warmups we started out with a brisk walk, then jogged several miles,

ran hard for two miles or so, walked briskly again, alternating the

sequence, always on the go. We made our way into the deep, sunless

sheol of the forest, bounding over layers of timeless leaves,

springing us forward like pogo sticks.

“Good

for balance,” Jose said.

Mile

after mile we ran, Jose instructing me on breathing, bringing air into

the lungs through nose and mouth.

“You

don’t need a lot of air,” he said, hardly puffing after the first

ten miles or so. “The body gets air through the skin. The lungs

don’t need a lot of air, just a steady flow to keep the brain going.

More importantly–don’t think about the air. The minute you do, you

start defeating yourself. That’s like a musician who starts to think

about the notes during a performance. The minute he does, he’s going

to make a mistake. A musician feels the music, let’s it all flow

rhythmically out of him. Same for a runner. You start thinking about

the run, the air, the distance, the time, you’re dead. Every run has

a rhythm of its own. Just like every piece of music. Different

tunes, different rhythms. When you start a run get a feel for its

rhythm. Relax, settle into the run. Concentrate on the form. Stretch

the legs, point the toes, get the tonus high, arms up, close to the

body, the way birds tuck their legs in when flying, minimum drag,

unnecessary motion.”

During

that first run in the forest I got a better sense of running. I had

never framed running in a philosophical context before. I just ran.

I learned good technique at Pitt, but no philosophy of running. That

seems strange coming from a student of comparative philosophy. But in

those days I was still learning about philosophy. I was still a year

away from my meeting with Jean Paul Sartre. A decade still lay ahead

of me and my epiphany as a Chicano.

Jose

and I ran in the Ardennes three times a week. At first I didn’t

think I had the stamina for it, but I discovered that while stamina is

certainly a product of conditioning it’s also a matter of mind.

It’s not our body that defeats us, but our mind, those mind-forged

manacles of William Blake, that small inner voice of the mind creating

unnecessary barriers and obstacles for us to overcome, telling us

we can’t do something, we can’t make it, we’re not strong

enough, not smart enough, encouraging us to fail.

Of

course, there are limits to endurance, but historically we learn

about men and women who surpass those limits of endurance. Helen

Keller had every reason to fail, but didn’t. Joan of Arc could

have failed, but didn’t. Later I would define that spark that takes

some human beings beyond the limits of endurance as “ignis–the

fire within.”

“That’s

right,” Jose said, smiling broadly when we talked about that fire

within. “You’ve read those stories about people who survive in

environments that should have killed them–-prisoners of war. It’s

not ‘heart’ that pulls them through. It’s a triumph of

‘spirit.’ I’ve known great athletes who had ‘heart’ but

lacked ‘spirit’–the will to go beyond what they experience as

pain. I don’t mean ‘spirit’ and ‘will’ are the same.

They’re not. ‘Spirit’ is ‘endurance.’ ‘Will’ is

‘determination.’ You see, people can endure captivity,

depredation, and countless other adversities. But if the determination

to endure isn’t there, then the spirit perishes, withers and dies,

oftentimes taking the body with it. You cannot just want to endure;

you must intend to endure. And that means doing all that’s necessary

to complete the intention.”

“I

understand,” I said. Years later I would understand more keenly

what Jose was talking about, more personally from the poem I Am,

Joaquin by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez, Chicano activist from

Denver. In the poem, Joaquin is the Chicano Everyman who must endure

for the sake of his people. From a philosophical commitment to endure,

he changes his stance assertively to an intentional commitment to

endure. From ‘I shall endure,’ he says ‘I will endure’.” The

utterance is without equivocation. At the end of the poem, Joaquin’s

intention to survive is clear and unequivocal. We know he’ll

survive. He has to survive–for his people.

For

me, however, at that moment the aperture of understanding what Jose

Bartel meant by the word “intention” had barely opened. But at

that moment I also realized how much of my life lacked intention, how

little I had committed myself to achieving a real triumph of the

spirit–-in running. I was nonetheless buoyed by that understanding,

however small its aperture.

The

weeks passed quickly. At 30, I was in the best physical shape I had

ever been. More importantly, though, I was mentally at one with my

body. I ran easier alongside Jose. In the Luxembourg stadium he

taught me how to “feel” the track, how to improve my form on the

turns, how to maximize the straightaways. At times I’d catch him

smiling, nodding, knowing I was grasping a philosophy of life that

included running. That’s what it was: a philosophy of life, not a

philosophy of running. Running was just a manifestation of that

philosophy. Running was not the object; life was. I remembered a

doggerel dictum of my youth: “As you wander on through life,

whatever be your goal; keep your eyes upon the donut, and not upon

the hole.” I was to discover there was more philosophy in that

doggerel than perceived.

That

October I entered the lists for the American All France Track &

Field Competition in Chaumont, the capital city of Haute Marne in

Northwest France. My family came to cheer me on. Jose said he came to

see me win.

“You

do want to win this race?” he asked, warming up with me in the

minutes before the mile run.

“Yes,”

I said. “I do.”

“Doesn’t

sound like it,” he said. “Look! Close your eyes! Visualize the

track. That’s it. Take three mental laps around the track. As you

make that first turn, start stretching your stride. Don’t fight the

track. Don’t change your rhythm. That’s it! You’ve got it! Move

on past the leader. Keep your eyes on the tape. You’re going to be

number one. Hear? Number one! Did that feel good?” he said, as I

opened my eyes.

“Yes,”

I said. “That felt good.”

“Make

it happen, just the way you saw it,” he said.

“I

will! I will!” I said, surprised by the strength of conviction in my

voice. Many people comment today about the strength of conviction in

my voice. I tell them it’s my Marine Corps voice, but I know it’s

the voice Jose Bartel helped me find.

S

S

To contact Louis J. Benavides

To contact Louis J. Benavides

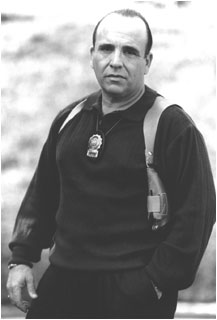

Retired

Colonel, United States Air Force Reserves, Samuel Idrogo, was

born in Laredo, Texas on February 15, 1935. He was born to a

family from humble beginnings with three sisters and one

brother. As a young child, Colonel Idrogo was always known to

spend a lot of time with model airplanes. He attended Laredo

Martin High school and had a strong interest in mathematics

and science courses. He was a distant runner on the track team

and was selected as ROTC Cadet of the Year and voted “Best

All-Around Male.” In his senior year, Colonel Idrogo served

as Class President. He was selected as the Executive Officer

of the Junior ROTC as well as President of the Pan American

Student Forum. He was one of two seniors selected to attend

Texas Boys State for outstanding students. He also became

President and co-founder of the Laredo Junior LULAC (The

League of United Latin American Citizenship) from 1953-1954.

Colonel Idrogo graduated high school in 1953 in the top 5% of

his class. In his high school yearbook, he was selected to be,

“One Most Likely to Succeed.”

Retired

Colonel, United States Air Force Reserves, Samuel Idrogo, was

born in Laredo, Texas on February 15, 1935. He was born to a

family from humble beginnings with three sisters and one

brother. As a young child, Colonel Idrogo was always known to

spend a lot of time with model airplanes. He attended Laredo

Martin High school and had a strong interest in mathematics

and science courses. He was a distant runner on the track team

and was selected as ROTC Cadet of the Year and voted “Best

All-Around Male.” In his senior year, Colonel Idrogo served

as Class President. He was selected as the Executive Officer

of the Junior ROTC as well as President of the Pan American

Student Forum. He was one of two seniors selected to attend

Texas Boys State for outstanding students. He also became

President and co-founder of the Laredo Junior LULAC (The

League of United Latin American Citizenship) from 1953-1954.

Colonel Idrogo graduated high school in 1953 in the top 5% of

his class. In his high school yearbook, he was selected to be,

“One Most Likely to Succeed.”

J

J

e

e

The

dealer hesitated for what seemed a lifetime then said, "You gotta

be real" and uncocked the .45.

The

dealer hesitated for what seemed a lifetime then said, "You gotta

be real" and uncocked the .45.

Pausing

over lunch, Patrick Charpenel, the new executive director of

Pausing

over lunch, Patrick Charpenel, the new executive director of

El

pasado 21 de noviembre, se llevó a cabo el tendido de dibujos para

seleccionar las obras ganadores del Vigésimo Primer Concurso de Dibujo

Infantil "Éste es mi México" 2017, cuyo tema fue “La

Mariposa Monarca y su Ciclo de Vida en Norteamérica”, en las

instalaciones de la Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Ciudad de México.

El

pasado 21 de noviembre, se llevó a cabo el tendido de dibujos para

seleccionar las obras ganadores del Vigésimo Primer Concurso de Dibujo

Infantil "Éste es mi México" 2017, cuyo tema fue “La

Mariposa Monarca y su Ciclo de Vida en Norteamérica”, en las

instalaciones de la Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Ciudad de México.