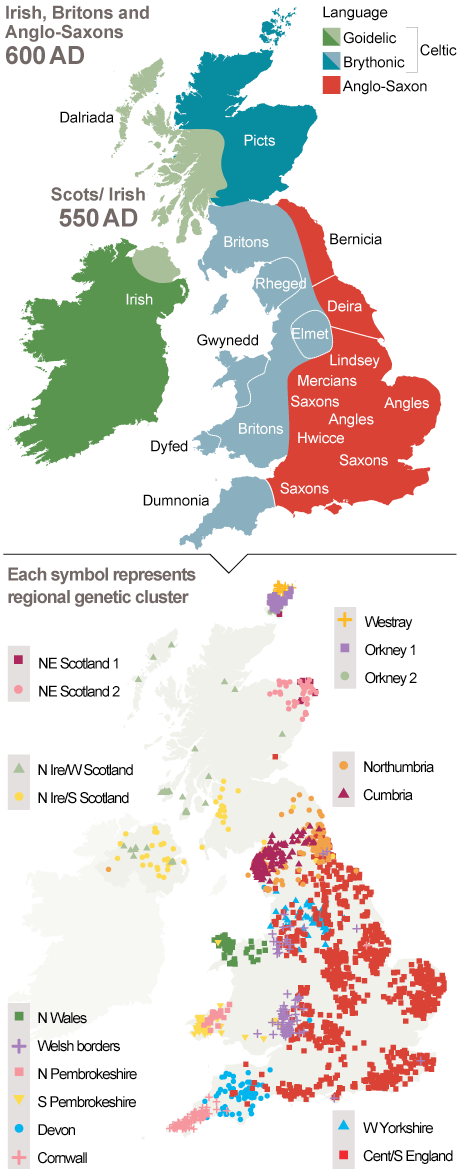

|

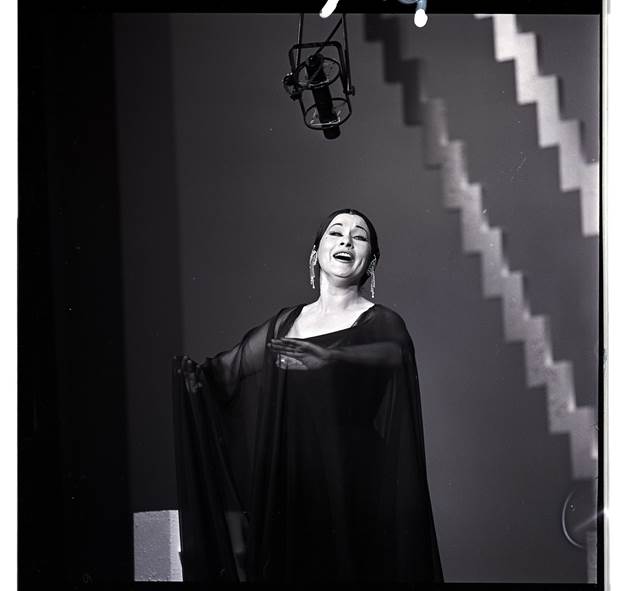

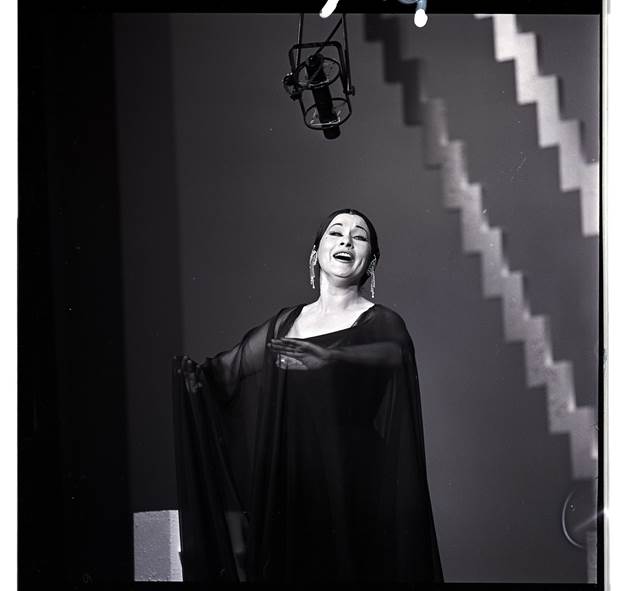

Yma Sumac poses for a portrait seen on the cover of her legendary 1950

album, "Voice of the Yxtabay." (Michael Ochs Archives /

Getty Images)

As a Peruvian kid growing up in Southern California, Id pick

through my fathers record collection, between the LPs of Peruvian

creole waltzes and Mexican ballads, to admire a strange album by an

alluring woman dripping in jewelry, posing before an erupting volcano.

The album was Voice of the Xtabay. And the woman was Yma

Sumac, the Peruvian songstress with the four-octave voice that

launched the musical genre known as exotica, a cinematic fusion of

international styles that allowed mid-20th century audiences a taste

of the mysterious and the remote.

Sumac was the imperious, raven-haired Inca princess

descendant of the last of the Incan kings, according to lore

who maintained an extensive wardrobe stocked with sumptuous gowns, her

crimson lipstick always applied to perfection. It was this Peruvian

girls ultimate fantasy.

Peruvian singer Yma Sumac in indigenous-style regalia in 1952. (AFP/Getty

Images)

It was also a piece of fiction. Yma Sumac may have been from

Peru. But her exotic Peruvian persona was invented in Los Angeles.

Hollywood took this nice girl who wanted to be a folk singer,

dressed her up and said she was a princess, says her biographer,

Nicholas E. Limansky, author of Yma Sumac: The Art Behind the

Legend.

And she acted like it.

Voice of the Xtabay, the 1950 album that introduced her to

global audiences, seemed like otherworldly evidence of her power.

It opens with the smash of a gong, ringing in Taita Inty, a

song described as a traditional Incan hymn that dates back to 1000

B.C. (Never mind that the Inca civilization didnt get rolling

until more than 2,000 years later.) It segues to tunes like Tumpa,

full of guttural scatting that evokes a wah-wah trumpet. All of it is

held together by Sumacs operatic trills, which could leap from low

growls to high-C coloratura that sounded as if it could shatter glass.

She took Peruvian traditional music, set it in the popular

music vein and sang it with the voice of a coloratura soprano but

infused it with jazz and blues, says Limansky. Its a

fascinating concoction.

With composer Les Baxter setting Sumacs Andean stylings and

symphonic interludes against groovier beats, Xtabay bore no

resemblance to any Peruvian music I grew up with or have heard on any

trip to Peru. (Gongs, for one, are from Asia, not the Andes.) The

album sounds more like a soundtrack for a 50s-era jungle epic,

featuring melodies that beg for a rum drink in a ceramic Polynesian

tumbler. It was irresistible.

Sumac was known for her glamorous, queenly outfits seen here in

1957. (Estate of Yma Sumac / Damon Devine)

Added to this were the machinations of the overheated publicity

department at Hollywoods Capitol Records, which fabricated all

manner of legends about Sumac, the supposed Inca blue-blood, crooner

of mysterious Andean hymns, as a way of drawing the publics

attention.

Among them: that the albums title song, Xtabay, was

about the legend of a young Incan virgin who had a forbidden

love with a high prince of an Aztec kingdom. No such legend

exists.

Audiences, however, ate it up. So did I. To me, Sumac was a rare

representation of the Andean in U.S. popular culture (albeit one

distorted by the funhouse mirror that is the entertainment industry).

And it was a representation soaked in glamour.

Sumacs boom years were in the 50s and 60s, but thanks in

part to Capitols epic myth-making, she had a surprisingly long

career. performing into the 1990s, when she was well into her 70s.

Her first significant appearance, at the Hollywood Bowl in August

1950, was received with astonishment followed by rapturous applause.

From there flowed numerous albums including my favorite,

Mambo! from 1954 as well as performances all over the U.S.

and Europe. In 1960, she undertook a historic 40-city tour of what was

then the Soviet Union that lasted for months.

Cult following

Over the course of her life, Sumac appeared on television talk

shows from Steve Allen to David Letterman. Her music has appeared in

commercials and on numerous Hollywood soundtracks, including The

Big Lebowski and Mad Men. And its been sampled by hip-hop

musicians. The Black Eyed Peas employed the groovy opening from Bo

Mambo in their 2003 single Hands Up.

Today, eight years after her death at age 86, Sumac remains the

subject of fan sites, Pinterest pages and Facebook groups. Shes

inspired a veritable rabbit hole of lip-sync videos on YouTube. (One

by Argentine actor Luciano Rosso, looking piratical, is particularly

delirious.) Last fall, she received the ultimate digital nod when she

was featured as the Google Doodle on the 94th anniversary of her

birth.

Sumac could have easily gone down in the history books as a

musical footnote. And if shed remained a run-of-the-mill folk

singer, she probably would have. But the combination of her beauty,

her unusual music and the colorful stories that surrounded her

transformed her into a legend with a devoted cult following. (I was

once chastised on social media by a fan for not being sufficiently

reverent.)

The high camp didnt hurt either the feathered headdresses

and eyeliner on fleek not to mention her stage design, with

Styrofoam volcanoes and totems. A Times review of a 1955 concert at

the Shrine Auditorium notes her phenomenal voice as well as a

touch of the ridiculous, namely a set studded with pillars of

fire.

Sumac performing in 1952 an image from her personal archive.

(Estate of Yma Sumac / Damon Devine)

She was unique in the combination of things that she

embodied, says Peruvian anthropologist Zoila Mendoza, chair of UC

Davis Native American studies department and daughter of a woman

who was close friends with Sumac as a teen. It was a whole

fantasy.

Sumac was born Zoila Augusta Emperatriz Chavarri del Castillo in

Perus Cajamarca region of the northern Andes on Sept. 13, 1922.

(She later took the stage name Imma Summack, her mothers name,

which morphed into Yma Sumac after her move to the U.S.)

She was not, as one Parisian publication once wrote, raised in a

miserable hut of dried earth. In fact, her well-to-do family

included a physician and a judge. Her father was involved in local

civic affairs; her mother was a school teacher.

Definitely she was elite in the area, says Mendoza, whos

studied indigenous performance in the Andes and written about Sumac.

As a teen, Sumac moved to Lima to go to school. It was there in

Perus capital that she met Moisés Vivanco, a noted folk musician

who would shape her early career and whom she would ultimately

marry and divorce (twice). One popular Sumac legend, crafted by the

fabulists at Capitol Records, has Vivanco traveling for days to a

remote mountain region to seek out the singer known for

talking with the birds, the beasts, the winds.

Not quite. Vivanco met Sumac at a rehearsal in Lima, where, after

hearing her sing, he invited her to participate in a folkloric event.

L.A. is full of people

like her. People like Angelyne these self-invented people.

Joy Silverman,

former director of LACE

Sumac's personal travails often made headlines: Such as the family

spat captured by a Times photographer in the 1950s. (Los Angeles

Times)

All of this raises the issue of Sumacs supposed Inca lineage.

Her mothers surname, Atahualpa, was that of the last Inca emperor.

Whether that made Sumac a real-deal royal (or someone who could even

claim indigenous identity) is unknown.

She likely spoke some Quechua, one of the principal indigenous

languages of the Andes, as did most people who then lived in the

highlands. But she was a fair-skinned mestiza, a mix of Spanish and

Indian. She was white compared to most Andean people, Mendoza

notes. She had green eyes. She and my mother were very close

friends. My mom also has green eyes. So they were these two pretty

Andean women with green eyes.

But Sumac emerged at a time when Peru was paying more attention

to its indigenous roots. The wide dissemination of the archaeological

wonders at Machu Picchu after 1911 brought attention to the

countrys resplendent Inca past.

In that context, the whole institution of folklore emerged,

says Mendoza, referring to the burgeoning industry built around Andean

indigenous music. Recordings were made, radio programs launched and

festivals held.

Sumacs early repertoire reflected this musical current,

including, for example, huaynos, brisk Andean highland ballads

featuring strings and flute. (Some of these are in the 2013

compilation album by Blue Orchid Records: Early Yma Sumac: The Imma

Summack Sessions.)

By the time Yma Sumac came about, there was a whole

infrastructure that allowed her to become a national figure,

Mendoza explains. Before that, it wouldnt have happened.

Incas in the deli

Sumac and Vivanco became well known in Peru and had successful

engagements in the important Latin American media centers of Argentina

and Mexico. A successful recital at Mexico Citys prestigious

Palacio de Bellas Artes came at the invitation of Mexicos

president. In 1946, the pair moved to New York City, figuring that

their success in Latin America boded well for the U.S. market.

But American audiences werent exactly rushing out to see

Andean folk music. Sumacs early years in New York, as part of a

group called the Inca Taqui Trio, were spartan. They played supper

clubs, Borscht Belt resorts, business conventions and, for a time, a

delicatessen in New Yorks Greenwich Village, where a magazine

writer for Colliers would later write that Sumac could be found

performing in a back room richly blanketed with the aroma of

pickled herring, salami and liverwurst.

Hollywood took this nice

girl who wanted to be a folk singer, dressed her up and said she was a

princess. And she acted like it.

Nicholas E.

Limansky, biographer of Yma Sumac

Yma Sumac performing in 1964. (ABC Photo Archives / Getty Images)

The trio nonetheless developed a following. One local television

appearance sparked the interest of a talent agent who helped Sumac

land a deal at Capitol. The Inca Taqui Trio was too folkloric for the

label, so the label instead built an album around Sumacs voice.

Enter: Exotica master Baxter, and a post-World War II U.S. public

ready to be seduced by fantasy.

Also, enter: Los Angeles.

The record deal necessitated a move to Southern California, and

by the late 1940s the couple were comfortably ensconced in tony

Cheviot Hills on L.A.s Westside. The move was key in Sumacs

metamorphosis from talented folk singer to Inca exotica pioneer.

I dont know if this could have happened in another city,

says Limanksy. New York has Carnegie Hall and the Metropolitan

Opera ... famous classical institutions, and things were geared around

that. But in Los Angeles, you had the film industry and everything

that entailed. Her whole transformation, it does smack of Hollywood.

... It was very cinematic.

The tarted-up Inca princess identity was not something that Sumac

was initially wild about. She wanted to be a folk performer,

says Limansky. She really didnt like it at all.

But once Sumac re-invented herself, forced like many performers

to create a new sound in the name of success, she embraced the role

with haughty grandeur. Known for striding on stage as if shed

arrived to reclaim her empire, she demanded the undivided attention of

her public. In later years, shed storm off if spectators so much as

opened their mouths.

She looked like a princess and she acted like one, says

Limansky, who attended some of her New York shows in the 80s.

She was entertaining, but not in a let me get in your face and

laugh with you kind of way.

She was very formal with the

audience.

This regal quality translated to her roles in Hollywood films.

In 1954, she appeared in the Charlton Heston adventure flick

Secret of the Incas as Quechua maiden Kori-Tika. In it, Sumac

gives a pair of surreal mountain-top performances at Machu Picchu. She

also throws serious side eye at Hestons European love interest,

played by Nicole Maurey. When Maurey tells her, You speak English

very well, Kori-Tika replies cattily, So do you.

Its a very different depiction from that other mid-century

South American icon, Carmen Miranda, the Brazilian bombshell,

seen as the flirty Latin party girl in the towering fruit hat. Sumac

was way too royal for that.

Interestingly, Sumacs noble persona (a role some say she came

to believe) was built around ideas of Inca culture that had blossomed

during Perus indigenist period ideas that werent always rooted

in fact.

When she became a folkloric artist in the 30s, there had

been a couple of decades in Peru of composers and musicians who had

been creating symphonies and these really sophisticated pieces of

music based on an invented idea of what the Inca sound was like,

says Mendoza. It had very little to do with what contemporary

indigenous people were actually playing.

Sumac was channeling a concocted notion of Inca identity as an

invented Inca princess. A fiction born in Peru adds another layer of

fiction in Hollywood, and from that fiction rises Yma Sumac. What

could be more Los Angeles?

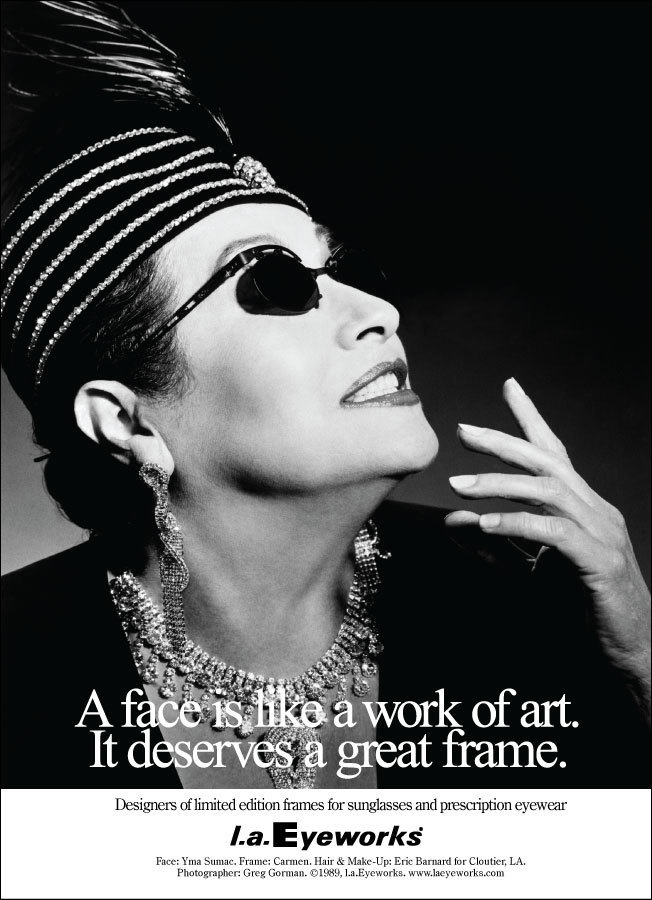

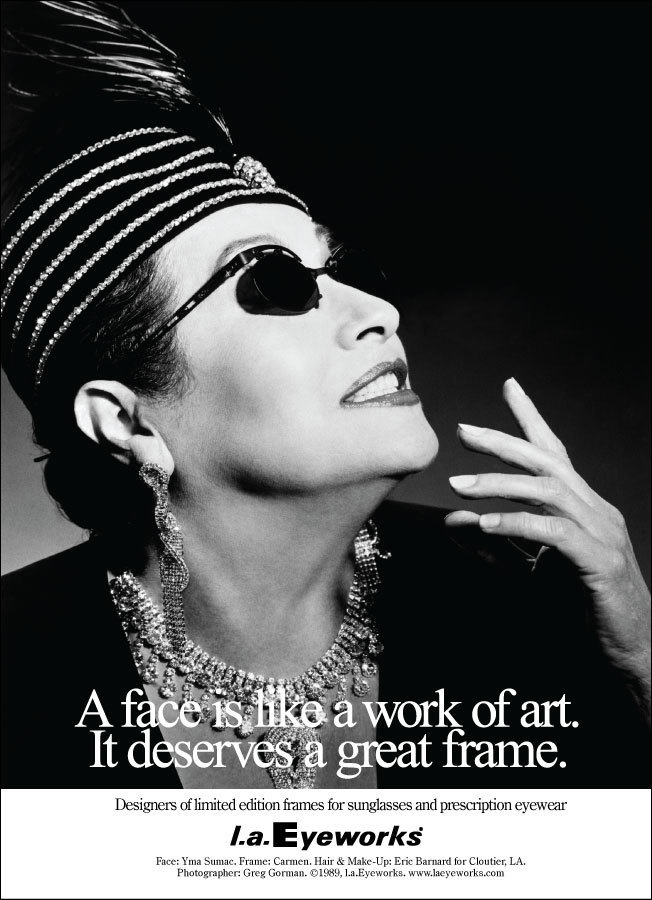

Yma Sumac's ad for l.a.Eyeworks in the 1980s. (Greg Gorman for

l.a.Eyeworks)

L.A. is full of people like her, says Joy Silverman,

director of Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions through most of the

80s. People like Angelyne these self-invented people.

In the late 1980s, Silverman asked Sumac to perform at a LACE

fundraiser when the organization was located in downtown L.A., a

pioneer in what is now the thriving Arts District.

She was exactly what you would imagine, Silverman says.

You were in the presence of this dramatic Peruvian songbird. She

was never out of character.

Around the same time, Sumac also appeared in sleek shades and

plumed hat in one of l.a.Eyeworks iconic magazine ads, part of

a campaign that featured entertainers such as Grace Jones and Iggy

Pop.

It was Yma Sumac we had to do it! says

l.a.Eyeworks co-founder Gai Gherardi, who recalls a petite woman of

monarchical bearing with a taste for bananas. Her image, she knew

what it looked like, and she lived up to it.

In her late years, Sumac played regular cabaret engagements at

the now-defunct Cinegrill and the Vine St. Bar & Grill jazz club,

not far from her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. (Shes the only

Peruvian with that honor.) Her cabaret shows brought out a crowd that

author Tom Lang, who worked at Vine St. in the 80s, describes as

Sunset Boulevard on ayahuasca.

The pre-show atmosphere was anticipatory, a legend returns,

he says via e-mail from Bali, where he now lives. Opening night,

sold out. A group of tiny Peruvians, impeccably dressed, at one table.

[Pianist and author] Leonard Feather in his regular booth (throne).

Bill Murray and his entourage, up front.

Sumac was an uneven performer in those years with good

nights, as well as terrible ones, her voice cracking, her temper foul.

The show at Vine St. was one of the latter. I wanted to take her

off the stage and hug her and tell everyone else to leave her

alone, recalls Lang.

Yma Sumac in the '80s, when she made occasional appearances at clubs.

(Los Angeles Times)

There are other L.A. stories, too. About her taste for El Pollo

Loco and her shopping trips to Bullocks Wilshire. She must have had

300 pairs of vintage shoes from throughout the 50s, recalls her

friend and former assistant Damon Devine, who runs the tribute website

yma-sumac.com.

The singer, who was sold to American audiences as a wonder from a

strange land, was, in the end, just another grand dame living on the

Westside (she later moved to West Hollywood), who might enjoy an

afternoon of listening to Eurodance with her assistant.

Ultimately, it was in L.A., the city that made her who she was,

that Yma Sumac would ultimately come to rest.

Not long ago, on a warm afternoon, I paid a visit to Sumacs

grave at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. Its in the same mausoleum as

Iron Eyes Cody, a second-generation Italian American performer also

known for a manufactured indigenous identity. (He frequently played a

Native American in the movies and told the press he was Cree and

Cherokee.) In another part of the building lies Constance Talmadge,

the silent-screen star.

My father used to roll his eyes at Sumacs claims of Inca

nobility. But Los Angeles, a mestizo city and land of the faux

historic, requires a ruler. Why not Sumac? In the photo displayed on

her tomb, she is perfectly made up, wearing an indigenous textile and

earrings as big as chandeliers. Just like an Inca queen.

Editor Mimi: I particularly loved

sharing this article. My step-dad, Elias "Al"

Schwartz was a musician,

violinist with the Pasadena Civic Symphony Orchestra, and owner of a radio

station, the Better Music Station. In the early 1950s, Latin American music was very popular, especially with big

bands. My step-dad raved over Yma Sumac's musical

range, from the very deepest and lowest sounds to the highest .

. . all crystal clear. He was enthralled. I have very fond memories sitting and

listening to her amazing voice with Al, enjoying his appreciation of

her unique talent.

Sent by Sister Mary Sevilla

|

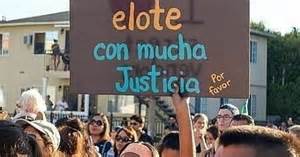

SACRAMENTO,

CALIF., (Aug. 15, 2017) - Benjamin Ramirez, most

recently known as "El Elotero" - the street

vendor who in mid-July defended his business on a Hollywood street

corner from racist and violent behavior - will personally deliver

his message for small business owners participating in the annual

convention of the California Hispanic Chamber of Commerce this month

in Sonoma County. "No hay que quedarnos callados. Hay que

defender nuestros derechos de vendedores ambulantes,"/"We

should not remain quiet. We should defend our rights as street

vendors," said Ramirez.

SACRAMENTO,

CALIF., (Aug. 15, 2017) - Benjamin Ramirez, most

recently known as "El Elotero" - the street

vendor who in mid-July defended his business on a Hollywood street

corner from racist and violent behavior - will personally deliver

his message for small business owners participating in the annual

convention of the California Hispanic Chamber of Commerce this month

in Sonoma County. "No hay que quedarnos callados. Hay que

defender nuestros derechos de vendedores ambulantes,"/"We

should not remain quiet. We should defend our rights as street

vendors," said Ramirez.

*

*

Gabriela Mafia ME 00, EdD 02 has been superintendent of Garden Grove Unified since 2013. Photo courtesy of Garden Grove Unified School District.

Gabriela Mafia ME 00, EdD 02 has been superintendent of Garden Grove Unified since 2013. Photo courtesy of Garden Grove Unified School District. Michelle King EdD 17 became superintendent last year at LA Unified. Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Unified School District.

Michelle King EdD 17 became superintendent last year at LA Unified. Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Unified School District.

The recent July issue of Somos Primos includes an article describing

the activities of Yturralde's Hispanic Heritage Project in Mexico.

The recent July issue of Somos Primos includes an article describing

the activities of Yturralde's Hispanic Heritage Project in Mexico.

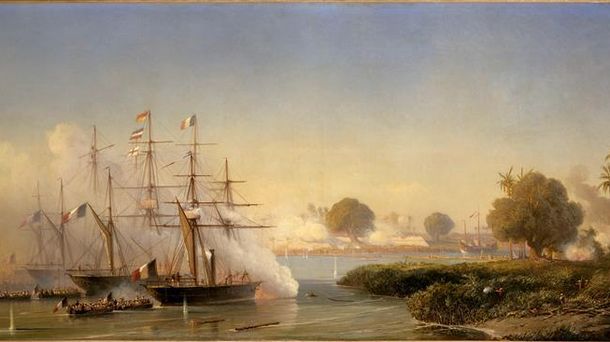

The Battleship Maine

The Battleship Maine

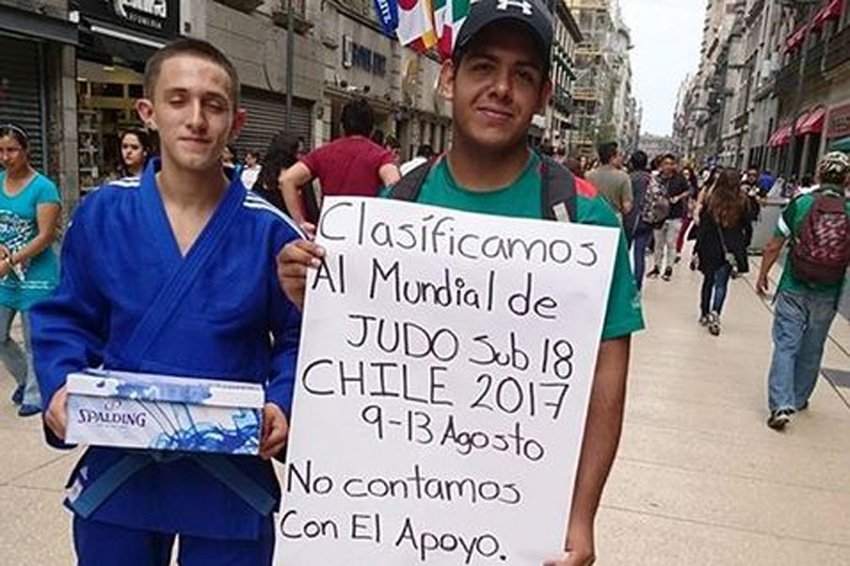

Nor is he the only one this week. Another junior athlete in a similar situation is gymnast Kimberly Salazar.

The 13-year-old originally from Xalapa, Veracruz, but now resident in Mexico City, won four medals at the recent national Youth Olympics in Monterrey, Nuevo León. That performance qualified her for the Pan American Rhythmic Gymnastics Championships that will be held in October in Daytona Beach, Florida.

Nor is he the only one this week. Another junior athlete in a similar situation is gymnast Kimberly Salazar.

The 13-year-old originally from Xalapa, Veracruz, but now resident in Mexico City, won four medals at the recent national Youth Olympics in Monterrey, Nuevo León. That performance qualified her for the Pan American Rhythmic Gymnastics Championships that will be held in October in Daytona Beach, Florida.

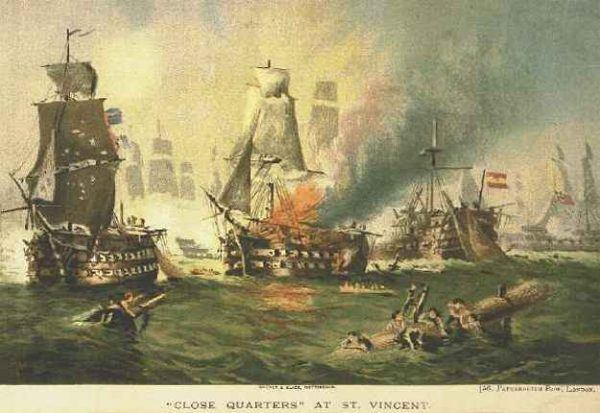

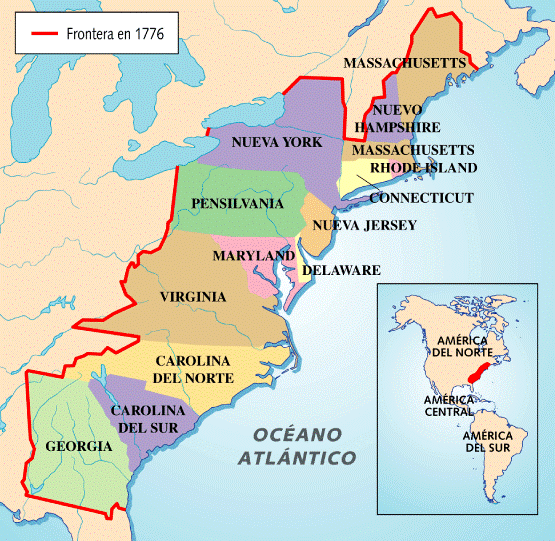

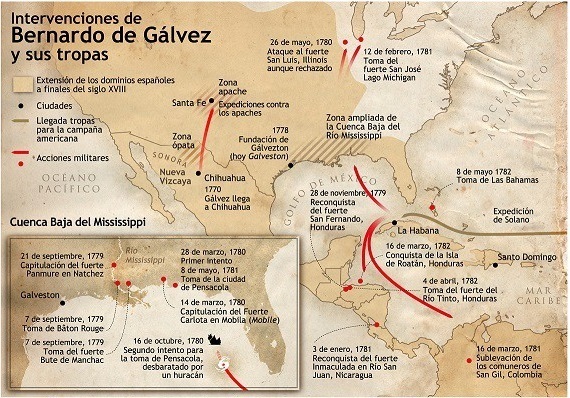

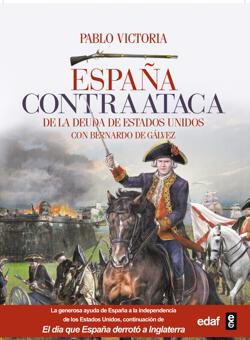

La acción del gobernador malagueño y sus fieros soldados llevó a ladestrucción de no pocas fortalezas británicas situadas en torno al río

Missisipi. Al mismo tiempo, se hizo con el control de la importante plaza deMobile -a pesar de haber perdido varios hombres y navíos en

La acción del gobernador malagueño y sus fieros soldados llevó a ladestrucción de no pocas fortalezas británicas situadas en torno al río

Missisipi. Al mismo tiempo, se hizo con el control de la importante plaza deMobile -a pesar de haber perdido varios hombres y navíos en