Born a slave late enough in the course of the

antebellum era not to have to endure the scourge of that cursed

institution for life, Anna Julia Cooper believed that intelligent

women's voices brought balance to the struggle for human rights. She

manifested her superior intellect and persuasive oratory ability

primarily as a Washington D.C. educator, but also worked as a teacher

of mathematics, Greek, and Latin at St. Augustine's Normal and

Collegiate Institute in Raleigh, North Carolina (1873-81 and 1885-87);

teacher of ancient and modern languages, literature, mathematics, and

language department head at Wilberforce University in Xenia, Ohio

(1884-85); and teacher of languages on a college level at Lincoln

Institute in Jefferson City, Missouri (1906-10). As an intellectual,

embryonic feminist/womanist theorist and critic, master teacher, and

philosopher, Cooper displayed consistent erudition and exactness. A

Christian woman of high standards, principles, and moral caliber she

seemed to have lived an errorless existence to the point of being

faultless. Cooper's experiences with racism and sexism were most

likely the impetus that stimulated her to challenge prevailing

patriarchal exclusionary practices. She referenced herself as

“Black” at a time when the nineteenth century coinage for African

Americans was “Negro.”

Racism scarred her as an activist in the North

Carolina Teachers Association when she sought salaries for African

American teachers that were equitable to White teachers' salaries

(1886). Further humiliation of a racist nature occurred in 1892 when

railroad personnel ejected her from the waiting room—first class

ticket in hand—in her hometown of Raleigh, North Carolina because of

color discrimination. Sexism bruised her emotionally as a student at

St. Augustine's Normal and Collegiate Institute (1868-73) when she

protested against the differences between boys' and girls' curricula

and the availability of financial assistance for boys but no matching

funds for girls. School officials later admitted her to the Greek

course initially set up for men. Cooper came face-to-face with sexism

again when she entered Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio in 1881 and

discovered that it had a “Ladies” course, an experiment in

educational access that was inferior to the classical course offered

to men. This practice prevailed although Oberlin faculty had a

reputation of being progressive thinkers, and the college was among

the first to open its doors to students of African heritage.

Nevertheless, university officials returned to the dominant thought of

the nation and upheld the norm of racism, segregating dormitories and

making admission of qualified African Americans difficult, if not

impossible. Ironically, at St. Augustine's Normal and Collegiate

Institute Cooper met and married in 1877 the ministerial

candidate—the second African American in North Carolina in 1879 to

be ordained an Episcopal priest— and professor of Greek, George A.

Christopher Cooper of Nassau, Bahamas, British West Indies, only to

lose him to death September 27, 1879. As a widow Cooper was free to

pursue greater educational opportunities.

After entering St. Augustine's Normal and Collegiate

Institute for emancipated African Americans on scholarship in 1868 as

a nine and a half-year-old precocious youngster, Cooper began in 1869

at age eleven to tutor students older than she, evidence of her

advanced academic ability at a tender age and indication of her future

career path. The school's mission was to train future teachers, and

Cooper's destiny was established. As a twenty-three-year-old Oberlin

College entering freshman in 1881 Cooper selected the more prestigious

classical “Gentleman's Course” of study, earning the AB (1884) and

MA (1887) degrees, along with Mary Church Terrell (1863-1954) and Ida

Gibbs Hunt (1862-1957). Oberlin administrators awarded Cooper the

advanced degree based on her college teaching ability. In her career

as a public school educator at the Washington High School in

Washington D.C. Cooper worked first as a mathematics and science

teacher (1887-1902). She then became a Latin teacher and principal of

the distinguished M Street High School, established in 1891, formerly

the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth. Cooper was the second

woman—the first was Emma J. Hutchins—to serve the institution in

this male-dominated capacity—(1902-06). This institution produced

some of the greatest African American professionals of the late

nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Not far from the old M Street High

School location a larger edifice on a new site to serve a greater

population was completed in 1916 (razed in 1976) and renamed Paul

Laurence Dunbar High School. Cooper was an influential force in the

new name of the M Street High School, as well as lyrical composer of

its Alma Mater (1924), which was set to music by Mary L. Europe, her

former student turned colleague.

However, for Cooper the leadership role of principal

became daunt, overshadowed with disdain by some school officials who

abhorred Cooper's managerial style and record of success rather than

the lack of it. Cooper's White supervisor Perry Hughes urged the

school board to force Cooper's resignation and relieve her of her

position following controversial statements printed in the Washington

Post regarding pending restrictions of classical education to

African Americans, a controversy precipitated by a speech delivered at

the school in 1902 by W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963), author of The

Souls of Black Folk (1903) and the twentieth century's most

esteemed African American intellectual and Atlanta University

professor at the time. Hughes objected to Cooper's college preparatory

course design and her determination to make African American students

competitive with Whites.

A classical course of study gave African American

students an advantage to compete for scholarships to prestigious

universities, including Ivy League institutions, but business courses

were offered at the school as well. Moreover, the academic

performances of M Street High School students created a perplexing

problem for many Whites regarding stereotypical notions of

intellectual inferiority among African Americans. The students proved

the stereotype untrue. Hughes was a proponent of Up from Slavery

(1901) author Booker T. Washington's (1856-1915) educational

philosophy to instruct African Americans in the industrial and

vocational trades. Also damaging to Cooper were the claims of student

misconduct at the school, teacher immorality, and the rumors of an

alleged affair with John Love, a colleague several years her junior

who was also relieved of duties as a teacher at the school. More

accurately, racist school board members frowned on women in leadership

roles and married or widowed professional women guiding youth. An

independent thinker and the fortitude to stay the course, Cooper could

not be swayed from her vision of superior education and the mastery of

high academic content for African American youths. She was also a

proponent of higher education for women and compassionate about

educational opportunities for the children of former slaves. Although

she had the support of the faculty, students, and citizenry, she paid

the highest penalty of dismissal. Upon the appointment of a new

superintendent Cooper returned to the M Street High School/Dunbar High

School in 1910 as a Latin teacher and retired from the institution in

1930.

In the summer of 1911 Cooper enrolled at à la

Guilde Internationale à Paris, returning in the summers of 1912 and

1913 to study the history of French civilization with Professor Paul

Privat Deschanel, French literature, and linguistics, earning a

Certificate of Honorable Mention. Columbia University in New York City

accepted her as a doctoral candidate July 3, 1914 based on her

academic achievement in France and certified her language proficiency

in French, Greek, and Latin. She began a doctoral thesis in French but

was unable to meet Columbia's mandatory one-year residency rule. In

the summer of 1924, the decade of the 1920s considered the height of

the Harlem Renaissance, Cooper transferred her Columbia equivalency

status credits to Université Paris—Sorbonne where she completed her

doctoral requirements at the age of sixty-five, becoming the fourth

African American woman affiliated with the M Street High School/Dunbar

High School to earn a PhD. The others were Georgiana Rose Simpson, Eva

Beatrice Dykes, and Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander. She also was the

fourth African American woman in the United States to earn a PhD.

Cooper was also the first woman and the first African American woman

resident of Washington D.C. to earn a PhD from the Sorbonne, as well

as the first African American woman born a slave to do a doctoral

defense at the Sorbonne.

In keeping with her standard as the consummate

educator, Cooper advocated extension education for employed adults.

She devoted long uncompensated hours to Frelinghuysen University in

Washington D.C. , founded in 1906 by Dr. Jesse Lawson and his wife

Rosetta E. Lawson, serving as one of its teachers and its second

president (1930-41), as well as relocating the school to her home at

201 T Street, NW in the LeDroit Park community to hold classes when

university authorities faced eviction from the main campus building.

Today Cooper's home is part of the African American Heritage Trail and

the Historical Society of Washington D.C. Struggling economically

through the depression and losing its charter in 1937, the financially

strapped establishment became Frelinghuysen Group of Schools for

Employed Colored Persons in 1940, and Cooper served as registrar

(1940-50), continuing her loyal commitment to the edification of

African Americans even as an elderly educator.

Cooper was a tireless community, political, and

social activist. She was one of three African American teachers

(Parker Bailey and Ella D. Barrier) who participated in a Toronto,

Canada cultural exchange program arranged by the Bethel Literary and

Historical Association (1890s). She also addressed the Convocation of

Black Episcopal Ministers in Washington D.C. (1886) and the

Convocation of Clergy of the Protestant Episcopal Church the same year

on the topic of “Womanhood A Vital Element in the Regeneration and

Progress of a Race”; read her essay “The Higher Education of

Women” at the American Conference of Educators in Washington D.C.

(1890); shared the podium with Booker T. Washington at the Hampton

Conference (1892)in Virginia; was one of three women (Fannie Jackson

Coppin and Fannie Barrier Williams) to explicate poignantly at the

Women's Congress in Chicago which coincided with the World's Columbian

Exposition (1893); was one of three women (Helen A. Cook and Josephine

St. Pierre Ruffin) to address the National Conference of Colored Women

(1895) in Boston, spoke at the National Federation of Afro-American

Women (1896) in Washington D.C. ; was one of two women (Anna Jones) to

represent African American views at the Pan-African Conference in

London (1900); and lectured at the Biennial Session of Friends'

General Conference in Asbury Park, New Jersey (1902).

Moreover, she helped to organize the Colored Woman's

League (1892), founded the Colored Women's Young Women's Christian

Association—Phyllis Wheatley YWCA—(1904) and its chapter of Camp

Fire Girls (1912), and was one of the founders of the social services

organization The Colored Settlement House (1905). She was women's

editor of The Southland magazine (1890), possibly the first

African American magazine in the United States devoted to keeping

readers informed of issues and progress. Impressively, Cooper was the

lone female invited to membership in the elite American Negro Academy,

an African American intelligentsia organization founded by Rev.

Alexander Crummell March 5, 1897. Officials of the organization

included W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963), president and Rev. Francis J.

Grimké, treasurer. Members included the father of Black History

Week/Month Carter G. Woodson and co-founder of the Negro Society for

Historical Research Arthur A. Schomburg (1874-1938) whose collection

of Africana documents would culminate into the New York Public

Library's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Cooper was born Annie Julia—named for the woman

for whom her mother was leased out to work as a nanny—August 10th to

Hannah Stanley Haywood (1817-99), a slave woman with minimal reading

and writing skills. She paid homage to her mother by naming a division

of Frelinghuysen University the Hannah Stanley Opportunity School,

designed for the purpose of educating adults with limited opportunity

for advanced schooling. Her father was George Washington Haywood,

brother of her mother's owner Dr. Fabius J. Haywood, Sr. , a wealthy

entrepreneur who amassed a fortune through family enterprises

involving the acquisition of land, assumption of loans and promissory

notes, leases and rentals, merchandising, partnerships,

pharmaceuticals, and slaves. Her siblings were musician and bandleader

Rufus Haywood (1836?-92) and Spanish-American War veteran Andrew

Jackson Haywood (1848-1918). Andrew married Jane Henderson McCraken in

1867. They adopted a son, John R. Haywood who married Margaret Hinton

whose untimely death led Cooper to assume guardianship of their

children—Regia, John, Andrew, Marion, and Annie—at a time when she

pursued higher education and assumed a mortgage to house her

burgeoning family (1915). Their ages ranged from six months to twelve

years. The infant Annie, her namesake and future heir, died from

pneumonia at the youthful age of twenty-four, a devastating blow to

Cooper and her hope of a successor. She was also foster mother to Lula

Love Lawson, an 1890 graduate of the M Street High School, and her

brother John, orphaned by the death of their parents. Cooper's

maternal grandfather, the slave Jacob Stanley, was skilled in the

building trades and was instrumental in the planning and construction

of the North Carolina State Capitol.

In 1925 under the guidance of Professor Alexander

(French history and language) of Columbia University Cooper published

her Columbia University thesis, Le Pélerinage de Charlemagne:

Voyage à Jérusalem et à Constantinople (The Pilgrimmage of

Charlemagne: Journey to Jerusalem and to Constantinople), a

translation into modern French of an eleventh-century French epic that

became a standard classroom text. Her Université Paris—Sorbonne

dissertation, “L' attitude de la France à l'égard de l'esclavage

pendant la Révolution” (The Attitude of France towards Slavery

during the Revolution), also written completely in French, was the

culmination of her formal education leading to the doctorate. Cooper's

French instructors at the Sorbonne were sociology professor Célestin

Bouglé, political history professor Charles Seignobos, and literature

and American civilization professor Charles Cestre. The French Embassy

in the United States was instrumental in Cooper's receiving her

diploma. District Commissioner William Tindall, the French ambassador

to the United States, the American ambassador to France Emile

Daeschner, and a representative from Columbia University presented the

PhD diploma to her at Howard University's Rankin Chapel on December

29, 1925 in a ceremony hosted by Xi Omega chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha

sorority and Dr. Alain Locke (1886-1954), Howard University philosophy

professor, first African American Rhodes scholar, articulator of the

New Negro Movement which became the Harlem Renaissance, and speaker

for the occasion.

Cooper's dissertation is an inquiry into French

president Raymond Poincare's (1860-1934) attitude regarding racial

equality. She also examines the 1896 French-Japanese Treaty and French

naturalization laws as they pertain to Japanese, Hindu, and Black

people. The Society of Black Friends is explored. Cooper also analyzes

a speech given by Alphonse de Lamartine (1790-1869), French poet and

politician, and a speech delivered during the French revolution at the

National Assembly. Cooper discusses, too, a March 1842 banquet

regarding slavery abolishment.

Over the span of a few years the flame of Cooper's

early feminist/womanist thinking exploded into a full fire. The result

is the seminal publication A Voice from the South, By a Black

Woman of the South (1892), a compilation of various speeches and

lectures that she delivered on public platforms. The book's recurrent

themes are education and feminism. Cooper espouses a

non-confrontational approach to issues of race, class, and gender and

the domination and oppression of women by both Black and White men and

encourages women to expose and attack injustice wherever it exists.

She gears the essays to a learned audience, not to the emancipated

slaves who were mostly illiterate, though she champions their cause.

The book is for the teachers of this deprived population who have the

responsibility and the authority to introduce new ideas and challenge

minds, especially women in the profession, all women in general and

African American women in particular. Her genre is the formal essay.

She uses it to explain her philosophical stance, combining facts,

theory, and sincere purpose. Her essays are classical in form,

structure, and style, but they are also autobiographical and

introspective narrative, incorporating her perspectives of life's

experiences. She uses the language of Christian doctrine to examine,

support, and specify her ideas, quoting relative scriptural texts that

illustrate her views. She considers scriptural references manna for

living the right kind of life. She also uses poetry within her essays

to emphasize important points. Her essays are discussions of political

topics to inspire change by appealing to the consciences of reasonable

readers who may be empowered to act. The book is indicative of the

cultural value of the essay as a political tool for nineteenth-century

African American women.

Cooper feels that the “woman's era” (1890s) when

women activate their voices in the National Association of Colored

Women's Clubs and woman suffrage is an excellent time to “examine

the feminine half of the world's truth.” Her book contains two

sections of four essays each. The first section, “Soprano Obligato,”

focuses on women's issues, nineteenth century women facing the new era

of the twentieth century in which they will have vital impact. The

next section, “Tutti Ad Libitum,” analyzes the race problem and

its negative effects in American society. Both sections address the

human condition and how best to improve the status of those relegated

to the lowly places in life. In Cooper's opinion America failed to

provide mechanisms of uplift to all its citizens, for any society that

dooms any of its members to a permanent low caste will never achieve

the fullness of its possibilities. The period in which Cooper writes,

the 1890s, is an era in which women, African American and White, tear

down barriers that prohibited them from becoming productive and

meaningful contributors to society. However, society at this time is

more receptive to White women although mass protests are the channels

used to gain them this tolerance. The 1890s also mark a backlash in

African American progress, and it is a climate that tolerates an

increase in lynching. Cooper feels that the time is suitable for the

“voiceless Black Woman of America” to explain in detail America's

problems, and the relevance of the time in which African Americans are

twenty-seven years out of chattel slavery.

The first essay in the book, “Womanhood a Vital

Element in the Regeneration and Progress of a Race,” identifies two

sources responsible for perpetuating images of women, the Feudal

System and Christianity. The former initiated honor and respect and

the latter reverence, but, according to Cooper, both are unrealized.

Cooper believes that women's past is not their doing, but the future

is theirs to control if they reject ignorance and accept higher goals,

i.e. , acquiring higher education. She warns that intellectual

weaknesses in the nineteenth century are attributable to patriarchs of

the institution of slavery but a century later will be used as proof

of innate inferiority. She recapitulates some of the myths surrounding

women and intelligence in “The Higher Education of Women,” which

includes a section that addresses “The Higher Education of Colored

Women.” She maintains that higher education does not reduce women's

eligibility for wifehood or motherhood or nullify their domestic

ability; men and women can approach matrimony as equals educationally

and economically, for their higher knowledge qualifies them even more

in the managing of households and in the training of children. For

African American women she espouses intellectualism with the balance

of Christian virtues, indicating that a strong moral fiber must

accompany in-depth knowledge of arts, sciences, business, and social

work. The essay “Woman Versus the Indian” highlights dedication to

the survival and wholeness of all people, but its title is misleading.

She posits a theory that all avenues of social life are under the

auspices of women, e.g. , a national standard of courtesy—“like

mistress, like nation.” She believes that women are the moral

conscience of the nation, practitioners of good manners and the Golden

Rule, which if women apply universally would shake the foundations of

racism and the stronghold that men have on society. “The Status of

Woman in America” pays homage to women's strength and to the

celebration held in Chicago of the “fourth centenary” of the

continent's discovery. Since the nation's founding Cooper believes

that women have been in training to assume leadership positions, to

effect change in the twentieth century, and to recognize the

contributions of African American women to America.

“Has America a Race Problem; If So, How Can It

Best Be Solved?” is the lead essay of the second section. Cooper

elaborates on issues of race and class and identifies two kinds of

peace, the kind that comes from suppression and the kind that evolves

from adjustment. Her preference is the latter, that compromise,

reciprocity, and tolerance are the only survival tools of the nation.

Cooper assumes the role of literary and social critic in “One Phase

of American Literature.” Her commentary centers on economic

self-determination, reparations for African Americans, and love and

appreciation for the folk, the “silent factor,” the producers of

true American literature (folklore and folk songs). “What Are We

Worth?” examines the economic ramifications that form African

American civilization since Emancipation. She writes that the world

benefits from inventions by African Americans but is unaware of the

role played by them in making lives easier. She pays tribute to

individuals whose contributions and inventions improved the lot of

humanity, calling this litany of names a “noble army” and “roll

of honor.” In “The Gain from a Belief” Cooper has a spiritual

focus and explores absolute and eternal truth, knowledge, and virtue,

necessary in the building of faith. Her view is that people need

something in which to believe, and “faith means treating the

truth as true.” She believes that faith benefits the newly

freed African American nation to persevere and drum up the gumption to

get to the next century and beyond.

Cooper delivered many of her lectures in African

American churches and perhaps for that reason the essays have a

Christian emphasis. She also introduced her ideas before learned

societies and community organizations. She uses the lecture circuit as

a political platform to postulate her theories of educational access

and social action and responsibility. Cooper's critical expressions

are idealistic, philosophical, and practical. Her theories are not

just ideas of the imagination but something more fundamental, the

incorporation of consciousness into what might be perceived as

thinking in the abstract. She considers each and every thought and

concludes that cognizance and consciousness are inseparable. The

experiences of the new African American nation do not occur

independently of what goes on in the mind. She believes if individuals

can think things, then people can achieve things. Her theories differ

from traditional Eurocentric theories because they are not merely

academic exercises to be discussed in academic circles. They are

aesthetic and practical; they are for the masses, not just the

cultural elite, although she stresses that an educated African

American class with the capacity to lead must implement the theories.

Cooper basically states tactics of survival. She encourages people to

do as nature does, take examples from nature's book of fair play. Hers

are theories in conflict resolution, a prototype which stresses never

to give up the struggle against misconceptions regarding race, class,

gender, politics, education, and economics. She remained an academic

motivator until her death from cardiac arrest at the age of 105,

concerned with the educational development of women and the

underrepresented. Cooper felt that her work in the progression of

higher education of women was unfinished. She ran out of time, but she

left a powerful legacy.

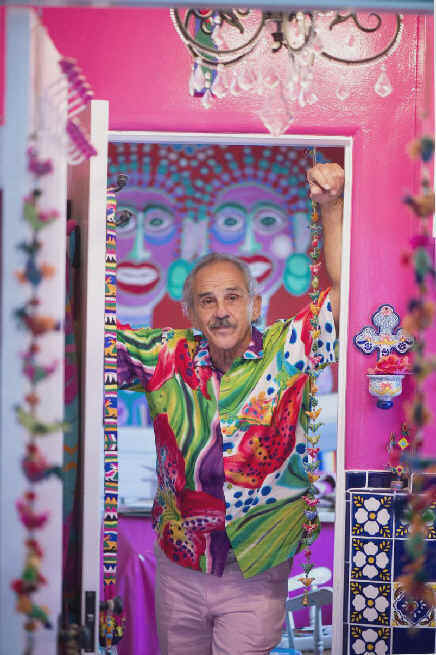

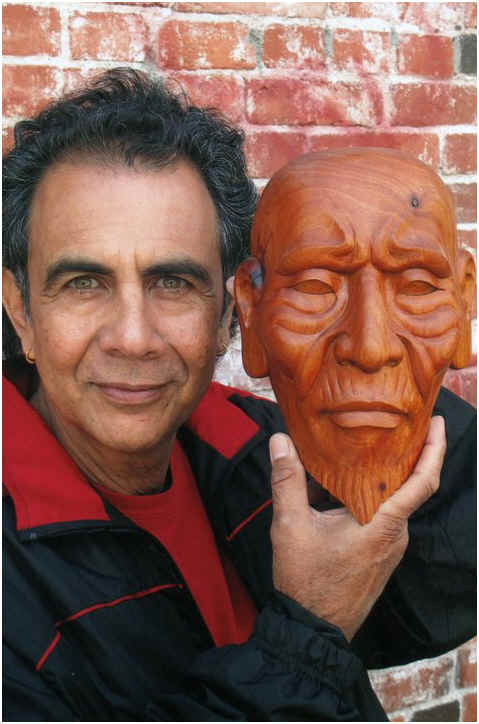

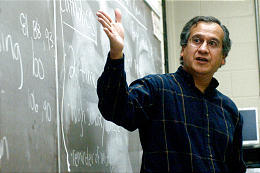

Fast forward. Serna is 70. And somebody, director Dave Boyle, not only hired him for the indie thriller “Man From Reno” but the part – Serna’s first leading role – was written specifically for him.

Fast forward. Serna is 70. And somebody, director Dave Boyle, not only hired him for the indie thriller “Man From Reno” but the part – Serna’s first leading role – was written specifically for him.

.jpg/220px-Eduardo_Galeano_ltk_(cropped).jpg)

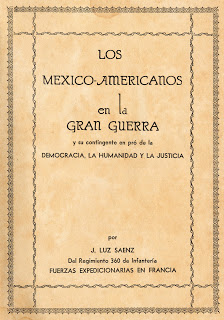

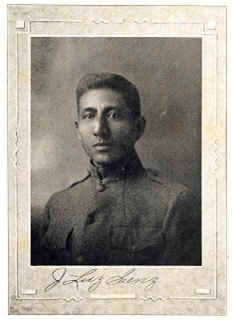

Military service also made it possible to serve the young in a more general way: “My country’s call took me from where I was, teaching the children of my people, and placed me where I could defend their honor, their racial pride, where I could assure them a happier future.”

His plans were to return to Texas and to point to the military contribution of Mexicans to justify a civil rights agenda. Luz thus called on Mexicans to consciously link the wartime language of democracy and the Mexican civil rights cause.

Luz also defined the Allied cause and the fight against discrimination in Texas as one war. Although the conflict was occurring in different places and involved different issues, the fighting was joined by a general concern for the rights of the dispossessed, both in France and in Texas.

Military service also made it possible to serve the young in a more general way: “My country’s call took me from where I was, teaching the children of my people, and placed me where I could defend their honor, their racial pride, where I could assure them a happier future.”

His plans were to return to Texas and to point to the military contribution of Mexicans to justify a civil rights agenda. Luz thus called on Mexicans to consciously link the wartime language of democracy and the Mexican civil rights cause.

Luz also defined the Allied cause and the fight against discrimination in Texas as one war. Although the conflict was occurring in different places and involved different issues, the fighting was joined by a general concern for the rights of the dispossessed, both in France and in Texas. His earliest venture into public life allowed him to embrace his indigenous identity and to launch a career as a teacher and leader in the Mexican community of South Texas. At about the same time as his graduation, Luz and a small group of friends established a literary club and organized a formal celebration commemorating the birth and life of Benito Juarez, a member of an indigenous community who became one of Mexico’s major historical figures.

His earliest venture into public life allowed him to embrace his indigenous identity and to launch a career as a teacher and leader in the Mexican community of South Texas. At about the same time as his graduation, Luz and a small group of friends established a literary club and organized a formal celebration commemorating the birth and life of Benito Juarez, a member of an indigenous community who became one of Mexico’s major historical figures.

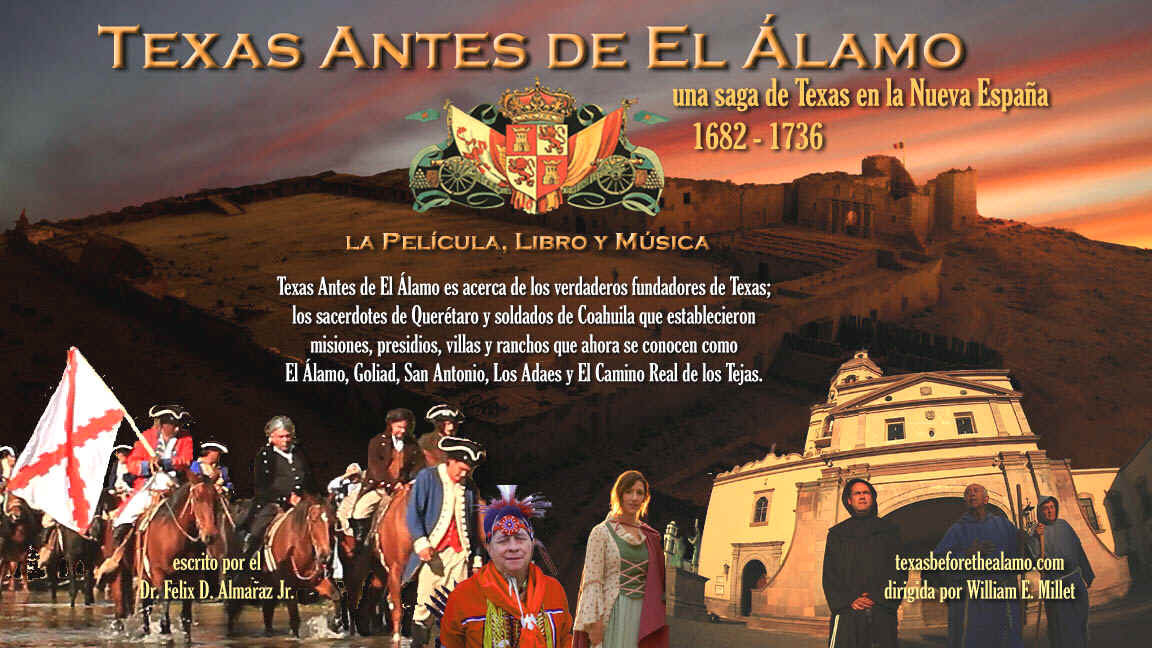

The Battle of San Diego Bay, however, is a reminder of Spain’s early exploration of the Pacific, which was referred to as “Lagos Espanola,” or Spanish Lake, said Angeles Leira of the House of Spain, a cultural history organization.

The Battle of San Diego Bay, however, is a reminder of Spain’s early exploration of the Pacific, which was referred to as “Lagos Espanola,” or Spanish Lake, said Angeles Leira of the House of Spain, a cultural history organization.

“It was an evolution—I wasn’t born a muralist right away!” laughs Levi Ponce. “My dad’s a sign painter for a living; he’s been doing it for 50 years. Growing up, I would go to work with him, ever since I was potty-trained, actually. My Mom said, ‘I got him Monday through Friday—you got him on the weekends!’ He would have me do basic stuff like ‘Paint this post white.’”

“It was an evolution—I wasn’t born a muralist right away!” laughs Levi Ponce. “My dad’s a sign painter for a living; he’s been doing it for 50 years. Growing up, I would go to work with him, ever since I was potty-trained, actually. My Mom said, ‘I got him Monday through Friday—you got him on the weekends!’ He would have me do basic stuff like ‘Paint this post white.’” “I

thought, ‘What better way to advertise yourself than to paint a big

mural?’” Applying his bold style on a large scale, he painted actor

Danny Trejo in 2011. “From day one, the experience was unforgettable.

It immediately changed from potential profit to ‘I need to do this

again!’”

“I

thought, ‘What better way to advertise yourself than to paint a big

mural?’” Applying his bold style on a large scale, he painted actor

Danny Trejo in 2011. “From day one, the experience was unforgettable.

It immediately changed from potential profit to ‘I need to do this

again!’”

American

Sabor: Latinos in U.S. Popular Music will celebrated their final exhibition at Arizona Latino Arts and Culture Center in the heart of Downtown Phoenix. American Sabor has been traveling cross-country for ten years and has chosen to celebrate its incredible journey with people of Phoenix one last time.

American

Sabor: Latinos in U.S. Popular Music will celebrated their final exhibition at Arizona Latino Arts and Culture Center in the heart of Downtown Phoenix. American Sabor has been traveling cross-country for ten years and has chosen to celebrate its incredible journey with people of Phoenix one last time.

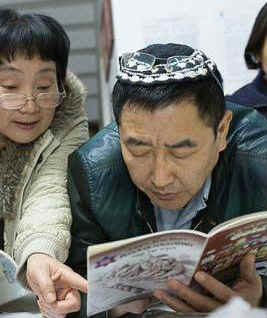

Every couple of weeks, the Salcedo family travels more than an hour from Yuma, Ariz., to dine at Fortune Garden.

Photo Courtesy of Vickie Ly/KQED.

Every couple of weeks, the Salcedo family travels more than an hour from Yuma, Ariz., to dine at Fortune Garden.

Photo Courtesy of Vickie Ly/KQED.  Fried yellow chilis in the Fortune Garden kitchen. This dish showed up on almost every table at the Chinese restaurants we visited on both sides of the U.S. border with Mexico. Their sauce has kind of a margarita flavor: lemon with lots of salt.

Fried yellow chilis in the Fortune Garden kitchen. This dish showed up on almost every table at the Chinese restaurants we visited on both sides of the U.S. border with Mexico. Their sauce has kind of a margarita flavor: lemon with lots of salt.

Mimi:

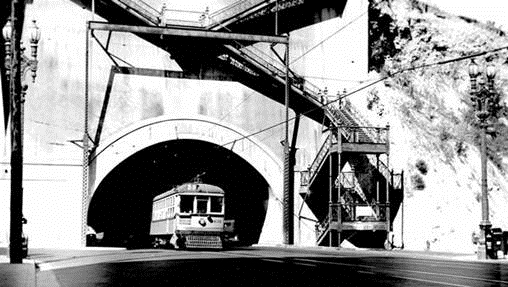

Following is an article from our news from years ago. I am submitting this fantastic bit of Victoria's railroad history for two main reasons: my grandfather, Julio Lopez, worked for Southern Pacific Railroad for over 50 years! The photo of the railroad crossing

(above) could have been taken from my front door, as we lived next to the railroad tracks most of my growing-up life, and the Depot was just a skip-and-a-hop away. It was the neighborhood called Dutch Lane. The Caboose, in particular, is significant because my grandfather would always stand in the back and "throw" us fruit, like bananas, when it passed by. The whistles and very loud horn-blowing was our time-keeper. We knew what time it was when the railroad came by. The Railroad depot burned down, and now it's a vacant lot that I pass by the area every single day. Trains do go by, but not like in the "olden days."

Mimi:

Following is an article from our news from years ago. I am submitting this fantastic bit of Victoria's railroad history for two main reasons: my grandfather, Julio Lopez, worked for Southern Pacific Railroad for over 50 years! The photo of the railroad crossing

(above) could have been taken from my front door, as we lived next to the railroad tracks most of my growing-up life, and the Depot was just a skip-and-a-hop away. It was the neighborhood called Dutch Lane. The Caboose, in particular, is significant because my grandfather would always stand in the back and "throw" us fruit, like bananas, when it passed by. The whistles and very loud horn-blowing was our time-keeper. We knew what time it was when the railroad came by. The Railroad depot burned down, and now it's a vacant lot that I pass by the area every single day. Trains do go by, but not like in the "olden days."

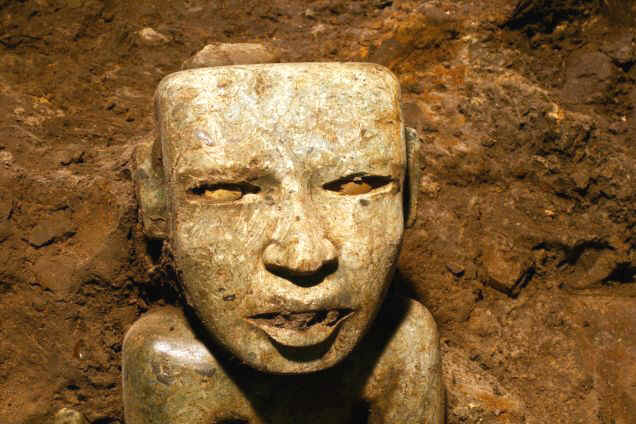

Although other archeologists have reported evidence for such early colonization of the Americas, Richard MacNeish of the Andover Foundation for Archaeological Research said the new site--a cave--provides the most convincing evidence yet.

Although other archeologists have reported evidence for such early colonization of the Americas, Richard MacNeish of the Andover Foundation for Archaeological Research said the new site--a cave--provides the most convincing evidence yet.

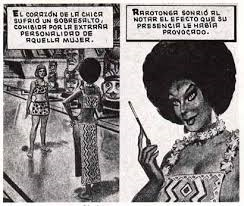

She

was a huge hit. Circulation topped a million making Rarotonga

"one of the firm's greatest successes." A company report

issued four years ago noted the series "had an impact studied by

psychologists and sociologists. It involved a hyped-up, imaginary

character that cast such a spell on the public, especially young

people, that many adopted her personality. Her hairdo became famous al

over Mexico."

She

was a huge hit. Circulation topped a million making Rarotonga

"one of the firm's greatest successes." A company report

issued four years ago noted the series "had an impact studied by

psychologists and sociologists. It involved a hyped-up, imaginary

character that cast such a spell on the public, especially young

people, that many adopted her personality. Her hairdo became famous al

over Mexico."